Abstract

B-cell prolymphocytic leukaemia (BPLL) is a haematological malignancy defined as lymphocytosis and splenomegaly with >55% circulating cells being clonal prolymphocytes of B-cell origin. The evolution of this disease is more aggressive than chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. We reported a case of a 62-year-old man with BPLL who, on treatment, attained cytological, immunophenotypic and complete cytogenetic remission. He subsequently developed an asymmetric sensorimotor neurological disorder, suggestive of lymphomatous infiltration (neurolymphocytosis). Repetition of the MRI and the electromyography was essential for diagnosis. Progressive mononeuritis multiplex in B-cell leukaemias/lymphomas is rare and may be the only presenting symptom of relapsed or progressive disease. Repeat imaging studies based on judicious evaluation of the clinical scenario for exclusion of other causes of neurological symptoms is necessary. This can be challenging in patients with long-standing malignancies who have received multiple courses of chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy.

Background

B-cell prolymphocytic leukaemia (BPLL) is an extremely rare disease, comprising approximately 1% of all lymphocytic leukemias. Most patients are over 60 years of age and present with B-symptoms, massive splenomegaly, marrow infiltration with minimal or no lymphadenopathy. Elevated lymphocyte counts (often >100×109/L) are common, with prolymphocytes exceeding 55% of circulating lymphoid cells. Disease evolution is more aggressive than chronic lymphocytic leukaemia.1

We reported a case of a 62-year-old man treated for BPLL who subsequently developed an asymmetric sensorimotor neurological disorder (mononeuritis multiplex, MNM).

Case presentation

A 62-year-old man was first seen in June 2004 for splenic infarction, splenomegaly and hyperlymphocytosis with a total lymphocyte count of 181×109/L, composed of 90% B-cell prolymphocytes. Haemoglobin level and platelet count were, respectively, 122 g/L and 167×109/L.

BPLL was diagnosed through the examination of morphology, immunophenotype (CD5+, CD19+, CD20+, CD38+, CD79b+, CD22+, high-intensity lambda light chain immunoglobulin, CD10−, CD23−, cyclin D1−) and karyotyping (t(8;14) by conventional cytogenetic analysis and fluorescence in situ hybridisation.

The patient was initially treated with fludarabine (6 regimens), then with R-FND (6 regimens of rituximab–fludarabine–mitoxantrone–dexamethasone) for his first cytological and karyotypic relapse (October 2008). He was in complete remission twice between 2004 and 2008, and between 2009 and 2010.

In July 2010, he relapsed only with left cervical adenopathy showing the same initial (in 2004 and 2008) karyotipic features. The patient received R-VACP (2 regimens of vincristine–doxorubicine–cyclophosphamide–prednisone), then R-ESAP (3 regimens of etoposide–cisplatine–cytarabine–prednisone) due to a partial response to R-VACP. Examination of the patient showed no clinical lymph nodes but 18F-fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose (FDG) positron emission tomography- CT revealed persistent non-fixing nodes in IIA area. Complete response was considered and the treatment was consolidated by left cervical lymphatic irradiation. It was planned to irradiate right cervical lymph nodes (II A, II B, III, IV and V areas), 2 Gy, five times per week, during 4 weeks.

After a total radiation dose of 20 Gy, in January 2011, the patient was diagnosed with neuralgia of the left upper limb and C8-D1 sensory and motor disorders. Unstable walking was reported because of cerebellar ataxia.

Investigations

Electromyography (EMG) of his four extremities showed MNM with reduced motor and sensory potential amplitudes and evidence of acute and chronic denervation within the boundary of organ involvement. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis was normal, without onconeural antibodies (antibodies against Hu, Yo, Ri, CV2, Ma, VGKC testing in blood and CSF). No sign of infiltration or compression was seen on imaging (cervicothoracic CT, medullar MRI. Neuromuscular biopsy from anterolateral compartment of left leg did not show any evidence of vasculitis, amyloidosis or lymphoma infiltration.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis included neoplastic infiltration or compression, paraneoplastic neurological syndrome, toxic processes of chemotherapy or radiotherapy, autoimmune (cryoglobulinemia, amyloid) or infectious (Lyme neuroborreliosis) mechanisms.

Treatment

During the following month, his symptoms progressively deteriorated until he had complete lower limbs and left upper limb paralysis, amyotrophy and ataxia. Neuralgia was reported to be severe despite administration of morphine and antidepressant agents. High-dose intravenous methylprednisolone pulse therapy and polyvalent immunoglobulins eventually stopped the progression of the neuropathy.

Outcome and follow-up

EMG of his four extremities was repeated 1 month later (February 2011) and revealed complete neuropathy of the left brachial plexus and both common fibular and tibial nerves. Fibrillation potentials, denervation potentials and absence of voluntary motor activity suggested acute diffuse axonal injury.

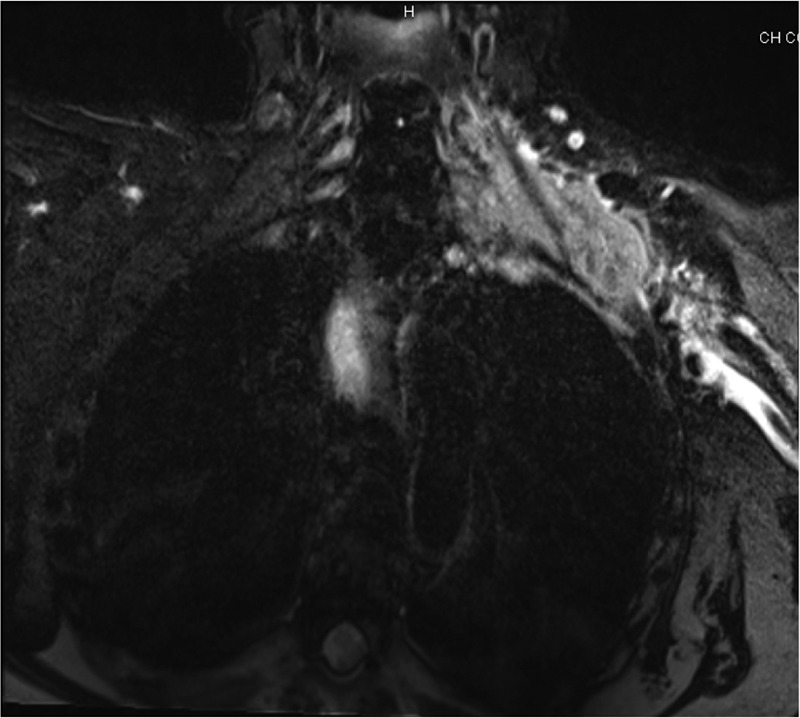

MRI showed an invasive mass, involving the brachial plexus to the lung apex, with infiltration of the left neurovascular plexus (figure 1). A neuromuscular biopsy and PET-CT were not reiterated in time to confirm diagnosis of secondary neurolymphomatosis (NL). Rituximab–cytarabine–methotrexate was chosen for their good neural (blood–brain and blood–nerve barrier) penetration; one cycle was given but without tumour response. Bilateral upper extremities paralysis and tumoural mass infiltration of the airways were reported. The patient died 2.5 months (March 2011) after the onset of neurological symptoms. No autopsy was performed.

Figure 1.

Plexus brachial MRI, T2: hyperintensity of left cervical and axillary regions (9×3 cm).

Discussion

The patient had a history of B haematological disease. Neurological disorders appeared while on therapy. MNM aetiology2 was difficult to recognise. Only, iterative MRI and EMG findings led to a probable diagnosis of secondary neurolymphomatosis.3

Lymphomas can cause peripheral neuropathies which occur most frequently through direct infiltration of nerves, paraneoplastic, metabolic, infectious mechanisms or treatment adverse events. One of the most common causes of NL is non-Hodgkin lymphoma B.

NL is defined by Kelly et al4 as clinical neuropathy associated with malignant, lymphomatous infiltration of peripheral nerves. The diagnosis can be carried out through a biopsy or an autopsy when NL is the first manifestation of malignancy (primary NL). However, when the symptoms occur because of relapse or progression of a previously treated disease (secondary NL), the diagnosis is done through exclusion of other causes of neuropathy, positive images revealing specific neural involvement and evidence for disease progression.3 4 NL patients may present with polyradiculopathies or a cauda equina syndrome, mononeuropathy, asymmetrical regional neuropathies of a limb. Less common presentations of NL are: diffuse, progressive and subacute or chronic peripheral neuropathy similar to Guillain-Barré syndrome or chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy.5 6

MRI or PET-CT7 can reveal focal or diffuse enlargement of nerves, roots with contrast enhancement. These abnormal findings are not specific to NL. Thus, interpretation of imaging studies in the context of clinical manifestations (history of haematological malignancy) is required for NL diagnosis. The most appropriate target for biopsy may be revealed by positive MRI or PET-CT findings. Neuromuscular biopsy8 is required to confirm diagnosis, but can be negative in 50–70% of cases. Neurological injuries are segmental and focal. CSF could be inflammatory or show malignant cells. The typical electrophysiological and pathological findings of nerve infiltration are a mixed axonal and demyelinating process.

To date, there is no gold standard of treatment for NL. The latter is being treated through chemotherapy alone or combined with radiotherapy. Patients receive systemic or intra-CSF chemotherapy. Systemic chemotherapy includes high-dose methotrexate and/or cytarabine, thanks to their good penetration in the blood–brain and blood–nerve barriers.3

Our case put forward the need for identification of other underlying mechanisms of MNM. Initially, the patient suffered from a mild peripheral neuropathy. Toxic origins of neurological symptoms were first explored. He received several chemotherapies. Postchemotherapy symptoms were not consistent with the literature reporting less painful and progressive symptoms with either paraesthesia or dysesthesia.9 Neurological postchemotherapy disorders can occur in 30–40% of cases. Monitoring and dose adjustment are required to prevent a deterioration of patients life quality. Indeed, postchemotherapy symptoms are chronic. In our presented case, it was difficult to reveal any association between chemotherapy molecules and patient's neurological symptoms.

One of the complications of BPLL is plexopathy. Lymphoma induced plexopathy are very painful10 and sometimes associated with Horner syndrome or meningeal involvement. Moreover, radiotherapy11 symptoms start 6 months postradiation and have a higher impact on patients who have been exposed to higher radiation doses: dysesthesias and paraesthesias with a slow progression over months to years to probable muscular weakness and reflex loss. Diagnostic testings such as EMG can be helpful in distinguishing between toxic and lymphatic aetiology of mass lesions when imaging studies are not conclusive. In addition, EMG can reveal myokymic discharges specific to radiation damage to nerves and are not seen in neoplastic or inflammatory plexopathies.4

Finally, paraneoplastic neurological syndrome (PNS) was discussed.12 It occurs in 5% of patients with small cell lung carcinoma and 10% of those with haematological diseases. In 80% of cases, neurological symptoms come before the tumour. Symptoms are varied: peripheral nervous system diseases, Lambert-eaton myasthenic syndrome, cerebellar ataxia, opsoclonus–myoclonus syndrome, behaviour disorder. Damages are combined, with acute or subacute evolution. No onconeural antibodies have been reported in 30% of patients with neurological symptoms12 As a result, the absence of such antibodies cannot rule-out the PNS diagnosis. Whereas, the presence of onconeural antibodies in such patients should be regarded as a marker of cancer.13

The patient had a history of BPLL and was in complete remission when admitted to our medical unit. Given that his condition rapidly deteriorated neurologically, there could be an indication for peripheral nervous system disease aetiology associated with neoplastic and toxic cause. Diagnostic tests may be negative at the beginning of the pathology. The best diagnostic tests to reveal infiltrates are MRI or PET-CT. In this case, the diagnosis for secondary NL was performed through imaging and clinical involvement judgement. NL diagnosis is rare representing only 3% of NHL. BPLL relapses and drug resistance could be explained by c-myc overexpression, caused by t(8;14) translocation.14

Learning points.

- Progressive mononeuritis multiplex in a patient with known B-cell leukaemia or lymphoma

- Is very rare;

- Warrants repeat imaging studies;

- May be the only presenting symptom of relapsed or progressive disease.

Neurolymphomatosis (clinical neuropathy associated with malignant, lymphomatous infiltration of peripheral nerves) may occur in lymphoid malignancies. Diagnosis requires histological demonstration of infiltration.

In the absence of histological evidence, careful exclusion of other causes of neuropathy, positive imaging findings revealing specific neural involvement and evidence for disease progression are necessary to diagnose neurolymphocytosis as the case of neuropathy.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Jean Christophe Ianotto, CHRU Brest, Zarrin Alavi, INSERM CIC 0502 CHRU Brest and Pascaline Rameau, RIMBO Quimper Unit for their precious advice in writing this case report.

Footnotes

Contributors: LLC wrote the paper. ZA, PH and MJR reviewed the paper.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Lyon: IARC, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stojkovic T. Les neuropathies périphériques: orientations et moyens diagnostiques. Rev Médecine Interne 2006;2013:302–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grisariu S, Avni B, Batchelor TT, et al. Neurolymphomatosis: an International Primary CNS Lymphoma Collaborative Group report. Blood 2010;2013:5005–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelly JJ, Karcher DS. Lymphoma and peripheral neuropathy: a clinical review. Muscle Nerve 2005;2013:301–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stern BV, Baehring JM, Kleopa KA, et al. Multifocal motor neuropathy with conduction block associated with metastatic lymphoma of the nervous system. J Neurooncol 2006;2013:81–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fiegl M, Muigg A, Smekal A, et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with infiltration-associated peripheral neuropathy and paraneoplastic myopathy with a prolonged course over seven years. Leuk Lymphoma 2002;2013:1687–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin M, Kilanowska J, Taper J, et al. Neurolymphomatosis–diagnosis and assessment of treatment response by FDG PET-CT. Hematol Oncol 2008;2013:43–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prise en charge des biopsies musculaires et nerveuses Recommandations formalisées d'experts sous l’égide de la Société française de neuropathologie, de la Société française de myologie et de l'Association française contre les myopathies. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2010;2013:477–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez G, Sereno M, Miralles A, et al. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: clinical features, diagnosis, prevention and treatment strategies. Clin Transl Oncol 2010;2013:81–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bai L-Y, Chiu C-F, Liao Y-M, et al. Recurrent lymphoma presenting as brachial plexus neuropathy. J Clin Oncol 2007;2013:726–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gałecki J, Hicer-Grzenkowicz J, Grudzień-Kowalska M, et al. Radiation-induced brachial plexopathy and hypofractionated regimens in adjuvant irradiation of patients with breast cancer–a review. Acta Oncol 2006;2013:280–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pelosof LC, Gerber DE. Paraneoplastic syndromes: an approach to diagnosis and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc 2010;2013:838–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raspotnig M, Vedeler CA, Storstein A. Onconeural antibodies in patients with neurological symptoms: detection and clinical significance. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl 2011;:83–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuriakose P, Perveen N, Maeda K, et al. Translocation (8;14)(q24;q32) as the sole cytogenetic abnormality in B-cell prolymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 2004;2013:156–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]