Abstract

Tuning the photonic band gap (PBG) to the electronic band gap (EBG) of Au/TiO2 catalysts resulted in considerable enhancement of the photocatalytic water splitting to hydrogen under direct sunlight. Au/TiO2 (PBG-357 nm) photocatalyst exhibited superior photocatalytic performance under both UV and sunlight compared to the Au/TiO2 (PBG-585 nm) photocatalyst and both are higher than Au/TiO2 without the 3 dimensionally ordered macro-porous structure materials. The very high photocatalytic activity is attributed to suppression of a fraction of electron-hole recombination route due to the co-incidence of the PBG with the EBG of TiO2 These materials that maintain their activity with very small amount of sacrificial agents (down to 0.5 vol.% of ethanol) are poised to find direct applications because of their high activity, low cost of the process, simplicity and stability.

Hydrogen production from water offers enormous potential benefits for the energy sector, the environment and chemical industry. There are many methods for producing hydrogen from water and these include solar thermal1, combined photo-voltaic/electrolysis2,3 artificial photosynthesis4 and photocatalysis5. Economic feasibility studies6 indicate that at 5% solar photon conversion the price of hydrogen produced from water photo-catalytically would be competitive with conventional non-renewable processes (e.g. methane steam reforming). At present approximately one half of the total amount of hydrogen produced in the World (about 30 million metric tons/year) is used in ammonia synthesis. If hydrogen could be made from water, then ammonia and fertilizers could be made from totally renewable sources (nitrogen and water). Jules Verne's prediction in The Mysterious Island7 that water would be the fuel of the future could be realised.

Since the pioneering work of Fujishima and Honda8 a large number of photo-catalytic materials have been synthesised and studied for water splitting. These include oxide9, nitride10 and sulphide11 materials. While many advances have been achieved in this area, most materials are either unstable under realistic water splitting conditions or require considerable amounts of other components (sacrificial hole or electron scavengers, and/or often unstable catalysts after extended periods of time), offsetting the gained benefits. In this work we present a novel Au/TiO2 photocatalyst system based on a titania inverse opal support that is efficient and stable in producing hydrogen photo-catalytically from water under sunlight at levels high enough to warrant potential industrial application. The system affords very high conversion of both UV and visible light, thus reaching the land mark of ~5% of total solar conversion. The unusually high activity and high stability of these catalysts is due to the fact that they exploit both the inherent electronic properties of Au and TiO2, and the unique photonic band gap properties of TiO2 inverse opals.

A semiconductor photo-catalyst is a material that can be excited upon receiving energy equal to or higher than its band gap. Upon photo-excitation electrons are transferred from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB) resulting in the formation of an electron (in the CB) and a hole (in the VB). In the case of water splitting, electrons in the CB reduce hydrogen ions to H2 and holes in the VB oxidise oxygen ions to O2. One of the main limitations of most photocatalysts is the fast electron-hole recombination; a process that occurs at the nanosecond scale, while the oxidation-reduction reactions are much slower (micro second time scale). Over 90% of photoexcited electron-hole pairs disappear before reaction by radiative and non-radiative decay mechanisms12. Photonic band gap (PBG) materials have the property of forbidding light (photons) from propagating at specific frequencies, referred to as photonic band gaps (PBGs). In 1987 Yablonovitch13 in his seminal work postulated the following: if a 3-D periodic dielectric structure has an electromagnetic band gap (PBG) which overlaps the electronic band gap spontaneous emission can be rigorously forbidden. In this work, we have prepared and tested 2 wt.% Au/TiO2 (anatase) PBG materials that have PBGs coinciding with the electronic band gap of TiO2. We have also extended the work to 0.5 wt.% Au–0.5 wt.% Pd/TiO2 (anatase) PBG and further enhanced the hydrogen production while decreased the amount (and therefore cost) of noble metal. These catalysts were found to be highly active and stable for hydrogen production with direct sunlight (UV light flux of less than 0.5 mW/cm2). Comparing the photon flux in the UV region to the hydrogen production indicates that most of the photons were used to make hydrogen (Supplementary Information 4).

Results

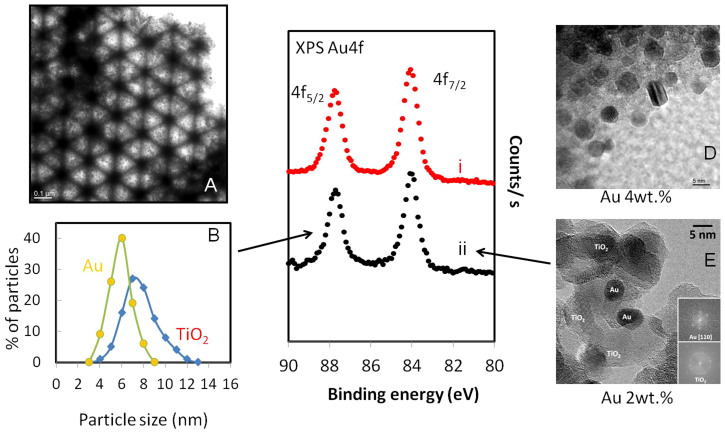

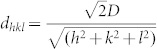

Figure 1 presents transmission electron microscopy (TEM), high resolution TEM (HRTEM) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) of two PBG catalysts (PBG-357 nm and PBG-585 nm). The properties and composition of Au/TiO2 catalysts, where the TiO2 is present in the anatase form, are given. The 3-dimensionally ordered macroporous structure of the PBG materials is clearly seen in Figure 1A, and the anatase TiO2 crystallites (analysed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) – not shown) and Au nanoparticles are seen in figure 1 (D and E). The particle size distribution of both TiO2 and Au are presented in figure 1B; both components (Au and TiO2) are of comparable size with the Au particles smaller. Au4f XPS indicates that Au is present in its metallic form with no apparent charge donation from/to the semiconductor to the metal. The Au/TiO2 (PBG-357 nm) and Au/TiO2 (PBG-585 nm) catalysts prepared in this study are near identical in their chemical compositions as well as their main characteristics (particle sizes, Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area ~60 m2/g, exposed area of Au, support phase and valence band electronic structure14) but differ in their macropore diameter and optical PBG properties. One has a PBG along the [111] direction of 357 nm (in air) whilst the other has its PBG along the [111] direction of 585 nm (in air), as determined from UV-Vis reflectance measurements on TiO2 inverse opal thin films (Supplementary information: S1 and S2). The PBG can be calculated from the distance between two repeating microscopic unit cells (D) using the formula ( ), where m is the diffraction order, θ is the incident angle of light with respect to the surface normal,

), where m is the diffraction order, θ is the incident angle of light with respect to the surface normal,  where D is the macropore diameter and h, k, l are miller indices of the exposed planes, and navg is the average refractive index of the photonic crystal (

where D is the macropore diameter and h, k, l are miller indices of the exposed planes, and navg is the average refractive index of the photonic crystal ( ). The average refractive index of the photonic crystal, and hence the PBG position, λ, depend on the refractive index of the medium filling the macropores in the TiO2 inverse opal.

). The average refractive index of the photonic crystal, and hence the PBG position, λ, depend on the refractive index of the medium filling the macropores in the TiO2 inverse opal.

Figure 1.

(A). TEM of PBG Au/TiO2 photocatalyst. (B). Particle size distribution of Au and TiO2 particles in the PBG Au/TiO2 photocatalyst. (C). XPS Au4f for two PBG Au/TiO2 photo-catalysts (the atomic % of Au was 0.55 and 0.51 for PBG-585 nm (i) and PBG-357 nm (ii) respectively). (D) and (E). High Resolution TEM of 2 and 4 wt.% Au of the PBG Au/TiO2 catalysts indicating the uniform distribution of Au particles at both loads of Au.

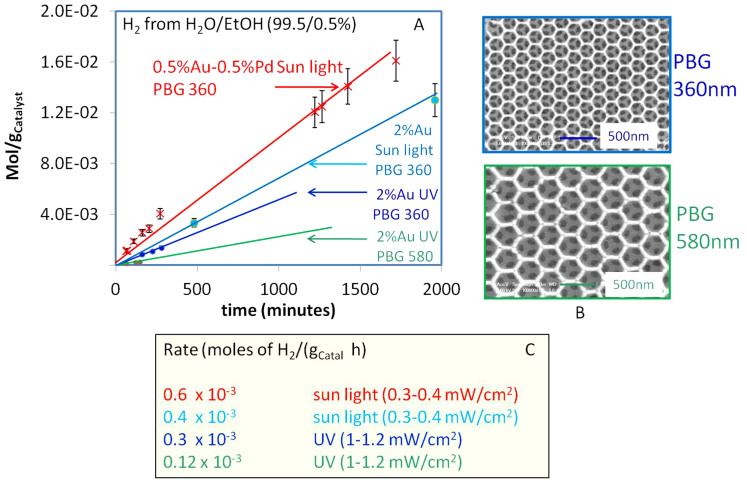

Figure 2 shows scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images for the Au/TiO2 (PBG-357 nm) and Au/TiO2 (PBG-585 nm) samples (supplementary information S3 presents larger SEM images TiO2 PBG-585 nm), and photoreaction data for water splitting to hydrogen in the presence of 0.5 vol.% of ethanol. Ethanol is used in this case as a sacrificial hole scavenger to reduce electron-hole recombination. In preliminary work, we found ethylene glycol, methanol and oxalic acid could also be used successfully as sacrificial agents at concentrations as low as 0.1 vol.%. Ethanol is the preferred sacrificial agent because of its bio-renewable origin, although glycols are also attractive for this purpose as they are common industrial waste products that are often incinerated. Economic analyses indicate that the cost of sacrificial agent (at such a low %) is a small fraction of the cost of the whole process. Both catalysts prepared in this study were highly active for the water splitting reaction. However the Au/TiO2 (PBG-357 nm) photocatalyst was about three times more active than the Au/TiO2 (PBG-585 nm) photocatalyst. For comparison under similar conditions, 2 wt.% Au/TiO2 (anatase) or 4 wt.% Au/TiO2 (anatase) photocatalysts with similar particle size distributions, but not based on inverse opal TiO2 supports5, gave only around one fifth of the activity of the Au/TiO2 (PBG-357 nm) photocatalyst. We attribute the difference in activity to overlap between the PBG of the TiO2 inverse opal support and the electronic band gap of anatase TiO2 ~ 380 nm. It is particularly striking that under direct sunlight the PBG catalysts perform even better than under direct UV, even though the UV flux from the sunlight is weaker. It is worth noting that the TiO2 inverse opal (alone) had negligible photocatalytic activity for H2 production under UV or sunlight. The presence of a metal (or other co-catalysts) fast electron transfer and accumulation from the CB occurs thus further providing available sites for hydrogen ions reduction. In order to decrease the cost we have decreased the amount of Au from 2 wt.% to 0.5 wt.% and combined it with 0.5 wt.% of Pd, both deposited on PBG-357 nm catalyst (supplementary information: S4). The reaction rate was found to be about 0.6 × 10−3 mol/gCatal. h (figure 2) higher than that observed over the 2 wt.% Au/TiO2 PBG-357 nm indicating the potential economical merit of these materials.

Figure 2. Hydrogen production from water using photocatalysts with two different PBG positions under UV light with flux about 1–1.2 mW/cm2 and under direct sun light with UV flux of about 0.3–0.4 mW/cm2.

It is to be noted that the Au/TiO2 with the PBG position close to its electronic band gap is 2 to 3 times more active than an exactly similar material in all respects (except macroporosity and PBG properties) and where the PBG is far from the electronic band gap. Under direct sun light PBG materials are very active despite the lower UV flux. The highest performance was found for the Au-Pd/TiO2 PBG 360 nm. (B). SEM images of the two PBG Au/TiO2 photo-catalysts. Hydrogen production rates are given in (C).

Results of figure 2 demonstrate that the photocatalytic properties of TiO2 inverse opal-based photocatalysts are strongly enhanced when the PBG and electronic absorption of TiO2 are coupled. The equations above indicate that the PBG (λ) for a TiO2 inverse opal is dependent on the macropore diameter (D), the Miller index of the plane from which light is being diffracted (hkl), the incident light angle and the average refractive index of the material (navg). The latter will vary with TiO2 solid volume fraction and the medium filling the macropores. Higher index planes will have photonic band gaps at shorter wavelengths, whilst filling the macropores with water (the reactant and main H2 source in this case) will increase the average refractive index of the inverse opal and red shift the PBG (Supplementary information: S1 and S2). The high hydrogen production rates observed for the photocatalysts prepared in this study, and in particular the Au/TiO2 (PBG-357 nm) sample in sunlight, can be attributed to the fact that light from the sun changes its incident angle during the day. This allows PBGs from different planes in the TiO2 inverse opal structure to overlap with the electronic absorption band of TiO2 (and hence suppress spontaneous emission and electron-hole pair recombination in TiO2). Another possible contributing factor is the presence of the plasmon resonance of Au particles absorbing in the visible (Supplementary information: S5); however the extent of its contribution into the overall rate is not clear yet15,16,17.

Discussion

A detailed analysis of the reaction products was conducted to understand the mechanism(s) of H2 production in the current study. Traces of acetaldehyde, methane and ethylene are seen (table 1). Next to hydrogen in production is CO2 (CO was not detected). Based on this study and previously studied reactions the following steps describe the chemical processes involved.

Table 1. Reaction rates under direct sunlight excitation (UV flux = 0.25–0.35 mW/cm2) over 2 wt.% Au/TiO2 (PBG-357 nm) photocatalyst in presence of 0.5 vol.% of ethanol.

| Product | Reaction rate in mol/(gCatal.min) |

|---|---|

| Hydrogen | 1.5–2 × 10−5 |

| CO2 | 0.1–0.3 × 10−5 |

| C2H4 | ca. 1 × 10−7 |

| CH3CHO | Traces (0.7 × 10−8) |

| CH4 | Traces (0.4 × 10−8) |

Step 1. Dissociative adsorption of ethanol and water occurs on the surface of TiO2 in the presence or absence of light18,19.

s for surface, (a) for adsorbed.

Step 2. Light excitation resulting in electron (e−) - hole (h+) pair formation

Plasmonic Au injection into the CB of TiO2 (up to 103 electrons per 10 nm Au particle (30,000 atom)15.

Step 3. Hole scavenging (two electrons injected per ethoxide into the VB of TiO2) followed by acetaldehyde formation20

Step 4. Electron transfer from the conduction band of TiO2 to hydrogen ions (via Au nanoparticles) resulting in molecular hydrogen formation and hole transfer from one OH species (equation 1b) of water

Step 5. Acetaldehyde decomposition; a slightly exothermic reaction*

Step 6. Water gas shift reaction; a mildly exothermic reaction (ΔH = −41 kJmol−1)

*Competing with step 5 is the coupling of two CH3 radicals to C2H6 that is farther dehydrogenated to C2H4. The Photo-Kolbe process of CH3COOH has been studied in some details over TiO2 single crystals21,22 and powder23. In the process the coupling of two CH3 radicals to C2H6 competes with the coupling of CH3 with H radicals to CH4.

Considering the above steps, the ratio of H2 to CO2 should be 2 (if water is not involved) and 3 (if one water molecule is involved, step 1b); however the H2 to CO2 ratio observed in all runs of this study varied between 6 and 10 depending on the reaction conditions. This indicates that large amounts of hydrogen are produced directly from water rather than simply considering the two electron injections of step 3. Hole trapping (electron injections) by ethanol occurs very fast (a fraction of a nano second24) while the charge carrier disappearance rate is slower (multiples of nano seconds) in anatase TiO2. The plasmonic effect of Au atoms have been observed25 to considerably affect electron transfer where up to 103 electrons are injected into the CB of TiO2 per Au particle of about 10 nm. Also it has been reported that due to the enhancement of the electric field caused by the plasmonic excitation the rate of h+ and e− generation is increased few orders of magnitudes at the interface Au-TiO2. In other words the photoexcited Au particles behave like nano-sized concentrators amplifying the intensity of local photons25. It is to be noted that evidence of a combination of plasmonic effect with the photonic band gap materials of TiO2 has also been seen by other workers. For example, photo-oxidation of organic pollutants26 was shown to be enhanced when Au was deposited on PBG TiO2. In the case of hydrogen production others have designed PBG TiO2 at the Au plasmonic resonance position and found enhancement of the reaction rate27. More specifically the role of plasmonic effect of Au has been studied by others although the exact role is still unclear. Among these studies those involving Au particles in Au-SiO2-Cu2O have clearly indicated enhancement of the reaction rate of the decomposition of methylene blue upon visible light excitation28.

Comparing photoreaction rates reported here with those of other research groups is worthwhile, though tricky as often reactions are conducted with different photon fluxes and energies, and in presence of large amounts of sacrificial agents or additives (to adjust the pH for example). It is also not easy to compare the reaction rate of a photocatalytic system (such as the one in this study) to that of photo-electro-catalytic (PEC) systems. Based on active site type measurement Jaramillo et al.29 estimated Pt based PEC to have a turn over frequency for H2 production close to 1 s−1 while that based on MoS2 is about 50 times weaker. On Mo3S4 PEC materials the evolution of hydrogen when coupled to a p-type Si semiconductor that harvests red photons in the solar spectrum was given and a solar-to-hydrogen efficiency in excess of 10% was obtained30. Under direct sunlight, the hydrogen production rate reported found in this work of about 1 mmol H2/gcatal h for the Au/TiO2 (PBG-357 nm) sample, is to our knowledge the highest ever reported at very low sacrificial agent concentrations (0.5 vol.% ethanol) in systems considering photocatalysis under direct sun light. High rates of H2 production were seen by other workers using Pt/TiO2 (that was treated with H2 for 5 days) but using a H2O:CH3OH molar ratio of 1:1 (i.e. using large amounts of methanol as a sacrificial agent31). The use of such large amounts of a non-renewable sacrificial agent like methanol for H2 production from water is not practical, because methanol itself is made from CO and H2. From the H2 production rate and the amount of UV photons hitting the reactor we calculated that about 80% of the UV photons were converted (supplementary information: S6). The exact quantum yield might be lower as we have neglected contribution from the visible light exciting Au plasmons. Extrapolating this rate to realistic practical conditions is possible to make a comparison with traditional hydrogen production plants based around methane steam reforming. A typical methane steam reforming plant produces 300 tons of hydrogen/day. Assuming eight hours/day of sun light and a catalyst concentration of 0.5 g/L, an area of about 100 km2 would be needed to achieve the same H2 production capacity. Tests conducted for the Au/TiO2 (PBG-357 nm) sample over long periods of time (up to 10,000 minutes) showed stable hydrogen production rates, indicating that they may indeed prove suitable for large scale H2 production. While many work still need to be done to translate this reaction rate to real systems we find that the reaction efficiency and in particular simplicity is high enough to warrant scaling up the process.

In summary, Au/TiO2 photocatalysts, based on inverse opal TiO2 supports, exhibit remarkable photocatalytic activity and stability for photocatalytic water splitting under UV and sunlight. Coincidence of the optical (PBG position) and electronic (TiO2 absorption edge) properties of the TiO2 inverse opal support suppresses electron-hole pair recombination in TiO2, and thus enhances the photocatalytic activity of Au/TiO2 photocatalysts for H2 production from water. Supported gold nanoparticles act as sites for H2 production and may allow visible light excitation of Au/TiO2 photocatalysts via the gold surface plasmon. The Au/TiO2 and Au-Pd/TiO2 (PBG-357 nm) photocatalyst described in this work demonstrated a H2 production rate of about 1 mol H2/kgcat.h from water (with very small amounts of sacrificial agent: ethanol 0.5 vol.%) under sunlight, and excellent operational stability.

Methods

TiO2 inverse opal powders with macropore diameters (D) of 200 nm or 320 nm, and photonic band gaps along the [111] direction in air of 357 nm and 585 nm, respectively, were fabricated by the colloidal crystal template technique. Colloidal crystals composed of monodisperse PMMA colloids (diameters 235 nm or 372 nm, respectively) were prepared using a flow-controlled vertical deposition method32,33 to deposit a PMMA colloidal crystal FILM on a planar substrate and then infiltrated with a TiO2 sol-gel precursor. Careful drying and calcination of the resulting TiO2/PMMA (polymethylmethacrylate) composites selectively removed the PMMA template, yielding 3-dimensionally ordered macroporous TiO2 inverse opals supports. Gold nanoparticles were subsequently deposited on the TiO2 inverse opals supports using the deposition with urea method28. The obtained photocatalysts, labelled Au/TiO2 (PBG-357 nm) and Au/TiO2 (PBG-585 nm), respectively, were then subjected to structural, chemical and photocatalytic characterisation as outlined below.

Photocatalytic tests were conducted under batch conditions. Typically 10–25 mg of catalyst was loaded into a 200 mL Pyrex reactor. Catalysts were reduced with H2 for one hour at 300°C prior to reaction; this was followed by purging with N2 under continuous stirring until all hydrogen was removed. Water (60 mL) was added to the reactor and variable amounts of ethanol (from 0.1 mL to 5 mL). A UV lamp (Spectra-line – 100 W) was used with a cut off filter of 360 nm and above. The UV flux at the front side of the reactor was between about 1–1.2 mW/cm2. Sampling was conducted approximately every 30 minutes. For reactions conducted under sunlight, the same reactor was put under the sun and the UV flux was monitored (the values oscillated between 0.25 and 0.40 mW/cm2 from 10 to 4 pm); catalyst were not stirred under direct sun light excitation. Products were analysed using GCs equipped with thermal conductivity detector TCD and Porapak packed column at 45°C and with N2 as the carrier gas. For O2 detection a GC equipped with TCD was also used but with He as carrier gas.

Transmission electron microscopy studies were performed at 200 kV with a JEOL JEM 2010F instrument equipped with a field emission source. For each sample, more than 300 individual TiO2 and Au nanoparticles were used for particle size determinations. Samples were dispersed in alcohol in an ultrasonic bath and a drop of supernatant suspension was poured onto a carbon coated copper TEM grid for analysis.

SEM images were taken using a Philips XL-30 field emission gun scanning electron microscope (FEGSEM). All micrographs were collected at an electron gun accelerating voltage of 5 kV. Specimens were mounted on black carbon tape and platinum sputter coated for analysis.

The XPS data were collected on a Kratos Axis UltraDLD equipped with a hemispherical electron energy analyser. Spectra were excited using monochromatic Al Kα X-rays (1486.7 eV) with the X-ray source operating at 100 W. Survey scans were collected with a 160 eV pass energy, whilst core level Au 4f scans were collected with a pass energy of 20 eV. The analysis chamber was at pressures in the 10−10 torr range throughout the data collection.

Photoluminescence was collected on a Perkin-Elmer LS-55 Luminescence Spectrometer. The excitation wavelength was set at 310 nm and spectra were recorded over a range of 330–600 nm using a standard photomultiplier. A 290 nm cutoff filter was used during measurements.

UV-Vis absorbance spectra were taken over the range 250–900 nm on a Shimadzu UV-2101 PC spectrophotometer equipped with a diffuse reflectance attachment for powder samples.

UV-Visible reflectance spectra of the TiO2 inverse opal thin films in air and water were collected using an Ocean Optics CCD S-2000 spectrometer fitted with a microscope objective lens coupled to a bifurcated fiber optic cable. A tungsten light source was focused onto the polypyrrole (PPy) films with a spot size of approximately 1–2 mm2. Reflectivity data were recorded with a charge-coupled device CCD detector in the wavelength range of 300–900 nm. Sample illumination and reflected light detection were performed along the surface normal.

Author Contributions

G.I.N.W., V.J. and D.S.W. prepared the photo-catalytic materials, characterized it using XRD, UV-Vis and TEM. A.K.W. and M.A.O. conducted the catalytic experiments and prepared the Au-Pd material. J.L. conducted and analyzed the HRTEM study of Au/TiO2 IO. D.H.A. conducted the HRTEM of Au-Pd/TiO2 IO. H.I. designed the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. G.I.N.W., J.L. also contributed in the writing of the manuscript. All Authors have reviewed the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Manuscript additional figures

References

- Chueh W. et al. High-Flux Solar-Driven Thermochemical Dissociation of CO2 and H2O Using Nonstoichiometric Ceria. Science 330, 1797–1801 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden J. M. & Williams R. H. Electrolytic hydrogen from thin-film solar cell. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 15, 155–169 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- Hanna M. C. & Nozik A. J. Solar conversion efficiency of photovoltaic and photoelectrolysis cells with carrier multiplication absorbers. J. Appl. Phys. 100, 074510–074517 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Sartorel A., Carraro M., Maria F., Prato T. M. & Bonchio M. Shaping the beating heart of artificial photosynthesis: oxygenic metal oxide nano-clusters. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 5592–5603 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch M. et al. The effect of gold loading and particle size on photocatalytic hydrogen production from ethanol over Au/TiO2 nanoparticles. Nature Chemistry 3, 489–492 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Technoeconomic Analysis of Photoelectrochemical (PEC) Hydrogen Production, Direct Technologies under the Department of Energy (DOE) contract number: GS 10F-009J (2009).

- Vernes J. The Mysterious Island, New American Library, New York (1986).

- Fujishima A. & Honda K. Electrochemical Photolysis of Water at a Semiconductor Electrode. Nature 238, 37–38 (1972). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo A. & Miseki Y. Heterogeneous photocatalyst materials for water splitting. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 253–278 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda K., Lu D., Teramura K. & Domen K. Simultaneous photodeposition of rhodium–chromium nanoparticles on a semiconductor powder: structural characterization and application to photocatalytic overall water splitting. Energy Environ. Sci. 3, 471–477 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Ogisu K., Ishikawa A., Teramura K., Toda K., Hara M. & Domen K. Lanthanum–Indium Oxysulfide as a Visible Light Driven Photocatalyst for Water Splitting. Chem. Lett. 36, 854–855 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Yamada Y., Yasuda H., Tayagaki T. & Kanemitsu Y. Photocarrier recombination dynamics in highly excited SrTiO3 studied by transient absorption and photoluminescence spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 121112–121112-3 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Yablonovitch E. Inhibited Spontaneous Emission in Solid-State Physics and Electronics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 58, 2059–2062 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The VB electronic structure was monitored and showed identical Au5f and O2p contributions.

- Du L., Furube A., Yamamoto K. Hara K., Katoh R. & Tachiya M. Plasmon-Induced Charge Separation and Recombination Dynamics in Gold−TiO2 Nanoparticle Systems: Dependence on TiO2 Particle Size. J. Phys. Chem. C 113, 6454–6462 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Seh Z. W. et al. Janus Au-TiO2 Photocatalysts with Strong Localization of Plasmonic Near-Fields for Efficient Visible-Light Hydrogen Generation. Adv. Mater. 24, 2310–2314 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idriss H. & Wahab A. K. Photoreaction of water to hydrogen on gold-palladium deposited on TiO2. European Procedure (Patents) (12CHEM0012-EP-EPA) filed at the Patent Office on 03-09-2012 as Serial Number 12006217.9. (2012).

- Nadeem M. A. et al. Photoreaction of ethanol on Au/TiO2 anatase. Comparing the micro to nano particle size activities of the support for hydrogen production. J. PhotoChem & PhotoBio A: Chemicals 216, 250–255 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Jayaweera P. M., Quah E. L. & Idriss H. Photoreaction of Ethanol on TiO2(110) Single-Crystal Surface. J. Phys. Chem. C 111, 1764–1769 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Miller B. R., Majoni S., Memming R. & Meissner D. Particle Size and Surface Chemistry in Photoelectrochemical Reactions at Semiconductor Particles. J. Phys. Chem. B, 101, 2501–2507 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Wilson J. N. & Idriss H. Effect of Surface Reconstruction of TiO2(001) Single Crystal on the Photoreaction of Acetic Acid. J. Catal. 214, 46–52 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Wilson J. N. & Idriss H. Structure-Sensitivity and Photo-catalytic Reactions of Semiconductors. Effect of the Last Layer Atomic Arrangement. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 11284–11285 (2002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muggli D. S. & Falconer J. L. Parallel Pathways for Photocatalytic Decomposition of Acetic Acid on TiO2. J. Catal. 187, 230–237 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Sabio E. M., Chi M., Browning N. D. & Osterloh F. E. Photocatalytic Water Oxidation with Nonsensitized IrO2 Nanocrystals under Visible and UV Light. Langmuir 26, 7254–7267 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linic S., Christopher P. & Ingram D. B. Plasmonic-metal nanostructures for efficient conversion of solar to chemical energy. Nature Materials 10, 911–921 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Yu H., Chen S., Quan X. & Zha H. Integrating Plasmonic Nanoparticles with TiO2 Photonic Crystal for Enhancement of Visible-Light-Driven Photocatalysis. Environ. Sci. & Technol. 46, 1724–1730 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Zhang L., Hedhili M. N., Zhang H. & Wang P. Plasmonic Gold Nanocrystals Coupled with Photonic Crystal Seamlessly on TiO2 Nanotube Photoelectrodes for Efficient Visible Light Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting. Nano Lett. 13, 14–20 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushing S. K. et al. Photocatalytic Activity Enhanced by Plasmonic Resonant Energy Transfer from Metal to Semiconductor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 15033–15041 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaramillo T. F. et al. Identification of Active Edge Sites for Electrochemical H2 Evolution from MoS2 Nanocatalysts. Science 317, 100–103 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Y. et al. Nature Materials 10, 434–438 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Liu L., Yu P. Y. & Mao S. S. Increasing Solar Absorption for Photocatalysis with Black Hydrogenated Titanium Dioxide Nanocrystals. Science 331, 746–750 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z. & Zhao X. S. Opal and Inverse Opal Fabricated with a Flow-Controlled Vertical Deposition Method. Langmuir 21, 4717–4723 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z. & Zhao X. S. Flow-Controlled Vertical Deposition Method for the Fabrication of Photonic Crystals. Langmuir 20, 1524–1526 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Manuscript additional figures