Abstract

Terfezia boudieri Chatin (Scop.) Pers., is a famous macrofungus in the world as well as in Turkey for its pleasant aroma and flavour. People believe that this mushroom has some medicinal properties. Therefore, it is consumed as food and for medicinal purposes. Chloroform, acetone and methanol extracts of T. boudieri were tested to reveal its antimicrobial activity against four Gram-positive and five Gram-negative bacteria, and one yeast using a micro dilution method. In this study, the highest minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) value was observed with the acetone extract (MIC, 4.8 µg/mL) against Candida albicans. Maximum antimicrobial effect was also determined with the acetone extract (MIC, 39–78 µg/mL). The scavenging effect of T. boudieri on 2, 2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radicals was measured as 0.031 mg/mL at 5 mg/mL concentration, and its reducing power was 0.214 mg/mL at 0.4 mg/mL. In addition, the phenolic contents were determined as follows: the catechin was 20 mg/g, the ferulic acid was 15 mg/g, the p-coumaric acid was 10 mg/g, and the cinnamic acid was 6 mg/g. The results showed that T. boudieri has antimicrobial activity on the gram negative and positive bacteria as well as yeast, and it also has a high antioxidant capacity. Therefore, T. boudieri can be recommended as an important natural food source.

Keywords: Gram positive and negative bacteria, medical mushroom, scavenging effect, Terfezia boudieri

Introduction

Edible mushrooms have some important protein ingredients such as single cell proteins (SCP). Additionally, mushrooms do not contain starch and they have very low amount of sugar. Fat contents of mushrooms are low in total amount but they are rich in essential fatty acids. The other important features of mushrooms are that they have ergosterol, they could be converted by the body into vitamin D, and do not contain cholesterol. Certain species of edible, inedible and poisonous mushrooms are known to have important medicinal properties, and their extracts are also used for possible treatments of some diseases in the world. A few species, such as, Lentinula edodes (shiitake), Grifola frondosa (maitake), Ganoderma lucidum (mannentake) and Cordyceps spp. have a history of medicinal usage in parts of Asia. The studies have indicated that mushrooms have cardiovascular, anticancer, antiviral, antibacterial, anti-parasitic, anti-inflammatory, hepatoprotective, and glycaemic activities (Yang et al., 2002; Jeong et al., 2009; Jua et al., 2010). Antioxidants, or the molecules that have a scavenging effect on DPPH radicals, are known as potentially protective substances (Ramirez-Anguiano et al., 2007). This protective effect is mainly attributed to well-known antioxidants such as ascorbic acid, tocopherols and β carotenes, but plant phenols also play an important role.

T. boudieri has a particular aroma and taste, and it is known as “Desert Truffle” in the Mediterranean countries. It is a very popular species. Although T. boudieri is an important food source, there is no conclusive report concerning its antimicrobial effects, antioxidant activity or fatty acid composition in Turkey.

Material and Methods

Collection of T. boudieri samples

The samples were collected from Karaman-Mara district, under Helianthemum salicifolium, 08.04.2001, and its fungarium number is HD1145. The species identification was performed as described in the literature (Astier, 1998). The fruiting bodies of mushroom samples were dried in a dehydrator at 37–40°C for 5 days. A stock sample of the species was also deposited at the Fungarium of the Mushroom Application and Research Centre, Selçuk University, Konya, Turkey.

Antimicrobial activities

Preparation of the extracts

Powdered fungus sample (30 g) was extracted with 250 mL of chloroform in a glass beaker for 8 h at 55°C on a hot plate. The resultant extract was concentrated using a rotary evaporator at 40°C and low pressure, and the desired phase was separated from the crude extract with chloroform. Later, the residue was extracted with acetone and methanol, respectively. After extractions were completed, all the semi-solid extracts were lyophilised. The lyophilised extracts were dissolved in DMSO: PBS (1:1) at a 100.000 µg/mL concentration. These extracts were filtered through a sterile filter (0.45 µm) and stored at 4°C.

Test microorganisms

All the microorganisms were obtained from the Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Selçuk University. Four Gram-positive bacteria (Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6633, Listeria monocytogenes type 2 NCTC 5348 and Streptococcus pyogenes ATCC 19615) and five Gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli ATCC 35218, Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 10031, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 15442, Proteus vulgaris ATCC 7829 and Salmonella enteritidis RSHMB) were chosen as test bacteria. Candida albicans ATCC 1023 was chosen as yeast.

Antimicrobial assay

Brain Heart Infusion Broth (BHIB, Oxoid) was used to cultivate the bacteria, and Malt Extract Broth (MEB, Difco) was used for the yeast. The bacterial cultures were adjusted to 105 Cfu/mL. The concentration of the yeast was adjusted to 104 Cfu/mL.

Determination of the antimicrobial activity by the micro dilution method

T. boudieri extract in the stock solutions was prepared at a 20000 µg/mL concentration in PBS: DMSO (1:1). MHB (100 µL) was dispensed into each well of a flat-bottom, 96-well microtiter plate. The serial ½ dilutions (100 µL) of T. boudieri chloroform, acetone, and methanol extracts were prepared separately. Finally, a dilution series of each extract were prepared from 20000 µg/mL to 0.305 µg/mL. Then, 100 µL of each bacterial suspension were added into each well containing the MHB and the mushroom extract mixture. This procedure was also repeated for the yeast in different plate wells. The absorbance of the plates was measured using an ELISA reader at 630 nm (EL × 800). The lowest concentration that produced an inhibitory effect was recorded as the MIC for each extract as described by Devienne & Raddi (2002) with some modifications. Ampicillin (100 µg/mL concentration) for bacteria and Amphotericin B (50 µg/mL concentration) for yeast were used as positive controls. Each experiment was conducted in triplicate.

Antioxidant activities

A hundred grams of the powdered sample were extracted with stirring in methanol at 60°C for 6 h in a Soxhlet apparatus. The extract was then filtered through Whatman No. 4 filter paper and concentrated under a vacuum at 45°C using a rotary evaporator. The extracts were then lyophilised and stored in the dark at 4°C until it was used.

Scavenging effect on DPPH radicals

0.5 mL of the methanol extract in a range of concentrations (0.5–5 mg/mL) was added to 3 mL of a DPPH radical solution in methanol (the final concentration of DPPH was 0.2 mM). The mixture was shaken vigorously and left to stand for 30 min in the dark, and the absorbance was then measured at 517 nm against a blank using the Hitachi U-2001 spectrophotometer (Shimada et al., 1992). BHT and BHA were used as standard controls. The β-carotene-linoleic acid assay was performed as described by Taga et al. (1984).

Reducing power

Extract (0.04–0.4 mg/mL) in methanol (2.5 mL) was mixed with 2.5 mL of 200 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.6) and 2.5 mL of 1% potassium ferricyanide, and the mixture was incubated at 50°C for 20 min. Next, 2.5 mL of 10% trichloroacetic acid (w/v) was added, and the mixture was centrifuged at 200g for 10 min. The upper layer (5 mL) was mixed with 5 mL of deionised water and 1 mL of 0.1% ferric chloride. Finally, the absorbance was measured at 700 nm against a blank in a Hitachi U-2001 spectrophotometer.

Determination of the phenolic composition of T. boudieri

The total phenolic content of the methanol crude extract was determined by the Folin-Ciocalteu method with some modifications according to Singleton & Rossi (1965). The phenolic substances were determined as described by Maltas & Yildiz (2011). Gallic acid, catechin, caffeic acid, p-coumaric acid, ferulic acid, cinnamic acid and quercetin (Sigma-Aldrich) were analysed as standard phenolic structures. The samples were run in triplicate.

Results and Discussion

Antimicrobial activity results

According to Craig (1998), to evaluate antimicrobial activity, MIC values should be measured from the 4th through the 16th dilutions. The antimicrobial effects of T. boudieri against bacteria and yeast were measured in accordance with the following ranges (Gülay, 2002; Morales et al., 2008):

1-MIC values are lower than 100 µg/mL = antimicrobial activity is high;

2-MIC values are between 100 µg/mL and 500 µg/mL = antimicrobial activity is moderate;

3-MIC values are between 500 µg/mL and 1000 µg/mL = antimicrobial activity is weak;

4-MIC values are more than 1000 µg/mL = no antimicrobial effect.

In accordance with these ranges, the antimicrobial results are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

MIC values of T. boudieri extracts (µg/mL)

| Microorganisms | Chloroform | Acetone | Methanol |

| B. subtilis | 78 (< 100) | 39 (< 100) | 156 (100–500) |

| S. aureus | 78 (< 100) | 39 (< 100) | 312.5 (100–500) |

| L. monocytogenes | 78 (< 100) | 39 (< 100) | 625 (>500) |

| S. pyogenes | 156 (100–500) | 312.5 (100–500) | 312.5 (100–500) |

| C. albicans | 156 (100–500) | 4.8 (< 100) | 312.5 (100–500) |

| E. coli | 78 (< 100) | 39 (100–500) | 312.5 (100–500) |

| K. pneumonia | 78 (100–500) | 39 (< 100) | 156 (100–500) |

| P. aeruginosa | 78 (< 100) | 39 (< 100) | 312.5 (100–500) |

| P. vulgaris | 78 (< 100) | 78 (< 100) | 625 (>500) |

| S. enteritidis | 78 (< 100) | 39 (< 100) | 312.5 (100–500) |

*-< 100 µg/ml = High, 100 – 500 µg/ml = Moderate, 500 – 1000 µg/ml = Low

The maximum inhibitory effect on the test microorganisms was observed with the acetone extract (4.8 µg/mL in the 13th dilution) against C. albicans. Overall, the acetone extract exhibited the maximum antimicrobial effect with values generally lower than 100 µg/mL, placing it in the high category (MIC values, 78 µg/mL in the 10th dilution), except S. pyogenes (312.5 µg/mL). The effects of the chloroform extract against test microorganisms are of high and moderate activity (MIC values, 78 and 156 µg/mL in the 6th and 7th dilutions, respectively). The lowest antimicrobial effect was observed in the methanol extracts (MICs, 156 µg/mL to 625 µg/mL). In general, acetone and chloroform extracts of T. boudieri were found to be more effective than methanol extracts against bacteria and yeast. The most effective MIC concentrations of the extracts were typically measured between the 6th and 10th dilutions.

The current results were also confirmed by previous studies. The crude water extract of T. boudieri was used to treat eye disease, and it was also effective against S. aureus (Gücin & Dülger, 1997). According to Yoon et al. (1994), Ganoderma lucidum had a good antimicrobial effect against Proteus vulgaris (MIC, 1.25 mg/mL) and Escherichia coli (MIC, 1.75 mg/mL), and six species of bacteria were determined to have MIC values higher than 5 mg/mL. In the present study, MIC values were generally measured between 78 µg/mL and 312.5 µg/mL, and our results are better than those of Yoon et al (15). Gbolagade et al. (2007) studied the antimicrobial effects of some fungal species using disc diffusion and micro dilution methods. The highest antibacterial inhibitory activity (24.0 mm) was recorded with the purified extract (PRE) of Polyporus giganteus against E. coli, and the second widest inhibition zone (22.0 mm) was recorded with the PRE of Pleurotus floridanus against K. pneumonia in their study. Except for the extracts of P. tuber-regium, none of the tested macrofungi was able to inhibit the growth of P. aeruginosa. Overall, the antifungal activities of these higher fungi were low, and P. giganteus and Termitomyces robustus only inhibited the growth of C. albicans with values that were not statistically significant. A study conducted on antimicrobial effect of Russula delica by Yaltirak et al. (2009) showed that while the highest inhibitory activity was measured against S. sonnei RSKK 8177, in contrast, the weakest inhibitory activity was measured against P. aeruginosa ATCC 29212 and S. enteritidis 171. In the present study, all the extracts exhibited higher antibacterial activity against P. aeruginosa and S. enteritidis more than the extract of R. delica as reported by Yaltirak et al. (2009). In the present study too, the highest MIC concentration (4.8 µg/mL) was recorded with the acetone extract against C. albicans. However, higher MIC concentrations (39–78 µg/mL) were observed from acetone extract.

The current results are similar or more effective than these literatures. To the best of our knowledge, there were previously no reports on the antimicrobial effects of T. boudieri using micro dilution method, and this result has been reported here for the first time.

Antioxidant activity results

The scavenging effects on DPPH radicals

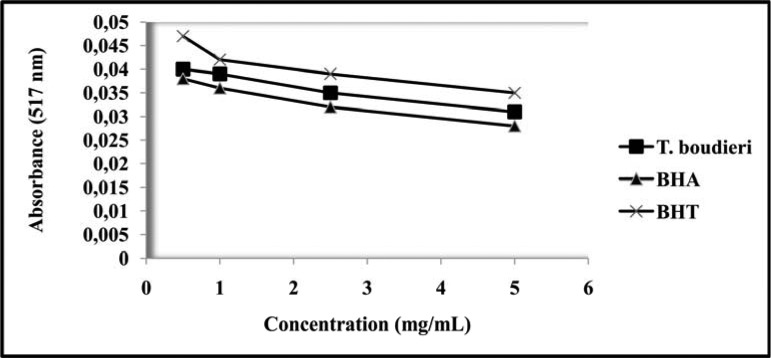

The DPPH radical scavenging effects of T. boudieri, as well as those of the BHA and BHT controls, rose as the increased concentration from 0.5 to 5 mg/mL (Fig. 1). The scavenging values at 0.5 mg/mL concentration were 0.04 mg/mL for T. boudieri, 0.047 mg/mL for BHT and 0.038 mg/mL for BHA, while the scavenging values at 5 mg/mL were 0.031mg/mL for T. boudieri, 0.035 mg/mL for BHT and 0.028 mg/mL for BHA. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the scavenging effect of T. boudieri extract on DPPH radicals rose with increasing concentrations.

Figure 1.

The DPPH radical scavenging effects of T. boudieri, BHA and BHT

The IC50 value of T. boudieri extract was lower than BHA and higher than BHT. The IC50 values were 0.58 mg/mL for T. boudieri, 0.43 mg/mL for BHA and 0.72 mg/mL for BHT (Figure 2). A lower IC50 value indicates higher antioxidant activity (Pourmorad et al., 2006), so the antioxidant capacity of T. boudieri is higher than BHA.

Figure 2.

IC50 values of T. boudieri, BHA and BHT

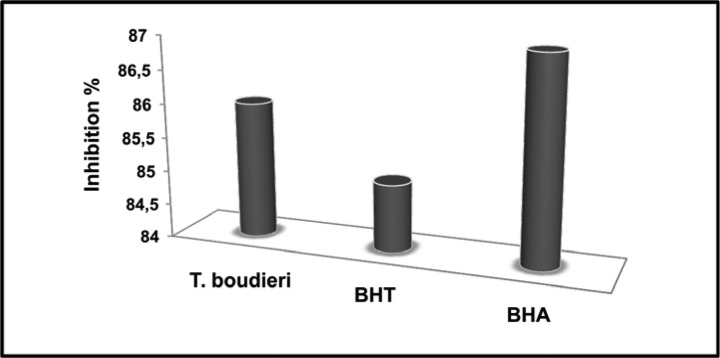

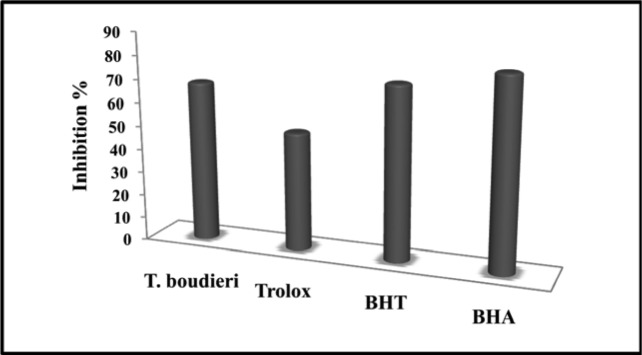

The inhibition values of T. boudieri extract and the standards on the DPPH radicals at 0.5 mg/mL concentration were 55% for T. boudieri, 60.60% for BHA and 53% for BHT (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Inhibition values of T. boudieri and standards on the DPPH radicals

In previous studies, the scavenging effects of mushroom extracts ranged from 36–96% at a concentration of 5–10 mg/mL. Because different methods and concentrations were used in the literature, there was no standard level for measuring scavenging effects. Some studies can be summarised as follows: the scavenging effect of Volvariella volvacea was measured as 57.8% at 9 mg/mL concentration (Cheung et al., 2003). Mau et al. (2004) used 10 mg/mL concentration for their studies, which reported scavenging effects of 78.8%, 79.9%, and 94.1% for Termitomyces albuminosus, Grifola frondosa and Morchella esculenta, respectively.

Additionally, Lee et al. (2008) studied the fruiting body and mycelia of Hypsizygus marmoreus with hot water and methanol extraction. According to their results, the scavenging effects of the fruiting body and mycelia ethanol extracts at 5 mg/mL concentration were both 75.5%, while the scavenging effects of the fruiting body and mycelia hot water extracts were 36.8% and 55.5%, respectively. The scavenging effect of R. delica was 26% at 10 mg/mL concentration (Yaltirak et al., 2009). Compared with the inhibition values reported in these studies, T. boudieri extract was effective at a much lower concentration.

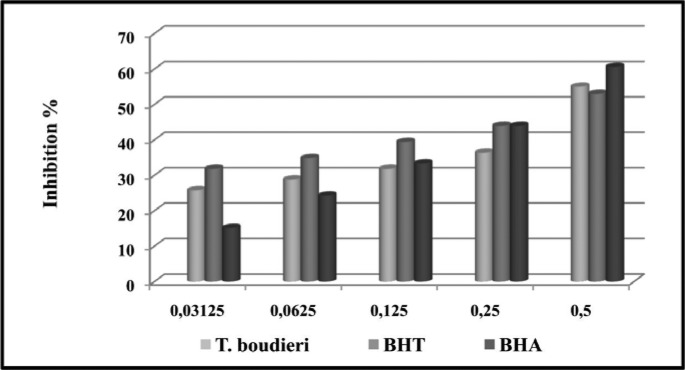

β-Carotene-linoleic acid assay

The inhibition values of T. boudieri were determined to be higher than Trolox, but similar to BHT and lower than BHA. T. boudieri extract, BHT, BHA and Trolox exhibited 68.6%, 73.7%, 80.8%, and 50.51% inhibition, respectively (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The inhibition % graph

According to the literature, the inhibition values of mushroom extracts vary from 50% to 96% at the different concentrations. The antioxidant activities of methanolic extracts of young and mature Agaricus brasiliensis Fr. were evaluated with β-carotene, and were found to inhibit oxidation 92% at 0.2 mg/mL concentration (Soares et al. 2009). Gürsoy et al. (2009) studied with seven Morchella species and found that M. esculenta var. umbrina and M. angusticeps were to be the most active species (96.89% and 96.88%, respectively, at 4.5 mg/mL concentration). Sarikürkcü et al. (2010) studied antioxidant activity of Amanita caesarea, Clitocybe geotropa and Leucoagaricus pudicus, and they discovered that L. pudicus possessed the highest oxidation level (81.8% at 25.5 mg/mL concentration). It was followed by A. caesarea (70.1%) and C. geotropa (61.3%). In comparison with previous studies, T. boudieri had a high oxidation level even at a low concentration (68.96% at 2.284 mg/mL).

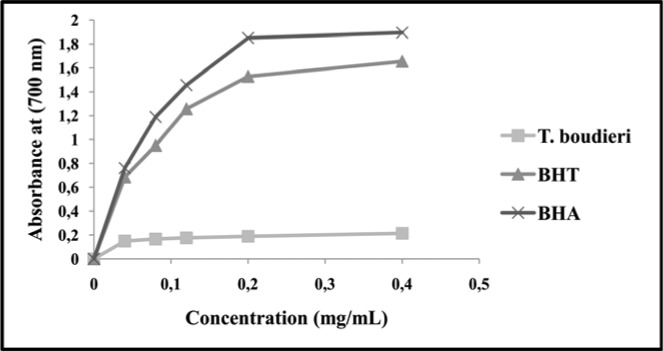

Reducing power

The reducing power of T. boudieri extract showed a parallelism with its increased concentration (Fig. 5). The highest reducing power was observed with BHA (1.895 mg/mL); it was followed by BHT (1.654 mg/mL) and T. boudieri (0.214 mg/mL) from 0.04 mg/mL to 0.4 mg/mL concentrations.

Figure 5.

Absorbance values of T. boudieri and synthetic antioxidant compounds

Yang et al. (2002) observed that the reducing power of mushrooms exceeded 1.28 mg/mL at 40 mg/mL concentration, with the reducing power of each species ordered from the highest to the lowest: Pleurotus ostreatus ≈ P. cystidiosus > Lentinula edodes > Flammulina velutipes. According to Elmastaş et al. (2007), the reducing power of R. delica and Verpa conica extracts were 1.32 µg/mL and 1.22 µg/mL, respectively, at 200 µg/mL concentration. At 20 mg/mL concentration, the reducing powers of A. caesarea, C. geotropa and L. pudicus were 1.5 mg/mL, 1.2 mg/mL, and 1.3 mg/mL, respectively (Sarikürkcü et al., 2010). In comparison with the studies described above, T. boudieri possessed a high reducing power at a low concentration.

Total phenolic and phenolic compounds of T. boudieri

The amount of phenolic compounds in the methanol extract of T. boudieri was determined to be 0.21 mg/g gallic acid equivalents. Some selected phenolic acids and flavonoids of the extract were separated and compared with authentic standards using HPLC for identification. The phenolic composition of T. boudieri was reported here for the first time (Table 2). Seven components from T. boudieri were analysed, and four of them were identified as catechin, p-coumaric acid, ferulic acid and cinnamic acid. Catechin was the predominant phenolic acid with a value of 20 mg/g, it was followed by ferulic acid at 15 mg/g, p-coumaric acid at 10 mg/g and cinnamic acid at 6 mg/g. However, the extract did not contain any flavonoids, such as quercetin, caffeic acid and gallic acid.

Table 2.

Phenolic compounds of T. boudieri

| Phenolic compounds | Composition (mg/g) | |

| 1 | Caffeic acid | ND |

| 2 | Catechin | 20 |

| 3 | Cinnamic acid | 6 |

| 4 | Ferulic acid | 15 |

| 5 | Gallic acid | ND |

| 6 | p-coumaric acid | 10 |

| 7 | Quercetin | ND |

Antioxidant, antimicrobial, antiallergy and anticancer effects of catechin were reported in some previous studies (Kondo et al., 2000; Shimamura et al., 2007). Catechin was found in R. delica at 5.33 mg/g by Yaltirak et al. (2009). In the present study, it was found at 20 mg/g and this ratio is quite high. Antimicrobial activities were already appearing in high-impact in the present study, and this can be related with high catechin level.

Ferulic acid, like many phenols, is an antioxidant ‘in vitro’ in the sense that it is reactive towards free radicals, such as reactive oxygen species (ROS). ROS and free radicals are implicated in DNA damage, cancer, and accelerated cell aging. Ferulic acid may be effective at preventing cancer induced by exposure to carcinogenic compounds (Kampa et al., 2004).

Coumarin derivatives are important substances for human health. They have anti-thrombotic, anti-inflammatory, and vasodilatory effects as well as antiviral and antimicrobial activities (Cowan, 1999).

Cinnamic acids are common representatives of a wide group of phenylpropane-derived compounds that are in the highest oxidation state. Cinnamic acids are effective against viruses, bacteria and fungi (Cowan, 1999).

Conclusion

The present results indicate that economically important and edible mushrooms may display significant antioxidant and antimicrobial features, and they are a good source of fatty acids. Therefore, future studies in this area should be extended to other economically important and edible mushrooms.

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to the Foundation for TÜBİTAK (TBAG/109T584) and Scientific Research Projects (BAP) Coordinating Office (BAP/08201036-BAP10701001) at Selçuk University for their financial support of this study.

References

- 1.Astier J. Truffes blanches et noires. Marseille: Louis-Jean, Gap; 1998. pp. 48–49. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheung LM, Cheung Peter C K, Vincent EC. Antioxidant activity and total phenolics of edible mushroom extracts. Food Chem. 2003;81:249–255. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cowan MM. Plant products as antimicrobial agents. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:564–582. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.4.564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Craig WA. Pharmocokinetic/pharmacodynamic parameters: rationale for antibacterial dosing of mice and men. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1–12. doi: 10.1086/516284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Devienne KF, Raddi MSG. Screening for antimicrobial activity of natural products using a microplate photometer. Braz J Microbiol. 2002;33:166–168. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elmastaş M, Işıldak â, Türkekul İ, Temur N. Determination of antioxidant activity and antioxidant compounds in wild edible mushrooms. J Food Compos Anal. 2007;20:337–345. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gbolagade J, Kigigha L, Ohimain E. Antagonistic effect of extracts of some Nigerian higher fungi against selected pathogenic microorganisms. Am-Euras J Agric & Environ Sci. 2007;2:364–368. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gücin F, Dülger B. Yenen ve antimikrobiyal aktiviteleri olan keme mantarı (Terfezia boudieri Chatin) üzerinde araştırmalar. Ekoloji. 1997;7:27–33. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gülay Z. Antibiyotik duyarlılık testlerinin yorumu. Tur Toraks Der. 2002;31:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gürsoy N, Sarıkürkçü C, Cengiz M, Solak MH. Antioxidant activities, metal contents, total phenolics and flavonoids of seven Morchella species. Food Chem Toxicol. 2009;47:2381–2388. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2009.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeong HK, Kim SJ, Hae-Ryong P, Jong IC, Cheoul YJ, Chang KN, Seung CL. The different antioxidant and anticancer activities depending on the colour of oyster mushrooms. J Med Plants Res. 2009;3:1016–1020. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jua HK, Chung HW, Hong SS, Park JH, Lee J, Kwon SW. Effect of steam treatment on soluble phenolic content and antioxidant activity of the Chaga mushroom (Inonotus obliquus) Food Chem. 2010;119:619–625. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kampa M, Alexaki VI, Notas G, Nifli AP, Nistikaki A, Hatzoglou A, Bakogeorgou E, Kouimtzoglou E, Blekas G, Boskou D, Gravanis A, Elias Castanas E. Antiproliferative and apoptotic effects of selective phenolic acids on T47D human breast cancer cells: potential mechanisms of action. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6:63–74. doi: 10.1186/bcr752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kondo K, Kurihara M, Fukuhara K, Tanaka T, Suzuki T, Miyata N, Toyoda M. Conversion of procyanidin B-type (catechin dimer) to A-type: evidence for abstraction of C-2 hydrogen in catechin during radical oxidation. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:485–488. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee YL, Jian SY, Lian PY, Mau JL. Antioxidant properties of extracts from a white mutant of the mushroom Hypsizigus marmoreus. J Food Compos Anal. 2008;212:116–124. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maltas E, Yildiz S. Distribution of secondary metabolites in Brassica napus genotypes. J Food Biochem. 2011;35:1071–1082. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mau JL, Chang CN, Huang SJ, Chen CC. Antioxidant properties of methanolic extracts from Grifola frondosa, Morchella esculenta and Termitomyces albuminosus mycelia. Food Chem. 2004;87:111–118. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morales G, Paredes A, Sierra P, Loyola LA. Antimicrobial activity of three baccharis species used in the traditional medicine of northern Chile. Molecules. 2008;13:790–794. doi: 10.3390/molecules13040790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pourmorad F, Hosseinimehr SJ, Shahabimajd N. Antioxidant activity, phenol and flavonoid contents of some selected Iranian medicinal plants. Afr J Biotechnol. 2006;5:1142–1145. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramirez-Anguiano AC, Santoyo S, Reglero G, Soler-Rivas C. Radical scavenging activities, endogenous oxidative enzymes and total phenols in edible mushrooms commonly consumed in Europe. J Sci Food Agr. 2007;87:2272–2278. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarikürkcü C, Tepe B, Semiz DK, Solak MH. Evaluation of metal concentration and antioxidant activity of three edible mushrooms from Mugla, Turkey. Food Chem Toxicol. 2010;48:1230–1233. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2009.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shimada K, Fujikawa K, Yahara K, Nakamura T. Antioxidative properties of xanthan on the autoxidation of soybean oil in cyclodextrin emulsion. J Agr Food Chem. 1992;40:945–948. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shimamura T, Zhao W-H, Hu Z-Q. Mechanism of action and potential for use of tea catechin as an anti-infective agent. Anti-Infect Agents in Medicinal Chemistry. 2007;6:57–62. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singleton VL, Rossi JA. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. Am J Enol Viticult. 1965;16:144–158. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soares AA, Marques de Suza CG, Daniel FM, Ferrari GP, Gomes da Costa SM, Peralta RM. Antioxidant activity and total phenolic content of Agaricus brasiliensis (Agaricus blazei Murril) in two stages of maturity. Food Chem. 2009;112:775–781. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taga MS, Miller EE, Pratt DE. Chia seeds as a source of natural lipid antioxidants. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1984;61:928–931. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yaltirak T, Aslim B, Ozturk S, Alli H. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Russula delica. Fr Food Chem Toxicol. 2009;47:2052–2056. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2009.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang JH, Linb HC, Maub JL. Antioxidant properties of several commercial mushrooms. Food Chem. 2002;77:229–235. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoon SY, Eo SK, Kim YS, Lee CK, Han SS. Antimicrobial activity of Ganoderma lucidum extract alone and in combination with some antibiotics. Arch Pharm Res. 1994;7:438–442. doi: 10.1007/BF02979122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]