Abstract

The clinical pathological characteristics of 3969 adult patients with chronic atrophic gastritis were retrospectively studied. The positivity of intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia in atrophic gastric specimens increased with age; however, H. pylori positivity and inflammatory activity decreased significantly with increased age. H. pylori infection was present in 21.01% of chronic atrophic gastritis patients, and 92.33% of the subjects with H. pylori infection were found to have simultaneous inflammatory activity. The intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia positivity markedly increased as the degree of gastric atrophy increased. In conclusion, the incidence of H. pylori infection decreased with age and correlated significantly with inflammatory activity in atrophic gastritis patients. The intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia positivity notably increased as the degree of gastric atrophy increased. Large population-based prospective studies are needed to better understand the progression of CAG.

1. Introduction

Chronic atrophic gastritis (CAG) is a histopathologic entity characterized by chronic inflammation of the gastric mucosa with loss of gastric glandular cells. CAG, intestinal metaplasia (IM), and epithelial dysplasia (ED) of the stomach are common and are associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer. CAG and IM are considered to be precancerous conditions. ED represents the penultimate stage of the gastric carcinogenesis sequence, defined as histologically unequivocal neoplastic epithelium without evidence of tissue invasion, and is thus a direct neoplastic precancerous lesion. ED is characterized by cellular atypia reflective of abnormal differentiation and disorganized glandular architecture.

Helicobacter pylori are Gram-negative bacteria that colonize the human gastric epithelium and represent one of the most common human infections worldwide. H. pylori infection is usually contracted in the first few years of life, and its prevalence increases with older age and lower socioeconomic status during childhood [1]. This infection is the primary inducer of CAG, IM, and ED. More than half of all humans have H. pylori colonies in their stomachs; however, only a minority of H. pylori-infected individuals develop cancer of the stomach [2]. Haziri et al. [3] reported that the prevalence of H. pylori infection was high in patients with CAG (66.0%), IM (71.7%), and gastric dysplasia (71.4%). In the present study, the clinical and histopathological characteristics of 3969 CAG patients from our hospital were retrospectively studied, and the relationship between H. pylori infection and gastric precancerous conditions was investigated. The results of this study will provide a greater understanding of CAG.

2. Methods

Patients with CAG diagnosed by endoscopy and histological examination from 2007 to 2012 in the First Affiliated Hospital of the College of Medicine at Zhejiang University were included in the study. One or two biopsies from the antrum were taken, and the slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Cases in which H. pylori were identified in any of the biopsy specimens were considered positive. The presence of atrophy was assessed according to the updated Sydney System classification [4].

Fisher's exact test was used to compare the proportions of different characteristics between groups, and P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

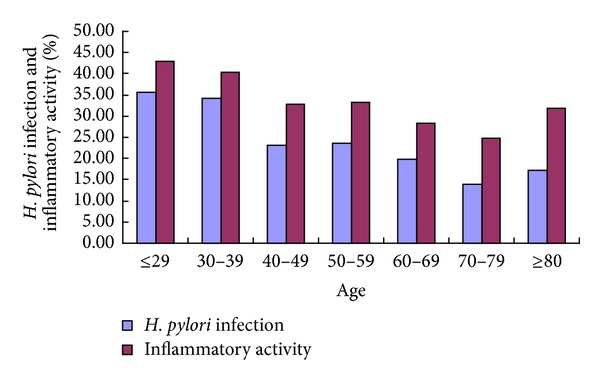

There were 3969 adult patients (2051 males and 1918 females) with CAG enrolled, whose age ranged from 18 to 94 years. The distribution of the different stages of CAG, IM, and ED of the stomach according to age is shown in Table 1. In 196 cases of young adults (≤40 years), 2639 cases of middle-aged adults (41−65 years), and 1134 cases of older adults (≥66 years), the H. pylori infection (33.67%, 21.94%, and 16.67%), and inflammatory activity (39.8%, 31.45%, and 26.7%) decreased with age (also see in Table 1 and Figure 1). The presence of IM with young adulthood, middle and old age (80.61%, 83.86%, and 86.07%) and ED (2.04%, 3.07%, and 4.32%) in CAG patients increased with age (see also in Table 1).

Table 1.

The clinical and pathological characteristics of 3969 cases of atrophic gastritis according to age group.

| Age (years) | Cases (N) | Gender | Gastric atrophy | Intestinal metaplasia | Dysplasia | H. pylori infection | Inflammatory activity | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Mild | Moderate | Severe | None | Mild | Moderate | Severe | None | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | ||

| ≤29 | 28 | 15 | 13 | 20 | 5 | 3 | 8 | 10 | 6 | 4 | 27 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 10 | 16 | 12 |

| 30–39 | 129 | 75 | 54 | 72 | 52 | 5 | 20 | 35 | 55 | 19 | 128 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 85 | 44 | 77 | 52 |

| 40–49 | 605 | 333 | 272 | 380 | 212 | 13 | 104 | 158 | 270 | 73 | 585 | 19 | 1 | 0 | 465 | 140 | 407 | 198 |

| 50–59 | 1296 | 637 | 659 | 747 | 507 | 42 | 224 | 331 | 529 | 212 | 1259 | 32 | 5 | 0 | 991 | 305 | 864 | 432 |

| 60–69 | 1106 | 567 | 539 | 634 | 417 | 55 | 142 | 306 | 475 | 183 | 1067 | 29 | 8 | 2 | 887 | 219 | 794 | 312 |

| 70–79 | 689 | 350 | 339 | 388 | 269 | 32 | 107 | 192 | 271 | 119 | 657 | 26 | 3 | 3 | 593 | 96 | 519 | 170 |

| ≥80 | 116 | 74 | 42 | 50 | 52 | 14 | 17 | 25 | 46 | 28 | 112 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 96 | 20 | 79 | 37 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Total | 3969 | 2051 | 1918 | 2291 | 1514 | 164 | 622 | 1057 | 1652 | 638 | 3835 | 111 | 18 | 5 | 3135 | 834 | 2756 | 1213 |

| P | 0.134 | 0.000 | 0.048 | 0.468 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||||||||||

Figure 1.

The percentage positivity of H. pylori infection and inflammatory activity in 3969 cases of atrophic gastritis according to age group.

3.1. H. pylori and Inflammatory Activity

There were 834 subjects (21.01%) with H. pylori infection; among these patients, 770 subjects (92.33%) had simultaneous inflammatory activity (Table 2). H. pylori positivity was 63.48% in patients with inflammatory activity, which was significantly higher than that of those without inflammatory activity (2.32%). Only 7.67% of H. pylori-infected patients were negative for inflammatory activity. H. pylori infection was significantly correlated with inflammatory activity (P ≤ 0.01; Table 3).

Table 2.

The distribution of inflammatory (neutrophil) activity, gastric atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, and dysplasia according to the presence or absence of H. pylori infection.

| H. pylori infection | Cases (N) | Gender | Inflammatory activity | Gastric atrophy | Intestinal metaplasia | Dysplasia | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Negative | Positive | Mild | Moderate | Severe | None | Mild | Moderate | Severe | None | Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||

| Negative (%) | 3135 | 1623 (51.77) | 1512 (48.23) | 2692 (85.87) | 443 (14.13) | 1818 (57.99) | 1174 (37.45) | 143 (4.56) | 466 (14.87) | 1988 (63.41) | 564 (17.99) | 117 (3.73) | 3022 (96.40) | 93 (2.97) | 15 (0.48) | 5 (0.15) |

| Positive (%) | 834 | 428 (51.32) | 406 (48.68) | 64 (7.67) | 770 (92.33) | 473 (56.71) | 340 (40.77) | 21 (2.52) | 156 (18.71) | 570 (68.34) | 74 (8.87) | 34 (4.08) | 813 (97.48) | 18 (2.16) | 3 (0.36) | 0 (0) |

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Total | 3969 | 2051 | 1918 | 2756 | 1213 | 2291 | 1514 | 164 | 622 | 2558 | 638 | 151 | 3835 | 111 | 18 | 5 |

| P | 0.817 | 0.000 | 0.013 | 0.000 | 0.368 | |||||||||||

Note. The numbers in parentheses represent the percentage of inflammatory activity, gastric atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, and dysplasia in the H. pylori-negative and -positive groups.

Table 3.

The distribution of H. pylori infection, gastric atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, and dysplasia according to the presence or absence of inflammatory activity.

| Inflammatory activity | Cases (N) | Gender | H. pylori infection | Gastric atrophy | Intestinal metaplasia | Dysplasia | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Negative | Positive | Mild | Moderate | Severe | None | Mild | Moderate | Severe | None | Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||

| Negative (%) | 2756 | 1399 (50.76) | 1357 (49.24) | 2692 (97.68) | 64 (2.32) | 1625 (58.96) | 1005 (36.47) | 126 (4.57) | 414 (15.02) | 1763 (63.97) | 476 (17.27) | 103 (3.74) | 2655 (96.34) | 85 (3.08) | 12 (0.44) | 4 (0.14) |

| Positive (%) | 1213 | 652 (53.75) | 561 (46.25) | 443 (36.52) | 770 (63.48) | 666 (54.91) | 509 (41.96) | 38 (3.13) | 208 (17.15) | 795 (65.54) | 162 (13.36) | 48 (3.95) | 1180 (97.28) | 26 (2.14) | 6 (0.50) | 1 (0.08) |

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Total | 3969 | 2051 | 1918 | 3135 | 834 | 2291 | 1514 | 164 | 622 | 2558 | 638 | 151 | 3835 | 111 | 18 | 5 |

| P | 0.083 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.020 | 0.381 | |||||||||||

Note. The numbers in parentheses represent the percentage of H. pylori infection, gastric atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, and dysplasia in the inflammatory activity-negative and -positive groups.

3.2. H. pylori and Precancerous Gastric Lesions

The percentage of H. pylori infection and inflammatory activity among 164 subjects with severe CAG was 12.80% and 23.17%, respectively, which was significantly lower than that of the mild (20.65% and 29.07%) and moderate (22.46% and 33.62%) CAG patients (Table 4).

Table 4.

The distribution of H. pylori infection, inflammatory (neutrophil) activity, intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia according to the grade of gastric atrophy.

| Gastric atrophy | Cases (N) | Gender | H. pylori infection | Inflammatory activity | Intestinal metaplasia | Dysplasia | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | ||

| Mild (%) | 2291 | 1144 | 1147 | 1818 | 473 (20.65) | 1625 | 666 (29.07) | 496 | 1795 (78.35) | 2230 | 61 (2.66) |

| Moderate (%) | 1514 | 821 | 693 | 1174 | 340 (22.46) | 1005 | 509 (33.62) | 117 | 1397 (92.27) | 1453 | 61 (4.03) |

| Severe (%) | 164 | 86 | 78 | 143 | 21 (12.80) | 126 | 38 (23.17) | 9 | 155 (94.51) | 152 | 12 (7.32) |

|

| |||||||||||

| Total (%) | 3969 | 2051 | 1918 | 3135 | 834 (21.01) | 2756 | 1213 (30.56) | 622 | 3347 (84.33) | 3835 | 134 (3.38) |

| P | 0.034 | 0.013 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||||

Note. The numbers in parentheses represent the percentage of H. pylori infection, inflammatory activity, intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia in patients with different degrees of gastric atrophy.

The H. pylori positivity rate in the CAG patients with IM was 20.26%, which was significantly lower than those without IM (25.08%; P ≤ 0.05) (Table 5). The H. pylori positivity was not significantly different between the CAG patients with ED and those without ED (Table 6).

Table 5.

The distribution of H. pylori infection, inflammatory (neutrophil) activity, gastric atrophy, and dysplasia according to the presence or absence of intestinal metaplasia.

| Intestinal metaplasia | Cases (N) | Gender | H. pylori infection | Inflammatory activity | Gastric atrophy | Dysplasia | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Negative | Positive | ||

| Negative (%) | 622 | 271 | 351 | 466 | 156 (25.08) | 414 | 208 (33.44) | 496 (79.74) | 117 (18.81) | 9 (1.45) | 606 | 16 (2.57) |

| Positive (%) | 3347 | 1780 | 1567 | 2669 | 678 (20.26) | 2342 | 1005 (30.03) | 1795 (53.63) | 1397 (41.74) | 155 (4.63) | 3229 | 118 (3.53) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Total (%) | 3969 | 2051 | 1918 | 3135 | 834 (21.01) | 2756 | 1213 (30.56) | 2291 (57.72) | 1514 (38.15) | 164 (4.13) | 3835 | 134 (3.38) |

| P | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.02 | 0.000 | 0.513 | |||||||

Note. The numbers in parentheses represent the percentage of H. pylori infection, inflammatory activity, gastric atrophy, and dysplasia in the intestinal metaplasia-negative and -positive groups.

Table 6.

The distribution of H. pylori infection, inflammatory (neutrophil) activity, gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia according to the presence or absence of dysplasia.

| Dysplasia | Cases (N) | Gender | H. pylori infection | Inflammatory activity | Gastric atrophy | Intestinal metaplasia | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Negative | Positive | ||

| Negative (%) | 3835 | 1966 | 1869 | 3022 | 813 (21.20) | 2655 | 1180 (30.77) | 2230 (58.15) | 1453 (37.89) | 152 (3.96) | 606 | 3229 (84.2) |

| Positive (%) | 134 | 85 | 49 | 113 | 21 (15.67) | 101 | 33 (24.63) | 61 (45.52) | 61 (45.52) | 12 (8.96) | 16 | 118 (88.06) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Total (%) | 3969 | 2051 | 1918 | 3135 | 834 (21.01) | 2756 | 1213 (30.56) | 2291 (57.72) | 1514 (38.15) | 164 (4.13) | 622 | 3347 (84.33) |

| P | 0.031 | 0.368 | 0.381 | 0.000 | 0.513 | |||||||

Note. The numbers in parentheses represent the percentage of H. pylori infection, inflammatory activity, gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia in the dysplasia-negative and -positive groups.

3.3. Gastric Atrophy, Intestinal Metaplasia and Epithelial Dysplasia

IM was present in 84.33% and ED was present in 3.38% of patients with CAG. The IM and ED notably increased in positive association with more severe grade of gastric atrophy (Table 4). IM and ED appeared not to correlate with each other (Tables 5 and 6).

4. Discussion

H. pylori colonizes the stomach of more than half of the world's population, and this infection continues to play a key role in the pathogenesis of a number of gastroduodenal diseases [5]. It is hence classified as a Group A carcinogen by the World Health Organization. Epidemiological studies have determined that the attributable risk of gastric cancer conferred by H. pylori infection is approximately 75% [6]. Although evidence is emerging that the prevalence of H. pylori is declining in all age groups, the understanding of its disease spectrum continues to evolve [7].

Our study compared the H. pylori infection and gastric precancerous conditions in CAG by histological examination. We analyzed the presence of H. pylori infection in patients of different ages and found that the incidence of H. pylori infection decreased with age. However, several studies showed that the prevalence of H. pylori infection increased with age in general population in developing and developed countries [8–10], and few studies focused on H. pylori infection and age in atrophic patients. We also found that 92.33% of the H. pylori-positive patients had simultaneous inflammatory activity, which demonstrated a statistically significant relationship between H. pylori infection and neutrophil activation. These results are consistent with those of Khulusi et al. [11], as H. pylori infection could result in neutrophil activation and chronic gastritis [12].

Loss of normal glandular tissue is the first specific recognizable step in the precancerous cascade of gastric carcinoma [13]. Chronic H. pylori-induced inflammation can eventually lead to the loss of the normal gastric mucosal architecture, with destruction of the gastric glands and replacement by fibrosis and intestinal-type epithelium. This process of CAG and IM occurs in approximately half of the H. pylori-colonized population at sites in which inflammation is most severe [14]. The risk of CAG development depends on the distribution and pattern of chronic active inflammation.

Our study showed a low prevalence (21.01%) of H. pylori infection in all of the antral CAG patients, and the positivity rate decreased with growing severity of gastric atrophy. H. pylori infection is an established risk factor for CAG. Weck et al. reported that the odds ratio for the association between CAG and H. pylori infection alone was 2.9 (95% confidence interval: 2.3−3.6) [15]. What caused the low prevalence of H. pylori infection in the CAG patients in our study, particularly in those with severe atrophy? H. pylori colonization of the gastric mucosa may persist for decades or for life, unless it is eradicated by antimicrobial treatment. Perhaps the clearance of H. pylori infection in advanced stages of the disease is responsible for this finding. Alternatively, there is some evidence that the prevalence of these infections is declining in countries that have been rapidly developing economically, resulting from an associated improvement in the standard of living [16].

IM represents a phenotypic change from that of the normal epithelial cells of the gastric mucosa to an intestinal phenotype. It is considered to be an advanced stage of atrophy because the original glands, are replaced by metaplastic glands and chronologically, the metaplastic glands appear after the gastric glands are lost. In the present study, the majority of the CAG patients presented with IM. Furthermore, IM correlated significantly with the severity of CAG. ED is characterized by a neoplastic phenotype, both in terms of cell morphology and architectural organization. In the current study, the prevalence of ED increased with the progression of CAG. Evolution into gastric cancer was documented for all grades of dysplasia and correlated significantly with severe CAG [17].

Taken together, this study has shown that the incidence of H. pylori infection decreased with age and correlated significantly with inflammatory activity in CAG patients. IM and ED positivity notably increased as the degree of gastric atrophy increased. Although significant findings were revealed in the present analysis of the clinical and pathological characteristics of 3969 CAG cases, there were some limitations to our study. Only a histological examination of H. pylori infection was performed, which may have decreased the H. pylori detection rate. Further large population-based prospective studies are needed to better understand the progression of CAG.

Authors' Contribution

Lixiong Ying and Shaohua Chen contributed equally to this work.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Traditional Chinese Medicine Program of Zhejiang Province China (no. 2010ZA053) and the Medicine & Health Program of Zhejiang Province China (no. 2011RCB019). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the paper. The authors have no conflict of interests to disclose.

Abbreviations

- H. pylori:

Helicobacter pylori

- CAG:

Chronic atrophic gastritis

- IM:

Intestinal metaplasia

- ED:

Epithelial dysplasia.

References

- 1.McColl KE. Helicobacter pylori infection. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;362(17):1597–1604. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1001110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polk DB, Peek RM., Jr. Helicobacter pylori: gastric cancer and beyond. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2010;10(6):403–414. doi: 10.1038/nrc2857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haziri A, Juniku-Shkololli A, Gashi Z, Berisha D, Haziri A. Helicobacter pylori infection and precancerous lesions of the stomach. Medicinski Arhiv. 2010;64(4):248–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney System. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 1996;20(10):1161–1181. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199610000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kandulski A, Selgrad M, Malfertheiner P. Helicobacter pylori infection: a clinical overview. Digestive and Liver Disease. 2008;40(8):619–626. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2008.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herrera V, Parsonnet J. Helicobacter pylori and gastric adenocarcinoma. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2009;15(11):971–976. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pacifico L, Anania C, Osborn JF, Ferraro F, Chiesa C. Consequences of Helicobacter pylori infection in children. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2010;16(41):5181–5194. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i41.5181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Logan RP, Walker MM. ABC of the upper gastrointestinal tract: epidemiology and diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. British Medical Journal. 2001;323(7318):920–922. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7318.920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Zanten SJV, Pollak PT, Best LM, Bezanson GS, Marrie T. Increasing prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection with age: continuous risk of infection in adults rather than cohort effect. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1994;169(2):434–437. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.2.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruden DL, Bruce MG, Miernyk KM, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of tests for Helicobacter pylori in an Alaska Native population. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2011;17(42):4682–4688. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i42.4682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khulusi S, Mendall MA, Patel P, Levy J, Badve S, Northfield TC. Helicobacter pylori infection density and gastric inflammation in duodenal ulcer and non-ulcer subjects. Gut. 1995;37(3):319–324. doi: 10.1136/gut.37.3.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanko MN, Manasseh AN, Echejoh GO, et al. Relation between Helicobacter pylori, inflammatory (neutrophil) activity, chronic gastritis, gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice. 2008;11(3):270–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Correa P, Piazuelo MB. The gastric precancerous cascade. Journal of Digestive Diseases. 2012;13(1):2–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2011.00550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuipers EJ, Uyterlinde AM, Pena AS, et al. Long-term sequelae of Helicobacter pylori gastritis. The Lancet. 1995;345(8964):1525–1528. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91084-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weck MN, Gao L, Brenner H. Helicobacter pylori infection and chronic atrophic gastritis: associations according to severity of disease. Epidemiology. 2009;20(4):569–574. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181a3d5f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fock KM, Katelaris P, Sugano K, et al. Second Asia-Pacific consensus guidelines for Helicobacter pylori infection. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2009;24(10):1587–1600. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rugge M, Farinati F, Baffa R, et al. Gastric epithelial dysplasia in the natural history of gastric cancer: a multicenter prospective follow-up study. Gastroenterology. 1994;107(5):1288–1296. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90529-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]