Abstract

An Fe diphosphineborane platform that was previously reported to facilitate a high degree of N2 functionalization is herein shown to effect reductive CO coupling. Disilylation of an Fe dicarbonyl precursor furnishes a structurally unprecedented Fe dicarbyne complex. Several complexes related to this process are also characterized which allows for a comparative analysis of their respective Fe–B and Fe–C bonding. Facile hydrogenation of the Fe dicarbyne at ambient temperature and 1 atm H2 results in release of a CO-derived olefin.

Reductive coupling of CO to C2+-containing products has been a longstanding focus in organometallic chemistry primarily motivated by the goal of developing homogeneous alternatives to Fischer-Tropsch reactions.1 In addition, it was recently discovered that nitrogenases, best known for effecting N2 reduction to NH3, also reduce CO to higher-order hydrocarbons.2 As such, studies of metal complexes that mediate reductive CO coupling remain of high interest in the dual contexts of improving syngas conversion technologies as well as modeling biological carbon fixation.

One approach to C–C bond formation from CO-derived ligands is coupling of two carbynes at a single metal site.3 To this end, Lippard and coworkers previously described the disilylation of Na[(dmpe)2M(CO)2] (M = V, Nb, or Ta; dmpe = Me2PCH2CH2PMe2) complexes to form CO-derived η2-alkyne ligands4 which can undergo subsequent hydrogenation to release an olefin.4c, 5 Although dicarbyne6 intermediates were proposed in these reactions,7 such species were not detected. Similarly, Mayr and coworkers reported the transformation of W(CO)6 to a nucleophilic cis-acyl-carbyne complex which, upon further elaboration of the acyl group, undergoes C–C coupling to form an η2-alkyne ligand;8 a W dicarbyne intermediate was proposed but not observed. In the related context of isocyanide reductive coupling, Filippou and Pombeiro have studied the synthesis9 and C–C coupling reactivity9a–c of bis(aminocarbyne) Mo and W complexes. In this report, we describe the preparation of an unprecedented mononuclear Fe dicarbyne complex that is derived from CO. Structural, spectroscopic, and theoretical characterization of the Fe dicarbyne as well as several related species permits a comparative analysis of the bonding in these highly covalent complexes. Moreover, exposure of the featured dicarbyne to H2 (1 atm) results in the facile release of a Z-olefin product at room temperature (RT).

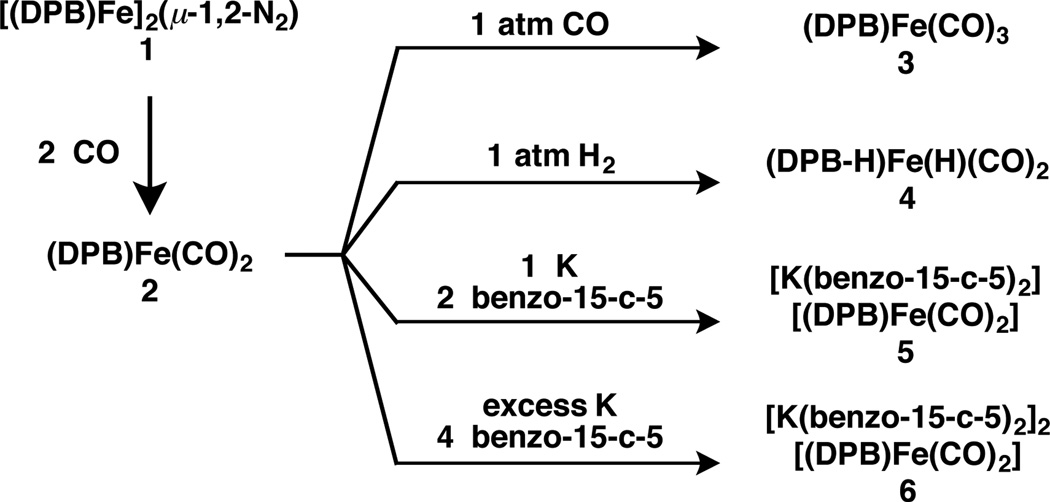

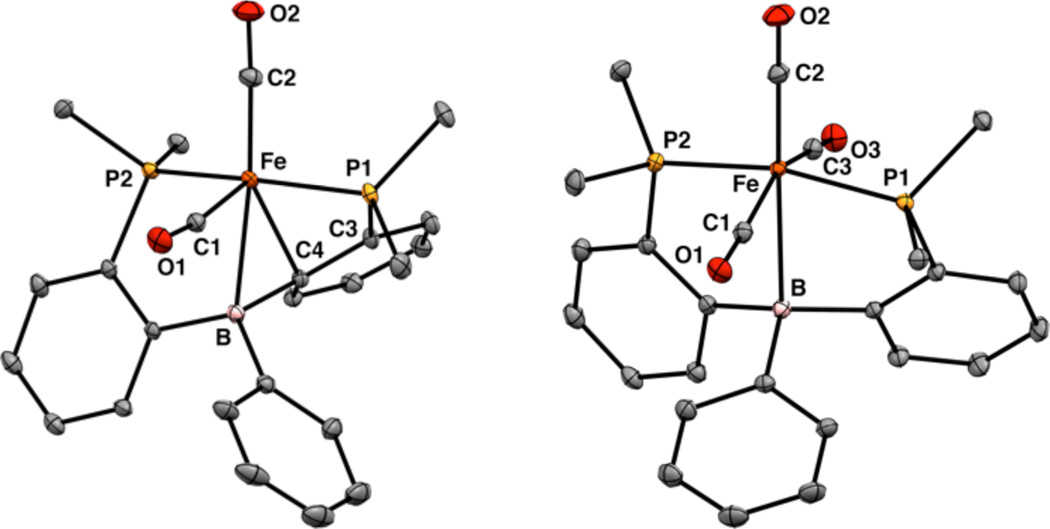

The CO reduction chemistry described herein utilizes the (DPB)Fe platform10 (DPB:11 PhB(o-iPr2PC6H4)2) which has been recently shown to facilitate a high degree of N2 functionalization. In Fe complexes of this ligand, the polyhaptic BPh moiety can function as a donor and/or an acceptor, thereby making this framework well suited for multi-electron, reductive transformations. For the purposes of CO coupling, we targeted (DPB)Fe complexes with >1 CO ligand. Addition of 1 atm CO to the previously described diiron bridging N2 complex10 1 results in initial formation of red-orange (DPB)Fe(CO)2 2 followed by paleyellow (DPB)Fe(CO)3 3 (Scheme 1). Prolonged photolysis of solutions of 3 results in loss of CO and regeneration of 2. This conversion is accompanied by binding of a phenylene linker in 2 (Figure 1) to give a geometrical motif similar to that observed in the isoelectronic complex (TPB)Fe(CO) (TPB: B((o-iPr2PC6H4)3).12 The asymmetry in the solid-state structure of 2 is maintained in solution as evidenced by the presence of two sharp peaks in its 31P NMR spectrum at 90.6 and 54.6 ppm (2JPP = 65.3Hz). Given previous work with Fe and Ni complexes of this ligand class,10, 13 we anticipated that the η3-BCC interaction in 2 could be hemilabile and participate in an E–H bond activation process. Accordingly, colorless (DPB–H)Fe(H)(CO)2 4 is formed quantitatively over the course of minutes upon exposure of 2 to 1 atm H2 at RT. Its 1H NMR spectrum shows the presence of a terminal Fe–H signal at −7.73 ppm (1H, dt, 2JHP = 54.4 Hz, 2JHH = 7.6 Hz) and a bridging Fe–H–B signal at −17.0 ppm (1H, br); XRD analysis establishes its cis-dihydride stereochemistry (see SI).

Scheme 1.

Figure 1.

Displacement ellipsoid (50%) representations of (left) 2 and (right) 3. PiPr2 groups are truncated and H atoms are omitted for clarity.

Complex 2 exhibits two quasireversible waves in its cyclic voltammagram at −1.94 and −2.70 V vs. Fc/Fc+ (see SI), prompting us to pursue one- and two-electron chemical reductions.14 Accordingly, mono- and dianions 5 and 6 were prepared by reduction with K and isolated with [K(benzo-15-crown-5)2] countercations. Structural characterization by XRD analysis shows that both 5 and 6 lack the phenylene interaction that is present in 2 (Figure 2). Monoanion 5 adopts a geometry between trigonal bipyramidal (TBP) and square pyramidal (τ = 0.44)15 with a wide ∠(P–Fe–P) = 142.71(2)° whereas dianion 6 is TBP (τ = 0.93) with a contracted ∠(P–Fe–P) = 120.60(1)°. The wide ∠(P–Fe–P) in 5 suggests that the unpaired electron resides in an orbital in the P–Fe–P plane; both the rhombic X-band EPR signal and the calculated spin density of 5 support this assignment (see SI). The Fe–B distances in 5 and 6 are nearly equivalent at 2.4192(15) and 2.4099(9) Å, respectively, while the average Fe–P and Fe–C(O) distances contract upon reduction from 5 to 6 (Table 1). A marked decrease in νCO upon reduction of 2 to 5 and 5 to 6 is also observed (Table 1). Taken together, these data suggest that the extra electron density in 6 is absorbed largely by increased Fe–CO and Fe–P π backbonding rather than increased Fe–B σ backbonding.

Figure 2.

Displacement ellipsoid (50%) representations of (left) 5 and (right) 6. PiPr2 groups are truncated and H atoms, solvent molecules, and countercations are omitted for clarity.

Table 1.

Selected bond lengths (Å), angles (°), and IR bands (cm−1)

| Fe–CO (avg.) | Fe–P (avg.) | Fe–B | Σ∠(C–B–C) | νCO(sym,asym) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1.745 | 2.212 | 2.3080(15) | 342 | 1908, 1863 |

| 5 | 1.756 | 2.212 | 2.4192(15) | 330 | 1857, 1791 |

| 6 | 1.727 | 2.156 | 2.4099(9) | 330 | 1738, 1659 |

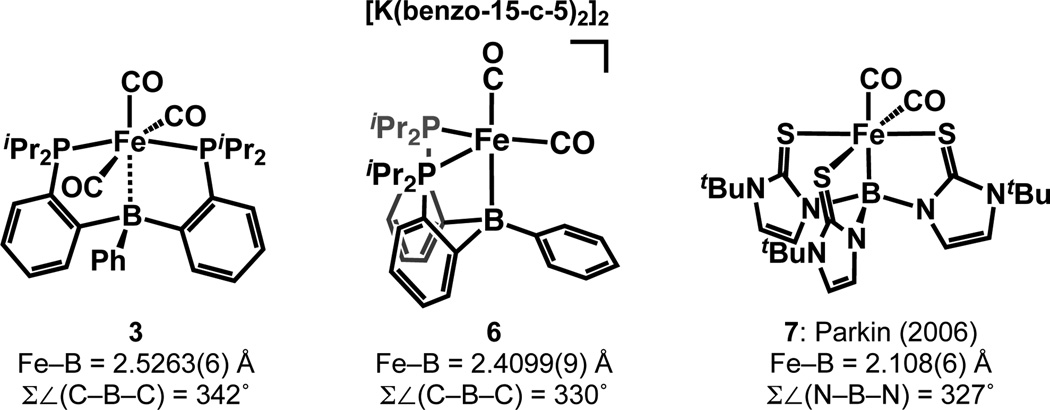

Complexes 3 and 6 as well as the first reported Fe–borane complex, (κ4-B(mimtBu)3)Fe(CO)2 7 (mimtBu = 2-mercapto-1-tert-butylimidazolyl),16 are all 18-electron Fe polycarbonyl complexes, and therefore constitute an informative set for comparison of their Fe–B bonding (Chart 1). Compared with 6, complex 3 has a longer Fe–B distance (2.5263(6) vs. 2.4099(9) Å), a less pyramidalized B center (Σ∠(C–B–C)) = 342° vs. 330°), and a less upfield-shifted 11B NMR signal (20.3 vs. 14.1 ppm). These data indicate somewhat stronger Fe–B bonding in 6 compared with 3, which may be rationalized by the dianionic charge and more electron-releasing Fe center in the former.

Chart 1.

Selected Fe–BR3 complexes.

Both 3 and 7 are nominally isoelectronic ML5Z complexes17 and their Fe centers could therefore be considered divalent (assuming strong Fe–B bonding) or zero-valent (assuming weak Fe–B bonding).18 The most striking contrast between 3 and 7 is that the Fe–B distance in 7 is 2.108(6) Å—ca. 0.4 Å shorter than that in 3. We attribute this difference primarily to the greater Lewis acidity of the B center of 7 (though the relative electron richness of the Fe centers may also be a contributing factor). Whereas the B atom in 3 has three C substituents and conjugates into the π system of the phenyl group, the B atom in 7 has three electronegative N substituents that contribute little π donation owing to the orthogonal orientation of the pyrrolyl groups with respect to the B 2pz orbital. The Lewis acidity of the B atom in 7 is therefore expected to be much greater than that of the B atom in 3. Accordingly, while the Fe center in 7 may be formulated as divalent, the Fe center in 3 is in our view more usefully considered zero-valent, akin to that of Fe(CO)5.

Interestingly, the C–O stretching frequencies of 6 are reminiscent of some low-energy bands that have been observed for nitrogenases in the presence of CO (between 1679 and 1715 cm−1)19 which have been assigned to one or more formyl and/or bridging carbonyl ligand(s). The similarly low-energy bands in 6 demonstrate that highly charged, reduced complexes featuring terminal CO ligands may also give rise to such signals.

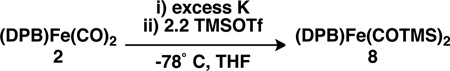

In addition, the low-energy CO stretches in 6 suggest the possibility that the O atoms may be functionalized with an electrophilic reagent.20 In situ reduction of 2 with excess K and addition to a −78 °C solution of 2.2 equiv trimethylsilyltriflate (TMSOTf) results in silylation of both O atoms to give the dicarbyne 8 (eq. 1). Since only two terminal Fe carbynes have been reported20b, 21 and 8 is a unique example of an Fe dicarbyne, its molecular and electronic structures are of particular interest. Although 8 reverts to 2 in solution over several days, the rate of this decomposition is sufficiently slow to allow for solid- and solution-state characterization.

|

(1) |

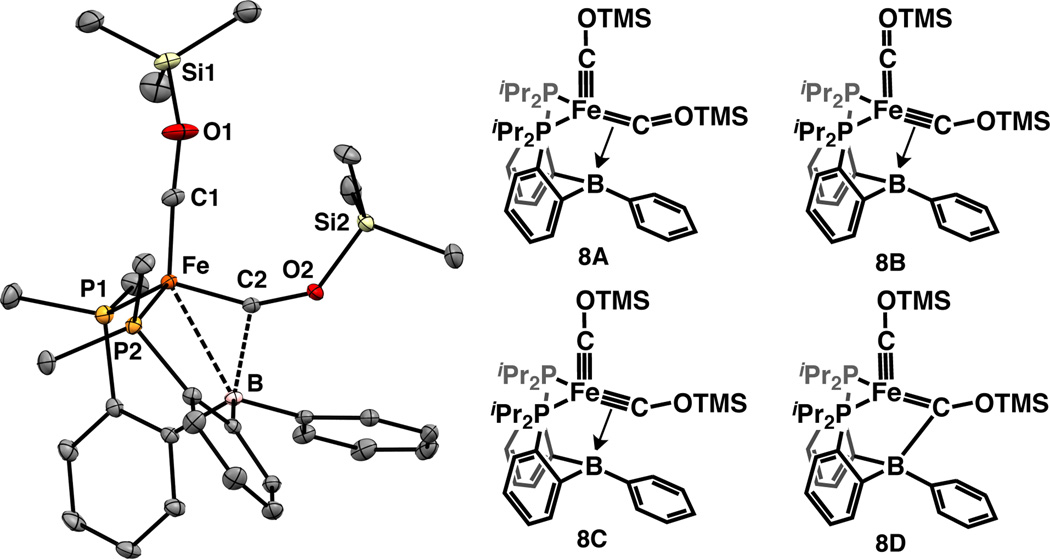

Single crystals of 8 contain two molecules in the asymmetric unit and were studied by XRD analysis (Figure 3). The very short Fe–C distances of 1.639 Å (Fe–C1 avg.) and 1.676 Å (Fe–C2 avg.) are similar to the Fe–C distance of 1.671(2) Å reported for (SiP3)Fe(COTMS)20b (SiP3: (o-iPr2PC6H4)3Si) and indicate Fe–C multiple-bond character for both carbyne ligands. The C2 carbyne ligand is distinguished by a long, yet non-negligible B–C2 interaction (1.86 Å (avg.)) and a contracted ∠(Fe–C2–O2) of 151° (avg.), compared with 171° (avg.) for ∠(Fe–C1–O1). In solution, the two carbyne ligands in 13C-labeled samples are further differentiated by their 13C NMR resonances at 230.2 ppm (d, 2JCC = 3.2 Hz) and 261.9 ppm (dt, 2JCP = 9.0 Hz, 2JCC = 3.2 Hz), assigned to C1 and C2, respectively, on the basis of DFT calculations (see SI). For reference, the chemical shift corresponding to the carbyne ligand in (SiP3)Fe(13COTMS) is 250.3 ppm (q, 2JCP = 16.4 Hz).22 The B atom in 8 is pyramidalized in both the solution and solid states as indicated by the low Σ∠(C–B–C) = 328° (avg.) and upfield-shifted 11B NMR signal (6.4 ppm). In addition, the Mössbauer isomer shift of 8 (δ = −0.200 mm s−1) is substantially more negative than that of 2 (δ = 0.087 mm s−1), indicating a greater degree of Fe–L covalent bonding in 8 (see SI). Taken together, these XRD, NMR, and Mössbauer data suggest that extensive Fe–C multiple bonding and additional C2–B bonding should be considered when assessing the valence bonding in 8.

Figure 3.

Displacement ellipsoid (50%) representation of one of the two crystallographically-independent molecules of 8 (left). PR2 groups are truncated. Relevant resonance structures of 8 (right).

To account for these features, we propose several possible resonance structures for 8 (Figure 3). Structures 8A, 8B, and 8C have two dicarbyne ligands, one of which exhibits dative bonding to the pendant borane. Structures 8A and 8B emphasize that a dblock metal does not have enough orbitals to form four independent π bonds (as in 8C);3a, 9d however, 8C may be a valid resonance contributor if either three-center hyperbonding23 or mixing with Fe 4p orbitals24 is invoked. Resonance form 8D is distinguished from 8A/B/C in that the B atom in 8D is bonded to one of the carbynes by a two-center “normal” covalent bond,25 thereby rendering that fragment a zwitterionic Fischer-type carbene with a formal negative charge on the B atom. The Fe– C(OR)–B bonding in 8 may be compared to the M–C(R)–H bonding in α-agostic alkylidenes:26 analogously to 8, the latter class of compounds is characterized by M–C–R angles between 120° and 180°, short M–C distances, and long C–H distances. Whereas α-agostic alkylidenes feature attenuated—but significant—1JCH values,26 no 11B–13C coupling is resolved in the 13C signal corresponding to C2, suggesting that 1JBC is low (< 2 Hz, compared with 1JBC = 49.5 Hz for NaBPh4).27 Structurally, a boratocarbene ligand as depicted in 8D would be expected to display four B–C bonds of similar length since each C substituent would have sp2 hybridization; however, the B–C2 distance is ~0.2 Å (avg.) longer than the other B–Csp2 distances (1.65 Å (avg.)). In addition, the average Fe–C distance of all structurally-characterized O-substituted Fischer-type Fe carbenes is 1.90 Å,28 which is >0.2 Å (avg.) longer than the Fe–C2 distance observed in 8. Given the low value of 1JBC2 and these structural metrics, we weight resonance contributors 8A/B/C more heavily than 8D.

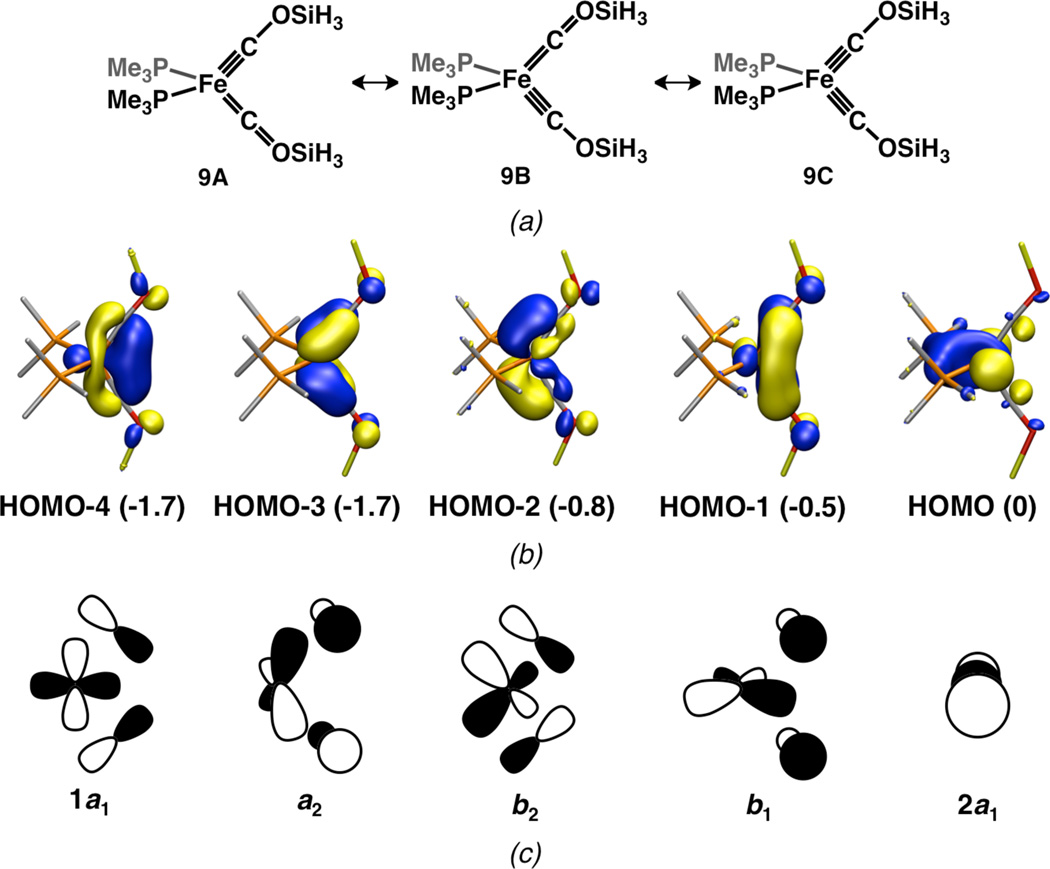

In order to gain further insight into the bonding in 8, the structures of 8 and a hypothetical, simplified model, (PMe3)2Fe(COSiH3)2 9 were optimized and studied using DFT (M06L/6−311+g(d)). The five highest-filled MOs of 9 (Figure 4) include one essentially non-bonding orbital with some degree of Fe–P backbonding (HOMO) as well as four highly covalent orbitals with significant Fe–C π bonding (HOMO-1 through HOMO-4). Thus, 9 may be regarded as isoelectronic to known compounds of the form (PR3)2Fe(NO)2.29 Although the filled MOs of 8 are more complex than those of 9 owing to the lower overall symmetry of 8 as well as mixing with aryl π orbitals, the shapes and ordering of the valence orbitals for the two molecules correlate with good fidelity (see SI). These calculations suggest that the electronic structures of 8 and 9 are largely analogous and that the electronic structure of 8, which includes the additional borane–carbyne interaction, may be considered as a perturbation of that of 9.

Figure 4.

(a) Resonance structures of 9; (b) calculated valence MOs of 9; (c) atomic orbital representations of the calculated MOs. Orbital energies (relative to the HOMO) are given in parentheses and isosurfaces are shown at the 0.05 e− Å−3 level.

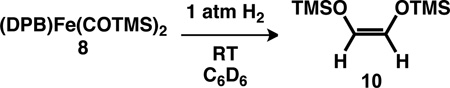

The stability of the dicarbyne form of 8 with respect to C–C coupling is in marked contrast to the analogous [(dmpe)2M(η2-(TMSO)C≡C(OTMS))]+ complexes (M = V, Nb, and Ta) which feature C–C-coupled η2-alkyne ligands (vide supra).4 Nevertheless, facile C–C coupling is achieved upon RT addition of 1 atm H2 to solutions of 8, which results in liberation of olefin 10 in moderate yield (43%, avg. of three runs; eq. 2). The hydrogenation of 8 is highly stereoselective, furnishing Z-olefin 10 without any detected E isomer. Performing the hydrogenation with a mixture of 12C- and 13C-labeled 8 gives only 12C12C and 13C13C olefin with no 12C13C olefin, which indicates that the C–C coupling process occurs at a single metal site. Although we have not yet been able to fully characterize the resulting Fe-containing product, there appears to be only one Fe-containing species, which is a paramagnet as indicated by 1H NMR spectroscopy. Previous examples of reductive CO coupling using Fe are few,30 and, to our knowledge, the release of an olefin by a hydrogenative CO reductive coupling pathway has not been previously reported for Fe. The aforementioned hydrogenation of [(dmpe)2M(η2-(TMSO)C≡C(OTMS))]+ complexes to release 10 occurs either at elevated H2 pressures (~8 atm H2 for M = V)4c or with the aid of a hydrogenation catalyst (1 atm H2 and 5% Pd/C for M = Ta).5 By comparison, hydrogenation of 8 occurs within minutes at 1 atm H2.

|

(2) |

In summary, we have shown that the (DPB)Fe platform, which was previously studied in the context of N2 functionalization,10 also facilitates CO functionalization to furnish a structurally unique Fe dicarbyne complex. Like the Fe aminoimide intermediate in (DPB)Fe-mediated N2 functionalization, the Fe dicarbyne complex in this report features extensive Fe–L multiple bonding. Initial reactivity studies of this species reveal that it undergoes hydrogenative C–C coupling to furnish a CO-derived olefin. Ongoing studies to map additional details regarding the release of 10 from 8 and to develop conditions for catalytic reductive CO coupling are underway.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We acknowledge the NIH (GM070757) and the Beckman Institute for funding and thank Lawrence Henling for assistance with XRD studies.

Funding Sources

No competing financial interests have been declared.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information. Experimental and computational details, spectra, and XRD tables. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.West NM, Miller AJM, Labinger JA, Bercaw JE. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2011;255:881–898. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Lee CC, Hu Y, Ribbe MW. Science. 2010;329:642–642. doi: 10.1126/science.1191455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yang ZY, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:19417–19421. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.229344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hu Y, Lee CC, Ribbe MW. Science. 2011;333:753–755. doi: 10.1126/science.1206883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Wilker CN, Hoffmann R, Eisenstein O. Nouv. J. Chim. 1983;7:585. [Google Scholar]; (b) Mayr A, Bastos CM. Prog. Inorg. Chem. 1992;40:1–98. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Bianconi PA, Williams ID, Engeler MP, Lippard SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986;108:311–313. [Google Scholar]; (b) Bianconi PA, Vrtis RN, Rao CP, Williams ID, Engeler MP, Lippard SJ. Organometallics. 1987;6:1968–1977. [Google Scholar]; (c) Protasiewicz JD, Lippard SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;22:6564–6570. [Google Scholar]; (d) Carnahan EM, Protasiewicz JD, Lippard SJ. Acc. Chem. Res. 1993;26:90–97. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vrtis RN, Bott SG, Rardin RL, Lippard SJ. Organometallics. 1991;10:1364–1373. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dicarbyne complexes have also been referred to as "carbene-carbyne" or "bis-carbene" complexes to reflect the fact that d-block metals do not have enough orbitals to form four independent π bonds. However, since the carbon centers in "•••CR" ligands are monovalent, we refer to these ligands as carbynes and the species in question as dicarbyne complexes. In addition to being consistent with current IUPAC definitions, this allows for carbene ligands (which have divalent carbon centers) to be distinguished from carbyne ligands. Nevertheless, it should be emphasized that the Fe dicarbyne complex in this report is a unique structure regardless of how many independent Fe–C π bonds it contains. See McNaught AD, Wilkinson A, editors. IUPAC Compendium of Chemical Terminology. 2nd Ed. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1997. Compiled by.

- 7.(a) Protasiewicz JD, Masschelein A, Lippard SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:808–810. [Google Scholar]; (b) Protasiewicz JD, Bronk BS, Masschelein A, Lippard SJ. Organometallics. 1994;13:1300–1311. [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDermott GA, Mayr A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987;109:580–582. [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Filippou AC, Grünleitner W, Völkl C, Kiprof P. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1991;30:1167–1169. [Google Scholar]; (b) Filippou AC, Völkl C, Grünleitner W, Kiprof P. J. Organomet. Chem. 1992;434:201–223. [Google Scholar]; (c) Wang Y, Da Silva JJF, Pombeiro AJ, Pellinghelli MA, Tiripicchio A, Henderson RA, Richards RL. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1995:1183–1191. [Google Scholar]; (d) Filippou AC, Hofmann P, Kiprof P, Schmid HR, Wagner C. J. Organomet. Chem. 1993;459:233–247. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suess DLM, Peters JC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:4938–4941. doi: 10.1021/ja400836u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bontemps S, Gornitzka H, Bouhadir G, Miqueu K, Bourissou D. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:1611–1614. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moret M-E, Peters JC. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:2063–2067. doi: 10.1002/anie.201006918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harman WH, Peters JC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:5080–5082. doi: 10.1021/ja211419t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.A recent Fe(CO)2 charge series: Tondreau AM, Milsmann C, Lobkovsky E, Chirik PJ. Inorg. Chem. 2011;50:9888–9895. doi: 10.1021/ic200730k.

- 15.Addison AW, Rao TN, Reedijk J, van Rijn J, Verschoor GC. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1984:1349. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Figueroa JS, Melnick JG, Parkin G. Inorg. Chem. 2006;45:7056–7058. doi: 10.1021/ic061353n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green MLH. J. Organomet. Chem. 1995;500:127–148. [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Hill AF. Organometallics. 2006;25:4741–4743. [Google Scholar]; (b) Parkin G. Organometallics. 2006;25:4744–4747. [Google Scholar]; (c) Sircoglou M, Bontemps S, Mercy M, Saffon N, Takahashi M, Bouhadir G, Maron L, Bourissou D. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:8583–8586. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Suess DLM, Tsay C, Peters JC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:14158–14164. doi: 10.1021/ja305248f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Anderson JS, Moret M-E, Peters JC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:534–537. doi: 10.1021/ja307714m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Thorneley R, George SJ. Prokaryotic Nitrogen Fixation: A Model System for Analysis of a Biological Process. Wymondham, UK: Horizon Scientific Press; 2000. p. 81. [Google Scholar]; (b) Yan L, Dapper CH, George SJ, Wang H, Mitra D, Dong W, Newton WE, Cramer SP. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2011;2011:2064–2074. doi: 10.1002/ejic.201100029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Peters JC, Odom AL, Cummins CC. Chem. Commun. 1997:1995. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lee Y, Peters JC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:4438–4446. doi: 10.1021/ja109678y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fischer EO, Schneider J, Neugebauer D. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1984;23:820–821. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caution should be exercised when interpreting these 13C shifts since transition metal carbyne and carbene ligands can assume a wide range of chemical shift values.

- 23.Landis CR, Weinhold F. J. Comput. Chem. 2006;28:198–203. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moret M-E, Zhang L, Peters JC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:3792–3795. doi: 10.1021/ja4006578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haaland A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1989;28:992–1007. [Google Scholar]

- 26.(a) Schultz AJ, Williams JM, Schrock RR, Rupprecht GA, Fellmann JD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979;101:1593–1595. [Google Scholar]; (b) Schrock RR. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:145–180. doi: 10.1021/cr0103726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weigert FJ, Roberts JD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1969;91:4940–4941. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Data from a CSD search including the May 2013 update.

- 29.Harrison W, Trotter J. J. Chem. Soc. A. 1971:1542. [Google Scholar]

- 30.(a) Bennett MJ, Graham W, Smith RA, Stewart RP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973;95:1684–1686. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wong A, Atwood JD. J. Organomet. Chem. 1980;199:C9–C12. [Google Scholar]; (c) Okazaki M, Ohtani T, Inomata S, Tagaki N, Ogino H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:9135–9138. [Google Scholar]; (d) Sazama GT, Betley TA. Organometallics. 2011;30:4315–4319. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.