Abstract

Spinal motoneurons (MNs) amplify synaptic inputs by producing strong dendritic persistent inward currents (PICs), which allow the MN to generate the firing rates and forces necessary for normal behaviors. However, PICs prolong MN depolarization after the initial excitation is removed, tend to “wind-up” with repeated activation and are regulated by a diffuse neuromodulatory system that affects all motor pools. We have shown that PICs are very sensitive to reciprocal inhibition from Ia afferents of antagonist muscles and as a result PIC amplification is related to limb configuration. Because reciprocal inhibition is tightly focused, shared only between strict anatomical antagonists, this system opposes the diffuse effects of the descending neuromodulation that facilitates PICs. Because inhibition appears necessary for PIC control, we hypothesize that Ia inhibition interacts with Ia excitation in a “push–pull” fashion, in which a baseline of simultaneous excitation and inhibition allows depolarization to occur via both excitation and disinhibition (and vice versa for hyperpolarization). Push–pull control appears to mitigate the undesirable affects associated with the PIC while still taking full advantage of PIC amplification.

Keywords: PIC, neuromodulation, push–pull, motoneuron

Introduction

Neuromodulation of motoneurons (MNs) by the monoamines serotonin (5HT) and norepinephrine (NE) greatly influences the way MNs receive, process, and transform synaptic inputs into meaningful motor outputs. While ionotropic inputs mediate the fast EPSPs and IPSPs, neuromodulatory inputs work by regulating the overall excitability of MNs and serve as a gain control for ionotropic synaptic inputs.1 The G-protein coupled receptors associated with neuromodulators activate complex intracellular pathways that ultimately result in amplifying incoming signals. In the case of spinal MNs, this amplification occurs mainly through interactions between incoming synaptic inputs and voltage-activated channels present on the dendrites. Thus, dendrites are now realized to be active processors of synaptic inputs.2

However, in voltage clamp experiments performed on mammalian spinal MNs in anesthetized animals, neuromodulation is believed to be greatly attenuated.3 Such experiments have revealed much about the MN’s passive state electrical properties, but to understand fully normal MN behavior, neuromodulatory effects must also be considered. For example, summing all ionotropic synaptic inputs in the absence of neuromodulation results in less than 50% of the drive MNs need to produce maximum firing frequencies and muscle forces.4 The monoamines 5-HT and NE are the main neuromodulators of motoneuronal activity.5,6 It has been shown in the decerebrate animal that the areas of the brainstem from which the noradrenergic and serotonergic innervation of the spinal cord arise (i.e., the locus coeruleus and the medulary raphe nuclei) are released from the inhibitory effects of anesthetics, approximating the neuromodulatory state of an awake behaving subject. The decerebrate mammalian preparation is thus both important and unique in that it allows us to study the MN with its full complement of both ionotropic and neuromodulatory inputs intact.

Neuromodulators have many effects on the MN. They hyperpolarize spike threshold,7,8 depolarize the resting membrane potential, and reduce the AHP.9 Perhaps the most profound effect neuromodulators have on MNs is the generation of a persistent inward current.10,11 The G-protein pathways coupled to 5HT-2 and NE alpha-1 produce a depolarizing current, primarily via dendritic CaV 1.312 channels, which can amplify synaptic inputs by as much as fivefold.13,14 The large differences in firing rate evoked by synaptic inputs in the anesthetized versus unanesthetized decerebrate preparations can be accounted for by the amplification provided by PICs. The effect of monoamines on MNs is thus profound. In fact, even motor behaviors requiring small to moderate forces would be virtually impossible to achieve without substantial monoaminergic drive.

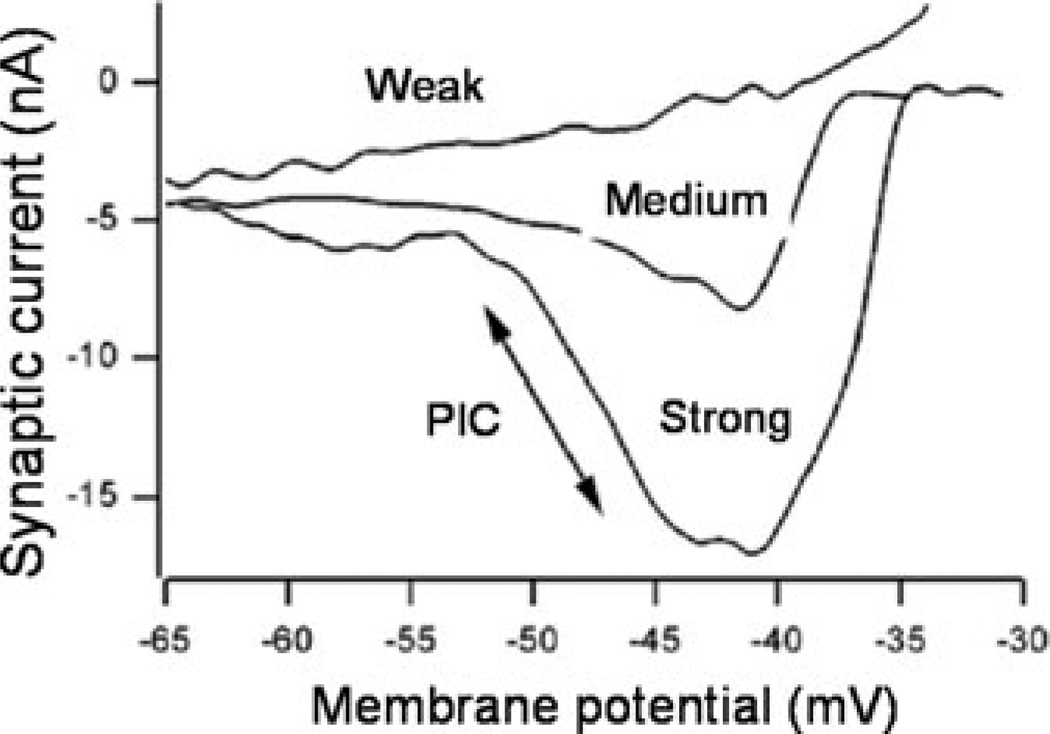

The amount of amplification of synaptic input is dependent on the amplitude of the PIC, which is proportional to the amount of neuromodulatory drive from the brainstem (Fig. 1).15 The output from the brainstem monoaminergic nuclei is not constant, but varies with different behaviors, is correlated with speed of locomotion,16 and state of arousal.17 Thus, neuromodulation, via the PIC, serves as a variable gain controller and has a truly transformative effect on MN behavior that provides a remarkable degree of flexibility for motor commands. Its presence is in fact an essential part of normal MN function.

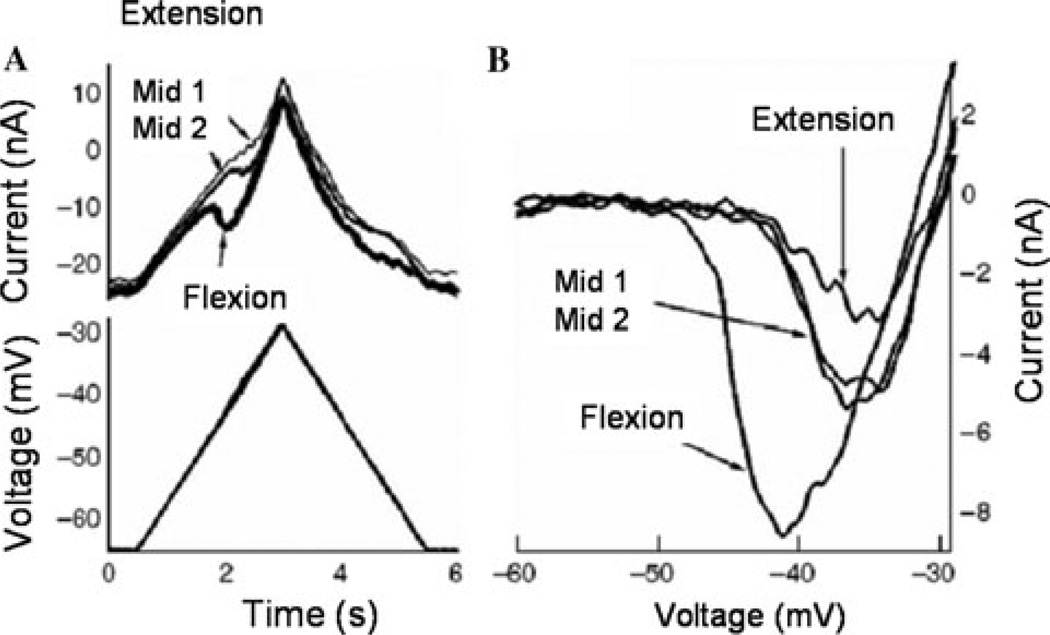

Figure 1.

The relative amount of neuromodulatory drive sets the potential amplitude of the PIC and hence the amount of synaptic amplification. With weak monoaminergic drive, the PIC amplitude is small; synaptic current decreases as the cell is depolarized. As monoaminergic drive increases to medium and then strong, a progressively larger PIC and greater amplification of synaptic currents results. Inward (depolarizing) currents are downward.

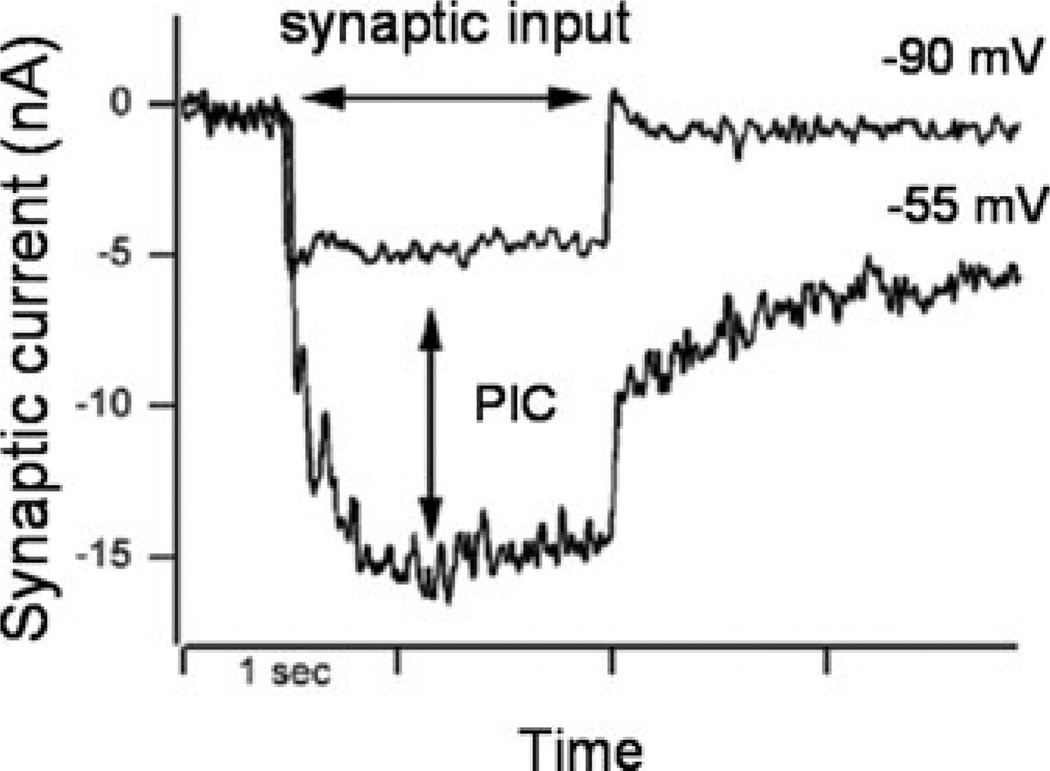

As critical as PICs are to the generation of normal motor outputs, they also present some potential problems. One of the initial effects that PICs were found to produce was bistability (Fig. 2).15 Cells with strong PICs tend to display plateau potentials in voltage clamp and prolonged firing in current clamp well after the cessation of excitatory input. Both can be terminated by a short pulse of inhibition.18,19 Although bistable behavior is probably essential for some normal behaviors, such as maintenance of posture,20–22 it is easy to see how prolongation of transient inputs would be undesirable for other motor tasks by possibly inducing errors during dynamic changes in motor commands and preventing MNs from accurately tracking any dynamically varying inputs. Another potential problem is the tendency for PICs to display “wind-up.” With repeated activation, PICs tend to progressively grow larger,23 especially in the absence of inhibition.24 This could cause undesirable, excessive, and uncontrolled motor output. PICs can also show quite a bit of variability in their activation, making them inconsistent amplifiers of synaptic input.25 In addition, the monoaminergic projections to the spinal cord are highly diffuse.26 They innervate many motor pools thus simultaneously spreading both the beneficial and undesirable effects of PICs and potentially locking joints or even an entire limb into prolonged states of high excitability.

Figure 2.

When the MN is held at a hyperpolarized level (top trace, −90 mV), a brief excitatory input results in a depolarizing synaptic current with a sharp onset and offset that lasts for the duration of the input. At a more depolarized level (bottom trace,−55mV), the same brief excitatory input results in an amplified depolarizing current that persists (tail current) after the excitation is removed. Both the amplification and prolongation can be attributed to the PIC. Baseline current removed.

Results

It is gradually becoming apparent that the nervous system has mechanisms in place to exploit the benefits of the PIC while minimizing these potential problems. Previous work in our lab, as well as others, has shown that the PIC is very sensitive to inhibition13,27 and that inhibition may be able to compensate for some of the problems associated with the PIC. In recordings from ankle extensor MNs in the decerebrate cat preparation, we have demonstrated that inhibition, in this case tonic inhibition from electrically stimulating nerves to antagonist muscles, reduces the magnitude of the PIC in a linear fashion.27 Although the interaction between the PIC and synaptic excitation is strong and results in a great deal of amplification of the synaptic input, excitatory inputs only serve to shift the activation threshold of the PIC and have no effect on its amplitude.

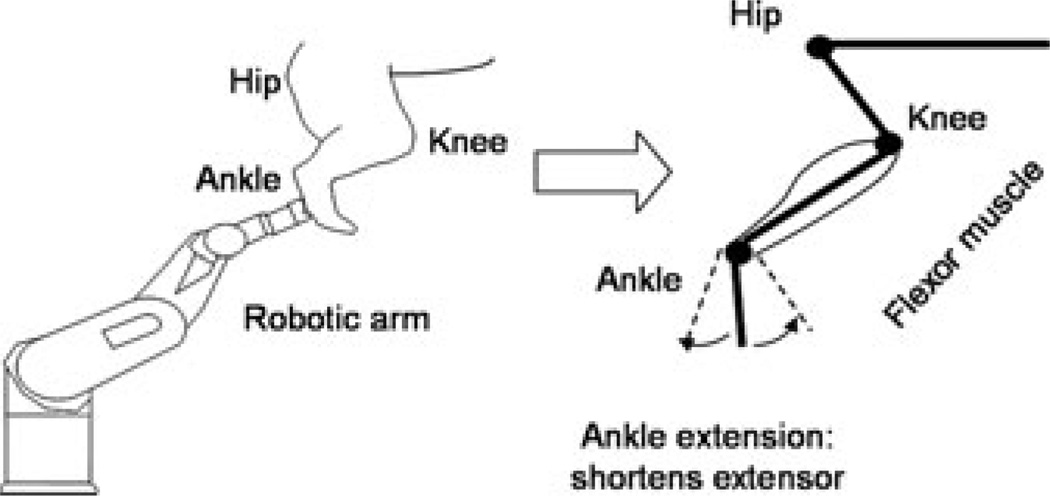

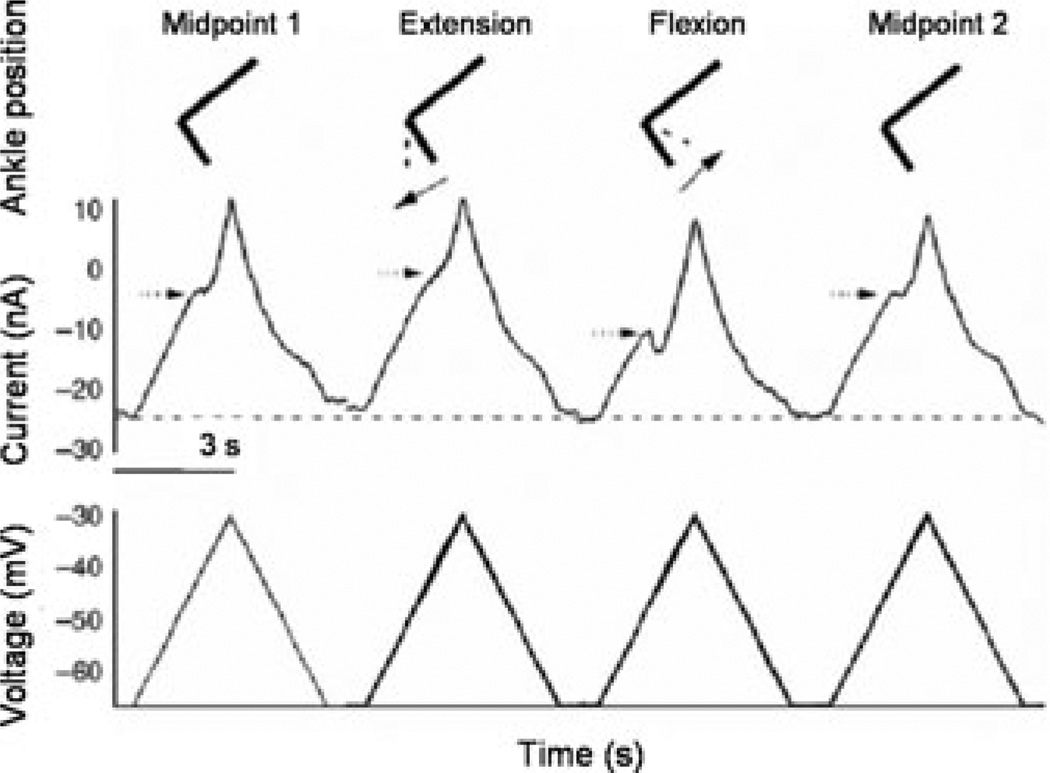

In other recent work in the decerebrate feline, we have shown how the Ia reciprocal inhibition system interacts with the PIC.24 In these experiments, the PIC amplitude and activation voltage were closely related to joint angle. We used a robotic arm and a paralyzed preparation to demonstrate that the PIC amplitude in ankle extensor MNs was extremely sensitive to joint position (Fig. 3). While triceps surae MNs were voltage clamped, the robot alternately held the ankle in a flexed and then extended position. Ankle extension shortens the triceps surae and lengthens the antagonist flexormuscles (tibialis anterior and extensor digitorum longus; TA/EDL). Ankle flexion has the opposite effect, stretching the triceps and shortening TA/EDL. The dendritic PIC was assessed by linearly increasing voltage ramps applied as the ankle was held steady at three different joint angles: midpoint (defined as the tibia at 90° with the bones of the foot), extended and flexed. We saw significant reduction in PIC amplitude with just 10° of extension of the ankle (Figs. 4 and 5).24 This further emphasizes the exquisite sensitivity of the PIC to inhibitory inputs, as small changes in the joint angle had a potent effect on the PIC amplitude. The source of inhibition is most likely from muscle spindle Ia afferents that generate reciprocal inhibition from the antagonist muscles, as denervation of cutaneous afferents did not alter this effect. The potent effect of joint angle probably occurs in dendritic regions of the cell, where the synaptic inputs interact with the PIC, because the voltage clamp prevented any changes in the behavior of somatic voltage-sensitive channels. Because the amplitude of the PIC determines the magnitude of synaptic amplification, active synaptic integration in MN dendrites depends on limb configuration.

Figure 3.

Experimental setup: A six degree-of-freedom robotic arm was used for passively rotating the ankle, knee, and hip joints.

Figure 4.

A voltage ramp applied to a tricep surae MN at ankle position midpoint 1 results in the presence of a PIC (arrow on current trace). When the same ramp is applied with the hindlimb in the extension position there is a reduction in PIC amplitude. This reduction is due to the interaction between reciprocal inhibition from antagonist muscles and the PIC. At the flexion position, PIC activation is shifted (hyperpolarized). Midpoint 2 conditions are identical to midpoint 1.

Figure 5.

(A) Single cell recording. The overlapping current traces demonstrate the differences in PIC amplitude at the different ankle positions. (B) Same cell as in A, following leak subtraction, with the ankle in the flexion position, synaptic amplification is greatest. At midpoints 1 and 2, the PIC amplitude is fairly similar and decreased from the flexion position. At the extension position, the PIC amplitude and synaptic amplification is smallest. Current traces are leak-subtracted.

As mentioned earlier, the neuromodulatory system of the brainstem/spinal cord is diffuse. Axons originating from the locus coeruleus and medullary raphe nuclei, the source of spinal NE and 5HT, innervate all segments and laminae of the entire spinal cord.28 This diffuse innervation has the potential to spread the benefits as well as the deficits associated with the PIC to all the motor pools. Recently, we studied how the focused nature of the Ia system interacts with the diffuse nature of descending neuromodulation. We used our robotic arm to impose movements about the various joints of the feline hindlimbwhile voltage clamping ankle extensor MNs. The robot imposed passive flexion and extension of the ankle, knee, and hip individually and then generated combined ankle, knee, and hip rotation to produce a whole limb movement. PIC amplification of sensory inputs associated with the rotations converging onto ankle extensor MNs was restricted to synaptic inputs coming from muscle pairs acting at the ankle joint and not to inputs from the knee or hip (Fig. 6).29 Studies involving electrical stimulation of muscle, cutaneous, and joint nerves have demonstrated polysynaptic pathways that cross multiple spinal segments. These contribute to whole limb coordination, especially in acutely spinalized preparations.30,31 Despite this, inputs from other muscles at other joints only produced weak synaptic currents in the ankle extensor MNs. After spinalization, not only was amplification via the PIC eliminated, but sensory inputs from other joints affected the ankle extensor MNs, effectively broadening their receptive field. The mechanism of this broadening is not clear, but presumably reflects the loss of descending inhibition of spinal circuits.

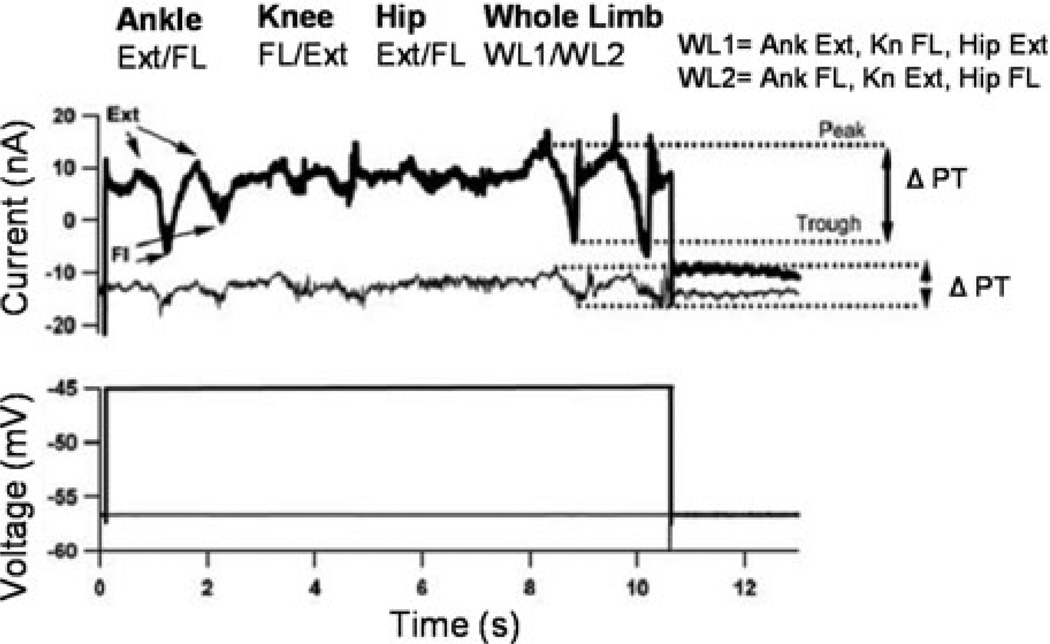

Figure 6.

Effective synaptic current in the tricep surae MN was recorded as the ankle, knee, and hip were flexed and extended individually and then in concert. The darker, thicker trace was a result of movements performed at a depolarized voltage, so that the PIC was activated. The thinner trace was a result of movements performed at a hyperpolarized voltage, below the threshold for activation of the PIC. In both voltage conditions it is apparent that the individual ankle and whole limb movements produce the largest amplitude compared to rotations of the knee or hip. This illustrates the focused nature of the cells receptive field.

Discussion

Both Ia monosynaptic excitation and Ia disynaptic reciprocal inhibition are tightly focused pathways.32 Because of the high sensitivity of the PIC amplitude to Ia reciprocal inhibition, it is likely that Ia reciprocal inhibition helps sculpt individual joint motions from a background of diffuse excitatory neuromodulation (Fig. 7). At present, we assume that this is an example of a diffuse neuromodulatory input interacting with a specific and local ionotropic input. How Ia reciprocal inhibition reduces PICs remains, however, to be fully explained.33,34 Although Ia reciprocal inhibition certainly involves ionotropic actions of the neurotransmitter glycine,35 it is possible that there may also be an inhibitory neuromodulatory component mediated through GABAb receptors as well.36

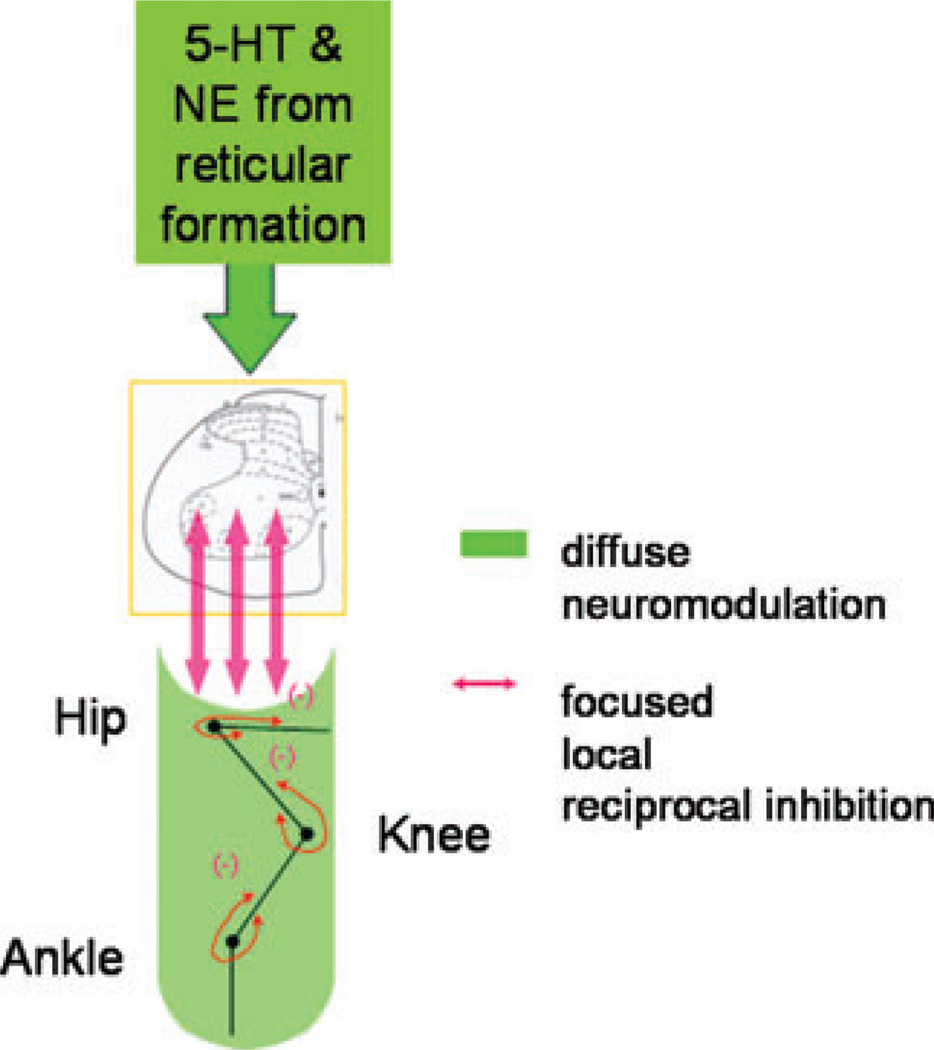

Figure 7.

The neuromodulatory inputs from the brainstem are diffuse involving all segments and laminae of the spinal cord. The Ia reciprocal inhibitory system is focused and helps “sculpt”movements out of a background of excitation.

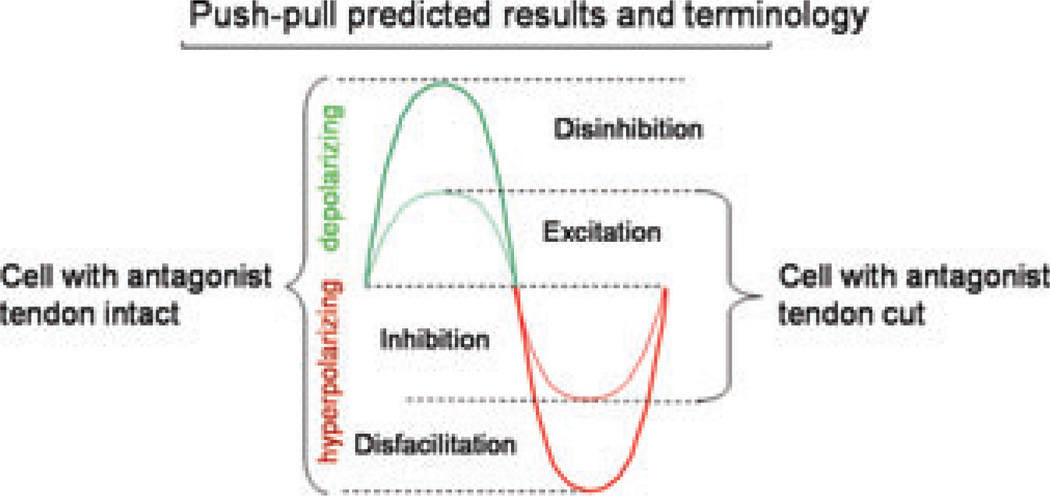

It seems likely that reciprocal inhibition from muscle stretch is particularly important for the transition from agonist to antagonist activation: as the agonist shortens it would receive reciprocal inhibition from the antagonist, whereas the antagonist reciprocal inhibition from the agonist would be reduced.24 Our premise here is that the inhibition needed for this compensation should be linked to excitation in a push–pull fashion. In this sense, push–pull control requires a steady background of excitation and inhibition and maximum MN depolarization is the result of disinhibition coupled with excitation instead of excitation alone. Similarly, hyperpolarization is the result of disfacilitation coupled with inhibition instead of inhibition alone (Fig. 8). One potential advantage of push– pull is that net input–output gain is increased because reciprocal changes in two inputs occur simultaneously, as suggested by recent studies in cortical neurons.37,38 Another potential advantage involves temporal dynamics. Although the tendency of the PIC to prolong excitatory inputs by inducing a plateau potential and self-sustained firing may be an advantage for posture, input prolongation could seriously distort inputs. An obvious example is locomotion, where prolongation of the stance phase by a PIC would be a substantial problem. Ia interneurons are rhythmically active during locomotion39,40 and thus the central pattern generator for locomotion may also be organized in a push–pull fashion. We are presently initiating studies of this question in our lab. A push–pull organization for excitation and inhibition would provide PIC deactivation during the inhibitory/disfacilitation phases and yet still allow strong PIC amplification during the excitatory/ disinhibition phases. Thus, push–pull might allow PIC amplification to be combined with accurate tracking of dynamic inputs.

Figure 8.

When tonic levels of excitation and inhibition are present maximum depolarization (and maximum firing frequencies) are achieved when disinhibition is coupled with excitation. Similarly, maximum hyperpolarization is achieved by the coupling of disfacilitation with inhibition. In our experiments, this is achieved by having either an intact Ia reciprocal inhibition systemor disrupting reciprocal inhibition by cutting the tendons to antagonist muscles.

Our recent studies show that extensor MNs in the decerebrate preparation receive a steady inhibitory background drive that is likely to bemainly due to Ia interneurons.24 We believe that the Ia reciprocal inhibition between antagonist muscle groups provides the inhibitory background needed to interact with excitation and constitute the push–pull relationship. Through this relationship, we propose that the desirable effects of the PIC can be preserved and the undesirable effects minimized. Studies are presently underway to test this hypothesis using voltage clamp in MNs and reflex measurements in muscles to test the hypothesis that passive sensory input to MNs is organized in a push–pull fashion.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Cushing S, Bui T, Rose PK. Effect of nonlinear summation of synaptic currents on the input-output properties of spinal motoneurons. J. Neurophysiol. 2005;94:3465–3478. doi: 10.1152/jn.00439.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sjostrom PJ, Rancz EA, Roth A, Hausser M. Dendritic excitability and synaptic plasticity. Physiol. Rev. 2008;88:769–840. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00016.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baldissera F, Hultborn H, Illert M. Integration in spinal neuronal systems. In: MotorControl,part 1. V.B. Brooks, editor. Handbook of Physiology. Section 1 : The Nervous System. Vol. 2. Bethesda: American Physiological Society; 1981. pp. 509–595. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Binder MD, Heckman CJ, Powers CK. Relative strengths and distributions of different sources pf synaptic input to the motoneurone pool: implications for motor unit recruitment. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2002;508:207–212. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0713-0_25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heckman CJ, Lee RH, Brownstone RM. Hyperexcitable dendrites in motoneurons and their neuromodulatory control during motor behavior. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:688–695. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hultborn H, Brownstone RB, Toth TI, Gossard JP. Key mechanisms for setting the input-output gain across themotoneuron pool. Prog. Brain Res. 2004;143:77–95. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(03)43008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krawitz S, Fedirchuk B, Dai Y, et al. State-dependent hyperpolarization of voltage threshold enhances motoneurone excitability during fictive locomotion in the cat. J. Physiol. 2001;532:271–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0271g.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fedirchuk B, Dai Y. Monoamines increase the excitability of spinal neurones in the neonatal rat by hyperpolarizing the threshold for action potential production. J. Physiol. 2004;557:355–361. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.064022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Powers RK, Binder MD. Input-output functions of mammalian motoneurons. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2001;143:137–263. doi: 10.1007/BFb0115594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rekling JC, Funk GD, Bayliss DA, et al. Synaptic control of motoneuronal excitability. Physiol. Rev. 2000;80:767–852. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.2.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Powers RK, Binder MD. Input-output functions of mammalian motoneurons. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2001;143:137–263. doi: 10.1007/BFb0115594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carlin KP, Jones KE, Jiang Z, et al. Dendritic L-typecalcium currents in mouse spinal motoneurons: implications for bistability. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2000;12:1635–1646. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hultborn H, Denton ME, Wienecke J, Nielsen JB. Variable amplification of synaptic input to cat spinal motoneurones by dendritic persistent inward current. J. Physiol. 2003;552:945–952. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.050971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee RH, Heckman CJ. Adjustable amplification of synaptic input in the dendrites of spinal motoneurons in vivo. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:6734–6740. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-17-06734.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heckman CJ, Hyngstrom AS, Johnson MD. Active properties of motoneurone dendrites: diffuse descending neuromodulation, focused local inhibition. J. Physiol. 2008;586:1225–1231. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.145078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobs BL, Martin-Cora CA, Fornal FJ. Activity of medullary serotonergic neurons in freely moving animals. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 2002;40:45–52. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00187-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aston-Jones G, Chen S, Zhu Y, Oshinsky ML. A neural circuit for circadian regulation of arousal. Nat. Neurosci. 2001;4:732–738. doi: 10.1038/89522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwindt PC, Crill WE. Properties of a persistent inward current in normal and TEA-injected motoneurons. J. Neurophysiol. 1980;43:1700–1724. doi: 10.1152/jn.1980.43.6.1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwindt PC, Crill WE. Role of a persistent inward current in motoneuron bursting during spinal seizures. J. Neurophysiol. 1980;43:1296–1318. doi: 10.1152/jn.1980.43.5.1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hounsgaard J, Hultborn H, Jespersen B, Kiehn O. Bistability of alpha-motoneurones in the decerebrate cat and in the acute spinal cat after intravenous 5-hydroxytryptophan. J. Physiol. 1988;405:345–367. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee RH, Heckman CJ. Bistability in spinal motoneurons in vivo: systematic variations in persistent inward currents. J. Neurophysiol. 1998;80:583–593. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.2.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee RH, Heckman CJ. Bistability in spinal motoneurons in vivo: systematic variations in rhythmic firing patterns. J. Neurophysiol. 1998;80:572–582. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.2.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bennett DJ, Hultborn H, Fedirchuk M, Gorassini B. Short-termplasticity in hindlimb motoneurons of decerebrate cats. J. Neurophysiol. 1998;80:2038–2045. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.4.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hyngstrom MD, Johnson AS, Miller JF, Heckman CJ. Intrinsic electrical properties of spinal motoneurons vary with joint angle. Nat. Neurosci. 2007;10:363–369. doi: 10.1038/nn1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee RH, Kuo JJ, Jiang MC, Heckman CJ. Influence of active dendritic currents on input-output processing in spinal motoneurons in vivo . J. Neurophysiol. 2003;89:27–39. doi: 10.1152/jn.00137.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Björklund A, Skagerberg G. Descending monoaminergic projections to the spinal cord. In. In: Sjolund B, Bjorklund A, editors. Brain Stem Control of Spinal Mechanisms. Amsterdam: Elsevier Biomedical Press; 1982. pp. 55–88. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuo JJ, Lee RH, Johnson MD, et al. Active dendritic integration of inhibitory synaptic inputs in vivo. J. Neurophysiol. 2003;90:3617–3624. doi: 10.1152/jn.00521.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holstege JC, Kuypers HG. Brainstem projections to spinal motoneurons: an update. Neuroscience. 1987;23:809–821. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(87)90160-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hyngstrom A, Johnson M, Schuster CJ, Heckman J. Movement-related receptive fields of spinal motoneurones with active dendrites. J. Physiol. 2008;586:1581–1593. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.149146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eccles RM, Lundberg A. Integrative pattern of Ia synaptic actions on motoneurones of hip and knee muscles. J. Physiol. 1958;144:271–298. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1958.sp006101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lundberg A. Reflex pathways from group II muscle afferents 1. Distribution and linkage of reflex actions to alpha-motoneurons. Exp. Brain Res. 1987;65:271–281. doi: 10.1007/BF00236299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nichols TR, Cope TC. The organization of distributed proprioceptive feedback in the chronic spinal cat. In: Cope TC, editor. Motor Neurobiology of the Spinal Cord. London: CRC Press; 2001. pp. 305–326. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bui TV, Grande G, Rose PK. Multiple modes of amplification of synaptic inhibition to motoneurons by persistent inward currents. J Neurophysiol. 2008;99:571–582. doi: 10.1152/jn.00717.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bui TV, Grande G, Rose PK. Relative location of inhibitory synapses and persistent inward currents determines the magnitude and mode of synaptic amplification in motoneurons. J Neurophysiol. 2008;99:583–594. doi: 10.1152/jn.00718.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Curtis DR, Lacey G. Prolonged GABAB receptor-mediated synaptic inhibition in the cat spinal cord: an in vivo study. Exp. Brain Res. 1998;121:319–333. doi: 10.1007/s002210050465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruscheweyh R, Sandkuhler J. Lamina-specific membrane and discharge properties of rat spinal dorsal horn neurones in vitro. J. Physiol. 2002;541:231–244. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.017756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steriade M. Impact of network activities on neuronal properties in corticothalamic systems. J. Neurophysiol. 2001;86:1–39. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Destexhe A, Rudolph M, Pare D. The high-conductance state of neocortical neurons in vivo. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2003;4:739–751. doi: 10.1038/nrn1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feldman AG, Orlovsky GN. Activity of interneurons mediating reciprocal Ia inhibition during locomotion. Brain Res. 1975;84:181–194. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90974-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deliagina TG, Orlovsky GN. Activity of Ia inhibitory interneurons during fictitious scratch reflex in the cat. Brain Res. 1980;193:439–447. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90176-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]