Abstract

A 44-year-old Albanian male was consulted and diagnosed with dementia. His magnetic resonance imaging suggested diffuse white matter changes. The suspicion of cerebral autosomal-dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) was raised, and a genetic analysis confirmed such a suspicion through uncovering a pathogenic mutation at the level of exon 4 (c.475C>T) of chromosome 19. The patient came from a large family of 13 children, all of whom underwent clinical, genetic, and imaging examination. The pathogenic mutation was found present only in his eldest sister (50 years old), and she presented also very suggestive signs of CADASIL in her respective imaging study, but without any clinically significant counterpart. All other siblings were free from clinical and radiological signs of the disorder. Our opinion was that we were dealing with a mutation showing a very low level of penetrance, with only two siblings affected in a large Albanian family with 13 children.

Keywords: CADASIL, headache, dementia, subcortical infarcts, leukoencephalopathy

Video abstract

Introduction

Cerebral autosomal-dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) represents a monogenic form of hereditary cerebral microangiopa-thy, and mutations are confined at the gene NOTCH3 of chromosome 19.1 The disease is characterized through repeated cerebrovascular events, but also with pseudobulbar palsy and multi-infarct dementia, although psychiatric symptomatology, spasticity and migraine have been frequently encountered.2,3 The disease should have been clinically described several decades before Tournier-Lasserve et al published two pioneering manuscripts, the first of which forecast the autosomal-dominant nature of the disease, and the second of which mapped the gene mutation to chromosome 19q12.4,5

A challenge for authors, however, ever since the diagnostic criteria were formulated, has been the finding of an explanation for CADASIL’s extremely variable symptomatology. In fact, behavioral changes and affective disorders with depressive or manic tonality might be the only clinical symptoms in some patients; some sources are even trying to diagnose it posthumously in famous authors such as Nietzsche, based on their psychological profile.6,7

Though the triadic symptomatology composed of cerebral ischemia, migraine-type headaches, and psychic changes, such as initially proposed by Tournier-Lasserve et al,4 remains valid, a panoply of other occurrences have been reported, including cerebral hemorrhagic infarcts, nonconvulsive epileptic status, and even an uncommon encephalopathy that might progress to coma.8–10

Case report

We describe here the case of two siblings from a large Albanian family, and their clinical course, with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings and genetic data.

The fourth child of the family, a male adult aged 44 years, was the first to get diagnosed. Coming from a deep rural area, he was sent to the closest hospital district due to severe behavioral changes. The symptomatology, according to relatives, had been present since approximately 1 year before medical advice was sought. He was diagnosed at the first neurological visit with dementia (Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE] score was 17 points).

Neurological examination suggested brisk deep tendon reflexes in all extremities but no pyramidal signs (Babinski, Hoffmann, and Rossolimo reflexes were absent). His left limbs were weaker to the degree of subclinical paresis (motor strength 4/5), with no clinical deficits in the contralateral areas. Hemihypesthesia was suggested when the patient was scrutinized for the light touch and proprioception. Palmomental and grasping signs were found to be positive, and spatial disorientation with short-term amnesia was visible, conforming to the dementia state. The emotional state was labile, but otherwise reflected the severe cognitive decline.

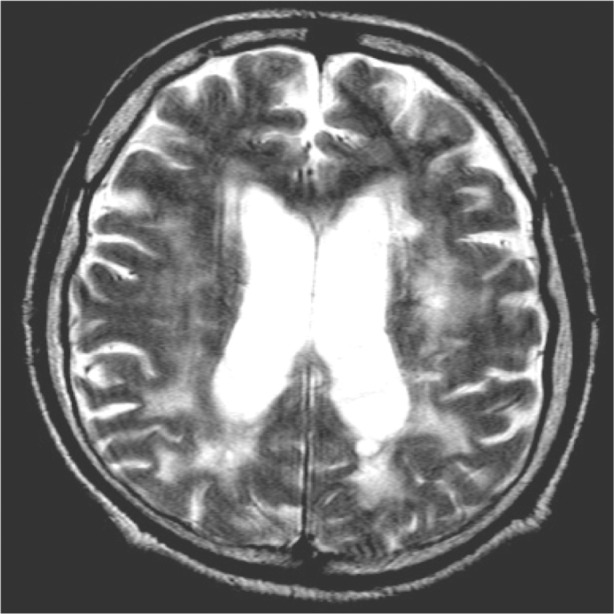

In spite of the lack of other important deficits of major neurological spheres, such as stroke-like episodes or motor deficits important enough to justify hospitalization, an MRI was requested and performed. Leukoencephalopathy was suggested, with diffuse, multifocal, and confluent lesions of white cerebral matter (Figure 1). A clinical and radiological suspicion of Cerebral Autosomal-Dominant Arteriopathy with Subcortical Infarcts and Leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) was formulated. The patient had been hypertensive for at least 5 years; he had stopped consuming alcohol 2 years before the diagnosis of CADASIL was made, due to an episodic hematemesis that was considered related to erosive gastritis. Actually, he had had no specific treatment for stomach problems and was free from complaints; impaired glucose tolerance (fasting glucose values higher than 110 mg/dL on 2 consecutive days) was suggested on blood analysis and was treated only through diet.

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging scan of the brain of the first patient (TQ, 44 years old; axial section) showing diffuse hyperintensities involving the white matter, mainly in the posterior cerebral areas.

Abbreviation: TQ, first patient.

The genetic test performed proved that the clinical suspicion of CADASIL had a molecular counterpart. In fact, the genetic analysis was made through automatic sequencing of exons 3 and 4. Such an analysis showed a pathogenic mutation at the level of exon 4, precisely c.475C>T, which led to the amino acid substitution Arg133Cys.

The genetic analysis of all other children of the family, including their mother (the father had died several years before) found the same mutation in the eldest child (the first daughter of the family), aged 50 years. There was a lack of medical data related to the cause of death of the father. Stroke was raised as a general suspicion by relatives, but the deceased (clearly an alcoholic) had never been hospitalized, and according to their reports had had a comatose period of less than 1 week prior to death, which occurred at home.

A thorough neuropsychological as well as neurological consultation was performed on both siblings presenting with the aforementioned mutation. The eldest sister (with the same mutation of c.475C>T at exon 4) presented only with tensive headaches, which were thought to be related to cervical spondyloarthrosis, but otherwise she was free from complaints. The psychiatrist consulting the woman suggested only a mild generalized anxiety (Hamilton Anxiety Scale score 14 points out of a maximum of 30), but otherwise her mood was normal, with no signs of subclinical depression (Beck Depression Inventory score 8 points, corresponding with normal ups and downs according to the inventory).

Doppler sonography of carotid arteries was performed on both siblings. The first patient (TQ) had a left-carotid stenosis of 50%–55% and a right-side stenosis of less than 40%; both stenotic changes were considered as hemodynamically not important. The same conclusion was given from the examining radiologist for the second patient (TL) as well, whose carotid arteries were found with stenosis not surpassing a value of 30% bilaterally, and thus hemodynamically not important either.

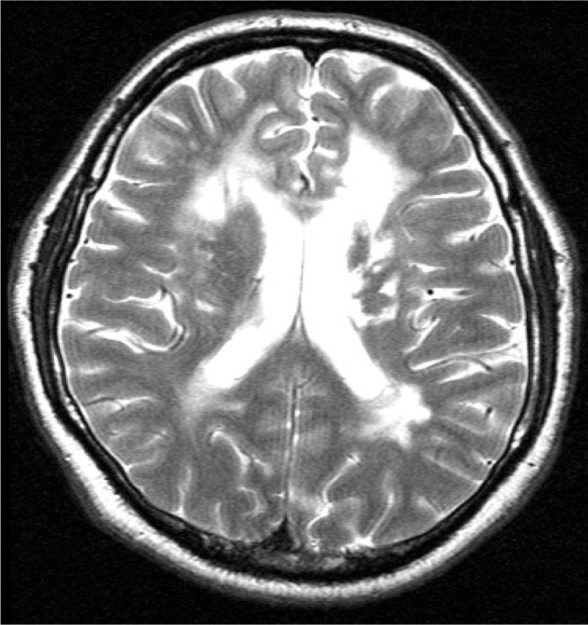

MRIs were performed on all other members of the family, though no genetic mutation was suggested apart from the two siblings mentioned above. No abnormalities were found on imaging. Meanwhile, the MRI of the oldest daughter was also suggestive of CADASIL (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging scan of the brain of the second patient (TL, 50 years old; axial section) showing periventricular confluent lesions, of a somewhat smaller extent when compared with the first patient.

Abbreviation: TL, second patient.

The clinical picture of the two siblings and their medical history are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics, MRI, genetic, and neurological findings

| Patient | Age | Main complaints | Imaging finding (MRI) | Other risk factors | Delay from first diagnosis made | Genetic finding | Objective neurological status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TQ (male) | 44 years | Behavioral changes | Diffuse white matter hyperintensities | HTA, previous history of alcoholism, IGT | 1 year | c.475C>T | Slight left motor deficit (4/5); hemihypesthesia; dementia (MMSE 17/30) |

| TL (female) | 50 years | Tensive headache | Periventricular hypersignals | None | NA | c.475C>T | No objective changes; MMSE 28 points |

Abbreviations: HTA, hypertension; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; NA, not applicable; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; TQ, first patient; TL, second patient.

Discussion

The clear discrepancy in the clinical features of CADASIL in two middle-aged Albanian siblings we have described is important enough to raise again the issue of the clinical variability of the disorder. In fact, we had almost the same radiological image and an identical genetic mutation leading to the diagnosis (c.475C>T, exon 4, chromosome 19). The mutation we uncovered in two siblings of this family results from the substitution of arginine to cysteine at codon 133 (Arg133Cys); it represents a single base alteration occurring on the NOTCH3 gene. Such a mutation is not unknown to authors referring to CADASIL cases; in fact, Scottish and Chinese scholars have referred to it in two papers, with the second group of authors concluding that the penetrance of the mutation was not complete, and that only individuals exposed to known vascular risk factors develop the disease.11,12 However, this mutation was not noted in other large-scale studies, nor in a study of 28 Italian families with NOTCH3 mutations, nor in another larger study of 65 families: the British CADASIL prevalence study.13,14

The clinical spectrum of CADASIL has been widely studied, and authors have suggested that other factors might modulate the clinical expression. Cardiovascular risk factors seem to play an important role in such expression.15 Mutation site and additional modulating factors (homocysteine, apolipoprotein E genotype, etc) will still have an impact on the poor genotype–phenotype correlation in CADASIL.14 The role of sex as an independent factor has been scrutinized as well, with the old-formulated theory of the presumably protective role of ovarian hormones coming out again, since the cognitive decline and dementia is clearly more severe in men.16

Attempts have been made as well to stratify risk factors and to stage the clinical severity and radiological course of CADASIL. Carotid markers of atherosclerosis have been evaluated through sonography, and correlations between carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT) and dementia or disability scores have been suspected, but not definitely proven.17 Being principally a small-vessel arteriopathy, such a conclusion is not unexpected; we have studied the correlations between CIMT value as a marker of atherosclerotic progression and diabetic retinopathy (considered mainly as a microangiopathy), and the findings were similarly suggestive of an unimportant association between the two phenomena.18

The radiological course of CADASIL has been depicted in three stages: stage I (patients 20–40 years old) with migraine and white matter lesions found in MRI; stage II (patients 40–60 years old) with stroke, transient ischemic attacks, and psychosis, and with advanced MRI changes; and stage III (patients older than 60 years), with dementia and diffuse leukoencephalopathy.19

Making a diagnosis of CADASIL when the clinical picture is combined with characteristic radiological changes is not difficult; however, genetic analysis is necessary to confirm the diagnosis. There have been authors proposing the presence of a suggestive clinical picture, as sufficient for making the diagnosis – the findings of brain MRI together with changes encountered in the histopathological skin biopsies – thus bypassing genetic analysis.20 Unfortunately, the sensitivity of detection of the presence of granular osmiophilic material in the basement membrane, as detected through histopathology, is as low as 50%.21

Due to the large number of exons in chromosome 19 and an even higher number of mutations uncovered thus far, genetic analysis might be time-consuming. Nevertheless, in our opinion, and also due to the fact that mutations have a geographical distribution, genetic analysis is a mainstream diagnostic tool that has to be utilized.13

Conclusion

The case of two siblings showing very similar radiological characteristics of CADASIL and both having the same genetic mutation that confirmed such a diagnosis raises again the issue of the clinical variability of the disorder. Other nongenetic factors seem important, since the patient we diagnosed first had profound dementia, was a male aged 44 years, and had other vascular risk factors. A completely different clinical picture was presented by his older sister, 50 years old, who was free from characteristic clinical symptoms and signs of CADASIL. It seems necessary therefore, to consider other factors before making a very careful prognosis, for such a highly variable clinical disorder.22 We also suggest that the mutation presented in this large family with 13 children logically shows a very low level of penetrance; such low penetrance has been reported as well by Asian authors.12,23 With data still unclear regarding the overall prevalence of CADASIL, which is mainly reported in Caucasian families, elevated disease frequencies have been registered in small isolated populations, where even a founder effect is formulated.24 Due to these aspects, with genetic analysis confirming a diagnosis who presents a highly variable picture, we think that MRI evaluation of asymptomatic carriers of the mutation and close clinical follow-up, seem to be warranted.

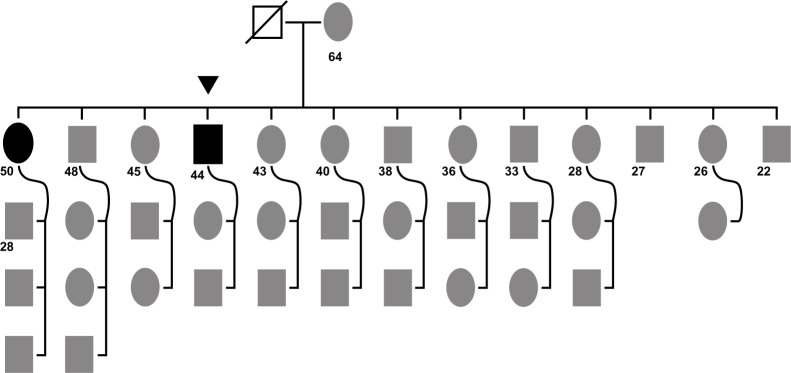

Figure 3.

Case study family tree.

Notes: A large family (13 children)with the mother (64 years old) giving birth to her first child as a minor (14 years old). The father was deceased at time of data collection. The first child born (female, 50 years old at the time of data collection, bold black oval) and the fourth child (male, 44 years old at the time of data collection; black triangle) were diagnosed with cerebral autosomal-dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy. Numbers depict ages of adults at the time of sampling; rectangles, male probands; ovals: female probands; black triangle, patient initiating genetic workup (index case). • Black oval, affected individual (female); ■ black rectangle, affected individual (male); ⍁ deceased (male).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Shahien R, Bianchi S, Bowirrat A. Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy in an Israeli family. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2011;7:383–390. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S19399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mikol J, Hénin D, Baudrimont M, et al. CADASIL: aspects phénotypiques inhabituels et observations anatomo-pathologiques dans deux nouvelles familles françaises. [Atypical CADASIL phenotypes and pathological findings in two new French families.] Rev Neurol (Paris) 2001;157(6–7):655–667. French. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sabbadini G, Francia A, Calandriello L, et al. Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL). Clinical, neuroimaging, pathological and genetic study of a large Italian family. Brain. 1995;118(Pt 1):207–215. doi: 10.1093/brain/118.1.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tournier-Lasserve E, Iba-Zizen M, Romero N, Bousser MG. Autosomal dominant syndrome with stroke-like episodes and leukoencephalopathy. Stroke. 1991;22(10):1297–1302. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.10.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tournier-Lasserve E, Joutel A, Melki J, et al. Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy maps to chromosome 19q12. Nat Genet. 1993;3(3):256–259. doi: 10.1038/ng0393-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hemelsoet D, Hemelsoet K, Devreese D. The neurological illness of Friedrich Nietzsche. Acta Neurol Belg. 2008;108(1):9–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perogamvros L, Perrig S, Bogousslavsky J, Giannakopoulos P. Friedrich Nietzsche and his illness: a neurophilosophical approach to introspection. J Hist Neurosci. 2013;22(2):174–182. doi: 10.1080/0964704X.2012.712825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rinnoci V, Nannucci S, Valenti R, et al. Cerebral hemorrhages in CADASIL: report of four cases and a brief review. J Neurol Sci. 2013;330(1–2):45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valko PO, Siccoli MM, Schiller A, Wieser HG, Jung HH. Non- convulsive status epilepticus causing focal neurological deficits in CADASIL. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78(11):1287–1289. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.124800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schon F, Martin RJ, Prevett M, Clough C, Enevoldson TP, Markus HS. “CADASIL coma”: an underdiagnosed acute encephalopathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74(2):249–252. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.2.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Razvi SS, Davidson R, Bone I, Muir KW. The prevalence of cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) in the west of Scotland. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(5):739–741. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.051847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tan ZX, Li FF, Qu YY, et al. Identification of a known mutation in Notch 3 in familiar CADASIL in China. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e36590. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dotti MT, Federico A, Mazzei R, et al. The spectrum of Notch3 mutations in 28 Italian CADASIL families. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(5):736–738. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.048207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singhal S, Bevan S, Barrick T, Rich P, Markus HS. The influence of genetic and cardiovascular risk factors on the CADASIL phenotype. Brain. 2004;127(Pt 9):2031–2038. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adib-Samii P, Brice G, Martin RJ, Markus HS. Clinical spectrum of CADASIL and the effect of cardiovascular risk factors on phenotype: study in 200 consecutively recruited individuals. Stroke. 2010;41(4):630–634. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.568402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gunda B, Hervé D, Godin O, et al. Effects of gender on the phenotype of CADASIL. Stroke. 2012;43(1):137–141. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.631028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mawet J, Vahedi K, Aout M, et al. Carotid atherosclerotic markers in CADASIL. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;31(3):246–252. doi: 10.1159/000321932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mazreku F, Abdushi S, Kryeziu F, Vyshka G. Carotid intima-media thickness seems not to correlate with the severity of diabetic retinopathy. Sci J Med Sci. 2013;2(5):83–88. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vérin M, Rolland Y, Landgraf F, et al. New phenotype of the cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy mapped to chromosome 19: migraine as the prominent clinical feature. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1995;59(6):579–585. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.59.6.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krsmanović Z, Dincić E, Kostić S, et al. Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2011;68(5):455–459. doi: 10.2298/vsp1105455k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dotti MT. CADASIL: A hereditary cerebrovascular disease as model for common vascular ischemic dementia. J Siena Acad Sci. 2009;1(1):34–35. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uyguner ZO, Siva A, Kayserili H, et al. The R110C mutation in Notch3 causes variable clinical features in two Turkish families with CADASIL syndrome. J Neurol Sci. 2006;246(1–2):123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watanabe M, Adachi Y, Jackson M, et al. An unusual case of elderlyonset cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) with multiple cerebrovascular risk factors. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012;21(2):143–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi JC. Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy: a genetic cause of cerebral small vessel disease. J Clin Neurol. 2010;6(1):1–9. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2010.6.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]