A 54-year-old male Matsigenka native from the Manu jungle of Peru presented with the eggs shown in Figure 1. Kato Katz (Figure 2) testing revealed 1,500 eggs/g stool. The white blood cell count with differential, liver enzymes, and sputum examination were normal. No treatment was administered; however, repeated stool testing was negative. Pseudocapillariasis caused by Capillaria hepatica was diagnosed. The transient shedding of C. hepatica eggs (which are not usually found in the stools in hepatic capillariasis), lack of eosinophilia, and normal liver enzymes supported the diagnosis. The patient admitted eating liver of a South American Tapir (Tapirus terrestris) shortly before testing. These animals harbor unembryonated non-infective C. hepatica eggs in the liver parenchyma.1 The unembryonated eggs reach the environment after the infected animal dies or eggs are shed in the stools of predators feeding on infected carcasses. After spending 4–8 weeks in the environment, eggs become embryonated and are able to infect the liver if ingested. Hepatic capillariasis is an uncommon human zoonotic disease distributed worldwide. It causes prolonged fever, hepatomegaly, and abdominal pain associated with eosinophilia. In contrast, C. hepatica pseudoinfection caused by feeding on livers harboring unembryonated eggs is asymptomatic.2

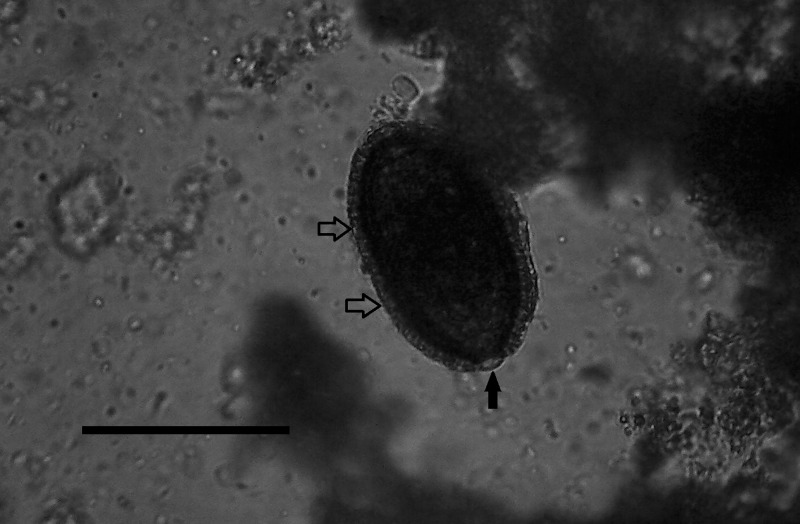

Figure 1.

Spontaneous rapid sedimentation test. Egg with a thick striated wall (open arrows) and flat bipolar plugs (arrow) compatible with C. hepatica (Magnification: 400×; scale bar: 50 μm).

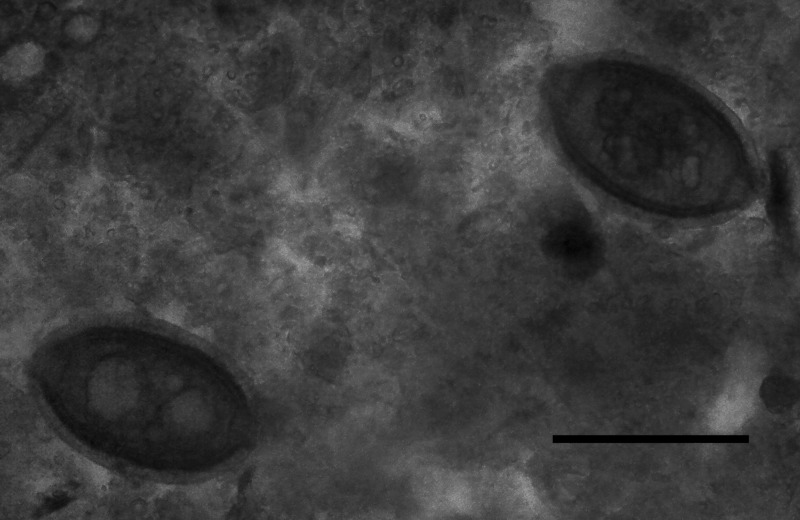

Figure 2.

Kato Katz test showing the same type of eggs (Magnification: 400×; scale bar: 50 μm).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Mark Eberhard from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for assistance in the final identification of Capillaria hepatica. We thank Ms. Nancy Santullo and Mr. Caleb Matos from the House of the Children non-profit organization for providing the specimens for testing.

Footnotes

Authors' addresses: Miguel M. Cabada, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX, and Department of Medicine, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Peru, E-mail: micabada@utmb.edu. Martha Lopez, Department of Medicine, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Peru, E-mail: martlop2000@gmail.com. A. Clinton White Jr., Department of Internal Medicine, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX, E-mail: acwhite@utmb.edu.

References

- 1.Carvalho-Costa FA, Silva AG, de Souza AH, Moreira CJ, de Souza DL, Valverde JG, Jaeger LH, Martins PP, de Meneses VF, Araújo A, Bóia MN. Pseudoparasitism by Calodium hepaticum (syn. Capillaria hepatica; Hepaticola hepatica) in the Negro River, Brazilian Amazon. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103:1071–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fuehrer HP, Igel P, Auer H. Capillaria hepatica in man—an overview of hepatic capillariosis and spurious infections. Parasitol Res. 2011;109:969–979. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2494-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]