Abstract

In this work, we report the cloning and characterization of endo-β-1,4-glucanase (EGase) genes (TaEG) in the common wheat line three pistils. Three TaEG homoeologous genes (TaEG-4A, TaEG-4B and TaEG-4D) were isolated and found to be located on chromosomes 4AL, 4BS and 4DS, respectively. The three genes showed high conservation of their coding nucleotide sequences and 3 untranslated region. The putative TaEG protein had a molecular mass of 69 kDa, a theoretical pI of 9.39 and a transmembrane domain of 74–96 amino acids in the N-terminus that anchored the protein to the membrane. The genome sequences of TaEG-4A, TaEG-4B and TaEG-4D contained six exons and five introns. All of the introns, except for intron IV, varied in length and sequence composition. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that TaEG was most closely related to rice (Oryza sativa) OsGLU1. The TaEG transcript levels increased significantly during the subsidiary pistil primordium differentiation phase (spike size ∼7–10 mm) in Chuanmai 28 TP (CM28TP). These data provide a basis for future research into the function of TaEG and offer insights into the molecular mechanism of the three pistils mutation in wheat.

Keywords: cloning; endo-β-1,4-glucanase; three pistils line; wheat

Introduction

Endo-β-1,4-glucanases (EGases) are enzymes that hydrolyze polysaccharides containing a 1,4-β-glucan backbone and are produced by prokaryotes and eukaryotes (Henrissat et al., 1989; Beguin, 1990; Watanabe et al., 1998; Byrne et al., 1999; Rosso et al., 1999). These enzymes have also been classified as cellulases because of their central role in cellulose degradation and their potential to modify cellulose-containing materials (Bisaria and Mishra, 1989; Beguin, 1990; Beguin and Aubert, 1994). Sequence analysis has shown that all cloned plant EGases can be classified into two subfamilies (Nicol et al., 1998). One of these subfamilies consists of soluble secreted EGases such as avocado Cel1, pepper CX1 and tomato Cel2 that are expressed specifically during fruit ripening (Christoffersen et al., 1984; Lashbrook et al., 1994; Ferrarese et al., 1995), while others such as bean BAC1, soybean SAC1 and elder JET1, are associated with abscission (Tucker et al., 1988; Kemmerer and Tucker, 1994; Taylor et al., 1994). The other subfamily consists of membrane-anchored proteins located in the plasma membrane that also contribute to normal cellulose formation (Brummell et al., 1997a; Nicol et al., 1998; Del Campillo, 1999; Molhoj et al., 2001). This subfamily includes the Arabidopsis KOR gene and the O. sativa OsGLU1 gene that are involved in cell elongation (Nicol et al., 1998; Lane et al., 2001; Zhou et al., 2006).

The common wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) line three pistils (TP), which was selected by Peng (2003) from the “trigrain” wheat cultivar, is a valuable mutant for improving wheat yield. Since the TP mutation has normal spike morphology but produces three pistils per floret it has potential for increased grain number per spike. In a previous study, a sequence from an expressed sequence tag (EST) was initially identified in a TP mutation in wheat using an annealing control primer system (ACP) (Yang et al., 2011). Blast searches of this sequence against the GenBank database revealed that it was homologous to the EGase gene. To our knowledge, the role of EGase genes in wheat development has not yet been reported.

As part of an investigation into the function of the wheat EGase gene (TaEG) in pistil development in this work we have cloned, characterized and phylogenetically analyzed the TaEG gene in the common wheat line three pistil. We also examined the expression patterns of this gene in different developmental stages of young spikes.

Materials and Methods

Plant material

Chuanmai 28 TP (CM28TP), a near-isogenic line of the common wheat line Chuanmai 28 carrying the Pis1 gene derived from the TP mutant (Yang et al., 2012), and the recurrent parent T. aestivum cv. Chuanmai 28 (CM28) were used in this study. The near-isogenic line and the recurrent parent were cultivated in the field at the China West Normal University in Nanchong, China. Young spikes at the reproductive stage were collected and examined with an Olympus SZX9 stereomicroscope to accurately determine their developmental stage. Subsidiary pistil spikes in the primordial stage of differentiation (spike size ∼7–10 mm) were used as a source of RNA and DNA for cloning the cDNA and sequencing the TaEG gene. Spikes of CM28TP and CM28 at various developmental stages (spikes 2–5, 5–7, 7–10, 10–13, 13–15, 15–17 and 17–20 mm in length) were selected for real-time PCR. In addition, the nullisomic-tetrasomic (NT) lines and ditelosomic (Dt) lines Dt1AL, Dt1AS, Dt2AS, Dt3AL, Dt3AS, Dt4AL, N4AT4B, Dt5AL, N5AT5B, Dt6AL, Dt6AS, Dt7AL, Dt7AS, Dt1BL, Dt1BS, Dt2BL, N2BT2A, Dt3BL, Dt3BS, Dt4BL, Dt4BS, Dt5BL, N5BT5D, Dt6BS, N6BT6D, Dt7BL, Dt7BS, Dt1DL, Dt1DS, Dt2DL, Dt2DS, Dt3DL, Dt3DS, Dt4DL, Dt4DS, Dt5DL, N5DT5A, Dt6DL, Dt6DS, Dt7DL and Dt7DS derived from CS (Sears, 1954; Endo and Gill, 1996) were used for the chromosomal mapping of TaEG.

DNA and RNA isolation

Genomic DNA was isolated from young spikes of CM28TP and CM28 and fresh leaves of the NT and Dt lines, as described by Porebski et al. (1997). The DNA was dissolved in Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer and stored at −20 °C. Total RNA was isolated from young spikes as described by Manickavelu et al. (2007). The RNA was dissolved in RNase-free double distilled water (ddH2O) and stored at −70 °C. The quality of the DNA and RNA was confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis and the nucleic acid concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically based on the 260/280 nm absorbance ratio.

Cloning and chromosomal mapping of TaEG

A TaEG EST (DETP-3) was initially identified in the three pistils mutation of wheat by using an annealing control primer system (ACP) (Yang et al., 2011). Blast search analysis indicated that a full length cDNA (GenBank ID: AK373303) in barley shared perfect identity with the TaEG EST. The PCR primer pair TaEG-1 was designed with Primer Premier 5.0 based on the cDNA of AK373303 (Table 1). The cDNA and genomic DNA sequences were amplified using the same primers (TaEG-1). PCR amplification was done in a thermocycler (My-Cycle, Bio-Rad, San Diego, CA, USA) in a volume of 50 βL containing 100 ng of genomic DNA or reverse transcriptase reaction product (see below for details), 100 μM of each dNTP, 1.5 mM Mg2+, 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase, 0.4 μM of each primer and 1PCR buffer. The PCR cycling conditions included pre-denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 4 min, and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The amplified products were visualized by gel electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels and then documented with a Gel Doc 2000TM system (Bio-Rad). The target DNA bands were recovered and purified from the gels using Qiaquick Gel extraction kits (QIAGEN, Shanghai, China). The purified PCR products were cloned in the pMD-19T vector according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Takata, Dalian, China). Transformants were plated on LB agar containing ampicillin. Clones with inserts were identified using blue/white colony selection. Positive clones were then screened and sequenced by Taihe Biotechnology Co. Ltd. (Beijing, China).

Table 1.

Primers used in this study.

| PCR target | Primer | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic and cDNA sequences | TaEG-1 | CCCTTCCGTTCCCATTCCAAGC | ACATGGCATGGTGATGATACT |

| Chromosomal location | TaEG-IN3 | GGATAATAAGCTCCCTGGTG | TACAATCGTAAGTGCCCTGT |

| Real-time PCR | TaEG-2 | GCGGGCAACGCTGGTCTA | GGGAACATTGGCGGCACA |

| Internal control | Ubiquitin | AAGGCGAAGATCCAGGACAAG | TGGATGTTGTAGTCCGCCAAG |

| Actin | ACGCTTCCTCATGCTATCCTTC | ATGTCTCTGACAATTTCCCGCT |

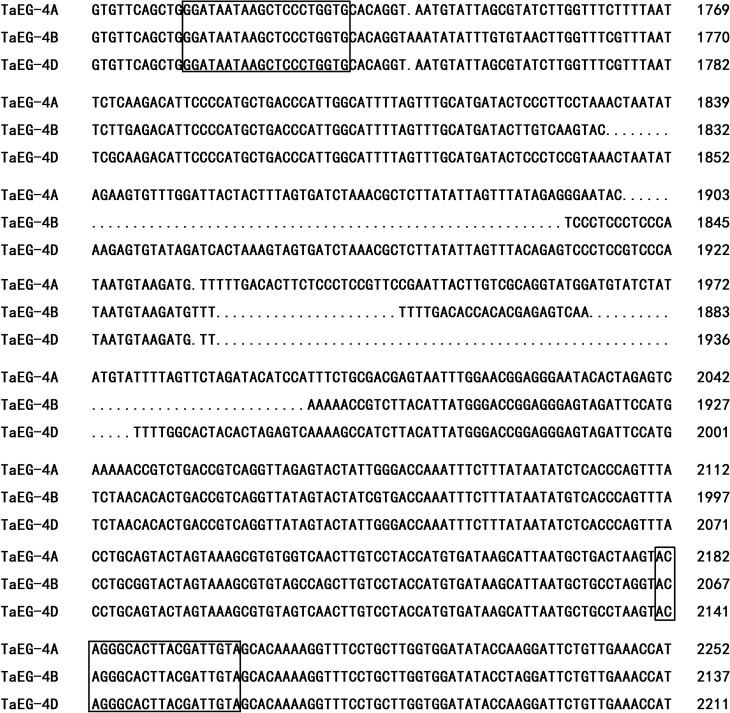

The chromosomal location of TaEG was mapped using the genomic DNA of 36 Dt lines and 5 NT lines (see above). The authenticity of the Dt lines and NT lines was confirmed with SSR markers before use. The gene-specific primers for TaEG-IN3 (Table 1) were designed based on intron which shows clear sequence variations among chromosomes A, B and D (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Alignment of the intron III sequences of TaEG-4A, TaEG-4B and TaEG-4D. The forward and reverse TaEG-IN3 primers used for chromosome location are boxed.

Molecular characterization of TaEG

The sequence data were analyzed with GenScan software. The open reading frame (ORF) of the cDNA sequence was searched using ORF finder software. A computation tool from the Swiss-Prot/TrEMBL entries was used to calculate the isoelectric point (pI) and molecular mass (Mr) of TaEG. The deduced TaEG sequence was investigated for the presence of signal peptide cleavage sites and transmembrane helices using software available through the SignalP 4.1 and SCOP servers. For homology analysis, the amino acid sequence of TaEG was compared with the sequences of other species using Blast 2.1.

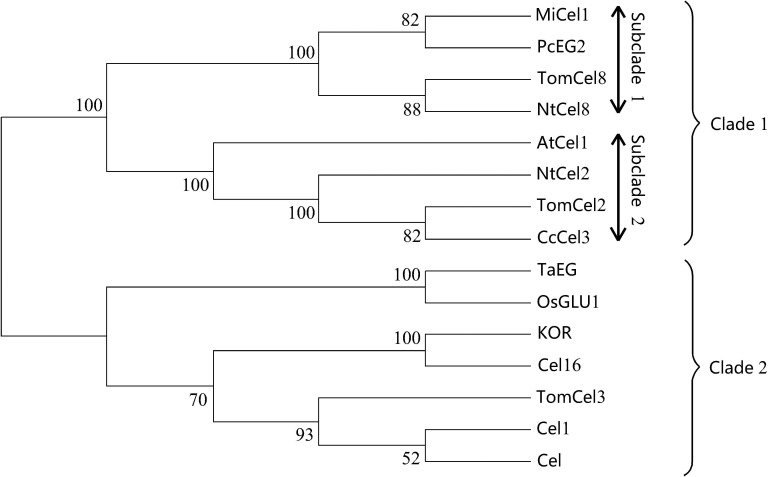

Multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis

The deduced amino acid sequence of TaEG was aligned with the EGase genes reported for other species using the ClustalW program (Thompson et al., 1994). Neighbor-joining trees of the EGase genes were generated with MEGA software version 5.0 (Saitou and Nei, 1987; Tamura et al., 2007) with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Gaps were treated as missing values. The amino acid sequences of EGase genes from Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh (AtCel1: X98544, KOR: NP_199783), Oryza sativa L. (OsGLU1: EEE58992), Solanum lycopersicum L. (TomCel2: U13055, TomCel3: U78526, TomCel8: AF098292), Piper nigrum L. (CcCel3: X97189), Nicotiana tabacum L. (NtCel2: AF362948, NtCel8: AF362949), Pyrus communis L. (PeEG2: BAC22691, Cel1: BAF42036), Mangifera indica L. (MiCel1: EF608067), Brassica napus L. (Cel16: CAB51903) and Gossypium barbadense L. (Cel: ADY68791) were obtained from NCBI.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from spikes of the near-isogenic line CM28TP and its recurrent parent, CM28, at various developmental stages (2–5, 5–7, 7–10, 10–13, 13–15, 15–17 and 17–20 mm in length). The cDNA was synthesized using a PrimeScript Perfect real-time RT reagent kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). The primers for TaEG-2 (Table 1) were designed using Primer Express 2.0 software to amplify 101-bp fragments of the TaEG gene. Real-time assays were done with SYBR green dye (TakaRa) using a Bio-Rad CFX96 real-time PCR platform. All of the samples were analyzed in triplicate and the fold change in RNA transcripts was calculated by the 2−ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001) with the wheat housekeeping genes ubiquitin (DQ086482) and actin (AB181911) as internal controls (Hama et al., 2004; Yamada et al., 2009).

Results

Cloning and chromosomal location of genomic and cDNA sequences

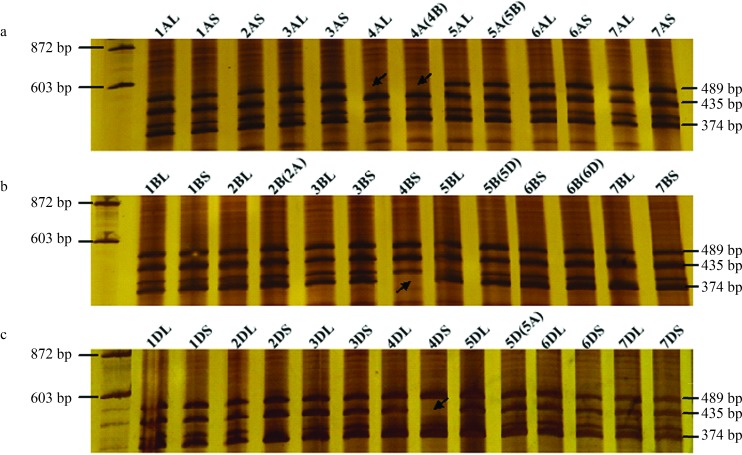

Cloning followed by PCR product analysis resulted in the identification and isolation of three genomic sequences (3625, 3510 and 3574 bp long) from CM28TP. Three bands (489, 435 and 374 bp) were amplified in CM28TP with gene-specific primers of TaEG-IN3. NT and Dt line analysis indicated that the TaEG-IN3 primer set amplified the expected three bands from all the NT and Dt lines, with the exception of DT4AL (lacked the 489-bp band), N4A-T4B (lacked the 489-bp band), Dt4BS (lacked the 374-bp band) and Dt4DS (lacked the 435 bp band) (Figure 2). Further analysis showed that the longest PCR product (3625 bp) was located on the long arm of chromosome 4A, the intermediate product (3574 bp) on the short arm of chromosome 4D and the shortest product (3510 bp) on the short arm of chromosome 4B. The three homologous genes were tentatively designated as TaEG-4A, TaEG-4D and TaEG-4B, respectively. The sequences were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers KC521526, KC521527 and KC521528.

Figure 2.

Chromosome mapping of the TaEG gene. DNA size markers are shown on the left of the gel. (A) TaEG-4A located on the long arm of chromosome 4A. (B) TaEG-4B located on the short arm of chromosome 4B. (C) TaEG-4D located on the short arm of chromosome 4D. Missing fragments are indicated by arrows.

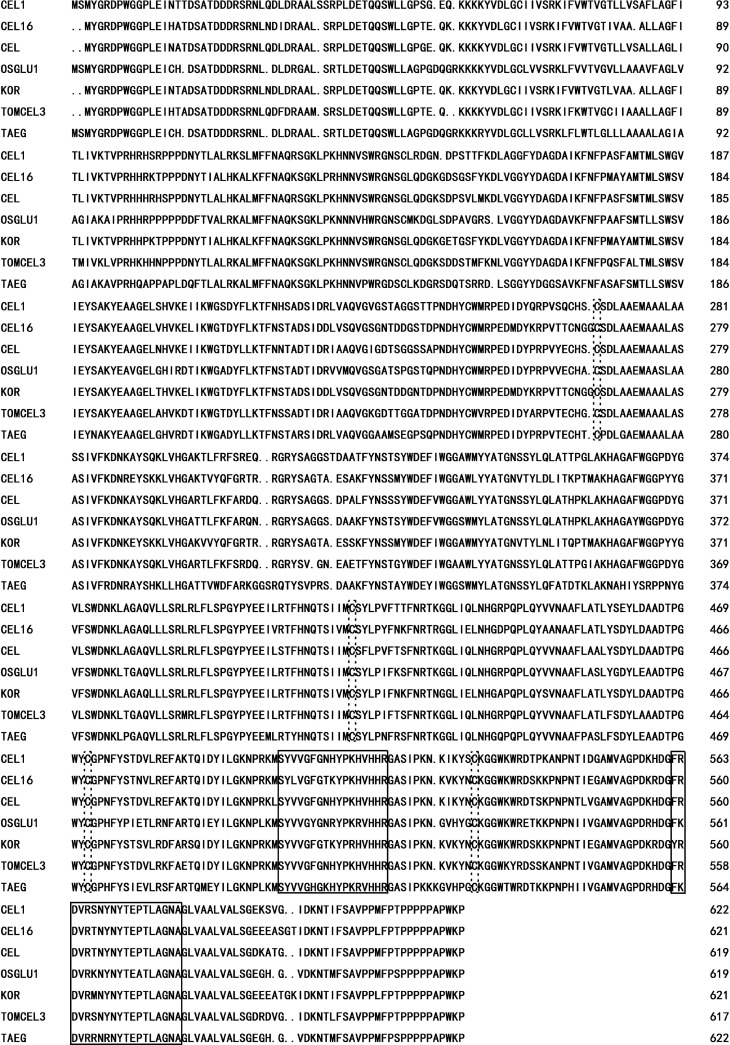

The cDNA from young spikes of CM28TP amplified with the TaEG-1 primer pair yielded a fragment of ∼2.1 kb. The PCR product was cloned into the PMD-19T vector and 15 clones were sequenced. Three distinct sequences of 2061 bp, 2084 bp and 2087 bp were identified (accession numbers: AC521523, AC521524 and AC521525, respectively), indicating that the band of ∼2.1 kb included comigrating cDNA of different homologous genes. The three homologous genes shared 100% homology in their coding and 3’ untranslated regions. The lengths of the 5’ untranslated region were 103 bp, 126 bp and 129 bp for TaEG-4A, TaEG-4B and TaEG-4D, respectively. The open reading frame (ORF) of TaEG was 1869 bp and coded for a deduced protein of 622 amino acids. Primary structure analysis using Swiss-Prot/TrEMBL revealed that the molecular mass of the putative TaEG protein was 69 kDa with a theoretical pI = 9.39. The putative TaEG protein lacked signal peptide cleavage sites but had a 74∼96 amino acid transmembrane domain. BLAST searches showed that the TaEG belonged to glycosyl hydrolase family 9 (Henrissat et al., 1989). Sequence alignment suggested that TaEG had high homology with other plant EGase proteins, all of which contained four Cys residues and two putative glycosyl hydrolase active sites, namely, ‘SY-VG-G-YP-VHHR’ and ‘F-DVR-N-NYTE-TLAGAN’ (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequence of TaEG with other plant EGase sequences. Four Cys residues and two putative glycosyl hydrolase active sites are indicated by the dotted line and solid line frames, respectively.

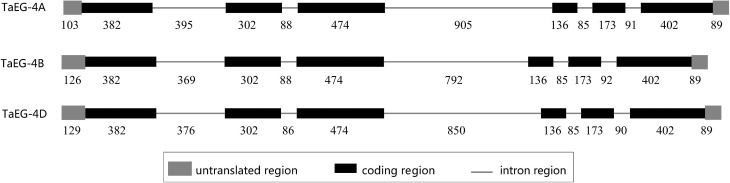

Structure of the TaEG genomic sequences

The TaEG-4A, TaEG-4B and TaEG-4D genomic sequences were 3625 bp, 3510 bp and 3574 bp long, respectively; their alignment and comparison with the corresponding cDNA sequences revealed the complex structure of the three homologous genes that consisted of six exons and five introns (Figure 4). The five introns fulfilled the GT-AG relue but varied markedly in length and sequence composition. The length of intron III was 905 bp, 792 bp and 850 bp in TaEG-4A, TaEG-4B and TaEG-4D, respectively, which was longer than the other four introns. Intron IV was 85 bp long in the three genes and was the shortest of the five introns. Intron I was 395 bp, 369 bp and 376 bp long in TaEG-4A, TaEG-4B and TaEG-4D, respectively. Intron II showed two lengths (88 bp and 86 bp) in TaEG-4A, TaEG-4B and TaEG-4D whereas intron V had three lengths, i.e., 91 bp, 92 bp and 90 bp.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of the TaEG gene.

Phylogenetic analysis of TaEG and plant EGases

To construct the phylogenetic tree, EGases from A. thaliana (AtCel1 and KOR), O. sativa (OsGLU1), S. lycopersicum (TomCel2, TomCel3 and TomCel8), P. nigrum (CcCel3), N. tabacum (NtCel2 and NtCel8), P. communis (PcEG2 and Cel1), M. indica (MiCel1), B. napus (Cel16) and G. barbadense (Cel) were analyzed. Figure 5 shows the tree obtained with the neighbor joining program using MEGA software and 1000 bootstrap replicates. Previous analysis identified two types of EGase in plants, namely, secretory EGase and transmembrane EGase, with the major difference between them being the presence of a signal peptide in the former and a transmembrane domain in the latter (Brummell et al., 1997a). In the present study, these EGases formed into two well-resolved clades (clades 1 and 2). Clade 1 contained eight members and the deduced proteins possessed a signal peptide, e.g., Tom Cel2, NtCel2 and PcEG2. Further inspection of clade 1 revealed the presence of two subclades (subclades 1 and 2), with the major difference between them being the presence (subclade 1) or absence (subclade 2) of a cellulose binding domain (CBD) (Zhou et al., 2004). Clade 2 contained seven members and the deduced proteins had a transmembrane domain, e.g., Tom OsGLU1, Cel16 and KOR. TaEG was located in clade 2 and showed a much greater similarity (83%) to O. sativa OsGLU1. Phylogenetic analysis also indicated that TaEG was a membrane-anchored protein.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic tree of TaEG and other homologous sequences. The numbers at the nodes indicate bootstrap values.

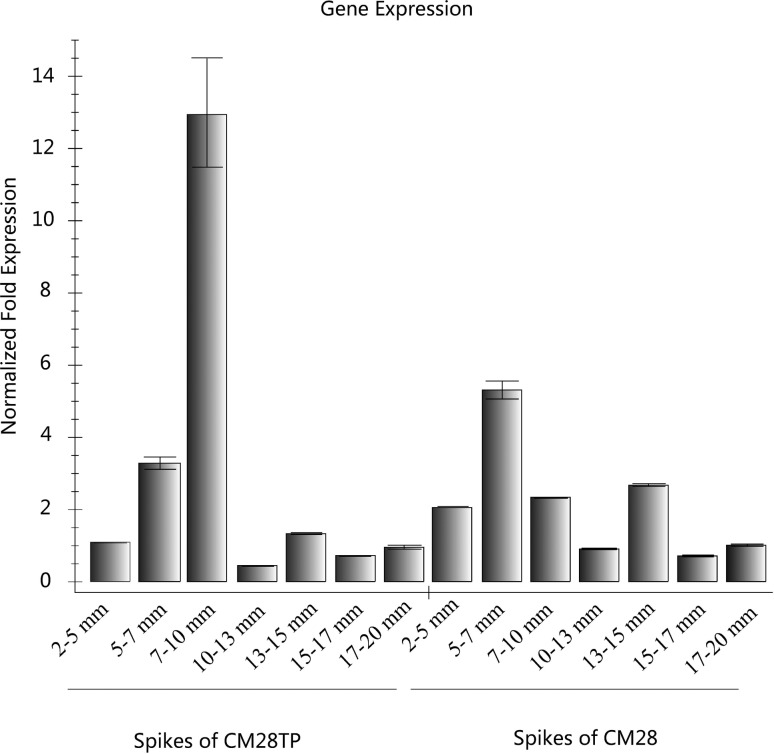

TaEG gene expression in developing spikes

Real-time PCR was used to study the pattern of TaEG expression in different tissues during the developmental stages of young spikes. As shown in Figure 6, in young spikes of CM28TP at stages 2–5, 5–7, 10–13, 13–15, 15–17 and 17–20 mm the transcript levels were similar to those observed in CM28. However, the transcript levels in young spikes of CM28TP at stages 7–10 mm were 5.6-fold higher than in CM28 spikes at the same stage.

Figure 6.

TaEG expression assessed by real-time PCR. Total RNA was isolated from spikes of the near-isogenic line CM28TP and its recurrent parent CM28 at various developmental stages. Ubiquitin and actin were used as internal controls. The transcript levels are shown as relative values and the columns represent the mean ± SEM of three replicates.

Discussion

An EST sequence (DETP-3) previously identified in the three pistil mutation of wheat using an annealing control primer system (ACP) was shown to have functions similar to those of the EGase gene (Yang et al., 2011). The EST was therefore tentatively designated as an T. aestivum endoglucanase gene (TaEG). In the present study, cDNA cloning and genome sequencing of TaEG from wheat showed that there are three homoeologous TaEG genes in wheat, namely, TaEG-4A, TaEG-4B and TaEG-4D located on chromosomes 4AL, 4BS and 4DS, respectively. The three homoeologous genes showed high conservation of the nucleotide coding sequences and 3 untranslated regions, with homologies up to 100%. The putative TaEG protein had a Mr of 69 kDa, a theoretical pI of 9.39 and a 74–96 amino acid transmembrane domain in the N-terminus. Despite variation in the nucleotide and amino acid sequences of TaEG from different plants, all of these proteins contained four Cys residues and two putative glycosyl hydrolase active sites (SY-VG-G-YP-VHHR and F-DVR-N-NYTE-TLAGAN) (Figure 3). The genome sequences of TaEG-4A, TaEG-4B and TaEG-4D contained six exons and five introns, all of which (except for intron IV) varied in length and sequence composition.

Endo-β-1,4-glucanases have been classified into two subfamilies (Nicol et al., 1998). One subfamily consists of soluble secreted enzymes that contain an N-terminal signal peptide and EGase domain; these enzymes are located in the periplasm where they function as cell wall-softening enzymes that modify the cell wall. The other EGase subfamily consists of membrane-anchored proteins that have a predicted N-terminal transmembrane anchor motif (Brummell et al., 1997a). TaEG, like KOR and TomCel3, belongs to the latter subfamily and contains a transmembrane domain located between amino acids 74 to 96. The precise function of membrane-anchored EGases is currently unclear, but these enzymes are located in the plasma membrane and participate in cellulose metabolism in the inner layers of the cell wall (Brummell et al., 1997a; Nicol et al., 1998; Del Campillo, 1999; Molhoj et al., 2001). Some membrane-anchored EGases are involved in cell elongation. In tomato vegetative tissues the highest levels of TomCel3 mRNA were found in the most actively growing cells, in the expanding zones of young hypocotyls and in young expanding leaves (Brummell et al., 1997b). The Arabidopsis KOR gene has been identified with the dwarf mutant KORRIGAN and found to be involved in normal wall assembly and cell elongation (Nicol et al., 1998). In G. barbadense the Cel gene is involved in cotton fiber elongation (Zhu et al., 2011). Our phylogenetic analysis revealed that the TaEG genes clustered more closely with O. sativa OsGLU1. Furthermore, alignment analysis demonstrated that TaEG shared more identity with OsGLU1 (83%) than other membrane-anchored EGases. These findings suggest that TaEG is an ortholog of O. sativa OsGLU1 and may have similar biological roles. The O. sativa OsGLU1 gene has been identified with the dwarf mutant glu and found to be involved in cell elongation, cellulose and pectin content (Zhou et al., 2006).

Expression analysis showed that the highest levels of TaEG mRNA occurred in the 7–10 mm stage of CM28TP spikes. CM28TP has two more pistils per floret than CM28 and young spikes at the 7–10 mm stage in the primordial differentiation phase of subsidiary pistils (Yang et al., 2011). Based on these observations, we suggest that TaEG may contribute to pistil development and could be functionally important in defining the morphology of the three pistil mutant. However, this suggestion requires confirmation through additional experiments.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 30871533) and the Scientific Research Fund of Sichuan Provincial Education Department (grant no. 12ZB325).

Footnotes

Associate Editor: Houtan Noushmehr

References

- Beguin P. Molecular biology of cellulose degradation. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1990;44:219–248. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.44.100190.001251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beguin P, Aubert JP. The biological degradation of cellulose. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1994;13:25–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1994.tb00033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisaria VS, Mishra S. Regulatory aspects of cellulase biosynthesis and secretion. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 1989;9:61–103. doi: 10.3109/07388558909040616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brummell DA, Bird CR, Schuch W, Bennett AB. An endo-1,4-β-glucanase expressed at high levels in rapidly expanding tissues. Plant Mol Biol. 1997b;33:87–95. doi: 10.1023/a:1005733213856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brummell DA, Catala C, Lashbrook CC, Bennett AB. A membrane-anchored E-type endo-1,4-β-glucanase is localized on Golgi and plasma membranes of higher plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997a;94:4794–4799. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne KA, Lehnert SA, Johnson SE, Moore SS. Isolation of a cDNA encoding a putative cellulase in the red claw crayfish Cherax quadricarinatus. Gene. 1999;239:317–324. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00396-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoffersen RE, Tucker ML, Laties GG. Cellulase gene expression in repining avocado fruit: The accumulation of cellulase mRNA and proteins as demonstrated by cDNA hybridization and immunodetection. Plant Mol Biol. 1984;3:385–391. doi: 10.1007/BF00033386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Campillo E. Multiple endo-1,4-β-D-glucanase (cellulase) genes in Arabidopsis. Curr Top Dev Biol. 1999;46:39–61. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(08)60325-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo TR, Gill BS. The deletion stocks of common wheat. J Hered. 1996;87:295–307. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrarese L, Trainotti L, Moretto P, Polverino de Laureto P, Rascio N, Casadoro G. Differential ethylene-inducible expression of cellulase in pepper plants. Plant Mol Biol. 1995;29:735–747. doi: 10.1007/BF00041164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hama E, Takumi S, Ogihara Y, Murai K. Pistillody is caused by alterations to the class-B MADS-box gene expression pattern in alloplasmic wheats. Planta. 2004;218:712–720. doi: 10.1007/s00425-003-1157-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrissat B, Claeyssens M, Tomme P, Lemesle L, Mornon JP. Cellulase families revealed by hydrophobic cluster analysis. Gene. 1989;81:83–95. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90339-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemmerer EC, Tucker ML. Comparative study of cellulases associated with adventitious root initiation, apical buds, and leaf, flower and pod abscission zones in soybean. Plant Physiol. 1994;104:557–562. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.2.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane DR, Wiedemeier A, Peng L, Hofte H, Vernhettes S, Desprez T, Hocart CH, Birch RJ, Baskin TI, Burn JE, et al. Temperature-sensitive alleles of RSW2 link the KORRI-GAN endo-1,4-β-glucanase to cellulose synthesis and cytokinesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2001;126:278–288. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.1.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lashbrook CC, Gonzalez-Bosch C, Bennett AB. Two divergent endo-β-1,4-glucanase genes exhibit overlapping expression in ripening fruit and abscising flowers. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1485–1493. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.10.1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCt method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manickavelu A, Kambara K, Mishina K, Koba T. An efficient method for purifying high quality RNA from wheat pistils. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2007;54:254–258. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2006.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molhoj M, Jorgensen B, Ulvskov P, Borkhardt B. Two Arabidopsis thaliana genes, KOR2 and KOR3, which encode membrane-anchored endo-1,4-β-D-glucanases, are differentially expressed in developing leaf trichomes and their support cells. Plant Mol Biol. 2001;46:263–275. doi: 10.1023/a:1010688726755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicol F, His I, Jauneau A, Vernhettes S, Canut H, Hofte H. A plasma membrane-bound putative endo-1,4-β-D-glucanase is required for normal wall assembly and cell elongation in Arabidopsis. EMBO J. 1998;17:5563–5576. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.19.5563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng ZS. A new mutation in wheat producing three pistils in a floret. J Agro Crop Sci. 2003;189:270–272. [Google Scholar]

- Porebski S, Bailey LG, Baum BR. Modification of a CTAB DNA extraction protocol for plants containing high polysaccharide and polyphenol components. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 1997;1:8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Rosso MN, Favery B, Piotte C, Arthaud L, De Boer JM, Hussey RS, Bakker J, Baum TJ, Abad P. Isolation of a cDNA encoding a β-1,4-endoglucanase in the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita and expression analysis during plant parasitism. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1999;12:585–591. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1999.12.7.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sears ER. The aneuploids of common wheat. Mo Agric Exp Stn Res Bull. 1954;572:1–58. [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software ver. 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JE, Coupe SA, Picton S, Roberts JA. Characterization and accumulation pattern of an mRNA encoding an abscission-related β-1,4-glucanase from leaflets of Sambucus nigra. Plant Mol Biol. 1994;24:961–964. doi: 10.1007/BF00014449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker ML, Sexton R, Del Campillo E, Lewis LN. Bean abscission cellulase: Characterization of a cDNA clone and regulation of gene expression by ethylene and auxin. Plant Physiol. 1988;88:1257–1262. doi: 10.1104/pp.88.4.1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe H, Noda H, Tokuda G, Lo N. A cellulase gene of termite origin. Nature. 1998;394:330–331. doi: 10.1038/28527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K, Saraike T, Shitsukawa N, Hirabayashi C, Takumi S, Murai K. Class D and B sister MADS-box genes are associated with ectopic ovule formation in the pistil-like stamens of alloplasmic wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Plant Mol Biol. 2009;71:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s11103-009-9504-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang ZJ, Peng ZS, Wei SH, Yu Y, Cai P. Identification of differentially expressed genes in three pistils mutation in wheat using annealing control primer system. Gene. 2011;485:81–84. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang ZJ, Peng ZS, Zhou YH, Peng LJ, Wei SH. Evaluation on the genetic background of wheat near isogenic lines for three pistils character by SRAP markers. J Nucl Agri Sci. 2012;1:22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W, Takeda H, Liu XZ, Nakagawa N, Sakurai N, Huang J, Li YQ. A novel endo-1,4-β-glucanase gene (LlpCel1) is exclusively expressed in pollen and pollen tubes of Lilium longiflorum. Acta Bot Sin. 2004;46:142–147. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou HL, He SJ, Cao YR, Chen T, Du BX, Chu CC, Zhang JS, Chen SY. OsGLU1, a putative membrane-bound endo-1,4-β-D-glucanase from rice, affects plant internode elongation. Plant Mol Biol. 2006;60:137–151. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-2972-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu HY, Han XY, Lv JH, Zhao L, Xu XY, Zhang TZ, Guo WZ. Structure, expression differentiation and evolution of duplicated fiber developmental genes in Gossypium barbadense and G. hirsutum. BMC Plant Biol. 2011;11:40–54. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-11-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Internet Resources

- GenScan software. http://genes.mit.edu/GENSCAN.html (accessed November 7, 2012).

- ORF finder software. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gorf/gorf.html.

- Swiss-Prot/TrEMBL tool for calculating isoelectric point and molecular mass. http://www.expasy.org/tools/pi_tool.html (accessed November 7, 2012).

- SignalP 4.1 software for identifying signal peptide cleavage sites. http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/ (accessed November 7, 2012).

- SCOP software for detecting transmembrane helices. http://scop.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/scop/ (accessed November 7, 2012).