Abstract

Most religious congregations in the USA are involved with some type of social service activity, including health activities. However, relatively few formally engage with people with HIV, and many have reported barriers to introducing HIV prevention activities. We conducted a qualitative case study of HIV involvement among 14 urban congregations in Los Angeles County in 2007. In-depth qualitative interviews of lay leaders and clergy were analyzed for themes related to HIV and other health activities, including types of health issues addressed, types of activities conducted, how activities were organized, and the relationship between HIV and other health activities. We identified three primary models representing how congregations organized HIV and other health activities: (1) embedded (n = 7), where HIV activities were contained within other health activities; (2) parallel (n = 5), where HIV and other health activities occurred side by side and were organizationally distinct; (3) overlap (n = 2), where HIV and non-HIV health efforts were conducted by distinct groups, but shared some members and organization. We discuss implications of each model for initiating and sustaining HIV activities within urban congregations over time.

Keywords: HIV, Faith-based, Congregations, Organization, United States

Introduction

Religious organizations may have a unique opportunity to address HIV due to their wide social reach and access to institutional and community resources. National surveys have found that half of all adults attend religious services at least monthly.1,2 Furthermore, the history of congregations in addressing social issues has fueled growing interest by public health professionals and policymakers in the potential for congregations to promote health and reduce health disparities, including for HIV.3–6 A survey of US congregations found that 10 % of congregations engaged in formal health-related programs;7 however, one-third of congregations may have more informal groups dedicated to ‘physical healing’, such as offering prayers for the sick.1 In addition, a later wave of the same survey found that 82 % of congregations engaged in formal or informal social service activities,8 including providing food, housing, or clothing to people in need, or confronting public health issues such as homelessness, substance abuse, and domestic violence. Given the strong involvement of congregations in health-related activities, it is striking that only about 6 % of US congregations have programs or activities serving people living with HIV.9

Understanding more about the congregations that do sponsor activities related to HIV, and what enables them to do this work, is critical to promoting congregational HIV involvement. Studies have identified numerous barriers to addressing HIV in congregations, including stigma, discomfort talking about sex, and lack of resources.10–12 However, it is also important to understand factors that may serve to facilitate HIV involvement, including involvement in other health activities. Studies suggest that congregational decision-making processes and dynamics may be as or more important to understanding how health and HIV activities are initiated and by whom, above other oft-cited factors such as resource availability or ideological orientation.7,13

Despite mounting evidence on the importance of health and social service activities among US congregations, there is little information on whether or how congregational HIV activities are related to other health activities. Such data on the structure and process from which HIV and other health activities emerge may be important for understanding how these activities are initiated and sustained within congregations.

We therefore report findings on the range and organization of health activities among a sample of diverse congregations selected to represent a range of HIV activity (from little activity to high activity). These findings come from a larger study of urban congregations and HIV involvement based on a conceptual framework positing that congregational involvement in HIV will be related to norms and attitudes, resources, and organizational structure and processes. The primary purpose of this paper is to explore one aspect of this framework: how congregational HIV activities relate to other types of health activities, and whether their organization may be leveraged to address HIV in urban congregations. The paper examines the following specific research questions: among congregations involved in HIV issues (involvement ranging from very low to high activity), what types of other health issues and activities do they tend to engage in?

How does the organization and implementation of HIV activities relate, if at all, to the organization and implementation of other health activities?

Methods

Case Study Design

We chose a comparative case study design that allows in-depth exploration of congregational dynamics, incorporation of multiple sources of data and perspectives within congregations, and comparison of health (including HIV) activities across types of congregations, using a community-based participatory approach which has been described elsewhere.14

Congregational Sampling and Case Selection

Our study focused on the three geographic areas within Los Angeles County that are most highly affected by HIV, according to county health department surveillance data. We compiled a list of 80 congregations that were identified by our community experts and other local sources as having been involved in HIV activities in the three study areas and administered a brief telephone screening questionnaire (with a response rate of 88 %). Using the screening data in consultation with our community advisory board, we identified a purposive sample of 14 congregations to obtain variation on our principal outcome of interest (level and type of HIV activities) as well as factors that are known to influence the implementation of HIV and other types of health programs in congregations, such as racial and ethnic profile of the congregation, religious denomination, and congregational size and resources.12,15 Each congregation received an unrestricted financial contribution for participation in the study.

Data Collection

We collected data during multiple visits over a roughly 1-year period for each case congregation, mostly during 2007. Our methods included:

Qualitative, in-depth interviews with clergy and lay leaders, covering leaders’ background and experience, congregational involvement in health and HIV activities, denominational and congregational policies regarding HIV, homosexuality, and drug and alcohol use, leader and congregation attitudes, and community characteristics and collaborations

a congregational information form (most often completed by the pastor) with basic information about congregational membership, resources, and programs or ministries

observations of religious services, health and/or HIV-related activities, and the facility and neighborhood context

review of archival information about the congregation and its health and HIV activities

A total of 57 persons were interviewed across the 14 congregations (three to six per congregation), including at least one clergy and one lay leader at each. In-person interviews using a semi-structured protocol and typically lasting 1.5 h (range 1–4 h) were recorded digitally and supplemented with detailed manual notes. We used structured field note templates for the observations of religious services, health and HIV activities, and neighborhood context.

Within-Case Analysis

We created single case summaries that incorporated data from the various sources to give an overall picture of each congregation and its involvement in health and HIV, including the types of activities, how and when they started and ended, and what factors have facilitated and posed challenges to implementation. We then validated each case summary with congregational leaders.

Cross-Case Analysis

Qualitative Coding

We performed extensive coding of interview transcripts to identify prominent themes across the congregation cases. We used content coding procedures to mark quotations related to the major components of our conceptual framework and interview guides16–18 combined with an inductive approach to identify new themes and sub-themes that emerged from the data.19,20 Research team members worked in pairs using qualitative text management software21 to code the interview transcripts, periodically double-coding transcripts to maintain inter-rater reliability, resolve discrepancies, and confirm emergent themes by consensus. For this paper, we primarily analyzed themes related to non-HIV health activities, including types of health issues addressed, types of activities conducted, how activities are organized, and their relationship with HIV activities. We also utilized results from a previous analysis of HIV activities and related themes within the case congregations.22

Results

Range of Congregational Health Issues and Activities

Table 1 describes key characteristics of the congregations (n = 14) and interview participants (n = 57). Congregations varied in their level of HIV activity, with four congregations in the low activity category (activities are infrequent or not targeted specifically to HIV), four in the intermediate category (activities are more frequent than once a year and may target HIV, but tend to be extensions of the usual repertoire of congregational work like pastoral care and health fairs), and six congregations in the high activity category (activities are frequent, target HIV, and include multiple types of activities above and beyond the traditional efforts and offerings of religious congregations).

Table 1.

Congregation and interview participant characteristics

| Number | |

|---|---|

| Congregations (n = 14) | |

| Predominant race/ethnicitya | |

| African American | 6 |

| Latino | 4 |

| White | 2 |

| Mixed | 2 |

| Congregation sizeb | |

| Large (≥501 members) | 6 |

| Medium (151–500 members) | 5 |

| Small (≤150 members) | 3 |

| Denomination | |

| Catholic | 3 |

| Evangelical/Pentecostal/Non-denominational | 4 |

| Mainline Protestant | 4 |

| Baptist | 1 |

| Level of HIV activity | |

| High | 6 |

| Medium | 4 |

| Low | 4 |

| Interview participants (n = 57) | |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| African American | 22 |

| Latino | 15 |

| White | 18 |

| Asian | 1 |

| Other | 1 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 27 |

| Male | 30 |

| Role | |

| Clergy | 22 |

| Lay | 35 |

aRequires race/ethnicity to comprise ≥70 % of regular participants

bMeasured in terms of regularly attending congregational participants

The congregations in our case study sample engaged in a wide range of health issues via a diverse set of health activities. Health issues spanned physical and mental health conditions but also other issues reflective of comprehensive definitions of public health, including attention to basic needs (e.g., food, clothing, housing, etc.) and community health concerns such as violence. Table 2 presents the numbers of congregations in our study that engaged in different types of health issues. All the congregations in our sample addressed HIV to some degree (from low—e.g., clergy attending a training workshop on HIV—to high—e.g., long-standing HIV ministry with robust portfolio of activities). Almost all the congregations addressed health issues related to HIV risk, including sexual health and behavior, and substance abuse.

Table 2.

Range of health issues addressed by case study congregations

| Health issue | No. of congregations (n = 14) |

|---|---|

| Physical health | 14 |

| HIV | 14 |

| Other chronic illnesses | 14 |

| General physical healtha | 14 |

| Sexual health, not including HIV | 13 |

| Healthy lifestyles (nutrition, exercise, etc.) | 10 |

| Malnutrition and food insecurity | 10 |

| Substance use | 13 |

| Mental health | 12 |

| Life events and transitions (e.g., aging, parenting) | 11 |

| Violence (e.g., gangs, domestic violence) | 9 |

| Homelessness | 7 |

| International health | 5 |

| Disaster relief | 3 |

aIncludes attention to acute episodes of illness (e.g., caring for the sick), issues of primary or preventive care, or peer health training (e.g., CPR)

Congregations addressed health issues through a wide range of activities (Table 3), which we classified into three categories—prevention and education, care and support, and awareness and advocacy—based on our previous analysis of HIV activities.22 For comparison, Table 3 presents the number of congregations conducting each type of activity for HIV versus other health issues. The first two types of activities (prevention and education, and care and support) were very common for both HIV and other health activities. Overall, few congregations conducted health activities focused on awareness and advocacy, although these were more common for HIV.

Table 3.

Range of health activities conducted by case study congregations

| No. of congregations (n = 14) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Prevention and education | HIV activities | Other health activities |

| Hosting workshops, seminars, or classes | 9 | 14 |

| Testing and screening | 7 | 11 |

| Providing health information and educational materials | 9 | 10 |

| Health fair | 7 | 10 |

| Behavior modification activities (e.g., walking group) | n/a | 7 |

| Health promotion from the pulpit | 0 | 4 |

| Vaccinations/immunizations | n/a | 3 |

| Participation in external workshops | 5 | 1 |

| Formally assessing health needs | n/a | 1 |

| Care and support | ||

| Pastoral care and social support for the sick | 11 | 14 |

| Material support (e.g., food, clothing) | 7 | 11 |

| Support groups | 4 | 8 |

| Referrals to medical services | 6 | 7 |

| Support of external care and support organizations | 8 | 6 |

| Providing direct services (e.g., clinic, recovery program) | 0 | 5 |

| Informal/peer 1-on-1 counseling (e.g., substance abuse) | 0 | 4 |

| CPR/first aid training | n/a | 3 |

| Retreats for people affected by a health issue | 1 | 1 |

| Awareness and advocacy | ||

| Public advocacy | 5 | 5 |

| Participation in “walks”, marches, or parades | 7 | 4 |

| Raising awareness from the pulpit | 10 | 3 |

| Stigma reduction | 6 | 1 |

| Worship services related to health | 6 | 1 |

n/a not applicable

Results for HIV activities from previous publication, see Derose et al (2011)22

No discernible patterns in health issues or health activities conducted by congregations emerged by HIV activity level. Congregations with low, medium, and high HIV activity were all engaged in a varied range of health issues and activities.

Organization of Congregational HIV and Other Health Activities

Our congregational case studies also had diverse approaches to organizing and implementing health activities, and to how HIV and other health activities were organized with respect to one another. These approaches appeared to vary according to three broad features: (1) whether the congregation had an overarching organizing body or bodies (e.g., ministry, committee, etc.) under which HIV and other health activities were planned and implemented, (2) whether existing overarching organizing bodies were health versus non-health specific (e.g., health ministry vs. a men’s group), and (3) the degree of centralization of leadership for HIV and other health activities within the congregation (e.g., one overall health ministry vs. many smaller issue-based committees; a key leader vs. diffuse leadership).

Examining these features individually, first we found that all 14 congregations had some type of overarching organizing body or bodies under which HIV and other health activities were usually (but not always) organized and implemented. The majority of these organizational bodies were health-related, such as parish nursing programs or substance abuse ministries; the rest were not specifically related to health, such as social service committees, social justice committees, or gay and lesbian ministries. Second, only two congregations had HIV-specific overarching ministries. Finally, despite the presence of overarching organizational bodies, the majority of congregations had diffused approaches to planning and implementing HIV and other health activities. For example, while all congregations had overarching organizational bodies generally responsible for health activities, other sub-committees or groups within the congregations often conducted individual health activities, according to the specific experiences or priorities of lay leaders or members.

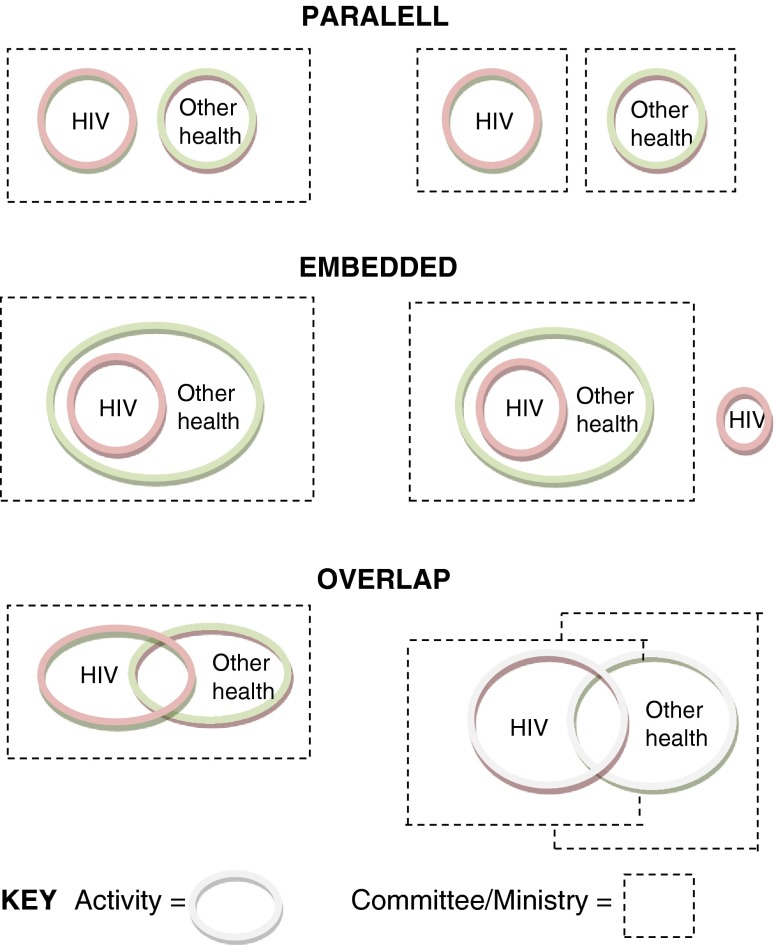

Examining combinations of these features, we found three general organizational models for how HIV and non-HIV health activities were related within our case congregations: parallel, embedded, and overlap models (see Figure 1). Congregations with high levels of HIV activity (six cases) tended to exhibit the overlapping (two cases) and parallel models (three cases) of organizing health and HIV activities organization. The embedded models were mostly represented by low or medium activity congregations, except for one high activity congregation which also utilized this model. Below we provide examples from our case studies to illustrate each general model and particular variations.

Figure 1.

Models of organizing HIV and other health activities in case study congregations.

Parallel Model

In parallel models (five congregations), HIV and non-HIV health activities primarily occurred side by side and were clearly distinct from one another in terms of their content, timing, implementation, and individuals involved. However, there was variation among these congregations as to whether HIV and non-HIV health activities were grouped under the same or separate overarching organizational bodies.

Examples of Parallel Model

One example of a congregation organized under the parallel model with shared overarching organization was a small, racially diverse (no predominant race or ethnicity) non-denominational Christian church with high HIV activity. This congregation had been active in HIV since the mid-1990s, starting in response to community need perceived by the pastor and an overall commitment to social justice. The congregation had no formal AIDS ministry, but had developed a strong set of self-contained HIV activities (e.g., a food and toiletries pantry specifically for people living with HIV) that operated side by side with other health activities in the congregation (e.g., healthy eating and nutrition), led by lay leaders dedicated to their specific causes. All of these activities fell generally under the umbrella of the congregation’s social service ministry, which broadly attended to social needs within and external to the congregation.

Meanwhile, an example of a congregation organized under the parallel model with separate overarching organization was a large, primarily Latino, Roman Catholic church with long-standing involvement in HIV issues dating to relatively early in the epidemic in Los Angeles. In this congregation, HIV activities were largely organized by the parish’s gay and lesbian ministry with many English-speaking members. In contrast, other health activities (e.g., primary care, health fairs) were within the purview of the congregation’s parish nursing program, which generally did not address HIV except for referrals on a case by case basis. The parish nursing program served all congregants, but was especially important to Spanish-speaking and other immigrants with limited access to other sources of care. One clergy member from this congregation noted how involvement with HIV was separate from the parish nursing program,

“[Getting involved with HIV] wasn’t because of that [parish nursing] program, the one I mentioned before having to do with blood pressure, vaccines and all that…it was [because of ]someone else who works at the hospital in the adult education department. But they were both from [the same] hospital. ”

Embedded Model

In embedded models—the most prevalent in our study sample (seven congregations)—most HIV activities were fully contained within other health activities that had a primary focus other than HIV (e.g., sexual health in general, substance abuse, etc.). These activities were in turn embedded within an overarching body, which were almost all health related.

Examples of Embedded Model

An example of the standard embedded model was a medium-sized, non-denominational evangelical Christian church with a primarily Latino congregation and low HIV activity. While this congregation had very little HIV activity overall, it had a long-standing and ongoing commitment to addressing issues of substance abuse and violence affecting both congregants and the wider community. In activities to address substance abuse and other community issues, some HIV involvement had occurred, such as inviting a local non-profit group working on HIV to be part of their health fair. However, these HIV activities had no dedicated implementing group within the congregation, nor any clear overarching organization. Rather, they were embedded within other health efforts, which themselves had strong overarching organization. A clergy member at this congregation described that discussions about HIV prevention would happen within the context of discussions of abstinence in general: “But we try to work [with the youth] and we teach them not to get involved in any sexual activities….we have group sessions for them and they talked about…abstaining from sex…talked about dating....talked about HIV.”

Overlap Model

In this model, HIV and non-HIV health efforts were conducted by distinct, independent groups, but overlapped in interactions among members and overarching organization. It was the least common model in our case sample (two congregations).

Examples of Overlap Model

Each of the two congregations exhibiting the overlap model had slightly different sub-structures. The first congregation was a medium sized, Jewish (Reform movement) synagogue, with mostly White members and high HIV activity. The congregation had a strong overall social justice orientation, and had been involved with HIV since the early 1990s with the instrumental leadership of the rabbi. The types and intensity of involvement changed over time from confronting the immediate crisis of HIV to focus more on social activities and community service, a shift mirroring changes in the HIV epidemic due to the advent of effective HIV treatment. In this congregation, both HIV and other health activities were organized by various people across diverse health and non-health groups or committees within the congregation, but with oversight by a central social action committee.

Because of the shared overarching organization, there tended to be more fluidity between HIV and other health activities, which frequently overlapped in terms of events and spaces. One lay leader explained how activities overlap under the umbrella of the social action committee:

“[The food pantry activity] is what most of the members of the social action committee do…And then there’s some projects that operate under the umbrella of the social action committee but aren’t really part of it, like staffing the water station at AIDS Walk….And to a degree, [the soup kitchen activity for people living with HIV] is in the same basket. It is officially a project of [the] social action [committee] but it’s really just my involvement that keeps it going.”

The second congregation exhibiting an overlap model was a large Catholic church with primarily African American members and high HIV activity. This congregation, too, had been involved in HIV since the late 1980s/early 1990s, driven by strong lay leadership. Although there had been ebbs and flows in HIV involvement over time, an extensive set of HIV activities were organized under an AIDS Ministry. At the same time, the congregation also had strong involvement in non-HIV health issues via a separate set of activities organized under other health-related ministries. Occasionally, HIV and other health activities overlapped for specific events or programs, such as a health fair.

Discussion

In this study, congregations engaged in a wide variety of health issues and activities, including HIV. However, they varied in how HIV and other health activities were related in terms of both implementation and overarching organization, even among congregations with similar levels of HIV activity. While health activities have been increasingly documented in religious congregations, few studies have explored how HIV and other health activities are organized with respect to one another, and how other health activities may inform the development of HIV activities (or vice versa). Recent analyses found that congregations with organizational structures oriented towards community needs were significantly more likely to provide programs or activities for people living with HIV,9,13 pointing to the importance of examining organizational facilitators. However, these studies did not explore how health-specific organization structures affected HIV involvement.

We identified three primary models representing how our case study congregations organized HIV and non-HIV health activities in relation to one another: the parallel model, the overlap model, and the embedded model. The key difference among the three models was the extent to which HIV and non-HIV health activities had distinct activity space, time, people (staff, volunteers, and/or participants), and content.

The embedded model was the most common model among our case study congregations, representing a diverse set of congregations across levels of HIV activity. This model is most congruent with results of previous quantitative research exploring general congregational health activities that found sponsorship of non-health-related social service programs to be a significant predictor of involvement in health activities.7 This could be due to both the prior existence of program infrastructure, lessons learned about program development and administration, and the ability to mobilize resources. Thus, congregations implementing HIV activities in an embedded model might be able to leverage existing health activities to incorporate HIV activities without having to devote excessive additional resources (whether financial or human). In addition, it is possible that the ability to introduce HIV-related topics into a setting where they could be easily contextualized within other issues already important to the congregation (e.g., talking about substance abuse, workshops on youth sexual behavior, etc.) could have eased their introduction and increased the sustainability of HIV involvement, particularly in the face of stigma.23 The fact that we see a range of HIV activity levels within this model suggests that it may be a sustainable model for congregations not only to initiate, but grow, HIV activities.

The parallel model had a clear boundary between HIV and non-HIV activities—but no integration—and was also common among our case study congregations. In larger congregations, the isolating effect of this separation appeared particularly striking, where two distinct groups conducting health activities—one focused on HIV and one on other health issues—could operate within the same context and truly have little interaction or buy-in from the other’s participants. On the other hand, parallel divisions between HIV and other health activities in small congregations did not appear to produce such isolation between activities, given the tighter social networks and natural interdependence characterizing these congregations. Both the large and small examples of the parallel model imply that in some cases, if existing health-related programs within the congregation are not receptive or able to address HIV for either ideological or logistical reasons, it may be more feasible for congregants with particular interest in HIV issues to organize activities as a separate program.

Of all of the models, the overlap model represented the most integration between HIV and non-HIV health activities, yet was the least common among our study congregations. In this model, each realm of activity had a clear and visible boundary with accompanying attention and commitment, yet there was also interaction between the activities, at times sharing both people and resources. It is thus not surprising that both of the two congregations that fell under this model were high HIV activity congregations.

Our study is subject to several limitations. First, generalizability is limited given our purposive sampling of congregations from one urban setting. Our sample congregations were chosen to vary across faith tradition, size, race-ethnicity, and level of HIV activity, including congregations with at least minimal involvement in HIV issues, making it well suited to describe the variety and salience—but not the overall prevalence—of congregational HIV activities and organization. In addition, our reliance on qualitative interview data rather than more quantitative methods for identifying organizational structures and processes allowed us to identify and flesh out models of organizing congregational health and HIV activities, but not to systematically analyze the predictors and consequences of these models across congregations.

Understanding the organization of existing congregational health activities may help potential public health partners appreciate the role that urban congregations play in community health as well as how this capacity could be leveraged to address a variety of health issues. Specifically, our findings suggest that embedding HIV activities within other health activities may provide a natural context for HIV activities to take advantage of pre-existing buy-in to a broader health issue, whether it be substance abuse or health education for youth. This may serve to not only introduce HIV activities, but also help sustain them over time. For congregations whose existing health programs may not be as supportive to addressing HIV, a parallel model with a separate programmatic structure may be more feasible to organize congregational HIV activities. Whether it is possible—or desirable—for either embedded or parallel models to evolve into more integrated overlap models may depend on the longevity of HIV activities as well as congregational context, dynamics, and culture.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the members of the study’s Community Advisory Board who have provided much-valued guidance and counsel throughout the study, in particular the Rev. Dr. Clyde W. Oden, the Rev. Michael Mata, Delis Alejandro, Deborah Owens Collins, Keesha Johnson, Mario Pérez, the Rev. Chris Ponnet, the Rt. Rev. Chester Talton, and Richard Zaldivar. We also thank the 14 case study congregations and their leaders, who for confidentiality reasons, are not named. Finally, we thank our colleagues at RAND who helped conceptualize and/or carry out the overall study, especially David Kanouse, Ricky Bluthenthal, Laura Werber, Blanca Domínguez, and Jennifer Hawes-Dawson

This paper was supported by Grant Numbers 1R01 HD050150 (PI: Derose) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and T32HS00046 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NICHD or AHRQ. Analysis and writing for this paper were conducted by KP primarily while at the Pardee RAND Graduate School.

References

- 1.Chaves M. Congregations in America: Harvard Univ Press; 2004.

- 2.Idler EL, Musick MA, Ellison CG, et al. Measuring multiple dimensions of religion and spirituality for health research. Research Aging. 2003;25(4):327. doi: 10.1177/0164027503025004001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haugk KC. Unique contributions of churches and clergy to community mental health. J Comm Ment Health. Spring 1976; 12(1): 20–28. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Koenig HG. Health care and faith communities. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(11):962–963. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.30902.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lasater TM, Wells BL, Carleton RA, Elder JP. The role of churches in disease prevention research studies. Public Health Rep. 1986;101(2):125–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olson LM, Reis J, Murphy L, Gehm JH. The religious community as a partner in health care. J Community Health. Winter 1988; 13(4): 249–257. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Trinitapoli J, Ellison CG, Boardman JD. US religious congregations and the sponsorship of health-related programs. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(12):2231–2239. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaves M, Anderson SL. Continuity and change in American Congregations: introducing the second wave of the national congregations study*. Sociol Relig. 2008;69(4):415. doi: 10.1093/socrel/69.4.415. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frenk SM, Trinitapoli J. US Congregations’ Provision of Programs or Activities for People Living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS and Behavior. 2012:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Hernández EI, Burwell R, Smith J. Answering the call: how Latino churches can respond to the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Philadelphia: Esperanza;2007.

- 11.Smith J, Simmons E, Mayer KH. HIV/AIDS and the Black Church: what are the barriers to prevention services? J National Medical Assoc. Dec 2005; 97(12): 1682–1685. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Tesoriero JM, Parisi DM, Sampson S, Foster J, Klein S, Ellemberg C. Faith communities and HIV/AIDS prevention in New York State: results of a statewide survey. Public Health Rep. 2000;115(6):544–556. doi: 10.1093/phr/115.6.544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fulton BR. Black Churches and HIV/AIDS: factors influencing congregations’ responsiveness to social issues. J Scien Study Religion. 2011;50(3):617–630. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5906.2011.01579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Derose KP, Mendel PJ, Kanouse DE, et al. Learning about urban congregations and HIV/AIDS: community-based foundations for developing congregational health interventions. Journal of Urban Health. 2010:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Thomas SB, Quinn SC, Billingsley A, Caldwell C. The characteristics of northern Black churches with community health outreach programs. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(4):575. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.84.4.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weber RP. Basic content analysis. 2. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Altheide D. Qualitative media analysis. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krippendorff K. Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology. 2. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA; 1994.

- 20.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: grounded theoryprocedures and techniques. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atlas.ti [computer program]. [computer program]. Version 5.2. Berlin: Scientific Software Development GmbH; 2006.

- 22.Derose KP, Mendel PJ, Palar K, et al. Religious congregations' involvement in HIV: a case study approach. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(6):12. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9827-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bluthenthal RN, Palar K, Mendel P, et al. Attitudes and beliefs related to HIV/AIDS in urban religious congregations: barriers and opportunities for HIV-related interventions. Social Science & Medicine. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]