Background: Current antioxidant therapies do not directly target lipid peroxidation products.

Results: Pyridoxamine treatment scavenges lipid peroxides in mouse retina, as exemplified by isolevuglandins, and improves retinal mitochondrial morphology after animal exposure to bright light.

Conclusion: Pyridoxamine reduces deleterious effects of lipid peroxidation in the retina.

Significance: Pyridoxamine supplementation should be considered for inclusion in antioxidant vitamin formulations.

Keywords: Lipid Peroxidation, Mass Spectrometry (MS), Mitochondria, Oxidative Stress, Retinal Degeneration, Age-related Macular Degeneration, Isolevuglandin, Pyridoxamine, Vitamin B6

Abstract

The benefits of antioxidant therapy for treating age-related macular degeneration, a devastating retinal disease, are limited. Perhaps species other than reactive oxygen intermediates should be considered as therapeutic targets. These could be lipid peroxidation products, including isolevuglandins (isoLGs), prototypical and extraordinarily reactive γ-ketoaldehydes that avidly bind to proteins, phospholipids, and DNA and modulate the properties of these biomolecules. We found isoLG adducts in aged human retina but not in the retina of mice kept under dim lighting. Hence, to test whether scavenging of isoLGs could complement or supplant antioxidant therapy, we exposed mice to bright light and found that this insult leads to retinal isoLG-adduct formation. We then pretreated mice with pyridoxamine, a B6 vitamer and efficient scavenger of γ-ketoaldehydes, and found that the levels of retinal isoLG adducts are decreased, and morphological changes in photoreceptor mitochondria are not as pronounced as in untreated animals. Our study demonstrates that preventing the damage to biomolecules by lipid peroxidation products, a novel concept in vision research, is a viable strategy to combat oxidative stress in the retina.

Introduction

The body's ability to cope with reactive oxygen intermediates declines with age. This leads to increased oxidative stress and endogenous lipid peroxidation occurring in many common diseases associated with aging: cardiovascular disease (1–3), Alzheimer disease (4–6), Parkinson disease (7, 8), and age-related macular degeneration (AMD)3 (9–12). Of the many lipids affected by peroxidation, long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids are extraordinarily susceptible to this oxidative process (13), which results in the formation of aldehydes such as malondialdehyde (14), 4-hydroxynonenal (14), hydroxy-ω-oxoalkenoic acids (15), and the extremely reactive γ-ketoaldehydes (16–19). The latter are represented by isolevuglandins (isoLGs) formed from arachidonate (17, 20) and docosahexaenoate (21). These lipid peroxidation products interact with biomolecules and may alter their function. When attached to proteins (18, 22), lipid peroxidation products are associated with reduced activity of metabolically important enzymes (23–28) and, in some cases, trigger an immune response (12, 14). When attached to phospholipid (PhosL) headgroups (29–31) and DNA (32, 33), lipid peroxidation products can make the latter cytotoxic (30, 31, 34) and the former genotoxic (34). Modifications produced by lipid peroxidation products are also used as biomarkers of oxidative stress (35).

General antioxidant therapies utilizing nutritional supplements, e.g. vitamins E and C and β-carotene, have shown only low to moderate success in preventing cardiovascular events (36, 37), decreasing the risk of developing Alzheimer disease (38), and preventing the progression of intermediate to severe forms of AMD (39, 40). This suggests that the first step in the oxidative injury cascade, i.e. the production of reactive oxygen intermediates (Fig. 1), is not sufficiently blocked. Perhaps attention should focus on the downstream steps in this cascade, namely scavenging of the lipid peroxidation products as they are formed, before they bind and damage biomolecules. Accordingly, pharmacological interventions to prevent interactions of the lipid peroxidation products with biomolecules could be a complementary or alternative therapy for treating diseases associated with lipid peroxidation. A prime candidate disease for such treatment is AMD, affecting the retina, an organ with a highly oxidative environment (41) and enriched with polyunsaturated fatty acids such as docosahexaenoic and arachidonic acids (42). Indeed, in AMD, a major cause of irreversible vision loss (43), carboxyethyl pyrroles produced from protein modification by docosahexaenoate-derived γ-ketoalkenal phospholipids are elevated in the subretinal space (44) and have a pathological role in the disease etiology (10). Furthermore, isoLG-modified PhosLs are present at increased amounts in patients' serum (30), and isoLGs were confirmed to modify protein(s) in AMD-afflicted human retina (24). Scavenging of isoLGs could be of particular importance because they react more avidly than malondialdehyde, 4-hydroxynonenal, and hydroxy-ω-oxoalkenoic acids, rapidly forming irreversible pyrrole-derived adducts (18, 19, 45).

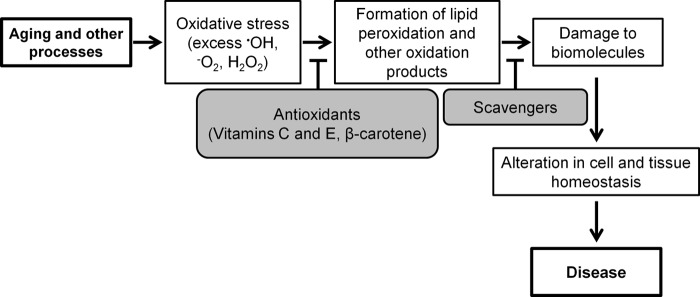

FIGURE 1.

Oxidative injury cascade. The aging process reduces antioxidant capacity, leading to oxidative stress. The consequences of this include, among other oxidized species, formation of lipid peroxidation products that can damage biomolecules like proteins, phospholipids, and DNA, eventually contributing to disease. Therapies with general antioxidants focus on reducing the levels of reactive oxygen intermediates. Treatment with scavengers such as PM, however, aims to reduce the levels of downstream oxidation products.

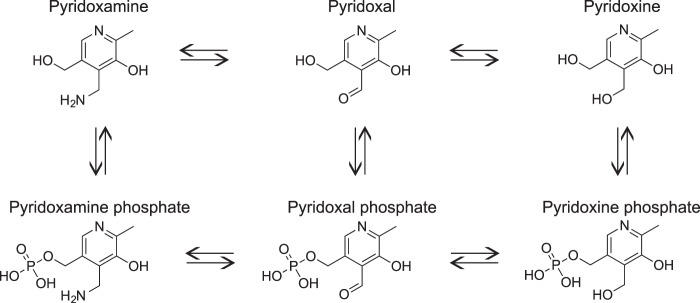

Pyridoxamine (PM) is a B6 vitamer along with five other related compounds: pyridoxal (PL), pyridoxine, pyridoxamine phosphate, pyridoxal phosphate (PLP), and pyridoxine phosphate (Fig. 2). PM and its phosphorylated form are the only B6 vitamers that have a primary amino group and hence can form stable pyrrole-derived conjugates with isoLGs. PM interacts with isoLGs 2000-fold faster than the ϵ-amino groups of protein lysyl residues, making PM an efficient scavenger of this type of lipid peroxidation products (46). Treatment with PM and its analogs has been shown to prevent H2O2-mediated cytotoxicity and decreased isoLG-protein adduct formation in cell culture (26, 47, 48). The PM analog salicylamine was also shown to lower the isoLG modification of proteins and improve working memory in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease (49). Not only does PM scavenge lipid peroxidation products, but it also reduces levels of advanced glycation end products as indicated by studies on rats that showed amelioration of pathologies associated with diabetic nephropathy and retinopathy (50, 51). PM was even evaluated in humans in phase I and II clinical trials (under the name Pyridorin) for treatment of type 2 diabetic nephropathy (52, 53).

FIGURE 2.

Structures and enzymatic interconversion of the six B6 vitamers. Pyridoxamine along with pyridoxal and pyridoxine are the three natural forms of vitamin B6 that are converted in mammals into the single biologically active form, pyridoxal phosphate, serving as a prosthetic group for a wide variety of enzymatic reactions (99, 100).

Despite the encouraging data on the therapeutic properties of PM in other studies (26, 46–48), pharmacological interventions with this compound aimed at scavenging lipid peroxidation products, including γ-ketoaldehydes, have not been pursued in the vision field. Hence, herein, we investigated whether the effects of isoLGs in the retina could be lowered or prevented by treatment with PM. We developed an animal model to study isoLG adduction in this organ; we showed that PM penetrates the blood-retina barrier and reaches the retina; and we identified structures in the retina affected by isoLG adduction. We also developed a quantitative mass spectrometry (MS) assay for the measurements of the protein modification by isoLGs in retinal tissue and showed that treatment with PM followed by exposure to bright light decreases retinal isoLG adduction and lessens light-induced retinal pathologies.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Authentic iso[4]levuglandin E2 (iso[4]LGE2) was synthesized as described and assayed by NMR (54). The N-tert-butoxycarbonyl pentadecapeptide VVLAPETGELKSVAR480, based on the CYP27A1 Lys476-containing tryptic peptide, was custom-synthesized by American Peptide Co., Inc. (Sunnyvale, CA). Synthesis and characterization of [2H6]iso[4]LGE2 and preparation and purification of the VVLAPETGELK-(iso[4]LGE2 lactam)-SVAR480 and VVLAPETGELK-([2H6]iso[4]LGE2 lactam)-SVAR480 internal standard (d6-Std) will be published elsewhere. Apis mellifera venom phospholipase A2 (PLA2) and [2H3]methyl-PM (d3-PM) were purchased from Sigma. Aminopeptidase M and Pronase were from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA).

Ethics Statement

Human retina sections were generously provided by Dr. Christine Curcio of the University of Alabama Birmingham, where the use of human tissues was approved by an institutional review board, and the protocols adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and the National Institutes of Health Belmont Report. Retina sections were from de-identified human donors and were obtained with the written informed consent of the respective families. All animal-handling procedures and experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Case Western Reserve University.

Animals

Pigmented B6129SF2/J strain female mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Mice were housed in the Animal Resource Center at Case Western Reserve University and maintained in a standard 12-h light (∼10 lux)/12-h dark cycle environment. Water and food were provided ad libitum. Mice were 6–9 months old.

PM Administration

PM was dissolved in drinking water (1 g/liter), which was placed in light-protected bottles. This water was provided ad libitum. The average oral dose of PM was 25 mg/kg/day assuming that daily water consumption was 10 ml/mouse (55). No signs of toxicity were evident in PM-treated mice for the duration of experiments (up to 9 days of treatment) as assessed by lack of mortality, hunched posture, lethargy, fur ruffling, or respiratory distress.

Exposure to Bright Light

The procedure was as described previously (56). Prior to exposure, 1% tropicamide eye drops were instilled bilaterally to dilate pupils. Light output was from a 42-watt compact fluorescent spiral bulb (General Electric) that was calibrated by a Digiflash light meter (Gossen, Germany). The illumination was 10,000 lux for 2 h, initiated consistently at 9:30 a.m. DietGel (ClearH2O) was provided for animal hydration during exposure to bright light. Following exposure, mice were returned to the normal enclosures and maintained on either PM-supplemented or regular drinking water depending on the treatment paradigm.

Optimization of Mass Spectrometry Parameters for Analysis of B6 Vitamers in Mouse Tissues

Aqueous solutions of 20 μm PM, d3-PM, pyridoxine, PL, and PLP in 650 mm acetic acid were infused individually at a rate of 10 μl/min directly into the electrospray ionization source of the hybrid triple quadrupole/linear ion trap mass spectrometer (4000 QTrap, AB SCIEX) operating in the positive ionization mode. The following parameters for the electrospray source were used: an ion spray voltage of 5500 V; curtain gas of 13 p.s.i.; ion source gas of 30 p.s.i.; heater gas of 60 p.s.i., and interface heating temperature of 200 °C. MS2 scans were collected by the third quadrupole operating in resolving quadrupole mode with a scan time of 5 s. Collision-induced dissociation generated a single fragment ion for each analyte, consistent with previous studies (57) and in agreement with the published values (57). Hence, only one transition was used to quantify each B6 vitamer (m/z 169→134 for PM; m/z 172→137 for d3-PM; m/z 168→150 for PL; m/z 170→134 for pyridoxine, and m/z 248→150 for PLP). Yet the collision parameters were optimized for a maximal signal-to-noise ratio. Declustering potential (V), entrance potential (V), collision energy (eV), and cell exit potential (V) were: 40 and 10 V, 31 eV, and 8 V for PM and d3-PM; 39 and 9 V, 20 eV, and 10 V for PL; 46 and 10 V, 31 eV, and 8 V for pyridoxine; and 71 and 10 V, 24 eV, and 10 V for PLP. Authentic standards for pyridoxamine phosphate and pyridoxine phosphate were not commercially available. Therefore, the reported transitions (57) were used for these compounds with the collision parameters identical to those for PLP.

Quantification of B6 Vitamer Levels in Mouse Serum and Retina

Animals were terminally anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection with a mixture of ketamine (320 mg/kg) and xylazine (60 mg/kg). Blood was obtained by cardiac puncture and allowed to clot for 20 min at room temperature followed by centrifugation at 2500 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. The resulting supernatant (serum) was transferred to a light-protected microcentrifuge tube, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C. Following cardiac puncture, animals were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. Eyes were enucleated, and each retina was isolated, dipped twice for 1 s in cold 25 mm NH4HCO3, and placed in a light-protected microcentrifuge tube. The tube was frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. For B6 vitamer analysis, 100 μl of serum (average of 4.5 mg of total protein) or a single retina (average 250 μg of total protein) were supplemented with 50 pmol of d3-PM in 100 μl of cold, freshly prepared 5% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid in water. Serum was vortexed for 5 s, whereas the retina was homogenized by sonication (10% power with three 10-s continuous pulses) with a Digital Sonifier S-450D (Branson Ultrasonics) on ice. The serum and retinal samples were then centrifuged at 20,800 × g for 20 min at 4 °C to pellet the trichloroacetic acid-precipitated protein. The resultant protein-free supernatant was transferred to a light-protected autosampler vial for analysis by MRM. Samples were kept at 4 °C in the autosampler. An Ultimate 3000 liquid chromatography system (Dionex) equipped with a Zorbax SB-AQ column (2.1 × 100 mm, 3.5 μm, Agilent) with matching guard column (2.1 × 12.5 mm, 5 μm) was used for separation. Column temperature was maintained at 25 °C, and the injection volume was 20 μl. The liquid chromatography gradient was described previously (57). Briefly, initial chromatographic conditions were 99% solvent A (650 mm acetic acid containing 0.01% heptafluorobutyric acid) and 1% solvent B (acetonitrile). Analytes were eluted with a linear gradient from 1 to 20% of solvent B over 18 min at a flow rate of 150 μl/min. The column effluent was directed into the electrospray ionization source of the 4000 QTrap operating in the positive ionization mode. MRM chromatograms for PM, d3-PM, pyridoxine, PL, pyridoxamine phosphate, pyridoxine phosphate, and PLP were acquired using the optimized parameters. To quantify the B6 vitamers, a calibration plot for each vitamer was generated using 50 pmol of d3-PM with varying concentrations of PM, PL, PLP, and pyridoxine in a matrix of untreated mouse serum. The data obtained were fit using linear regression, and the concentration of each B6 vitamer was calculated according to its respective equation.

Quantification of Total Lys-iso[4]LGE2 Lactam Adducts in Mouse Retina

This was as described (58). Briefly, four retinas from three mice (1 mg of total protein) from each group were pooled, homogenized by sonication in 100 μl of 25 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, containing 10 mm CaCl2, 100 mm KCl, 100 μg/ml butylated hydroxytoluene, and 0.02% Triton X-100 (PLA2 digest buffer). PLA2 (800 units from a 10,000 units/ml stock) was added to the homogenate that was incubated overnight at 37 °C with shaking. The following morning, samples were supplemented with 1% SDS, heated to 90 °C for 5 min, and allowed to cool. Samples were then sequentially mixed with 4 volumes of methanol, 1 volume of chloroform, and 3 volumes of water to form the disc of precipitated protein at the interface between the aqueous and organic phases (59). The protein disk was isolated, washed sequentially with 200 μl of heptane and water, and then air-dried for 5 min. The pellet was supplemented with 5 pmol of d6-Std in 150 μl of 25 mm NH4HCO3 containing 10 mm CaCl2 and disrupted by sonication. The suspension was digested with 0.4 μg of Pronase (1:2.5 mg of protease/mg of total protein) at 37 °C for 24 h and then with 0.0052 units of aminopeptidase M (1:15 units of protease/mg of total protein) at 37 °C for 18 h. The digest was centrifuged at 17,000 × g for 10 min to precipitate undigested protein and insoluble material. The supernatant was transferred to a new microcentrifuge tube and evaporated to dryness in a Savant SC210A SpeedVac concentrator (Thermo Scientific). Samples were stored at −80 °C and dissolved in 50 μl of 5% acetonitrile in water containing 0.1% formic acid when analyzed. The MRM analysis was as described (58) using the d6-Std peptide internal standard and the following MRM transitions: m/z 479→84 and m/z 479→332 for Lys-iso[4]LGE2, and m/z 485→84 and m/z 485→338 for Lys-[2H6]-iso[4]LGE2. The extent of Lys-isoLG adduction in the samples was then calculated according to Equation 1,

where A represents the integrated peak areas and 0.732 is the coefficient obtained from the calibration curve.

Fluorescent Microscopy

Enucleated mouse eyes were marked to preserve orientation, and eyecups were prepared by removing the cornea, lens, and vitreous body followed by fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences) in 0.1 m potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. Transverse cryosections (5 μm thick) of the central retina were prepared as described (60). Slides were equilibrated to room temperature for 20 min, rinsed in PBS twice, and incubated in PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100 for 20 min. For immunostaining with antibodies against iso[4]LGE2 adducts (19), PLA2 hydrolysis of the tissue sections was performed to cleave the carboxylate ester and increase immunoreactivity. The PLA2 hydrolysis procedure was modeled after the method for cholesterol esterase treatment of cryosections (61). The PLA2 treatment time was maximal (1 h, longer incubation times negatively affect cryosection morphology), and the amount of PLA2 used was large (30 units), sufficient to hydrolyze ∼1 g of phospholipids in 1 h assuming maximal enzyme activity. The PLA2 digest buffer was the same as in the quantification of total Lys-iso[4]LGE2 adducts. Retinal sections were preincubated in PLA2 digest buffer for 10 min followed by addition of 200 units/ml of PLA2 in PLA2 digest buffer and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C in a humidified chamber. Control sections for the PLA2 digest were processed identically but omitted the PLA2 enzyme. Following incubation, slides were washed in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 for 5 min three times. Slides were then extracted with 70% ethanol in water for 5 min and washed in PBS/Tween for 5 min three times. Sections were blocked with 5% nonimmunized goat serum (Invitrogen) in PBS/Tween (blocking buffer) for 1 h and then incubated with iso[4]LGE2 antiserum or nonimmunized rabbit serum (dilution 1:2500 in blocking buffer) overnight at 4 °C. Slides were washed for 5 min three times in PBS/Tween before incubating with DyLight 649-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch), diluted 1:200 in blocking buffer, for 1 h while protected from light. Slides were washed in PBS/Tween 5 min three times, followed by washes with water for 2 min two times. Excess water was removed by blotting, and slides were mounted with ProLong Gold with DAPI (Invitrogen) and a glass coverslip. For human specimens, retinas were isolated from the dissected eyes and cryosections prepared as described (61). Immunostaining for iso[4]LGE2 was as above but without PLA2 digestion. Sections were examined using a DMI6000B (Leica Microsystems) inverted fluorescent microscope with a ×40 objective lens. Digital images (12-bit) covering all retinal layers were acquired with a Retiga EXi-Fast camera (QImaging, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada) and analyzed in Metamorph Imaging software (Downington, PA). DAPI excitation and collection wavelengths were 340–380 and 450–490 nm, respectively. Exposure time was 100 ms. DyLight 649 excitation and collection wavelengths were 590–650 and 663–733 nm, respectively. Exposure time was 800 ms. Only uniform linear brightness and contrast adjustments were applied.

For full-color autofluorescence images, sections were processed as described above but omitted application of antibodies/serum and were mounted in ProLong Gold without DAPI (Invitrogen) and a glass coverslip. Sections were examined using an Olympus BX60 upright fluorescent microscope. The excitation wavelength was 340–380 nm. Digital color images (24-bit) of fluorescent emission were collected through a 425-nm-long pass filter and a red-green-blue liquid crystal color filter (QImaging) in-line with a Retiga EXi-Aqua camera using Metamorph Imaging software. The signal in each of the color channels was digitally doubled to compensate for transmission losses through the color filter, and exposure times for each of the three colors were adjusted to the following so that the digital image matched the ocular view. The exposure times were 2700 ms for red, 2000 ms for green, and 1600 ms for blue.

Electron Microscopy

Mice from the five-time exposure cohort were sacrificed, and the enucleated eyes were marked to preserve orientation. Eyes were fixed in triple aldehyde fixative with dimethyl sulfoxide (62) for 10 min, dissected to make eyecups, and returned to the fixative for an additional 2 h. Specimens were postfixed, embedded in Epon epoxy resin, sectioned, and stained as described (63). Thin sections (80 nm) of the central retina were examined with a JEOL 1200EX transmission electron microscope. Electron micrographs of all retina layers were acquired at multiple magnifications from ×1500 to ×8000.

Data Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± S.D. B6 vitamers were measured in the serum and retina from three individual animals per group. Comparisons between the two groups were made using the Student's t test assuming a two-tailed distribution, with significance being defined as follows: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. All images are representative of observations in multiple sections from three different animal/donor retinas per group.

RESULTS

Mouse Model

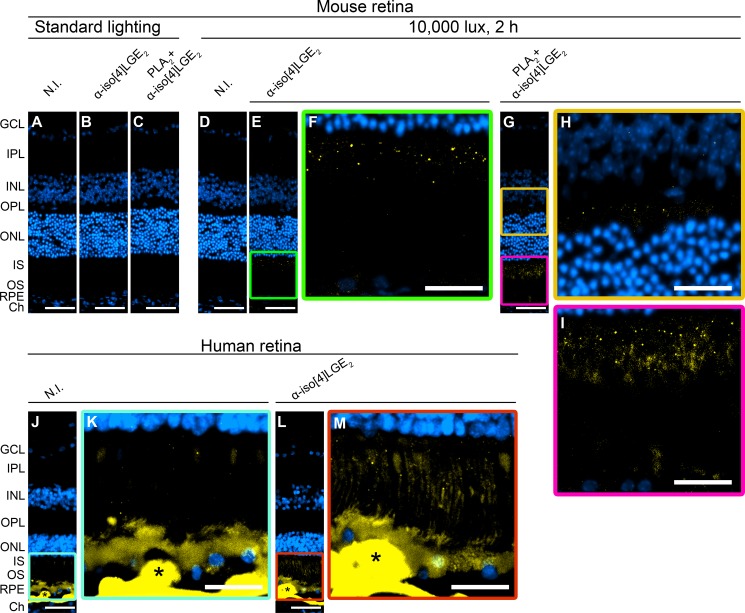

IsoLG adducts were not found in the retina of mice kept under standard, i.e. dim (∼10 lux), lighting conditions as indicated by immunohistochemistry staining of their retinal cross-sections treated with the nonimmunized serum (N.I.) (Fig. 3A) and antiserum against iso[4]LGE2 as a representative isoLG isomer (Fig. 3B). Hence, we had to identify the conditions that induce isoLG production and adduct formation in the retina. Fortuitously, we found that one-time exposure to a 10,000 lux-light source for 2 h leads to a faint staining for iso[4]LGE2 (Fig. 3, E and F). The signal was punctate and localized mainly to the photoreceptor inner segments (IS) with some immunofluorescence also present in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). Because the intensity of the staining was low, tissue sections were then treated with PLA2 before immunostaining. This was done because of a previous finding that in human plasma, isoLG adducts exist as a mixture of free acids and esters of PhosLs (30) with the esterification reducing antibody affinity ∼100-fold (17). Processing of sections from mice after exposure to bright light with PLA2 indeed enhanced staining in the IS and RPE (Fig. 3, G and I) and showed additional staining in the outer plexiform layer (Fig. 3H). There was also an intermittent staining inside the blood vessels in the ganglion cell layer (GCL), not seen in Fig. 3G but observed in Fig. 5, C and D, representing the same light exposure paradigm. The signal increase in Fig. 3, G–I, as a result of the PLA2 treatment demonstrates that in the retina a portion of the isoLG adducts is esterified to PhosLs and that isoLG staining is authentic. Accordingly, PLA2 digestion was used in all subsequent immunohistochemistry experiments and was also incorporated into the sample preparation for quantitative analysis and structural confirmation by MS.

FIGURE 3.

Immunolocalization of iso[4]LGE2 adducts in mouse (A–I) and human (J–M) retina. A, D, J, and K, control stainings in which the nonimmunized (N.I.) serum was used. Control stainings of mouse retina (A and D) showed no background signal. In contrast, control staining of human retina (J and K, from a 72-year-old donor with a history of AMD) had faint background signal in the IS as well as intense background signal in the RPE, BM, and druse (indicated by *), a cholesterol and lipid-containing deposit developed with age in humans. B and C, anti-iso[4]LGE2 immunostaining without or with the PLA2 treatment, respectively, during retina processing of mice kept in dim (∼10 lux) lighting conditions. E–I, anti-iso[4]LGE2 immunostaining without or with the PLA2 treatment, respectively, during retina processing of mice following animal exposure to 10,000 lux for 2 h. L and M, anti-iso[4]LGE2 immunostaining of human retina. In the IS region, the anti-iso[4]LGE2 staining of L and M was more intense than the background staining present in J and K. All images are representative. Immunoreactivity is shown in yellow, and nuclei staining in blue. Scale bars, A–E, G, J, and L, 50 μm; F, H, I, K, and M, 25 μm. The layer labeling is as follows: IPL, inner plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layers; OPL, outer plexiform layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OS, photoreceptor outer segments; BM, Bruch's membrane; Ch, choroid.

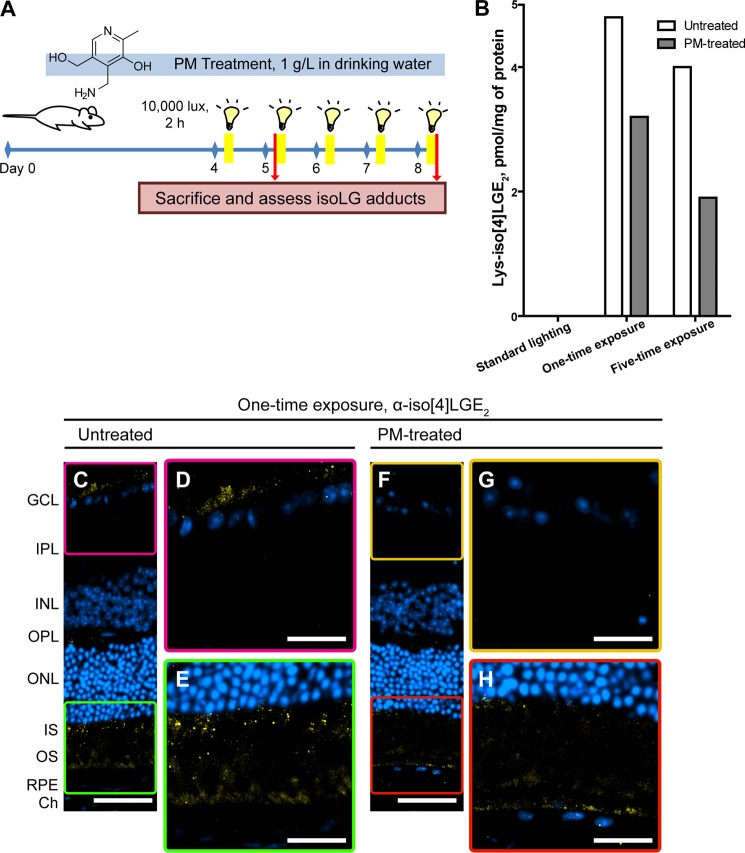

FIGURE 5.

Treatment of mice with PM reduces light-induced isoLG adduct formation in the retina. A, schematic representation of the treatment paradigms. B, levels of isoLG-protein adducts in retina of mice kept in dim lighting conditions or following one-time or five-time exposure to bright light (10,000 lux, 2 h). Analysis was conducted by MRM on pooled samples of four retinas from three different mice. IsoLG adducts were not detected (<0.3 pmol/mg protein) in the retina of mice kept under dim lighting. C–E and F–H, anti-iso[4]LGE2 immunostaining. All images are representative. Immunoreactivity is shown in yellow, and nuclei staining in blue. Stainings with N.I. serum is shown in Fig. 3D. Scale bars, C and F, 50 μm; D, E, G, and H, 25 μm. IPL, inner plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layers; OPL, outer plexiform layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OS, photoreceptor outer segments; Ch, choroid.

To assess the suitability of mouse exposure to bright light as a model for studies of isoLG adducts in human retina, we carried out anti-iso[4]LGE2 staining of retina sections from elderly human donors ages 65–88 years old. The representative staining shows that in contrast to mouse sections, human sections, when treated with nonimmunized serum, have intense background signal in the RPE, Bruch's membrane, and drusen (the latter is not formed in mice) interfering with immunohistochemistry analysis in these layers (Fig. 3, J and K). Nevertheless, when treated with anti-iso[4]LGE2 antibodies, additional immunoreactive signal could be observed and seemed to localize primarily to the IS (Fig. 3, L and M). Similar to mice, the staining was punctate suggesting that adduction occurs in discrete organelles, possibly mitochondria, which densely populate the IS (64, 65), or lysosomes, which have been shown to ingest oxidatively damaged organelles and proteins in ocular tissue (66). Thus, mouse exposure to bright light appears to recapitulate the localization of isoLG adducts in aged human retina, especially when repeated exposures to bright light were used in subsequent studies (Fig. 6).

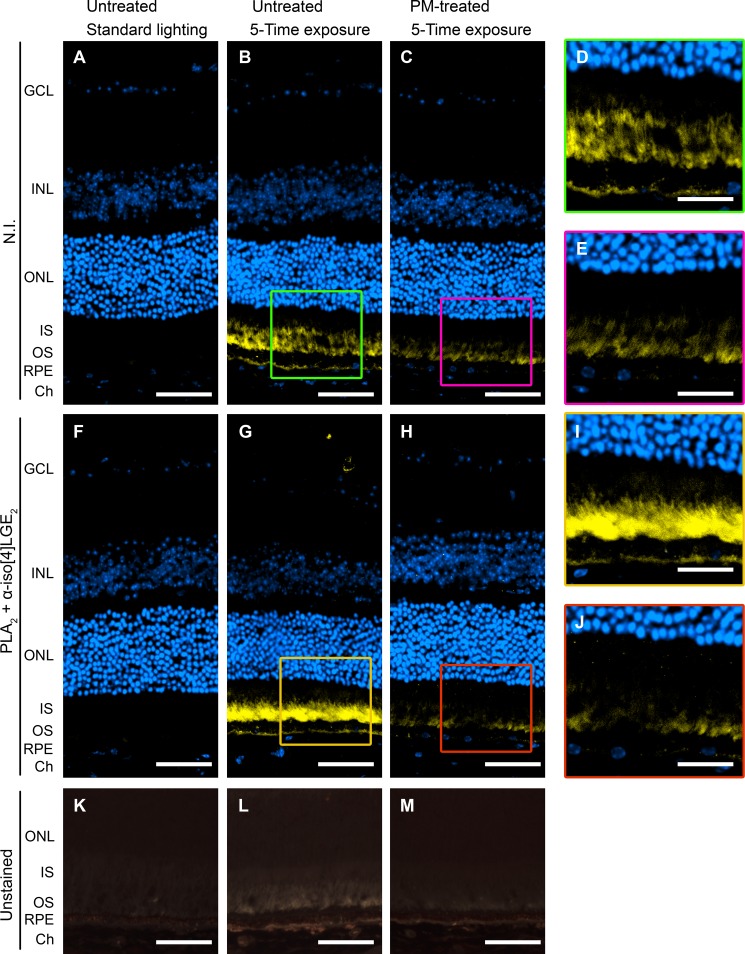

FIGURE 6.

Treatment with PM reduces anti-isoLG signal as well as background fluorescence in the retina of mice exposed five times to bright light (10,000 lux, 2 h). A–E, control stainings in which N.I. serum was used. D and E are enlargements of the boxed areas in B and C, respectively. F–J, anti-iso[4]LGE2 immunostaining. I and J are enlargements of the boxed areas in G and H, respectively. A–J, fluorescent signal (590–650 nm excitation, 663–733 nm emission) is in yellow, and nuclei staining is in blue. K–M, fluorescence (pale yellow and orange) in unstained retinal sections under UV illumination (340–380 nm). All images are representative. Scale bars, A–C, F–H, and K–M, 50 μm; D, E, I, and J, 25 μm. IPL, inner plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layers; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OS, photoreceptor outer segments Ch, choroid.

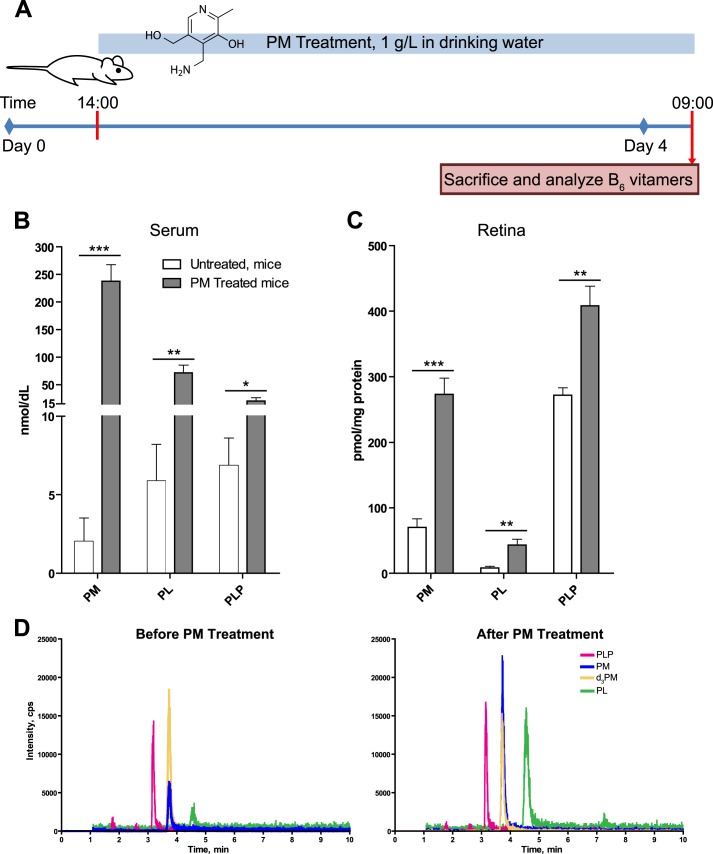

PM Treatment Increases the B6 Vitamers' Levels in Mouse Serum and Retina

PM is water-soluble and has low toxicity with an LD50 (oral) of 5100 mg/kg for mice (material safety data sheet from TCI America). Hence, mice were given PM in drinking water (1 g/liter) as in previous studies by others (51, 67). The duration of treatment was 4 days, much longer than that (6 h) required to establish the steady state plasma PM concentrations based on the reported half-life for plasma PM clearance (1.5 h) (67). Animals were then sacrificed, and their serum and retina were analyzed by MS for different B6 vitamers because these vitamers can be enzymatically interconverted to one another (Fig. 2). Of the six B6 vitamers investigated by MRM, only PM, PL, and PLP were detected in the serum or retina of untreated mice (Fig. 4, B–D). PM was the least abundant vitamer in the serum (2 nmol/dl) with PL and PLP being more abundant and present at similar levels (6 and 7 nmol/dl, respectively). PM treatment increased serum concentrations of all three vitamers, 119-fold of PM, 12-fold of PL, and 3-fold of PLP (Fig. 4B), and did not lead to a detection of additional vitamers. The same three vitamers, PM, PL, and PLP, were detected in the retina of untreated mice; however, their ratio was different as compared with that in the serum. PM was the second most abundant vitamer (70 pmol/mg protein) with PLP being the most abundant (272 pmol/mg protein) and PL being the least abundant retinal vitamer (8 pmol/mg protein). PM treatment increased the vitamers' concentrations in the retina, yet the increase was less pronounced than that in the serum for all three vitamers: 3.9-fold increase for PM, 5-fold increase for PL, and 1.5-fold increase for PLP (Fig. 4C). The data obtained demonstrate that PM crosses the blood-brain barrier and that oral administration of PM in drinking water is an effective route for continuous delivery of this compound to the retina. Different ratios of vitamers B6 in the serum and retina before and after PM treatment also indicate that either these vitamers are selectively uptaken by the retina from the blood or they undergo interconversion once in this organ.

FIGURE 4.

Treatment of mice with PM increases B6 vitamer concentrations in serum and retina. A, mice were given either PM-containing (1g/liter) drinking water (PM-treated) or regular drinking water (untreated) for 4 days prior to sacrifice and subsequent MS analysis. B and C, concentration of B6 vitamers in serum and retina, respectively. D, representative MRM chromatograms of B6 vitamers in mouse retina. Traces show PLP (magenta), PM (blue), and PL (green) in untreated and PM-treated mice. The gold trace represents the internal standard d3-PM. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

PM Treatment Reduces IsoLG Adduction in Mice Exposed to Bright Light

The effect of PM treatment on isoLG adduction in mouse retina was assessed in two treatment paradigms (Fig. 5A). In the first, the one-time light exposure paradigm, mice were given PM in the drinking water (1 g/liter) for 4 days and then exposed to bright light (10,000 lux for 2 h). Animals were allowed to recover for 24 h under dim lighting while still receiving PM-containing water. The animals were then sacrificed, and retinal homogenate was sequentially digested with PLA2 to release isoLG adducts from PhosLs and by peptidases to release free amino acids from proteins, including the adducted lysine residues. The lactam form of Lys-isoLG adducts was then quantified by MRM (58) and compared with the retinal Lys-isoLG levels of the animals also undergoing exposure to bright light but provided with the regular drinking water (Fig. 5B). In the second, the five-time exposure paradigm, mice were pretreated with PM in the drinking water for 4 days, exposed daily over the next 5 days to bright light for 2 h, and sacrificed immediately after the 5th exposure. The drinking water during the days of bright light exposure also contained PM. For both treatment paradigms, the control group was mice kept under dim lighting conditions and provided with regular drinking water. This group had undetectable levels of Lys-isoLG lactam in the retina (Fig. 5B). In contrast, in the one-time exposure cohort, retina from mice exposed to bright light but untreated with PM contained 4.8 pmol of Lys-isoLG lactam/mg of protein. PM treatment, however, reduced the levels of Lys-isoLG lactam to 3.2 pmol, a 1.5-fold reduction. In the five-time exposure cohort, retina of PM untreated mice had a similar content of Lys-isoLG lactam (4.0 pmol), yet the decrease in isoLG adduction upon the treatment with PM was higher (2-fold). Thus, in both light exposure paradigms, the levels of isoLG-Lys adducts were lower in the PM-treated animals than in untreated mice.

Localization of the PM Protective Effect to Retinal Layers

Immunostaining was used to determine which retinal layer(s) had diminished isoLG adduction upon the treatment with PM. In the one-time light exposure cohort, PM treatment reduced, but not completely eliminated, the intensity of anti-iso[4]LGE2 fluorescence in the GCL and IS, the layers where bright light exposure triggers isoLG adduction (Fig. 5, C–H). Similarly, the immunofluorescence was reduced in the GCL and perhaps IS in the PM-treated five-time exposure cohort (Fig. 6, G–J), with the pattern of staining in the IS being diffuse for PM-untreated group (Fig. 6I) and punctate for the PM-treated group (Fig. 6J). Because of the background signal (Fig. 6, B–E), the interpretations for the IS are more equivocal, yet they are supported by subsequent EM examination, which provided an explanation for the diffuse versus punctate staining. In the five-time exposure cohort, strong background signal was also present in the photoreceptor outer segments and along the basal side of the RPE. Surprisingly, PM treatment seemed to reduce the intensity of the background signal in these layers. This prompted us to investigate if this background signal represented fluorescence from endogenous material, i.e. autofluorescence. Accordingly, unstained sections were viewed under UV illumination (Fig. 6, K–M). In animals kept under dim lighting, sparse orange fluorescence was distributed throughout the RPE (Fig. 6K). However, in animals exposed to bright light (Fig. 6, L and M), the fluorescence was of two colors, pale yellow and orange, and seen in the photoreceptor outer segments and flanking region of the IS, and to a lesser extent along the basal aspect of the RPE. The intensity of fluorescence was greater in mice from the untreated group compared with the PM-treated group (Fig. 6, L and M), a trend similar to that seen with the anti-iso[4]LGE2 staining. In addition, in all groups, there was fluorescence of red-orange color in the choroid, likely originating from the disk-shaped erythrocytes (68). Thus, not only did PM treatment reduce the anti-isoLG signal but also the fluorescent signal potentially from autofluorescence, as it has color similar to the color of autofluorescent retinoid conjugates accumulating in animals upon exposure to bright light (69), the toxic by-products of the visual cycle (70). Importantly, this decrease in the fluorescent/autofluorescent signal was observed in the photoreceptor OS, responsible for initiating the visual transduction cascade essential for normal vision, as well as the underlying RPE responsible for the nutrient supply and waste removal from the neural retina.

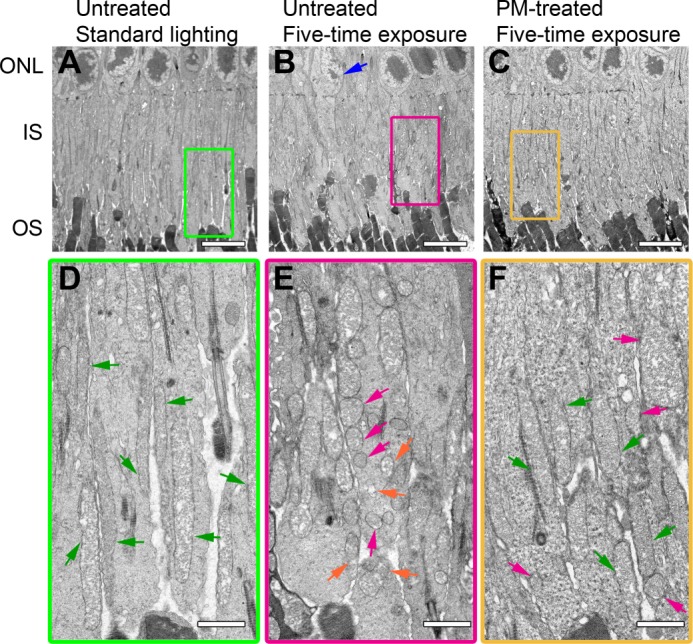

PM Treatment Diminishes Light-induced Alteration of Mitochondrial Morphology in the IS

Exposure of mice to bright light was shown to cause alterations in retinal structure (71–75). Hence, we used electron microscopy to examine the retina in different cohorts of mice in the five-time treatment paradigm. Electron micrographs of all retinal layers showed that the mitochondria in the IS were the most affected organelles (Fig. 7). In mice that were not exposed to bright light, mitochondria of the IS had elongated and cylindrical morphology (Fig. 7, A and D), characteristic of a healthy retina (73, 75). In contrast, in mice exposed to bright light and having no treatment with PM (Fig. 7, B and E), only a few of the IS mitochondria retained a normal structure. In this cohort, many of the IS mitochondria were short and round either as a result of mitochondrial fragmentation or due to mitochondrial disruption and total damage (magenta and orange arrows in Fig. 7E, respectively). Mitochondrial disruption and fragmentation explain the diffuse pattern of the anti-isoLG staining in Fig. 6I as the content of mitochondria is likely released, at least in part, when they open. Karyolytic nuclei concomitant with IS and OS degeneration, indicative of photoreceptor apoptosis (70), were also observed. The PM treatment increased a proportion of mitochondria with a normal elongated morphology, although mitochondria with altered morphology were still observed (Fig. 7, C and F). This increase in a proportion of normally shaped mitochondria likely restored a punctate pattern of anti-isoLG staining in the IS in Fig. 6J. Thus, PM treatment seems to protect in part light-induced mitochondrial damage, and the protective effect observed in the layer, IS, also associated with the light-induced isoLG adduction.

FIGURE 7.

Treatment with PM diminishes light-induced disruption of mitochondrial morphology in the IS. A–C, lower magnification (×1500) EM micrographs of the IS. D–F, higher magnification (×4000) views of the boxed areas in A–C. B, blue arrow indicates a photoreceptor with karyolytic nucleus. D, green arrows show mitochondria of normal elongated morphology. E, magenta arrows indicate fragmented mitochondria with intact outer membranes, and orange arrows show disrupted or totally damaged mitochondria. All images are representative. Scale bars, A–C, 5 μm; D–F, 1 μm. ONL, outer nuclear layer; OS, photoreceptor outer segments.

DISCUSSION

In this work, we conducted proof-of-concept experiments on mice and used the retina as a target organ to demonstrate that pharmacological targeting of the downstream events in the oxidative injury cascade (Fig. 1), e.g. effects of lipid peroxidation products, reduces deleterious consequences associated with oxidative stress. The recent age-related eye disease study showed that intake of high levels of antioxidants (vitamins A and E and β-carotene) plus zinc and cupric oxides reduced by 25% the risk of progression to advanced AMD of only the patients having intermediate stage AMD but not those at the early stages of the disease. Also, no benefits were observed when zinc oxide was omitted (39, 40). In view of the limited efficacy of targeting the initial oxidative insult, we postulated that focusing on the downstream effects induced by oxidative stress could be a complementary or alternative strategy to inhibiting the formation of reactive oxygen intermediates by general antioxidants. To test this strategy, we first had to generate an animal model because mouse retina does not normally show immunostaining for isoLG adducts. We decided to evaluate exposure to bright light because this insult has been previously used in rodents to cause retinal damage and accelerate photoreceptor degeneration, especially in albino animals or mice rendered light-sensitive by genetic manipulation (76–78). Moreover, illumination with 1000 to 5000 lux for 1–24 h has also been used to induce fatty acid (79) and cholesterol oxidation (80) as well as the formation of 4-hydroxynonenal adducts (81, 82). We used 10,000 lux illumination for 2 h, either one time or five times, and in both exposure paradigms observed retinal isoLG adduction as shown by MS analysis and consistent with immunohistochemistry stainings. When combined with the results of the previous light-exposure studies (81, 82), these data suggest that isoLGs are likely formed in parallel with other lipid oxidation products as a part of the oxidative stress induced in mouse retina by the insult with bright light. Accordingly, our model appears to be suitable for testing the efficacy of pharmacological interventions of the events secondary to lipid peroxidation, including post-translational protein modifications with isoLGs. Importantly, the pattern of staining for isoLG adducts in our mouse model is similar to the pattern observed in aged human retina (Fig. 3, K and L).

Previously, supplementation of rats with PM, 1 g/liter in drinking water, was shown to ameliorate symptoms of diabetic retinopathy, like capillary dropout, by preventing the formation of advanced glycation end products (51). However, diabetic retinopathy is in large part a pathology of retinal vasculature (83); hence, this effect could have been due to elevated PM concentration in the serum only. Therefore, in this study, it was necessary to demonstrate that oral administration increases PM concentration in the retina as well. This was a challenge because the retina is a tiny organ, ∼2.5 mg of wet tissue containing ∼250 μg of total protein, and we wanted to measure all six B6 vitamers. To achieve these quantitative goals, we selected MRM, a highly sensitive and accurate MS method. We developed a protocol for retinal processing and report here the first determination of the base-line levels of PM as well as other B6 vitamers in mouse retina. We show that the proportions between these vitamers are different in the retina as compared with those in the serum suggesting that the retina maintains its pool of B6 vitamers independently from the systemic circulation. This could be due to either the presence of the blood-retina barrier and selective retinal uptake of B6 vitamers or metabolism of the uptaken vitamers in the retina. We also confirmed that our treatment paradigm increased PM concentration in the retina almost 4-fold (Fig. 4C).

Providing our mouse model with PM, an avid isoLG scavenger in vitro and tissue culture (26, 47, 48), reduced the isoLG modification of retinal proteins by up to 2-fold (Fig. 5B), thus confirming that PM is also an effective scavenger of γ-ketoaldehydes in vivo. This reduction in isoLG adduction was mainly localized to the photoreceptor IS (Fig. 5, F and H), a layer particularly rich in mitochondria, which produce, under normal conditions, the majority of reactive oxygen species (84). Altered mitochondrial morphology in mice following light exposure in this work is in line with our previous investigation, in which we used MRM and demonstrated that the retina of an AMD-affected donor contains isoLG adducts of a mitochondrial enzyme cytochrome P450 27A1 (24). Thus, this study on mice supports and further strengthens the isoLG-mitochondria link discovered initially by mass spectrometry analysis of human retina. Changes in mitochondrial morphology is an established effect of light exposure (73–75); however, this is the first time isoLG adduction has been linked to morphological changes in mitochondria in vivo. We show that when isoLG adduct formation is diminished through PM treatment, mitochondria are more protected against exposure to bright light. This finding is consistent with prior studies showing that treatment of isolated cardiac and hepatic mitochondria with isoLGs leads to mitochondrial swelling and impaired mitochondrial respiration (28). Mitochondrial morphology and function are also reported to be altered in the brains of people affected by Alzheimer (85) and Parkinson (86) diseases and possibly in the retina of those afflicted with AMD (87), pathological conditions coincident with increased lipid peroxidation (4–12). Combined with the results of this work, the available data suggest that isoLG adduction to mitochondrial proteins may play a role in the mitochondrial dysfunction of these diseases and could be not only a biomarker of oxidative stress (88) but also a causative disease factor. The latter is especially pertinent to AMD; increased isoLG adduction does occur in this disease as indicated by the increased serum levels of isoLG adducts to PhoLs (30), and we demonstrated previously that the isoLG adduction occurs in the retina and involves proteins (24). Because isoLGs are promiscuous in protein modification, they could also affect organelles other than mitochondria. Yet, these organelles remain to be identified.

This study also provides important insight into the cellular environment of the arachidonate that is oxidized to form isoLGs. Nonenzymatic oxidation via free radicals can occur either with free arachidonic acid or with arachidonyl esters in PhosLs, forming PhosL-bound isoLGs in cellular membranes (17). Consequently, the resultant isoLG-protein adducts can exist either as a free carboxylic acid or remain esterified to a PhosL. Increased signal after treatment of the sections with PLA2 in our immunostaining experiments indicates that both the free and esterified forms of IsoLG adducts are present in the retina. IsoLGs are extremely reactive and remain unadducted only for a short time, on the order of seconds in vitro (18, 20). This suggests that membrane-bound proteins would be among the first targets for adduction by the membrane-tethered PhosL-bound isoLGs. The membrane origin of isoLGs is consistent with our previous finding of modification of cytochrome P450 27A1, which is peripherally associated with the inner mitochondrial membrane.

A potential source of free radicals to mediate conversion of arachidonate to isoLGs could be the Fenton reaction, in which Fe2+ catalyzes the conversion of hydrogen peroxide to hydroxyl and peroxide radicals. Furthermore, light exposure has been shown to trigger the release of Fe2+ from ferritin (89, 90), an iron storage protein relatively abundant in the IS, outer plexiform layer, and GCL (91, 92). Additionally, light exposure of isolated photoreceptors and low density lipoprotein particles was shown to promote free-radical lipid oxidation in the presence of ferritin (93) and cholesterol oxidation (80), respectively. Supporting this hypothesis is the finding that treating mice with the iron-chelating agent deferiprone was protective against light-induced photodamage (94). PM itself has been shown to act as an iron chelator (95) and may therefore reduce isoLG adducts by lowering Fenton-derived free radicals. Another cause of isoLG formation in the retina could be free radicals produced by retinoid-derived pigments such as A2E (96, 97). Administration of certain drugs containing a primary amino group prevents accumulation of retinoid conjugates in the retina of mice following exposure to bright light (56). Hence, PM, which also contains a primary amino group, might in addition prevent accumulation of retinoid conjugates, accounting for the observed reduction in autofluorescence. It is thus possible that PM may simultaneously scavenge γ-ketoaldehydes, remove catalysts of free-radical formation, and lessen accumulation of retinoid conjugates.

PM was previously marketed as a dietary supplement. The safety of this compound was confirmed during the phase I and II clinical trials evaluating the effect of PM on the serum creatinine levels in patients with type 2 diabetic nephropathy (52, 53). Although the trial failed to detect an effect of PM on the progression of serum creatinine at 1 year, the use of PM, twice a day at 150 or 300 mg, was not associated with an increase in the adverse or severe adverse events in the treatments groups. Hence, we propose that that PM supplementation be considered for inclusion in future revisions of the age-related eye disease study vitamin formulations, the current standard of care for nonvascular AMD (39, 98).

In summary, we developed a mouse model for the study of isoLG adduction in the retina. We found that isoLGs are formed in the retina from free arachidonate and arachidonate incorporated in membrane PhosLs. We established that light-induced isoLG protein modification takes place primarily in the photoreceptor IS. We demonstrate that PM is an effective scavenger of isoLGs in mouse retina and that PM diminishes post-translational modification of retinal proteins by these lipid peroxidation products. Moreover, PM was partially protective against changes in mitochondrial morphology caused by repeated exposures to intense light. The data obtained enhance our knowledge of lipid peroxidation in the eye and introduce a new concept in the vision field that has medical relevance and could immediately be tested on humans as PM has good drug-like properties and an excellent safety profile.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Natalia Mast and Yong Li in the Pikuleva laboratory for their assistance; Dr. Christine Curcio and Susan Vogt, MS, for providing human specimens and training and expertise in human retina sectioning and immunohistochemistry; Dr. Hisashi Fujioka of the Case Western EM core facility; Dr. Scott Howell and Catherine Doller of the Case Western Visual Sciences Research Center; Dr. Shenghui Zhang of the Case Western Mouse Metabolomic Phenotyping Center; and Dr. Yunfeng Xu and Yuanyuan Qian, MS, for synthesis of the d6-Std peptide standard.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants EY018383 (to I. A. P.), GM21249 (to R. G. S.), and R33DK070291 (to H. B.), and Visual Sciences Research Center Core Grant P30 EY11373. This work was also supported by the Jules and Doris Stein Research Professorship from Research to Prevent Blindness (to I. A. P.).

- AMD

- age-related macular degeneration

- d3-PM

- [2H3]methylpyridoxamine

- d6-Std

- 2H6-labeled internal standard

- GCL

- ganglion cell layer

- IS

- inner segment

- isoLG

- isolevuglandins

- iso[4]LGE2

- iso[4]levuglandin E2

- MRM

- multiple reaction monitoring

- N.I.

- nonimmunized serum

- PhosL

- phospholipid

- PL

- pyridoxal

- PLP

- pyridoxal phosphate

- PM

- pyridoxamine

- RPE

- retinal pigment epithelium

- PLA

- phospholipase A2.

REFERENCES

- 1. Haberland M. E., Fong D., Cheng L. (1988) Malondialdehyde-altered protein occurs in atheroma of Watanabe heritable hyperlipidemic rabbits. Science 241, 215–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hennig B., Chow C. K. (1988) Lipid peroxidation and endothelial cell injury: implications in atherosclerosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 4, 99–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Salomon R. G., Kaur K., Batyreva E. (2000) Isolevuglandin-protein adducts in oxidized low density lipoprotein and human plasma: a strong connection with cardiovascular disease. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 10, 53–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sayre L. M., Zelasko D. A., Harris P. L., Perry G., Salomon R. G., Smith M. A. (1997) 4-Hydroxynonenal-derived advanced lipid peroxidation end products are increased in Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurochem. 68, 2092–2097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Markesbery W. R., Lovell M. A. (1998) Four-hydroxynonenal, a product of lipid peroxidation, is increased in the brain in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging 19, 33–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zagol-Ikapitte I., Masterson T. S., Amarnath V., Montine T. J., Andreasson K. I., Boutaud O., Oates J. A. (2005) Prostaglandin H(2)-derived adducts of proteins correlate with Alzheimer's disease severity. J. Neurochem. 94, 1140–1145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dexter D. T., Carter C. J., Wells F. R., Javoy-Agid F., Agid Y., Lees A., Jenner P., Marsden C. D. (1989) Basal lipid peroxidation in substantia nigra is increased in Parkinson's disease. J. Neurochem. 52, 381–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yoritaka A., Hattori N., Uchida K., Tanaka M., Stadtman E. R., Mizuno Y. (1996) Immunohistochemical detection of 4-hydroxynonenal protein adducts in Parkinson disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 2696–2701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Beatty S., Koh H.-H., Phil M., Henson D., Boulton M. (2000) The role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Surv. Ophthalmol. 45, 115–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ebrahem Q., Renganathan K., Sears J., Vasanji A., Gu X., Lu L., Salomon R. G., Crabb J. W., Anand-Apte B. (2006) Carboxyethylpyrrole oxidative protein modifications stimulate neovascularization: implications for age-related macular degeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A, 103, 13480–13484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hollyfield J. G., Bonilha V. L., Rayborn M. E., Yang X., Shadrach K. G., Lu L., Ufret R. L., Salomon R. G., Perez V. L. (2008) Oxidative damage-induced inflammation initiates age-related macular degeneration. Nat. Med. 14, 194–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gu X., Meer S. G., Miyagi M., Rayborn M. E., Hollyfield J. G., Crabb J. W., Salomon R. G. (2003) Carboxyethylpyrrole protein adducts and autoantibodies, biomarkers for age-related macular degeneration. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 42027–42035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Xu L., Davis T. A., Porter N. A. (2009) Rate constants for peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids and sterols in solution and in liposomes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 13037–13044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Esterbauer H., Schaur R. J., Zollner H. (1991) Chemistry and biochemistry of 4-hydroxynonenal, malonaldehyde and related aldehydes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 11, 81–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kaur K., Salomon R. G., O'Neil J., Hoff H. F. (1997) (Carboxyalkyl)pyrroles in human plasma and oxidized low-density lipoproteins. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 10, 1387–1396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Salomon R. G., Miller D. B. (1985) Levuglandins: isolation, characterization, and total synthesis of new secoprostanoid products from prostaglandin endoperoxides. Adv. Prostaglandin Thromboxane Leukot. Res. 15, 323–326 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Salomon R. G., Subbanagounder G., Singh U., O'Neil J., Hoff H. F. (1997) Oxidation of low-density lipoproteins produces levuglandin-protein adducts. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 10, 750–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. DiFranco E., Subbanagounder G., Kim S., Murthi K., Taneda S., Monnier V. M., Salomon R. G. (1995) Formation and stability of pyrrole adducts in the reaction of levuglandin E2 with proteins. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 8, 61–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Salomon R. G., Sha W., Brame C., Kaur K., Subbanagounder G., O'Neil J., Hoff H. F., Roberts L. J., 2nd (1999) Protein adducts of iso[4]levuglandin E2, a product of the isoprostane pathway, in oxidized low density lipoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 20271–20280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brame C. J., Salomon R. G., Morrow J. D., Roberts L. J., 2nd (1999) Identification of extremely reactive γ-ketoaldehydes (isolevuglandins) as products of the isoprostane pathway and characterization of their lysyl protein adducts. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 13139–13146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sha W., Salomon R. G. (2000) Total synthesis of 17-isolevuglandin E4 and the structure of C22-PGF4α. J. Org. Chem. 65, 5315–5326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Houglum K., Filip M., Witztum J. L., Chojkier M. (1990) Malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxynonenal protein adducts in plasma and liver of rats with iron overload. J. Clin. Invest. 86, 1991–1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Siems W. G., Hapner S. J., van Kuijk F. J. (1996) 4-Hydroxynonenal inhibits NA+-K+-ATPase. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 20, 215–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Charvet C., Liao W. L., Heo G. Y., Laird J., Salomon R. G., Turko I. V., Pikuleva I. A. (2011) Isolevuglandins and mitochondrial enzymes in the retina: mass spectrometry detection of post-translational modification of sterol-metabolizing CYP27A1. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 20413–20422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Govindarajan B., Laird J., Salomon R. G., Bhattacharya S. K. (2008) Isolevuglandin-modified proteins, including elevated levels of inactive calpain-1, accumulate in glaucomatous trabecular meshwork. Biochemistry 47, 817–825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Davies S. S., Brantley E. J., Voziyan P. A., Amarnath V., Zagol-Ikapitte I., Boutaud O., Hudson B. G., Oates J. A., Roberts L. J., 2nd (2006) Pyridoxamine analogues scavenge lipid-derived γ-ketoaldehydes and protect against H2O2-mediated cytotoxicity. Biochemistry 45, 15756–15767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fukuda K., Davies S. S., Nakajima T., Ong B.-H., Kupershmidt S., Fessel J., Amarnath V., Anderson M. E., Boyden P. A., Viswanathan P. C., Roberts L. J., 2nd, Balser J. R. (2005) Oxidative mediated lipid peroxidation recapitulates proarrhythmic effects on cardiac sodium channels. Circ. Res. 97, 1262–1269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stavrovskaya I. G., Baranov S. V., Guo X., Davies S. S., Roberts L. J., 2nd, Kristal B. S. (2010) Reactive γ-ketoaldehydes formed via the isoprostane pathway disrupt mitochondrial respiration and calcium homeostasis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 49, 567–579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bacot S., Bernoud-Hubac N., Baddas N., Chantegrel B., Deshayes C., Doutheau A., Lagarde M., Guichardant M. (2003) Covalent binding of hydroxy-alkenals 4-HDDE, 4-HHE, and 4-HNE to ethanolamine phospholipid subclasses. J. Lipid Res. 44, 917–926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li W., Laird J. M., Lu L., Roychowdhury S., Nagy L. E., Zhou R., Crabb J. W., Salomon R. G. (2009) Isolevuglandins covalently modify phosphatidylethanolamines in vivo: detection and quantitative analysis of hydroxylactam adducts. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 47, 1539–1552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sullivan C. B., Matafonova E., Roberts L. J., 2nd, Amarnath V., Davies S. S. (2010) Isoketals form cytotoxic phosphatidylethanolamine adducts in cells. J. Lipid Res. 51, 999–1009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Basu A. K., Marnett L. J., Romano L. J. (1984) Dissociation of malondialdehyde mutagenicity in Salmonella typhimurium from its ability to induce interstrand DNA cross-links. Mutat. Res. 129, 39–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Eder E., Hoffman C., Bastian H., Deininger C., Scheckenbach S. (1990) Molecular mechanisms of DNA damage initiated by α,β-unsaturated carbonyl-compounds as criteria for genotoxicity and mutagenicity. Environ. Health Perspect. 88, 99–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Esterbauer H. (1993) Cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of lipid-oxidation products. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 57, 779S–785S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dalle-Donne I., Rossi R., Colombo R., Giustarini D., Milzani A. (2006) Biomarkers of oxidative damage in human disease. Clin. Chem. 52, 601–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kris-Etherton P. M., Lichtenstein A. H., Howard B. V., Steinberg D., Witztum J. L., and Nutrition Committee of the American Heart Association Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism (2004) Antioxidant vitamin supplements and cardiovascular disease. Circulation 110, 637–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jump D. B., Depner C. M., Tripathy S. (2012) ω-3 fatty acid supplementation and cardiovascular disease. J. Lipid Res. 53, 2525–2545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Morris M. C., Evans D. A., Bienias J. L., Tangney C. C., Bennett D. A., Aggarwal N., Wilson R. S., Scherr P. A. (2002) Dietary intake of antioxidant nutrients and the risk of incident Alzheimer disease in a biracial community study. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 287, 3230–3237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chew E. Y., Lindblad A. S., Clemons T. (2009) Summary results and recommendations from the age-related eye disease study. Arch. Ophthalmol. 127, 1678–1679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group (2001) A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, β-carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss-AREDS report no. 8. Arch. Ophthalmol. 119, 1417–1436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yu D. Y., Cringle S. J. (2001) Oxygen distribution and consumption within the retina in vascularised and avascular retinas and in animal models of retinal disease. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 20, 175–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gülcan H. G., Alvarez R. A., Maude M. B., Anderson R. E. (1993) Lipids of human retina, retinal pigment epithelium, and Bruch's membrane/choroid: comparison of macular and peripheral regions. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 34, 3187–3193 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pascolini D., Mariotti S. P., Pokharel G. P., Pararajasegaram R., Etya'ale D., Négrel A. D., Resnikoff S. (2004) 2002 global update of available data on visual impairment: a compilation of population-based prevalence studies. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 11, 67–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Crabb J. W., Miyagi M., Gu X., Shadrach K., West K. A., Sakaguchi H., Kamei M., Hasan A., Yan L., Rayborn M. E., Salomon R. G., Hollyfield J. G. (2002) Drusen proteome analysis: an approach to the etiology of age-related macular degeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 14682–14687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Davies S. S., Amarnath V., Roberts L. J., 2nd (2004) Isoketals: highly reactive γ-ketoaldehydes formed from the H2-isoprostane pathway. Chem. Phys. Lipids 128, 85–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Caldés C., Vilanova B., Adrover M., Muñoz F., Donoso J. (2011) Phenol group in pyridoxamine acts as a stabilizing element for its carbinolamines and Schiff bases. Chem. Biodivers. 8, 1318–1332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Onorato J. M., Jenkins A. J., Thorpe S. R., Baynes J. W. (2000) Pyridoxamine, an inhibitor of advanced glycation reactions, also inhibits advanced lipoxidation reactions. Mechanism of action of pyridoxamine. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 21177–21184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Govindarajan B., Junk A., Algeciras M., Salomon R. G., Bhattacharya S. K. (2009) Increased isolevuglandin-modified proteins in glaucomatous astrocytes. Mol. Vis. 15, 1079–1091 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Davies S. S., Bodine C., Matafonova E., Pantazides B. G., Bernoud-Hubac N., Harrison F. E., Olson S. J., Montine T. J., Amarnath V., Roberts L. J., 2nd (2011) Treatment with a γ-ketoaldehyde scavenger prevents working memory deficits in hApoE4 mice. J. Alzheimers Dis. 27, 49–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Metz T. O., Alderson N. L., Thorpe S. R., Baynes J. W. (2003) Pyridoxamine, an inhibitor of advanced glycation and lipoxidation reactions: a novel therapy for treatment of diabetic complications. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 419, 41–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Stitt A., Gardiner T. A., Alderson N. L., Canning P., Frizzell N., Duffy N., Boyle C., Januszewski A. S., Chachich M., Baynes J. W., Thorpe S. R. (2002) The AGE inhibitor pyridoxamine inhibits development of retinopathy in experimental diabetes. Diabetes 51, 2826–2832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Williams M. E., Bolton W. K., Khalifah R. G., Degenhardt T. P., Schotzinger R. J., McGill J. B. (2007) Effects of pyridoxamine in combined phase 2 studies of patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes and overt nephropathy. Am. J. Nephrol. 27, 605–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lewis E. J., Greene T., Spitalewiz S., Blumenthal S., Berl T., Hunsicker L. G., Pohl M. A., Rohde R. D., Raz I., Yerushalmy Y., Yagil Y., Herskovits T., Atkins R. C., Reutens A. T., Packham D. K., Lewis J. B., and Collaborative Study Group (2012) Pyridorin in type 2 diabetic nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 23, 131–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Subbanagounder G., Salomon R. G., Murthi K. K., Brame C., Roberts L. J. (1997) Total synthesis of iso[4]-levuglandin E2. J. Org. Chem. 62, 7658–7666 [Google Scholar]

- 55. Bachmanov A. A., Reed D. R., Beauchamp G. K., Tordoff M. G. (2002) Food intake, water intake, and drinking spout side preference of 28 mouse strains. Behav. Genet. 32, 435–443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Maeda A., Golczak M., Chen Y., Okano K., Kohno H., Shiose S., Ishikawa K., Harte W., Palczewska G., Maeda T., Palczewski K. (2012) Primary amines protect against retinal degeneration in mouse models of retinopathies. Nat. Chem. Biol. 8, 170–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. van der Ham M., Albersen M., de Koning T. J., Visser G., Middendorp A., Bosma M., Verhoeven-Duif N. M., de Sain-van der Velden M. G. (2012) Quantification of vitamin B6 vitamers in human cerebrospinal fluid by ultra performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chim. Acta 712, 108–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Charvet C. D., Laird J., Xu Y., Salomon R. G., Pikuleva I. A. (2013) Post-translational modification by an isolevuglandin diminishes activity of the mitochondrial cytochrome P450 27A1. J. Lipid Res. 54, 1421–1429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Liao W. L., Turko I. V. (2008) Strategy combining separation of isotope-labeled unfolded proteins and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry analysis enables quantification of a wide range of serum proteins. Anal. Biochem. 377, 55–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Omarova S., Charvet C. D., Reem R. E., Mast N., Zheng W., Huang S., Peachey N. S., Pikuleva I. A. (2012) Abnormal vascularization in mouse retina with dysregulated retinal cholesterol homeostasis. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 3012–3023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Malek G., Li C. M., Guidry C., Medeiros N. E., Curcio C. A. (2003) Apolipoprotein B in cholesterol-containing drusen and basal deposits of human eyes with age-related maculopathy. Am. J. Pathol. 162, 413–425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tandler B., Hoppel C. L. (1972) Possible division of cardiac mitochondria. Anat. Rec. 173, 309–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Imanishi Y., Sun W., Maeda T., Maeda A., Palczewski K. (2008) Retinyl ester homeostasis in the adipose differentiation-related protein-deficient retina. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 25091–25102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Hoang Q. V., Linsenmeier R. A., Chung C. K., Curcio C. A. (2002) Photoreceptor inner segments in monkey and human retina: mitochondrial density, optics, and regional variation. Vis. Neurosci. 19, 395–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Stone J., van Driel D., Valter K., Rees S., Provis J. (2008) The locations of mitochondria in mammalian photoreceptors: relation to retinal vasculature. Brain Res. 1189, 58–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Liton P. B., Lin Y., Luna C., Li G., Gonzalez P., Epstein D. L. (2008) Cultured porcine trabecular meshwork cells display altered lysosomal function when subjected to chronic oxidative stress. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 49, 3961–3969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Degenhardt T. P., Alderson N. L., Arrington D. D., Beattie R. J., Basgen J. M., Steffes M. W., Thorpe S. R., Baynes J. W. (2002) Pyridoxamine inhibits early renal disease and dyslipidemia in the streptozotocin-diabetic rat. Kidney Int. 61, 939–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Rimington C., Cripps D. J. (1965) Biochemical and fluorescence-microscopy screening-tests for erythropoietic protoporphyria. Lancet 1, 624–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Ben-Shabat S., Parish C. A., Vollmer H. R., Itagaki Y., Fishkin N., Nakanishi K., Sparrow J. R. (2002) Biosynthetic studies of A2E, a major fluorophore of retinal pigment epithelial lipofuscin. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 7183–7190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wenzel A., Grimm C., Samardzija M., Remé C. E. (2005) Molecular mechanisms of light-induced photoreceptor apoptosis and neuroprotection for retinal degeneration. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 24, 275–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Wenzel A., Reme C. E., Williams T. P., Hafezi F., Grimm C. (2001) The RPE65 Leu450Met variation increases retinal resistance against light-induced degeneration by slowing rhodopsin regeneration. J. Neurosci. 21, 53–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. LaVail M. M., Gorrin G. M., Repaci M. A. (1987) Strain differences in sensitivity to light-induced photoreceptor degeneration in albino mice. Curr. Eye Res. 6, 825–834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Roca A., Shin K. J., Liu X., Simon M. I., Chen J. (2004) Comparative analysis of transcriptional profiles between two apoptotic pathways of light-induced retinal degeneration. Neuroscience 129, 779–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Donovan M., Carmody R. J., Cotter T. G. (2001) Light-induced photoreceptor apoptosis in vivo requires neuronal nitric-oxide synthase and guanylate cyclase activity and is caspase-3-independent. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 23000–23008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Smith R. S. (2001) in Systematic Evaluation of the Mouse Eye: Anatomy, Pathology, and Biomethods (Smith R. S., Editor-in-Chief, and John S. W. M., Nishina P. M., Sundberg J. P., eds) pp. 25–44, CRC Press, Inc., Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- 76. Noell W. K., Walker V. S., Kang B. S., Berman S. (1966) Retinal damage by light in rats. Invest. Ophthalmol. 5, 450–473 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Chen L., Wu W., Dentchev T., Zeng Y., Wang J., Tsui I., Tobias J. W., Bennett J., Baldwin D., Dunaief J. L. (2004) Light damage induced changes in mouse retinal gene expression. Exp. Eye Res. 79, 239–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Maeda A., Maeda T., Golczak M., Palczewski K. (2008) Retinopathy in mice induced by disrupted all-trans-retinal clearance. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 26684–26693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Fliesler S. J., Anderson R. E. (1983) Chemistry and metabolism of lipids in the vertebrate retina. Prog. Lipid Res. 22, 79–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Rodriguez I. R., Fliesler S. J. (2009) Photodamage generates 7-keto- and 7-hydroxycholesterol in the rat retina via a free radical-mediated mechanism. Photochem. Photobiol. 85, 1116–1125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Tanito M., Elliott M. H., Kotake Y., Anderson R. E. (2005) Protein modifications by 4-hydroxynonenal and 4-hydroxyhexenal in light-exposed rat retina. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 46, 3859–3868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Marchette L. D., Thompson D. A., Kravtsova M., Ngansop T. N., Mandal M. N., Kasus-Jacobi A. (2010) Retinol dehydrogenase 12 detoxifies 4-hydroxynonenal in photoreceptor cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 48, 16–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Levin L. A., Kaufman P. L. (2011) in Adler's Physiology of the Eye: Clinical Application (Levin L. A., Nilsson S. F. E., Ver Hoeve J., Wu S., eds) 11th Ed., pp. 243–272, Saunders/Elsevier, Edinburgh, UK [Google Scholar]

- 84. Lambert A. J., Brand M. D. (2009) Reactive oxygen species production by mitochondria. Methods Mol. Biol. 554, 165–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Hirai K., Aliev G., Nunomura A., Fujioka H., Russell R. L., Atwood C. S., Johnson A. B., Kress Y., Vinters H. V., Tabaton M., Shimohama S., Cash A. D., Siedlak S. L., Harris P. L., Jones P. K., Petersen R. B., Perry G., Smith M. A. (2001) Mitochondrial abnormalities in Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurosci. 21, 3017–3023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Keeney P. M., Xie J., Capaldi R. A., Bennett J. P. (2006) Parkinson's disease brain mitochondrial complex I has oxidatively damaged subunits and is functionally impaired and misassembled. J. Neurosci. 26, 5256–5264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Feher J., Kovacs I., Artico M., Cavallotti C., Papale A., Balacco Gabrieli C. (2006) Mitochondrial alterations of retinal pigment epithelium in age-related macular degeneration. Neurobiol. Aging 27, 983–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Poliakov E., Brennan M. L., Macpherson J., Zhang R., Sha W., Narine L., Salomon R. G., Hazen S. L. (2003) Isolevuglandins, a novel class of isoprostenoid derivatives, function as integrated sensors of oxidant stress and are generated by myeloperoxidase in vivo. FASEB J. 17, 2209–2220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Hunt R. C., Davis A. A. (1992) Release of iron by human retinal pigment epithelial cells. J. Cell Physiol. 152, 102–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Ohishi K., Zhang X. M., Moriwaki S., Hiramitsu T., Matsugo S. (2005) Iron release analyses from ferritin by visible light irradiation. Free Radic. Res. 39, 875–882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Yefimova M. G., Jeanny J. C., Guillonneau X., Keller N., Nguyen-Legros J., Sergeant C., Guillou F., Courtois Y. (2000) Iron, ferritin, transferrin, and transferrin receptor in the adult rat retina. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 41, 2343–2351 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Hahn P., Dentchev T., Qian Y., Rouault T., Harris Z. L., Dunaief J. L. (2004) Immunolocalization and regulation of iron handling proteins ferritin and ferroportin in the retina. Mol. Vis. 10, 598–607 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Ohishi K., Zhang X. M., Moriwaki S., Hiramitsu T., Matsugo S. (2006) In the presence of ferritin, visible light induces lipid peroxidation of the porcine photoreceptor outer segment. Free Radic. Res. 40, 799–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Song D., Song Y., Hadziahmetovic M., Zhong Y., Dunaief J. L. (2012) Systemic administration of the iron chelator deferiprone protects against light-induced photoreceptor degeneration in the mouse retina. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 53, 64–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Ortega-Castro J., Frau J., Casasnovas R., Fernández D., Donoso J., Muñoz F. (2012) High- and low-spin Fe(III) complexes of various age inhibitors. J. Phys. Chem. A 116, 2961–2971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Eldred G. E. (1993) Age pigment structure. Nature 364, 396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Sakai N., Decatur J., Nakanishi K., Eldred G. E. (1996) Ocular age pigment “A2-E”: an unprecedented pyridinium bisretinoid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 1559–1560 [Google Scholar]

- 98. Krishnadev N., Meleth A. D., Chew E. Y. (2010) Nutritional supplements for age-related macular degeneration. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 21, 184–189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Clayton P. (2006) B6-responsive disorders: a model of vitamin dependency. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 29, 317–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Galluzzi L., Vacchelli E., Michels J., Garcia P., Kepp O., Senovilla L., Vitale I., Kroemer G. (2013) Effects of vitamin B6 metabolism on oncogenesis, tumor progression and therapeutic responses. Oncogene 10.1038/onc.2012.623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]