Background: Ecm29 binds to proteasome holoenzyme, but its physiological role is poorly understood.

Results: Deletion of Ecm29 rescues proteasomal degradation defects in vivo and increases proteasomal ATPase activity.

Conclusion: Ecm29 is an inhibitor of the proteasome in vivo.

Significance: Ecm29 functions in part by preventing activity of proteasomes that do not pass quality control.

Keywords: ATP-dependent Protease, ATPases, Molecular Chaperone, Protease Inhibitor, Proteasome, Protein Degradation, Ubiquitin-dependent Protease

Abstract

Several proteasome-associated proteins regulate degradation by the 26 S proteasome using the ubiquitin chains that mark most substrates for degradation. The proteasome-associated protein Ecm29, however, has no ubiquitin-binding or modifying activity, and its direct effect on substrate degradation is unclear. Here, we show that Ecm29 acts as a proteasome inhibitor. Besides inhibiting the proteolytic cleavage of peptide substrates in vitro, it inhibits the degradation of ubiquitin-dependent and -independent substrates in vivo. Binding of Ecm29 to the proteasome induces a closed conformation of the substrate entry channel of the core particle. Furthermore, Ecm29 inhibits proteasomal ATPase activity, suggesting that the mechanism of inhibition and gate regulation by Ecm29 is through regulation of the proteasomal ATPases. Consistent with this, we identified through chemical cross-linking that Ecm29 binds to, or in close proximity to, the proteasomal ATPase subunit Rpt5. Additionally, we show that Ecm29 preferentially associates with both mutant and nucleotide depleted proteasomes. We propose that the inhibitory ability of Ecm29 is important for its function as a proteasome quality control factor by ensuring that aberrant proteasomes recognized by Ecm29 are inactive.

Introduction

The proteasome is the major cytosolic protease in eukaryotes. The 26 S proteasome holoenzyme consists of a core particle (CP)3 with one or two regulatory particles (RPs), giving rise to a protease complex of about 2.5 MDa in size. Many proteasome substrates are marked for degradation by the covalent attachment of a polyubiquitin chain (1–3). The first step in degradation is the selection of substrates by a large number of E2 and E3 enzymes that mark specific proteins for degradation. However, additional steps of potential regulation are present at the proteasome. This includes substrate delivery to the proteasome as well as recognition and deubiquitination by the proteasome. These are facilitated by proteasome-intrinsic ubiquitin receptors, like yeast Rpn10 (human PSMD4) and Rpn13 (ADRM1); shuttling factors, like Rad23 (RAD23A/B); and proteasome-associated deubiquitinating enzymes, like Ubp6 (USP14) (1, 4). Finally, substrates require unfolding by the proteasomal AAA-ATPase (the Rpt proteins) and translocation to the inside of the cylindrically shaped CP, where proteolysis occurs.

The ability to inhibit protein degradation by the proteasome using chemical inhibitors of the proteolytic sites has resulted in the development of the Food and Drug Administration-approved treatment of multiple myeloma using the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib (5). In the cell, however, few protein-based proteasome inhibitors have been characterized. In humans, the reported proteasome inhibitors PI31/PSMF1 (6), Rpn14/PAAF1 (7), and S5b/PSMD5 (8) do not directly inhibit the 26 S proteasome. PI31/PSMF1 binds to the CP, competes with RP for CP binding (6), and might have a role in regulating RP-CP association (9). Both Rpn14 and Hsm3, the yeast orthologs of Rpn14/PAAF1 and S5b/PSMD5 respectively, bind to RP and compete with CP for RP binding (10–13). They also have an important role as proteasome-specific chaperones (3, 14). The proteasome is also regulated by posttranslational modifications, which most likely provide an extra level of tuning in its activity (e.g. see Refs. 15 and 16). The closest to a non-chemical inhibitor of the 26 S proteasome currently seems to be Ubp6 (USP14), a deubiquitinating enzyme that interacts with the proteasome (17). This protein delays the degradation of ubiquitinated substrates in part through a mechanism that does not require the deubiquitinating activity (18, 19). Additionally, Ubp6 has been reported to stimulate gate opening in a ubiquitin conjugate-dependent fashion (20). Although the mechanisms of regulation are not well understood, Ubp6 appears to be specific for ubiquitinated substrates. One of the initial screens that identified Ubp6 as a proteasome-associated protein in yeast also identified Ecm29, whose function has remained more elusive (17). Ecm29 and the human ortholog KIAA00368/ECM29 bind specifically to 26 S proteasomes (17, 21). Ecm29 has been reported to stabilize proteasomes (17, 22), to remodel proteasomes upon stress (23, 24), to be involved in membrane-associated localization of proteasomes (21, 25), and, more recently, to be involved in quality control or assembly of the proteasome (23, 26–28). Despite these numerous associations, the molecular effects of Ecm29 binding to the 26 S proteasome remain poorly understood.

In this study, we show that Ecm29 preferentially binds to nucleotide-depleted as well as certain mutant proteasomes. Upon binding to proteasomes, Ecm29 inhibits the in vivo and in vitro degradation of substrates. Binding of Ecm29 to the proteasomes causes a closed gate conformation and, more importantly, causes an inhibition of proteasomal ATPase activity. The latter can explain the observed reduction in in vivo degradation in the presence of Ecm29.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Yeast Strains

See Table 1 for the genotypes of strains used. DNA fragments used to generate C-terminal truncations of Rpt5 at the genomic locus were made by PCR using pYM24 (29) as template and oligonucleotides pRLs2-Rpt5 (AAT ATG TAG ATA TGT GAA TGG CGG CTT GAT AAA TCA AAA TAT TAT TAT TTA TCG ATG AAT TCG AGC TCG) and pRL-s3Rpt5d0 (GTA TAA GTG AAG TTC AAG CAA GAA AAT CGA AAT CGG TAT CCT TTT ATG CAT AGG GCG CGC CAG ATC TGT T) for rpt5-Δ0 (i.e. no truncation control), oligonucleotides pRLs2-Rpt5 and pRL-s3Rpt5d1 (AGG GTA TAA GTG AAG TTC AAG CAA GAA AAT CGA AAT CGG TAT CCT TTT ATT AGG GCG CGC CAG ATC TGT T) for rpt5-Δ1 (i.e. deletion of last amino acid), and oligonucleotides pRLs2-Rpt5 and pRL-s3Rpt5d3 (TCG TTG AGG GTA TAA GTG AAG TTC AAG CAA GAA AAT CGA AAT CGG TAT CCT AGG GCG CGC CAG ATC TGT T) for rpt5-Δ3 (i.e. deletion of last three amino acids). DNA fragments used to exchange the endogenous promoter of ECM29 at the genomic locus were made by PCR using pYM-N15 (29) as template and oligonucleotides pRL194 (TCT CCA CGA GCT GTT TTT CTT TCG CTT CGT CAG AAG AAA TGG ATC CGG AAT GGT GAT GGT GAT GGT GGT GCA TCG ATG AAT TCT CTG TCG) and pfEcm29NtagS1 (CAA TAA TTA TAG AAA AGT TTC TAT TTC ACC ACG AAC AAC ATT CGT ACG CTG CAG GTC GAC). Standard methods for strain construction and cell culture were used. Plating assays were done as described before, using 4-fold dilutions (11).

TABLE 1.

Strains used

| Strain | Genotypea (lys2-801 leu2-3, 2-112 ura3-52 his3-Δ200 trp1-1) | Figures | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| SUB61 | MATα | Figs. 1 (A, B, and D), 2, 3, and 8 | Ref. 60 |

| sDL133 | MATa rpn11::RPN11-TEVProA (HIS3) | Figs. 1C, 6, and 8A | Ref. 17 |

| sDL135 | MATα pre1::PRE1-TEVProA (HIS3) | Fig. 4, A and B | Ref. 17 |

| sMK141 | MATα ecm29::TRP | Figs. 1 (A, B, and D), 2, and 8 | This study |

| sJR211 | MATα ecm29::TRP rpn11::RPN11-TEVProA (HIS3) | Figs. 6 and 8C | This study |

| sJR239 | MATα nas6::TRP rpn14::HYG | Figs. 1 (A, B, and D) and 2 | Ref. 11 |

| sJR245 | MATA hsm3::KAN | Fig. 2 | Ref. 11 |

| sJR301 | MATA nas6::TRP rpn14::HYG ecm29::TRP | Fig. 1 (A, B, and D) and 2 | Ref. 26 |

| sJR494 | MATα α3::α3ΔN α7::α7ΔN | Fig. 4C | Ref. 61 |

| sJR502 | MATα nas2::NAT hsm3::KAN | Figs. 1 (A and D) and 2 | This study |

| sJR504 | MATA rpt5:: RPT5Δ1 (HYG) | Figs. 1 (A and D), 2, and 8 | This study |

| sJR544 | MATα ecm29::TRP rpt5::RPT5Δ3 (HYG) | Figs. 1 (A and D) and 2 | Ref. 26 |

| sJR546 | MATA hsm3::KAN ecm29::TRP rpt5::RPT5Δ3 (HYG) | Figs. 1 (A and D) and 2 | Ref. 26 |

| sJR548 | MATA rpt5::RPT5Δ3 (HYG) ecm29::TRP rpn11::RPN11-TEVProA (HIS3) | Figs. 1C, 5, and 6C | Ref. 26 |

| sJR552 | MATA rpt5::RPT5Δ3 (HYG) rpn11::RPN11-TEVProA (HIS3) | Figs. 1C and 5 | Ref. 26 |

| sJR555 | MATA rpt5::RPT5Δ0 (HYG) | Fig. 8 | Ref. 26 |

| sJR556 | MATA rpt5::RPT5Δ3 (HYG) | Figs. 1 (A, B, and D), 2, and 8 | Ref. 26 |

| sJR558 | MATA hsm3::KAN rpt5::RPT5Δ3 (HYG) | Figs. 1 (A and D) and 2 | Ref. 26 |

| sJR568 | MATA nas2::NAT hsm3::KAN ecm29::TRP | Figs. 1 (A and D) and 2 | This study |

| sJR570 | MATα ecm29::TRP rpt5::RPT5Δ1 (HYG) | Figs. 1 (A and D) and 2 | This study |

| sJR619 | MATA rpn11::RPN11-TEVProA (HIS3) rpt5::RPT5Δ3 (HYG) ecm29::ECM29-HIS7 (KAN) | Fig. 7 | This study |

| sJR649 | MATA rpt5::RPT5Δ3 (HYG) | Fig. 3B | This study |

| sJR651 | MATα ecm29::KAN rpt5::RPT5Δ3 (HYG) | Fig. 3B | This study |

| sJR686b | MATα rpt5::RPT5Δ3 (HYG) α3::α3ΔN α7::α7ΔN | Fig. 4C | This study |

| sJR706 | MATA pre11::PRE1-TEV-ProA (HIS3) α3::α3ΔN | Fig. 4 | This study |

| sJR736 | MATA rpn11::RPN11-TEVProA (HIS3) ecm29::(NAT) pGDP-HIS7-ECM29 | Figs. 6 and 7 | This study |

| sJR743 | MATα α3::α3ΔN α7::α7ΔN ecm29::KAN | Fig. 4C | This study |

| sJR744 | MATα rpt5::RPT5Δ3 (HYG) α3::α3ΔN α7::α7ΔN ecm29::KAN | Fig. 4C | This study |

a All strains have the DF5 background genotype (lys2-801 leu2-3, 2-112 ura3-52 his3-Δ200 trp1-1).

Antibodies

Ecm29 was detected using an Ecm29 polyclonal antibody, kindly provided by Dr. Dan Finley (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA). Rpt4 and Rpt5 were detected using monoclonal anti-Rpt4 and anti-Rpt5, kindly provided by Dr. William Tansey (Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center, Nashville, TN). Monoclonal anti-FLAG (Sigma) was used for detection of FLAG-ornithine decarboxylase (ODC). Monoclonal anti-β-galactosidase antibody (Promega) was used for detection of β-galactosidase. Polyclonal anti-ubiquitin antibody (Enzo) and monoclonal anti-T7 (Novagen) were used for the detection of ubiquitinated substrates, and anti-Pgk1 antibody (Invitrogen) was used as a loading control. Peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were used (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories).

Imaging

All images were acquired using a Gbox imaging system (Syngene) with GeneSnap software. To determine the relative levels of Ecm29 in Fig. 6, peak volumes for the different bands were determined using the Genetool analysis software from Syngene, and values for each Ecm29 signal were corrected for input using the Rpt5 immunoblot. These corrected values were normalized to the signal for ATP without proteasome inhibitor (Fig. 8A) or ecm29Δ with ATP (Fig. 8C). Data shown are the average from 2–4 independent experiments.

FIGURE 6.

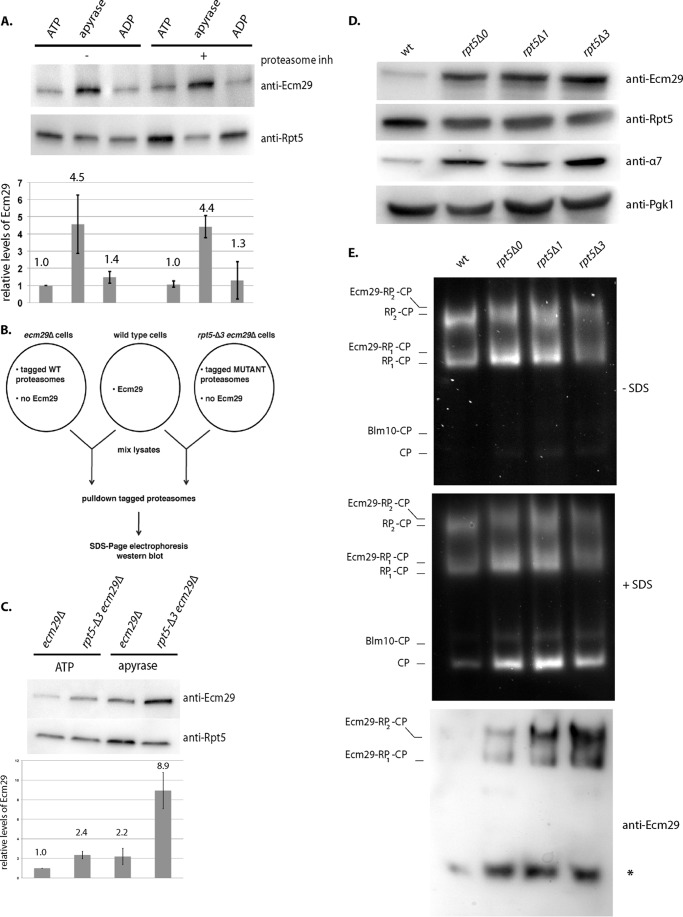

Ecm29 inhibits wild-type proteasomes. A, Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-PAGE analysis of proteasome preparations from the indicated strains that were purified using affinity-tagged lid subunit Rpn11. The bottom panel shows levels of the ATPases subunit Rpt4 by immunoblotting (anti-Rpt4). B, ATPase activity for purifications from A. The activity was determined by measuring ADP produced over time. Data show average ATPase activity with S.D. (error bars) for triplicates of two independent purifications. Activity measurements have been repeated with similar results and are within the range previously reported for proteasomal ATPases. The difference in activity between samples was significant with p < 0.05 as determined by Student's t test. C, purified proteasomes from the indicated strains were incubated with ubiquitinated Sic1PY for the indicated time. Levels of ubiquitinated Sic1PY were determined by immunoblotting using an anti-T7 antibody. The right panel shows quantification of Western blots based on three independent experiments with T = 0 normalized as 100% and S.D. values (error bars) shown. D, overexpression of Ecm29 results in modest canavanine phenotype. Strains with ECM29 deletion or Ecm29 overexpression were spotted on SD plates lacking arginine with or without 1.5 μg/ml canavanine in 4-fold dilutions and grown for 7 days at 30 °C (SD plates). Dilution assays were performed three times with at least two independent clones, each time showing similar growth patterns.

FIGURE 8.

Ecm29 recognizes aberrant proteasomes. A, proteasomes from wild-type cells were purified in the presence of ATP or ADP or in the absence of these nucleotides (apyrase was used to convert endogenous ATP and ADP to AMP), using an affinity tag on the lid subunit Rpn11. Levels of co-purified Ecm29 were determined by immunoblotting for Ecm29 (anti-Ecm29). Proteasome levels were determined using an antibody against the proteasome subunit Rpt5. To show that the enrichment in the absence of nucleotide was not due to proteasomal degradation, the same experiment was performed in the presence of proteasome inhibitors (100 μm Nα-p-tosyl-l-lysine chloromethyl ketone and 100 nm epoxomicin). The table shows relative Ecm29 levels, corrected for input and normalized to lane 1. B, schematic of experiment in C. Wild-type lysates (middle) provide a source of Ecm29 and are mixed with lysates from ecm29Δ cells containing Rpn11-ProA-tagged proteasomes (left) or ecm29Δ rpt5-Δ3 cells containing Rpn11-ProA tagged proteasomes (right). After incubation, proteasomes were affinity-purified using IgG resin, separated on SDS-PAGE, and analyzed. C, experimental scheme, as described in B, was performed in the presence of ATP or in the absence of nucleotide (apyrase). Samples were analyzed for the levels of recruited Ecm29, and Rpt5 was used as a loading control. Results show enriched binding of Ecm29 in the absence of nucleotide as well as to the rpt5-Δ3 proteasomes. The table shows relative Ecm29 levels, corrected for input and normalized to lane 1. D and E, levels of proteasome-associated Ecm29 and total cellular levels. Cultures from wild-type and mutant strains were lysed using a French press. D, whole cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting for the indicated proteins. E, whole cell lysates were subjected to native PAGE electrophoresis in the presence of ATP and stained for Suc-LLVY-AMC hydrolytic activity in the presence or absence of 0.02% SDS. Next, gels were analyzed by Western blot using an anti-Ecm29 antibody. *, nonspecific background band, also observed in the ecm29Δ background. Error bars, S.D.

Proteasome Purifications and Native Gels

The affinity purification of Rpn11- or Pre1-TEV-protein A-tagged proteasomes was performed as described before with minor modifications (17). Briefly, between 1 and 6 liters of overnight cultures (A600 ∼10) were collected, washed in H2O, and resuspended in two pellet volumes of lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8), 1 mm EDTA, 5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm ATP). The cells were lysed by French press, and lysates were cleared by centrifugation (20,000 × g at 4 °C for 25 min). The supernatant was filtered through a cheesecloth, IgG beads (MP Biomedicals) were added (∼0.5 ml/liter of culture), and the lysate was rotated at 4 °C for 1 h. The IgG beads were collected in an Econo Column (Bio-Rad) and washed with ice-cold wash buffer (50 column volumes; 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mm EDTA, 100 mm NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm ATP). Next, beads were washed with 15 column volumes of cleavage buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm DTT, 5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm ATP), followed by cleavage in the same buffer containing His-tagged TEV protease (Invitrogen) for 1 h at 30 °C. Talon beads were added for 20 min at 4 °C to remove TEV protease, after which the preparation was concentrated in a 10-kDa concentrator (Millipore). Proteasome preparations were stored at −80 °C. For the purifications without nucleotide, no ATP was added to any of the solutions. Proteasome preparations were analyzed using standard SDS-PAGE or on native gels prepared as described previously and run between 2 and 3 h at 4 °C (30). Total lysates for analysis on native gel were prepared as described previously (11).

Apyrase Treatment

The apyrase treatment of purified proteasomes was performed as described previously with minor modifications (22). Purified proteasomes were diluted in 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA, and 0.25 mm ATP. Samples were incubated for 45 min at 30 °C with or without apyrase (20 milliunits μl−1 working concentration). After treatment, proteasomes were analyzed using native gels.

β-Galactosidase Assay

Cells were grown overnight in SD medium without lysine and supplemented with 100 μm CuSO4. The cell equivalent to 5 ml of A600 1 was collected, and cells were lysed in 200 μl of breaking buffer (100 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mm DTT, 20% glycerol, 1 mm PMSF) by vortexing in the presence of glass beads. An additional 200 μl of breaking buffer was added and mixed. After centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 5 min, 100 μl of the cleared lysate was mixed with 900 μl of Z buffer (60 mm Na2HPO4, 40 mm NaH2PO4, 10 mm KCl, 1 mm MgSO4, 50 mm β-mercaptoethanol) and incubated for 5 min at 30 °C. After incubation, 200 μl of 4 mg/ml O-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactoside was added to the mixture, followed by an incubation at 30 °C for 30 min. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 500 μl of 1 m Na2CO3. Absorbance was read at 420 nm.

Sic1PY Degradation Assay

1 μg/μl of purified proteasomes (5 μl) were incubated at 25 °C in 15 μl of Buffer A (50 mm Tris (pH 7.5), 100 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mm DTT) plus 10 μl of 5× ATP (10 mm ATP, 50 mm MgCl2, 5 mm DTT in Buffer A) for 5 min. 20 μl of T7-tagged ubiquitinated Sic1PY was added to each sample (prepared as described by Saeki et al. (31)), and incubation at 25 °C continued for the indicated times. At each time point, 10-μl aliquots were taken, and the reaction was stopped by the addition of 6× sample buffer and boiling. To quantify data, images were acquired using a Gbox imaging system (Syngene) with GeneSnap software. Images were analyzed for the volumes in similar T7 antibody-positive areas of the gel lanes using the Genetool analysis software from Syngene. The volume value at t = 0 was set at 100%, and relative amounts of signal remaining at different time points were averaged, using 3–5 independent experiments, and plotted in a graph.

Cell Lysis, in Vivo Degradation Assay, and Immunoblotting

For detection of ubiquitinated substrates, cultures were grown overnight, and the cell equivalent to 5 ml of A600 1 was collected and lysed in 100 μl of sample buffer and analyzed by SDS-PAGE, using a 14% gel. Degradation of FLAG-ODC was measured as described previously (32), with minor modifications. Briefly, transformed cells were grown overnight; the cell equivalent to 5 ml of A600 was lysed in sample buffer and analyzed on 10% SDS-PAGE. FLAG-ODC abundance was revealed by Western blot.

Ecm29 Recruitment Assay

4 ml of overnight culture pellets from strains, with and without proteasome tags, were lysed in 400 μl of total lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8), 5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA, protease inhibitor mix) in the presence of ATP or apyrase. To purify the proteasomes, lysates were incubated with IgG resin for 1 h at 4 °C. The resin was washed three times with lysis buffer with or without ATP, followed by two washes with TEV buffer (50 mm Tris (pH 7.5), 50 mm NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 0.5 mm EDTA, 1 mm DTT) with or without ATP. Next, the resin was incubated in the presence of TEV protease for 30 min at 30 °C. After centrifugation, sample buffer was added to the supernatant, boiled, and analyzed by Western blot. To look at the degradation of Ecm29 by wild-type proteasomes, the same procedure was followed with the addition of proteasome inhibitors, 100 μm Nα-p-tosyl-l-lysine chloromethyl ketone and 100 nm epoxomicin (ENZO Life Sciences).

ATPase Activity Assay

Purified proteasomes (10 μg) were incubated in reaction buffer (50 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 5 mm MgCl2) and 0.5 mm ATP at 30 °C in a total reaction volume of 100 μl. For each time point, 20 μl of the reaction was taken, boiled for 2.5 min, and kept on ice. After all of the time points were collected, the samples were centrifuged at room temperature at 13,000 × g for 1 min. An ADP-Glo kinase (Promega, CA) assay was performed following the manufacturer's recommendations and using a 384-well plate. 5 μl of each sample was incubated with 5 μl of ADP-Glo reagent for 40 min at room temperature. Following this incubation, 10 μl of kinase detection reagent was added to each sample and incubated for 60 min at room temperature. Luminescence was read using a Victor 2 Microplate Reader (PerkinElmer Life Sciences).

Cross-linking

Purified proteasomes (1 μg/μl) were incubated in phosphate buffer (50 mm phosphate buffer (pH 7.2), 5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm ATP) with 0.25 mm disuccinimidyl tartarate for 15 min at 30 °C. The reaction was quenched by adding 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), followed by the addition of 200 μl of urea buffer (8 m urea, 300 mm NaCl, 100 mm phosphate buffer (pH 7.9)). 25 μl of Talon resin (pre-equilibrated in urea buffer) was added to each sample, followed by a 45-min rotation at room temperature. Resin was washed three times with urea buffer. 25 μl of 2× sample buffer was added, and each sample was boiled for 8 min prior to analysis by gel electrophoresis.

RESULTS

Ecm29 Inhibits Degradation of Ubiquitinated Substrates

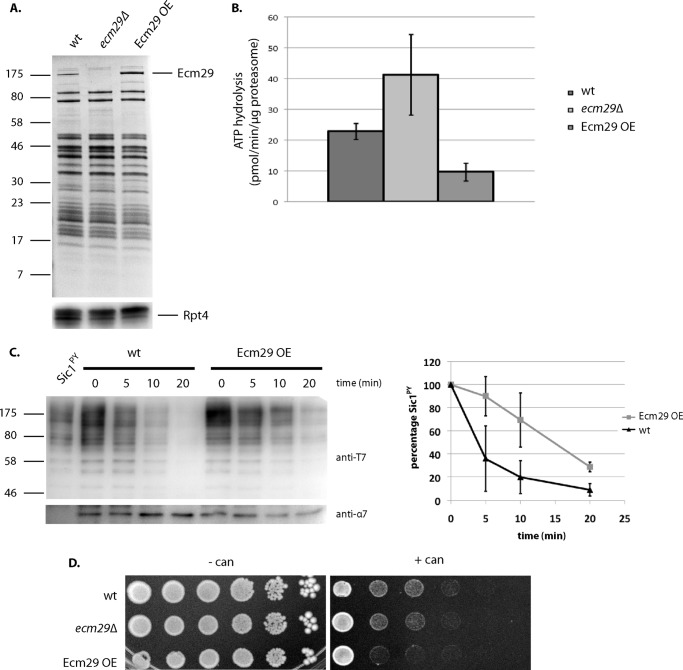

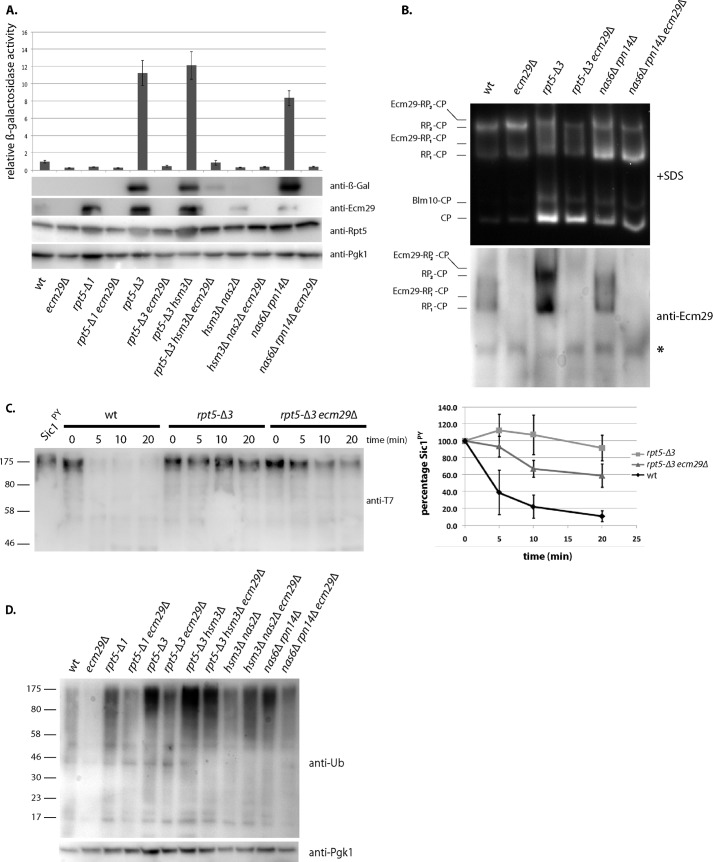

In vitro, the presence of Ecm29 causes reduced hydrolysis of the artificial peptide substrate Suc-LLVY-AMC by the 26 S proteasome (23, 26). Therefore, we speculated that Ecm29 functions as an inhibitor of the 26 S proteasome inside the cell. To test this, we transformed a wild-type strain and an ECM29 deletion strain (ecm29Δ) with a plasmid encoding the well characterized unstable substrate ubi-K-β-galactosidase (33). Although we saw a trend of reduced accumulation of β-galactosidase activity in lysates of ecm29Δ cells, this reduction was not significant (Fig. 1A). However, because only a subset of proteasomes contain Ecm29 in wild-type cells (23, 26, 27), any Ecm29-dependent effects may be masked. Therefore, we decided to utilize a previously characterized proteasome hypomorph, the rpt5-Δ3 strain, in which 26 S proteasomes are enriched with Ecm29 (Fig. 1B) (26). The mutation in this strain results in a deletion of the last three amino acids of the proteasomal AAA-ATPase subunit Rpt5. These residues are important for Rpt5 binding to the CP (34, 35) as well as the RP chaperone Nas2 (26). Their absence conferred canavanine sensitivity, typically observed in proteasome hypomorphs (Fig. 2). rpt5-Δ3 mutants showed accumulation of β-galactosidase and high levels of β-galactosidase activity in total lysate (Fig. 1A), indicating reduced proteasome activity in these cells. Deletion of Ecm29 from rpt5-Δ3 mutants alleviated the degradation defect (Fig. 1A, lanes 5 and 6). Because the deletion of Ecm29 did not result in increased proteasome levels (Fig. 1A, αRpt5) and Ecm29 was bound to 26 S proteasomes (Fig. 1B) (26), this strongly suggests that inhibition of proteasomes by Ecm29 in the rpt5-Δ3 background contributed to the accumulation of β-galactosidase activity. To confirm that the observed inhibition by Ecm29 is a direct effect on proteasomal degradation of ubiquitinated proteins, we analyzed the ability of wild-type, rpt5-Δ3, and rpt5-Δ3 ecm29Δ-derived proteasomes to degrade ubiquitinated Sic1PY in vitro (31). rpt5-Δ3-derived proteasomes showed a dramatic reduction in their capacity to degrade this substrate, and the absence of Ecm29 restored the degradation of ubiquitinated Sic1PY, although not back to the levels of wild-type proteasomes (Fig. 1C) (see below).

FIGURE 1.

Ecm29 inhibits the degradation of ubiquitinated proteins in vivo and in vitro. A, the indicated strains were transformed with an unstable form of the enzyme β-galactosidase (Ub-K-βgal). β-Galactosidase activity was measured in lysates, and activities relative to wild type were plotted (top panel). S.D. values (error bars) were determined using three independent experiments. The bottom panels show levels of β-galactosidase enzyme using immunoblotting (anti-β-Gal), levels of Ecm29 (anti-Ecm29), proteasome levels (anti-Rpt5), and a loading control (anti-Pgk1). B, cultures from the indicated strains were lysed using a French press. Whole cell lysates were subjected to native PAGE electrophoresis in the presence of ATP and stained for Suc-LLVY-AMC hydrolytic activity in the presence of 0.02% SDS. Gels were analyzed by Western blot using an anti-Ecm29 antibody. *, nonspecific background band. C, purified proteasomes were incubated with ubiquitinated Sic1PY for the indicated time. Levels of ubiquitinated Sic1PY remaining were determined by immunoblotting using an anti-T7 antibody. The right panel shows quantification of Western blot based on three independent experiments with T = 0 normalized as 100% and S.D. values shown (error bars). D, whole cell lysates from wild-type and mutant strains were analyzed by Western blot using an anti-ubiquitin antibody.

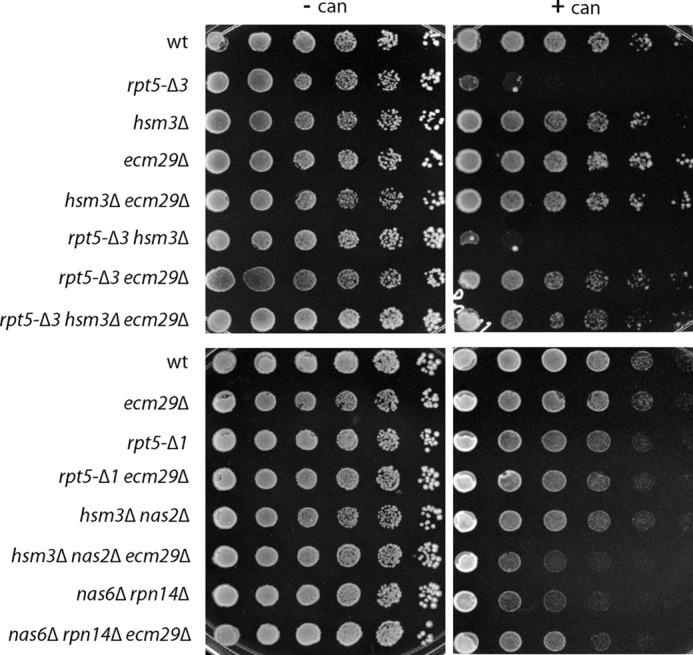

FIGURE 2.

Deletion of Ecm29 rescues canavanine sensitivity of proteasome mutants. Strains with the indicated mutations or genes deleted were spotted in 4-fold dilutions on arginine-lacking SD plates with or without 1.5 μg/ml canavanine and grown at 30 °C for 7 days. Dilution assays were performed in triplicates for two or more independent clones, each showing similar growth patterns.

To determine if the observed inhibition by Ecm29 is specific for this proteasome hypomorph or is a more general phenomenon, we tested the nas6Δ rpn14Δ strain. This strain, which contains deletions for two RP chaperones involved in assembly of the proteasome base, showed canavanine sensitivity (Fig. 2) (11) and exhibited an enrichment of Ecm29 on 26 S proteasomes (Fig. 1B). nas6Δ rpn14Δ cells showed an accumulation of β-galactosidase compared with wild type (Fig. 1A), and deletion of ECM29 in this background reduced β-galactosidase levels. Thus, Ecm29 can inhibit proteasomes in a variety of mutant strains.

Like the majority of proteasome substrates, ubi-K-β-galactosidase relies on ubiquitination for its targeting to and degradation by the proteasome. When blotting for ubiquitinated proteins in total lysate, we observed a general accumulation of ubiquitinated material in the proteasome hypomorphs (Fig. 1D). The deletion of ECM29 in these different backgrounds strongly reduced the levels of accumulated ubiquitinated proteins, indicating that Ecm29 inhibited the degradation of a broad range of endogenous ubiquitinated substrates inside the cell (Fig. 1D). Interestingly, this effect was also observed for wild-type cells deleted for ECM29. This suggests that Ecm29 inhibits at least a subset of wild-type proteasomes under normal physiological conditions as well.

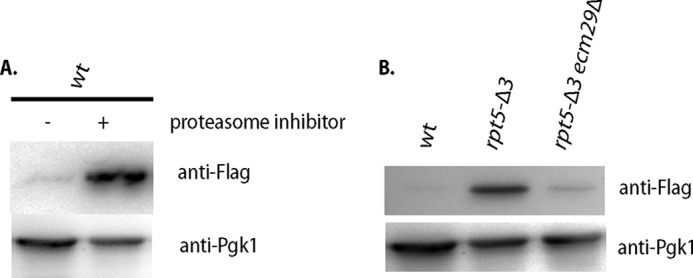

Ecm29 Inhibits Degradation of the Ubiquitin-independent Substrate ODC

If inhibition of the proteasome is specific for ubiquitinated proteins, as has been reported for Ubp6 (18), Ecm29 could potentially be interfering with the delivery or processing of ubiquitinated substrates instead of inhibiting proteasomes more directly. Therefore, we tested the ability of the rpt5-Δ3 and rpt5-Δ3 ecm29Δ strains to degrade an established, short lived, ubiquitin-independent substrate, ODC (32, 36, 37). We transformed strains with a plasmid containing a FLAG-tagged version of mouse ODC (32) and determined the steady-state level of ODC (Fig. 3, A and B). As expected, ODC was barely detectable in lysates from wild-type cells. However, it accumulated in rpt5-Δ3 lysates or upon treatment with proteasome inhibitors at concentrations that inhibit proteasome activity in wild-type cells (38) (Fig. 3, A and B). Deleting ECM29 in the rpt5-Δ3 background strongly reduced the accumulation of ODC (Fig. 3B), albeit not back to wild-type levels. The latter finding suggests that the rpt5-Δ3 proteasomes have an intrinsic degradation defect. This is consistent with the observations in the in vitro degradation assay (Fig. 1C) as well as the residual accumulation of ubiquitinated material in total lysate of rpt5-Δ3 ecm29Δ cells compared with wild-type cells (Fig. 1D). Nevertheless, the presence of Ecm29 is a major contributor to the reduced capacity of rpt5-Δ3 cells to degrade ODC.

FIGURE 3.

Ecm29 inhibits protein degradation of ubiquitin-independent substrates in vivo. A, wild-type cells transformed with a plasmid expressing FLAG-tagged mouse ODC were inoculated at A600 ∼0.5 and grown for 6 h in the presence or absence of proteasome inhibitor (100 μm PS-341), lysed, and analyzed for the levels of ODC by immunoblotting using anti-FLAG. B, the indicated strains were transformed with a plasmid expressing FLAG-tagged mouse ODC, grown overnight, and lysed, and steady state levels of ODC were determined by immunoblotting with an anti-FLAG antibody.

To assess the role of Ecm29 under proteasome stress conditions in vivo, we tested canavanine sensitivity for the different strains. Canavanine is an analog of arginine that leads to misfolding of proteins upon incorporation into nascent proteins. To handle the extra protein folding stress, cells show an increased dependence on molecular chaperones and the activity of the protein degradation machinery. The mutants that accumulated β-galactosidase (Fig. 1A), like the rpt5-Δ3 and the nas6Δ rpn14Δ strains, also displayed increased sensitivity to canavanine (Fig. 2). Deletion of ECM29 in these backgrounds reduced the sensitivity to canavanine, consistent with a role for Ecm29 as a proteasome inhibitor in the cell (Fig. 2). Note that for certain proteasome-related mutants, like nas2Δ hsm3Δ (Fig. 2) and blm10Δ (39), canavanine sensitivity is actually augmented by the deletion of ECM29. This pleiotropic effect most likely indicates additional roles performed by Ecm29 in the cell (see “Discussion”). Nevertheless, the rescue of canavanine sensitivity by the deletion of ECM29 reiterates the point that, besides the proteasomal mutations themselves, Ecm29 is a major contributor to degradation defects in certain mutants.

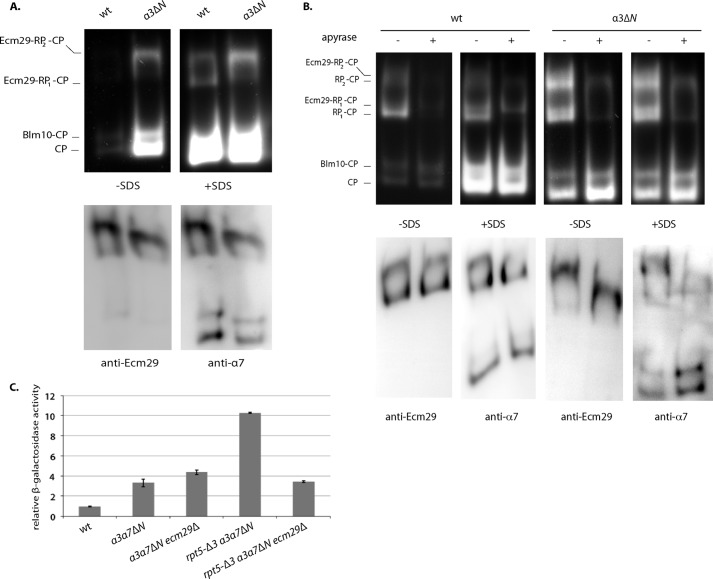

In Vitro Inhibition of Degradation Requires the CP Gate

We have previously reported that in vitro the Ecm29-dependent inhibition of Suc-LLVY-AMC peptide cleavage was eliminated by the addition of 0.02% SDS (26). For free CP, this level of SDS has been shown to open the CP gate required for substrate entry (40), suggesting that Ecm29 prevents full opening of this gate. To test this directly, we used a mutant with a (partial) open gate, the α3ΔN strain (40). A proteasome purification in the presence of ATP yields 26 S proteasomes with and without Ecm29. In yeast, only Ecm29-containing proteasomes are stable in the absence of ADP and ATP (17, 22, 26). Therefore, to obtain only Ecm29-containing 26 S proteasomes, we purified proteasomes in the absence of nucleotide (Fig. 4A) or treated proteasomes purified in the presence of ATP with apyrase, which hydrolysis ATP and ADP (Fig. 4B). All of the resulting 26 S proteasomes (Fig. 4, A and B (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8)) contain Ecm29. As seen before, wild-type Ecm29-containing 26 S proteasomes are inhibited, because they do not show activity in the absence of SDS (Fig. 4, A (lane 1) and B (lane 2)). However, Ecm29-containing 26 S proteasomes from the open gate mutant are active (compare Fig. 4, A (lanes 1 and 2) and B (lanes 2 and 6)), indicating that Ecm29-dependent inhibition requires a functional CP gate. Immunoblotting for Ecm29 and CP subunit α7 as well as the hydrolytic assay in the presence of SDS showed that similar levels of 26 S proteasome were present in the native gel. In sum, Ecm29 inhibition of Suc-LLVY-AMC hydrolysis depends on a functional CP gate, indicating that binding of Ecm29 to 26 S proteasomes reduces the time these proteasomes spend in an open gate conformation.

FIGURE 4.

The open gate mutant rescues Ecm29-dependent inhibition of Suc-LLVY-AMC hydrolytic activity in vitro but not the Ecm29-dependent inhibition of in vivo substrates. A, proteasomes were affinity-purified from strains with tagged CP subunit in the absence of ATP to ensure that all 26 S proteasomes are associated with Ecm29 (22). The samples were subjected to native gel electrophoresis in the presence of ATP and stained for Suc-LLVY-AMC hydrolytic activity in the presence or absence of 0.02% SDS. Ecm29 containing 26 S proteasomes from the open gate mutant (α3ΔN), but not wild-type cells, shows Suc-LLVY-AMC hydrolytic activity in the absence of SDS. The addition of SDS shows that both preparations contain 26 S proteasomes with Suc-LLVY-AMC hydrolytic capacity. Immunoblotting of the native gels for Ecm29 and the CP subunit α7 show equal amounts of Ecm29 on the proteasome preparations. B, proteasomes were affinity-purified from strains with tagged CP subunit in the presence of ATP. To visualize the difference between RP-CP species with or without Ecm29, samples were treated with apyrase to remove all ATP and ADP. In apyrase-treated samples, all 26 S proteasomes are associated with Ecm29, as shown previously (22, 26). The samples were subjected to native gel electrophoresis in the presence of ATP and stained for Suc-LLVY-AMC hydrolytic activity in the presence or absence of 0.02% SDS. Wild-type and mutant proteasomes show reduced 26 S activity upon apyrase treatment, because only a small fraction of proteasomes contain Ecm29. Wild-type Ecm29-containing proteasomes have reduced activity in the absence of SDS (top panel, compare lanes 2 and 4). The open gate (α3ΔN) Ecm29-containing proteasomes do not show increased activity upon the addition of SDS (compare lanes 6 and 8), indicating that in vitro Ecm29 requires a functional gate for inhibition of Suc-LLVY-AMC hydrolysis. Immunoblotting of native gels for Ecm29 and the CP subunit α7 shows equal amounts of Ecm29 on the proteasome preparations with or without apyrase treatment. C, open gate mutant (α3ΔN α7ΔN) does not rescue the accumulation of β-galactosidase as a result of the rpt5-Δ3 mutations. The assay was identical to that shown in Fig. 1A. Error bars, S.D.

To test if Ecm29 in vivo mainly acts through regulation of the gate, we compared accumulation of the unstable substrate β-galactosidase (see Fig. 1A) in an open gate mutant strain with or without the rpt5-Δ3 mutation. To ensure maximal disruption of the gate, we used a strain containing deletions of the N terminus of two α subunits, both α3 and α7 (40). The increased accumulation of substrate in the rpt5-Δ3 background was Ecm29-dependent (Fig. 4C). Thus, in vivo the inhibition by Ecm29 is not eliminated by disruption of the CP gate, indicating that Ecm29 inhibits proteasomes through a gate-independent mechanism as well.

Ecm29 Reduces Proteasomal ATPase Activity of rpt5-Δ3

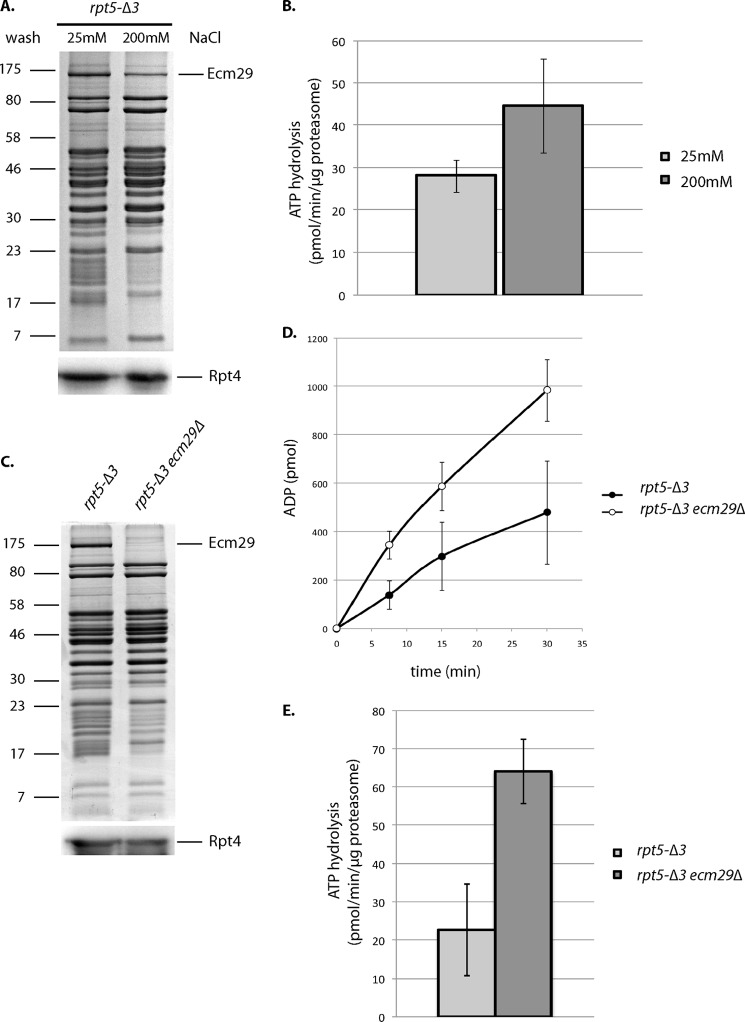

Unlike peptide substrates, the degradation of folded protein substrates in vivo as well as in vitro is ATP-dependent. Therefore, we tested if Ecm29 affects proteasomal ATPase activity. We purified proteasomes from rpt5-Δ3 cells using a wash step with 25 or 200 mm NaCl (Fig. 5A). The high salt wash reduces Ecm29 levels, because the proteasomal association of Ecm29 is salt-sensitive (17, 23). Consistent with the reported role of Ecm29 as a stabilizer of 26 S proteasomes (17, 22), proteasomes with reduced levels of Ecm29 showed reduced amounts of CP subunits (Fig. 5A, bands between 17 and 23 kDa). However, the level of proteasomal ATPases was similar (Fig. 5A, bottom). Proteasome preparations washed with 200 mm NaCl showed an increased ATPase activity (Fig. 5B). This suggests that the presence of Ecm29 inhibits the proteasomal ATPase activity. To further test this, we purified proteasomes from rpt5-Δ3 and rpt5-Δ3 ecm29Δ strains under low salt conditions. As expected, the deletion of Ecm29 resulted in less CP (Fig. 5C, bands between 17 and 23 kDa). SDS-PAGE analysis, immunoblotting, and mass spectrometry analysis show, however, similar levels of RP and proteasomal ATPase subunits (Fig. 5C and Table 2). To measure the ATPase activity from these preparations, we again measured ADP production over time (Fig. 5D). As shown in Fig. 5E, we observed increased ATPase activity in proteasome preparations that lack Ecm29. The mass spectrometry analysis does not show any other ATPases in the sample that could explain the difference in ATPase activity (Table 2). Furthermore, the observed ATPase activity shows reversed correlation with the amount of Ecm29 present (Fig. 5), and the observed ATPase activities are within the same range as reported by others for proteasomal ATPase activity (41). Therefore, our data strongly suggest that Ecm29 directly or indirectly inhibits proteasomal ATPases.

FIGURE 5.

Ecm29 inhibits proteasomal ATPase activity from rpt5-Δ3-derived proteasomes. A, Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-PAGE analysis of proteasome preparations that were purified using affinity-tagged lid subunit Rpn11 and washed with buffer containing different concentrations of NaCl. The bottom panel shows levels of the ATPases subunit Rpt4 by immunoblotting (anti-Rpt4). B, ATPase activity for purifications from A. The activity was determined by measuring ADP produced over time. Data show average ATPase activity with S.D. (error bars) for triplicates of two independent purifications. Activity measurements have been repeated with similar results. Difference in activity was significant with p < 0.05 as determined by Student's t test. C, Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-PAGE analysis of proteasome preparations that were purified using affinity-tagged lid subunit Rpn11. The bottom panel shows levels of the ATPase subunit Rpt4 by immunoblotting (anti-Rpt4). D and E, ATPase activity for purifications from C. The activity was determined by measuring ADP produced over time. Data show average ATPase activity with S.D. for triplicates of two independent purifications. Activity measurements have been repeated with similar results and are within the range previously reported for proteasomal ATPases (41). Difference in activity was significant with p < 0.05 as determined by Student's t test.

TABLE 2.

Peptide numbers for proteins identified by mass spectrometry

| Name | Alternative name | Molecular mass | rpt5-Δ3 | rpt5-Δ3 ecm29Δ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Da | ||||

| Ecm29 | ECM29_YEAST | 211,610 | 89 | 0 |

| α1 | SCL1_YEAST | 25,759 | 23 | 11 |

| α2 | PRE8_YEAST | 27,145 | 12 | 5 |

| α3 | PRE9_YEAST | 31,688 | 10 | 4 |

| α4 | PRE6_YEAST | 28,697 | 15 | |

| α5 | PUP2_YEAST | 28,770 | 21 | 5 |

| α6 | PRE5_YEAST | 28,154 | ||

| α7 | PRE10_YEAST | 28,650 | 10 | |

| β1 | PRE3_YEAST | 26,968 | 17 | 3 |

| β2 | PUP1_YEAST | 22,560 | 6 | |

| β3 | PUP3_YEAST | 22,819 | 6 | |

| β4 | PRE1_YEAST | 29,425 | 20 | 6 |

| β5 | PRE2_YEAST | 31,902 | 11 | 6 |

| β6 | PRE7_YEAST | 23,761 | 15 | 3 |

| β7 | PRE4_YEAST | 28,650 | 4 | 4 |

| Rpt1 | CIM5_YEAST | 52,293 | 27 | 24 |

| Rpt2 | YTA5_YEAST | 49,026 | 17 | 12 |

| Rpt3 | YTA2_YEAST | 47,864 | 22 | 17 |

| Rpt4 | SUG2_YEAST | 49,492 | 15 | 13 |

| Rpt5 | YTA1_YEAST | 48,283 | 26 | 22 |

| Rpt6 | SUG1_YEAST | 45,471 | 20 | 14 |

| Rpn1 | RPN1_YEAST | 109,880 | 52 | 51 |

| Rpn2 | RPN2_YEAST | 104,623 | 58 | 55 |

| Rpn3 | RPN3_YEAST | 60,754 | 29 | 24 |

| Rpn5 | RPN5_YEAST | 51,850 | 29 | 16 |

| Rpn6 | RPN6_YEAST | 50,085 | 31 | 26 |

| Rpn7 | RPN7_YEAST | 49,213 | 29 | 16 |

| Rpn8 | RPN8_YEAST | 38,460 | 25 | 20 |

| Rpn9 | RPN9_YEAST | 45,811 | 31 | 27 |

| Rpn10 | RPN10_YEAST | 29,786 | 13 | 7 |

| Rpn11 | RPN11_YEAST | 34,433 | 19 | 11 |

| Rpn12 | RPN12_YEAST | 31,956 | 26 | 15 |

| Rpn13 | RPN13_YEAST | 18,005 | 6 | 7 |

| Nas6 | NAS6_YEAST | 25,616 | 12 | 10 |

| Ubp6 | UBP6_YEAST | 57,110 | 40 | 27 |

| Hul5 | HUL5_YEAST | 105,564 | 16 | 8 |

| Ssa2 | SSA2_YEAST | 69,469 | 4 | 5 |

| Hsp70 | 63,400 | 2 | 0 |

Ecm29 Inhibits Wild-type Proteasomes

Because we relied on proteasome mutants for the enrichment of Ecm29 onto proteasomes, the observed effects might be unique for the specific mutant used. The reduced accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins in total lysate of the ecm29Δ strain suggests, however, that Ecm29 has the same effect on wild-type cells (Fig. 1C). To test this more rigorously, we generated a strain that strongly overexpresses Ecm29 by replacing the endogenous promoter with the GPD promoter (29). This has been shown to cause increased Ecm29 levels on wild-type proteasomes (23). Next, we affinity-purified proteasomes from an ecm29Δ strain, a strain with the endogenous promoter, or a strain overexpressing Ecm29 (Fig. 6A). The ATPase activity measured in these purifications again showed a reversed correlation with Ecm29 levels present; the ecm29Δ-derived proteasomes showed increased ATPase activity, and the purifications with increased levels of Ecm29 showed reduced ATPase activity (Fig. 6B). Thus, the association of Ecm29 with proteasomes results in reduced ATPase activity independent of the presence of proteasome mutations. To test if the increased presence of Ecm29 on wild-type proteasomes also results in degradation defects, we measured, as we did for rpt5-Δ3-derived proteasomes (Fig. 1C), the ability of wild-type proteasomes enriched in Ecm29 to degrade ubiquitinated Sic1PY. Consistent with a function as inhibitor of the proteasome, we observed slower degradation of Sic1PY in the presence of Ecm29 (Fig. 6C). The overexpression of Ecm29 also caused modest canavanine sensitivity (Fig. 6D). These data further confirm that the presence of Ecm29 on proteasomes results in reduced ATPase activity and interferes with the ability of proteasomes to degrade substrates.

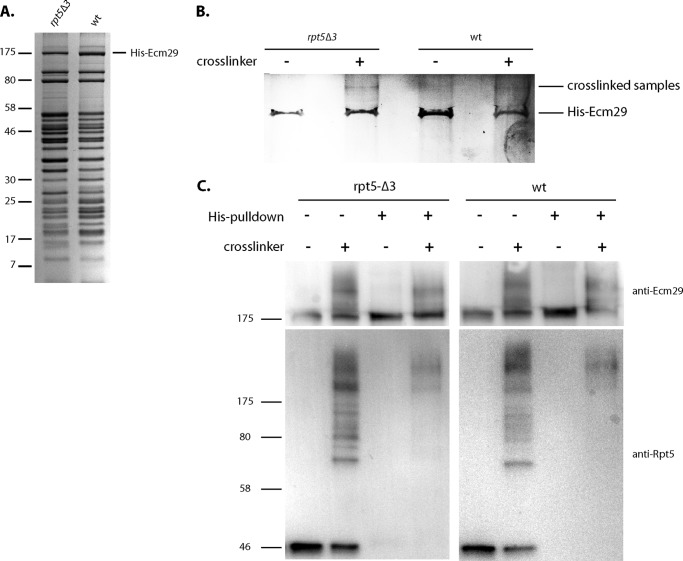

Ecm29 Binds Close to the Regulatory Particle Subunit Rpt5

Ecm29 has been proposed to bind to CP as well as RP; however, no detailed binding information is available for Ecm29 (17). To identify a proteasomal binding site for Ecm29, we generated a strain that contains an N-terminally His-tagged Ecm29 in a background containing the Rpn11-TEV-ProA with or without the rpt5-Δ3 mutation. Proteasomes purified from both strains using the Rpn11-ProA tag show a similar subunit composition and the presence of Ecm29 (Fig. 7A). To identify a direct binding partner or proteasome subunit in close proximity of Ecm29, we treated the purified proteasomes with cross-linker (disuccinimidyl tartarate, 6.4-Å spacer arm length). Samples with or without cross-linking were denatured in 8 m urea, and His-Ecm29 was purified under denaturing conditions. Samples were resolved on SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Blue (Fig. 7B). Lanes 2 and 4 specifically show slower migrating bands, probably indicating Ecm29 cross-linked to a proteasome subunit. Mass spectrometry analysis of gel regions with cross-linked material revealed the presence of Ecm29 and Rpt5 in lanes 2 and 4 but not lanes 1 or 3 or a control sample that was cross-linked but lacked His-tagged Ecm29. Western blot analysis of the different steps in the procedure confirmed Rpt5 cross-linking to Ecm29 (Fig. 7C). Considering the moderate levels of cross-linking (Fig. 7, B and C), the cross-linking between Rpt5 and Ecm29 is probably direct. This is also consistent with previous work detecting more Ecm29 in proteasomes purified using tagged Rpt5 (42). In sum, our data show that Ecm29 either binds Rpt5 directly or binds in close proximity to Rpt5.

FIGURE 7.

Ecm29 binds close to the AAA-ATPase subunit Rpt5. A, Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-PAGE analysis of proteasome preparations from the indicated strains that were purified using affinity-tagged lid subunit Rpn11. B, samples from A were treated with the cross-linker disuccinimidyl tartarate or DMSO and denatured in 8 m urea, and His-Ecm29 was purified using Talon resin. Sample was resolved on gel and stained with Coomassie Blue. C, immunoblots are shown for Rpt5 and Ecm29 in the different steps of the cross-linking procedure. Lanes 2 and 6 show Rpt5, as would be expected, cross-linked to several different proteasome subunit. Cross-linking was not excessive because ∼50% of the Rpt5 was not cross-linked; hence, amounts of indirect cross-linking should be low. The purification under denaturing conditions in lanes 4 and 8 show the specific cross-linking to Ecm29.

Ecm29 Recruitment to the Proteasome

The enrichment of Ecm29 on mutant proteasomes can in part be explained by increased expression of Ecm29 under proteasome stress conditions (23). However, this cannot explain why we consistently observed an increased presence of Ecm29 on proteasomes purified in the absence of nucleotide as compared with proteasomes purified with ATP present (Fig. 8A; apyrase was used to remove endogenous ATP and ADP from lysates). This difference cannot be explained by ATP-dependent degradation of Ecm29 during the purification, because this accumulation was not observed in the presence of ADP or in the presence of proteasome inhibitors (Fig. 8A). Thus, Ecm29 appears to be specifically recruited to proteasomes with most or all ATPase subunits in a nucleotide-empty state.

To test if Ecm29 enrichment on proteasomes in specific strains, like the rpt5-Δ3, can be explained in part by a preferential binding of Ecm29 to such proteasomes, we tried to purify Ecm29 from bacteria. However, bacterially expressed full-length Ecm29 was unstable and not competent in binding to proteasomes; therefore, we used a lysate of wild-type yeast cells as our source of Ecm29. To test if this Ecm29 has a preference for binding to certain proteasomes, we looked at the recruitment to affinity-tagged proteasomes from wild-type or rpt5-Δ3 strains deleted for ECM29 (Fig. 8B). We observed that more Ecm29 associated with rpt5-Δ3-derived proteasomes as compared with the wild type (Fig. 8C). Treatment with apyrase enhanced the amount of Ecm29 bound to wild type as well as rpt5-Δ3-derived proteasomes but retained the Ecm29 preference for mutant proteasomes (Fig. 8C). Strong overexpression of Ecm29 can also yield increased Ecm29 levels on wild-type proteasomes (23) (Fig. 6), suggesting that the subtle difference in affinity regulates Ecm29 abundance on proteasomes. Consistent with this, more modest overexpression of Ecm29, like we observed in our control or Rpt5 truncated strains (Fig. 8D), only shows a modest increase of proteasome-associated Ecm29 in the control strain, whereas there is a strong increase for the Rpt5 truncation strains (Fig. 8E). In all, these experiments show that Ecm29 preferentially binds to nucleotide-depleted proteasomes as well as rpt5-Δ3-derived proteasomes.

DISCUSSION

Since its discovery as proteasome-associated protein over 10 years ago, many functions have been proposed for Ecm29. This probably indicates that Ecm29 has multiple functions inside the cell. Consistent with this, the deletion of ECM29 in the different mutant strains shows pleiotropic effects. As mentioned under “Results,” canavanine sensitivity can either be augmented or rescued when ECM29 is deleted. For temperature stress, the deletion of ECM29 has been observed to increase (e.g. ump1Δ strain (27)) as well as rescue (e.g. the rpt6-Δ1 or the nas2Δ hsm3Δ strains (23, 26)) temperature sensitivity. Interestingly, for the nas2Δ hsm3Δ strain, deletion of Ecm29 shows a very robust rescue of the temperature sensitivity (26), whereas at the same time, it shows a modest increase in canavanine sensitivity (Fig. 3). Clearly, different phenotypes in specific mutants each highlight a different cellular function of Ecm29.

In this study, we utilized a proteasome hypomorph, the rpt5-Δ3 strain, to study the function of Ecm29 in cells, because Ecm29 is highly enriched on 26 S proteasomes in this strain (26). Surprisingly, our data show that the proteasomal degradation defect in this proteasome hypomorph is only partly due to the mutation of the proteasome subunit Rpt5. The increased presence of Ecm29 on proteasomes in this strain is a major contributor to this strain's inability to degrade proteasome substrates. Several other proteasome mutants also show an increase in Ecm29-bound proteasomes (23, 27). Because the mutations to proteasome subunits probably cause the formation of aberrant proteasomes, Ecm29 might have a more common role as inhibitor of proteasome activity for certain aberrant forms of the proteasome.

Proteasomal Recruitment of Ecm29

How would Ecm29 be able to be enriched on a variety of proteasome mutants, whereas in wild-type cells only a subset of proteasomes are associated with Ecm29 (22, 23, 26–28)? One proposed model suggests that Ecm29 is degraded by the proteasome (27). If proteasome mutants have reduced proteolytic activity, Ecm29 would then accumulate. This model is supported by the observation that affinity-tagged Ecm29 is unstable (27, 28). However, untagged Ecm29 has been reported to be stable (23), suggesting an alternative mechanism for Ecm29 enrichment on proteasomes. A second model proposes that an increase in the ratio Ecm29 versus proteasomes in specific proteasome mutants is a determining factor in proteasomal association of Ecm29 (23). Consistent with this, the overexpression of ECM29 from a very strong promoter increases the association of Ecm29 with wild-type proteasomes (Fig. 6) (23). However, this model provides little dynamic control if Ecm29 is a stable protein and seems counterintuitive, considering the inhibitory function described here. Furthermore, such a model cannot explain the preferential binding we observe (Fig. 8C) or the increase in Ecm29 recruitment upon oxidative stress (24). We propose that an important component of the recruitment of Ecm29 to proteasomes relies on the ability of Ecm29 to recognize, directly or indirectly, certain aberrant conformations of the proteasome.

Mutants in RP as well as CP have been shown to cause increased Ecm29 association. It seems unlikely that Ecm29 would be able to recognize differences in the conformation induced by proteasome mutants located at distant or opposite sites of the proteasome. We speculate that Ecm29 does not recognize each mutant specifically, but all of these mutants cause a similar unfavorable alignment between CP and RP that results in increased affinity for Ecm29 to proteasomes. For certain mutants, like rpt5-Δ3 or rpt6-Δ1, it is clear that they affect the CP-RP interface, because the C-terminal residues deleted in these mutants dock into pockets located on the α ring surface of the CP and contribute the to RP-CP interaction (13, 34, 35, 43–47). Ecm29 also has been reported to recognize RP-CP species in which CP maturation is stalled (27). Ecm29 might recognize those by a different mechanism, because, at first glance, it appears unlikely that stalled CP maturation affects the RP-CP interface. However, the proteolytic active sites of the CP have been shown to allosterically affect the RP-CP interface (22, 48). This suggests that certain CP mutations or the level of CP maturation could affect the conformation of the RP-CP interface.

The model that Ecm29 recognizes differences at the CP-RP interface is also supported by the observed increase in binding of Ecm29 to nucleotide-depleted proteasomes (Fig. 8). Under normal conditions, only two of the proteasomal AAA-ATPase subunits have been suggested to be free of nucleotides (49). The lack of more nucleotides probably causes a different conformation of the ATPase ring that abuts the CP, because the lack of nucleotide is known to destabilize the RP-CP interaction (22). The increased association of Ecm29 with nucleotide-depleted proteasomes suggests that Ecm29 recognizes such proteasomes prior to the RP-CP dissociation. Another protein showing nucleotide-dependent binding is AIRAP. This protein is not present in yeast, but Caenorhabditis elegans AIRAP has been shown to preferably bind and stabilize nucleotide-depleted proteasomes (50). However, unlike Ecm29, AIRAP seems to increase Suc-LLVY-AMC hydrolytic activity of the proteasomes with which it associates (50).

Our cross-linking of Ecm29 to Rpt5 is consistent with the model we propose as well as with recent cryo-EM structures of the proteasome. The latter show that Rpt5 is accessible for binding (51–54). Considering the large size of Ecm29 (210 kDa) and the unique binding properties (only binds to 26 S proteasomes), we expect that Ecm29 will interact with additional proteasome subunits. Identifying the other proteasomal binding sites of Ecm29 will further establish how the specificity of binding by Ecm29 is achieved.

The recruitment of Ecm29 to certain aberrant proteasomes fits well with previous reports proposing a function as a quality control protein (26, 27). A tantalizing model is that the inhibition of the proteasome is an important component of the Ecm29 quality control function, because it prevents proteolysis by aberrant proteasomes from occurring inside the cell. Next, such proteasomes would have to be either corrected or targeted for degradation (e.g. by the lysosome). The former has been suggested (27), whereas the latter might provide a connection to other proposed functions of Ecm29 by linking it to endosomes and transport motors (21, 25). Clearly, a better understanding of the fate of Ecm29-bound proteasomes will be crucial to understand the role of Ecm29 in proteasome assembly, quality control, and regulation.

Mechanism of Inhibition by Ecm29

Because recent EM structures of the proteasome (51–54) indicate that access to the CP gate is shielded by the Rpt subunits, it seems unlikely that Ecm29 can directly inhibit CP gate opening. Our data show that Ecm29 binds to the proteasome in close proximity to Rpt5. Thus, Ecm29 might restrict the conformational freedom of one or several of the proteasomal Rpt proteins, thereby causing reduced ATPase activity. The binding to Rpt5 might also cause closing of the CP gate, because the Rpt proteins abut the CP and are known to regulate gate opening (34, 35, 43, 44). Furthermore, mutations disrupting ATP binding or hydrolysis in yeast and mammalian proteasomal ATPases have been shown to affect gating and protein degradation (55–57). Alternatively, binding of Ecm29 to the CP directly might induce an allosteric closing of the gate. In this scenario, the inhibition of ATPase activity and gate closing are two independent events induced by Ecm29 binding to RP and CP, respectively.

Understanding the mechanism of Ecm29-proteasome interactions might provide us with new targets in the search for alternative proteasome inhibitors and shows, as had previously been shown with USP14, that targeting the RP has the potential for the development of pharmaceuticals (19, 58). More intriguingly, the realization that Ecm29 is an in vivo inhibitor of proteasome activity might provide new clues about the reduced proteasome activity observed in certain neurodegenerative diseases and during aging (59). It will be interesting to see if there is increased binding of KIAA00368/ECM29 to proteasomes in such conditions.

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Coffino, W. Tansey, and D. Finley for materials and Y. Azuma, M. Zolkiewski, M. Hochstrasser, members of the Roelofs laboratory, and members of the Lee laboratory for helpful discussions. We thank S. Peck, E. Cain, and M. Kleijnen for critically reading the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants 5P20 RR017708 and P20 RR016475 (from the National Center for Research Resources) and 8 P20 GM103420 and P20 GM103418 (from NIGMS). This work was also supported by the Johnson Cancer Research Center.

- CP

- core particle

- RP

- regulatory particle

- ODC

- ornithine decarboxylase

- Suc-

- succinimidyl-

- AMC

- 7-amido-4-methylcoumarin.

REFERENCES

- 1. Finley D. (2009) Recognition and processing of ubiquitin-protein conjugates by the proteasome. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 477–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schrader E. K., Harstad K. G., Matouschek A. (2009) Targeting proteins for degradation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 815–822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tomko R. J., Jr., Hochstrasser M. (2013) Molecular Architecture and Assembly of the eukaryotic Proteasome. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 82, 415–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu C. W., Jacobson A. D. (2013) Functions of the 19S complex in proteasomal degradation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 38, 103–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Orlowski R. Z., Kuhn D. J. (2008) Proteasome inhibitors in cancer therapy. Lessons from the first decade. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 1649–1657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McCutchen-Maloney S. L. (2000) cDNA cloning, expression, and functional characterization of PI31, a proline-rich inhibitor of the proteasome. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 18557–18565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Park Y., Hwang Y. P., Lee J. S., Seo S. H., Yoon S. K., Yoon J. B. (2005) Proteasomal ATPase-associated factor 1 negatively regulates proteasome activity by interacting with proteasomal ATPases. Mol. Cell Biol. 25, 3842–3853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shim S. M., Lee W. J., Kim Y., Chang J. W., Song S., Jung Y. K. (2012) Role of S5b/PSMD5 in proteasome inhibition caused by TNF-α/NFκB in higher eukaryotes. Cell Rep. 2, 603–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cho-Park P. F., Steller H. (2013) Proteasome regulation by ADP-ribosylation. Cell 153, 614–627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Park S., Roelofs J., Kim W., Robert J., Schmidt M., Gygi S. P., Finley D. (2009) Hexameric assembly of the proteasomal ATPases is templated through their C termini. Nature 459, 866–870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Roelofs J., Park S., Haas W., Tian G., McAllister F. E., Huo Y., Lee B. H., Zhang F., Shi Y., Gygi S. P., Finley D. (2009) Chaperone-mediated pathway of proteasome regulatory particle assembly. Nature 459, 861–865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Barrault M. B., Richet N., Godard C., Murciano B., Le Tallec B., Rousseau E., Legrand P., Charbonnier J. B., Le Du M. H., Guérois R., Ochsenbein F., Peyroche A. (2012) Dual functions of the Hsm3 protein in chaperoning and scaffolding regulatory particle subunits during the proteasome assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, E1001–E1010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Park S., Li X., Kim H. M., Singh C. R., Tian G., Hoyt M. A., Lovell S., Battaile K. P., Zolkiewski M., Coffino P., Roelofs J., Cheng Y., Finley D. (2013) Reconfiguration of the proteasome during chaperone-mediated assembly. Nature 497, 512–516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bedford L., Paine S., Sheppard P. W., Mayer R. J., Roelofs J. (2010) Assembly, structure, and function of the 26S proteasome. Trends Cell Biol. 20, 391–401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Guo X., Engel J. L., Xiao J., Tagliabracci V. S., Wang X., Huang L., Dixon J. E. (2011) UBLCP1 is a 26S proteasome phosphatase that regulates nuclear proteasome activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 18649–18654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Um J. W., Im E., Park J., Oh Y., Min B., Lee H. J., Yoon J. B., Chung K. C. (2010) ASK1 negatively regulates the 26 S proteasome. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 36434–36446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Leggett D. S., Hanna J., Borodovsky A., Crosas B., Schmidt M., Baker R. T., Walz T., Ploegh H., Finley D. (2002) Multiple associated proteins regulate proteasome structure and function. Mol. Cell 10, 495–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hanna J., Hathaway N. A., Tone Y., Crosas B., Elsasser S., Kirkpatrick D. S., Leggett D. S., Gygi S. P., King R. W., Finley D. (2006) Deubiquitinating enzyme Ubp6 functions noncatalytically to delay proteasomal degradation. Cell 127, 99–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee B.-H., Lee M. J., Park S., Oh D.-C., Elsasser S., Chen P.-C., Gartner C., Dimova N., Hanna J., Gygi S. P., Wilson S. M., King R. W., Finley D. (2010) Enhancement of proteasome activity by a small-molecule inhibitor of USP14. Nature 467, 179–184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Peth A., Besche H. C., Goldberg A. L. (2009) Ubiquitinated proteins activate the proteasome by binding to Usp14/Ubp6, which causes 20S gate opening. Mol. Cell 36, 794–804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gorbea C., Goellner G. M., Teter K., Holmes R. K., Rechsteiner M. (2004) Characterization of mammalian Ecm29, a 26 S proteasome-associated protein that localizes to the nucleus and membrane vesicles. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 54849–54861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kleijnen M. F., Roelofs J., Park S., Hathaway N. A., Glickman M., King R. W., Finley D. (2007) Stability of the proteasome can be regulated allosterically through engagement of its proteolytic active sites. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 1180–1188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Park S., Kim W., Tian G., Gygi S. P., Finley D. (2011) Structural defects in the regulatory particle-core particle interface of the proteasome induce a novel proteasome stress response. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 36652–36666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang X., Yen J., Kaiser P., Huang L. (2010) Regulation of the 26S Proteasome Complex During Oxidative Stress. Sci. Signal. 3, ra88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gorbea C., Pratt G., Ustrell V., Bell R., Sahasrabudhe S., Hughes R. E., Rechsteiner M. (2010) A protein interaction network for Ecm29 links the 26 S proteasome to molecular motors and endosomal components. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 31616–31633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lee S. Y., De la Mota-Peynado A., Roelofs J. (2011) Loss of Rpt5 protein interactions with the core particle and Nas2 protein causes the formation of faulty proteasomes that are inhibited by Ecm29 protein. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 36641–36651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lehmann A., Niewienda A., Jechow K., Janek K., Enenkel C. (2010) Ecm29 fulfils quality control functions in proteasome assembly. Mol. Cell 38, 879–888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Panasenko O. O., Collart M. A. (2011) Not4 E3 ligase contributes to proteasome assembly and functional integrity in part through Ecm29. Mol. Cell. Biol. 31, 1610–1623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Janke C., Magiera M. M., Rathfelder N., Taxis C., Reber S., Maekawa H., Moreno-Borchart A., Doenges G., Schwob E., Schiebel E., Knop M. (2004) A versatile toolbox for PCR-based tagging of yeast genes. New fluorescent proteins, more markers and promoter substitution cassettes. Yeast 21, 947–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Elsasser S., Schmidt M., Finley D. (2005) Characterization of the proteasome using native gel electrophoresis. Methods Enzymol. 398, 353–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Saeki Y., Isono E., Toh-E A. (2005) Preparation of ubiquitinated substrates by the PY motif-insertion method for monitoring 26S proteasome activity. Methods Enzymol. 399, 215–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Erales J., Hoyt M. A., Troll F., Coffino P. (2012) Functional asymmetries of proteasome translocase pore. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 18535–18543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bachmair A., Finley D., Varshavsky A. (1986) In vivo half-life of a protein is a function of its amino-terminal residue. Science 234, 179–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gillette T. G., Kumar B., Thompson D., Slaughter C. A., DeMartino G. N. (2008) Differential roles of the COOH termini of AAA subunits of PA700 (19 S regulator) in asymmetric assembly and activation of the 26 S proteasome. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 31813–31822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Smith D. M., Chang S.-C., Park S., Finley D., Cheng Y., Goldberg A. L. (2007) Docking of the proteasomal ATPases' carboxyl termini in the 20S proteasome's α ring opens the gate for substrate entry. Mol. Cell 27, 731–744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gandre S., Kahana C. (2002) Degradation of ornithine decarboxylase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is ubiquitin independent. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 293, 139–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Murakami Y., Matsufuji S., Kameji T., Hayashi S., Igarashi K., Tamura T., Tanaka K., Ichihara A. (1992) Ornithine decarboxylase is degraded by the 26S proteasome without ubiquitination. Nature 360, 597–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fleming J. A., Lightcap E. S., Sadis S., Thoroddsen V., Bulawa C. E., Blackman R. K. (2002) Complementary whole-genome technologies reveal the cellular response to proteasome inhibition by PS-341. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 1461–1466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schmidt M., Haas W., Crosas B., Santamaria P. G., Gygi S. P., Walz T., Finley D. (2005) The HEAT repeat protein Blm10 regulates the yeast proteasome by capping the core particle. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 294–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Groll M., Bajorek M., Köhler A., Moroder L., Rubin D. M., Huber R., Glickman M. H., Finley D. (2000) A gated channel into the proteasome core particle. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7, 1062–1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Henderson A., Erales J., Hoyt M. A., Coffino P. (2011) Dependence of proteasome processing rate on substrate unfolding. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 17495–17502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Guerrero C., Tagwerker C., Kaiser P., Huang L. (2006) An integrated mass spectrometry-based proteomic approach. Quantitative analysis of tandem affinity-purified in vivo cross-linked protein complexes (QTAX) to decipher the 26 S proteasome-interacting network. Mol. Cell Proteomics 5, 366–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Stadtmueller B. M., Ferrell K., Whitby F. G., Heroux A., Robinson H., Myszka D. G., Hill C. P. (2010) Structural models for interactions between the 20S proteasome and its PAN/19S activators. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 13–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rabl J., Smith D. M., Yu Y., Chang S.-C., Goldberg A. L., Cheng Y. (2008) Mechanism of gate opening in the 20S proteasome by the proteasomal ATPases. Mol. Cell 30, 360–368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lander G. C., Martin A., Nogales E. (2013) The proteasome under the microscope. The regulatory particle in focus. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 23, 243–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Matyskiela M. E., Lander G. C., Martin A. (2013) Conformational switching of the 26S proteasome enables substrate degradation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 20, 781–788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tian G., Park S., Lee M. J., Huck B., McAllister F., Hill C. P., Gygi S. P., Finley D. (2011) An asymmetric interface between the regulatory and core particles of the proteasome. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18, 1259–1267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Osmulski P. A., Hochstrasser M., Gaczynska M. (2009) A tetrahedral transition state at the active sites of the 20S proteasome is coupled to opening of the α-ring channel. Structure 17, 1137–1147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Smith D. M., Fraga H., Reis C., Kafri G., Goldberg A. L. (2011) ATP binds to proteasomal ATPases in pairs with distinct functional effects, implying an ordered reaction cycle. Cell 144, 526–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Stanhill A., Haynes C. M., Zhang Y., Min G., Steele M. C., Kalinina J., Martinez E., Pickart C. M., Kong X. P., Ron D. (2006) An arsenite-inducible 19S regulatory particle-associated protein adapts proteasomes to proteotoxicity. Mol. Cell 23, 875–885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Beck F., Unverdorben P., Bohn S., Schweitzer A., Pfeifer G., Sakata E., Nickell S., Plitzko J. M., Villa E., Baumeister W., Förster F. (2012) Near-atomic resolution structural model of the yeast 26S proteasome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 14870–14875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. da Fonseca P. C., He J., Morris E. P. (2012) Molecular model of the human 26S proteasome. Mol. Cell 46, 54–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lander G. C., Estrin E., Matyskiela M. E., Bashore C., Nogales E., Martin A. (2012) Complete subunit architecture of the proteasome regulatory particle. Nature 482, 186–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lasker K., Förster F., Bohn S., Walzthoeni T., Villa E., Unverdorben P., Beck F., Aebersold R., Sali A., Baumeister W. (2012) Molecular architecture of the 26S proteasome holocomplex determined by an integrative approach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 1380–1387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kim Y. C., Li X., Thompson D., DeMartino G. N. (2013) ATP-binding by proteasomal ATPases regulates cellular assembly and substrate-induced functions of the 26S proteasome. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 3334–3345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rubin D. M., Glickman M. H., Larsen C. N., Dhruvakumar S., Finley D. (1998) Active site mutants in the six regulatory particle ATPases reveal multiple roles for ATP in the proteasome. EMBO J. 17, 4909–4919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lee S. H., Moon J. H., Yoon S. K., Yoon J. B. (2012) Stable incorporation of ATPase subunits into 19 S regulatory particle of human proteasome requires nucleotide binding and C-terminal tails. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 9269–9279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. D'Arcy P., Brnjic S., Olofsson M. H., Fryknäs M., Lindsten K., De Cesare M., Perego P., Sadeghi B., Hassan M., Larsson R., Linder S. (2011) Inhibition of proteasome deubiquitinating activity as a new cancer therapy. Nat. Med. 17, 1636–1640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kourtis N., Tavernarakis N. (2011) Cellular stress response pathways and ageing. Intricate molecular relationships. EMBO J. 30, 2520–2531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Finley D., Ozkaynak E., Varshavsky A. (1987) The yeast polyubiquitin gene is essential for resistance to high temperatures, starvation, and other stresses. Cell 48, 1035–1046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Bajorek M., Finley D., Glickman M. H. (2003) Proteasome disassembly and downregulation is correlated with viability during stationary phase. Curr. Biol. 13, 1140–1144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]