Abstract

Dengue Virus (DV) infects between 50 and 100 million people globally, with public health costs totaling in the billions. It is the causative agent of dengue fever (DF) and dengue hemorrhagic fever/dengue shock syndrome (DHF/DSS), vector-borne diseases that initially predominated in the tropics. Due to the expansion of its mosquito vector, Aedes spp., DV is increasingly becoming a global problem. Infected individuals may present with a wide spectrum of symptoms, spanning from a mild febrile to a life-threatening illness, which may include thrombocytopenia, leucopenia, hepatomegaly, hemorrhaging, plasma leakage and shock. Deciphering the underlining mechanisms responsible for these symptoms has been hindered by the limited availability of animal models that can induce classic human pathology. Currently, several permissive non-human primate (NHP) species and mouse breeds susceptible to adapted DV strains are available. Though virus replication occurs in these animals, none of them recapitulate the cardinal features of human symptomatology, with disease only occasionally observed in NHPs. Recently our group established a DV serotype 2 intravenous infection model with the Indian rhesus macaque, which reliably produced cutaneous hemorrhages after primary virus exposure. Further manipulation of experimental parameters (virus strain, immune cell expansion, depletion, etc.) can refine this model and expand its relevance to human DF. Future goals include applying this model to elucidate the role of pre-existing immunity upon secondary infection and immunopathogenesis. Of note, virus titers in primates in vivo and in vitro, even with our model, have been consistently 1000-fold lower than those found in humans. We submit that an improved model, capable of demonstrating severe pathogenesis may only be achieved with higher virus loads. Nonetheless, our DV coagulopathy disease model is valuable for the study of select pathomechanisms and testing DV drug and vaccine candidates.

Keywords: dengue virus, disease pathogenesis, non-human primate, hemorrhage, platelet, bone marrow, platelet-lymphocyte aggregate, rhesus macaque

Introduction

Dengue Virus (DV), the causative agent of dengue fever (DF), is the most important vector-borne human pathogen, infecting between 50 and 100 million people annually (Who, 2012). Moreover, DF is an escalating human problem that is increasingly spreading across the globe and extending in seasonality. This recent growth is attributed to the expansion in the niche of the virus-transmitting vectors, primarily Aedes albopictus and Aedes aegypti (Who, 2011). Thanks to the lack of vector control, increased human travel and global warming, DF, once considered a tropical disease, may reach a worldwide distribution.

The majority of DV infections are asymptomatic or mild, but for about a quarter of infected people, disease may present as an illness that is indistinguishable from other febrile diseases or as DF with minor hemorrhagic abnormalities, bone pain, decreases in platelet counts and leucopenia, the most common form of disease. Rarely, people present with the severe forms—dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) in which patients display hematomas with a marked thrombocytopenia or extremely low platelet counts and dengue shock syndrome (DSS), a disease similar to DHF but including plasma leakage/heme concentration, pleural effusion and the increased risk of multi-organ failure (Who and Tdr, 2009). Other symptoms (abnormal bleeding, melena, hepatomegaly, vomiting, etc.) have also been reported (Cobra et al., 1995). The majority of severe DHF/DSS cases in endemic countries occur in healthy adolescents 10–24 years of age (Tsai et al., 2012). Early identification of the causative agent and immediate hydration therapy with extensive monitoring of symptoms is important for resolving symptoms and preventing fatal outcomes (Who and Tdr, 2009). There is currently no targeted therapy to modulate disease severity of those most vulnerable.

It has been surmised that factors such as genetic susceptibility, developmental stage, environmental exposures and immune system programming induced by previous infections may predispose young adults to more severe disease (Halstead et al., 2007). Epidemiological data obtained from endemic countries reveal that DHF/DSS most often occurs in people with a secondary antibody response, which has led many to champion the antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) of infection hypothesis (Endy et al., 2004; Fox et al., 2011). ADE proponents believe that weakly specific, cross-reacting antibodies facilitate virus entry into permissive cells, increasing titers and thus, disease. Though some ADE proponents suggest that dengue-specific antibody increases immunopathology without necessarily enhancing virus replication (Markoff et al., 1991; Lei et al., 2001; Oishi et al., 2003). On the contrary, many reports have failed to demonstrate an association of DHF/DSS with secondary infection (Murgue et al., 1999, 2000; Cordeiro et al., 2007; Guilarde et al., 2008; Libraty et al., 2009; Meltzer et al., 2012). A better association may exist between virus titers and disease severity (Murgue et al., 2000; Libraty et al., 2002). Despite the uncertainty over ADE, it is required that this potential risk factor be considered during the formulation of all vaccines under development (Who, 2011). Standard preventative modalities incorporate representative antigens of each serotype in effort to simultaneously induce protection to all four DV strains.

In the past, vaccines were designed without an exact understanding of the mechanism(s) responsible for disease pathogenesis; this was done by selecting for candidates that reduced viremia and elicited strong antibody responses (Cox, 1953; Togo, 1964). Unfortunately this approach has failed with DV, a pathogen that does not elicit strong humoral immunity in natural infections. Neutralizing antibody to DV can be elicited in a variety of primates (chimpanzees, cynomolgus macaques, African green monkeys, etc.) after primary infection, but they are often weak and short-lived (Scherer et al., 1978; Bernardo et al., 2008; Martin et al., 2009). In addition, protection from viremia has been reported in rhesus macaques that develop poor neutralizing antibody titers (Scott et al., 1980; Putnak et al., 1996) and after the response waned (Raviprakash et al., 2000). Interestingly, some evidence suggests that humans may also be protected from disease during high viremia without ever developing specific antibodies (Stramer et al., 2012; Perng and Chokephaibulkit, 2013); these observations raise concern that neutralizing antibody quantification is not the best approach to evaluate vaccine efficacy.

A more thorough understanding of the mechanisms contributing to disease and protection in humans is clearly needed to accelerate progress toward better drug and vaccine candidates. Severe disease is known to arise after the clearance of viremia, suggesting that DHF/DSS and lethality are more likely immune than viral-mediated (Who and Tdr, 2009). In fact, immune activities elicited via antibodies (Saito et al., 2004), complement (Avirutnan et al., 2006) and T cells (Green et al., 1999) have been associated with disease in human studies. Importantly, the delay in severe disease presentation until late after infection limits our ability to interrogate early events that set the stage for immunopathogenesis. Thrombocytopenia, plasma leakage, and coagulation abnormalities appear to be the critical phenomena to prevent in patients, but the events preceding these phenomena have been incompletely elucidated. Carefully controlled experiments performed in relevant animal models are needed to explore the dynamics of hematological dysfunction and other factors potentially involved in dengue disease. Unfortunately an adequate animal model that is capable of recapitulating human disease is largely unavailable.

Development of DV infection animal model systems

The search for animal model systems began in the early 1900s, far before the availability of cell culture techniques to propagate or quantify virus stocks. Pathogens had to be amplified in animals that were permissive and quantified by mortality studies. Unfortunately none of the animals tested (hamster, mouse, rat, lizard, etc.) ever displayed signs of disease, limiting the progress in studying DV (Simmons et al., 1931). The research that was conducted often involved virus propagation in human volunteers, who suffered from typical DF (Simmons et al., 1931). Eventually, a young suckling mouse model inoculated intracranially with DV that displayed mild disease was developed (Sabin and Schlesinger, 1945). This model was quite limited, with paralysis observed only after 3–4 weeks in 10–20% of the mice, but this provided a starting point for virus adaptation and lead to the first small animal infection model.

Mouse model

There are a number of mouse breeds that have been employed in DV investigations–wildtype, engrafted-SCID, AG129, RAG-hu, and the NOD/SCID/IL-2Rγ/human CD34 transplant or humanized mouse (Lin et al., 1998; Kuruvilla et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2007; Mota and Rico-Hesse, 2011; Zompi et al., 2011). AG129 mice have been the most commonly utilized strain; they are highly susceptible to dengue, replicate virus to high titers and display vascular leakage (Shresta et al., 2006; Zompi and Harris, 2012). The NOD/SCID/IL-2Rγ mice reconstituted with human CD34+ cells are infrequently used but have the greatest potential as future mouse models. These animals demonstrate several symptoms of human disease (fever, erythema, thrombocytopenia) (Mota and Rico-Hesse, 2011; Cox et al., 2012).

However, the symptomatology observed with inbred, immune-compromised mice differs from that seen in humans, likely because of the susceptibility of various cell lineages and the extensive differences in immune system dynamics (Nussenblatt et al., 2010). AG129 mice predominantly display neurological symptoms and splenomegaly (Schul et al., 2007; Zompi and Harris, 2012) and engrafted-SCID mice present with paralysis (Zompi and Harris, 2012). While the humanized mouse may be the closest to replicating patient pathology, there still remain a few caveats to using this model. Challenges involved in humanized mouse preparation and data interpretation are compounded by the considerable mouse-to-mouse variation observed (Akkina et al., 2011). Additionally this mouse model, with murine stroma and endothelium, cannot completely mimic the immune response of humans. A number of mechanisms suspected to play critical roles in dengue pathology are differentially regulated in these mice. Processes that are dependent on stromal cell interactions, such as B lymphocyte maturation and specific antibody production (Akkina, 2013), and involve endothelial microparticle signaling, such as the coagulation cascade (Mairuhu et al., 2003; Lynch, 2007), may unfold differently in these mice and lead to alternative outcomes. The human CD34+ engrafted mouse model system can provide a great starting point in interpreting important biological processes involved in human DV disease but results will still need to be confirmed in non-human primate (NHP) species.

Non-human primate (NHP) models

It has been hypothesized that the close genetic relationship between primates and humans and the presence of a comparable immune responses make NHPs the best models for studying DV. While this may be, NHPs have been particularly unreliable at modeling DV pathology, producing mild symptoms at best (Scherer et al., 1972; Halstead et al., 1973b). Monkeys thus far appear to be incapable of succumbing to life-threatening DV disease. However, several Old and New World primate species are in fact permissive to experimental DV infection (Scherer et al., 1978; Schiavetta et al., 2003; Onlamoon et al., 2010; Yoshida et al., 2012). A recently published review detailed the characteristics of viremia in many of these species (Hanley et al., 2013). Table 1 summarizes the pathology and immunopathology observed thus far in ~20 NHP species from 15 different genera.

Table 1.

Summary of in vivo DV studies.

| Primate | Route | Strain | Type | Virus stocka | Doseb | Infected | Viremiac | Findings (source) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macaca mulatta | iv, sc | ND | ND | Humans | ND | ND | ND | No disease, leucopenia (Lavinder and Francis, 1914) |

| Macaca cyclopis | sc, iv, ip | ND | ND | Humans | ND | ND | ND | No disease (Koizumi and Tonomura, 1917) |

| Macaca mulatta | NI | ND | ND | Humans | ND | Yes | ND | Animal chilly and morose, rash on chin, and throat (Chandler and Rice, 1923) |

| Macaca fascicularis | sc | ND | ND | Humans | ND | Yes | ND | First to demonstrate unquestionably that some primates were permissive to DV |

| Cercopithecus callitrichus | ND | ND | Humans | ND | Yes | ND | infection but that they are asymptomatic | |

| Papio spp. | ND | ND | Humans | ND | No | ND | ||

| Cercocebus spp. | ND | ND | Humans | ND | No | ND | (Blanc et al., 1929) | |

| Macaca mulatta | sc, mi | ND | ND | Humans, mosquitoes | ND | No | ND | |

| Macaca fascicularis philippinensis | sc, mi, ic | ND | ND | Humans, mosquitoes | ND | Yes | ND | No fever, some leukopenia and lymphocytosis, demonstrated transmission of DV from primates to humans through mosquitoes |

| Macaca fascicularis fusca* | sc, mi | ND | ND | Humans, mosquitoes | ND | Yes | ND | (Simmons et al., 1931) |

| Pan troglodytes* | sc, id | Hawaiian | NI | Human | ND | Yes | ND | Mild fever (101°F) (Paul et al., 1948) |

| Homo sapiens | id | NI | NI | Human | 1d | Yes | + | Low dose gave multiple patterns of disease: (1) unmodified attack, (2) short febrile illness without rash or 3) no illness but partial immunity |

| id | 10d | Yes | + | Progression of symptoms:(1) edema and erythema, (2) fever, (3) maculopapular eruptions with sparing at the site of the original skin lesion | ||||

| into scars | Conc. human serum | Yes | + | Unmodified dengue | ||||

| eye | 2E5d | Yes | + | Typical dengue | ||||

| eye | 1E4d | No | − | No disease or immunity | ||||

| in | 1E6d | Yes | + | Unmodified dengue or mild rash | ||||

| in | 1E4d | No | − | No disease or immunity (Sabin, 1952) | ||||

| Cebus capucinus | sc or ip | Hawaiian, NGC | DV1, DV2 | Human | ND | Yes | + | No overt signs of illness |

| Ateles geoffroyi | Yes | + | ||||||

| Ateles fusciceps | Yes | + | ||||||

| Alouatta palliata | Yes | + | ||||||

| Callithrix geoffroyi* | Yes | ND | ||||||

| Saimiri oerstedii | Yes | ND | ||||||

| Aotus trivirgatus | Yes | ND | (Rosen, 1958) | |||||

| Hylobates lar | sc | BKM725-67 | DV1 | LLC-MK2 | 800 | Yes | + | Fever and hemorrhagic manifestations occurred but were associated with acute |

| BKM1179-67 | DV1 | 800 | Lymphomatous leukemia, no correlation between antibody titers to | |||||

| BKM1749 | DV2 | 1.6E3 | DV and protection from viremia | |||||

| 24969 | DV3 | 6.6E2 | ||||||

| KS168-68 | DV4 | 5E3 | (Whitehead et al., 1970) | |||||

| Saimiri sciureus | sc | Hawaii | DV1 | Mice | 1E6.4e | Yes | + | Some fever in DV1 infection, |

| 16007 | DV1 | LLC-MK2 | 1E5.7 | Yes | − | No platelet, hematocrit or leukocyte count changes | ||

| NGC | DV2 | Mice | 1E6.7e | Yes | + | |||

| NGC | DV2 | mosquitoes | 1E2.5 | Yes | + | |||

| 16681 | DV2 | LLC-MK2 | 1E5.5 | Yes | − | |||

| Pak-20 | DV3 | LLC-MK2 | 1E3.4 | Yes | 50 | |||

| 16562 | DV3 | LLC-MK2 | 1E5.7 | Yes | − | |||

| 4328S | DV4 | LLC-MK2 | 1E3.9 | No | − | |||

| Saguinus oedipus | sc | Hawaii | DV1 | Mice | 1E6.4e | Yes | + | Brief fever in DV1 infection |

| NGC | DV2 | Mice | 1E6.7e | Yes | + | |||

| NGC | DV2 | Mosquitoes | 1E2.5 | Yes | + | |||

| H87 | DV3 | Mice | 1E5.8 | Yes | − | |||

| Pak-20 | DV3 | LLC-MK2 | 1E3.4 | Yes | − | |||

| H241 | DV4 | Mice | 1E6.6e | No | − | |||

| Saimiri sciureus | in | Hawaii | DV1 | Mice | 1E6.4e | Yes | ND | No disease reported |

| NGC | DV2 | Mice | 1E5e | No | ND | |||

| NGC | DV2 | mosquitoes | 1E2.5 | No | ND | |||

| Pak-20 | DV3 | LLC-MK2 | 1E2.1 | No | ND | |||

| H-241 | DV4 | Mice | 1E6.6e | No | ND | |||

| Saguinus oedipus | in | NGC | DV1 | Mice | 1E5.3e | Yes | + | |

| H87 | DV3 | Mice | 1E6.2e | Yes | ND | |||

| Pak-20 | DV3 | LLC-MK2 | 1E2.7 | No | ND | |||

| H241 | DV4 | Mice | 1E5.6e | No | ND | |||

| Aotus trivirgatus | in | Hawaii | DV1 | Mice | 1E5.7e | No | ND | |

| NGC | DV2 | Mice | 1E6.6e | Yes | ND | |||

| Pak-20 | DV3 | LLC-MK2 | 1E2.1 | Yes | ND | (Scherer et al., 1972) | ||

| Macaca mulatta (Indian) | sc | 16007 | DV1 | LLC-MK2 | 5E5 | Yes | 1.7E3 | Lymphadenopathy in DV1, 2, & 4, rare hemorrhaging in DV1& 4, leucopenia |

| 16681 | DV2 | LLC-MK2 | 5E5 | Yes | 4.8E2 | In DV2 & 4, lymphocytosis was common | ||

| 16562 | DV3 | LLC-MK2 | 5E5 | Yes | + | Thrombocytopenia in 21–33% of animals with all serotypes | ||

| 4328S | DV4 | LLC-MK2 | 5E5 | Yes | 2.8E2 | Complement decreases in secondary DV2, no change in behavior, eating or prothrombin | ||

| Macaca | sc, id | 16007 | DV1 | LLC-MK2 | NI | Yes | − | No disease |

| fascicularis | 16681 | DV2 | NI | Yes | − | |||

| fascicularis* | 16562 | DV3 | NI | Yes | − | |||

| 4328S | DV4 | NI | Yes | − | ||||

| Chlorocebus | sc, id | 16007 | DV1 | LLC-MK2 | 1E5 | Yes | + | No disease |

| aethiops* | 16681 | DV2 | 1E5 | Yes | + | |||

| 16562 | DV3 | 1E4.5 | Yes | + | ||||

| Erythrocebus | sc, id | 16007 | DV1 | LLC-MK2 | NI | Yes | + | No disease |

| patas | 16681 | DV2 | 1E5 | Yes | + | |||

| 16562 | DV3 | 1E4.5 | Yes | − | ||||

| 4328S | DV4 | 1E3.3 | Yes | − | (Halstead et al., 1973a,b) | |||

| Macaca mulatta | sc | 16007 | DV1 | LLC-MK2 | 1.2E5 | Yes | 350 | Lymphadenopathy, virus distribution after sc injection indicated that most virus did not move far from the inoculation site, day after viremia virus was distributed widely throughout skin (Marchette et al., 1973) |

| 16681 | DV2 | 2E6 | Yes | 443 | ||||

| 16562 | DV3 | 1E5 | Yes | 40 | ||||

| 4328S | DV4 | 1E6 | Yes | 1085 | ||||

| Pan troglodytes | id, sc | 49313 | DV1 | Mosquitoes | 1E3.1 | Yes | 1E6.6g | Nasal discharges and lymphadenopathy |

| NC38 | DV2 | Humans | 1E3.6 | Yes | 1E5.6g | Symptoms found in individual animals | ||

| 49080 | DV3 | Mosquitoes | 1E2.7 | Yes | 1E5.2g | Splenomegaly, leucopenia | ||

| 17111 | DV4 | Mosquitoes | 1E2.8 | Yes | 1E6g | Hemorrhage, shaking chill, lethargy (Scherer et al., 1978) | ||

| Macaca mulatta | sc | 16681 | DV2 | LLC-MK2 | 1E5 | Yes | 1E5.7 | Cyclophosphamide treatment caused chronic infection, 3/9 died, internal hemorrhaging, enlarged kidney, severe acute proliferative glomerulonephritis, pleural effusion, passively transferred antibody aided viral clearance (Marchette et al., 1980) |

| Macaca mulatta | sc | PR-159 | DV2 | FRhL | 5.6 | Yes | ND | No disease |

| H-241 | DV4 | 1.44 | (Kraiselburd et al., 1985) | |||||

| Macaca mulatta & Macaca fascicularis | is, im, it | 16007 | DV1 | PDK | 2.5E5 | Yes | ND | Mild neurovirulence (Angsubhakorn et al., 1987) |

| Aotus nancymae | sc | Western Pacific 74 | DV1 | NI | 2E4 | Yes | + | Pathology more pronounced in DV1, mild leucopenia, changes in attitude and appetite |

| S16803 | DV2 | Changes in fecal consistency, 2/20 became lethargic | ||||||

| CH53489 | DV3 | Common symptoms: lymphadenopathy, nasal discharges and splenomegaly (Schiavetta et al., 2003) | ||||||

| 341750 | DV4 | |||||||

| Aotus | sc | IQT6152 | DV1 | NI | 1E4 | Yes | + | No disease |

| nancymae | IQT2124 | DV2 | − | |||||

| OBS8041 | DV2 | + | (Kochel et al., 2005) | |||||

| Macaca | sc | 60305 | DV1 | Vero | 1E5 | Yes | 1E1.6 | No disease |

| mulatta | 16007 | DV1 | Vero | 1E5 | Yes | 1E2.4 | ||

| 16007 | DV1 | C6/36 | 1E5 | Yes | 1E1.9 | |||

| 40247 | DV2 | C6/36 | 1E5 | Yes | 1E3.6 | |||

| 44/2 | DV2 | Vero | 1E5 | Yes | 1E2.9 | |||

| H87 | DV3 | Vero | 1E5 | Yes | 1E2.7 | |||

| 16562 | DV3 | Vero | 1E5 | No | − | |||

| 74886 | DV3 | C6/36 | 1E5f | Yes | 1E2.2 | (Freire et al., 2007) | ||

| Macaca fascicularis | sc | 40514 | DV1 | NI | 1E6.4f | Yes | 400f | No disease, characterized T-cell and neut antibody cross-reactivity, no changes in |

| 28128 | DV4 | 1E6.2f | 20f | IFN-γ, TNFα, IL4, IL8, IL10 transcription during infection (Koraka et al., 2007) | ||||

| Macaca mulatta | sc | Western Pacific 74 | DV1 | NI | 1E4 | Yes | ND | No disease, increases in AST, transcriptional upregulation of |

| ISGs, OASs, Mxs, etc., no increases in cytokine gene expression (Sariol et al., 2007) | ||||||||

| Chlorocebus aethiops sabaeus | sc | SB8553 | DV2 | NI | 1E6 | Yes | + | No fever or lymphomegaly, no changes in behavior or weight, no respiratory, digestive or nervous system disturbances, lower inoculum titers gave prolonged viremia and better neut antibody responses (Martin et al., 2009) |

| Macaca mulatta (Indian) | iv | 16681 | DV2 | Vero | 1E7 | Yes | ~8E3 | Consistent hemorrhaging in 9/9 animals, decline in platelet count and leucopenia, elevated thrombin-antithrombin, D-dimers, ALT, and CK, no increases in hematocrit, prothrombin or activated PTT (Onlamoon et al., 2010) |

| Callithrix jacchus | sc | 02–17/1 | DV1 | C6/36 | 3.5E7 | Yes | 5E5h | No disease |

| DHF0663 | DV2 | 6.7E7 | 1.6E7h | Found differing NK, NKT, and niave effector memory and central T-cell kinetics during DV infection with different strains | ||||

| DSS1403 | DV3 | 4.5E6 | 5.5E4h | |||||

| 05-40/1 | DV4 | 1.5E6 | 2.5E4h | |||||

| Jam/77/07 | DV2 | 1.2E5 | 2.8E6h | |||||

| Mal/77/08 | DV2 | 1.9E5 | 9.6E6h | (Omatsu et al., 2011; Yoshida et al., 2013) | ||||

| Homo sapiens | sc | 45AZ5 | DV1 | FRhL | 2E3 | Yes | + | CD8+T-cell-dervied IFN-γ associated with protection from fever and viremia, sIL-R2α correlated with disease onset and severity, PBMC-derived TNF-α, IL-2, 4, 5, 10 did not correlate with protection or disease (Gunther et al., 2011; Sun et al., 2013) |

| CH53489 | DV3 | FRhL | 1E5 | |||||

| Macaca nemestrina | sc | 98900645 | DV3 | C6/36 | 1E7-1E8 | Yes | 62.94 | Inoculation route influenced virus-tissue distribution |

| id | 47.98 | Minimal hepatitis | ||||||

| iv | 58.62 | (Pamungkas et al., 2011) | ||||||

| Saguinus midas and Saguinus labiatus | sc | DHF0663 | DV2 | C6/36 | 6.7E7 | Yes | 2.7E6h | No disease, CD16+ NK cell depletion did not alter virus replication or pathogenesis |

| iv | 2E7h | (Yoshida et al., 2012) | ||||||

| Macaca mulatta (Indian) | sc | NGC | DV2 | NI | 1E5 | Yes | 257 | Day 14 PI showed the highest levels in T-cell activation, Anti-NS1, 3, & 5 T-cell responses were characterized (Mladinich et al., 2012) |

| Macaca mulatta (Chinese) | iv, sc | 16681 | DV2 | Vero | 1E7 | Yes | + | Hemorrhaging in 50% of iv inoculated primates (unpublished) |

Cell type or organism in which DV stock was propagated;

Highest inoculum dose is given when there were variable doses;

Titers given when available;

HID;

MLD50orMLD50/ml;

TCID50orTCID50/ml;

MID50/ml;

RNA/ml; +/−, indicates presence or absence of viremia, ic, intracardial; mi, mosquito inoculation; iv, intravenous; sc, subcutaneous; id, intradermal, ip, intraperitoneal; in, intranasal; im, intramuscular; is, intraspinal; it, intrathalmic; NI, not indicated; ND, not determined; MID50, mosquito infectious dose 50; TCID50, tissue culture infectious dose 50; MLD50, suckling mouse intracranial lethal dose 50; HID, human minimal infectious dose;

indicatesspeciesnamechange.

The most consistent pathological finding in these animals have been lymphadenopathy of the inguinal and auxiliary lymph nodes (Halstead et al., 1973a; Marchette et al., 1973; Scherer et al., 1978; Schiavetta et al., 2003). In one species, Chlorocebus aethiops sabaeus, the absence of lymphomegaly (Martin et al., 2009) and in a few reports, splenomegaly (a rare symptom in humans) were noted (Scherer et al., 1978; Schiavetta et al., 2003). Fever is a valid parameter to assess, but its recording in DV-infected primates is logistically difficult, and is therefore rarely reported (Scherer et al., 1972). NHPs in general have higher body temperatures and greater variability than human bodies (Scherer et al., 1972; Fuller et al., 1985), so unless readings are measured on awake animals by telemetry, the anesthesia used profoundly alters the body's temperature, making accurate readings impossible (Baker et al., 1976). Another human dengue symptom, cutaneous rashes, are not commonly observed in primates but may be underreported; also tourniquet tests are never performed on primates to assess capillary fragility. Behavioral changes, like lethargy, have been documented in only a few studies (Chandler and Rice, 1923; Scherer et al., 1978; Schiavetta et al., 2003). In general, primates kept and bred in captivity rarely display overt disease.

Despite the low incidence of pathology observed in these studies, dengue infections in primates share many characteristics with human disease. The onset and duration of viremia is similar to humans, or about 3–6 days starting from the second day after inoculation (Freire et al., 2007; Koraka et al., 2007). Leucopenia has been observed (Onlamoon et al., 2010). Thrombocytopenia has never been captured in NHPs, likely because of their naturally high platelet counts, but moderate platelet decreases have been document in M. mulatta (Halstead et al., 1973a; Onlamoon et al., 2010). A DV-induced reduction of dengue-specific antibodies during the early phases of secondary homologous infection, a phenomenon observed in viremic patients, has been seen in marmosets (Omatsu et al., 2011). The anti-dengue antibodies that are elicited in primates are highly cross-reactive against other closely related flaviviruses (Scherer et al., 1978). DV infection of monkeys elicits a vigorous innate response (Sariol et al., 2007) leading to activation and marked shifts in circulating subsets of T, NK, and NK-T cells in the marmoset model (Yoshida et al., 2013). The role of DV specific cell-mediated responses in NHP models has received relatively less attention, although some studies reported recognition of non-structural proteins in addition to viral components by both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Koraka et al., 2007; Mladinich et al., 2012). However, such responses have been difficult to detect in immunized monkeys, even in those that show protection from challenge (Chen et al., 2007; Porter et al., 2012).

The similarities observed in these studies imply that primates may present with more suitable symptoms than mouse models upon further manipulation. A comparison of the benefits to using the NHP and murine animal models is given (Table 2). Several strategies to improve the NHP model may be explored—for instance increasing the number of permissive cells or altering the immune environment. Here we discuss boosting viremia with different virus delivery strategies.

Table 2.

Relative advantages in using primate and murine model systems to study DV disease.

| Primate models | Murine models | |

|---|---|---|

| Ease of use/cost | − | + |

| Susceptibility to human DV strains | + | − |

| Mimic human viremia | (+) reduced | + |

| Mimic human immune responses | + | − |

| MODEL HUMAN DISEASE | ||

| Fever | − | CD34-engrafted humanized mouse |

| Hemorrhages | Indian rhesus monkey | CD34-engrafted humanized mouse, C57BL/6 |

| Platelet count reduction | Indian rhesus monkey | CD34-engrafted humanized mouse |

| Hepatomegaly | − | Balb/c |

| Pleural effusion | − | − |

| CNS disease* | − | + |

| DHF/DSS | − | − |

| Lethality | − | + |

+, commonly present; −, absent;

Rarely observed in human dengue infections.

Virus delivery

Only a limited number of studies have attempted determining the infectious dose delivered during natural dengue infection. One study suggests the amount of DV transmitted by A. aegypti ranges from 1 × 104 to 1 × 105 (Gubler and Rosen, 1976). However, there are disagreements over the best methods to conduct such studies; the controversial points include mosquito species, generation number, feeding strategy, infection method, incubation temperature and length, virus strain and technique used to quantify transmitted virus. All these variables have the potential to affect the infection dynamics and alter the conclusions of the study (Chamberlain et al., 1954; Grimstad et al., 1980; Mellink, 1982; Watts et al., 1987; Colton et al., 2005; Smith et al., 2005). Some studies have suggested levels as high as 1 × 108.7 genome equivalents or almost 1 × 107 PFUs can be transmitted, though rarely (Colton et al., 2005; Styer et al., 2007). Currently we know as few as 1000 PFUs can cause viremia and disease symptoms in humans (Sun et al., 2013). Ultimately the natural inoculum dose is more suggestive of the amount of virus needed for continual DV transmission in vivo and does not necessarily reflect the quantity required for disease induction. Viremia levels and disease may be less dependent on inoculum size and more contingent on host-pathogen interactions. These matters should be considered when modeling DV infection in animals.

Virus delivery to the proper tissues is important for inducing the appropriate interactions with the host and promoting disease presentation. DV deposition is believed to occur exclusively by direct inoculation into the subcutaneous layer by mosquitoes. However, the subcutaneous infection route does not promote adequate virus dissemination (Marchette et al., 1973; Pamungkas et al., 2011). Potentially the virus is restricted by less frequent encounters with migrating cells and immobilization by attachment to extracellular matrix proteins (Anez et al., 2009). Consider that mosquito feeding involves the probing of all layers of skin, including the cutaneous layer and capillaries, to find a blood meal. These tissues are an integral part of the arbovirus-vector lifecycle and are frequently evaluated in transmission studies (Chamberlain et al., 1954; Styer et al., 2007). Virus injected directly into these tissues have better access to and faster dissemination throughout the body, affording the virus more opportunities to rapidly reach distant target cells (Pamungkas et al., 2011). Additionally, pathology induction is likely promoted by rapid viral dissemination and replication in distant cells and organs. This assumption led us to hypothesize that an intravenous infection strategy would favor wide dissemination and allow for rapid simultaneous replication of virus in various tissues, invoking a more pronounced innate immune response, potentially reflective of the human immune environment during high viremia. Although the kinetics of viremia did not markedly differ between subcutaneous and intravenous DV2 infection (Onlamoon et al., 2010; Omatsu et al., 2011), it will be critical to delineate the overall kinetics of DV dissemination to and replication in various tissues and how this relates to the induction of symptoms.

Rhesus macaque model of coagulopathy

Only a few NHP dengue investigations have reported rashes post-infection (PI) (Lavinder and Francis, 1914; Halstead et al., 1973b; Onlamoon et al., 2010). In most of these studies, hemorrhaging was a rare event. However, our group reported a reproducible coagulopathy disease model in the Indian rhesus macaque when 9 out of 9 monkeys inoculated intravenously with 1 × 107 PFUs of DV2 (16681) displayed evidence of subcutaneous hemorrhage (Onlamoon et al., 2010). The viremia noted in these animals remained at the high end of the range typically reported in other NHP studies and were reached relatively consistently at early time points PI.

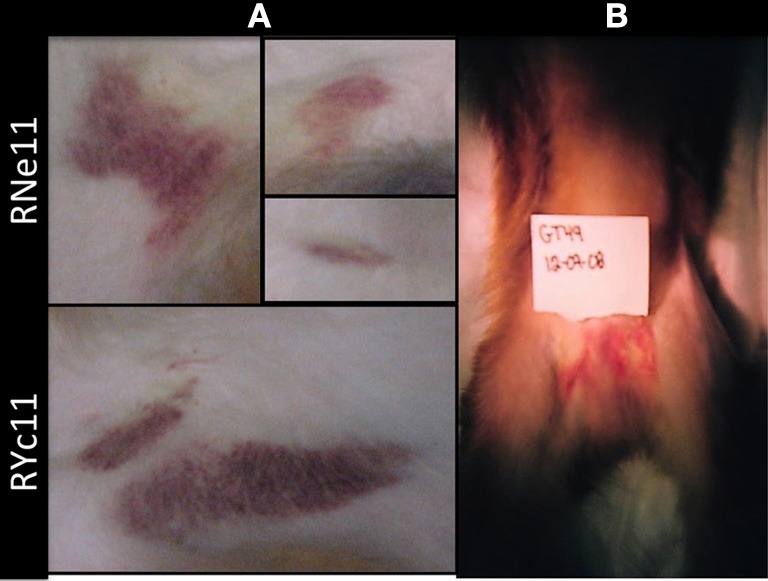

The most prominent symptoms observed in our studies with the Indian rhesus macaque were cutaneous hemorrhages, starting at Days 3 and 4 PI and lasting as long as 10 days (Figure 1A) (Onlamoon et al., 2010). In a pilot study using Chinese rhesus macaques, disease presentation with the same virus was more modest, suggesting that these NHPs may be less susceptible to disease. Large hematomas developed in only one of the two primates infected intravenously with DV2 (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Hematomas are seen in intravenously inoculated rhesus macaques. (A) Indian rhesus macaques were injected intravenously with 1 × 107 PFUs of DV2 16681 as previously reported (Onlamoon et al., 2010). Hematomas of various degrees of severity were present on Days 3 till 14 PI. Prominent ecchymoses were visible in two young male animals, RNell and RYc11, on Day 7. (B) Four Chinese rhesus macaques were injected intravenously (n = 2) or subcutaneously (n = 2) with 1 × 107 PFUs of DV2 16681 strain. Hemorrhaging was only observed in 1 of 2 IV-injected monkeys (GT49), depicted in the picture above on Day 6 PI. No hematomas were observed in subcutaneously inoculated macaques.

The dynamics of various leukocyte subsets were followed longitudinally PI. Similar to human dengue, these animals experienced the typical leucopenia or a modest but consistent decrease in white blood cells that reached a nadir at Day 7 PI, but returned to normal levels by Day 10 (Onlamoon et al., 2010). Platelets also modestly decreased until Day 3, corresponding to the time of peak DV RNA load (Noisakran et al., 2012). While these leukocyte values did not fall out-of-range for macaques the changes were clearly noticeable and consistent. There was also a modest decrease in hematocrit, which resolved with the clearance of viremia at Day 7, in spite of continuous blood and bone marrow (BM) draws (Onlamoon et al., 2010).

A longitudinal monitoring of coagulatory parameters hinted that a number of features may be important for hemorrhage formation (Onlamoon et al., 2010). Increased time to clotting was noted during blood collection of some Indian rhesus macaques, indicating an increased susceptibility toward bleeding. However, thromboplastin and prothrombin times did not indicate abnormal clotting. Protein C and anti-thrombin III levels did not vary from pre-inoculation values, but they were predominantly in the high end of the reference range. Marked elevations were noted for D-dimers, TAT complexes and protein S, with peaks most consistently present on Days 5–10 PI, corresponding to the resolution of viremia. This data requires further confirmation with additional time points, more animals spanning various ages and other DV isolates. However, we submit that we might for the first time have a model to investigate coagulopathy similar to DHF, which can allow for better evaluation of preventative and therapeutic strategies to prevent pathogenesis, not just infection.

Interestingly, analysis of serum chemistry parameters indicated relatively modest changes for all parameters except creatine phosphokinase (CK), which was markedly elevated on Day 7 (Onlamoon et al., 2010). CK is a component in energy metabolism (with multiple isoenzymatic forms: MM, MB, and BB) that are altered in individuals with a number of different illnesses (Roberts and Sobel, 1973; Saks et al., 1978). Heightened levels of CK have been noted in Crimean Congo and Influenza patients (Middleton et al., 1970; Ergonul et al., 2004). Additionally, a recent report confirms elevation of this enzyme in dengue patients and suggests it is linked to muscle weakness/dysfunction during malaise (Misra et al., 2011). However, CK is a non-specific biomarker that is elevated in various conditions, and thus its diagnostic value is limited. Since these enzymes are quite highly elevated during DV infection, there could be a meaningful relationship between CK and disease. CK and creatine phosphates in combination are known as ADP scavengers and participate in modulating platelet activities, such as aggregation (Chignard et al., 1979; Chesney et al., 1982; Krishnamurthi et al., 1984; Jennings, 2009), which may consequently modulate immune cell activation/function and by extension, pathogenesis (Wong et al., 2013).

Bone marrow (BM) targeting

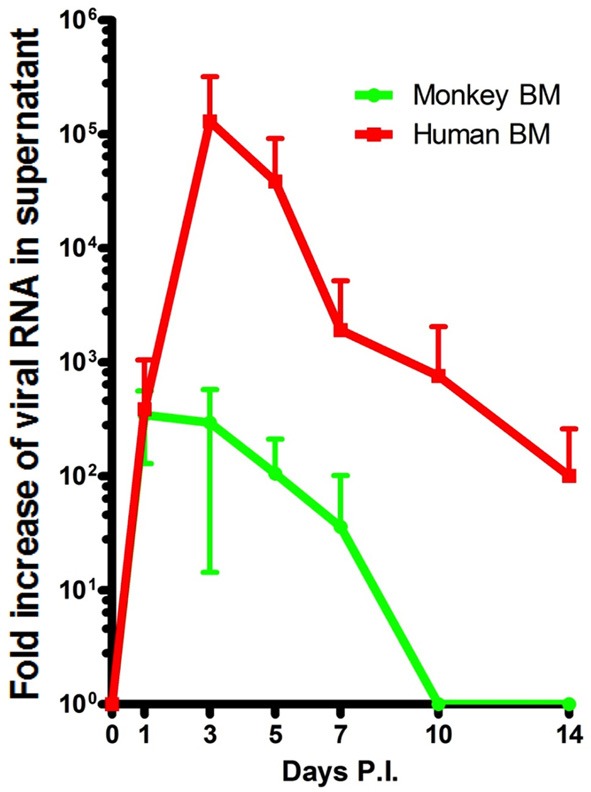

The BM can be involved in hemodynamic defects; alterations in the BM environment may result in altered leukocyte function and contribute to pathogenesis (Wilson and Trumpp, 2006; Duffy et al., 2012). DV has long been known to alter hematopoiesis in human BM (Bierman and Nelson, 1965; La Russa and Innis, 1995). However, collecting BM aspirates from DV patients is contraindicated. Additionally, infections in patients can be misleading due to the variability in disease onset and the uncertainty of sample time points. Experimentation in animal models in which the induction of infection is known allows for better analysis in real time. Our rhesus monkeys were sampled for BM repeatedly on a rotating basis resulting in the collection of at least 3 samples at each time point spanning Days 1–14 PI. This has allowed for us to confirm that BM cellularity is indeed depressed during early acute DV infection (Noisakran et al., 2012). Aspirates were also monitored for the presence of DV in attempts to identify the initial cellular reservoirs of infection. While the general consensus is that DV targets phagocytes, such acquisition could be secondary to amplification in other cell types. In vitro both human and monkey BMs are permissive for DV replication, and similar to in vivo, peak titers differ by 1000-fold (Figure 2) (Clark et al., 2012). Characteristics of the early host cells were also evaluated in our model both in vivo and in vitro (Clark et al., 2012; Noisakran et al., 2012). Of interest DV antigen was primarily detected in CD41+ CD61+ cells during the first 3 days, followed by a gradual shift toward CD14+ phagocytes at later time points, coinciding with viral clearance (Clark et al., 2012). The results suggest that megakaryocytes represent the initial target of DV in BM, rather than a member of the monocytic lineage. Direct infection of these cells may account for the altered megakaryocyte composition (Nelson et al., 1964), impaired platelet function (Srichaikul and Nimmannitya, 2000; Cheng et al., 2009) and the incidence of platelet phagocytosis observed in previous studies (Nelson et al., 1966; Honda et al., 2009; Onlamoon et al., 2010). Platelet activation and function during the course of infection has been under-investigated but may be critical for unraveling the mechanisms responsible for dengue pathology.

Figure 2.

Peak DV titers in rhesus macaque BMs is markedly lower than that of humans. BMs were acquired and infected as previously described (Clark et al., 2012). Samples from Days 1 through 14 were quantified by realtime PCR. Human (red) and monkey (green) titers are depicted in RNA copy numbers per ml. The in vitro experimentation of whole BM indicates that human BM is able to produce far more virus than monkey BM. Titers appear to max out on average closer to Day 1 in monkey BM but reach their peak (~1000-fold higher) on Day 3 PI in humans.

Platelet activities

The role of platelets in the crafting of the immune response is imperfectly defined and only recently becoming recognized (Klinger and Jelkmann, 2002; Ombrello et al., 2010). These anucleated cells are able to associate with and deliver signals to other lineages and shape immune responses. Abnormal platelet behavior during dengue infection may play a significant role in modifying lymphocyte, monocyte and granulocyte function. When platelet-leukocyte interactions were quantified in vivo, macrophages/monocytes appeared to be the most commonly associated cell lineage with platelets (Onlamoon et al., 2010), with a majority of these monocyte-platelet aggregates expressing activation marker CD62P (Onlamoon et al., 2010). This data is reminiscent of other reports linking activated monocytes to disease pathology in humans (Mustafa et al., 2001; Bozza et al., 2008; Durbin et al., 2008).

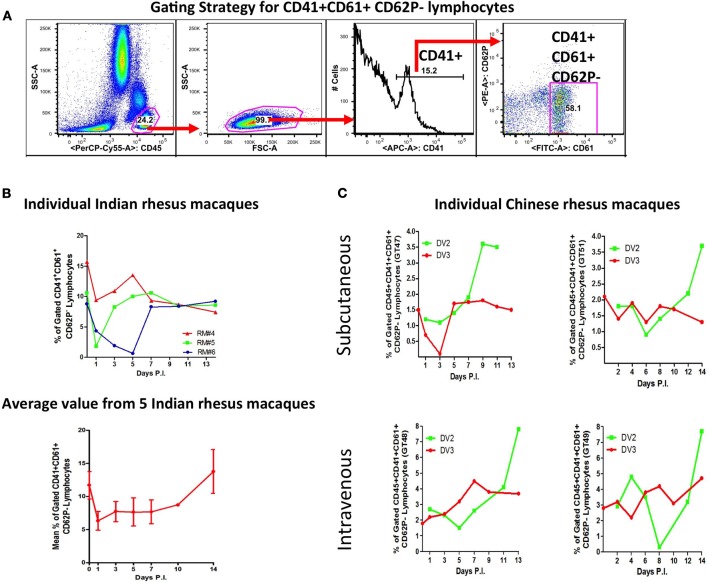

Platelets binding to neutrophils and lymphocytes were less frequent (Figures 3A–C) (Onlamoon et al., 2010). Only about 20–40% of neutrophils were bound with platelets, with 30–60% expressing CD62P. However, the extend of neutrophil-platelet aggregatation may be underestimated, since these cells are short-lived and other markers for neutrophil (CD11b and CD66b) and platelet (CD154, cleaved PAR1, CD63) activation were not tested (Heijnen et al., 1999; Claytor et al., 2003; Kinhult et al., 2003; Sprague et al., 2008). Lymphocyte-platelet aggregation occurred the least (Figures 3B,C). This was examined with Indian and Chinese rhesus macaques during primary DV2 (16681) infection and in Chinese macaques during secondary DV3 (Hawaii) infection (Figures 3B,C respectively). Since the dominant phenotype of the lymphocyte-platelet aggregate (LymPA) population was CD62P negative, this was the only population evaluated. Chinese and Indian macaques have different baseline levels of CD41+CD61+CD62P− lymphocytes, approximately 2% and 12%, respectively (Figures 3B,C). The average response from 5 Indian macaques suggests that the LymPA population is down-regulated (to about 7%) during infection but returns to normal levels after viral clearance (Figure 3B). In Chinese macaques, there appeared to be higher LymPA frequencies with the IV-inoculated monkeys, ranging up to 8% but only as high as 4% in SC-inoculated primates (Figure 3C). There was a late phase expansion of this population after primary but not after secondary infection. The functional significance of such changes is unclear at the present, but it would be interesting to compare these findings with other viral infections, like influenza, which produce robust long-lived B cell memory responses (Ikonen et al., 2010; Li et al., 2012). It remains to be seen whether this observation represents a common immune phenomenon or a DV specific response, which would potentially open a new line of investigation.

Figure 3.

Dynamics of lymphocyte-platelet aggregates (LymPA) during DV infection. Indian and Chinese rhesus macaques were infected as detailed in Figure 1. In addition, the Chinese macaques were challenged 2 months later with DV3 strain Hawaii. Peripheral blood samples obtained on Days 1 through 14 were subjected to flow cytometric analysis with CD45, CD41, CD61, and CD62P fluorescent antibodies. The frequencies of CD45+CD41+CD61+CD62P− cells over time is graphed. (A) Panels to illustrate the gating strategy employed to analyze lymphocyte-platelet aggregates (LymPA). (B) The kinetics of LymPA in Indian rhesus macaques. The top graph displays LymPA frequencies from 3 individual macaques and the bottom graph, the average population frequency from 5 primates. The LymPA population is down-regulated during DV infection in Indian rhesus macaques. (C) LymPA kinetics in subcutaneously and intravenously infected Chinese rhesus macaques during primary DV2 (green line) and secondary DV3 infection (red line). The frequency of LymPA increases late after primary but not after secondary infection.

Potential refinements to the coagulopathy monkey model

Virus selection

While the data obtained with our rhesus macaque model appears promising, many parameters remain to be examined and refined. Arguably, the most important factor to evaluate is different strains. The viruses we used had been propagated extensively in cell culture, and thus the next step will be to evaluate primary DV strains, which are considered more capable of inducing pathology. Interestingly, the earliest DV studies (pre-1940s) in primates were conducted with human-derived virus that had never been propagated through cell culture (Lavinder and Francis, 1914; Chandler and Rice, 1923; Blanc et al., 1929; Simmons et al., 1931), yet these investigations induced minimal overt disease. The human-derived Hawaiian and New Guinea strains from Sabin's work were pathogenic in humans (when inoculated intradermally) but demonstrated no pathology in Rosen's study when inoculated into various primate species via a subcutaneous or intraperitoneal route (Sabin, 1952; Rosen, 1958). In recent studies, a large number of the strains employed were recent clinical isolates minimally passaged in vitro (Freire et al., 2007; Omatsu et al., 2011; Pamungkas et al., 2011; Yoshida et al., 2012). While these viruses are often close in sequence to the original isolate, these strains are not necessarily the most virulent or capable of achieving the targeted pathology in primates (Omatsu et al., 2011) and may require further evaluation before use in vivo.

The major drawbacks of primate models are the logistics and cost. Ideally one would perform preliminary experiments and evaluate strain virulence through a screening tool before in vivo studies with NHPs. Virulence could be assessed by testing the induction of disease in the humanized mouse or potentially by growth characteristics in monkey whole BM. Alternatively, passage of dengue in organisms (humanized mice or rhesus macaques) may ensure that the strain is more fit for these studies. It has been suggested that mouse-passaged viruses are more capable at causing viremia in NHPs than in vitro-passaged strains (Scherer et al., 1972).

Considering the viruses that have already been tested in NHPs, a select few appear promising for future studies. WP-74 (DV1) and S16803 (DV2) caused extreme lethargy in owl monkeys (Schiavetta et al., 2003) but not in cynomolgus (Koraka et al., 2007) or rhesus macaques (Ajariyakhajorn et al., 2005; Robert Putnak et al., 2005). Besides the 16681 DV2 virus, strains 49313 (DV1), 16007 (DV1), and 43283 (DV4) were associated with hemorrhage in previous studies (Halstead et al., 1973b; Scherer et al., 1978). Testing these strains in our Indian macaque model could lead to a more frequent presentation of coagulopathy and models for 3 of the 4 dengue serotypes. For future preclinical vaccine and drug studies, one strain of each serotype that can induce easily quantifiable disease will be needed for better vaccine evaluation.

Other parameters

A number of additional parameters may be manipulated in rhesus macaques that could amplify disease severity. Factors from infected mosquito saliva may potentiate the virus in down-modulating immune responses during the initiation of infection and help raise peak titer levels (Cox et al., 2012; Reagan et al., 2012; Surasombatpattana et al., 2012; Le Coupanec et al., 2013). Mosquito inoculation of DV into NHPs was modeled long ago without inducing much disease (Simmons et al., 1931). However, a number of confounding factors (preexisting immunity, inoculum quality, etc.) were not accounted for in these studies, indicating that this approach is worth revisiting.

Modulation of in vivo cell populations with drug treatments has rarely been attempted (Marchette et al., 1980; Yoshida et al., 2012). Potential treatment of macaques with megakaryocytic growth factors, like thrombopoetin, could increase the number of early permissive targets and enhance peak viral load if indeed megakaryocytes are the primary replication site for DV (Nakorn et al., 2003). General immunosuppression has been attempted but led to chronic viremia, which does not mimic human DV disease (Marchette et al., 1980). Depletion of macrophages, neutrophils or other innate immune responders may enhance titers by altering the dynamics of viral clearance. One previous attempt at CD16+ natural killer cell depletion did not modulate virus titers (Yoshida et al., 2012), although such depletions are generally partial at best. Additionally, various inoculum sizes and alternative inoculation routes may be tested. The intradermal inoculation route was suggested to lead to better virus tissue distribution, but did not result in better dissemination to the BM (Pamungkas et al., 2011). Characterization of these parameters are necessary for the further refinement of the coagulopathy disease animal model.

Host characteristics or genetic factors that increase susceptibility to coagulopathy

Epidemiological studies of dengue patient characteristics, including age, sex and genetic polymorphisms have been frequently studied, but none of these findings have been validated in animal models (Loke et al., 2001; Stephens et al., 2002; Cordeiro et al., 2007; Kalayanarooj et al., 2007; Soundravally and Hoti, 2007; Stephens, 2010). In humans, the age of greatest susceptibility to disease is seen in young adults (Tsai et al., 2012). In our Indian rhesus macaques, we have evaluated age as a contributing factor to viremia by comparing the titers of DV when propagated in whole BM in vitro (unpublished data). However, no difference was noted in virus growth kinetics or magnitude related to age of BM donors (n = 11), which spanned 2–15 years of age. In vivo, anecdotal observations suggested that coagulopathy appeared to be more extensive in older female macaques when compared to young males, which were the populations included in the study, although sample size was too low to be conclusive. This nevertheless raises an interesting question about the potential for host factors contributing to the severity of symptoms.

Various MHC alleles, blood group and platelet antigens have been found to be associated with dengue disease and protection (Kalayanarooj et al., 2007; Soundravally and Hoti, 2007; Alagarasu et al., 2013; Weiskopf et al., 2013). Although in general these associations are weak as biomarkers of disease. One of our goals is to assess gene alleles involved with regulating platelet activation and the coagulatory cascade e.g., HPA1, HPA2 for association with disease presentation. Available techniques, such as Macaca mulatta typing and gene expression analyses, will need to be an integral part of future experiments with the rhesus monkey model to facilitate identification of genetic factors involved with dengue-induced abnormal coagulation.

Conclusion

The induction of disease symptoms upon the inoculation of DV in primates has been an elusive objective. Recently a coagulopathy disease model was developed using the serotype 2 strain 16681 injected intravenously into Indian rhesus macaques. We submit that this approach provides a strategy for detailed investigation of the mechanisms potentially involved in DHF. Moreover, the model provides an attractive algorithm for testing the efficacy of preventative vaccines and therapeutics that not only limit virus replication but also prevent disease development in vivo. Various host and viral parameters can begin to be evaluated in vivo to help us gain a better understanding of dengue biology and disease pathogenesis. Can pathology be induced in other NHPs by switching to the intravenous route? Will different virus strains promote coagulopathy, or other symptoms? Can we alter other parameters and achieve a more severe disease model? The establishment of this new rhesus macaque infection model has proved insightful on ways to improve disease presentation in primates.

Human subject and animal research

Use of deidentified human BM was provided by Emory Hospital and approved by the Emory University Internal Review Board. Investigations with rhesus macaques were approved by Yerkes and Tulane IACUCs and conducted at either the Yerkes or Tulane National Primate Research Centers. Research was performed in accordance with institutional and national guidelines and regulations.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Thanks should be given to the staffs of Yerkes and Tulane National Primate Research Centers for the handling of monkeys and facilitating these investigations. Dr. John Roback aided with acquiring human BM samples to perform in vitro assays. Funding was acquired from U19 Pilot Project Funds (RFA-AI-02-042), National Institutes of Health/SERCEB, Emory URC grant, and P510D11123 in support to the Yerkes National Primate Research Center.

References

- Ajariyakhajorn C., Mammen M. P., Jr., Endy T. P., Gettayacamin M., Nisalak A., Nimmannitiya S., et al. (2005). Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of nonpegylated and pegylated forms of recombinant human alpha interferon 2a for suppression of dengue virus viremia in rhesus monkeys. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother. 49, 4508–4514 10.1128/AAC.49.11.4508-4514.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akkina R. (2013). New generation humanized mice for virus research: comparative aspects and future prospects. Virology 435, 14–28 10.1016/j.virol.2012.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akkina R., Berges B. K., Palmer B. E., Remling L., Neff C. P., Kuruvilla J., et al. (2011). Humanized Rag1−/− gammac−/− mice support multilineage hematopoiesis and are susceptible to HIV-1 infection via systemic and vaginal routes. PLoS ONE 6:e20169 10.1371/journal.pone.0020169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alagarasu K., Mulay A. P., Singh R., Gavade V. B., Shah P. S., Cecilia D. (2013). Association of HLA-DRB1 and TNF genotypes with dengue hemorrhagic fever. Hum. Immunol. 74, 610–617 10.1016/j.humimm.2013.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anez G., Men R., Eckels K. H., Lai C. J. (2009). Passage of dengue virus type 4 vaccine candidates in fetal rhesus lung cells selects heparin-sensitive variants that result in loss of infectivity and immunogenicity in rhesus macaques. J. Virol. 83, 10384–10394 10.1128/JVI.01083-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angsubhakorn S., Moe J. B., Marchette N. J., Latendresse J. R., Palumbo N. E., Yoksan S., et al. (1987). Neurovirulence detection of dengue virus using rhesus and cynomolgus monkeys. J. Virol. Methods 18, 13–24 10.1016/0166-0934(87)90106-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avirutnan P., Punyadee N., Noisakran S., Komoltri C., Thiemmeca S., Auethavornanan K., et al. (2006). Vascular leakage in severe dengue virus infections: a potential role for the nonstructural viral protein NS1 and complement. J. Infect. Dis. 193, 1078–1088 10.1086/500949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker M. A., Cronin M. J., Mountjoy D. G. (1976). Variability of skin temperature in the waking monkey. Am. J. Physiol. 230, 449–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo L., Izquierdo A., Prado I., Rosario D., Alvarez M., Santana E., et al. (2008). Primary and secondary infections of Macaca fascicularis monkeys with Asian and American genotypes of dengue virus 2. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 15, 439–446 10.1128/CVI.00208-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierman H. R., Nelson E. R. (1965). Hematodepressive virus diseases of Thailand. Ann. Intern. Med. 62, 867–884 10.7326/0003-4819-62-5-867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc G., Caminopetros J., Dumas J., Saenz A. (1929). Recherches experimentales sur la sensibilite des singes inferieurs au virus de la dengue. Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des seances de l'academie des sciences T188, 468–470 [Google Scholar]

- Bozza F. A., Cruz O. G., Zagne S. M., Azeredo E. L., Nogueira R. M., Assis E. F., et al. (2008). Multiplex cytokine profile from dengue patients: MIP-1beta and IFN-gamma as predictive factors for severity. BMC Infect. Dis. 8:86 10.1186/1471-2334-8-86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain R. W., Kissling R. E., Sikes R. K. (1954). Studies on the North American arthropod-borne encephalitides. VII. Estimation of amount of eastern equine encephalitis virus inoculated by infected Aedes aegypti. Am. J. Hyg. 60, 286–291 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler A. S., Rice L. (1923). Observations on the etiology of dengue fever. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. s1–s3, 233–262 [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Ewing D., Subramanian H., Block K., Rayner J., Alterson K. D., et al. (2007). A heterologous DNA prime-Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus replicon particle boost dengue vaccine regimen affords complete protection from virus challenge in cynomolgus macaques. J. Virol. 81, 11634–11639 10.1128/JVI.00996-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H. J., Lei H. Y., Lin C. F., Luo Y. H., Wan S. W., Liu H. S., et al. (2009). Anti-dengue virus nonstructural protein 1 antibodies recognize protein disulfide isomerase on platelets and inhibit platelet aggregation. Mol. Immunol. 47, 398–406 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.08.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney C. M., Pifer D. D., Byers L. W., Muirhead E. E. (1982). Effect of platelet-activating factor (PAF) on human platelets. Blood 59, 582–585 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chignard M., Le Couedic J. P., Tence M., Vargaftig B. B., Benveniste J. (1979). The role of platelet-activating factor in platelet aggregation. Nature 279, 799–800 10.1038/279799a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark K. B., Noisakran S., Onlamoon N., Hsiao H. M., Roback J., Villinger F., et al. (2012). Multiploid CD61+ cells are the pre-dominant cell lineage infected during acute dengue virus infection in bone marrow. PLoS ONE 7:e52902 10.1371/journal.pone.0052902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claytor R. B., Michelson A. D., Li J. M., Frelinger A. L., 3rd., Rohrer M. J., Garnette C. S., et al. (2003). The cleaved peptide of PAR1 is a more potent stimulant of platelet-endothelial cell adhesion than is thrombin. J. Vasc. Surg. 37, 440–445 10.1067/mva.2003.129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobra C., Rigau-Perez J. G., Kuno G., Vorndam V. (1995). Symptoms of dengue fever in relation to host immunologic response and virus serotype, Puerto Rico, 1990–1991. Am. J. Epidemiol. 142, 1204–1211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colton L., Biggerstaff B. J., Johnson A., Nasci R. S. (2005). Quantification of West Nile virus in vector mosquito saliva. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 21, 49–53 10.2987/8756-971X(2005)21[49:QOWNVI]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro M. T., Silva A. M., Brito C. A., Nascimento E. J., Magalhaes M. C., Guimaraes G. F., et al. (2007). Characterization of a dengue patient cohort in Recife, Brazil. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 77, 1128–1134 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox H. R. (1953). Active immunization against poliomyelitis. Bull. N.Y. Acad. Med. 29, 943–960 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J., Mota J., Sukupolvi-Petty S., Diamond M. S., Rico-Hesse R. (2012). Mosquito bite delivery of dengue virus enhances immunogenicity and pathogenesis in humanized mice. J. Virol. 86, 7637–7649 10.1128/JVI.00534-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy D., Perrin H., Abadie V., Benhabiles N., Boissonnas A., Liard C., et al. (2012). Neutrophils transport antigen from the dermis to the bone marrow, initiating a source of memory CD8+ T cells. Immunity 37, 917–929 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbin A. P., Vargas M. J., Wanionek K., Hammond S. N., Gordon A., Rocha C., et al. (2008). Phenotyping of peripheral blood mononuclear cells during acute dengue illness demonstrates infection and increased activation of monocytes in severe cases compared to classic dengue fever. Virology 376, 429–435 10.1016/j.virol.2008.03.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endy T. P., Nisalak A., Chunsuttitwat S., Vaughn D. W., Green S., Ennis F. A., et al. (2004). Relationship of preexisting dengue virus (DV) neutralizing antibody levels to viremia and severity of disease in a prospective cohort study of DV infection in Thailand. J. Infect. Dis. 189, 990–1000 10.1086/382280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ergonul O., Celikbas A., Dokuzoguz B., Eren S., Baykam N., Esener H. (2004). Characteristics of patients with Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in a recent outbreak in Turkey and impact of oral ribavirin therapy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 39, 284–287 10.1086/422000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox A., Le N. M., Simmons C. P., Wolbers M., Wertheim H. F., Pham T. K., et al. (2011). Immunological and viral determinants of dengue severity in hospitalized adults in Ha Noi, Viet Nam. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 5:e967 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire M., Marchevsky R., Almeida L., Yamamura A., Caride E., Brindeiro P., et al. (2007). Wild dengue virus types 1, 2 and 3 viremia in rhesus monkeys. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 102, 203–208 10.1590/S0074-02762007005000011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller C. A., Sulzman F. M., Moore-Ede M. C. (1985). Role of heat loss and heat production in generation of the circadian temperature rhythm of the squirrel monkey. Physiol. Behav. 34, 543–546 10.1016/0031-9384(85)90046-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green S., Pichyangkul S., Vaughn D. W., Kalayanarooj S., Nimmannitya S., Nisalak A., et al. (1999). Early CD69 expression on peripheral blood lymphocytes from children with dengue hemorrhagic fever. J. Infect. Dis. 180, 1429–1435 10.1086/315072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimstad P. R., Ross Q. E., Craig G. B., Jr. (1980). Aedes triseriatus (Diptera: Culicidae) and La Crosse virus. II. Modification of mosquito feeding behavior by virus infection. J. Med. Entomol. 17, 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubler D. J., Rosen L. (1976). A simple technique for demonstrating transmission of dengue virus by mosquitoes without the use of vertebrate hosts. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 25, 146–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilarde A. O., Turchi M. D., Siqueira J. B., Jr., Feres V. C., Rocha B., Levi J. E., et al. (2008). Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever among adults: clinical outcomes related to viremia, serotypes, and antibody response. J. Infect. Dis. 197, 817–824 10.1086/528805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunther V. J., Putnak R., Eckels K. H., Mammen M. P., Scherer J. M., Lyons A., et al. (2011). A human challenge model for dengue infection reveals a possible protective role for sustained interferon gamma levels during the acute phase of illness. Vaccine 29, 3895–3904 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.03.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halstead S. B., Shotwell H., Casals J. (1973a). Studies on the pathogenesis of dengue infection in monkeys. I. Clinical laboratory responses to primary infection. J. Infect. Dis. 128, 7–14 10.1093/infdis/128.1.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halstead S. B., Shotwell H., Casals J. (1973b). Studies on the pathogenesis of dengue infection in monkeys. II. Clinical laboratory responses to heterologous infection. J. Infect. Dis. 128, 15–22 10.1093/infdis/128.1.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halstead S. B., Suaya J. A., Shepard D. S. (2007). The burden of dengue infection. Lancet 369, 1410–1411 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60645-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley K. A., Monath T. P., Weaver S. C., Rossi S. L., Richman R. L., Vasilakis N. (2013). Fever versus fever: the role of host and vector susceptibility and interspecific competition in shaping the current and future distributions of the sylvatic cycles of dengue virus and yellow fever virus. Infect. Genet. Evol. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heijnen H. F., Schiel A. E., Fijnheer R., Geuze H. J., Sixma J. J. (1999). Activated platelets release two types of membrane vesicles: microvesicles by surface shedding and exosomes derived from exocytosis of multivesicular bodies and alpha-granules. Blood 94, 3791–3799 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda S., Saito M., Dimaano E. M., Morales P. A., Alonzo M. T., Suarez L. A., et al. (2009). Increased phagocytosis of platelets from patients with secondary dengue virus infection by human macrophages. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 80, 841–845 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikonen N., Strengell M., Kinnunen L., Osterlund P., Pirhonen J., Broman M., et al. (2010). High frequency of cross-reacting antibodies against 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) virus among the elderly in Finland. Euro Surveill. 15, 1–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings L. K. (2009). Mechanisms of platelet activation: need for new strategies to protect against platelet-mediated atherothrombosis. Thromb. Haemost. 102, 248–257 10.1160/TH09-03-0192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalayanarooj S., Gibbons R. V., Vaughn D., Green S., Nisalak A., Jarman R. G., et al. (2007). Blood group AB is associated with increased risk for severe dengue disease in secondary infections. J. Infect. Dis. 195, 1014–1017 10.1086/512244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinhult J., Egesten A., Benson M., Uddman R., Cardell L. O. (2003). Increased expression of surface activation markers on neutrophils following migration into the nasal lumen. Clin. Exp. Allergy 33, 1141–1146 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2003.01682.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinger M. H., Jelkmann W. (2002). Role of blood platelets in infection and inflammation. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 22, 913–922 10.1089/10799900260286623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochel T. J., Watts D. M., Gozalo A. S., Ewing D. F., Porter K. R., Russell K. L. (2005). Cross-serotype neutralization of dengue virus in Aotus nancymae monkeys. J. Infect. Dis. 191, 1000–1004 10.1086/427511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koizumi T. K. Y., Tonomura K. (1917). The research of dengue disease. Taiwan Igakukai Zasshi 177, 432–463 [Google Scholar]

- Koraka P., Benton S., van Amerongen G., Stittelaar K. J., Osterhaus A. D. (2007). Characterization of humoral and cellular immune responses in cynomolgus macaques upon primary and subsequent heterologous infections with dengue viruses. Microbes Infect. 9, 940–946 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraiselburd E., Gubler D. J., Kessler M. J. (1985). Quantity of dengue virus required to infect rhesus monkeys. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 79, 248–251 10.1016/0035-9203(85)90348-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthi S., Westwick J., Kakkar V. V. (1984). Regulation of human platelet activation—analysis of cyclooxygenase and cyclic AMP-dependent pathways. Biochem. Pharmacol. 33, 3025–3035 10.1016/0006-2952(84)90604-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuruvilla J. G., Troyer R. M., Devi S., Akkina R. (2007). Dengue virus infection and immune response in humanized RAG2(−/−)gamma(c)(−/−) (RAG-hu) mice. Virology 369, 143–152 10.1016/j.virol.2007.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Russa V. F., Innis B. L. (1995). Mechanisms of dengue virus-induced bone marrow suppression. Baillieres Clin. Haematol. 8, 249–270 10.1016/S0950-3536(05)80240-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavinder C. H., Francis E. (1914). The Etiology of Dengue. An attempt to produce the disease in the rhesus monkey by the inoculation of defibrated blood. J. Infect. Dis. 15, 341–346 10.1093/infdis/15.2.341 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Le Coupanec A., Babin D., Fiette L., Jouvion G., Ave P., Misse D., et al. (2013). Aedes mosquito saliva modulates Rift Valley fever virus pathogenicity. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 7:e2237 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei H. Y., Yeh T. M., Liu H. S., Lin Y. S., Chen S. H., Liu C. C. (2001). Immunopathogenesis of dengue virus infection. J. Biomed. Sci. 8, 377–388 10.1007/BF02255946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G. M., Chiu C., Wrammert J., McCausland M., Andrews S. F., Zheng N. Y., et al. (2012). Pandemic H1N1 influenza vaccine induces a recall response in humans that favors broadly cross-reactive memory B cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 9047–9052 10.1073/pnas.1118979109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libraty D. H., Acosta L. P., Tallo V., Segubre-Mercado E., Bautista A., Potts J. A., et al. (2009). A prospective nested case-control study of Dengue in infants: rethinking and refining the antibody-dependent enhancement dengue hemorrhagic fever model. PLoS Med. 6:e1000171 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libraty D. H., Young P. R., Pickering D., Endy T. P., Kalayanarooj S., Green S., et al. (2002). High circulating levels of the dengue virus nonstructural protein NS1 early in dengue illness correlate with the development of dengue hemorrhagic fever. J. Infect. Dis. 186, 1165–1168 10.1086/343813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y. L., Liao C. L., Chen L. K., Yeh C. T., Liu C. I., Ma S. H., et al. (1998). Study of Dengue virus infection in SCID mice engrafted with human K562 cells. J. Virol. 72, 9729–9737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loke H., Bethell D. B., Phuong C. X., Dung M., Schneider J., White N. J., et al. (2001). Strong HLA class I—restricted T cell responses in dengue hemorrhagic fever: a double-edged sword? J. Infect. Dis. 184, 1369–1373 10.1086/324320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch S. L. C. (2007). Plasma microparticles and vascular disorders. Br. J. Haematol. 137, 36–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mairuhu A. T., Mac Gillavry M. R., Setiati T. E., Soemantri A., Ten Cate H., Brandjes D. P., et al. (2003). Is clinical outcome of dengue-virus infections influenced by coagulation and fibrinolysis? A critical review of the evidence. Lancet Infect. Dis. 3, 33–41 10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00487-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchette N. J., Halstead S. B., Falkler W. A., Jr., Stenhouse A., Nash D. (1973). Studies on the pathogenesis of dengue infection in monkeys. 3. Sequential distribution of virus in primary and heterologous infections. J. Infect. Dis. 128, 23–30 10.1093/infdis/128.1.23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchette N. J., O'Rourke T., Halstead S. B. (1980). Studies on dengue 2 virus infection in cyclophosphamide-treated rhesus monkeys. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 168, 35–47 10.1007/BF02121650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markoff L. J., Innis B. L., Houghten R., Henchal L. S. (1991). Development of cross-reactive antibodies to plasminogen during the immune response to dengue virus infection. J. Infect. Dis. 164, 294–301 10.1093/infdis/164.2.294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J., Hermida L., Castro J., Lazo L., Martinez R., Gil L., et al. (2009). Viremia and antibody response in green monkeys (Chlorocebus aethiops sabaeus) infected with dengue virus type 2: a potential model for vaccine testing. Microbiol. Immunol. 53, 216–223 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2009.00112.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellink J. J. (1982). Estimation of the amount of Venezuelan equine encephalomyelitis virus transmitted by a single infected Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae). J. Med. Entomol. 19, 275–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer E., Heyman Z., Bin H., Schwartz E. (2012). Capillary leakage in travelers with dengue infection: implications for pathogenesis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 86, 536–539 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.10-0670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton P. J., Alexander R. M., Szymanski M. T. (1970). Severe myositis during recovery from influenza. Lancet 2, 533–535 10.1016/S0140-6736(70)91343-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra U. K., Kalita J., Maurya P. K., Kumar P., Shankar S. K., Mahadevan A. (2011). Dengue-associated transient muscle dysfunction: clinical, electromyography and histopathological changes. Infection 40, 125–130 10.1007/s15010-011-0203-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mladinich K. M., Piaskowski S. M., Rudersdorf R., Eernisse C. M., Weisgrau K. L., Martins M. A., et al. (2012). Dengue virus-specific CD4(+) and CD8(+) T lymphocytes target NS1, NS3 and NS5 in infected Indian rhesus macaques. Immunogenetics 64, 111–121 10.1007/s00251-011-0566-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mota J., Rico-Hesse R. (2011). Dengue virus tropism in humanized mice recapitulates human dengue fever. PLoS ONE 6:e20762 10.1371/journal.pone.0020762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murgue B., Deparis X., Chungue E., Cassar O., Roche C. (1999). Dengue: an evaluation of dengue severity in French Polynesia based on an analysis of 403 laboratory-confirmed cases. Trop. Med. Int. Health 4, 765–773 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1999.00478.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murgue B., Roche C., Chungue E., Deparis X. (2000). Prospective study of the duration and magnitude of viraemia in children hospitalised during the 1996-1997 dengue-2 outbreak in French Polynesia. J. Med. Virol. 60, 432–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa A. S., Elbishbishi E. A., Agarwal R., Chaturvedi U. C. (2001). Elevated levels of interleukin-13 and IL-18 in patients with dengue hemorrhagic fever. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 30, 229–233 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2001.tb01575.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakorn T. N., Miyamoto T., Weissman I. L. (2003). Characterization of mouse clonogenic megakaryocyte progenitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 205–210 10.1073/pnas.262655099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson E. R., Bierman H. R., Chulajata R. (1964). Hematologic Findings in the 1960 Hemorrhagic Fever Epidemic (Dengue) in Thailand. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 13, 642–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson E. R., Bierman H. R., Chulajata R. (1966). Hematologic phagocytosis in postmortem bone marrows of dengue hemorrhagic fever. (Hematologic phagocytosis in Thai hemorrhagic fever). Am. J. Med. Sci. 252, 68–74 10.1097/00000441-196607000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noisakran S., Onlamoon N., Hsiao H. M., Clark K. B., Villinger F., Ansari A. A., Perng G. C. (2012). Infection of bone marrow cells by dengue virus in vivo. Exp. Hematol. 40, 250–259 e254. 10.1016/j.exphem.2011.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussenblatt R. B., Bielekova B., Childs R., Krensky A., Strober W., Trinchieri G. (2010). National Institutes of Health Center for Human Immunology Conference. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. E1–E23 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05682.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oishi K., Inoue S., Cinco M. T., Dimaano E. M., Alera M. T., Alfon J. A., et al. (2003). Correlation between increased platelet-associated IgG and thrombocytopenia in secondary dengue virus infections. J. Med. Virol. 71, 259–264 10.1002/jmv.10478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omatsu T., Moi M. L., Hirayama T., Takasaki T., Nakamura S., Tajima S., et al. (2011). Common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) as a primate model of dengue virus infection: development of high levels of viraemia and demonstration of protective immunity. J. Gen. Virol. 92, 2272–2280 10.1099/vir.0.031229-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ombrello C., Block R. C., Morrell C. N. (2010). Our expanding view of platelet functions and its clinical implications. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 3, 538–546 10.1007/s12265-010-9213-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onlamoon N., Noisakran S., Hsiao H. M., Duncan A., Villinger F., Ansari A. A., et al. (2010). Dengue virus-induced hemorrhage in a nonhuman primate model. Blood 115, 1823–1834 10.1182/blood-2009-09-242990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pamungkas J., Iskandriati D., Saepuloh U., Affandi M., Arifin E., Paramastri Y., et al. (2011). Dissemination in pigtailed macaques after primary infection of dengue-3 virus. Microbiol. Indones. 5, 94–98 10.5454/mi.5.2.7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paul J. R., Melnick J. L., Sabin A. B. (1948). Experimental attempts to transmit phlebotomus (sandfly, pappataci) and dengue fevers to chimpanzees. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 68, 193–198 10.3181/00379727-68-16431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perng G. C., Chokephaibulkit K. (2013). Immunologic hypo- or non-responder in natural dengue virus infection. J. Biomed. Sci. 20:34 10.1186/1423-0127-20-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter K. R., Ewing D., Chen L., Wu S. J., Hayes C. G., Ferrari M., et al. (2012). Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of a vaxfectin-adjuvanted tetravalent dengue DNA vaccine. Vaccine 30, 336–341 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.10.085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnak R., Barvir D. A., Burrous J. M., Dubois D. R., D'Andrea V. M., Hoke C. H., et al. (1996). Development of a purified, inactivated, dengue-2 virus vaccine prototype in Vero cells: immunogenicity and protection in mice and rhesus monkeys. J. Infect. Dis. 174, 1176–1184 10.1093/infdis/174.6.1176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raviprakash K., Porter K. R., Kochel R. J., Ewing D., Simmons M., Phillips I., et al. (2000). Dengue virus type 1 DNA vaccine induces protective immune responses in rhesus macaques. J. Gen. Virol. 81, 1659–1667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reagan K. L., Machain-Williams C., Wang T., Blair C. D. (2012). Immunization of mice with recombinant mosquito salivary protein D7 enhances mortality from subsequent West Nile virus infection via mosquito bite. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 6:e1935 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert Putnak J., Coller B. A., Voss G., Vaughn D. W., Clements D., Peters I., et al. (2005). An evaluation of dengue type-2 inactivated, recombinant subunit, and live-attenuated vaccine candidates in the rhesus macaque model. Vaccine 23, 4442–4452 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.03.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts R., Sobel B. E. (1973). Ediortial: Isoenzymes of creatine phosphokinase and diagnosis of myocardial infarction. Ann. Intern. Med. 79, 741–743 10.7326/0003-4819-79-5-741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen L. (1958). Experimental infection of New World monkeys with dengue and yellow fever viruses. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 7, 406–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabin A. B. (1952). Research on dengue during World War II. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1, 30–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabin A. B., Schlesinger R. W. (1945). Production of immunity to dengue with virus modified by propagation in mice. Science 101, 640–642 10.1126/science.101.2634.640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito M., Oishi K., Inoue S., Dimaano E. M., Alera M. T., Robles A. M., et al. (2004). Association of increased platelet-associated immunoglobulins with thrombocytopenia and the severity of disease in secondary dengue virus infections. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 138, 299–303 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02626.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saks V. A., Rosenshtraukh L. V., Smirnov V. N., Chazov E. I. (1978). Role of creatine phosphokinase in cellular function and metabolism. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 56, 691–706 10.1139/y78-113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]