Abstract

The group of 21 novel semi-synthetic derivatives of quercetin was screened for the antiradical efficiency in a DPPH assay. The initial fast absorbance decrease of DPPH, corresponding to the transfer of the most labile H atoms, was followed by a much slower absorbance decline representing the residual antiradical activity of the antioxidant degradation products. Initial velocity of DPPH decolorization determined for the first 75-s interval was used as a marker of the antiradical activity. Application of the kinetic parameter allowed good discrimination between the polyphenolic compounds studied. The most efficient chloronaphthoquinone derivative (compound Ia) was characterized by antiradical activity higher than that of quercetin and comparable with that of trolox. Under the experimental conditions used, one molecule of Ia was found to quench 2.6±0.1 DPPH radicals.

Keywords: antioxidant, quercetin derivatives, DPPH assay, kinetics, stoichiometry

Introduction

The antioxidant action of flavonoids, the best described biological activity of this group of natural polyphenolic substances, is covered by a number of excellent reviews (Bors et al., 1990; Cao et al., 1997; Pietta, 2000; Rice-Evans, 2001; Nijveldt et al., 2001; Bors & Michel, 2002; Heim et al., 2002; Williams et al., 2004; Amič et al., 2007; Bischoff, 2008; Boots et al., 2008). Flavonoids exert antioxidant effects by different mechanisms as e.g. free radical scavenging, hydrogen donating, singlet oxygen quenching, and metal iron chelating. Within the flavonoid family, quercetin (Qc) is the most potent scavenger of reactive oxygen species, including superoxide, peroxyl, alkoxyl and hydroxyl radicals, and reactive nitrogen species like NO· and ONOO· (Pietta, 2000; Butkovič et al., 2004; Amič et al., 2007; Boots et al., 2008). Flavonoids were found also to scavenge efficiently the model free radicals of 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) (Butkovič et al., 2004).

Quercetin O-glycosides, represent one of the most ubiquitous structures of all plant phenolics (Materska 2008). In addition, synthetic acyl derivatives of Qc, including aliphatic acids such as acetic, malonic and 2-hydroxypropionic acid, or aromatic acids, including benzoic, gallic, caffeic and ferulic acid, are frequently used as synthetic alternative to natural glycoside moieties (Harborne ed., 1994). Acylated Qc derivatives constitute useful active principles for cosmetic, dermatopharmaceutical, pharmaceutical or dietetic compositions (Perrier et al., 2001; Golding et al., 2001). The glycosidic structure has a large impact on quercetin bioavailability (Arts et al. 2004; Crozier et al. 2010, Stefek and Karasu 2011). The biological activity of Qc derivatives, including their antioxidant action, strongly depends on the nature and position of the substituents. It is important to modify selectively the various hydroxyls, which are not equivalent from either the chemical or biofunctional point of view. The general structural requirements for effective radical scavenging and/or the antioxidant potential of flavonoids are summarized in Bors’ criteria (Bors & Michel, 2002; Amič et al., 2007).

In the present paper, 21 novel semi-synthetic derivatives of Qc were screened for antiradical efficiency in a DPPH assay in comparison with the parent Qc and the standard antioxidant trolox. Stoichiometry of the DPPH quenching reaction was determined for the most efficient derivative.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

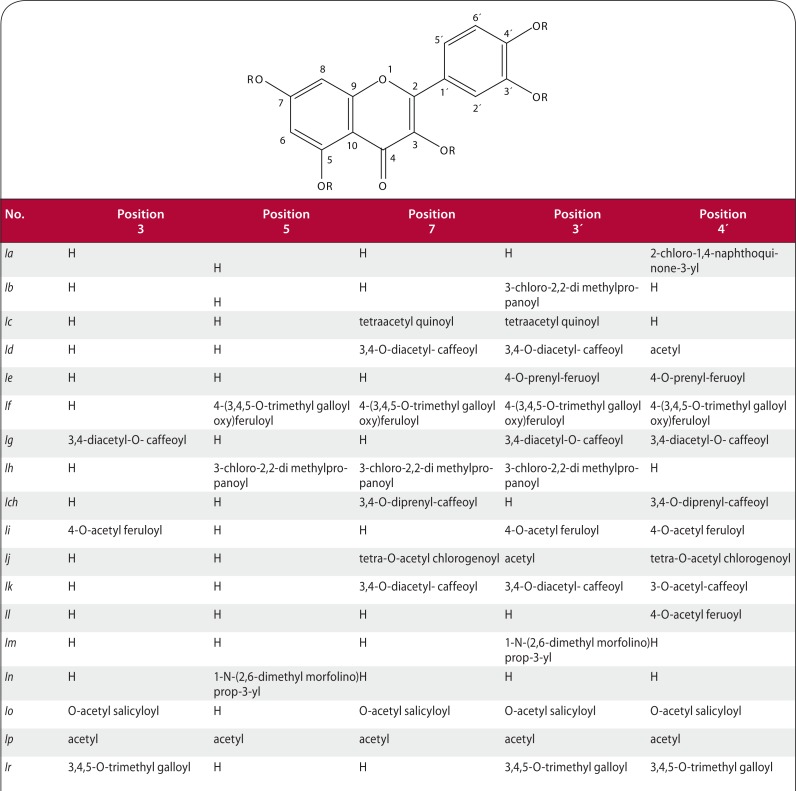

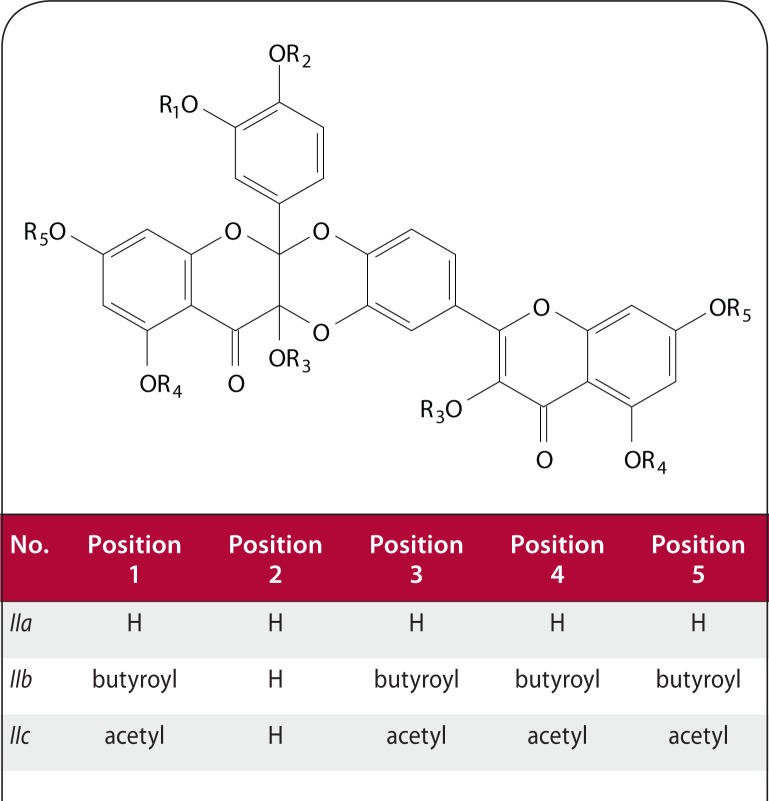

Samples of new semi-synthetic derivatives of Qc Ia–Ir (Figure 1) were synthesized by reaction of appropriate acyl chloride with Qc or the corresponding protected derivative and then purified by repeated column chromatography of the rich reaction mixture. Qc was oxidized to generate heterodimer IIa (Figure 2). Diquercetin was treated with an anhydride to yield corresponding acyl derivatives IIb–IIc (Figure 2; Veverka et al. 2013).

Figure 1.

Compounds Ia–Ir.

Figure 2.

Compounds IIa–IIc.

1,1‘-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical was obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Other chemicals were purchased from local commercial sources and were of analytical grade quality.

DPPH test

To investigate the antiradical activity of the compounds studied, the ethanolic solution of DPPH (50 µM) was incubated in the presence of the given compound tested (50 µM) at laboratory temperature. The absorbance decrease, recorded at λmax = 518 nm, during the first 75-s interval was taken as a marker of the antiradical activity. During the 75-s interval used, an approximately linear decrease of DPPH absorbance was observed, which was considered as a good assessment of the initial velocity of the radical reaction.

The stoichiometry of the radical reaction was determined by spectrophotometric titration of the ethanolic solution of DPPH (50 µM) by increasing concentrations of an antioxidant with the reaction time long enough for completion of the reaction as indicated.

The radical studies were performed at the laboratory temperature.

Results and discussion

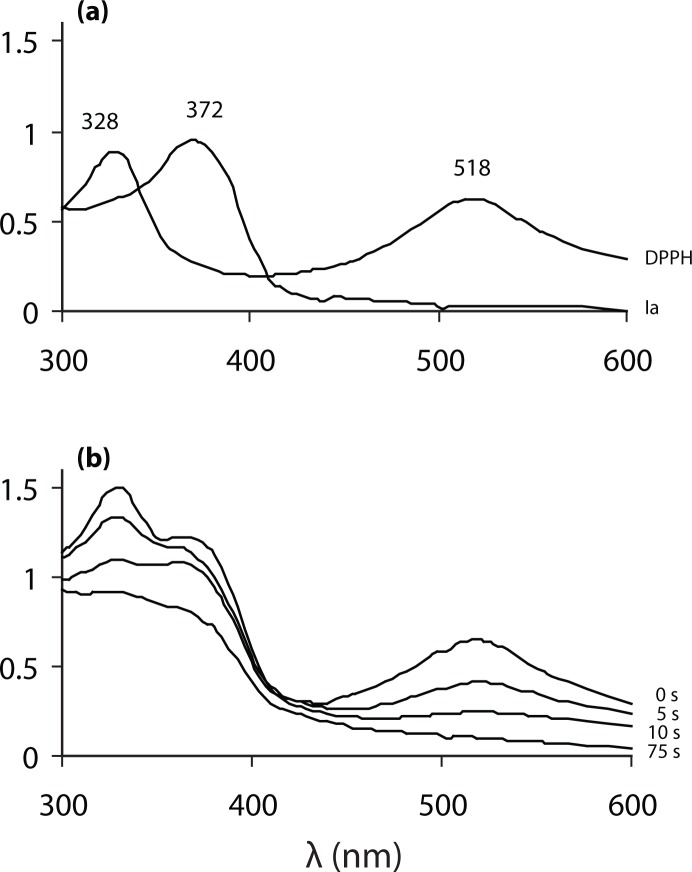

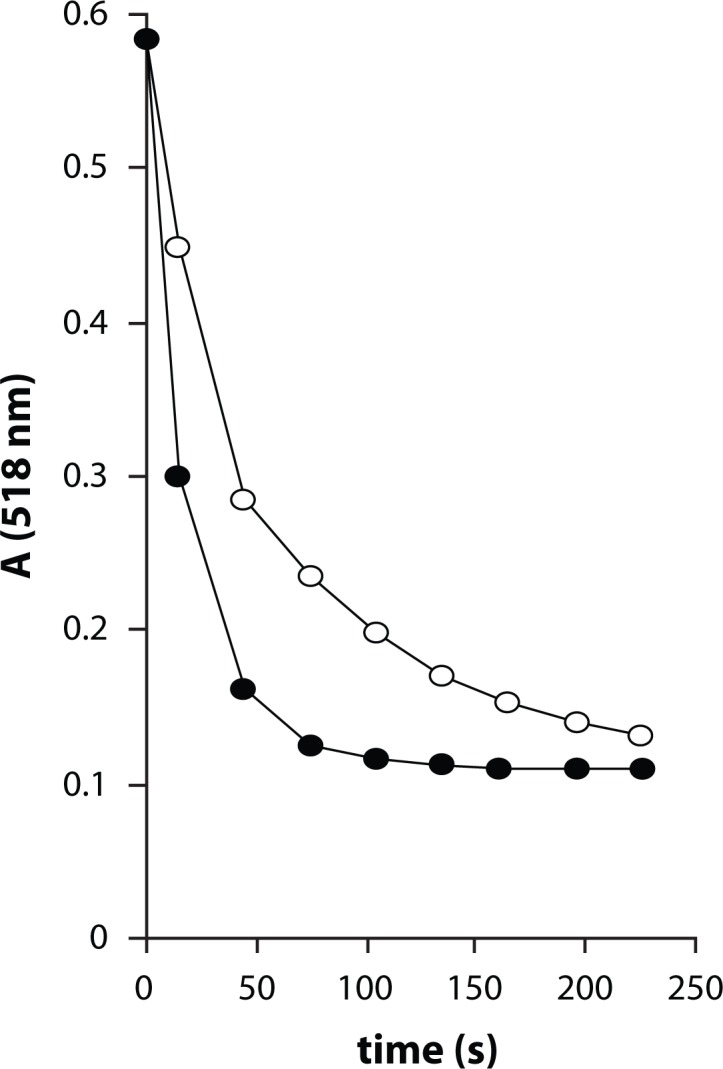

As a weak hydrogen atom abstractor, DPPH is considered a good kinetic model for peroxyl ROO· radicals (Blois, 1958; Ratty et al., 1988). DPPH assay is routinely used as a primary screening test of antiradical efficacy. Figure 3 shows UV-VIS spectra of DPPH and compound Ia with characteristic absorbance maxima and their time-dependent changes during the first 75 sec after mixing the reactants. The time-dependent decrease of the characteristic absorbance of the ethanolic solution of DPPH at 518 nm in the presence of Qc and one of its derivatives, Ia, is illustrated by Figure 4. As shown in Figure 4, the initial fast absorbance decrease, corresponding to the transfer of the most labile H atoms, is followed by a much slower absorbance decline representing the residual antiradical activity of the antioxidant degradation products. The initial velocity of DPPH decolorization determined for the first 75-s interval was used as a marker of antiradical activity. Based on the kinetic parameter the compounds studied were arranged according to their decreasing activity in comparison with the parent Qc and standard trolox, as shown in Table 1. It is apparent that a group of six new derivatives (Ia–Ie, IIa) exert antioxidant activity comparable with that of Qc and even slightly higher. The antiradical efficacy of the most efficient chloronaphthoquinone derivative Ia was found comparable with that of the standard trolox. The results indicate that application of the initial velocity of DPPH decolorization allows good discrimination between the polyphenolic compounds studied. In addition, the kinetic parameter is considered to be of primary importance in antioxidant evaluation since fast reaction with low concentrations of short-living damaging radicals is of utmost importance for antioxidant protection. Other authors applied the kinetic approach to rank flavonoids according to their antioxidant efficacy (Goupy et al. 2003; Butkovic et al. 2004; Villano et al. 2007).

Figure 3.

(a). UV-VIS spectra of DPPH (50 µM) and compound Ia (50 µM) with characteristic absorbance maxima; (b). Time dependent spectral changes in the mixture of DPPH (50 µM) and compound Ia (50 µM).

Figure 4.

Continual absorbance decrease of ethanolic solution of DPPH radical (50 µmol/l) in the presence of equimolar concentration of tested compounds at λmax = 518 nm.

(○)- Qc, (●) - chloronaphthoquinone derivative Ia. The curves represent results from two typical experiments.

Table 1.

Antiradical activities of novel quercetin derivatives, in comparison with parent quercetin and trolox standard, in a DPPH testa.

| Compound | MW | Absorbance decrease (-ΔA/75 s) |

|---|---|---|

| Ia Chloronaphthoquinone Qc | 492.82 | 0.462 ± 0.015 |

| Ib Monochloropivaloyl Qc | 420.80 | 0.446 ± 0.024 |

| Ic Ditetraacquinoyl Qc | 986.85 | 0.414 ± 0.021 |

| Id Acetyldidiacetcaffeoyl Qc | 836.72 | 0.391 ± 0.028 |

| Quercetin | 302.24 | 0.386 ± 0.025 |

| IIa Diquercetin | 602.46 | 0.374 ± 0.030 |

| Ie Di(prenylferuloyl)Qc | 790.82 | 0.316 ± 0.017 |

| If Tetratrimetylgaloxyferuloyl Qc | 1783.68 | 0.195 ± 0.011 |

| Ig Triacetylcaffeoyl Qc | 1040.9 | 0.121 ± 0.012 |

| Ih Trichlorpivaloyl Qc | 657.92 | 0.119 ± 0.030 |

| Ich Didiizoprenocaffeoyl Qc | 899.00 | 0.115 ± 0.031 |

| Ii Tri-acetylferuloyl Qc | 956.85 | 0.091 ± 0.012 |

| Ij Acetylchlorogenoyl Qc | 1437.25 | 0.063 ± 0.005 |

| Ik Triacetylcaffeoyl Qc | 998.86 | 0.043 ± 0.007 |

| Il Monoacetylferuloyl Qc | 520.45 | 0.040 ± 0.026 |

| Im 3′-Morfolinohydroxypropoxy Qc | 743.84 | 0.035 ± 0.021 |

| IIb Heptabutyroyl biQc | 1093.08 | 0.033 ± 0.012 |

| In 5-Morfolinohydroxypropoxy Qc | 473.47 | 0.014 ± 0.009 |

| Io Tetra acetylsalicyloyl Qc | 950.8 | 0.013 ± 0.003 |

| Ip Pentaacetyl Qc | 512.42 | 0.010 ± 0.009 |

| Ir Trimethylgaloyl Qc | 884.79 | 0.008 ± 0.004 |

| IIc Hepta/hexaacetyldi Qc 1:1 | 896.71/854.68 | 0.007 ± 0.006 |

| Trolox | - | 0.520 ± 0.025 |

The ethanolic solution of DPPH radical (50 µM) was incubated in the presence of the compound tested (50 µM). Absorbance decrease at 518 nm during the first 75-s interval was determined. Results are mean values ± SD from at least three measurements.

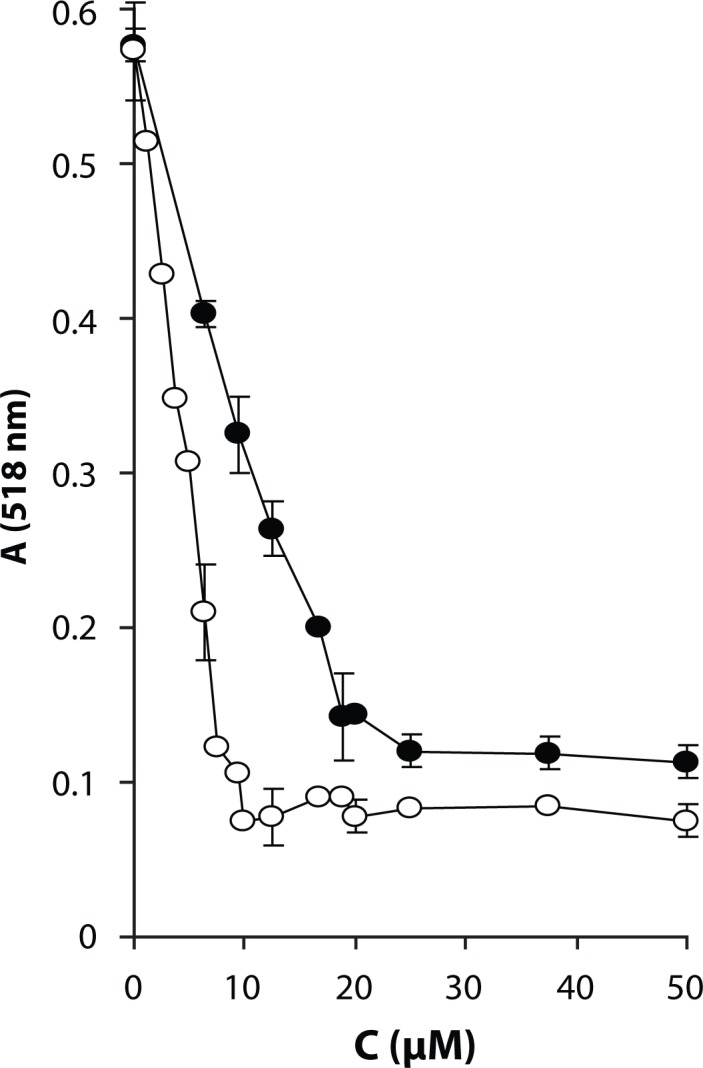

In general, the antioxidant efficacy is characterized not only by kinetics of free radical quenching but also by stoichiometry of the scavenging reaction. So for the most efficient chloronaphthoquinone derivative Ia, the total stoichiometry of DPPH scavenging was determined in comparison with the parent Qc. The technique of spectrophotometric titration of fixed concentration of DPPH (50 µmol/l) with increasing concentrations of the antioxidant was used to determine the point of equivalence. In this approach the reaction time was set long enough to let the reaction run to completion. Fig. 5 shows the absorbance decrease of the ethanolic solution of DPPH radical in the presence of increasing concentrations of the compounds tested. By analyzing the titration curves, points of equivalence were determined and corresponding stoichiometric factors were calculated. Under the experimental conditions used, one molecule of Ia was found to quench 2.6±0.1 DPPH radicals, while one molecule of Qc scavenged 5.5±0.2 DPPH radicals. The high stoichiometric ratio found for Qc is in agreement with findings of other authors (Goupy et al. 2003; Villano et al. 2007; Markovic et al. 2012) and indicates high antiradical activity of its decomposition products which is in contrast to compound Ia. To conclude, by using a DPPH assay, 21 novel derivatives of Qc were ranked according to their antiradical efficacy in comparison with the parent Qc and the standard trolox. For the most efficient derivative, stoichiometry of DPPH scavenging was determined.

Figure 5.

Stoichiometry of DPPH scavenging by the chloronaphthoquinone derivative of Qc Ia in comparison with Qc. Concentration dependence of absorbance decrease of ethanolic solution of DPPH radical (50 µmol/l) in the presence of increasing concentrations of the compounds tested at λmax = 518 nm.

(○) – Qc, time of reaction 1 h (●) – Ia, time of reaction 1.5 h. Results are mean values from two measurements or mean values±SD from three experiments.

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by The Agency of the Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic for the Structural Funds of EU, OP R&D of ERDF by realization of the Project “Evaluation of natural substances and their selection for prevention and treatment of lifestyle diseases” (ITMS 26240220040).

REFERENCES

- 1.Amić D, Davidović-Amić D, Beslo D, Rastija V, Lucić B, Trinajstić N. SAR and QSAR of the antioxidant activity of flavonoids. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:827–845. doi: 10.2174/092986707780090954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arts IC, Sesink AL, Faassen-Peters M, Hollman PC. The type of sugar moiety is a major determinant of the small intestinal uptake and subsequent biliary excretion of dietary quercetin glycosides. Br J Nutr. 2004;91:841–847. doi: 10.1079/BJN20041123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bischoff SC. Quercetin: potentials in the prevention and therapy of disease. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2008;11:733–740. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32831394b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blois MS. Antioxidant determinations by the use of a stable free radical. Nature. 1958;181:1199–1200. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boots AW, Haenen GRMM, Bast A. Health effects of quercetin: From antioxidant to nutraceutical. Eur J Pharm. 2008;585:325–337. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bors W, Heller W, Michel C, Saran M. Flavonoids as antioxidants. Determination of Radical-Scavanging Efficiences. In: Packer L, Glazer AN, editors. Methods in Enzymology. Vol. 186. San Diego CA: Academic Press; 1990. pp. 343–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bors W, Michel C. Chemistry of the Antioxidant. Effect of Polyphenols. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2002;957:57–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb02905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butkovic V, Klasinc L, Bors W. Kinetic Study of Flavonoid Reactions with Stable Radicals. J Agric Food Chem. 2004;52:2816–2820. doi: 10.1021/jf049880h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cao G, Sofic E, Prior RL. Antioxidant and prooxidant behavior of flavonoids: structure-activity relationships. Free Rad Biol Med. 1997;22:749–760. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(96)00351-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crozier A, Del Rio D, Clifford MN. Bioavailability of dietary flavonoids and phenolic compounds. Mol Aspects Med. 2010;31:446–467. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golding TB, Griffin JR, Quaterman PC, Slack AJ, Williams GJ. Analogues or derivatives of quercetin (prodrug); Washington, D.C.: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office; 2001. U.S. Patent Application No. 6258840 B1. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goupy P, Dufour C, Loonis M, Dangles O. Quantitative kinetic analysis of hydrogen transfer reactions from dietary polyphenols to the DPPH radical. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51(3):615–622. doi: 10.1021/jf025938l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harborne JB, editor. London: Chapman & Hall; 1995. The Flavonoids, Advances in Research Since 1986; pp. 378–382. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heim KE, Tagliaferro TR, Bobilya DJ. Flavonoid antioxidants: chemistry, metabolism and structure-activity relationships. J Nutr Biochem. 2002;13:572–584. doi: 10.1016/s0955-2863(02)00208-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dimitrić Marković JM, Marković ZS, Pašti IA, Brdarić TP, Popović-Bijelić A, Mojović M. A joint application of spectroscopic, electrochemical and theoretical approaches in evaluation of the radical scavenging activity of 3-OH flavones and their iron complexes towards different radical species. Dalton Trans. 2012;41(24):7295–7303. doi: 10.1039/c2dt30220a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Materska M. Quercetin and its derivatives: chemical structure and bioactivity-Rewiev. Pol J Food Nutr Sci. 2008;58:407–413. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nijveldt RJ, van Nood E, van Hoorn DEC, Boelens PG, van Norren K, van Leeuwen PAM. Flavonoids: a review of probable mechanisms of action and potential applications. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74:418. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.4.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perrier E, Mariotte AM, Boumendje A, Bresson-Rival D. Flavonoid esters and their use notably in cosmetics; Washington, D.C.: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office; 2001. U.S. Patent Application No. 6235294 B1. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pietta PG. Flavonoids as Antioxidants. J Nat Prod. 2000;63:1035. doi: 10.1021/np9904509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ratty AK, Sunammoto J, Das NP. Interaction of flavonoids with 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl free radical, liposomal membranes and soybean lipoxygenase-1. Biochem Pharmacol. 1988;37:989–996. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(88)90499-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rice-Evans C. Flavonoid Antioxidants. Curr Med Chem. 2001;8:797. doi: 10.2174/0929867013373011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stefek M, Karasu C. Eye lens in aging and diabetes: effect of quercetin. Rejuvenation Res. 2011;14(5):525–534. doi: 10.1089/rej.2011.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Veverka M, Gallovič J, Švajdlenka E, Veverková E, Pronayová N, Miláčková I, Štefek M. Novel quercetin derivatives: synthesis and screening for antioxidant activity and aldose reductase inhibition. Chem Papers. 2013;67(1):76–83. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Villaño D, Fernández-Pachón MS, Moyá ML, Troncoso AM, García-Parrilla MC. Radical scavenging ability of polyphenolic compounds towards DPPH free radical. Talanta. 2007;71(1):230–235. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2006.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams RJ, Spencer JP, Rice-Evans C. Flavonoids: antioxidants or signalling molecules? Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;36:838–849. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]