Abstract

Natural killer cells are the dominant population of immune cells in the endometrium in the secretory phase of the menstrual cycle and in the decidua in early pregnancy. The possibility that this is a site of NK cell development is of particular interest because of the cyclical death and regeneration of the NK population over the menstrual cycle. To investigate this, we searched for NK developmental stages 1 - 4, based on expression of CD34, CD117 and CD94. Here we report that a heterogeneous population of stage 3 NK precursor (CD34−CD117+CD94−) and mature stage 4 NK (CD34−CD117−/+CD94+) cells, but not multipotent stages 1 and 2 (CD34+), are present in the uterine mucosa. Cells within the uterine stage 3 population are able to give rise to mature stage 4-like cells in vitro but also produce IL-22 and express RORC and LTA. We also found stage 3 cells with NK progenitor potential in peripheral blood. We propose that stage 3 cells are recruited from the blood to the uterus, and mature in the uterine microenvironment to become distinctive uterine NK cells. IL-22 producers in this population might have a physiological role in this specialist mucosa dedicated to reproduction.

Introduction

Natural killer (NK) cells are large granular lymphocytes that kill infected or malignant cells and produce cytokines which regulate the immune response. NK cells are part of the innate immune system but share a common lineage with T and B lymphocytes, originating in humans from CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). The pathways and locations of NK cell development are currently less well defined than those of T and B cells, in part due to the heterogeneity of NK cell subsets and the diverse anatomical locations in which mature NK cells reside [1]. In particular, distinctive uterine NK cells (uNK) are present in the uterine mucosa and are abundant in the secretory phase of the non-pregnant menstrual cycle and the first trimester of pregnancy.

Although NK cells develop in multiple sites in adult mice, the essential role of bone marrow has long been known [2,3]. A complete pathway of NK development has been described in adult mouse bone marrow and the thymus is also a site of NK development [4, 5]. The situation in humans is less clear: CD34+ cells can be isolated from human bone marrow and induced to become CD56+ cytotoxic NK cells [6, 7], but a complete pathway of NK differentiation at this site has not been defined. The most complete scheme described in adult humans occurs in the secondary lymphoid tissue (SLT) [8]. A circulating NK progenitor cell, CD34+CD45RA+integrinβ7bright, accounts for approximately 6% of blood CD34+ cells but for more than 95% of SLT CD34+ cells [9]. Furthermore, SLT contains 4 stages of NK cell development, defined by CD34, CD117 (c-kit) and CD94 expression (Figure 1a) and every stage can be isolated and induced to differentiate into subsequent stages in vitro [8]. Therefore, the SLT hosts a complete pathway of NK cell development, starting with multipotential stage 1 (CD34+CD117−CD94−) and 2 (CD34+CD117+CD94−) cells, going through NK-committed stage 3 cells (CD34−CD117+CD94−) and finally becoming mature stage 4 (CD34−CD117+/−CD94+) NK cells. More recently it has emerged that SLT stage 3 is a heterogenous population, both phenotypically and functionally, in which some cells are more capable of acquiring markers of mature NK cells, while others produce IL-22 [10,11,12]. Blood CD56brightCD16− NK cells are equivalent to stage 4 and, since CD56bright cells can differentiate to CD56dim cells in vitro, blood CD56dimCD16+ NK cells may represent stage 5 [8,13].

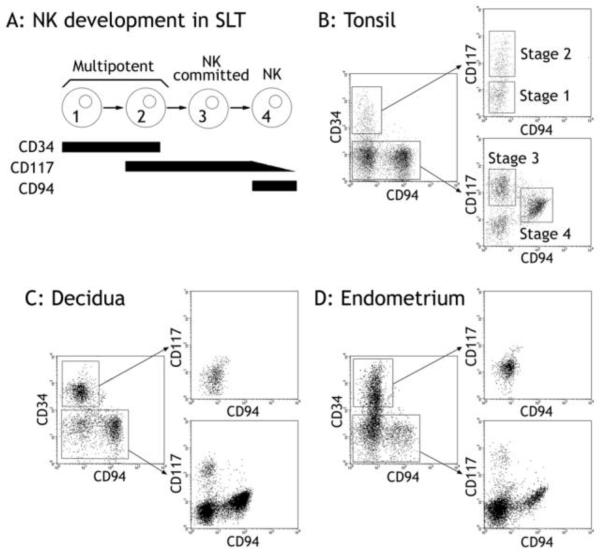

Figure 1. The uterine mucosa contains committed NK cell precursors.

A: Stages 1 – 4 of NK development in SLT [8]. B: Tonsillar leukocytes were mechanically dissociated and magnetically depleted for CD3+ and CD19+ cells. The remaining cells were stained with CD34, CD117 and CD94 and examined by flow cytometry. Cells were gated on scatter, and then on CD34+CD94− or on CD34− cells. Stages 1 - 4 are highlighted. Plots are representative of at least three independent samples. C and D: Decidual and endometrial leukocytes were obtained by collagenase digestion and depleted of stromal cells by a two-hour incubation on plastic. The non-adherent cells were then magnetically enriched for CD34+ cells, stained with CD34, CD117 and CD94 and examined by flow cytometry. Cells were gated by scatter and then on CD34+CD94− or on CD34− cells, demonstrating a single population of CD34+ cells, a population of CD117+CD94− corresponding to stage 3, and a CD94+ population corresponding to stage 4. CD117 and CD94 staining on CD34-enriched and non-enriched cells was similar (Supplementary Figure 1). Each panel is representative of at least three independent samples.

Large numbers of NK cells with a characteristic phenotype are present in the uterine mucosa and their functions may include regulation of trophoblast invasion and vascular remodelling [14,15]. NK cells in the blood are either CD56dimCD16+ or CD56brightCD16− [16] but uNK cells are CD56superbrightCD16−, have cytolytic granules and constitutively express Killer Immunoglobulin-like Receptors (KIR) [17-19]. The non-pregnant uterine mucosa (endometrium) undergoes cyclical shedding and regeneration during the menstrual cycle but if fertilization occurs it is transformed into decidua. Uterine NK cells are intimately involved in this cycle: they die en masse as progesterone levels fall pre-menstrually and are shed with the menses but reappear in the next menstrual cycle, proliferating after ovulation as progesterone levels rise [20]. If pregnancy occurs they persist until mid-gestation, accumulating in large numbers at the site of implantation and accounting for approximately 70% of all mucosal leukocytes. This remarkable cyclical regeneration of the NK population raises the question of their origin: can NK cell development occur in the uterine mucosa?

No consensus has yet been reached about whether human uNK cells develop from a resident HSC [21-23] or are recruited by uterine chemokines from circulating bone-marrow derived cells in adult life [23-27]. In mice, there is also evidence to support both of these possibilities [28-31]. To investigate whether NK cell differentiation might occur in the uterine mucosa, we searched for NK development stages 1 – 4. Our rationale for doing this was that CD34+CD45+ cells have been found in both endometrium and decidua, and these could represent stages 1 and 2 [22,23]. The decidua also contains CD56dimCD117+ cells that could correspond to stage 3 [32]. Uterine NK cells themselves are CD117+/−CD94+ and would thus correspond to stage 4.

Here, we report that NK developmental stages 3 and 4, but not stages 1 and 2, are present in the uterine mucosa. Uterine stage 3 cells are phenotypically identical to SLT stage 3 cells, produce IL-22 and can be induced to differentiate to stage 4 in culture, indicating that the final stage of uterine NK cell development occurs within the uterine microenvironment. This suggests that the uterine mucosa is a site of NK cell development.

Materials and methods

Primary tissue

The study was approved by the Ohio State University Institutional Review Board and the Cambridge LREC (study 04/Q0101/23) and all samples were obtained with informed consent. Buffy coats were from the UK National Blood Service.

Tonsils were minced, dispersed through 70μm cell strainers and layered on Ficoll (GE Healthcare) to enrich leukocytes. Cells were resuspended in MACS buffer (2mM EDTA and 1% BSA in PBS), treated with CD3 and CD19 MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec), passed through LD columns (Miltenyi Biotec) and the CD3-CD19-fraction retained.

Decidual leukocytes and trophoblast cells were isolated from first trimester termination samples (8 – 10 weeks) obtained by dilation and curettage. Endometrial leukocytes were isolated from Pipelle biopsies taken from normally cycling women undergoing tubal ligation. Both decidual and endometrial samples included the decidua functionalis, but not the basal layer or myometrium. Uterine leukocytes and trophoblasts were isolated as described [33]. Briefly, uterine tissue was minced and digested with collagenase IV (Sigma) (decidua: 10mg/ml, 1 hour, 37°C; endometrium: 0.6mg/ml, overnight, RT) and enriched for leukocytes by layering on Lymphoprep (Axis-Shield). For examination of stage 3 cells, staining was carried out immediately. For examination of CD34+ cells, the total leukocyte fraction was incubated for two hours at 37°C and the non-adherent fraction enriched for CD34+ cells using indirect CD34 MicroBeads and MS columns (Miltenyi Biotec). This enrichment was intended to reduce the number of CD34− cells falling into the CD34+ gate, in contrast to previous studies [22, 23].

Flow cytometry

Cells were blocked in 0.2mg/ml human gamma globulins (Sigma) and incubated with fluorochrome-conjugated antibody. For intracellular staining of IL-22, cells were pre-incubated for 4-8 hours with 10ug/ml Brefeldin (Sigma), cells were stained for CD117 and CD94, fixed in 5% paraformaldehyde (15 minutes, RT), washed twice in 0.1% saponin and incubated with intracellular antibody (30 minutes, RT in the dark), before two washes with saponin and one with PBS. Antibodies: CD94 clone 131412, NKp46, IL-22 (R&D); CD9, CD34 clone 581, CD161, LILRB1 (BD); CD3, CD56, KIR2DL1/S1 (Beckman Coulter); CD3, CD10, CD45, CD69, CD117 clone 104D2, CD122, ICAM-2, PECAM-1, NKp44, NKG2D (Biolegend); CD7, CD127 (eBioscience); CD45 (Sigma); CD19 (Dako) and matched isotype controls.

Cell sorting and culture

After overnight incubation to deplete adherent cells, CD117+ cells were pre-enriched using CD117-PE conjugated antibody (Biolegend) and EasySep PE selection kit (Stem Cell Technologies). Cells were stained for CD94 and CD3 expression. CD117+CD94−CD3− and CD117−CD94+CD3− populations were obtained by sorting on a MoFlo Cell Sorter. Cells were cultured for two weeks in alpha-MEM (Gibco) supplemented with 1nM recombinant IL-15 (Peprotech) and 10% FCS (Gibco), antibiotics (Sigma) and 2uM L-glutamine (Sigma), changing half the medium every three days. Blood leukocytes were processed immediately, enriched, stained and sorted as decidual leukocytes.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from decidual stage 3 and 4 cells using an RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen) and cDNA made using a Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche). PRC reaction: 1x Blue QPCR SYBR low ROX mix (Thermo Scientific), 70nM forward and reverse primers, 1ul cDNA (total volume 20ul). Cycling conditions: 2 minutes at 50°C, 1 cycle; 15 minutes at 95°C, 1 cycle; 15s at 95°C, 30s at 60°C, 32s at 72°C, 40 cycles.

GAPDH fwd: 5′-GTCGGAGTCAACGGATT-3′.

GAPDH rev: 5′-AAGCTTCCCGTTCTCAG-3′.

IL22 fwd: 5′-CCCATCAGCTCCCACTGC-3′.

IL22 rev: 5′-GGCACCACCTCCGCATATA-3′.

LTA fwd: 5′-CCAGCAAGCAGAACTCA-3′

LTA rev: 5′-ATGGGCCAGGTAGAGTG-3′

RORC was amplified with nested PCR reactions.

RORC outer fwd: 5′-CCCGTCAGCAGAACTG-3′.

RORC outer rev: 5′-AGCCCCAAGGTGTAGG-3′.

RORC inner fwd: 5′-GTCCCGAGATGCTGTCAAGT-3′.

RORC inner rev: 5′-TGAGGGTATCTGCTCCTTGG-3′

Immunohistochemistry

Frozen sections were stained using CD34 (BD), CD56 (Zymed) or appropriate isotype controls and the ImmPRESS staining system (Vector Laboratories), developed with DAB/hydrogen peroxide catalyst (Sigma) and counterstained with Carazzi’s hematoxylin. CD56 staining was included as a positive control (not shown). Images were acquired on a Leica DC500 camera-microscope using Leica IM50 Image Manager v1.20.

Results

The uterine mucosa contains stages 3 and 4 of NK cell development

In SLT, four stages of NK cell development are defined by expression of CD34, CD117 and CD94 [8]. Stage 1 cells are CD34+CD117−CD94−; stage 2 cells are CD34+CD117+CD94−; stage 3 cells are CD34−CD117+CD94−; stage 4 cells are CD34−CD117+/−CD94+ (Figure 1a). We initially confirmed that these stages could be identified in tonsillar leukocytes depleted of CD3+ and CD19+ cells (Figure 1b). Using the same staining procedure on total (undepleted) leukocytes from pregnant (decidual) or non-pregnant (endometrial) uterine mucosa, we identified both stage 3-like (CD117+CD94−) and stage 4-like (CD94+) populations, with stage 3-like cells accounting for 0.9–4.2% of cells in the leukocyte gate. Some of the cells identified as stage 3-like NK progenitor cells by CD117 and CD94 staining alone also expressed CD3 (9.5–32.9%, data not shown). In subsequent experiments CD3+ cells were therefore excluded from the analysis and stage 3-like cells defined as CD117+CD94−CD3−. CD94+ cells in the uterus, like SLT stage 4 cells, are CD117dim. These results demonstrate that decidua and endometrium, like SLT, contain CD117+CD94−CD3− stage 3-like cells, hereafter referred to as uterine stage 3 cells.

Multipotent stage 1 and 2 NK progenitor cells are not present in the uterine mucosa

Because the number of CD34+ cells was too small to visualize easily (0.6–0.8% of cells in the leukocyte gate, Supplementary Figure 1), they were enriched magnetically revealing a CD34+ population that, in contrast to SLT CD34+ stage 1 and 2 cells, was entirely CD117− (Figure 1c and –d). Therefore, unlike SLT, the uterine mucosa did not contain stage 2-like CD34+CD117+ cells, yet a CD34+ population that might contain stage 1 cells was clearly present. CD34 is not only a marker of multipotent hematopoietic cells but also stains endothelial cells. Immunohistology for CD34 in decidual sections revealed CD34+ cells exclusively lining vessels (Figure 2a and –b). Using flow cytometry, we also stained CD34+ cells for the leukocyte common antigen, CD45, and the adhesion molecules, PECAM-1 (CD31) and ICAM-2 (CD102), which are expressed at high levels on endothelial cells and at lower levels in some circulating CD45+ cells [34]. The results for CD34+ cells from endometrium and decidua were subtly different, probably reflecting the dramatic changes to the vasculature that occur during decidualization. However, CD34+ cells from both sources were uniformly negative for CD45 and were also ICAM-2 and PECAM-1 positive, consistent with an endothelial phenotype (Figure 2c-h). Therefore, multipotent stage 1 and 2 cells are absent in our preparations both before and during pregnancy.

Figure 2. CD34+ cells in the uterine mucosa are endothelial cells.

A and B: Serial sections of decidua stained for isotype control (A) and CD34 (B) showing positive staining on endothelial cells. C – E: Gating by scatter and on CD34+ endometrial cells, C, D and E show CD45, ICAM-2 and PECAM-1 staining, respectively. F – H: Phenotype of CD34+ decidual cells, as above. Antibody staining is shown by the bold trace, isotype control staining by a dotted line. Each dot plot is representative of at least three independent samples.

Uterine stage 3 cells are similar to SLT stage 3 cells and have the potential to differentiate into stage 4

We next undertook detailed phenotypic characterization of the uterine stage 3 cells, in order to compare them to the known phenotype of SLT stage 3 cells (Figure 3). Uterine stage 3 cells were CD45+, CD3− and CD19−, confirming their identity as leukocytes and suggesting they do not belong to either the T or B cell lineage. They were uniformly positive for the pan-species NK-lineage markers, NKp46 and CD161, and almost all positive for the human NK marker, CD56. Like their counterparts in SLT, uterine stage 3 cells were less CD56bright than CD94+ NK cells from the same sample, and also expressed NKp46 at a lower level. As a point of contrast, however, fewer stage 3-like cells were CD56− in the decidua than in SLT, indicating that uterine stage 3 cells as a population may be more mature.

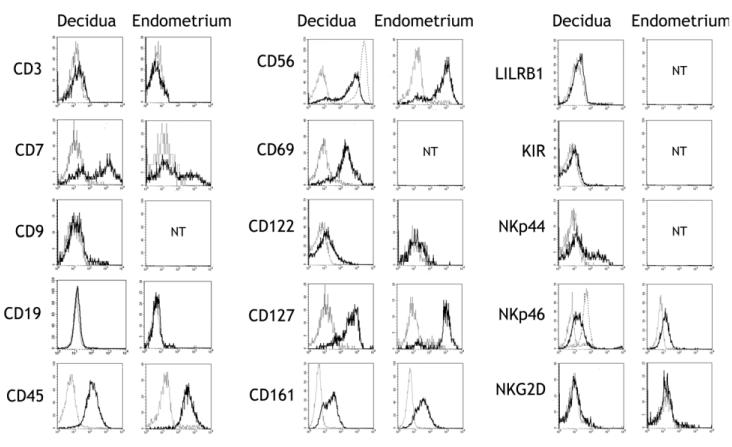

Figure 3. Uterine stage 3 cells are phenotypically similar to SLT stage 3.

Phenotype of CD117+CD94−CD3− cells in the decidua and endometrium. Antibody staining is shown by the bold trace, isotype control staining by a dotted line. For CD56 and NKp46, the level of staining on mature CD94+ decidual NK cells in the same sample is represented by a broken line. For decidua, each histogram represents one of at least three independent samples, examined for a single marker. For endometrium, each histogram represents a single sample, examined for a single marker. Endometrial samples were both proliferative and secretory phase. NT: not tested.

Decidual CD117+CD94−CD3− cells were also CD7+/−, CD69+, CD122low, CD127+/−, NKp44+/− and NKG2D−, similar to SLT stage 3 cells, thus displaying the phenotypic heterogeneity reported in this population [8,12,35]. The cells were also negative for the MHC class I-specific receptors LILRB1 and KIR, which are acquired late in NK cell development. CD9, a distinctive marker of mature decidual, but not resting peripheral, NK cells was not expressed [36]. Due to limited cell numbers, it was not possible to completely phenotype the uterine stage 3 cells from the non-pregnant endometrium, but for those markers examined they were identical to decidual and SLT stage 3 cells, that is: CD3−, CD7+/−, CD19−, CD45+, CD56+, CD122low, CD127+/−, CD161+, NKp46low, NKG2D− (Figure 3).

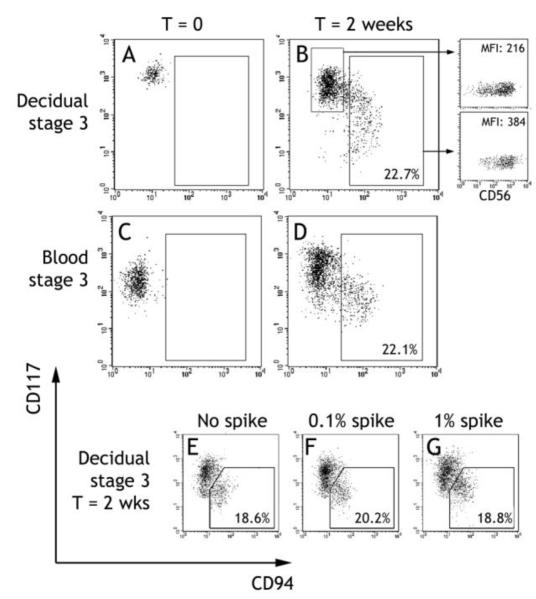

In vitro progression of SLT stage 3 cells to stage 4 is characterized by acquisition of CD94 and downregulation of CD117 [8,12]. To confirm that uterine stage 3 cells have similar NK precursor potential, decidual CD117+CD94−CD3− cells were cultured for 2 weeks with 1nM IL-15. A proportion (5.2–22.7%) of the cultured cells gained CD94 expression and lost some CD117 expression (Figure 4b), entirely consistent with similar experiments using SLT stage 3 cells [8]. The expression of CD56, another marker of NK maturation [8], also increased on acquisition of CD94+, providing further evidence that the cells are differentiating along the NK lineage (Figure 4b). To rule out the possibility that the CD94+ cells appearing after culture were an outgrowth of contaminating CD94+ cells, we deliberately introduced a “spike” of autologous sorted decidual CD94+ cells at the initiation of culture (Figure 4e-f). The maximum level of contamination in the starting stage 3 cells was 0.1%, but even after introducing 1% contamination there was no change in the proportion of cells in the CD94+ gate at the end of culture, discounting contamination.

Figure 4. NK cell potential of stage 3 cells isolated from uterine mucosa and peripheral blood.

A - D: CD117+CD94−CD3− stage 3 cells were sorted from CD117 enriched decidual (A) or peripheral blood (C) leukocytes. The sorted populations were cultured for two weeks in 1nM recombinant human IL-15 and re-examined for CD117 and CD94 expression by flow cytometry (B and D). Numbers indicate the percentage of cells falling into the gate. Cells recovered at the end of decidual cultures were examined for CD56 expression. The dot plots show CD56 staining against side scatter, for cells in the indicated gates, and mean fluorescence intensity is indicated (B). Each culture shown is representative of at least 3 independent experiments. E – F: Decidual CD117+CD94−CD3− cells were cultured as above, either alone or with the introduction of a 0.1% or 1% “spike” of sorted CD117−CD94+CD3− cells. The percentage of cells falling into the CD94+CD117low gate at the end of culture was determined by flow cytometry. Representative of 2 independent experiments.

We conclude that CD34−CD117+CD94−CD3− cells, which share the phenotype of the NK-committed precursors found in SLT, are present in the uterine mucosa and have NK cell progenitor potential.

Stage 3 cells are present in peripheral blood and can differentiate into stage 4 cells in vitro

Stage 3 cells have now been identified in two tissue locations: in the SLT [8] and in the uterine mucosa. Cells with a similar phenotype (CD117+CD94−) are also found in both umbilical cord [37] and adult peripheral blood [35]. We confirmed the latter observation, and found CD117+CD94−CD3− cells in peripheral blood, which accounted for around 0.01% of cells in the leukocyte gate. Further, after two weeks culture with 1nM IL-15, a proportion (9.6–22.1%) of blood CD117+CD94−CD3− cells were able to gain CD94 and lose CD117 expression (Figure 4d). Thus they may be circulating stage 3-like NK precursor cells, which could home to the uterine mucosa.

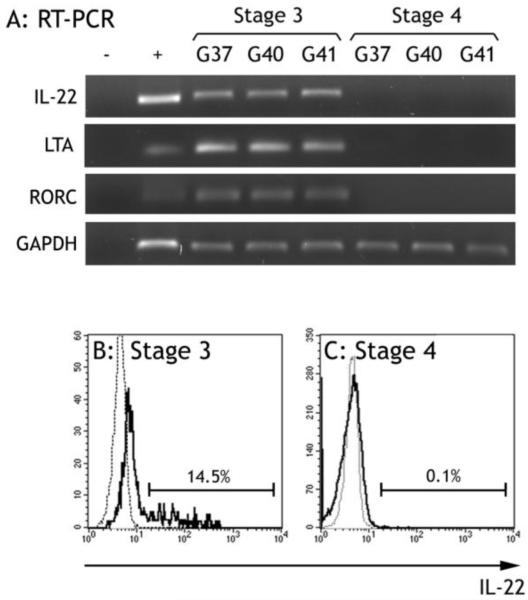

Uterine stage 3 cells constitutively produce IL-22

Interleukin 22-producing NK cells that phenotypically resemble stage 3 cells are present in the intestinal mucosa and SLT, and indeed a subset of SLT stage 3 cells are IL-22 producers [10-12, 39, 40]. We therefore tested whether uterine stage 3 cells were similar. By RT-PCR, uterine stage 3, but not stage 4, cells were positive for IL22 as well as the transcription factor involved in IL-22 induction, RORC [40]. Some cells in the uterine stage 3 population were also positive for LTA, which is expressed by lymphoid tissue inducer cells and also RORC+CD127+ NK-like cells, found within the CD117+ population in adult tonsil [40,11] (Figure 5a). By intracellular flow cytometry, a proportion of uterine stage 3 cells stained strongly for IL-22 (7.6–14.5%) but no stage 4 cells expressed the protein (Figure 5b and –c). In order to establish a function for IL-22 in the uterine mucosa, we looked for IL-22 receptor expression in sections by immunohistochemistry, and in isolated mucosal and placental cells by flow cytometry, but we were not able to detect expression of this receptor (data not shown).

Figure 5. Uterine stage 3 cells produce IL-22.

A: RT-PCR for IL22, LTA, RORC and GAPDH in three matched pairs of decidual stage 3 and 4 cells. pDNRdual-IL22, pDNRdual-LTA and pDNRdual-RORC (Invitrogen) were positive controls. The identities of the products were confirmed by sequencing. B and C: Intracellular staining for IL-22 on decidual stage 3 (B) and stage 4 (C) cells. Staining on stages 3 and 4 are represented by the bold trace, staining on CD3+ cells in the same sample is represented by a dotted line. Each histogram is representative of five independent experiments

Discussion

The NK cell population in the uterine mucosa undergoes a remarkable cyclical death and regeneration that raises the question of their origin, and there has been considerable debate as to whether they develop in utero. To address this question, we searched for stages 1 to 4 of NK cell development in the uterine mucosa and found that CD117+CD94−CD3− stage 3-like cells, and mature CD94+ cells that correspond to stage 4, are present both before and during pregnancy. On the other hand, the CD34+ cells present in our preparations were not leukocytes corresponding to stages 1 and 2 but were phenotypically and morphologically endothelial cells. The absence of CD34+CD45+ cells is in contrast to previous reports that such cells are present in the decidua and endometrium [23, 22]. The surgical samples we used in this study did not include the thin basal layer of the endometrium, and so it is still possible that CD34+ HSCs are present there, but this proviso also applies to the previous studies, which used similar tissues. Instead, it is likely that differences in experimental approach could account for these discrepancies.

Detailed phenotyping of uterine stage 3 cells revealed that they were negative for the T and B cell lineage markers CD3 and CD19, respectively, whereas they were uniformly positive for the NK lineage markers NKp46 and CD161, and almost all positive for the human NK lineage marker CD56. This phenotype strongly suggests that uterine stage 3 cells, like SLT stage 3, are committed to the NK lineage, although our results do not formally exclude the possibility of differentiation to other lineages. Uterine stage 3 cells were phenotypically similar to SLT stage 3 cells for all markers examined and were also able to differentiate to stage 4 when cultured with IL-15 in vitro, confirming that they are NK progenitor cells. IL-15 and other NK cell differentiation factors, such as kit ligand, are abundant in the endometrium and decidua [32,41] and so in vivo NK development in these locations is certainly possible. This is interesting for two reasons. Firstly, stage 3 NK precursor cells, capable of differentiating to stage 4 NK cells, have not previously been described in non-lymphoid tissue, indicating that the uterine mucosa could represent a novel site of NK cell development. Secondly, stage 3 cells do not express any NK cell receptors that recognize MHC class I molecules (CD94, LILRB1 and KIR). This means that during uNK development they must acquire the ability to recognize self MHC class I within this microenvironment, perhaps accounting for the unique uNK receptor repertoire, which is observed both in humans [19,42] and mice [43]. Indeed, mature uNK differ in a number of ways from mature SLT NK, implying that the environment in which the cells develop does shape their phenotype [8,17,19,35,36]. Furthermore, when NK differentiation occurs during pregnancy, the ability to recognize MHC class I will be acquired in the presence of the non-self paternal HLA-C expressed by placental trophoblast cells.

The presence of stage 3 cells in the uterus, where stages 1 and 2 are absent, raises the possibility that they have been recruited from the blood. We confirmed previous reports that CD117+CD94− cells are present in adult peripheral blood and do have NK progenitor potential [35]. Thus, they are likely to represent circulating NK precursor cells that could be recruited to the uterine mucosa. The precise timing and mechanism for stage 3 cell recruitment to the uterine mucosa will be an interesting point for further investigation. In this study, we observed that there were generally more uterine stage 3 cells in secretory endometrial samples than in either proliferative endometrium or decidua (data not shown). Together with evidence that uterine endothelial cells upregulate the expression of NK-attractive chemokines and adhesion molecules in response to progesterone, this suggests that stage 3 cells might be preferentially recruited during the secretory phase [24-27].

Stage 3-like cells were present in the blood of both male and female donors and could thus be recruited to other organs to further develop into mature NK cells. Whether stage 3-like cells are present at other sites that have a unique NK cell population, such as the liver [44], will be an interesting question to pursue. Stage 4 CD56bright NK cells could also be recruited from the blood to the uterus, but although recruitment of a mature cell and re-differentiation to a uNK phenotype cannot be ruled out, the presence of stage 3 cells makes it more likely that they are recruited and develop in utero.

The finding that, like SLT stage 3 cells, uterine NK cells express IL-22 is of interest because of the role of IL-22 in maintaining mucosal integrity, a function that is obviously important both during and outside reproductive life [39,45]. Although we were unable to detect IL-22 receptor in the uterine mucosa, this may have been due to sensitivity of the assay or that IL-22 signals through a different receptor at this location. Therefore, the possibility that IL-22 does have a role in the uterine mucosa cannot be ruled out.

The functional heterogeneity observed in uterine stage 3 cells, in which some are capable of differentiating to mature NK cells and some are IL-22 producers, is similar to that observed in SLT stage 3 cells [8,10,11,12]. This is reflected in phenotypic heterogeneity, in particular with respect to CD127, NKp44 and more recently IL-1RB [11,12,38]. Our uterine stage 3 cells displayed a similarly heterogeneous phenotype. Whether the IL-22 producing and conventional NK cells represent separate lineages is still debated, but our findings do clearly show that NK progenitors and IL-22 producing cells are present within the CD3-CD117+CD94− population. The presence of such cells in the uterine mucosa is particularly interesting because, arguably in contrast to the SLT, production of NK cells and mucosal homeostasis are both clearly required here. NK progenitor cells are necessary to give rise to the large numbers of characteristic uterine NK cells in response to ovarian hormones only at certain times during reproductive life. IL-22 producing cells, likely to be important in the shedding and regeneration of the mucosa during the menstrual cycle, may also be required in the static mucosa before the menarche and post-menopausally.

In summary, we have shown that CD117+CD94−CD3− cells phenotypically similar to SLT stage 3 cells are present in human uterine mucosa. This population contains some cells that have NK progenitor potential and some that are IL-22 producers, and both functions are likely to be important at this site. IL-22 producers might be essential for mucosal integrity in the face of cyclical breakdown and renewal of the mucosa, whereas NK progenitors are required for regenerating the cycling mature NK cell population. Since stage 3 cells are also present in the blood, we propose that these cells are recruited from the blood to the uterus, and there differentiate into mature uterine NK cells. Thus, the uterine mucosa is a novel site of NK development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Aharon Freud for critically reading the manuscript, Richard Apps and Andrew Sharkey for stimulating discussion, and Nigel Miller for help with cell sorting.

This work was funded by the Loke Wan Tho Studentship, awarded by King’s College, Cambridge, UK, and the Centre for Trophoblast Research, Cambridge, UK.

Non-standard abbreviations

- HSC

hematopoietic stem cell

- KIR

killer immunoglobulin-like receptor

- SLT

secondary lymphoid tissue

- uNK

uterine NK cell

References

- 1.Di Santo JP. Natural killer cell developmental pathways: a question of balance. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2006;24:257–86. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haller O, Wigzell H. Suppression of natural killer cell activity with radioactive strontium: effector cells are marrow dependent. J. Immunol. 1977;118:1503–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar V, Ben-Ezra J, Bennett M, Sonnenfeld G. Natural killer cells in mice treated with 89strontium: normal target-binding cell numbers but inability to kill even after interferon administration. J. Immunol. 1979;123:1832–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosmaraki EE, Douagi I, Roth C, Colucci F, Cumano A, Di Santo JP. Identification of committed NK cell progenitors in adult murine bone marrow. Eur. J. Immunol. 2001;31:1900–9. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200106)31:6<1900::aid-immu1900>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vosshenrich CA, Garcia-Ojeda ME, Samson-Villeger SI, Pasqualetto V, Enault L, Richard-Le-Goff O, Corcuff E, Guy-Grand D, Rocha B, Cumano A, Rogge L, Ezine S, Di Santo JP. A thymic pathway of mouse natural killer cell development characterized by expression of GATA-3 and CD127. Nat. Immunol. 2006;7:1217–24. doi: 10.1038/ni1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller JS, Verfaillie C, McGlave P. The generation of human natural killer cells from CD34+/DR− primitive progenitors in long-term bone marrow culture. Blood. 1992;80:2182–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller JS, Alley KA, McGlave P. Differentiation of natural killer (NK) cells from human primitive marrow progenitors in a stroma-based long-term culture system: identification of a CD34+7+ NK progenitor. Blood. 1994;83:2594–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freud AG, Yokohama A, Becknell B, Lee MT, Mao HC, Ferketich AK, Caligiuri MA. Evidence for discrete stages of human natural killer cell differentiation in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:1033–43. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freud AG, Becknell B, Roychowdhury S, Mao HC, Ferketich AK, Nuovo GJ, Hughes TL, Marbuger TB, Sung J, Baiocchi RA, Guimond M, Caligiuri MA. A human CD34(+) subset resides in lymph nodes and differentiates into CD56bright natural killer cells. Immunity. 2005;22:295–304. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hughes T, Becknell B, McClory S, Briercheck E, Freud AG, Zhang X, Mao H, Nuovo G, Yu J, Caligiuri MA. Stage 3 immature human natural killer cells found in secondary lymphoid tissue constitutively and selectively express the Th 17 cytokine interleukin-22. Blood. 2009;113:4008–10. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-192443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crellin NK, Trifari S, Kaplan CD, Cupedo T, Spits H. Human NKp44+IL-22+ cells and LTi-like cells constitute a stable RORC+ lineage distinct from conventional natural killer cells. J. Exp. Med. 2010;207:281–90. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hughes T, Becknell B, Freud AG, McClory S, Briercheck E, Yu J, Mao C, Giovenza C, Nuovo G, Wei L, Zhang X, Gavrilin MA, Wewers MD, Caligiuri MA. Interleukin-1β selectively expands and sustains interleukin-22+ immature human natural killer cells in secondary lymphoid tissue. Immunity. 2010;32:803–814. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Romagnani C, Juelke K, Falco M, Morandi B, D’Agostino A, Costa R, Ratto G, Forte G, Carrega P, Lui G, Conte R, Strowig T, Moretta A, Münz C, Thiel A, Moretta L, Ferlazzo G. CD56brightCD16− killer Ig-like receptor-NK cells display longer telomeres and acquire features of CD56dim NK cells upon activation. J Immunol. 2007;178:4947–55. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.4947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanna J, Goldman-Wohl D, Hamani Y, Avraham I, Greenfield C, Natanson-Yaron S, Prus D, Cohen-Daniel L, Arnon TI, Manaster I, Gazit R, Yutkin V, Benharroch D, Porgador A, Keshet E, Yagel S, Mandelboim O. Decidual NK cells regulate key developmental processes at the human fetal-maternal interface. Nat. Med. 2006;12:1065–74. doi: 10.1038/nm1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lash GE, Schiessl D, Kirkley M, Innes BA, Cooper A, Searle RF, Robson SC, Bulmer JN. Expression of angiogenic growth factors by uterine natural killer cells during early pregnancy. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2006;80:572–80. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0406250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cooper MA, Fehniger TA, Caligiuri MA. The biology of natural killer-cell subsets. Trends Immunol. 2001;22:633–40. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)02060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King A, Balendran N, Wooding P, Carter NP, Loke YW. CD3-leukocytes present in the human uterus during early placentation: phenotypic and morphologic characterization of the CD56++ population. Dev. Immunol. 1991;1:169–90. doi: 10.1155/1991/83493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.King A, Wooding P, Gardner L, Loke YW. Expression of perforin, granzyme A and TIA-1 by human uterine CD56+ NK cells implies they are activated and capable of effector functions. Hum. Reprod. 1993;8:2061–7. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verma S, King A, Loke YW. Expression of killer cell inhibitory receptors on human uterine natural killer cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 1997;27:979–83. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.King A, Wellings V, Gardner L, Loke YW. Immunocytochemical characterization of the unusual large granular lymphocytes in human endometrium throughout the menstrual cycle. Hum. Immunol. 1989;24:195–205. doi: 10.1016/0198-8859(89)90060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsuura-Sawada R, Murakami T, Ozawa Y, Nabeshima H, Akahira J, Sato Y, Koyanagi Y, Ito M, Terada Y, Okamura K. Reproduction of menstrual changes in transplanted human endometrial tissue in immunodeficient mice. Hum. Reprod. 2005;20:1477–84. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lynch L, Golden-Mason L, Eogan M, O’Herlihy C, O’Farrelly C. Cells with haematopoietic stem cell phenotype in adult human endometrium: relevance to infertility? Hum. Reprod. 2007;22:919–26. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keskin DB, Allen DS, Rybalov B, Andzelm MM, Stern JN, Kopcow HD, Koopman LA, Strominger JL. TGFbeta promotes conversion of CD16+ peripheral blood NK cells into CD16− NK cells with similarities to decidual NK cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104:3378–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611098104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kammerer U, von Wolff M, Markert UR. Immunology of human endometrium. Immunobiology. 2004;209:569–74. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sentman CL, Meadows SK, Wira CR, Eriksson M. Recruitment of uterine NK cells: induction of CXC chemokine ligands 10 and 11 in human endometrium by estradiol and progesterone. J. Immunol. 2004;173:6760–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.11.6760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamaguchi T, Kitaya K, Daikoko N, Yasuo T, Fushiki S, Honjo H. Potential selectin L ligands involved in selective recruitment of peripheral blood CD16(−) natural killer cells into human endometrium. Biol. Reprod. 2006;74:35–40. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.045971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carlino C, Stabile H, Morrone S, Bulla R, Soriani A, Agostinis C, Bossi F, Mocci C, Sarazani F, Tedesco F, Santoni A, Gismondi A. Recruitment of circulating NK cells through decidual tissues: a possible mechanism controlling NK cell accumulation in the uterus during early pregnancy. Blood. 2008;111:3108–15. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-105965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peel S, Stewart IJ, Bulmer D. Experimental evidence for the bone marrow origin of granulated metrial gland cells of the mouse uterus. Cell Tissue Res. 1983;233:647–56. doi: 10.1007/BF00212232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peel S, Stewart I. The differentiation of granulated metrial gland cells in chimeric mice and the effect of uterine shielding during irradiation. J. Anat. 1984;139:593–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chantakru S, Miller C, Roach LE, Kuziel WA, Maeda N, Wang WC, Evans SS, Croy BA. Contributions from self-renewal and trafficking to the uterine NK cell population of early pregnancy. J. Immunol. 2002;168:22–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saudemont A, Garçon F, Yadi H, Roche-Molina M, Kim N, Segonds-Pichon A, Martín-Fontecha A, Okkenhaug K, Colucci F. p110gamma and p110delta isoforms of phosphoinositide 3-kinase differentially regulate natural killer cell migration in health and disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:5795–800. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808594106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharkey AM, Jokhi PP, King A, Loke YW, Brown KD, Smith SK. Expression of c-kit and kit ligand at the human maternofetal interface. Cytokine. 1994;6:195–205. doi: 10.1016/1043-4666(94)90042-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Male V, Trundley A, Gardner L, Northfield J, Chang C, Moffett A. Natural killer cells in human pregnancy. Methods. Mol. Biol. 2010;612:447–63. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-362-6_30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barclay AN, Brown MH, Law SKA, McKnight AJ, Tomlinson MG, van der Merwe PA. The Leukocyte Antigen Facts Book. Academic Press; San Diego: 1997. pp. 206–8.pp. 377–8. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freud AG, Caligiuri MA. Human natural killer cell development. Immunol. Rev. 2006;214:56–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koopman LA, Kopcow HD, Rybalov B, Boyson JE, Oranger JS, Schatz F, Masch R, Lockwood CJ, Schachter AD, Park PJ, Strominger JL. Human decidual natural killer cells are a unique NK cell subset with immunomodulatory potential. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198:1201–12. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grzywacz B, Kataria N, Sikora M, Oostentorp RA, Dzierzak EA, Blazar BR, Miller JS, Verneris MR. Coordinated acquisition of inhibitory and activating receptors and functional properties by developing human natural killer cells. Blood. 2006;108:3824–33. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-020198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cella M, Otero K, Colonna M. Expansion of human NK-22 cells with IL-7, IL-2, and IL-1β reveals intrinsic functional plasticity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:10961–10966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005641107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cella M, Fuchs A, Vermi W, Facchetti F, Otero K, Lennerz JK, Doherty JM, Mills JC, Colonna M. A human natural killer cell subset provides an innate source of IL-22 for mucosal immunity. Nature. 2009;457:722–5. doi: 10.1038/nature07537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cupedo T, Crellin NK, Papazian N, Rombouts EJ, Weijer K, Grogan JL, Fibbe WE, Cornelissen JJ, Spits H. Human fetal lymphoid tissue-inducer cells are interleukin 17-producing precursors to RORC+ CD127+ natural killer-like cells. Nat. Immunol. 2009;10:66–74. doi: 10.1038/ni.1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Verma S, Hiby SE, Loke YW, King A. Human Decidual Natural Killer Cells Express the Receptor for and Respond to the Cytokine Interleukin 15. Biol. Reprod. 2000;62:959–968. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod62.4.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharkey AM, Gardner L, Hiby S, Farrell L, Apps R, Master L, Goodridge J, Lathbury L, Stewart CA, Verma S, Moffett A. Killer Ig-like receptor expression in uterine NK cells is biased toward recognition of HLA-C and alters with gestational age. J. Immunol. 2008;181:39–46. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yadi H, Burke S, Madeja Z, Hemberger M, Moffett A, Colucci F. Unique receptor repertoire in mouse uterine NK cells. J. Immunol. 2008;181:6140–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.6140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burt BM, Plitas G, Zhao Z, Bamboat ZM, Nguyen HM, Dupont B, DeMatteo RP. The Lytic Potential of Human Liver NK Cells Is Restricted by Their Limited Expression of Inhibitory Killer Ig-Like Receptors. J. Immunol. 2009;183:1789–96. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Satoh-Takayama N, Vosshenrich CA, Lesjean-Pottier S, Sawa S, Lochner M, Rattis F, Mention JJ, Thiam K, Cerf-Bensussan N, Mandelboim O, Eberl G, Di Santo JP. Microbial flora drives interleukin-22 production in intestinal NKp46+ cells that provide innate mucosal immune defense. Immunity. 2008;29:958–70. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.