Abstract

Introduction

The AHA 2020 Strategic Impact Goal proposes a 20% improvement in cardiovascular health of all Americans. We aimed to estimate the potential reduction in coronary heart disease (CHD) deaths.

Methods and Results

We used data on 40,373 CVD-free adults from NHANES (1988–2010). We quantified recent trends for six metrics (total cholesterol [TC]; systolic blood pressure [SBP]; physical inactivity; smoking; diabetes; obesity) and generated linear projections to 2020. We projected the expected number of CHD deaths in 2020 if 2006 age- and sex-specific CHD death rates remained constant, which would result in approximately 480,000 CHD deaths in 2020 (12% increase). We used the previously validated IMPACT CHD model to project numbers of CHD deaths in 2020 under two different scenarios.

A) Assuming a 20% improvement in each CVH metric, we project 365,000 CHD deaths in 2020, (range 327,000–403,000) a 24% decrease reflecting modest reductions in TC (−41,000), SBP (−36,000), physical inactivity (−12,000), smoking (−10,000), diabetes (−10,000), and obesity (−5,000). B) Assuming that recent risk factor trends continue to 2020, we project 335,000 CHD deaths (range 274,000–386,000), a 30% decrease reflecting improvements in TC, SBP, smoking and physical activity (~167,000 fewer deaths), offset by increases in diabetes and BMI (~24,000 more deaths).

Conclusions

Two contrasting scenarios of change in CVH metrics could prevent 24–30% of the CHD deaths expected in 2020, though with differing impacts by age. Unfavorable continuing trends in obesity and diabetes would have substantial adverse effects. This analysis demonstrates the utility of modelling to inform health policy.

Keywords: heart disease, American Heart Association, epidemiology, risk factor

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) death rates have fallen dramatically in the US since the 1960s.1,2 Our prior work indicates that these mortality declines reflect both decreases in population risk factor levels (due to public health, environmental and behavioral changes) and clinical application of evidence-based therapies.3 However, CVD remains the leading cause of US mortality, accounting for nearly 800,000 deaths and 6 million hospital discharges annually.2 Previously falling CVD death rates have now plateaued in younger adults and obesity and diabetes are increasing.2,4 If these adverse trends continue, the annual direct US costs of CVD could reach $820 billion by 2030.5

In response to these trends, the American Heart Association (AHA) has recently defined and outlined its 2020 Strategic Impact Goal of achieving a 20% reduction in cardiovascular and stroke deaths and a 20% improvement in cardiovascular health (CVH) of all Americans by 2020. CVH is defined in terms of 7 metrics: 4 health behaviors (smoking, diet, physical activity, body mass index [BMI]) and 3 health factors (plasma glucose, cholesterol, blood pressure).6

Numerous studies have affirmed the relevance of this new CVH paradigm through their description of a robust, stepwise association between greater levels of CVH and lower event rates, including ischemic heart disease, cardiovascular disease, and all-cause mortality7,8 and non-fatal CVD events.9–11 We recently projected forward, linear trends using NHANES data in each of these metrics to 2020 and estimated that if current trends were to continue unaltered, CVH would improve by only 6%.12

We have previously used our US IMPACT CHD policy model to explain prior trends in CHD mortality between 1980 and 20003 and to project future trends in CHD mortality.13 In the present study, we sought to estimate potential reductions in CHD mortality by 2020 under two contrasting risk factor scenarios: A) assuming a 20% relative improvement in each of 6 metrics (diet score excluded due to modelling limitations), and B) assuming recent (1988–2010) trends in these CVH metrics continue.

METHODS

The US IMPACT CHD Model

The US IMPACT CHD Model is a spreadsheet-based model, which uses epidemiologic data and extensive systematic literature reviews to quantify estimates of CHD mortality impacts of evidence-based medical and procedural treatments and population risk factor reductions under operator-defined scenarios.3 It was developed to help explain population-level changes in CHD death rates over time. The model includes more than 60 covariates overall, six of which serve to quantify changes in population levels of health behaviors and factors, specifically smoking, cholesterol, blood pressure, body mass index (BMI), diabetes, and physical inactivity (six of the seven metrics for measurement of CVH, as defined by the American Heart Association [see Data Supplement for definitions of CVH metrics]). The model also includes over 50 covariates that quantify changes in all standard medical treatments such as acute therapies for myocardial infarction including aspirin, beta blockers, statins, heparin, thrombolysis, percutaneous coronary intervention, and coronary artery bypass graft surgery, as well as chronic drug therapies for primary and secondary prevention therapy with aspirin, statins, and blood pressure lowering therapies.

The IMPACT CHD model employs beta coefficients derived from large meta-analyses to provide effect size estimates for continuous variables (blood pressure [per 20 mmHg change], cholesterol [per 1 mmol/L change], and BMI [per 1 kg/m2 change]). Coefficients are assumed to be independent since prior meta-analyses used as data sources adjusted for potential confounders, including other major risk factors. For each continuously distributed risk factor, changes in mortality from 2006 to 2020 could be estimated by multiplying three variables:

Number of CHD deaths attributable to RF = CHD deaths x the risk factor change x specific regression coefficient exponentiated3,14–17

The IMPACT CHD model uses population-attributable risk fraction effect size estimates for prevalence, or categorical variables such as smoking, diabetes, or physical inactivity to evaluate the impact of changes in these variables on CHD death.15–17 The population attributable risk fraction estimates for CHD are based on data from the INTERHEART study, which accounted for potential confounders. Changes in mortality from the base year used by the AHA Strategic Impact Goals committee (2006) to 2020 for each prevalence variable were calculated:

Number of CHD deaths attributable to RF = CHD deaths x [P x (RR-1) / [1+ P(RR-1)], where P = prevalence change of risk factors and RR = relative risk of CHD death

For example, for men between the ages of 65 and 74 years, the OR associated with CHD death is 2.52, the smoking prevalence in 2005–2006 was 14.7%, and the number of CHD deaths was 42,848 deaths. Using the above formula, the estimated number of CHD deaths in 2006 attributable to smoking is:

The difference between 2020 and 2006 attributable deaths for each variable is taken to estimate the number of deaths prevented or postponed (DPPs). Total deaths from changes in categorical variables can then be summed to provide an estimate of deaths prevented or postponed for comparison with the reference estimate that accounts for population aging, without any change in risk factors or medical or surgical treatments.

For the present analysis, we first extended the original 1980–2000 US IMPACT USA CHD model to 2020, using United States Census Bureau population projections and mortality data for men and women aged 25–85+ years. The number of CHD deaths (International Classification of Diseases, ICD-10: I20-I25) expected in 2020 was calculated under baseline conditions, assuming that the age-specific mortality rates in 2006 persisted unchanged to 2020. We explored other counterfactual baseline scenarios, such as projecting CHD death rates in a linear fashion to 2020 and by creating hierarchical Bayesian age-period cohort (APC) models to estimate CHD death rates in 2020. These methods produced either implausible (rates below zero, e.g.) or highly unstable estimates. We chose to use 2006 CHD death rates based on these limitations and for sake of simplicity.

Next, the deaths potentially observed under each of two risk factor scenarios were then estimated as follows:

Risk Factor Scenarios

For Scenario A, representing a 20% improvement in overall CVH, we assumed a 20% improvement in each metric as defined by the AHA using data from 40,373 CVD-free adults (≥ 20 years) examined in NHANES from 1988 to 2010 (see Data Supplement for participant flowchart). Methods of measurement of each health behavior and health factor have been previously reported and are described in the Data Supplement. We assumed a 20% improvement in categorical variables by decreasing the prevalence of poor CVH by 20% and increasing the prevalence of ideal CVH by 20%. The prevalence of intermediate CVH was then estimated by subtracting the prevalence of poor and ideal health prevalence estimates from 100%.

To estimate a 20% change in a continuous variable such as blood pressure, cholesterol, or body mass index in the construct of ideal, intermediate, and poor cardiovascular health categories, we projected a 20% increase in the proportion of individuals in the ideal CVH category and a 20% decrease in the proportion of individuals in the poor CVH category across age and sex strata. We assumed that the mean level of each CVH metric in ideal, intermediate, and poor levels would remain the same, but the projected change in proportion of ideal, intermediate, and poor levels would change the age- and sex-stratified mean level for each CVH metric. This age- and sex-stratified CVH metric mean was then compared against the baseline mean to input into the IMPACT CHD model.

For Scenario B, we assumed that recent risk factor trends would continue to 2020 based on forward linear projections. We quantified recent temporal trends in six of seven CVH metrics by age and sex, using the most recent available data from NHANES (1988–2010). (We could not include the diet score metric because the underlying data are not yet included in the IMPACT Model.) We then generated forward projections to 2020 for population CVH behavior and factor levels.12 We used 2006 as the base year since the AHA Strategic Impact Goal defines 2006 as its base year.

NHANES trends analyses were performed using SAS v9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) taking into account the complex sampling design. We estimated time trends from 1988 to 2010 and average annual change in CVH behaviors and factors by weighted linear regression using estimated mean values or percentages as dependent variables and survey times as independent variables, as previously reported.12 We fitted our regression models with the prevalence as the dependent variables and survey time as independent variables. We used the beta coefficients to estimate average annual change in the prevalence of ideal, intermediate, and poor levels of CVH for each metric. We projected estimates to 2020 by assuming that trends would continue similarly to those observed over the past two decades in a linear fashion based on standard error (SE) of the predicted prevalence estimates.12 We used reciprocals of variances as weights. We assessed non-linear projections, but the results were similar except for blood pressure trends in women, which produced an implausibly low estimate. We chose linear projections for simplicity as in our recently published analyses through 2008.12

For both scenarios and all sensitivity analyses, we conservatively assumed the prevalence of medical and surgical treatments for CHD would remain constant.

Comparisons of numbers of deaths in 2020, with sensitivity analyses

Finally, following these steps, we compared the numbers of deaths projected under each Scenario, A and B, with the reference value estimated as above. This included multi-way sensitivity analyses using the analysis of extremes method.18 We generated minimum and maximum estimates of deaths prevented or postponed using minimum and maximum plausible values for the main parameters: 95% confidence intervals (CIs) when available; otherwise, the best value ± 20%. Examples of the calculations used in the model and further details on the methods and data sources have been previously reported.19

RESULTS

Trends and Estimates in CHD Mortality and Risk Factors

CVH behavior and health factor estimates for 1988–1994, 2006, and 2020 under both scenarios, separate for men and women, are shown in Table 1. The main findings are the values for each metric in 2020, under the two alternative scenarios, relative to those in 2006. Noteworthy are the contrasts in body mass index and diabetes prevalence: each would decrease under Scenario A but would continue to increase under Scenario B. For physical inactivity, the degree of decrease would be greater under Scenario B than the more modest 20% decrease in Scenario A. Age and sex-stratified estimates for CVH behaviors and health factors in 2006 and 2020 projections under both scenarios are available in the Data Supplement Tables 1–6.

Table 1.

Cardiovascular risk factor levels in base year 2005–6 and projections to 2020 under two cardiovascular risk factor change scenarios.

| Smoking prevalence, % |

Mean total Cholesterol (mmol/L) |

Mean systolic blood pressure (mmHg) |

Mean body mass index (kg/m2) |

Diabetes prevalence, % |

Physical inactivity prevalence, %* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factor scenario |

Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women |

| NHANES III (1988–1994) | 30.8 | 25.3 | 5.25 | 5.37 | 124.8 | 120.8 | 26.8 | 26.7 | 4.3 | 5.5 | 38.2 | 43.4 |

| In 2006 (NHANES 2005–6) | 25.7 | 19.0 | 5.18 | 5.29 | 124.3 | 122.0 | 28.6 | 28.4 | 6.5 | 7.4 | 32.1 | 33.7 |

| Scenario A | ||||||||||||

| In 2020, if 20% reduction is assumed for each metric* | 20.5 | 15.2 | 4.96 | 5.14 | 119.9 | 119.4 | 27.9 | 27.4 | 5.2 | 5.9 | 25.7 | 27.0 |

| Scenario B | ||||||||||||

| In 2020, if recent trends continue | 20.9 | 14.6 | 5.01 | 5.04 | 119.1 | 119.9 | 30.3 | 30.0 | 9.7 | 8.7 | 19.4 | 6.7** |

Defined as 20% improvement in each individual metric.

Trends for physical activity are based on data from 1999–2006 examination cycle due to changes in the methods by which physical activity was captured before 1999 and after 2006.

Approximately 478,760 CHD deaths among individuals aged 25 years and older would be expected in 2020 if the same age- and sex-specific death rates recorded in 200620 persisted unchanged in 2020 (Table 2, column 6) This number represents 53,543 (12.6%) more CHD deaths than the 425,215 observed in 2006 (base year), reflecting population growth and aging.

Table 2.

Age-specific CHD mortality rates and CHD deaths observed in 2006 and projections to 2020 based on population growth and aging, assuming risk factors are held constant (baseline scenario).

| Age group, years |

Population in 2006 (x 1,000) |

CHD mortality rate observed in 2006 per 100,000 |

Number of CHD deaths in 2006 |

Population projected in 2020 (x 1,000) |

Expected number of CHD deaths in 2020 if 2006 mortality rate constant |

Projected differences in numbers of CHD deaths in 2020 vs. 2006 |

Percent change in CHD deaths in 2020 from 2006 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | |||||||

| 25–34 | 20,565 | 4.0 | 829 | 19,958 | 798 | −31 | −3.7% |

| 35–44 | 21,850 | 23.2 | 5,075 | 24,393 | 5,659 | 584 | 11.5% |

| 45–54 | 21,290 | 89.1 | 18,972 | 24,514 | 21,842 | 2,870 | 15.1% |

| 55–64 | 15,224 | 220.7 | 33,593 | 18,386 | 40,577 | 6,984 | 20.8% |

| 65–74 | 8,670 | 494.2 | 42,848 | 11,988 | 59,244 | 16,396 | 38.3% |

| 75–84 | 5,298 | 1269.7 | 67,275 | 8,718 | 110,698 | 43,423 | 64.5% |

| 85+ | 1,688 | 3,303.0 | 55,763 | 2,342 | 77,356 | 21,593 | 38.7% |

| Subtotal | 94,585 | 237.2 | 224,355 | 107,956 | 256,070 | 31,715 | 14.1% |

| Women | |||||||

| 25–34 | 19,851 | 1.1 | 225 | 19,569 | 215 | −10 | −4.3% |

| 35–44 | 21,817 | 7.4 | 1,624 | 23,918 | 1,770 | 146 | 9.0% |

| 45–54 | 21,989 | 27.4 | 6,018 | 25,465 | 6,977 | 959 | 15.9% |

| 55–64 | 16,363 | 80.1 | 13,113 | 19,099 | 15,298 | 2,185 | 16.7% |

| 65–74 | 10,247 | 232.6 | 23,837 | 14,251 | 33,148 | 9,311 | 39.1% |

| 75–84 | 7,748 | 747.9 | 57,950 | 10,364 | 77,515 | 19,565 | 33.8% |

| 85+ | 3,609 | 2,718.3 | 98,092 | 4,248 | 115,473 | 17,381 | 17.7% |

| Subtotal | 101,623 | 197.7 | 200,859 | 112,667 | 222,687 | 21,828 | 10.9% |

| TOTAL | 196,208 | 216.7 | 425,214 | 220,623 | 478,760 | 53,543 | 12.6% |

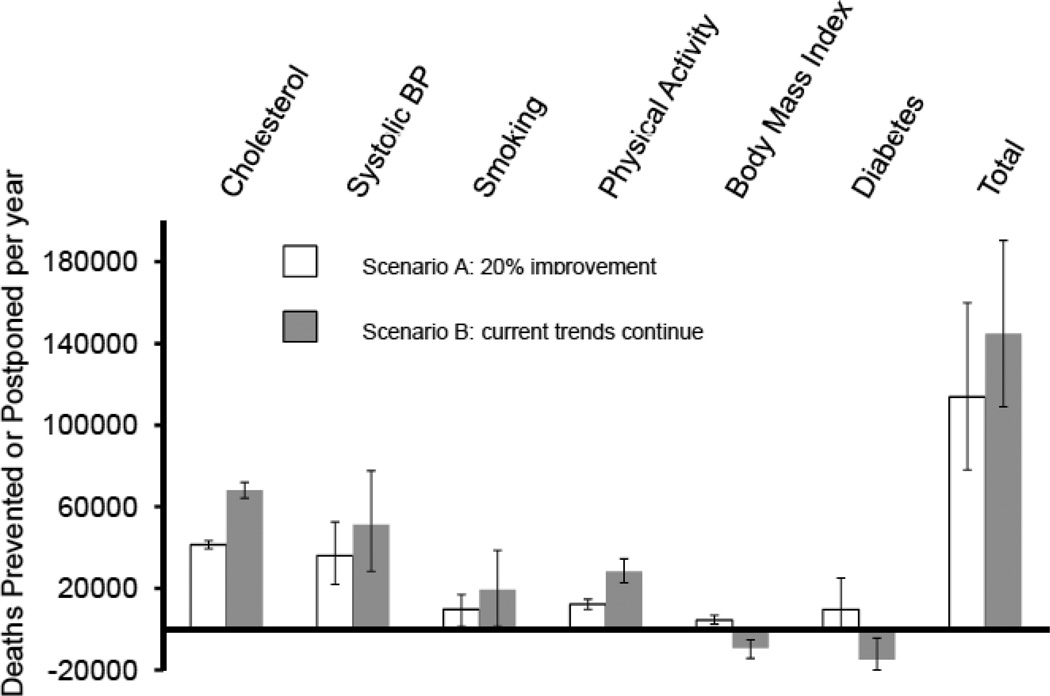

Scenario A: Achieving AHA Strategic Impact Goal through 20% Improvement in Each Metric (Table 3, Figure 1)

Table 3.

CHD deaths in 2020 as a change from 2006 baseline, by sex, under two cardiovascular risk factor scenarios.

| Risk factor value | CHD deaths in 2020 compared with base scenario if 2006 death rates applied to expanded population of 2020 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Both sexes | Best estimate | ||||||

| Risk factor scenario | Men | Women | Best estimate | Minimum estimate |

Maximum estimate |

Men | Women |

| Smoking prevalence, % | |||||||

| In 2006 | 25.7 | 19.0 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| If AHA 2020 goal achieved* | 20.5 | 15.2 | −9,840 | −7,870 | −11,805 | −6,510 | −3,325 |

| If recent trends continue to 2020 | 20.9 | 14.6 | −19,455 | −15,565 | −23,345 | −11,750 | −7,705 |

| Mean TC, mmol/L | |||||||

| In 2006 | 5.18 | 5.29 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| If AHA 2020 goal achieved* | 4.96 | 5.14 | −41,465 | −27,480 | −58,020 | −18,605 | −22,860 |

| If recent trends continue to 2020 | 5.01 | 5.04 | −68,165 | −45,450 | −94,620 | −29,710 | −38,455 |

| Mean SBP, mmHg | |||||||

| In 2006 | 124.3 | 122.0 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| If AHA 2020 goal achieved* | 119.9 | 119.4 | −36,050 | −27,605 | −43,225 | −18,260 | −17,790 |

| If recent trends continue to 2020 | 119.1 | 119.9 | −51,235 | −33,195 | −68,440 | −28,915 | −22,320 |

| Mean BMI, kg/m2 | |||||||

| In 2006 | 28.6 | 28.4 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| If AHA 2020 goal achieved* | 27.9 | 27.4 | −4,545 | −2,565 | −6,975 | −2,370 | −2,170 |

| If recent trends continue to 2020 | 30.3 | 30.0 | 9,090 | 5,085 | 14,120 | 5,780 | 3,310 |

| Diabetes prevalence, % | |||||||

| In 2006 | 6.5 | 7.4 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| If AHA 2020 goal achieved* | 5.2 | 5.9 | −9,670 | −165 | −16,500 | −3,810 | −5,860 |

| If recent trends continue to 2020 | 9.7 | 8.5 | 14,805 | 4,230 | 19,860 | 12,040 | 2,770 |

| Physical inactivity prevalence, % | |||||||

| In 2006 | 32.1 | 33.7 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| If AHA 2020 goal achieved* | 25.7 | 27.0 | −12,295 | −9,835 | −14,750 | −4,360 | −7,935 |

| If recent trends continue to 2020 | 19.4 | 6.7 | −28,430 | −22,805 | −34,585 | −10,455 | −17,970 |

| Total | |||||||

| In 2006 (actual) | -- | -- | (425,215) | -- | -- | (224,355) | (200,860) |

| Projected deaths in 2020 | -- | -- | (478,760) | -- | -- | (256,070) | (222,690) |

| If AHA 2020 goal achieved* | -- | -- | −113,860 | −75,520 | −151,290 | −53,920 | −59,940 |

| If recent trends continue to 2020 | -- | -- | −143,390 | −92,270 | −204,760 | −63,010 | −80,380 |

Defined as 20% improvement in each individual metric.

Figure 1.

Estimated number of CHD deaths prevented or postponed in 2020, by cardiovascular risk factor, under two different risk factor scenarios. *Defined as 20% improvement in each individual metric.

A 20% improvement in each metric would result in the following estimates: a) 36,050 (range, 27,605 – 42,235) fewer deaths due to a 2.8 mmHg reduction in blood pressure in men and women; b) 9,840 fewer deaths (range, 7,870 – 11,805) due to a 4.5% absolute decrease in the prevalence of smoking; c) 41,465 fewer deaths (range, 27,480 – 58,020) due to a 0.18 mmol/L (7.0 mg/dL) decrease in total cholesterol; d) 4,545 fewer deaths (range, 2,565 – 6,975) due to a 0.9 kg/m2 decrease in mean BMI; e) 9,670 fewer deaths (range, 165 – 16,500) due to a 1.3% decrease in the prevalence of diabetes; and f) 12,295 fewer deaths (range, 9,835 – 14,750) due to a 6.5% decrease in the prevalence of physical inactivity. Altogether, 364,900 CHD deaths (range 327,470–403,240) would be expected in 2020, under Scenario A, 24% fewer than expected in 2020 under the reference projection.

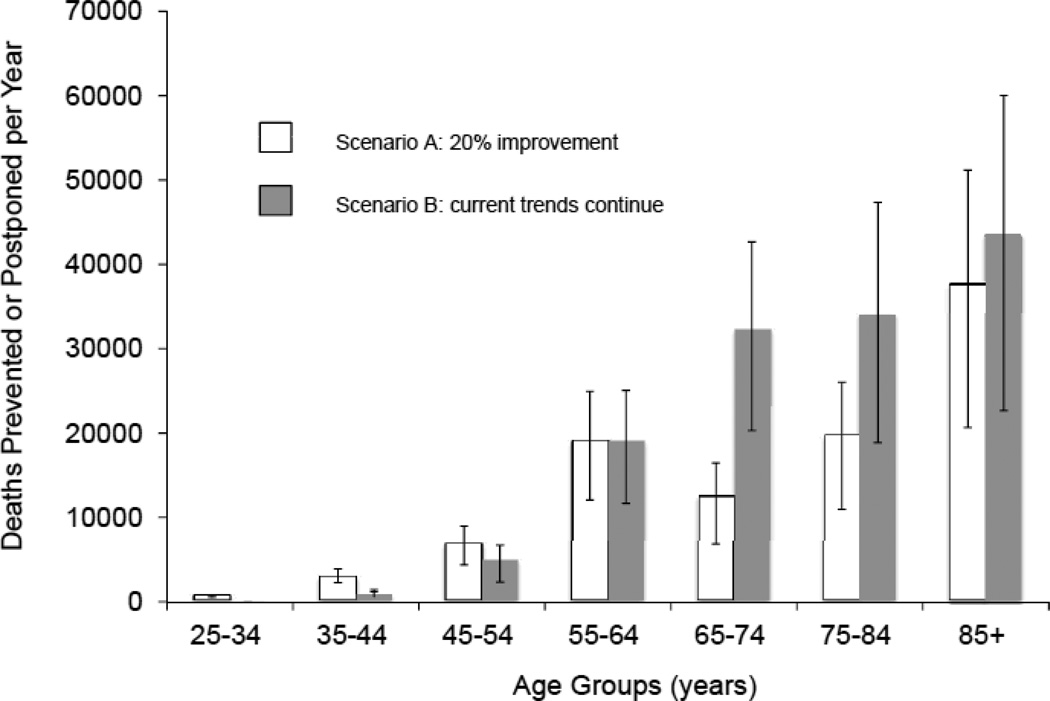

The 113,860 fewer deaths observed than expected under this scenario would comprise 53,920 fewer deaths (range, 36,145 – 78,815) in men compared with 59,940 (range, 39,375 – 76,460) fewer deaths in women (Table 3). The relation of the health factor effects with age is shown in Figure 2. As would be anticipated, improvements would occur predominantly in older individuals, those aged 55 years and older, since these age groups have the highest number of absolute CHD deaths (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Estimated number of CHD deaths prevented or postponed in 2020, by age groups, under two different risk factor scenarios. *Defined as 20% improvement in each individual metric.

Scenario B: If Current Risk Factor Trends Continue (Table 3, Figure 1)

A continuation of current trends in CVH metrics from 1988–2010 projected to 2020 would result in the following estimates: a) 51,235 (range, 33,195, 70,555) fewer deaths due to a 2.9 mmHg decrease in systolic blood pressure; b) 19,455 (range, 15,565, 23,345) fewer deaths due to a 4.6% decrease in the absolute prevalence of smoking; c) 68,165 (range, 45,450, 94,620) fewer deaths due to a 0.21 mmol/L (8.1 mg/dL) decrease in total cholesterol; and d) 28,430 (range, 22,805, 34,585) fewer deaths due to a 20.1% decrease in the prevalence of physical inactivity. The adverse trends in body weight and diabetes would result in 9,900 (range, −5,085, −14,120) additional deaths due to a 1.6 kg/m2 average increase in BMI; and 14,805 (range, −4,230, −19,860) additional deaths due to a 2.3% absolute increase in the prevalence of diabetes. In a secondary analysis, given the instability and implausibility of the estimates for physical inactivity in women, we doubled the 2020 forward projection from 6.7% to 13.4% with minimal change in our overall estimates (data not shown).

Altogether, 335,000 CHD deaths (range, 274,000–386,000) would be expected in 2020, under Scenario B, 30% fewer than expected in 2020 under the reference projection. Approximately 63,010 (range, 41,015, 98,525) fewer deaths are estimated in men compared with some 80,380 (range, 51,050, 115,480) fewer deaths in women (Table 3). Improvements would again predominantly occur in older individuals aged 55 years and older (Figure 2).

Sensitivity Analyses

Using extensive sensitivity analyses, we examined the impact of higher and lower values for model inputs.18 This changed the absolute number of deaths but not the rank order of benefit across CV health metrics (Figure 1): under both scenarios, the biggest projected benefits would consistently come from improvements in cholesterol and blood pressure.

DISCUSSION

These findings suggest that the default projection to 2020 might result in more than 50,000 additional CHD deaths above the 2006 baseline. Conversely, risk factor improvements among persons with no history of major CVD could in principle reduce CHD deaths in 2020 by 24% to 30% in either of two ways. Scenarios A and B both predict major benefits from decreases in population mean values of total cholesterol and systolic blood pressure. Both also include a strong relation between impact and age, being greater at successively older ages.

Scenario A anticipates a reduction in the prevalence of both obesity and diabetes, while Scenario B reasonably predicts an increase. Hence the greater overall impact of Scenario A than B in improvement of total cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, smoking, and physical activity. The scenarios also differ in their impact at different ages. The majority of CHD deaths occur in individuals > 55 years, who currently have more favourable trends in some CVH metrics than do younger individuals (Data Supplement). A 20% reduction for all risk factors (Scenario A) would represent greater improvements at younger ages than has been observed occurred in recent trends. Conversely, continuation of recent trends would have greater impact on older persons at greater CHD risk (Scenario B). This may explain the somewhat lesser overall effect on CHD deaths in 2020 predicted under Scenario A. (shown in detail in Supplemental Tables 2–7).

These results have major implications for both for policy and future research. The policy implications are that: (1) substantial benefit to the U.S. population would be predicted from improvement in CVH metrics from their level in 2006; (2) continuation of recent trends is necessary to have the maximum effect, will chiefly benefit older persons, and warrants strong continuing efforts to sustain those trends; (3) only a policy of improving CVH metrics for all Americans would be expected to reverse the trends in obesity and diabetes and to confer potential benefit on younger persons. That benefit would be realized increasingly beyond 2020.

In terms of research implications: (1) analyses using the IMPACT CHD Policy Model demonstrates the utility of modeling approaches in helping understand how improving the cardiovascular health of all Americans may impact the second goal of reducing cardiovascular and stroke deaths; (2) broadening the model to encompass other cardiovascular and stroke outcomes and to incorporate dietary components will add importantly to its value; and (3) other alternative scenarios of improving CVH metrics under the AHA 2020 Impact Goal could be similarly explored, further informing critical policy decisions for the nation's health.

These data may provide guidance to the AHA and other policymakers and programs such as the Million Hearts Initiative on how to balance complementary strategies for the dual goal of improving CVH and of reducing CVD deaths. Older individuals have higher absolute risks of CHD death. They might therefore gain greater absolute CHD mortality benefits from both population and high-risk approaches than younger individuals despite similar relative risk reductions. Longer-term gains from improved CVH are expected in younger and middle-aged individuals, as they could realize gains seen in “low-risk” individuals with optimal health factors21 and health behaviors22 over a longer remaining lifespan. However, recent increases in CHD mortality among younger US men and women4 suggest that some younger individuals might also derive short-term reductions in CHD deaths through improved CVH.23 Beyond CHD alone, an interaction between CVH and age on CVD mortality has been recently observed, suggesting that ideal CVH may provide greater relative protection against CVD death in younger compared with older Americans.8

The AHA 2020 Strategic Impact Goal represents an important conceptual step in promoting the concept of CVH. Our data suggest that in order to reach the 2020 Strategic Impact Goal of improving CVH by 20% while also reducing cardiovascular deaths by at least 20%, the AHA should attempt to augment current, favorable trends in cholesterol and blood pressure, while focusing new efforts on improving trends in BMI, diabetes, and smoking throughout the lifecourse, which are also drivers of other cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular events, including non-fatal myocardial infarction, heart failure, and stroke, which are important endpoints not evaluated in our US IMPACT CHD model. Therefore, these findings reinforce the concept of a balance between high-risk and population-based approaches to disease prevention and health promotion, as proposed by Rose.24

We recognize that a 20% improvement in overall CVH might be more feasibly achieved through other combinations of changes in CVH metrics. For example, if obesity prevalence remains flat (0% change), then a >20% improvement would be needed in other metrics to achieve the AHA’s 2020 goal. We anticipate further analyses to explore such alternative scenarios.

Strengths/Limitations

The strengths of our study include the use of nationally representative sample over a twenty-year period of data collection and the use of the US IMPACT CHD model. Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, future trends in risk factor levels and prevalences may be non-linear. Improvements in blood pressure and cholesterol and increases in body weight may be plateauing,25,26 while the rising obesity epidemic may unfavorably alter trends in other metrics. Second, physical activity measures are particularly susceptible to sampling variability, so projections (particularly in women) should be treated cautiously. Third, the IMPACT CHD model evaluates CHD death, and does not consider non-fatal events such as myocardial infarction, stroke, and heart failure. These non-fatal events are potentially important targets of prevention, particularly in younger individuals. Fourth, the IMPACT CHD model is relatively simple and requires rigorous sensitivity analyses that are reflected in the wide confidence intervals. Fifth, the IMPACT CHD model does not incorporate diet, but does quantify the major downstream consequences of diet (blood pressure, cholesterol, BMI and diabetes), which are more proximal risk factors for CHD death.

Conclusions

Successfully achieving AHA 2020 CVH targets through a 20% improvement in each of six CVH metrics could prevent approximately 24% of CHD deaths expected in 2020. Similar reductions in CHD deaths may occur if current trends in these CVH metrics continue. However, unfavorable trends in some CVH metrics may lead to increased rates of adverse cardiovascular outcomes and deaths, particularly over a longer time horizon. This analysis demonstrates the utility of modelling approaches to inform health policy.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Summary.

The American Heart Association recently defined its 2020 Strategic Impact Goal of achieving a 20% reduction in cardiovascular and stroke deaths and a 20% improvement in cardiovascular health of all Americans by 2020.

Recent projections to 2020 are worrying: if current trends were to continue, cardiovascular health would improve by only 6%, and there would be approximately 480,000 coronary heart disease deaths for 2020 alone.

We used the US IMPACT Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) policy model to compare two contrasting risk factor scenarios to 2020:

assuming a 20% relative improvement in each of six metrics (smoking; cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, physical inactivity, diabetes and obesity), resulting in approximately 365,000 CHD deaths [range 327,000–403,000]), or

assuming that recent (1988–2010) trends in these metrics continue to 2020, resulting in some 335,000 CHD deaths [range 274,000–386,000]).

These estimates would represent 24% and 30% reductions in CHD death rates, respectively.

The results were predominantly driven by changes in these metrics among older Americans (in whom CHD death rates are highest and in whom total cholesterol and blood pressure trends are more favourable).

However, adverse trends in body mass index and dysglycemia among younger Americans will likely lead to adverse cardiovascular outcomes, particularly over a longer time horizon.

This analysis demonstrates the potential utility of modelling analyses to inform future US health policies. These data suggest that efforts to improve health factors in older individuals and improve health behaviors in younger individuals may maximize the number of CHD deaths prevented or postponed by 2020.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: Dr. Huffman was supported by a NHLBI-sponsored cardiovascular epidemiology and prevention training grant during part of this work (5 T32 HL069771-08).

Role of the Sponsor: All data used in this study were collected by the National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None.

References

- 1.Morbidity and Mortality: 2012 Chart Book on Cardiovascular, Lung, and Blood Diseases. Bethesda, Maryland: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, Bravata DM, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Makuc DM, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, Moy CS, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino ME, Nichol G, Paynter NP, Soliman EZ, Sorlie PD, Sotoodehnia N, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:e2–e220. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ac046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB, Critchley JA, Labarthe DR, Kottke TE, Giles WH, Capewell S. Explaining the decrease in US deaths from coronary disease, 1980–2000. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2388–2398. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa053935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ford E, Capewell S. Coronary heart disease mortality among young adults in the US from 1980 through 2002: concealed leveling of mortality rates. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:2128–2132. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heidenreich PA, Trogdon JG, Khavjou OA, Butler J, Dracup K, Ezekowitz MD, Finkelstein EA, Hong Y, Johnston SC, Khera A, Lloyd-Jones DM, Nelson SA, Nichol G, Orenstein D, Wilson PW, Woo YJ. Forecasting the future of cardiovascular disease in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:933–944. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31820a55f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, Mozaffarian D, Appel LJ, Van Horn L, Greenlund K, Daniels S, Nichol G, Tomaselli GF, Arnett DK, Fonarow GC, Ho PM, Lauer MS, Masoudi FA, Robertson RM, Roger V, Schwamm LH, Sorlie P, Yancy CW, Rosamond WD. Force obotAHASPT, Statistics Committee. Defining and Setting National Goal for Cardiovascular Health Promotion and Disease Reduction: The American Heart Association's Strategic Impact Goal Through 2020 and Beyond. Circulation. 2010;121:586–613. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ford ES, Greenlund KJ, Hong Y. Ideal cardiovascular health and mortality from all causes and diseases of the circulatory system among adults in the United States. Circulation. 2012;125:987–995. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.049122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang Q, Cogswell ME, Flanders WD, Hong Y, Zhang Z, Loustalot F, Gillespie C, Merritt R, Hu FB. Trends in cardiovascular health metrics and associations with all-cause and CVD mortality among US adults. JAMA. 2012;307:1273–1283. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dong C, Rundek T, Wright CB, Anwar Z, Elkind MS, Sacco RL. Ideal Cardiovascular Health Predicts Lower Risks of Myocardial Infarction, Stroke, and Vascular Death across Whites, Blacks and Hispanics: the Northern Manhattan Study. Circulation. 2012 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.081083. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Folsom AR, Yatsuya H, Nettleton JA, Lutsey PL, Cushman M, Rosamond WD. Community prevalence of ideal cardiovascular health, by the American Heart Association definition, and relationship with cardiovascular disease incidence. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1690–1696. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.11.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laitinen TT, Pahkala K, Magnussen CG, Viikari JS, Oikonen M, Taittonen L, Mikkila V, Jokinen E, Hutri-Kahonen N, Laitinen T, Kahonen M, Lehtimaki T, Raitakari OT, Juonala M. Ideal cardiovascular health in childhood and cardiometabolic outcomes in adulthood: the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Circulation. 2012;125:1971–1978. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.073585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huffman MD, Capewell S, Ning H, Shay CM, Ford ES, Lloyd-Jones DM. Cardiovascular health behavior and health factor changes (1988–2008) and projections to 2020: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Circulation. 2012;125:2595–2602. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.070722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Capewell S, Ford ES, Croft JB, Critchley JA, Greenlund KJ, Labarthe DR. Cardiovascular risk factor trends and potential for reducing coronary heart disease mortality in the United States of America. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:120–130. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.057885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Unal B, Critchley JA, Capewell S. Small changes in United Kingdom cardiovascular risk factors could halve coronary heart disease mortality. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:733–740. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Critchley JA, Capewell S. Substantial potential for reductions in coronary heart disease mortality in the UK through changes in risk factor levels. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57:243–247. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.4.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vartiainen E, Puska P, Pekkanen J, Tuomilehto J, Jousilahti P. Changes in risk factors explain changes in mortality from ischaemic heart disease in Finland. BMJ. 1994;309:23–27. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6946.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hunink MG, Goldman L, Tosteson AN, Mittleman MA, Goldman PA, Williams LW, Tsevat J, Weinstein MC. The recent decline in mortality from coronary heart disease, 1980–1990 The effect of secular trends in risk factors and treatment. JAMA. 1997;277:535–542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Briggs A, Sculpher M, Buxton M. Uncertainty in the economic evaluation of health care technologies: the role of sensitivity analysis. Health Econ. 1994;3:95–104. doi: 10.1002/hec.4730030206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. [Accessed 7 June 2012]; http://www.nejm.org/action/showSupplements?doi=10.1056%2FNEJMsa053935&viewType=Popup&viewClass=Suppl.

- 20.CDC Wonder. [Accessed 7 June 2012]; Available at: http://wonder.cdc.gov.

- 21.Stamler J, Stamler R, Neaton JD, Wentworth D, Daviglus ML, Garside D, Dyer AR, Liu K, Greenland P. Low risk-factor profile and long-term cardiovascular and noncardiovascular mortality and life expectancy: findings for 5 large cohorts of young adult and middle-aged men and women. JAMA. 1999;282:2012–2018. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.21.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stampfer MJ, Hu FB, Manson JE, Rimm EB, Willett WC. Primary prevention of coronary heart disease in women through diet and lifestyle. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:16–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007063430103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Capewell S, O'Flaherty M. Rapid mortality falls after risk-factor changes in populations. Lancet. 2011;378:752–753. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62302-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rose G. The Strategy of Preventive Medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307:483–490. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ford ES, Capewell S. Coronary heart disease mortality among young adults in the US from 1980 through 2002: concealed leveling of mortality rates. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:2128–2132. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.