Abstract

β-Sheets are quite frequent in protein structures and are stabilized by regular main-chain hydrogen bond patterns. Irregularities in β-sheets, named β-bulges, are distorted regions between two consecutive hydrogen bonds. They disrupt the classical alternation of side chain direction and can alter the directionality of β-strands. They are implicated in protein-protein interactions and are introduced to avoid β-strand aggregation. Five different types of β-bulges are defined. Previous studies on β-bulges were performed on a limited number of protein structures or one specific family. These studies evoked a potential conservation during evolution. In this work, we analyze the β-bulge distribution and conservation in terms of local backbone conformations and amino acid composition. Our dataset consists of 66 times more β-bulges than the last systematic study (Chan et al. Protein Science 1993, 2:1574–1590). Novel amino acid preferences are underlined and local structure conformations are highlighted by the use of a structural alphabet. We observed that β-bulges are preferably localized at the N- and C-termini of β-strands, but contrary to the earlier studies, no significant conservation of β-bulges was observed among structural homologues. Displacement of β-bulges along the sequence was also investigated by Molecular Dynamics simulations.

Keywords: beta-sheets, beta-strand, structural irregularity, evolution, structural alphabet, protein blocks, folds, structural comparison, protein structure, mining

Introduction

Protein 3D structures are often described as a succession of repetitive secondary structures1,2: (i) α-helix (or 3.613 helix) characterized by intramolecular hydrogen bonds between amino acid residues i and i + 4 and (ii) β-sheet composed of extended chains with hydrogen bonds between adjacent chains. A major difference between these two main regular secondary structures is the nonlocal nature of hydrogen bonds. In case of β-sheet, hydrogen bonding partners can be far from each other in the sequence.3 Helical structures represent 1/3rd of residues while extended structures account for 1/5th.4,5 Depending on the strand orientation, a β-sheet can be parallel, anti-parallel or mixed, resulting in different hydrogen-bonded patterns.6 The planarity of β-sheet arrangement results in a periodicity in the side-chain orientation, pointing alternatively on both sides of the sheet. The sequence specificity of β-strands and their capping regions has been widely analyzed.7,8 Prediction of β-sheets structure is difficult9–11 as β-sheet assembly is more complex than simple pair complementarities.6,12,13

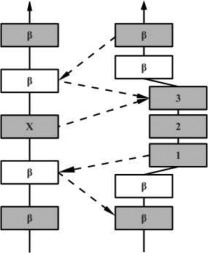

Like the helices, which are often nonlinear structures,14 the β-sheets also show irregularities, named β-bulges.15 A bulge is formed when extra residues are inserted between successive hydrogen bonds stabilizing the β-sheet, so that usually two or more residues are on one strand opposite a single residue on the other (which is named X).16,17 They are mainly observed between anti-parallel β-strands and more than two bulges per protein are found on an average.16 Richardson and coworkers were the first to analyze these conformations identifying 91 β-bulges in 28 proteins and proposed the first classification into 3 types: Classic, G1, and Wide. Milner-White analyzed the relation between G1 β-bulge and the β-hairpins describing a particular G1 β-bulge loop, related to turns.17–19 Thornton and coworker made the first systematic study of β-bulges on a nonredundant dataset. They analyzed 362 β-bulges and extended the earlier classification based on the conformation and hydrogen-bond patterns. Consequently, they introduced two new classes: the Bent and the Special β-bulges.

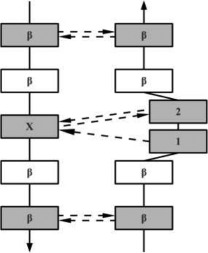

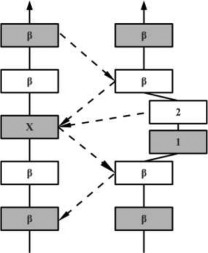

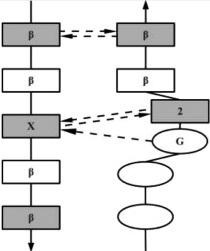

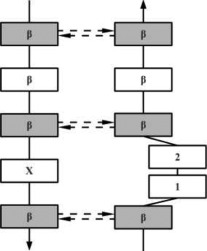

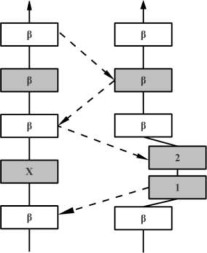

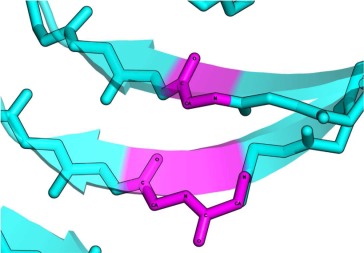

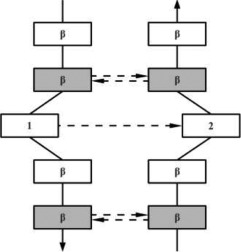

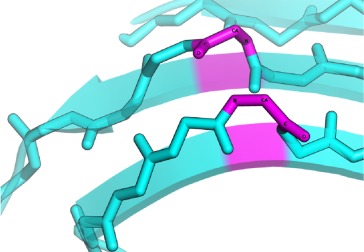

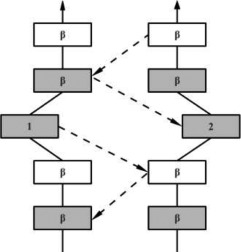

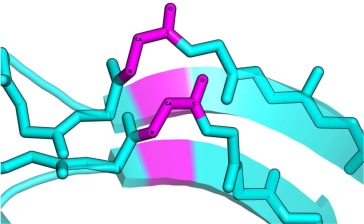

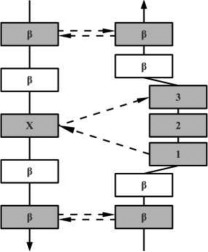

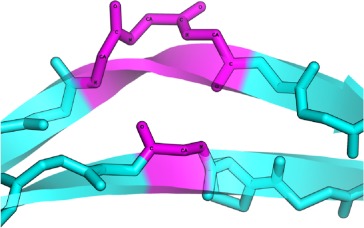

β-Bulges are thus grouped into 5 classes according to backbone conformation and hydrogen-bonding patterns (see Table I for more details): (i) the Classic β-bulge occurs between a narrow pair of hydrogen bonds; (ii) the G1 β-bulge occurs only between anti parallel β-strands; (iii) the Wide β-bulge occurs between the widely spaced pairs of hydrogen bonds; (iv) the Bent β-bulge, which do not have residue X, have the residues 1 and 2 inserted in each β-strand; and (v) the Special β-bulges that are formed when more than two residues are inserted in the bulged strand.16 The term “β-bulges residues” in the article refers to all residues which compose the β-bulges (at positions X, 1, 2, 3, and 4) unless otherwise indicated.

Table I.

β-Bulge Type Definition [Color Table can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

| β-Bulge type | Antiparallel/Parallel | Hydrogen bonding patterns | 3D conformation examples | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

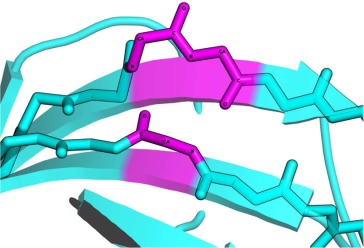

| CLASSIC | AC |  |

|

The conformation of residue 1 is nearly αR-helical. Residues 2 and X are close to the extended β conformation. All three residues have their side chains pointing in the same direction. |

| PC |  |

|

In parallel β-strands, the position 2 adopts the αR-helical conformation and position 1 and X are in β conformation. In this case, the side chains of residues 1 and 2 point to opposite directions | |

| G1 | AG |  |

|

Residue 1 is often a Glycine with dihedral angles in αL region. The hydrogen-bonding pattern is similar to that of the Classic β-bulges, except that residue 1 is always at the beginning of the β-strand (or at the end of a loop). |

| The G1 β-bulge occurs only between anti parallel β-strands. | ||||

| WIDE | AW |  |

|

Wide β-bulge occurs between the widely spaced pairs of hydrogen bonds. As the residues 1 and 2 are not involved in any main-chain bonding they can adopt many different conformations. |

| PW |  |

|

||

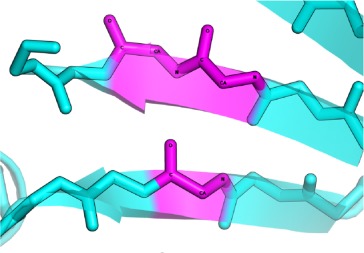

| BENT | AB |  |

|

In anti-parallel case the residues conformations are either αL − αR or αR − αL. |

| PB |  |

|

In parallel case the conformation of both residues is αR. | |

| SPECIAL | AS |  |

|

Special β-bulges are very similar to the classic type, but with more than two inserted residues in the bulged strand. |

| PS |  |

|

In the hydrogen bonding patterns diagram, directional arrows represent oriented β-strands, squares represent residues in β-strands, oval represent residues out of β-strands, and same color residues have their side chains pointing in the same direction. As all β-bulge types (except Bent) could be divided in subcategories, only the most representative hydrogen bonding pattern of the classes have been presented [See Chan, Hutchinson, Harris, and Thornton (Prot Sci, 1993), for frequencies and details on subtypes].

The extra residues do not only disrupt the normal alternation of side chain direction, but also have an effect on the directionality of β-strands; they tend to accentuate the typical right-handed twist of β-sheets. Hence, β-bulges are expected to be well conserved in proteins and a good example of this was reported for SH3 domain protein, where a β-bulge was found to be highly conserved.20

β-sheets are the least exposed and most rigid secondary structure regions.21 As β-bulges are more exposed than other strand residues, they seem to play a key role in protein-protein interaction,22 protein folding23,24 and other functions.22,25 It was also suggested that they can be associated with pathologies like neurodegenerative disorders resulted from protein aggregations26 and kidney deficiencies.27 Nonetheless, most of these studies used a limited set of protein structures or a particular family.28

The objective of this work is to study the distribution and the conservation of β-bulges in terms of types, local backbone conformation and amino acid composition, in proteins. For this purpose, we superimposed structurally similar proteins using iPBA tool. This methodology is based on the use of Protein Blocks (PBs), which is a structural alphabet composed of 16 prototypes that are 5 residues long and these prototypes were able to approximate a complete protein backbone conformation. This library of local conformations is currently the most widely used structural alphabet.29 iPBA uses the translation of protein structures as series of PBs, which can be compared using sequence alignment techniques. iPBA outperformed other established methods on a nontrivial benchmark dataset.30,31 Based on the superimposed structures, the distribution and conservation of β-bulges in terms of their types, local backbone conformation and amino acid composition were studied.

Results

Analysis of the secondary structures

About 12,132 structures, representing 2,180,241 amino-acids, were used for this study, out of 16,712 structures in the SCOP dataset filtered at 95% sequence identity. The remaining protein chains comprise structures solved by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance, involve nonstandard PDB file formats and those structures for which PROMOTIF failed to assign backbone conformations. Table II summarizes the secondary structure assignment for the SCOP95 dataset. Three structural classes that is, α/β, α + β, and all-β represent a quarter of our dataset each, while all-α represents only 16.8% of the protein chains. Secondary structure assignment resulted in 35.1% of residues in α-helical conformation, 18.5% in β-sheets and rest 46.4% in coils. Similar results were found for SCOP40 dataset, and the secondary structure distributions are in agreement with previous studies.4,32,33

Table II.

Distribution of Secondary Structures and β-Bulges in Different SCOP Classes

| Class | Prot (%) | nb res (%) | Residues | Strand nb. | β-Bulge | β-Bulge frequency | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α (%) | β (%) | Coil (%) | Prot β-bulge (%) | (%) | Per str (%) | |||||

| all − α | 16.83 | 14.45 | 61.54 | 2.50 | 35.96 | 2399 | 13.27 | 0.41 | 17.92 | 430 |

| α/β | 25.73 | 36.25 | 40.43 | 16.14 | 43.43 | 27,874 | 65.40 | 1.73 | 16.00 | 4461 |

| α + β | 22.71 | 20.63 | 33.03 | 19.26 | 47.71 | 18,557 | 85.01 | 4.14 | 33.08 | 11,597 |

| all − β | 26.12 | 21.30 | 9.51 | 34.46 | 56.03 | 33,448 | 94.92 | 7.52 | 34.67 | 711 |

| Mult. d. | 1.76 | 3.59 | 38.35 | 15.11 | 46.54 | 2717 | 92.96 | 2.75 | 26.17 | 6138 |

| Small | 4.90 | 1.64 | 14.40 | 19.36 | 66.24 | 1892 | 59.43 | 4.62 | 28.86 | 546 |

| Memb+ | 1.96 | 2.14 | 50.44 | 6.93 | 42.63 | 819 | 18.91 | 1.68 | 31.62 | 259 |

| Sum | 100.00 | 100.00 | 35.08 | 18.53 | 46.39 | 87,706 | 68.07 | 3.35 | 27.53 | 24,142 |

Are given the percentage of proteins (prot), the percentage of residues (nb res), the percentage of helical, extended and coil residues (α, β, and coil), the number of β-strands (strand nb.), the percentage of protein with at least one β-bulge (prot β-bulge), the percentage of amino acid assigned as a β-bulge, and the average number of β-bulge per strands (per str.) in each SCOP class. SCOP class mult. d. implies multi domains and memb+ correspond to membrane proteins.

β-Bulge distribution

β-Bulges represent 3.35% of the residues in the dataset (24,142 β-bulges representing 73,096 residues, see Table II). They are as recurrent as the PolyProline helix II conformation34 or the frequent types of β-turns.35 Chan and coworkers16 analyzed only 362 β-bulges from 170 proteins. In this work, the dataset used is 66 times bigger, nevertheless a similar distribution of β-bulges was found (see Supporting Information Table S1). Antiparallel β-bulges represent 92.3% of all β-bulges; parallel ones being less frequent (7.7%). On an average, each protein has two β-bulges, while the average occurrence reaches three for the all-β proteins.

As expected, the average number of β-bulges per protein is proportional to the length and the number of β-strands. More than 90.1% of β-bulges were found in structures, which are shorter than 400 residues and having at least 3 β-strands.

Classic β-bulges are the majority with a frequency of 57.0%, followed by G1 β-bulges (32.8%), the other three types being rarer (Wide β-bulges: 4.9%, Special β-bulges: 3.3% and Bent β-bulges: 1.9%). A significant change compared to the previous study,16 is an increase in the frequency of antiparallel classic β-bulges from 46.7 to 52.6% and a decrease in antiparallel Wide β-bulges, from 8.3 to 3.7%.

PROMOTIF assigns β-bulges according to their conformation and hydrogen-bonding patterns. Hence, these characteristics could also apply to residues localized in a loop, as noticed for G1 β-bulge loop.17 β-bulges are observed with residues completely localized inside β-sheets, partly outside or completely outside the sheet.

As shown in Table III only 54.3% of β-bulges are composed entirely of residues localized inside the β-strands. The rest is mainly represented by antiparallel G1 β-bulges with 98.1% having at least one residue localized outside β-strands, which often corresponds to G1 β-bulge loop.17

Table III.

β-Bulge Types

| Type | Observed | Position | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In (%) | In and Out (%) | Out (%) | ||

| A B | 153 | 100.00 | – | – |

| P S | 194 | 90.21 | 9.79 | – |

| P W | 285 | 97.19 | 2.81 | – |

| P B | 312 | 95.83 | 4.17 | – |

| A S | 615 | 96.42 | 3.58 | – |

| A W | 905 | 99.89 | 0.11 | – |

| P C | 1060 | 100.00 | – | – |

| A G | 7914 | 1.91 | 53.74 | 44.35 |

| A C | 12704 | 74.72 | 22.83 | 2.45 |

| Sum | 24142 | 54.28 | 29.89 | 15.83 |

Given the observed distribution in the dataset of bent (B), special (S), wide (W), G1 (G), and classic (C) β-bulges, which are in parallel (P) or antiparallel β-sheets (A). The corresponding frequencies of β-bulges, which are composed of residues localized completely in β-strands (In), that do not lie in β-strands (Out) or localized partly in strands (In and Out), are highlighted.

β-Bulges are usually localized close to β-strand extremities, that is, 90% of β-bulges are within 3 residues of a β-strand extremity (see Supporting Information Table S2). If we consider the β-bulges that are composed of residues lying exclusively in β-strands, the bulge residues are rarely localized in the middle of β-strands; this behavior can be observed for all types of β-bulges (see Supporting Information Fig. S1). β-Bulge residues (75.35%) are localized either within a strand or between two consecutive strands (see Supporting Information Table S3).

β-Bulge in SCOP classes

As seen in Tables 2 and Supporting Information S4, the distribution of β-bulges is not similar in all SCOP classes. β-Bulges were even found in the all-α class which by definition has a low β-sheet content. About 30.7% of these β-bulges are entirely found inside β-sheets and are mainly antiparallel G1 β-bulges (54.9%). As α/β class is mainly composed of parallel β-sheets, it is expected to have the highest content of parallel Special, Wide, Bent, and Classic β-bulges (3.4, 5.0, 2.9, and 20.2%, respectively). α + β and all-β classes exhibit roughly the same behavior with the dominance of antiparallel Classic β-bulges (60.5 and 55.2%, respectively), a significant representation of antiparallel G1 β-bulges (31.0 and 35.0%, respectively) and a limited number of β-bulges outside β-strand (∼15%), like α/β class.

The multidomain protein and small protein classes have similar distributions with ∼30% of β-bulges in β-strands, 30% outside β-strands and 38% are partly in β-strands. The membrane associated class has lower number of β-bulges, but has the highest number of antiparallel Wide β-bulge (9.3%, which is twice the frequency in the other classes); the other 5 types of β-bulges were never observed.

Amino-acid preferences of β-bulge

Table IV shows the amino acid and the Protein Block preferences of the different β-bulges (see Supporting Information Table S5). Aspartate is found over-represented, mainly at positions 1 and 2. For all β-bulge types, a significant preference for the amino acids Glycine, Asparagine, and Proline is seen. Fewer amino acid preferences were found in all parallel β-bulges, and in antiparallel Bent β-bulges.

Table IV.

Amino Acid and Protein Block Preferences for β-Bulges

| Amino acid preferences | Protein block preferences | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-Bulge type | % | X | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | X | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| A B | 0.63 | D, N | D, G, N | b, i | b, i | ||||||

| P B | 1.34 | D, G, N | D, N | b, i | b, i | ||||||

| A C | 52.59 | I, L, R, V, W | D, I, K, L | A, D, E, G, H, K, R, S | d, h | a, b | c, d, g, j | ||||

| P C | 4.46 | V | I, V | K | c | a, f, g | b, i | ||||

| A S | 2.52 | G, N, P | G, P, S | D, E, G, N, P | D, E, G, N, P | D, E, G, N, P | b, i | b, f, h, j | b, i, k | b, i, k | b, i, k |

| P S | 0.82 | D, P | D, K, N | P | P | P | b | e, f, g | b, h, k | b, h, k | b, h, k |

| A W | 3.75 | G, N, S, T, W | D, E, G, N, P | D, G, N, P | b, d | b, h, i, j | a, b, i | ||||

| P W | 1.21 | --- | T | D, E, G | b, i | b, h | b, d, g, i, j | ||||

| A G | 32.66 | C, D, N | D, G, N | D, E, K, N, Q, R, S, T | f | i, p | a | ||||

| 100.00 | |||||||||||

For each β-bulge type and for all β-bulge residue positions (X, 1, 2, 3, and 4), the over-represented amino acid and protein block are specified. The data has been normalized with respect to the amino acid and protein block frequencies in the β-sheets. These over-represented amino acids and PBs correspond to positive Z-scores greater than the threshold value of 4.42. The hatched cases correspond to undefined residue positions. The bold and underlined labels indicate new preferences compared to the previous study (Chan et al., 1993).

Previous work on β-bulges mainly focuses on three β-bulge types, that is, antiparallel Classic, G1, and antiparallel Wide [see Tables 6 of Chan's study16]. About 85, 69 and 30 times more β-bulges of each type are identified in this work leading to a new characterization (see bold and underlined labels in Table IV). For the antiparallel Classic β-bulge, four new over-represented residues are observed, Leucine at position X, Asparagine and Lysine at position 1 and Arginine at position 2. However, three over-represented residues reported earlier, had lesser preference in this study, Tyrosine at position X and Valine, Glutamate, and Serine at position 1 (see Supporting Information Table S5). In the case of antiparallel G1 β-bulges, striking differences observed were (a) lesser preferences for Histidine and Serine at position X, (b) over-representation of Aspartate at position 1 and (c) enrichment of three residues at position 2, that is, Serine, Threonine, and Asparagine, which are otherwise common in all β-bulge types.

Table VI.

Influence of the sequence and structural homology of structures

| (%) | Full superimposition | Partial superimposition | No superimposition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence identity ≤ 35% | 25.67 | 12.81 | 61.52 |

| Same type β-bulges | 24.67 | 7.49 | |

| Different type β-bulges | 1.00 | 5.32 | |

| Sequence identity > 35% | 67.33 | 8.65 | 24.02 |

| Same type β-bulges | 66.06 | 5.13 | |

| Different type β-bulges | 1.27 | 3.52 | |

| GDT_TS [15,40] | 15.84 | 13.97 | 70.19 |

| Same type β-bulges | 15.00 | 8.30 | |

| Different type β-bulges | 0.84 | 5.67 | |

| GDT_TS [40,100] | 53.42 | 9.87 | 36.71 |

| Same type β-bulges | 52.05 | 5.36 | |

| Different type β-bulges | 1.37 | 4.52 |

The frequencies of β-bulge superimpositions (Full, Partial, and No superimposition) for two sequence identities ranges, and two ranges of GDT_TS are given. These frequencies represent the influence of the sequence homology, and structural homology on the β-bulge conservation. Details on β-bulges type conservation are also given for each value.

Finally, the antiparallel Wide β-bulges showed preference for Glycine and Asparagine at positions X and 1, and Serine and Tryptophan at position X. Position 2 had two new over-represented amino acids, namely Glycine and Proline, apart from Aspartate and Asparagine. Another major difference is the absence of preference for Glutamine.

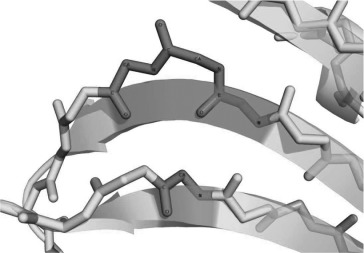

Local conformation preferences of β-bulge

We also investigated the preference for local backbone conformations associated with β-bulges. Protein Blocks is currently the most widely used structural alphabet.29 It gives a finer description of local backbone conformations when compared with the classical secondary structures.36 PBs b and i, are found strongly over-represented (21 and 14 fold each) in β-bulges. PB b is found at the N-cap of β-strands and i is frequent in loop region.37 These two PBs are found in successive positions and strongly mark the irregularity in the β-strand. These PB conformations are not easily altered, as seen in the PB substitution matrix developed in our earlier work.30,31 Interestingly, both parallel (minority) and antiparallel (majority) types favored similar Protein Blocks are found overrepresented for both antiparallel (majority) and parallel (minority) types. Residue X is mainly in β-strand conformation reflected by the preferences for PB d, which correspond to the central region of classical β-strand, PBs b and c corresponding to the N cap, and PB f to the C-cap. In our previous studies, we have shown that certain preferential transitions are observed between PBs,36,37 that is, PBs (letters) have preferred successions (words). In G1 β-bulge PBs i or p, at position 1, are seen to be followed by PB a, at position 2.

Antiparallel Classic β-bulges were characterized by distinct preferences for amino acids. They also have distinct PBs' patterns with PBs d or h favored at position X. PB h is mainly associated with residues following the end of a β-strand while PB a at position 1 and PBs g and j at position 2 are mainly loop associated PBs. AC β-bulges are mainly found within β-strands (∼75% see Table III) with a preference to strand termini, an assignment in agreement with the observed PBs, mainly associated to loops.

Protein superimpositions

Analysis of β-bulges in specific protein families, for example, the WD40 family28 and the immunoglobulin family,16 has suggested that β-bulges could be more conserved than other parts of protein structures. About 950,793 structure superimpositions were carried out using iPBA program. Proteins placed together in the same fold category may not have a common evolutionary origin: the structural similarities could just arise from the physico-chemical properties of proteins favoring certain packing arrangements and chain topologies. The average GDT_TS score is 33.25 with a peak at 31 (see Supporting Information Fig. S2). Even though superimpositions were performed at the level of SCOP fold, a non negligible proportion of structural alignments shares a very low GDT_TS, that is, some structures, classified in same SCOP fold cannot be properly superimposed. Hence, we selected only superimpositions with GDT_TS score better than 15, a threshold already used in a previous study38; corresponding to an average RMSD lower than 2.69Å (see Supporting Information Fig. S3), reflecting superimpositions of structures sharing similar global conformation. Consequently, 716,346 superimpositions were selected.

Similarly, a strong correlation exists between GDT_TS and sequence identity, as seen between GDT_TS and RMSD (see Supporting Information Fig. S3). The GDT_TS and the sequence identity have an exponential correlation. As the sequence is less conserved than the structures, we observed that a GDT_TS score of 60 corresponds to a sequence identity of about 35% on an average. We observed 1,665,200 non-superimposed β-bulges and 531,567 aligned β-bulges (full and partial). As certain folds contained more experimental protein structures, the distribution of β-bulges was normalized.

Are the β-bulges conserved among homologous structures?

On an average, a β-bulge has 42% chances of being conserved (superimposed: 30% fully and 12% partially). In majority of the cases, the two β-bulges superimposed share the same type and secondary structure localization. A β-bulge has 33.0% probability to be conserved with the same type, 31.4% with the same secondary structure localization, and 27.4% with both (see Table V). Conservation of β-bulge with change of types (9%) was observed five times more for partial than for full superimposition (probability of 7.5 and 1.5%, respectively). This result emphasizes that changes in the hydrogen bond pattern of β-bulge goes hand in hand with modification of the local structural conformation. It must be noticed that it often changed the β-bulge type and the superimposition in such case can only be partial.

Table V.

Conservation of β-Bulge Type and Localization of Superimposed β-Bulges

| (%) | Different β-sheet localization | Same β-sheet localization | Sum |

|---|---|---|---|

| Superimposition of different type β-bulges | 4.97 | 4.01 | 8.98 |

| Superimposition of same type β-bulges | 5.62 | 27.40 | 33.03 |

| Sum | 10.59 | 31.41 | 42.00 |

| No superimposition | – | – | 58.00 |

The frequencies of β-bulge superimpositions corresponding to the case of conservation of β-bulge type and conservation of β-sheet localization (In, Out, and In and Out), are given.

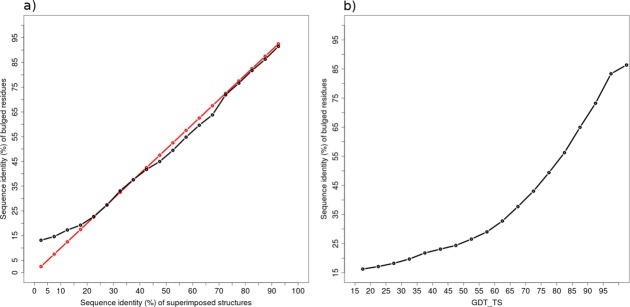

In the following sections, the residues, which form the bulge (positions 1–4), are named the bulged residues. A β-bulge has only 13.2% probability to be structurally conserved with the same X-residue, and only 5.1% chance with same bulged residues. For different β-bulge types (except Bent) at equivalent positions, the probabilities to be structurally conserved with the same X-residue decreases to 0.71%, and down to 0.11% for the same bulged residues. Hence, the amino acid composition of a conserved β-bulge in homologous structures is not necessarily similar. However, conserved β-bulges with same bulged amino acid sequence have 91% probability to share the same β-bulge type. Figure 1(a) shows the conservation of bulged residues in regards to the whole sequence. It highlights without any doubt that the β-bulges are not more conserved (on average) than any other regions of the proteins. As expected [Fig. 1(b)], sequence identity variation is correlated with GDT_TS, underlining no specific generic constraints specific to β-bulge. This result is not in contradiction with specific studies that underline the conservation of β-bulge, as we see better structural conservation of β-bulge for alignments with higher GDT_TS score and a higher sequence identity. The probability to observe a conserved β-bulge in homologous structures increases from 38.48% (for sequence identity lower than 35%) to 75.98% (for higher rate), and from 29.81% (for GDT_TS between 15 and 40) to 63.29% (for higher GDT_TS, see Table VI).

Figure 1.

Conservation of bulged residues. The average sequence identity of non-X residues of superimposed β-bulges with respect to (a) sequence identity of superimposed structures (black line), the red line represents the reference line f(x) = x, and (b) GDT_TS of structural alignments. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Stability of β-bulges

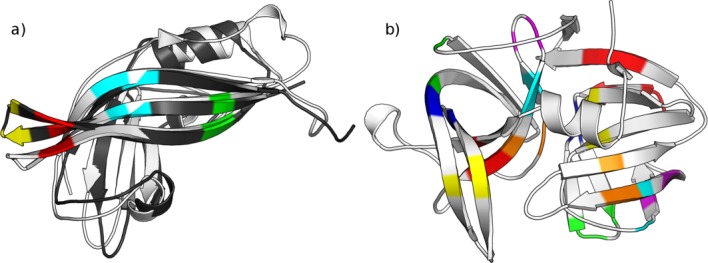

To understand the structural significance and stability of β-bulges, we studied a particular case of α-lytic protease (PDB code 1SSX39) using Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations. This protein is 198 residues long and is characterized by a large number of about 15 β-bulges [see Fig. 2(b)]. Three different temperatures were applied during the MD simulations to analyze the stability of β-bulges. Thirty-four different β-bulges have been observed in the different simulations (see Supporting Information Table S6). The 15 β-bulges remain stable and are present at least 90% of the times for the three temperatures. Nonetheless, formation and disappearance of β-bulges (see Supporting Information Fig. S4) and changes in their types were observed. It is mainly due to significant local conformational changes that lead to the loss or gain of hydrogen bonds. Some β-bulges were quite transient (seen <29% of the simulation time) at all temperatures. These transient β-bulges are mainly composed of residues, which are also observed in stable β-bulges. This could be due to the local structural environment that alters the protein flexibility resulting in the β-bulge shift. For example, the two β-bulges found at position 44–51-52 and 45–50-51 correspond to a stable and transient β-bulge respectively, with overlapping positions in the sequence. Interestingly, these putative displacements are accompanied by a change of β-bulge type.

Figure 2.

Stability of β-bulges. (a) The two SCOP domains d1es6a1 (in white) and d1h2ca_ (in black) of Ebola virus matrix protein share identical sequence and similar 3D structure (GDT_TS = 46.62 and RMSD = 2.06Å). However, they exemplify variable number of β-bulges (3 for d1es6a1 and 4 for d1h2ca_). Three β-bulges are conserved between these homologous structures (two partial superimpositions in red and blue, and one full superimposition in green) and one β-bulge is missing in d1es6a1 (in yellow). This observation highlights the possible effect of protein flexibility or crystal packing on β-bulges formation. (b) The α-lytic protease (1SSX), 198 residues long, is characterized by a large number of β-bulges (15 in number) compared to its length. This structure was used in three molecular dynamic simulations (at temperatures 298, 310, and 353 K) to study the stability of β-bulges (see Figure S4 and Supporting Information Table S6). [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Discussion

This study is based on the analysis of a larger dataset of β-bulges compared to previous works. We provide a new description of amino acid preferences [see Table IV and Supporting Information Table S5(a)] associated with β-bulges. Various studies on specific protein families have shown the importance of conserved β-bulges.40–42 Higher conservation of β-bulges was observed with the increasing degree of homology in terms of both sequence and structure.

However, our results highlight the observation that β-bulges in structurally similar proteins are not necessarily conserved. We found that a β-bulge has only 42% probability to be conserved in structures sharing the same fold. We also showed that different types of β-bulges are conserved among similar structures and transition between β-bulge types is more frequent than expected (around 1 in 10 β-bulges). Nonetheless, we do not observe any significant preferences for certain type to be conserved [see Fig. 1(a) and Supporting Information Table S7]. For instance, different numbers of β-bulges were observed in two structures corresponding to the matrix protein VP40 of Ebola virus43,44 [see Fig. 2(a)]. These structures (SCOP domain: d1es6a1 and d1h2ca_) share the same amino acid sequence and are very close in terms of global conformation (GDT_TS = 46.62 and RMSD = 2.06 Å). 3 β-bulges were found conserved between both structures and one was missing in one structure [see Fig. 2(a)]. This observation highlights the possible effects of protein flexibility or crystal packing on β-bulges formation.

Finally, this work highlights that the conservation of β-bulges is not significantly influenced by conservation of the fold, contrary to the speculations in previous studies. However higher is the homology in terms of sequence and structure, higher is the probability to find conserved β-bulges. Molecular dynamic studies on bulged protein allow the observation of stable and transient nature of β-bulges. This behavior needs to be investigated at a greater detail on related proteins to quantify its impact on conservation studies.

Materials and Methods

Overview of the method

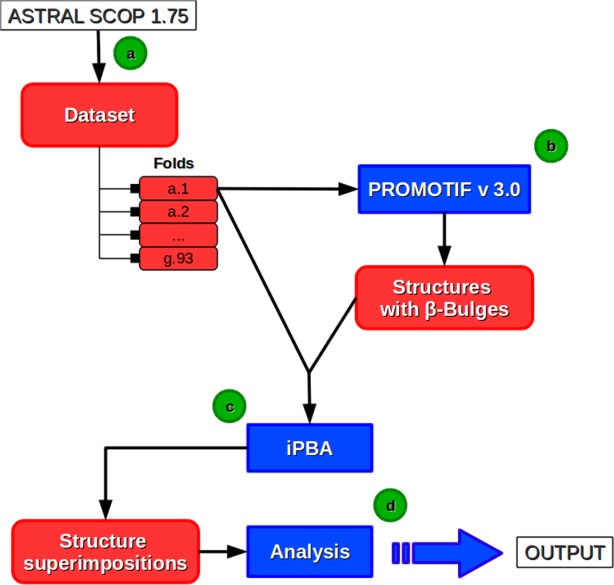

Figure 3 shows the workflow for the analysis of β-bulges. Protein structures were taken from the ASTRAL SCOP dataset45 [Fig. 3(a)]. Secondary structures, including β-bulges were assigned by PROMOTIF software46 [Fig. 3(b)]. Protein structural domains containing at least one β-bulge were superimposed with protein structural domains belonging to the same SCOP folds. Pairwise structural alignments were performed using iPBA30 [Fig. 3(c)]. The conservation of β-bulges at structurally equivalent positions were then analyzed [Fig. 3(d)].

Figure 3.

Principle of the analysis of β-bulges. (a) Protein structures are taken from the ASTRAL SCOP dataset.45 (b) Classical secondary structures and β-bulges are assigned with PROMOTIF software.46 All the protein structures containing at least one β-bulge and belonging to same SCOP fold are superimposed, using (c) iPBA software(30–31), and then (d) the selected β-bulges superimpositions are analyzed. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Structural datasets

Two sets of protein structures were extracted from Protein Data Bank47 based on the ASTRAL SCOP dataset,45 filtered at 40% and 95% sequence identity. The proteins were classified into folds and classes based on the SCOP classification.48 All NMR structures were excluded from the analysis. SCOP95 dataset contained 16,712 structures representing 1,195 folds and 7 classes.

Analysis of local backbone conformation

Secondary structures have been assigned using PROMOTIF software46; it is based on DSSP methodology49 and used backbone hydrogen bond patterns. PROMOTIF also gives assignments of different types of turns and β-bulges. The assignment of β-bulges is based on Chan et al. classification16 that defines five main types Classic (C), Bent (B), Wide (W), G1, and Special (S). PROMOTIF is used for the secondary structure assignment in PDBsum50 and it is the only currently available software that allows distinguishing and assigning the different types of β-bulges.

Protein Blocks (PBs)37 were also used to have a finer and different view of the local backbone conformation. They correspond to a set of 16 pentapeptide conformations, labeled from a to p, described as a series of (φ,ψ) dihedral angles29,51 (see Supporting Information Table S8). This library was obtained by clustering all pentapeptide conformations using an unsupervised classifier similar to Kohonen Maps52,53 and Hidden Markov Models.54 The PBs m and d can be roughly described as prototypes for the central region of α-helix and β-strand, respectively. PBs a, b, and c primarily represent the N-cap of β -strand while e and f correspond to C-caps. PBs g to j are specific to coils. k and l correspond to N cap of α-helix while PBs n to p are associated with C-caps. This structural alphabet of 16 prototypes allows a reasonable approximation of local protein 3D structures37 with an average root mean square deviation (RMSD) of about 0.42 Å.36

Structure superimposition

Abstraction of structures in terms of PBs helps to encode 3D information into a 1D sequence.29,37,51 We used classical amino acid sequence alignment strategies to align PBs sequences used to compare protein structures.55–,57 The alignment approach was refined with the use of an anchor-based dynamic programming algorithm, which first identifies all high scoring and structurally favorable local alignments (anchors). The segments between these anchors are then aligned to obtain a global alignment. This improved PB based structure alignment approach, namely iPBA, outperformed other established methods as seen with different robust benchmark datasets.30,31 ProFit (version 3.1)58 is used to obtain the final 3D superimposition of two protein structures (based on the PB-based sequence alignment). ProFit performs least squares fit of protein structures based on the residue equivalences in a given sequence alignment. Only Cα atoms of equivalent residues were used for the calculations.

iPBA provides two measures of the structural superimposition: the RMSD, and the global distance test total score (GDT_TS defined by Zemla in 200359). This latter varying between 0 and 100, and reflects the global similarity of two protein structures. It was used for model assessment in the last rounds of critical assessment of techniques for protein structure prediction60.

Sequence alignment

Amino acid sequence alignment was performed using CLUSTAL-W (version 2.1).61 Default parameters were used with Gonnet substitution matrix.62

Characterization of β-bulge superimposition

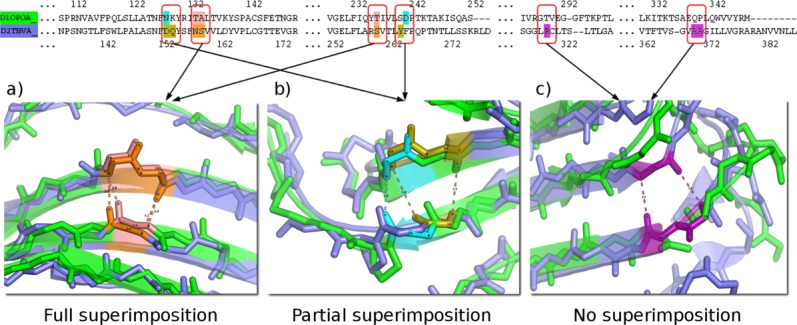

Proteins classified into the same fold were superimposed with iPBA. The structure based sequence alignment generated by iPBA was used to evaluate the structural conservation of β-bulges. Based on this alignment output, we can distinguish three cases of β-bulges superimposition (Fig. 4):

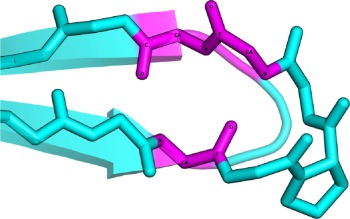

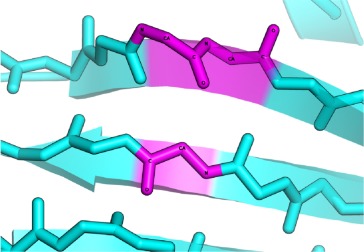

Figure 4.

The three possible cases of β-bulge structure superimposition. The superimposition of carnation Mottle virus capsid protein chain A (PDB code 1OPO72) and coat protein of tomato bushy stunt virus chain A (PDB code 2TBV73). Structure comparison results in a GDT_TS score of 64.0, (RMSD equals to 1.72Å and 26.6% sequence identity). Each protein had six β-bulges including four, which are structurally equivalent. It exhibits three possible cases: (a) Full superimposition: all residues in β-bulges are found to be perfectly aligned, for example, for the Classic β-bulge of (pink color) carnation mottle virus capsid protein at residue Thr-236 (residue-X), Thr-133 and Ala-134, and coat protein of tomato bushy stunt virus (orange color) with residues Ser-260 (residue-X), Asn-158, and Ser-159; (b) Partial Superimposition: only some of the residues composing β-bulges are aligned, for example, the Bent β-bulge of 1OPO (in blue), composed by residues Asn-128 and Asp-241, with the Classic β-bulge of 2TBV (in gold), composed by residues Tyr-264 (residue-X), Asp-153, and Gln-154. Only 2 residues are aligned with each other, and (c) No superimposition: β-bulge residues found in one protein structure but not aligned with β-bulge residues on the second one, for example, the Classic β-bulge of 2TBV (in purple), composed of residues Arg-319 (residue-X), Ala 370 and Ala 371, have no direct counterparts. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Full Superimposition: All the residues of first β-bulge are aligned with those in the second β-bulge. [see Fig. 4(a)], the number of aligned residues correspond to the number of residues of the shorter β-bulge.

Partial Superimposition: only some residues of the smaller β-bulge are aligned with the residues of the other β-bulge [see Fig. 4(b)].

Non Superimposed β-bulges: A β-bulge found in one protein structure is not aligned with a β-bulge on the other protein [see Fig. 4(c)].

Amino acid and PB composition

Occurrence of each amino acid and Protein Block in a particular β bulge type, have been normalized into a Z-score:

with the observed occurrence number of amino acid or PB i in position j (residue position X, 1, 2, 3, or 4) for a given particular β-bulge type and

the observed occurrence number of amino acid or PB i in position j (residue position X, 1, 2, 3, or 4) for a given particular β-bulge type and , the expected number. The expected values correspond to the product of the occurrence in position j and the frequency of amino acid i in the entire databank (or from β-strands of the databank). Positive Z-scores correspond to over-represented amino acids or PBs, and the threshold values of 4.42 and 1.96 were chosen to indicate the level of significance (P-value <10−5 and 5.10−2, respectively). This measure was used in our previous studies to analyze the amino acid representation in Protein Blocks.37,63

, the expected number. The expected values correspond to the product of the occurrence in position j and the frequency of amino acid i in the entire databank (or from β-strands of the databank). Positive Z-scores correspond to over-represented amino acids or PBs, and the threshold values of 4.42 and 1.96 were chosen to indicate the level of significance (P-value <10−5 and 5.10−2, respectively). This measure was used in our previous studies to analyze the amino acid representation in Protein Blocks.37,63

Molecular simulations

MD simulations were performed with GROMACS 4.5.464–67 using Amber 03 force field68 for proteins and the explicit TIP3P solvent model for water molecules was used.69 The structure was immersed in a water box with periodic boundary conditions and neutralized with Na+ or Cl− counterions. The energy of each system was then minimized with a steepest-descent algorithm for 2000 steps. MD simulation was performed in NPT ensemble, with temperature and pressure kept constant, at three different temperatures (298, 310, and 353 K) and 1 bar pressure using Berendsen algorithm.67 The coupling time constants were τ = 0.1 ps and τ = 4 ps for temperature and pressure, respectively. Bond lengths were constrained with the LINCS algorithm,70 which allowed an integration step of 2fs. The Particle-mesh Ewald summation71 was used to handle long-range electrostatic interactions using a cut-off of 1.4 nm for nonbonded interactions. An equilibration step was first performed for 500 ps, with protein atom positions constrained while ions and water molecules were free to move, followed by an unrestrained production step of 50 ns. The coordinates were recorded at every 10 ps interval. The MD simulation was checked and analyzed using Gromacs tools.

Glossary

- AB

antiparallel bent

- AC

antiparallel classic

- AG

anti-parallel G1

- AS

antiparallel special

- ASTRAL

database for sequence and analysis

- AW

antiparallel wide

- DSSP

database of secondary structure assignment

- GDT_TS

global distance test total score

- iPBA

improved protein block alignment

- LINCS

LINear constraint solver

- MD

molecular dynamic

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- PB

parallel bent

- PB(s)

protein block(s)

- PC

parallel classic

- PW

parallel wide

- PS

parallel special

- RMSD

root mean square deviation

- SCOP

structural classification of proteins.

Supplementary material

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Eisenberg D. The discovery of the alpha-helix and beta-sheet, the principal structural features of proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:11207–11210. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2034522100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pauling L, Corey RB, Branson HR. The structure of proteins; two hydrogen-bonded helical configurations of the polypeptide chain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1951;37:205–211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.37.4.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pauling L, Corey RB. The pleated sheet, a new layer configuration of polypeptide chains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1951;37:251–256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.37.5.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tyagi M, Bornot A, Offmann B, de Brevern AG. Analysis of loop boundaries using different local structure assignment methods. Protein Sci. 2009;18:1869–1881. doi: 10.1002/pro.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fourrier L, Benros C, de Brevern AG. Use of a structural alphabet for analysis of short loops connecting repetitive structures. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5:58. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Penel S, Morrison RG, Dobson PD, Mortishire-Smith RJ, Doig AJ. Length preferences and periodicity in beta-strands. Antiparallel edge beta-sheets are more likely to finish in non-hydrogen bonded rings. Protein Eng. 2003;16:957–961. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzg147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Regan L. Protein structure. Born to be beta. Curr Biol. 1994;4:656–658. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00147-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colloc'h N, Cohen FE. Beta-breakers: an aperiodic secondary structure. J Mol Biol. 1991;221:603–613. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)80075-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wouters MA, Curmi PM. An analysis of side chain interactions and pair correlations within antiparallel beta-sheets: the differences between backbone hydrogen-bonded and non-hydrogen-bonded residue pairs. Proteins. 1995;22:119–131. doi: 10.1002/prot.340220205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hutchinson EG, Sessions RB, Thornton JM, Woolfson DN. Determinants of strand register in antiparallel beta-sheets of proteins. Protein Sci. 1998;7:2287–2300. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560071106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujiwara K, Toda H, Ikeguchi M. Dependence of alpha-helical and beta-sheet amino acid propensities on the overall protein fold type. BMC Struct Biol. 2012;12:18. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-12-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mandel-Gutfreund Y, Zaremba SM, Gregoret LM. Contributions of residue pairing to beta-sheet formation: conservation and covariation of amino acid residue pairs on antiparallel beta-strands. J Mol Biol. 2001;305:1145–1159. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ho BK, Curmi PM. Twist and shear in beta-sheets and beta-ribbons. J Mol Biol. 2002;317:291–308. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar S, Bansal M. Geometrical and sequence characteristics of alpha-helices in globular proteins. Biophys J. 1998;75:1935–1944. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77634-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richardson JS, Getzoff ED, Richardson DC. The beta bulge: a common small unit of nonrepetitive protein structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978;75:2574–2578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.6.2574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan AW, Hutchinson EG, Harris D, Thornton JM. Identification, classification, and analysis of beta-bulges in proteins. Protein Sci. 1993;2:1574–1590. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560021004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milner-White EJ. Beta-bulges within loops as recurring features of protein structure. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1987;911:261–265. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(87)90017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leader DP, Milner-White EJ. Motivated proteins: a web application for studying small three-dimensional protein motifs. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.James Milner-White E, Poet R. Loops, bulges, turns and hairpins in proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1987;12:189–192. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larson SM, Davidson AR. The identification of conserved interactions within the SH3 domain by alignment of sequences and structures. Protein Sci. 2000;9:2170–2180. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.11.2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bornot A, Etchebest C, de Brevern AG. Predicting protein flexibility through the prediction of local structures. Proteins. 2011;79:839–852. doi: 10.1002/prot.22922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richardson JS, Richardson DC. Natural beta-sheet proteins use negative design to avoid edge-to-edge aggregation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:2754–2759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052706099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Capraro DT, Roy M, Onuchic JN, Gosavi S, Jennings PA. beta-Bulge triggers route-switching on the functional landscape of interleukin-1beta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:1490–1493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114430109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao L, Ericksen B, Wu X, Zhan C, Yuan W, Li X, Pazgier M, Lu W. Invariant gly residue is important for alpha-defensin folding, dimerization, and function: a case study of the human neutrophil alpha-defensin HNP1. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:18900–18912. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.355255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Axe DD, Foster NW, Fersht AR. An irregular beta-bulge common to a group of bacterial RNases is an important determinant of stability and function in barnase. J Mol Biol. 1999;286:1471–1485. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siepen JA, Radford SE, Westhead DR. Beta edge strands in protein structure prediction and aggregation. Protein Sci. 2003;12:2348–2359. doi: 10.1110/ps.03234503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Azinas S, Colombo M, Barbiroli A, Santambrogio C, Giorgetti S, Raimondi S, Bonomi F, Grandori R, Bellotti V, Ricagno S, Bolognesi M. D-strand perturbation and amyloid propensity in beta-2 microglobulin. FEBS J. 2011;278:2349–2358. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu XH, Wang Y, Zhuo Z, Jiang F, Wu YD. Identifying the Hotspots on the Top Faces of WD40-Repeat Proteins from Their Primary Sequences by beta-Bulges and DHSW Tetrads. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43005. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joseph AP, Agarwal G, Mahajan S, Gelly J-C, Swapna LS, Offmann B, Cadet F, Bornot A, Tyagi M, Valadié H, Schneider B, Cadet F, Srinivasan N, de Brevern AG. A short survey on Protein Blocks. Biophys Rev. 2010;2:137–145. doi: 10.1007/s12551-010-0036-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joseph AP, Srinivasan N, de Brevern AG. Improvement of protein structure comparison using a structural alphabet. Biochimie. 2011;93:1434–1445. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gelly JC, Joseph AP, Srinivasan N, de Brevern AG. iPBA: a tool for protein structure comparison using sequence alignment strategies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W18–23. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colloc'h N, Etchebest C, Thoreau E, Henrissat B, Mornon JP. Comparison of three algorithms for the assignment of secondary structure in proteins: the advantages of a consensus assignment. Protein Eng. 1993;6:377–382. doi: 10.1093/protein/6.4.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin J, Letellier G, Marin A, Taly J-F, de Brevern AG, Gibrat J-F. Protein secondary structure assignment revisited: a detailed analysis of different assignment methods. BMC Struct Biol. 2005;5:17. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-5-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mansiaux Y, Joseph AP, Gelly JC, de Brevern AG. Assignment of PolyProline II conformation and analysis of sequence-structure relationship. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18401. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bornot A, de Brevern AG. Protein beta-turn assignments. Bioinformation. 2006;1:153–155. doi: 10.6026/97320630001153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Brevern AG. New assessment of a structural alphabet. In Silico Biol. 2005;5:283–289. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Brevern AG, Etchebest C, Hazout S. Bayesian probabilistic approach for predicting backbone structures in terms of protein blocks. Proteins. 2000;41:271–287. doi: 10.1002/1097-0134(20001115)41:3<271::aid-prot10>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Joseph AP, Srinivasan N, de Brevern AG. Cis-trans peptide variations in structurally similar proteins. Amino Acids. 2012;43:1369–1381. doi: 10.1007/s00726-011-1211-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fuhrmann CN, Kelch BA, Ota N, Agard DA. The 0.83 A resolution crystal structure of alpha-lytic protease reveals the detailed structure of the active site and identifies a source of conformational strain. J Mol Biol. 2004;338:999–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim CW, Michaels ML, Miller JH. Amino acid substitution analysis of E. coli thymidylate synthase: the study of a highly conserved region at the N-terminus. Proteins. 1992;13:352–363. doi: 10.1002/prot.340130407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dion-Schultz A, Howell EE. Effects of insertions and deletions in a beta-bulge region of Escherichia coli dihydrofolate reductase. Protein Eng. 1997;10:263–272. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.3.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen PY, Gopalacushina BG, Yang CC, Chan SI, Evans PA. The role of a beta-bulge in the folding of the beta-hairpin structure in ubiquitin. Protein Sci. 2001;10:2063–2074. doi: 10.1110/ps.07101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dessen A, Volchkov V, Dolnik O, Klenk HD, Weissenhorn W. Crystal structure of the matrix protein VP40 from Ebola virus. EMBO J. 2000;19:4228–4236. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.16.4228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gomis-Ruth FX, Dessen A, Timmins J, Bracher A, Kolesnikowa L, Becker S, Klenk HD, Weissenhorn W. The matrix protein VP40 from Ebola virus octamerizes into pore-like structures with specific RNA binding properties. Structure. 2003;11:423–433. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(03)00050-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chandonia JM, Hon G, Walker NS, Lo Conte L, Koehl P, Levitt M, Brenner SE. The ASTRAL Compendium in 2004. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D189–192. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hutchinson EG, Thornton JM. PROMOTIF-a program to identify and analyze structural motifs in proteins. Protein Sci. 1996;5:212–220. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560050204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H, Shindyalov IN, Bourne PE. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murzin AG, Brenner SE, Hubbard T, Chothia C. SCOP: a structural classification of proteins database for the investigation of sequences and structures. J Mol Biol. 1995;247:536–540. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kabsch W, Sander C. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers. 1983;22:2577–2637. doi: 10.1002/bip.360221211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Laskowski RA. PDBsum new things. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D355–359. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Joseph AP, Bornot A, de Brevern AG. Local Structure Alphabets. In: Rangwala H, Karypis G, editors. Protein Structure Prediction. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ, USA; 2010. pp. 75–106. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kohonen T. Self-organized formation of topologically correct feature maps. Biol Cybern. 1982;43:59–69. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kohonen T. Self-Organizing Maps. 3rd ed. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rabiner LR. A tutorial on hidden Markov models and selected application in speech recognition. Proc IEEE. 1989;77:257–286. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tyagi M, de Brevern AG, Srinivasan N, Offmann B. Protein structure mining using a structural alphabet. Proteins. 2008;71:920–937. doi: 10.1002/prot.21776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tyagi M, Gowri VS, Srinivasan N, de Brevern AG, Offmann B. A substitution matrix for structural alphabet based on structural alignment of homologous proteins and its applications. Proteins. 2006;65:32–39. doi: 10.1002/prot.21087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tyagi M, Sharma P, Swamy CS, Cadet F, Srinivasan N, de Brevern AG, Offmann B. Protein Block Expert (PBE): a web-based protein structure analysis server using a structural alphabet. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W119–123. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martin A, Porter C. 2010. Available at: http://www.bioinf.org.uk/software/profit/. Accessed on 1st may 2013.

- 59.Zemla A. LGA: A method for finding 3D similarities in protein structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3370–3374. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mariani V, Kiefer F, Schmidt T, Haas J, Schwede T. Assessment of template based protein structure predictions in CASP9. Proteins. 2011;79(Suppl 10):37–58. doi: 10.1002/prot.23177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gonnet GH, Cohen MA, Benner SA. Exhaustive matching of the entire protein sequence database. Science. 1992;256:1443–1445. doi: 10.1126/science.1604319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Etchebest C, Benros C, Bornot A, Camproux AC, de Brevern AG. A reduced amino acid alphabet for understanding and designing protein adaptation to mutation. Eur Biophys J. 2007;36:1059–1069. doi: 10.1007/s00249-007-0188-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lindahl E, Hess B, van der Spoel D. GROMACS 3.0: A package for molecular simulation and trajectory analysis. J Mol Mod. 2001;7:306–317. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hess B, Kutzner C, van der Spoel D, Lindahl E. GROMACS 4: Algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J Chem Theor Comp. 2008;4:435–447. doi: 10.1021/ct700301q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.van der Spoel D, Lindahl E, Hess B, Groenhof G, Mark AE, Berendsen HJC. GROMACS: Fast, Flexible and Free. J Comp Chem. 2005;26:1701–1718. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Berendsen HJC, Postma JPM, van Gunsteren WF, Di Nola A, Haak JR. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J Chem Phys. 1984;81:3684–3690. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Duan Y, Wu C, Chowdhury S, Lee MC, Xiong G, Zhang W, Yang R, Cieplak P, Luo R, Lee T, Caldwell J, Wang J, Kollman P. A point-charge force field for molecular mechanics simulations of proteins based on condensed-phase quantum mechanical calculations. J Comput Chem. 2003;24:1999–2012. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Impey RW, Klein ML. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J Chem Phys. 1983;79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hess B, Bekker H, Berendsen HJC, Fraaije JGEM. LINCS: a linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J Comput Chem. 1997;18:1463–1472. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Essmann U, Perera L, Berkowitz ML, Darden T, Lee H, Pedersen LG. A smooth particle mesh ewald potential. J Chem Phys. 1995;103:8577–8592. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Morgunova E, Dauter Z, Fry E, Stuart DI, Stel'mashchuk V, Mikhailov AM, Wilson KS, Vainshtein BK. The atomic structure of Carnation Mottle Virus capsid protein. FEBS Lett. 1994;338:267–271. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80281-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hopper P, Harrison SC, Sauer RT. Structure of tomato bushy stunt virus. V. Coat protein sequence determination and its structural implications. J Mol Biol. 1984;177:701–713. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.