Abstract

Studies of peer crowds show promise for enhancing public health promotion and practice through targeting. Distinct images, role models, and social norms likely influence health behaviors of different peer crowds within health disparity groups. We describe peer crowds identified by Black young people and determine whether identification with them is associated with smoking.

Data from Black young people aged 13 to 20 in Richmond, Virginia, were collected via interview and online survey (N = 583). We identified the number and type of peer crowds using principal components analysis; associations with smoking were analyzed using Pearson chi-square tests and logistic regression. Three peer crowds were identified: “preppy,” “mainstream,” and “hip hop.” Youth who identify with the hip hop peer crowd were more likely to smoke and have friends who smoke and less likely to hold antitobacco attitudes than those identifying with Preppy or Mainstream crowds. Identifying with the hip hop crowd significantly increased the odds of smoking, controlling for demographic factors (OR = 1.97; 95% CI = 1.03–3.76).

Tobacco prevention efforts for Black youth and young adults should prioritize the hip hop crowd. Crowd identity measures can aid in targeting public health campaigns to effectively engage those at highest risk.

INTRODUCTION

Examining why Blacks initiate and maintain smoking is important in addressing disparities in tobacco-related health outcomes. Tobacco use is the leading cause of preventable death in the United States, contributing to a range of negative health outcomes, such as cancer, heart disease, and respiratory illness (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2004). These consequences disproportionately affect some minority racial groups, with Blacks reporting lower rates of tobacco use while experiencing the greatest health burden (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 1998) and tobacco use data do not explain why African American men have the highest rates of lung, oral, pancreatic, esophageal and larynx cancers (Fagan, Moolchan, Lawrence, Fernander, & Ponder, 2007). In addition, Blacks are less likely than Whites to receive and use tobacco cessation interventions, even after controlling for socioeconomic and health care factors (Cokkinides, Halpern, Barbeau, Ward, & Thun, 2008).

Because of these disparities, Black youth are a priority for tobacco prevention efforts. Although Black teens have a lower cigarette smoking prevalence than White teens, they report more frequent use of specific tobacco products, such as menthol cigarettes (Gardiner, 2004) and little cigars known as cigarillos or “Black and Milds” (Malone, Yerger, & Pearson, 2001; Wallace et al., 1999). Due to the unique smoking patterns and increased health risks of Black young people, targeted, innovative public health strategies are needed.

Few programs address and interventions to reduce smoking among young Blacks currently exist. Health communication campaigns are an important tool for reducing smoking among young people (Noar, 2012; Farrelly, Davis, Haviland, Messeri, & Healton, 2005). Segmentation by identification with reputation-based social groups, or peer crowds, is a promising approach for effective identification, targeting, and communication with young people at risk for smoking (Fuqua, et al., 2012; Pokhrel, Brown, Moran, & Sussman, 2010).

BACKGROUND

Tobacco companies have studied and used cultural categories that form the bases for crowd identities (such as “hip hop” [Hafez & Ling, 2006] and “hipster” [Hendlin, Anderson, & Glantz, 2010]) in marketing their products to young people. This targeting suggests that identification with peer crowds may be an important factor affecting smoking, and if so, tobacco control programs culturally targeting specific youth crowds may be an efficient and effective way to identify and reach youth at highest risk (Poland et al., 2006).

Young people relate to their peer environment through identification with these crowds and tend to consider themselves and others as belonging to widely recognized and labeled social types (Sussman, Pokhrel, Ashmore, & Brown, 2007). Peer crowds are generally defined as reputation-based social types with distinct life-style norms, and identification with some peer crowds is associated with health risk behaviors (Pokhrel, Brown, Moran, & Sussman, 2010). This association can be explained using social identity theory (SIT). The potential importance of social identity as a factor in health behavior is highlighted in SIT; where culturally-specific symbolic meanings are attached to behaviors or groups and in-turn influence behaviors of individuals who belong or aspire to belong in social groups (Hogg 1992; Terry, Hogg, and White 1999; Tajfel and Turner 1979). According to this perspective, health behaviors can be normative in some cultural contexts and have symbolic meanings that make them socially valuable (Simons-Morton and Farhat 2010; Umberson, Crosnoe, & Reczek, 2010). Targeted marketing efforts on the part of industries, such as the tobacco industry, can be viewed as attempting to shape norms and meanings related to health behaviors to sell products (Umberson, Crosnoe, & Reczek, 2010).

Peer crowd identity is also particularly well suited for developing health communication campaigns because social identities reflect how individuals think about themselves and are therefore highly salient and authentic for those individuals, something that health disparities researchers have recommended (Fagan et al., 2004). While prior studies have included youth with different racial identities, to the authors’ awareness this is the first study using peer crowd identities to segment within a racial disparity population.

Identifying high risk peer crowds may help campaign developers develop more effective and efficient campaigns for Black young people. Health communications research recommends that campaigns segment populations using formative research so that campaigns can efficiently focus resources and craft messages for the highest risk individuals (Noar, 2012) with an understanding of the norms held by these segments (Stewart-Knox 2005). Accordingly, this study set out to describe identification with peer crowds widely recognized by Black youth and to examine associations between this identification and smoking. We hypothesize that crowd identity is associated with smoking among Black young people. Specifically, we expect that (1) some social identities will be more strongly associated with smoking and having friends who smoke and that (2) some of these identities will also be more strongly associated with antitobacco attitudes than others.

METHODS

To identify social identities salient to this population, this study included a preliminary assessment that was used in developing the survey items used to measure social idenity. Respondents’ social identities were measured using a process that was adapted from Brown et al.’s (2008) Social Type Rating (STR) procedure. The STR procedure allows for crowd types to be defined by the population. It uses an inductive approach to discover social identities that meaningfully distinguish people in a population into groups, and then uses these identities to develop survey measures that are relevant from the perspective of that population. Accordingly, the survey items used in this study were created based on preliminary analysis using data from the priority population to unsure their validity.

Instead of relying on verbal labels to identify different peer crowds, we used image-based measures developed by Rescue Social Change Group called the I-Base. These image-based measures more closely match the lived experience of young people, who often express their peer crowd affiliations visually (Brown et al., 2008). Identity groupings could be easily compared using the standardized set of images rather than verbal labels. This was preferable to using verbal labels since such labels involve more interpretation by participants and researchers, potentially introducing additional measurement error and bias.

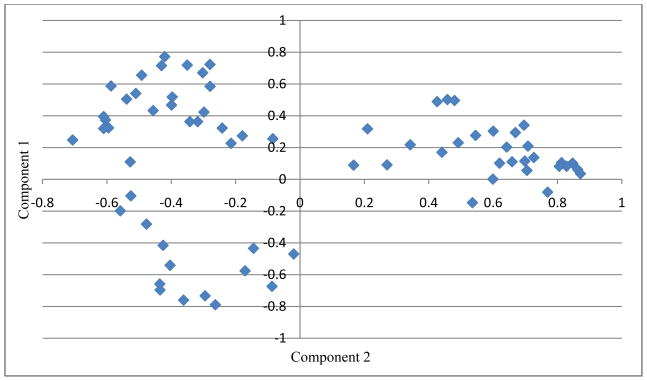

Preliminary analyses were conducted to develop the novel image-based survey items for the study using existing data collected as part of an intervention effort in the Richmond, VA area. These data were collected during ten semi-structured interviews. The participants were recruited through a partnership with a community youth organization. Participants were aged 16–20, eight of them were female, two were male, and all were Black. Respondents organized a set of sixty-nine I-Base images of demographically matched males and females into groups representing the peer crowds in their social environment. Results were recorded for each participant. Using these data the probabilities of every possible pair of images being grouped together were calculated. The groups of images consistently reported by the participants were identified using a principle components analysis (PCA) of the probabilities associated with each pairing (N=2,346). PCA was used as a data reduction technique to generate variables (components) explaining variance in the probability of images being grouped together (affinity). To ease interpretation, theresults were limited to the first two components and graphed. Figure 1 displays the final scatter plot graph of each image using the values of the first two components (factor loadings) as measures of affinity.

Figure 1.

Image Affinity based on the Two Primary Principal Components

Graphing the images in this way displays how the images were sorted across all participants, with images having high affinities with each other appearing clustered together on the graph. Crowd identity types were defined by two researchers who independently evaluated the graphed data to define clusters. Resulting definitions of clusters were compared and discussed until consensus was reached. In cases where consensus was not reached by both researchers on an image, the case was considered too ambiguous for categorization and not used in the primary study. Three crowds within the Black youth social environment emerged from the data. These groups were labeled based on the interview participants’ descriptions as “hip hop,” “preppy,” and “mainstream.”

Study Data

The primary study involved collecting online survey data. The survey was conducted October–December 2009, with Black teens in two metropolitan areas in Virginia: Norfolk-Portsmouth-Newport News (Norfolk) and Richmond-Petersburg (Richmond). The entire sample N = 727, aged 13–20, 30.5% male and 69.5% female, 82.4% Black, 54.4% were in the Richmond area, 45.6% were in the Norfolk area. The analyses were restricted to Black respondents, resulting in a sample with N = 599, aged 13–20, 28.9% male and 71.1% female. Participants were recruited through advertisements on local radio stations that had been identified by local informants as popular among Black teens. These advertisements directed participants to the website where the 15–20 minute survey was administered. All participants were directed to a webpage that provided information about the study and were asked to give written assent before being allowed to complete the anonymous online survey. As an incentive, each participant had a one in ten chance to receive a $60 gift card. These data were collected in accordance with a protocol approved by the Independent Review Consulting IRB (now Ethical & Independent Review Services).

Measures

The following measures were used to analyze the survey data.

Demographic Characteristics

Age as of December 31, 2009 was calculated using reported date of birth, and categorized into years. Education level was self-reported by the respondents in a survey item with the answer choices: (1) attending high school in Virginia, (2) attending a high school not in Virginia, (3) high school graduate, or (4) dropout. Race was measured using responses to two survey questions asking respondents if (1) they consider themselves to be Hispanic and (2) they consider themselves to be Black, White, Asian, Pacific Islander, Native American, or Other race. These analyses were restricted to the cases that self-reported as Non-Hispanic Black.

Crowd Identity

We used images to represent possible peers with whom participants can identify to measure crowd identity. This provided information about whether the participants socially identified with some images and not others. Because we previously identified the crowd identities of the images, we assumed that identifying with some images and not others tells us about the participants’ own identities.

Thirty-six images were chosen for the survey, based on how consistently they were identified with peer crowds in the preliminary analyses. The images were displayed in two arrays due to space limitation in the survey. Survey respondents were asked to evaluate the arrays and to rank order the three images depicting individuals who best represent and least represent their friend group in each array.

Index scores for each of the crowds were developed based on the respondents’ rankings of their best and worst fitting photos. These simple index scores were calculated for each of the groups by assigning scores of 3 for images ranked as best representing the respondent’s friend group, 2 for images ranked second best, and 1 for third best. Similarly, scores of -3, -2, and -1 were assigned for images ranked first, second, and third worst fitting. This was repeated for the second picture array, and scores across the two arrays were summed for each crowd. Survey participants were assigned to one of the three crowds based on the highest of these index scores. Tie scores were categorized as “indeterminate.”

Smoking and Related Attitudes

Smoking and related attitude measures were drawn from previous studies including the Virginia Youth Tobacco Survey, Youth Risk Behavior Survey, San Diego Young Adult study, and a recent study with 12 Virginia high schools. Youth smoking was measured by use of cigarettes or “Black and Mils” (referred to as cigarillos here) since these little cigars are disproportionately popular among Black youth. The created variable was dichotomous and indicated whether the respondent smoked either of these tobacco products within the past 30 days. Respondents were also asked to report how many of their friends smoked cigarettes and cigarillos in the past month with answer choices ranging from “none of my friends” to “all of my friends.”

Four tobacco attitudes were measured by survey items that asked respondents if they agree or disagree with the following statements: “I would like to see cigarette companies go out of business,” “I want to be involved with efforts to get rid of cigarette and black and mild smoking,” “taking a stand against smoking is important to me,” and “it is important to me to live a tobacco-free lifestyle.” Response choices were presented in a Likert scale with five categories. Responses in the strongest two positive categories of agreement (“a lot” and “a great deal”) were categorized as strong agreement for each item.

Data Analysis

We calculated descriptive statistics to describe the sample of Black youth. To examine associations between peer crowds and smoking, Pearson chi-square tests were used in bivariate analyses between the crowds, tobacco-related attitudes, and smoking.

To assess the independent relationships between peer crowds and smoking, we calculated odds ratios using logistic regression predicting having smoked in at least 1 of the past 30 days while controlling for education status, sex, age, and study area. A study area variable was included to control for community-specific effects and potential selection bias due to unmeasured differences between the Norfolk and Richmond areas. Since there were more female respondents (71.1%), a sampling weight was calculated based on each respondent’s probability of selection based on gender in logistic regression analyses.

RESULTS

Twenty-two percent of respondents had smoked in the past 30 days. Of the three peer crowds, “hip hop” was the most common with 40 percent of the respondents reporting smoking, followed by “Mainstream” with 23 percent, and “Preppy” with 13 percent. There were a total of 133 (23 percent) of respondents who scored equally in two of the groups and categorized as indeterminate. Having a high proportion of friends who smoke cigarillos was comparatively higher (22 percent) than having a high proportion of friends who smoke cigarettes (15 percent). Agreement with the four tobacco attitudes ranged from about 45 percent to 79 percent, with the least agreement for desire to be involved in tobacco control and the most agreement for the importance of living a tobacco-free lifestyle.

We hypothesized that identification with some peer crowds is a predictor of smoking among Black young people. To assess this hypothesis we used bivariate and multivariate methods. The results of bivariate cross-tabulations between crowd types and tobacco variables are reported in Table 1. The association with crowd identity was statistically significant with all of the tobacco-related variables at the p < .05 level.

Table 1.

Bivariate Cross Tabulations of Crowd Identity and Tobacco Use, Peer Smoking, and Tobacco Attitudes

| Crowd Identity N (%)

|

Pearson χ2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hip Hop | Preppy | Mainstream | Indeterminate | ||

| 30-day tobacco use (cigarettes and cigarillos) | 64 (27.2) | 13 (16.7) | 21 (15.3) | 30 (22.6) | χ2 = 8.63* |

| Peer smoking | |||||

| Most or all smoke cigarettes | 54 (23.2) | 3 (3.9) | 15 (11.0) | 15 (11.3) | χ2 = 43.07*** |

| Most or all smoke cigarillos | 79 (33.8) | 7 (9.0) | 20 (14.6) | 21 (18.1) | χ2 = 42.62*** |

| Tobacco attitudes | |||||

| Like to see tobacco industry out of business | 83 (53.0) | 55 (70.5) | 91 (66.4) | 91 (69.5) | χ2 =31.22** |

| Like to be involved in tobacco control | 83 (35.6) | 42 (53.9) | 63 (46.7) | 74 (56.1) | χ2 = 26.49** |

| Taking a stand against the tobacco industry | 103 (44.2) | 54 (69.2) | 74 (54.0) | 75 (56.4) | χ2 = 28.65** |

| Tobacco-free lifestyle is imp. | 163 (69.7) | 68 (87.2) | 120 (87.6) | 110 (82.7) | χ2 = 40.42*** |

= p < .05,

= p < .01,

= p < .001.

Agrees “a lot” or “a great deal” out of a 5-point Likert scale.

Across all of the tobacco-related variables identifying with the “hip hop” crowd was significantly associated with higher smoking risk. The differences between the crowd identity types were more pronounced in the bivariate associations with peer smoking. The percentages of “hip hop” youth reporting that most or all of their friends smoke cigarettes were much higher than other crowd identity types; more than twice those for both “Preppy” and “Mainstream.” In terms of tobacco attitudes, “hip hop” youth consistently and significantly had the lowest percentages of agreement across each of the four anti-tobacco attitudes.

The odds ratios from a multivariate logistic regression model predicting having smoked in the past 30 days are reported in Table 2. These results show identification with the “hip hop” peer crowd increased the odds of having smoked by 97 percent (compared to “Mainstream”) when controlling for demographic factors and location (OR = 1.97, p < .05)..

Table 2.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Odds Ratios for 30-Day Smoking (Cigarettes and Cigarillos)

| Independent Variables | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Crowd identity | |

| Hip Hop | 1.97 (1.03, 3.76) |

| Preppy | 1.56 (.69, 3.52) |

| Indeterminate | 1.44 (.55, 3.75) |

| Mainstream | REF |

| Age in years | 1.16 (.95, 1.42) |

| Sex | |

| Female | .713 (.46, 1.12) |

| Male | REF |

| Education | |

| In high school | 1.09 (.51, 2.35) |

| High school drop-out | 1.34 (.14, 12.75) |

| High school graduate | REF |

| Location | |

| Richmond | 1.00 (.99, 1.00) |

| Norfolk | REF |

| N | 551 |

| Log pseudolikelihood | −275.02 |

DISCUSSION

These results support our hypothesis that crowd identity is associated with smoking among Black young people. This supports research on youth crowds that has consistently found peer crowd identification is associated with smoking and other risk behaviors, suggesting that these crowds represent social types with distinct health behavior norms and that they may function as a source of development and reinforcement of risk behaviors (Pokhrel et al., 2010). Our findings also extend this research to show that using peer crowd identity can be used to further refine health campaigns targeting high-risk subgroups within a health disparity population.

The method outlined in this study could be used by campaign developers in formative research projects to segment disparity populations and identify subgroups at high-risk. Health messaging and social marketing programs can use information about peer crowd identity types to craft messaging, social brands, and social marketing efforts to specifically appeal to and effectively communicate with high-risk subgroups and maximize the efficient use of resources. Health disparity researchers need to understand this potential use of crowd identity to aid in the development of interventions, particularly among vulnerable populations of young people.

Our results are consistent with prior research showing that tobacco companies developed marketing strategies to target Black young people using hip hop culture and music (Cruz, Wright, & Crawford, 2010; Hafez & Ling, 2006) as well as observations that rap artists are frequently shown smoking cigarettes or cigars in the media (Gardiner 2001) and that rap music depicts substance use more than other musical genres (Primack, Dalton, Carroll, Agarwal, & Fine, 2008). Tobacco control programs targeted to specific youth cultures are needed to address and counter these influences (Poland et al., 2006). These findings may help public health professionals to understand the cultural context of smoking for Black young people and could be used to guide the development of tobacco control interventions that are salient from their perspective.

In addition, findings suggest that peer crowd identity is associated with anti-tobacco industry attitudes. The hip hop crowd had the least anti-industry attitudes compared to the other crowds. De-normalizing the tobacco industry and its products may be a promising way to reach these youth. Exploratory research shows that using tobacco documents to reveal the exploitative nature of tobacco industry marketing aimed at Blacks may be an effective way to encourage cessation and discourage smoking (Yerger, Daniel, & Malone, 2005). Taken together, this growing body of research suggests that rather than being uniquely resistant to such messaging, this subgroup may present an opportunity for health advocates to develop tailored messages informing them of the tobacco industry’s use of hip hop culture in marketing tobacco products to Blacks..

The results of this study should be interpreted in light of its limitations. Data used were of a cross-sectional design and causal conclusions cannot be made. While we used a weight to account for the disproportionate number of females in our sample this may affect the generalizability of our findings. The recruitment method used resulted in a convenience sample with unknown biases, though we have no reason to believe that this significantly affected smoking patterns. Strengths of the research design include the systematic measurement of peer crowd identity types, but it does not allow for predictions of the relative size of each of group.

Results suggest that using this procedure with image-based measures, like those used in the I-Base, is valid for measuring crowd affiliation and that further validation and refinement is warranted. We believe that this visual approach produces results that more closely resemble the perceived social organization in the lived experiences of youth than using verbal labels alone. Overall, these findings suggest that crowd identity is a meaningful and important factor associated with smoking among Black youth, and that peer crowd identity warrants attention from researchers, health practitioners, and public health campaigns.

Future research should replicate these findings using population based samples, and assess the utility of using at-risk peer crowd identification to predict smoking and other health risk behaviors prospectively. Subsequent studies should also evaluate potential gender differences in peer crowd identification and risk behavior and identification with multiple crowds. Further research is needed to identify variation in the types of peer crowds that are associated with risk behaviors across populations. Research to assess the impact of tailoring program interventions to peer crowd identities on tobacco use prevention is also needed.

Blacks are generally at increased risk for tobacco-related diseases, and our data suggest that this risk is heightened within a subset of Blacks youth who identify with the hip hop crowd identity. Specifically, young people who identified with hip hop peers were more likely to be current smokers and have friends who smoke while also being less likely to have anti-tobacco attitudes. Distinct images, role models and social norms likely influence different peer crowds. Without understanding these distinctions, programs may find it difficult to reach those who are most at risk. Our results suggest that care may need to be taken not to inadvertently alienate high-risk youth by developing health communications targeted too generally or inappropriately toward low-risk peer crowds.

These findings are particularly useful for health promotion efforts to eliminate health disparities, as they suggest peer crowds are useful for targeting public health campaigns to subgroups at highest risk. To this end, it may be beneficial for researchers to obtain information on a crowds’ cultural and consumer preferences such as preferred websites, magazines, or venues. Such information may be particularly useful for media campaigns in adopting aesthetic, language, or media channels to best reach and positively influence members of high-risk subgroups. These enhancements are potentially more effective for interventions specifically targeting at the peer crowd level because these groups likely share more such preferences in common than those broadly defined at a demographic level.

Acknowledgments

The sponsors played no role in the conduct of the research or preparation of the manuscript. The sources for each contributor are as follows: Youn Ok Lee received funding from NCI (National cancer Institute) grant CA-113710 and the Virginia Foundation for Healthy Youth, formerly the Virginia Tobacco Settlement Foundation; Jeffrey Jordan and Mayo Djakaria received funding from the Virginia Foundation for Healthy Youth, formerly the Virginia Tobacco Settlement Foundation; Pamela May Ling received funding from NCI grant U01-154240. Jeffrey Jordan and Mayo Djakaria are currently employed by Rescue Social Change Group, the firm that collected the data used in the study and developed the I-Base survey.

Contributor Information

Youn Ok Lee, RTI International, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA.

Jeffrey W. Jordan, Rescue Social Change Group, San Diego, CA, USA.

Mayo Djakaria, Rescue Social Change Group, San Diego, CA, USA.

Pamela M. Ling, University of California, San Francisco, CA, USA.

References

- Brown BB, Herman M, Hamm JV, Heck DJ. Ethnicity and image: Correlates of crowd affiliation among ethnic minority youth. Child Development. 2008;79(3):529–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01141.x. CDEV1141 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The health consequences of smoking: Aa report of the Surgeon General. 2004 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/sgr_2004/index.htm. [PubMed]

- Cokkinides VE, Halpern MT, Barbeau EM, Ward E, Thun MJ. Racial and ethnic disparities in smoking-cessation interventions: analysis of the 2005 National Health Interview Survey. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2008;34(5):404–412. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.02.003. S0749-3797(08)00159-1 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz TB, Wright LT, Crawford G. The menthol marketing mix: targeted promotions for focus communities in the United States. Nicotine &Tobacco Research. 2010;12(Suppl 2):S147–153. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq201. ntq201 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan P, King G, Lawrence D, Petrucci SA, Robinson RG, Banks D, Marable S, Grana R. Eliminating tobacco-related health disparities: directions for future research. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(2):211–217. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.2.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan P, Moolchan ET, Lawrence D, Fernander A, Ponder PK. Identifying health disparities across the tobacco continuum. Addiction. 2007;102(Suppl 2):5–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01952.x. ADD1952 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuqua JL, Gallaher PE, Unger JB, Trinidad D, Sussman S, Ortega E, Johnson CA. Multiple peer group self-identification and adolescent tobacco use. Substance Use & Misuse. 2012;47:757–766. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.608959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner P. African American teen cigarette smoking: a review. In: Burns D, editor. Changing adolescent smoking prevalence: Where it is and why. Tobacco Control Monograph, No. 14. Bethesda, MD: NCI; 2001. pp. 213–226. NIH Publication No.02-5086. [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner P. The African Americanization of menthol cigarette use in the United States. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6(Suppl 1):S55–65. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001649478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafez N, Ling PM. Finding the Kool Mixx: how Brown & Williamson used music marketing to sell cigarettes. Tobacco Control. 2006;15(5):359–366. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.014258. 15/5/359 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendlin Y, Anderson SJ, Glantz SA. “Acceptable rebellion”: marketing hipster aesthetics to sell Camel cigarettes in the U.S. Tobacco Control. 2010;19(3):213–222. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.032599. 19/3/213 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg MA. The Social Psychology of Group Cohesiveness. Toronto: Harvester Wheatsheaf; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Malone RE, Yerger V, Pearson C. Cigar risk perceptions in focus groups of urban African American youth. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2001;13(4):549–561. doi: 10.1016/S0899-3289(01)00092-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM. An Audience-Channel-Message-Evaluation (ACME) Framework for Health Communication Campaigns. Health Promotion Practice. 2012;13(4):481–488. doi: 10.1177/1524839910386901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokhrel P, Brown BB, Moran MB, Sussman S. Comments on adolescent peer crowd affiliation: a response to Cross and Fletcher (2009) Journal of Youth & Adolescence. 2010;39(2):213–216. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9454-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poland B, Frohlich K, Haines RJ, Mykhalovskiy E, Rock M, Sparks R. The social context of smoking: the next frontier in tobacco control? Tobacco Control. 2006;15(1):59–63. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.009886. 15/1/59 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primack BA, Dalton MA, Carroll MV, Agarwal AA, Fine MJ. Content analysis of tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs in popular music. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2008;162(2):169–175. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.27. 162/2/169 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton BG, Farhat T. Recent findings on peer group influences on adolescent smoking. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2010;31(4):191–208. doi: 10.1007/s10935-010-0220-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart-Knox BJ, Sittlington J, Rugkasa J, Harrisson S, Treacy M, Santos Abaunza P. Smoking and peer groups: Results from a longitudinal qualitative study of young people in Northern Ireland. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2005;44:319–414. doi: 10.1348/014466604X18073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman S, Pokhrel P, Ashmore RD, Brown BB. Adolescent peer group identification and characteristics: a review of the literature. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(8):1602–1627. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.11.018. S0306-4603(06)00351-0 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, Turner JC. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In: Austin WG, Worchel S, editors. The social psychology of intergroup relations. Monterey, CA: Brooks-Cole; 1979. pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Terry DJ, Hogg MA, White KM. The theory of planned behaviour: Self-identity, social identity and group norms. British Journal of Social Psychology. 1999;38:225–244. doi: 10.1348/014466699164149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Tobacco use among US racial/ethnic minority groups. Atlanta GA: U.S. DHHS, CDC, National Center for Chronic Disease and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 1998. Retrieved from http://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/ps/access/NNBBFR.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, Crosnoe R, Reczek C. Social relationships and health behavior across the life course. Annual Review of Sociology. 2010;36:139–157. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-120011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JM, Jr, Forman TA, Guthrie BJ, Bachman JG, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. The epidemiology of alcohol, tobacco and other drug use among black youth. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60(6):800–809. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.800. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10606492?dopt=Citation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yerger VB, Daniel MR, Malone RE. Taking it to the streets: responses of African American young adults to internal tobacco industry documents. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2005;7(1):163–172. doi: 10.1080/14622200412331328385. K6V55L437V1661Q3 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]