Abstract

Objectives

The present study investigated the temporal association between life event stressors relevant to older adults and depressive symptoms using a micro-longitudinal design (i.e., monthly increments over a six-month period). Existing research on stress and depressive symptoms has not examined this association over shorter time periods (e.g., monthly), over multiple time increments, or within-persons.

Design

An in-person initial interview was followed by six monthly interviews conducted by telephone.

Setting

Community.

Participants

Data were drawn from a study of 144 community-dwelling older adults with depressive symptoms.

Measurements

Stressful life events were measured using the Geriatric Life Events Scale (GALES), and depressive symptoms were assessed with the Short -Geriatric Depression Scale (S-GDS).

Results

Using multilevel modeling, 31% of the S-GDS' and 39% of the GALES' overall variance was due to within-person variability. Females and persons with worse health reported more depressive symptoms. Stressful life events predicted concurrent depressive symptoms, but not depressive symptoms one month later.

Conclusions

The lack of a time-lagged relationship suggests that older adults with depressive symptoms may recover more quickly from life stressors than previously thought, although additional research using varying time frames is needed to pinpoint the timing of this recovery as well identify older adults at risk of long-term effects of life stressors.

Keywords: older adults, depressive symptoms, stressful life events, variability, longitudinal

Objective

Depression is a significant concern facing older adults with 2.3% meeting criteria for major depressive disorder1 and 4.8% meeting criteria for a major depressive disorder or dysthymia.2 Estimates of subthreshold depressive symptoms are higher (9.8%).3 Depressive symptoms are associated with serious consequences including increased health-care costs,4,5 health service use,6,7 caregiver burden,8 and mortality.9,10 Given the prevalence and consequences of depression in late-life, investigation of contributing factors is warranted.

Stress is a factor implicated in the etiology of depressive symptoms. According to Lazarus and Folkman's theory of stress and coping,11 stress is implicated in the development of immediate (e.g., negative feelings) and long-term effects (e.g., well-being). This association is mediated by the processes of appraisal and coping.11 If the demands of the stressor appear to outweigh resources, depression can result. 11 Literature has examined this process with two classes of stressors, daily hassles (routine challenges of day-to-day living such as work) and stressful life events (major events that occur with less frequency). Within both areas of study, researchers have demonstrated associations between stress and depressive symptoms, albeit via differing methodologies. According to the kindling/sensitization theoretical model12, the association between stressors and depressive episodes can lessen overtime as the individual becomes sensitized. This theoretical perspective highlights the importance of examining the association of stress and depression, within individuals, over time.

Daily Hassles

Daily hassles studies have typically employed repeated measures (7-14 days), assessed stress over short time periods (e.g., using daily diaries), and examined stress in relation to the outcome of affect. The use of repeated measures designs in daily hassles research has enabled the study of variations within-persons as well as the study of longitudinal relationships between stress and depressive symptoms. Examining within-person fluctuations represents a shift from assessing mean-levels of stress and depressive symptoms and comparing across individuals. These fluctuations are worthwhile to examine as they can represent as much, or more, variability than seen between-persons (e.g., 59% of the variability in depressive symptoms13 and 46% of the variability in psychological distress14). Furthermore, the examination of longitudinal relationships in repeated-measures designs is essential for: a) reducing the influence of confounding variables by using participants as their own controls;15 and b) the examination of the temporal sequencing of variables through lagged analyses.

Stressful Life Events

In contrast to the methodology used in daily hassles studies, research on life events in community-dwelling older adults (age 50+) and the oldest old (age 85+) has typically employed one or two times of measurement,16–23 assessed variables over a longer time period (e.g., past 12 months except for two studies [past 3 and 6 months]),16–26 and examined stress in relation to more severe outcomes (i.e., depressive symptoms or diagnoses)16–27. Importantly, the lack of repeated measure designs and the use of lengthy time frames precludes the study of the ‘durability’ of life events stressors.

A small number of studies have employed repeated measures designs to investigate the timing and durability of relationships between stressful life events and depressive symptoms.24,26,27 Two of these studies24,26 did not find durability of life events stressors, reporting the presence of stressful life events was associated with depressive symptoms concurrently, but stressful life events at one time point did not predict depressive symptoms at follow-up. One possible explanation is that stressful life events may not have long-lasting effects on depressive symptoms. Another possible explanation for the lack of a lagged relationship between stressors and depressive symptoms is the use of long timeframes (six months),24,26 which diluted the strength of the association. One study reported that non-health related life events may predict later depressive symptoms and vice versa.27 However, due to the lengthy time interval between assessments (three years), the authors could not specify a timeframe in which stressful life events were associated with depressive symptoms.

The present study extends previous longitudinal studies of stressful life events and depressive symptoms by borrowing methodology from daily hassles research in order to examine timing and durability of their relationships. Specifically, a repeated measure design (six time points) was employed over shorter time intervals (monthly) than previous studies of life events. By using a condensed timeframe, the possible lagged associations between life event stressors and depressive symptoms can be uncovered. Using a shorter time scale can reduce memory distortions that occur over a longer period of time. An intermediate time period (monthly) is reasonable for examining short-time variability, given that major life stressors are unlikely to substantially fluctuate on a daily or weekly basis. Findings could have theoretical implications for our understanding of the timing and durability of relationships between stressful life events and depressive symptoms, as well as possible clinical implications for timing and focus of interventions for depressive symptoms.

The aim of the study was to examine the longitudinal associations between stressful life events and depressive symptomatology on a monthly basis in older adults with depressive symptoms. Specifically, the study examined whether: a) a higher number of stressors were concurrently (within the same month) associated with a higher number of depressive symptoms; and b) a higher number of stressors predicted a higher number of depressive symptoms in the following month. We hypothesized that stressors would be concurrently associated with depressive symptoms. The examination of lagged effects is exploratory in that the timeframe of the present study is considerably shorter than previous research and may, therefore, reveal novel findings. Additionally, possible covariates (age,16 sex,16,21,28,29 health status,21,29 and poverty status30,31) of depressive symptoms and potential moderators (age16 and sex29) of the relationship between stressors and depressive symptoms were examined. Given the associations mentioned above, we hypothesized that depressive symptoms would be higher for participants who were younger, female, had worse health status, and were living in poverty. We also hypothesized that the relationship between stressors and depressive symptoms would be stronger for younger and female participants.

Methods

Participants

Data for this study were drawn from an observational study investigating initiation and longitudinal patterns of utilization of specialty mental health services among older adults with depressive symptoms.32 Therefore, participants were included in the original study if they had depressive symptoms (i.e., score of ≥5 on the Short-Geriatric Depression Scale [S-GDS],33 were not receiving any specialty mental health services at study entry, and passed a cognitive screener.34 Participants were required to screen negative for substance misuse.35 Although the parent study assessed mental health service use, 32 the use of services was not associated with S- GDS scores and was not included in the present analyses.

The sample consisted of 144 community-dwelling participants recruited from a variety of community-based social service and housing agencies. The average age of participants was 75.5 years. The majority of participants were female (79.2%), had at least a high school education (74.4%), were primarily Caucasian (72.2%), followed by Black (23.6%), Multi-racial (2.8%), and Asian (1.4%). The majority of the sample was non-Hispanic (90.8%). Participants were primarily widowed (44.4%) or divorced (31.3%), or married (16.0%), and most of the sample lived alone (65.3%). Half of the sample was living below the 2008 poverty line. Most described their health as ‘fair’ (45.1%) or ‘good’ (27.1). The mean S-GDS score at study entry was 8.3 (SD = 2.7) and at follow-up times 1-6 respectively, standard deviation (5.7 [3.8], 5.6 [3.6], 5.3 [3.8], 5.3[3.6], 4.7[3.6], 4.9[4.0]).

Measures

Background Information

Participants provided information regarding age, sex, race and ethnicity, annual household income, and perceived health status (poor, fair, good, very good/excellent).

Stress

The Geriatric Adverse Life Events Scale (GALES) checklist of 26 items was used to assess acute, major life events.16 At the initial interview, participants were asked about events that had occurred in the prior year; at the monthly follow-up interviews, they were asked about events occurring within the past month. Given the differences in reporting timeframes for the initial and follow-up interviews, only the six follow-up assessments were analyzed for the present paper. Stressful events fell into one of six categories: financial/work difficulties, physical illness/accident, interpersonal conflicts, interpersonal loss, disruption in living situation, and other. Interrater reliability coefficients for the GALES range from 0.96 to 0.99.16

Depressive Symptoms

The Short - Geriatric Depression Scale (S-GDS)33 was used to assess depressive symptoms. The S-GDS consists of 15 items. The established cut-off for depression of ≥5 results in 86% sensitivity and 67% specificity.36 The S-GDS also has demonstrated good sensitivity to change over time.37 The S-GDS score was used as a continuous variable in the analyses. Cronbach's alpha for the six assessments were as follows: .82, .80, .83, .81, .83, and .86.

Procedure

After a complete description of the study, participants signed a written informed consent approved by the University of South Florida IRB. Data collection took place from December 2007 to August 2009. An initial interview was conducted in-person, followed by six monthly interviews by telephone. Only data from the six follow-up interviews were used in the analyses. Interviewers were trained counselors or research assistants. All interview data were reviewed by the Project Coordinator.

Data Analysis

The first step was to determine the amount of the total variance that could be attributed to within-person variability in order to justify the examination of longitudinal relationships. This was accomplished through implementation of a predictor-free multilevel model (MLM).38 Estimation of a predictor-free model for GALES and S-GDS allowed for calculation of the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), which serves as an index of the within- and between- person variability to be explained.38 Subtraction of the amount of variance due to between-person differences from the total amount of variance yields an estimation of within-person variance.

To accomplish the primary study aim, monthly GALES ratings were used to predict depressive symptomatology (S-GDS), applying MLM. This provided the opportunity to examine how well stressful life events predicted depressive symptomatology both within (level 1: across months) and between (level 2: across persons) persons. Level 1 submodels addressed questions such as: “In months in which a person reports above-average stressful life events, does s/he also experience more depressive symptomatology?” Level 1 analyses provide information about “intrapersonal variability”. Level 1 submodels also addressed questions such as: “Following a month in which a person reported above-average stressful life events, does s/he subsequently experience more depressive symptomatology?” Level 2 submodels examined questions like: “Do people who generally experience less stressful life events also report lower levels of depressive symptomatology?”

Participant attrition and missing data are common problems in longitudinal designs. However, participants with missing data are not excluded from analyses within a MLM framework.38 Model building was conducted in a hierarchical manner, such that the dependent variable (S-GDS) was predicted by two increasingly complex models. Model 1 included no predictor estimates and was parameterized to allow for estimation of the ICC and subsequent fit statistics. Model 2 included the addition of the time-invariant covariates of age, sex, education, health status, and poverty status, and also included intrapersonal mean-level and intrapersonal variability (both person-centered and person-centered lagged) in stressful life events. Therefore, Model 2 predicted monthly depressive symptomatology with: average level of depressive symptomatology (β00), demographic variables [age (β01), sex (β02), health status (β03), and income (β04)], mean-level stressful life events [between-person; (β05)], person-centered stressful life events [within-person; (β10)], person-centered lagged stressful life events [within-person; (β20)], random coefficients of the person-centered stressful life events (r1i) and person-centered lagged stressful life events (r2i), random error term (eit), and random residual component (roi). The specifics of MLM are beyond the scope of this paper. Interested readers are referred to other sources.38

In follow-up analyses, possible moderators (age and sex) of the relationship between stressful life events and depressive symptoms were examined. We re-estimated the final MLM predicting depressive symptoms from stressful life events also including interaction terms between both age and sex and within-person GALES scores.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The mean number of observations for the GALES and the S-GDS over the six assessment periods were 5.30 and 5.32, respectively. All participants reported experiencing at least one stressful life event during the six-months. At study entry, the average frequencies for the different categories of stressful life events reported over the prior year were: physical illnesses (M = 1.37; SD = 1.05), interpersonal conflicts (M = 0.74; SD = 0.98), financial stressors (M = 0.69; SD = 0.63), interpersonal loss (M = 0.58; SD = 0.71), other event (e.g., difficulty getting adequate services, victim of crime, or became a caretaker, M = 0.47; SD = 0.62), and disruption of living situation (M = 0.33; SD = 0.58). Similarly, the type of event experienced most frequently over the follow-up period was physical illnesses or accidents, followed by interpersonal conflicts, and financial stressors. The type of event with the lowest frequency of occurrence was disruption of living situation.

Longitudinal Associations between Stressful Life Events and Depressive Symptomatology

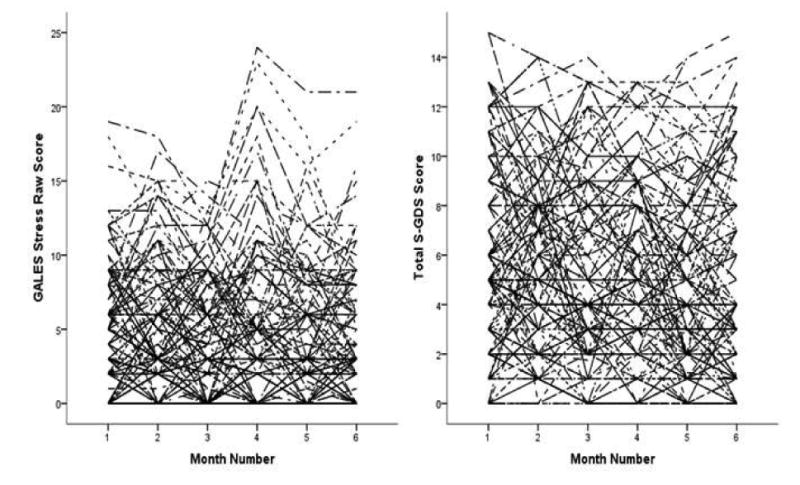

The ICC was 0.69 for S-GDS score and 0.61 for GALES score, indicating that 31% of the overall variability in S-GDS and 39% of the overall variability in GALES was a within-person phenomenon. Thus, a MLM analytical framework, which separates within- and between-person variance components, appears warranted. See Figure 1 for a graphical representation of individual GALES and S-GDS across the six assessment periods. As illustrated in Figure 1, an individual's unique report of stressful life events (GALES) and depressive symptoms (S-GDS) vary widely from month-to-month.

Figure 1.

Graph showing within-person inconsistency in GALES and S-GDS across 6 assessment periods. Each individual's data is represented by a single line.

Predictor estimates, significance levels, and model parameters are presented in Table 1. In the final MLM predicting S-GDS (Model 2), sex, health status, and GALES were significant between-person (level 2) predictors of S-GDS score. These findings suggest that females and individuals with worse health had higher S-GDS scores on average (as compared to males and individuals with better health statuses), and that individuals with above-average GALES scores (i.e., more life stressors on average) had higher than average S-GDS scores (i.e., depression).

Table 1.

Two-Level Multilevel Model Predicting Geriatric Depression Scale Score

| Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Parameter | Symbol | Estimate | SE | df | t | Pvalue | Estimate | SE | df | t | Pvalue |

| Intercept | β00 | 5.43 | 0.27 | 140.44 | 19.85 | 0.0001 | 1.52 | 2.31 | 107.32 | 0.066 | 0.51 |

| Age† | β01 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 107.74 | 1.3 | 0.2 | |||||

| Sex‡ | β02 | 1.56 | 0.56 | 108.65 | 2.77 | 0.007 | |||||

| Health Status§ | β03 | -0.68 | 0.26 | 107.74 | -2.64 | 0.01 | |||||

| Income | β04 | -0.0003 | 0.00002 | 107.05 | -1.53 | 0.13 | |||||

| GALES (BP) ║ | β05 | 0.52 | 0.06 | 110.01 | 8.13 | 0.0001 | |||||

| GALES (WP) ¶ | B10 | 0.14 | 0.04 | 58.68 | 3.82 | 0.0001 | |||||

| Lagged GALES (WP) ¶ | B20 | -0.0001 | 0.04 | 63.05 | -0.004 | 0.997 | |||||

| Random Effects | |||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

| Intercept | r0i | 9.7 | 1.27 | 7.67 | 0.0001 | 4.88 | 0.77 | 11.59 | 0.0001 | ||

| Residual | eit | 4.31 | 0.25 | 17.5 | 0.0001 | 3.25 | 0.28 | 6.3 | 0.0001 | ||

| GALES (WP) ¶ | r1i | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.66 | 0.51 | ||||||

| Lagged GALES (WP) ¶ | r2i | 0.03 | 0.02 | 1.47 | 0.14 | ||||||

| Model Fit | |||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

| -2LL (df)e | 3602.88 (3) | 3047.35 (7) | |||||||||

Measured in years since birth.

0 = male, 1 = female.

Measured as ‘Poor’ to ‘Very good/Excellent’.

GALES = Geriatric Adverse Life Events. BP = between-persons; WP = within-persons.

-2LL = -2 Log Likelihood (an indicator of model fit).

p < .001.

p < .01.

p < .05.

At the within-person level (level 1), person-centered GALES score was a significant predictor of S-GDS score, suggesting that during a month in which an individual experienced above-average numbers of stressors (i.e, GALES score above their intrapersonal mean) they also experienced more depressive symptomatology than average (i.e., higher S-GDS values than their average intrapersonal mean). Person-centered lagged GALES score was not a significant predictor of S-GDS score, suggesting that stressful events from the prior month did not predict S-GDS score during the subsequent month. Additionally, the random effect of person-centered GALES score was nonsignificant, which was not suggestive of individual differences in the month-to-month stressful events-depressive symptoms relationship. The final model also contained significant random intercept and residual-related variances, suggestive of individual differences in baseline and change in GALES scores. The model explained 25% of the within-person variance and 50% of the between-person variance in S-GDS score c (representing medium to large effect sizes)39.

In follow-up analysis examining the role of age and sex as moderators of this relationship, the model resulted in poorer overall fit and indicated no significant moderation of the association between stressful life events and depressive symptoms.

Conclusions

Results from this study of community-dwelling older adults with depressive symptoms suggest two main findings: a) major stressors and depressive symptoms may fluctuate more rapidly than was previously assumed; and b) stressful life events and depressive symptoms are positively related but these relationships appear to be short-lived. Approximately a third of the total variability observed in depressive symptoms and life event stressors could be attributed to fluctuations occurring within-person. The attribution of a third of total variance to fluctuations within the individual is less than was found in daily hassles research (59%13 and 46%14) but more than found in life events research that showed these variables remained stable over time.24,27 Possibly the use of longer timeframes for assessing variables such as stress and depressive symptoms in previous studies resulted in a flattening of variation, either due to recall deficits, or an averaging effect where participants choose to respond in a manner that is representative of their ‘typical experience’ over an extended time period.

In terms of the concurrent association between stressors and depressive symptoms, the results replicated findings from both the daily hassles and the life events literature showing a positive association. Interestingly, the relationship between life event stressors and depressive symptoms appeared to be short-lived, even in this sample selected for depressive symptoms. More stressors were not associated with a higher number of depressive symptoms a month later. These results are consistent with prior research showing a lack of durability of stressors over six months.24,26 The lack of a lagged relationship provides support for the short-term association between stressors and depressive symptoms in a sample of older adults with depression, albeit insufficient information exists to pinpoint the length of this short-term association. The results support evidence that older adults with depressive symptoms are able to recover from life events in an even shorter time period than previously thought.26 What remains to be determined is how quickly older adults' depressive symptoms recover from stressful life events. It appears that even shorter time frames are warranted in future research (e.g., weekly, bi-weekly).

Both the amount of variability and the short-lived association between stressors and depressive symptoms have implications for the treatment of depression in older adults. Short-term fluctuations in stressors and symptoms may reduce the perceived need and subsequent initiation of treatment by older adults. Furthermore, rather than targeting specific stressors (the effects of which may be short-lived), interventions could benefit by emphasizing the patient's coping skills for effectively managing stressors in general. For example, problem-solving therapy prepares the individual to both recognize and then systematically develop solutions for coping with a variety of problems.40 Simply normalizing the fluctuation in stressful life events may in itself be therapeutic, enabling the older adult to both anticipate and depersonalize the occurrence of stressors.

Consistent with the recommendation to help older adults anticipate stressful life events, the results suggest that stressful life events are regular occurrences for older adults with every participant reporting at least one life event during the study period. The estimate from the present study is higher than previous research that showed 72% of older adults experienced a stressful life event over the past year.29 The higher prevalence of life events in the present sample could reflect a selection bias within the sample or potentially more accurate reporting given the monthly assessments conducted over six time points.

The study was limited by the lack of data on other factors that could influence the association between life event stressors and depressive symptoms. In particular, the analyses focused exclusively on negative life events, did not assess all individual characteristics that could influence exposure and reactivity to stressors (e.g., personality traits, sense of mastery, and experience of chronic stress), and did not assess for physical outcomes. Given the high correlations between the subjective appraisal of the stressors and the stressors themselves, the stressors could not be ‘weighted’ by the personal meaning attributed by the participants. Due to the sample size limitations, specific types of stressful life events were not analyzed that could have differentially affected depressive symptoms. The use of the S-GDS to assess depressive symptomatology is a limitation in that somatic symptoms are not assessed. Another limitation was the use of a convenience sample that exhibited depressive symptoms upon admission to the study. The use of a sample with higher levels of depressive symptomatology, however, is a strength in that treatment implications derived from the results can be applied to older adults with depressive symptoms. However, a sample with elevated symptoms at study entry could regress to the mean over time and, consequently, dampen the longitudinal association between life stressors and depressive symptomatology.

Future research is needed to examine factors that contribute to variability in the number of stressors and depressive symptomatology experienced in late-life. Additionally, as there were individual differences in the relationship strength between stressors and depressive symptoms it would be interesting to investigate factors that mediate and moderate this relationship such as the type of stressor experienced or coping style preference. Finally, given the ability of both life events and daily hassles to affect mood, it would be helpful to study the concurrent associations of daily hassles, life events, and mood.

Methodological implications include validation of an intermediate time period (monthly or shorter) to assess stressful life events and depression given the rapidity of fluctuations. Clinical implications concern the treatment of depressive symptoms in older adults. Given the extent that both stressors and depressive symptoms fluctuated, older persons may be less motivated to seek treatment during the periods of ‘respite’ from stressors and depressive symptoms. It may be beneficial to assess fluctuations over time and provide education on the recurrent nature of depressive symptoms so that the person may consider seeking treatment during periods of worse symptoms or seek treatment for prevention of symptom worsening even in less severely depressed time periods. Treatment plans may need to address the ebb and flow of stressors in the lives of older adults, recognizing that stressors are likely to recur. Lastly, the results present a hopeful picture for relief from symptoms of depression in that stressful life events did not have a delayed relationship with depressive symptoms, suggesting the potential for relatively rapid recovery in depressive symptoms for at least some older adults.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R03MH77598; PI: Gum). This study was conducted in collaboration with the Florida BRITE Program, which is supported by a grant from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (LD815) to the State of Florida Department of Elder Affairs. Joseph M. Dzierzewski was supported by an Individual Training Grant, F31-AG-032802, awarded by the National Institute on Aging.

Footnotes

Natalie Dautovich is now at the Department of Psychology, University of Alabama. Amber Gum is now at the Department of Mental Health Law and Policy, University of South Florida.

No disclosures to report.

In total, this study included 144 older adults who completed repeated assessments for 6 consecutive months yielding a total of 864 potential data points. Less than 10% of all available data were missing. As such, missing data do not appear to be problematic in the context of the present investigation. However, to confirm such an assumption, Model 2 (the final model) was re-run including a dummy code indicating whether subjects had missing S-GDS data. This model resulted in an identical pattern of results (significance levels and direction of associations) as the final model reported above. As such, missing data does not appear to be biasing the model estimates. Additionally, as lagged person-centered GALES may have been collinear with person-centered GALES, models were re-run including only lagged person-centered GALES (i.e., removing person-centered GALES) and with both person-centered GALES and a residualized lagged person-centered GALES. Both of these models resulted in an identical pattern of results (significant levels and direction of associations) as the final model reported above. As such, multicollinearity amongst predictor variables does not appear to be biasing model estimates. Lastly, the final model was re-estimated including lagged S-GDS scores to control for previous month's depressive symptoms when examining potential lagged associations. Inclusion of this variable did not substantially change the previously reported model. To increase interpretability, we chose to report the more parsimonious and simplistic model without the inclusion of lagged S-GDS. It should be noted that in the model that included S-GDS health status was only marginally significant and lagged S-GDs was a significant predictor of next month's depressive symptoms.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gum AM, King-Kallimanis B, Kohn R. Prevalence of mood, anxiety, and substance-abuse disorders for older Americans in the national comorbidity survey-replication. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17(9):769–781. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181ad4f5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Byers AL, Yaffe K, Covinsky KE, Friedman MB, Bruce ML. High Occurrence of Mood and Anxiety Disorders Among Older Adults: The National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(5):489–496. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meeks TW, Vahia IV, Lavretsky H, Kulkarni G, Jeste DV. A tune in “a minor” can “b major”: a review of epidemiology, illness course, and public health implications of subthreshold depression in older adults. J Affect Disord. 2011;129(1-3):126–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnow PD, Blasey PD, Lee DPH, et al. Relationships Among Depression, Chronic Pain, Chronic Disabling Pain, and Medical Costs. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60(3):344–350. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.3.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vasiliadis HM, Dionne PA, Préville M, Gentil L, Berbiche D, Latimer E. The Excess Healthcare Costs Associated With Depression and Anxiety in Elderly Living in the Community. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;1 doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feng L, Yap KB, Kua EH, Ng TP. Depressive symptoms, physician visits and hospitalization among community-dwelling older adults. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21(3):568–575. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209008965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fischer LR, Wei F, Rolnick SJ, et al. Geriatric depression, antidepressant treatment, and healthcare utilization in a health maintenance organization. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(2):307–312. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrow-Howell N, Proctor E. Informal caregiving to older adults hospitalized for depression. Aging Ment Health. 1998;2(3):222–231. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruce ML, Leaf PJ. Psychiatric disorders and 15-month mortality in a community sample of older adults. Am J Public Health. 1989;79(6):727–730. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.6.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schulz R, Drayer RA, Rollman BL. Depression as a risk factor for non-suicide mortality in the elderly. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52(3):205–225. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01423-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lazarus RS. Stress and Emotion: A New Synthesis. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Post RM. Transduction of psychosocial stress into the neurobiology of recurrent affective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149(8):999–1010. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.8.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hay EL, Diehl M. Reactivity to daily stressors in adulthood: The importance of stressor type in characterizing risk factors. Psychol Aging. 2010;25(1):118–131. doi: 10.1037/a0018747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neupert SD, Almeida DM, Charles ST. Age differences in reactivity to daily stressors: the role of personal control. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007;62(4):P216–225. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.4.p216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Affleck G, Zautra A, Tennen H, Armeli S. Multilevel daily process designs for consulting and clinical psychology: A preface for the perplexed. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67(5):746–754. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.5.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Devanand DP, Kim MK, Paykina N, Sackeim HA. Adverse life events in elderly patients with major depression or dysthymic disorder and in healthy-control subjects. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10(3):265–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Falcon L, Todorova I, Tucker K. Social support, life events, and psychological distress among the Puerto Rican population in the Boston area of the United States. Aging & Mental Hlth. 2009;13(6):863–873. doi: 10.1080/13607860903046552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glass TA, Kasl SV, Berkman LF. Stressful life events and depressive symptoms among the elderly. Evidence from a prospective community study. J Aging Health. 1997;9(1):70–89. doi: 10.1177/089826439700900104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holley C, Murrell SA, Mast BT. Psychosocial and vascular risk factors for depression in the elderly. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(1):84–90. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000192504.48810.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lefrançois R, Leclerc G, Hamel S, Gaulin P. Stressful life events and psychological distress of the very old: does social support have a moderating effect? Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2000;31(3):243–255. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4943(00)00083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maciejewski PK, Prigerson HG, Mazure CM. Sex differences in event-related risk for major depression. Psychol Med. 2001;31(4):593–604. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701003877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brillman IE, Ormel J. Life events, difficulties and onset of depressive episodes in later life. Psychol Med. 2001;31(05):859–869. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richardson TM, Friedman B, Podgorski C, et al. Depression and Its Correlates Among Older Adults Accessing Aging Services. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(4):346–354. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3182107e50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeon HS, Dunkle RE. Stress and depression among the oldest-old: a longitudinal analysis. Res Aging. 2009;31(6):661–687. doi: 10.1177/0164027509343541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kasen S, Chen H, Sneed JR, Cohen P. Earlier stress exposure and subsequent major depression in aging women. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25(1):91–99. doi: 10.1002/gps.2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Norris FH, Murrell SA. Transitory impact of life-event stress on psychological symptoms in older adults. J Health Soc Behav. 1987;28(2):197–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fiske A, Gatz M, Pedersen NL. Depressive symptoms and aging: the effects of illness and non-health-related events. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2003;58(6):P320–P328. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.6.p320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kessing LV, Agerbo E, Mortensen PB. Does the impact of major stressful life events on the risk of developing depression change throughout life? Psychol Med. 2003;33(7):1177–1184. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703007852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seematter-Bagnoud L, Karmaniola A, Santos-Eggimann B. Adverse life events among community-dwelling persons aged 65–70 years: gender differences in occurrence and perceived psychological consequences. Soc Psychiat Epidemiol. 2009;45(1):9–16. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murrell SA, Norris FH. Differential social support and life change as contributors to the social class-distress relationship in older adults. Psychol Aging. 1991;6(2):223–231. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.6.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Groffen DAI, Koster A, Bosma H, et al. Unhealthy Lifestyles Do Not Mediate the Relationship Between Socioeconomic Status and Incident Depressive Symptoms. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;1 doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gum AM, Iser L, King-Kallimanis B, Petkus A, Schonfeld L. Six-month longitudinal patterns of mental health service utilization by older adults with depressive symptoms: staying the course. Psychiatric Services. 2011 doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.62.11.1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Clinical Gerontology : A Guide to Assessment and Intervention. NY: The Haworth Press; 1986. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): Recent evidence and development of a shorter version; pp. 165–173. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, Hui SL, Perkins AJ, Hendrie HC. Six-item screener to identify cognitive impairment among potential subjects for clinical research. Med Care. 2002;40(9):771–781. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200209000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schonfeld L, King-Kallimanis B, Duchene DM, et al. Screening and brief intervention for substance misuse among older adults: the Florida BRITE project. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(1):108–114. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.149534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jackson R, Baldwin B. Detecting depression in elderly medically ill patients: the use of the Geriatric Depression Scale compared with medical and nursing observations. Age Ageing. 1993;22(5):349–353. doi: 10.1093/ageing/22.5.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vinkers DJ, Gussekloo J, Stek ML, Westendorp RGJ, van der Mast RC. The 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale(GDS-15) detects changes in depressive symptoms after a major negative life event. The Leiden 85-plus Study. Int J Geriat Psychiatry. 2004;19(1):80–84. doi: 10.1002/gps.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd. Routledge Academic; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 40.D'Zurilla TJ, Nezu AM. Problem-solving therapy. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2007. [Google Scholar]