Abstract

Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) promotes insulin resistance in tissues such as liver and skeletal muscle; however the influence of IL-1β on placental insulin signaling is unknown. We recently reported increased IL-1β protein expression in placentas of obese mothers, which could contribute to insulin resistance. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that IL-1β inhibits insulin signaling and prevents insulin-stimulated amino acid transport in cultured primary human trophoblast (PHT) cells. Cultured trophoblasts isolated from term placentas were treated with physiological concentrations of IL-1β (10 pg/ml) for 24 hours. IL-1β increased the phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) at Ser307 (inhibitory) and decreased total IRS-1 protein abundance but did not affect insulin receptor β expression. Furthermore, IL-1β inhibited insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of IRS-1 (Tyr612, activation site) and Akt (Thr308) and prevented insulin-stimulated increase in PI3K/p85 and Grb2 protein expression. IL-1β alone stimulated cRaf (Ser338), MEK (Ser221) and Erk1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) phosphorylation. The inflammatory pathways nuclear factor kappa B and c-Jun N-terminal kinase, which are involved in insulin resistance, were also activated by IL-1β treatment. Moreover, IL-1β inhibited insulin-stimulated System A, but not System L amino acid uptake, indicating functional impairment of insulin signaling. In conclusion, IL-1β inhibited the insulin signaling pathway by inhibiting IRS-1 signaling and prevented insulin-stimulated System A transport, thereby promoting insulin resistance in cultured PHT cells. These findings indicate that conditions which lead to increased systemic maternal or placental IL-1β levels may attenuate the effects of maternal insulin on placental function and consequently fetal growth.

Keywords: Inflammation, Insulin-Resistance, Placenta, Maternal-Fetal Exchange

1. Introduction

Chronic low-grade inflammation causes insulin resistance and is believed to contribute to the pathogenesis of obesity and diabetes. Normal pregnancy is associated with elevated systemic inflammation and decreased insulin sensitivity in the mother, as compared to the non-pregnant state. In pregnant women who are obese or have gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), inflammation is increased further, as evidenced by the elevation of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β (IL -1β), IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) in maternal serum (Basu, Haghiac, Surace et al., 2011, Catalano, Presley, Minium et al., 2009, Challier, Basu, Bintein et al., 2008, Madan, Davis, Craig et al., 2009, Roberts, Riley, Reynolds et al., 2011). Pregnant women with obesity and/or GDM are also more insulin resistant than normal pregnant women (Norman and Reynolds, 2011). In addition, recent studies indicate that the placentas of obese women exhibit increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines either through increased systemic inflammation in the mother, infiltration of maternal macrophages into the placenta, or via de novo activation of placental inflammatory pathways (Basu, Leahy, Challier et al., 2011, Challier et al., 2008, Roberts et al., 2011).

IL-1β is one of the major pro-inflammatory cytokines produced by both macrophages and the placenta. IL-1β binding to IL-1 type I receptor activates a number of inflammatory pathways including nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) and c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), which cause insulin resistance by attenuating insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) activation (Maedler, Dharmadhikari, Schumann et al., 2009). IL-1β is linked to diabetes through defective insulin secretion in pancreatic islets (Maedler, Sergeev, Ris et al., 2002) and increased IL-1β production in adipose tissue of obese individuals decreases whole-body insulin sensitivity (Vandanmagsar, Youm, Ravussin et al., 2011). Recent clinical studies aimed at attenuating IL-1β activity in subjects with Type 2 diabetes or metabolic syndrome using human recombinant IL-1 receptor antagonist, have yielded promising results demonstrating improvements in glycaemia, insulin secretion, β-cell function and lower levels of systemic inflammation (Larsen, Faulenbach, Vaag et al., 2007, van Asseldonk, Stienstra, Koenen et al., 2011).

The insulin receptor consists of two extracellular α-subunits that bind growth factors and two transmembrane β-subunits mediating the intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity (Lee and Pilch, 1994). Activation of the insulin receptor leads to tyrosine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrates (IRS-1 and 2). In addition to the insulin receptor, IRS proteins are also activated by insulin-like growth factor (IGF) receptors, thereby representing an integrated platform for insulin and IGF signaling. Tyrosine-phosphorylated sites on the IRS-1 protein create binding sites for various signal transducing molecules such as phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) and growth factor receptor-bound protein 2 (Grb2) (Van den Berghe, 2004). PI3K activation leads to Akt/protein kinase B signaling which is often referred to as the “metabolic pathway” of insulin signaling due to the downstream effects of Akt and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling on glucose, lipid and protein metabolism (Van den Berghe, 2004). On the other hand, Grb2 dependent activation of the Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK pathway is referred to as the insulin-mediated “growth pathway” signal based on its broad proliferative and anti-apoptotic effects (Van den Berghe, 2004).

The placenta represents the interface between maternal and fetal circulations and plays a crucial role in fetal development through a multitude of functions including nutrient transport, gas exchange and hormone production. Placental insulin signaling has been reported to be altered in pregnant women with obesity or diabetes, both conditions associated with fetal overgrowth. The placentas of these women exhibit decreased protein expression of IRS-1 and PI3K regulatory subunit p85α (Colomiere, Permezel, Riley et al., 2009). Similarly, decreased expression of insulin signaling proteins has been identified in placentas of intrauterine growth restricted (IUGR) newborns (Laviola, Perrini, Belsanti et al., 2005, Street, Viani, Ziveri et al., 2011). Collectively, these studies suggest that both excessive and restricted fetal growth are associated with altered placental insulin-signaling.

In classical insulin sensitive tissues such as skeletal muscle and liver, glucose and fatty acid transport and metabolism are regulated by insulin. In the third trimester placenta, these processes are not insulin responsive (Challier, Hauguel and Desmaizieres, 1986, Magnusson-Olsson, Lager, Jacobsson et al., 2007). Although insulin was able to stimulate glucose transport in first trimester placental villous explants (Ericsson, Hamark, Jansson et al., 2005), previous reports have established that glucose transport in human term placental explants or trophoblast cell lines is not regulated by insulin (Boileau, Cauzac, Pereira et al., 2001, Challier et al., 1986). This may be explained by the absence of the insulin-sensitive glucose transporter GLUT4 in the syncytiotrophoblast of the term placentas (Ericsson, Hamark, Powell et al., 2005), whereas the syncytium in early pregnancy expresses two insulin-sensitive glucose transporters, GLUT 4 and 12 (Ericsson et al., 2005, Gude, Stevenson, Rogers et al., 2003). However, insulin stimulates a number of other endocrine and metabolic activities in the term placenta. In response to insulin treatment, primary human trophoblast (PHT) cells from term placentas secrete human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) and progesterone (Li and Zhuang, 1991). JAr placental choriocarcinoma cell line exhibits increased mitogenesis following insulin stimulation, an effect which was dependent on Erk activity (Boileau et al., 2001). Insulin is also believed to play a key role in placental vascular remodeling and function (Hiden, Glitzner, Hartmann et al., 2009, Leach, 2011) Furthermore, uptake of amino acids by placental explants and PHT cells has been shown to be stimulated by insulin (Ericsson et al., 2005, Jansson, Greenwood, Johansson et al., 2003, Jones, Jansson and Powell, 2010).

Placental amino acid transport is positively correlated to fetal growth, with decreased transport activity in intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and increased placental amino acid transport activity in association with fetal overgrowth (Gaccioli, Lager, Powell et al., 2012, Lager and Powell, 2012). Over 20 amino acid transporters are expressed in the human placenta with System A and System L transport systems arguably the best characterized (Kudo and Boyd, 2002). System A mediates sodium-dependent uptake of small non-essential, neutral amino acids such as alanine, glycine and serine. Consequently, high intracellular concentrations of these non-essential amino acids such as glycine are then used in the exchange of essential amino acids such as leucine and phenylalanine via System L transporters.

While the downstream effects of IL-1β in non-gestational, insulin sensitive tissues such as the liver and skeletal muscle are well established, the role of IL-1β in activation of placental inflammatory pathways is largely unknown; and the effect of IL-1β, or indeed any other cytokines, on insulin signaling in the placenta has not been investigated. Thongsong et al. previously reported inhibition of System A amino acid transport in BeWo choriocarcinoma cell line following IL-1β treatment (Thongsong, Subramanian, Ganapathy et al., 2005). Furthermore, injection of pregnant rats with IL-1β decreased System A activity in isolated rat placental brush-border membrane vesicles (Thongsong et al., 2005). However, it is currently unknown if IL-1β has similar effects in PHT cells and if the previously reported effects involve attenuation of insulin signaling. We recently reported increased IL-1β protein expression in placentas of obese mothers (Aye, Ramirez, Gaccioli et al., 2013), which could contribute to insulin resistance. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that IL-1β inhibits insulin signaling and prevents insulin-stimulated amino acid transport in cultured PHT cells.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Recruitment and Tissue Collection

Pregnant healthy women with normal term pregnancies who were scheduled for delivery by elective Cesarean section were recruited following written informed consent. Placental tissue was transported back to the laboratory within 15 min for cell isolation. Placentas were coded and de-identified relevant medical information was obtained. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board UTHSCSA IRB (HSC20100262H). The early pregnancy BMI of the women included in this study ranged from 20.3 – 30.6 (mean ± sem; 24.9 ± 1.2). The maternal early pregnancy BMI did not influence the results of this study.

2.2. Primary Human Trophoblast Cell Culture

PHT cells were isolated from term placenta by trypsin digestion and Percoll purification as originally described (Kliman, Nestler, Sermasi et al., 1986) with modifications (Roos, Lagerlof, Wennergren et al., 2009). Briefly, approximately 30 – 40 g of villous tissue was dissected free of decidua and blood vessels, washed in saline and digested in trypsin (0.25%, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and DNAse I (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Digests were then poured through 70 μm cell filters (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA) and cytotrophoblast cells purified over a discontinuous 10 – 70% Percoll gradient. Cells which migrated between 35 – 55% Percoll layers were collected and cultured in 1:1 mixture of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Sigma-Aldrich) and Ham’s F-12 nutrient mixture (Invitrogen) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Atlanta Biologicals, Lawrenceville, GA), 50 μg/ml gentamicin, 60 μg/ml benzyl penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were plated in 6-well dishes at a density of 2 million per well for subsequent protein analyses or 1.2 million per well for uptake assays, and incubated in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere at 37°C. Following 18h incubation, attached PHT cells were washed twice in warmed Dulbecco’s PBS and culture media was changed daily. Trophoblast cell purity was verified by performing immunoblotting analyses to identify positive Cytokeratin-7 expression and negative Vimentin expression (Supplementary Figure A). All experiments were repeated on trophoblast cells isolated from 6 different placentas.

2.3. Cell Culture Treatments

In order to examine the effects of insulin on PHT cell signaling, pilot experiments were performed to determine the time course of the activation of insulin signaling proteins. These pilot experiments indicated that physiological concentrations of insulin (1 nM) produced the most robust effects on IRS-1 phosphorylation after 0.5h treatment, Akt, 4EBP1, c-Raf, MEK and Erk phosphorylation after 3h and amino acid uptake was increased after 18h treatment with insulin. Therefore, starting at 66h in culture, the FBS concentration in the media (DMEM + Ham’s F12) was decreased to 1% and PHT cells were treated with IL-1β for 24h with or without insulin (at time points indicated above). IL-1β concentrations used in this study represent high physiological concentrations (10 pg/ml) previously reported in serum of pregnant women at term (Kaplan, Shohat, Royburt et al., 1997). Treatment of PHT cells with IL-1β did not affect cell viability (Supplementary Figure B). Cells were treated for 24h with PBS (0.1% v/v) in vehicle controls. All treatments were suspended at 90h in culture when amino acid uptake assays were performed or cell lysates collected for protein analysis.

2.4. Amino Acid Transport

System A and System L transport activities were assessed by measuring Na+-dependent uptake of 14C-methyl-aminoisobutyric acid (MeAIB) and 2-amino-2-norbornane-carboxylic acid (BCH)-inhibitable uptake of 3H-leucine (Leu) respectively, as previously described (Roos et al., 2009). Following treatment of PHT cells as indicated above, cells plated in triplicate were washed 3 times in Tyrode’s salt solution with or without Na+ (iso-osmotic choline replacement) pre-warmed to 37 °C. Cells were then incubated with Tyrode’s salt solution (with Na+ or Na+-free with addition of 1 mM BCH) containing 14C-MeAIB (20 μM at 1.19 μCi/ml) and 3H-Leu (12.5 nM at 0.68 μCi/ml) for 8 min. Transport was terminated by washing cells 3 times with ice-cold Tyrode’s salt solution without Na+. Cells were then lysed in distilled water and the water was counted in a liquid scintillation counter. Protein content of lysed cells was determined using the Lowry method (Lowry, Rosebrough, Farr et al., 1951). Transport activity is expressed as pmol per mg of protein per minute (pmol/mg/min).

2.5. Western Blot Analyses

Cells were harvested in radioimmunoprecipitation (RIPA) buffer (50mM Tris HCl, pH7.4; 150mM NaCl; 0.1% SDS; 0.5% Na-deoxycholate and 1% Triton X100) containing protease inhibitors and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail 1 and 2 (1:100, Sigma Aldrich). Protein concentrations were determined using the bicinchoninic acid assay, as per manufacturer’s instructions using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as the standard (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA).

Equal amounts of protein (2 μg) were loaded into each well and separated on Novex 4–12% Tris Glycine Pre-cast gels (Invitrogen). Separated proteins were then transferred onto PVDF membranes (Thermo Scientific) and blocked with 5% non-fat milk powder for 1h. After washing in tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% tween (TBS-T), membranes were incubated in primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C in TBS-T containing 2.5% BSA. Primary antibodies were diluted as follows: rabbit anti- phospho-IRS-1 (Tyr612), phospho-IRS-1 (Ser307), phospho-Akt (Thr308), phospho-Erk1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), phospho-JNK1/2/3 (Thr183/Tyr185), phospho-4EBP1 (Thr37/46), phospho-cRaf (Ser338), phospho-MEK (Ser221), IRS-1, Akt, Erk, JNK, IκB-α, 4EBP1, cRaf, MEK, Cytokeratin-7 and Vimentin at 1μg/ml; and mouse anti-β-actin at 0.2μg/ml. Antibodies were obtained from sources indicated in parentheses: Cytokeratin-7 (Dako, Carpinteria, CA), Vimentin (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), phospho-IRS-1 (Tyr612) and β-actin (Sigma); all other antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). The membranes were then washed and incubated with peroxidase conjugated goat anti -rabbit (0.5 μg/ml) or -mouse antibody (0.2 μg/ml) in TBS-T with 2% BSA for 2h at room temperature and visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence using ECL Western Blotting Substrate (Pierce). Resultant images were captured on a G:Box ChemiXL1.4 (Syngene, Cambridge, UK) and bands quantified using Image J software (imagej.nih.gov). Target protein expression was normalized to β-actin expression. Each target protein/actin expression-ratio was normalized to the mean of the ratios of the control samples to give the control samples a mean value of 1. To determine whether the treatments influenced β-actin expression, membranes were also stained for total protein using Amido Black Stain (Sigma) and target protein expression quantified as previously described (Lanoix, St-Pierre, Lacasse et al., 2012). Results corrected for β-actin and total protein staining using Amido Black stain were not different (data not shown) and therefore only data obtained with β-actin normalization are given.

2.6. Data Presentation and Statistical Analysis

All studies were repeated in primary cultures from six different placentas. Data are presented as mean + SEM. Statistical significance was determined by one way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test. P<0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analysis and graph plotting was performed using Prism 5 software (Graph Pad, La Jolla, CA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. IL-1β inhibits insulin-signaling at the level of IRS-1

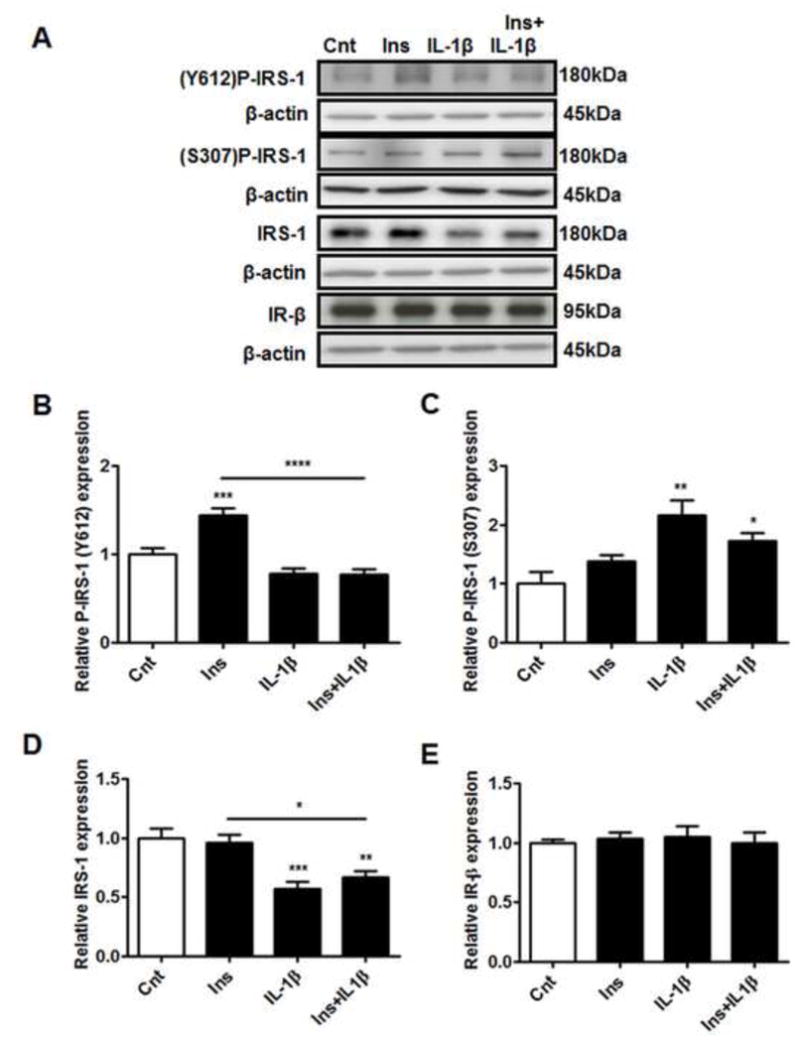

Tyr612 phosphorylation of the IRS-1 protein is associated with IRS-1 activation and positively mediates insulin-signaling (Boura-Halfon and Zick, 2009). On the other hand, phosphorylation at Ser307 leads to degradation of the IRS-1 protein and is therefore associated with inhibition of insulin-signaling (Gual, Le Marchand-Brustel and Tanti, 2005). Physiological concentrations of insulin increased phosphorylation of IRS-1 at Tyr612 by 1.5-fold (Figure 1B), indicating activation of the IRS-1 signaling pathway. In the absence of insulin, IL-1β did not alter IRS-1 Tyr612 phosphorylation. However when cells were pre-treated with IL-1β, insulin failed to increase IRS-1 Tyr612 phosphorylation. On the other hand, IL-1β increased IRS-1 phosphorylation at Ser307 by approximately 2-fold, indicating an inhibitory signal at the IRS-1 protein. Ser307 phosphorylation of IRS-1 was not observed when the cells were treated with insulin alone. In addition to the effects on IRS-1 phosphorylation, there was also a decrease in total IRS-1 protein expression by approximately 40% following treatment with IL-1β, either alone or in combination with insulin (Figure 1C). Insulin receptor-β expression was not affected by any of the treatments (Figure 1D). Hence IL-1β promotes the inhibitory serine phosphorylation, decreases IRS-1 total protein expression, and inhibits insulin-stimulated tyrosine phosphorylation of IRS-1.

Figure 1. IL-1β inhibits insulin-signaling at the level of IRS-1.

PHT cells were incubated with IL-1β (10 pg/ml) for 24h with/without insulin (1 nM) for 0.5h and protein lysates were examined by western blot analysis. A) Representative western blot images of P-IRS-1 (Tyr612), P-IRS-1 (Ser307), IRS-1, IR-β and the corresponding β-actin. Histograms illustrate relative protein expression of B) phosphorylated IRS-1 (Tyr612), C) phosphorylated IRS-1 (Ser307) D) IRS-1 and E) IR-β. Mean + sem, n=6. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001 vs. control or insulin. Cnt, control; Ins, insulin; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; IR-β, insulin receptor-β; IRS-1, insulin receptor substrate-1; Ser, serine; Tyr, tyrosine.

3.2. IL-1β prevents insulin stimulation of the metabolic pathway

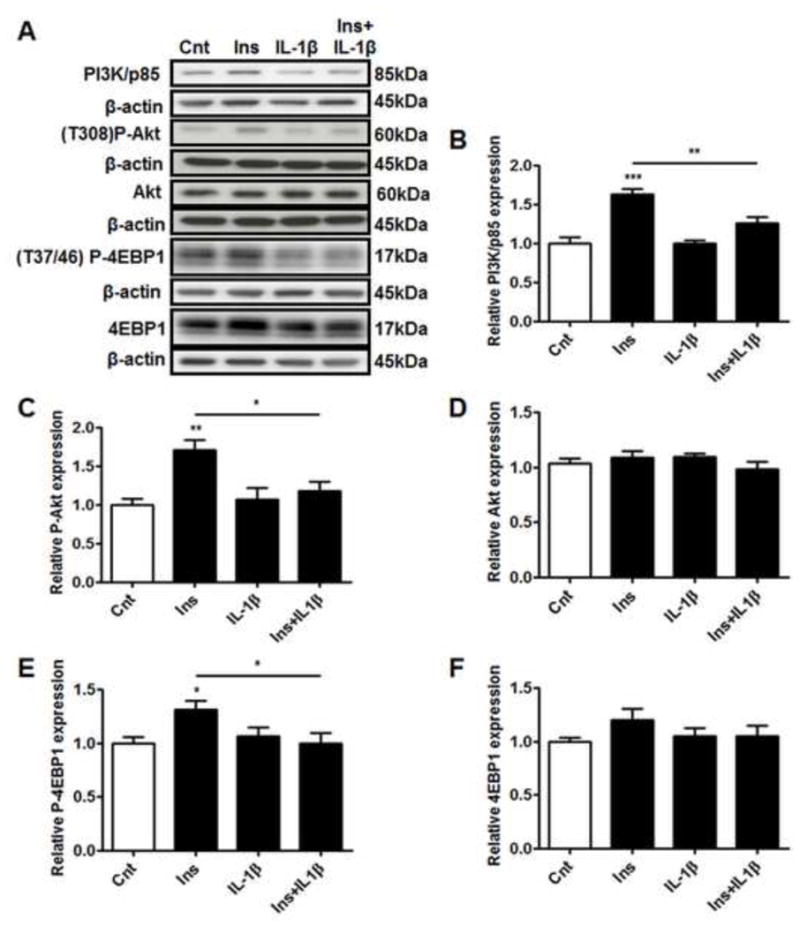

The effect of IL-1β on the metabolic insulin-signaling pathway was investigated by examining the expression of PI3K/p85 and the phosphorylation and total expression of Akt and 4EBP1 (Figure 2). Insulin treatment of PHT cells increased PI3K/p85 expression and increased phosphorylation of Akt (Thr308) and 4EBP1 (Thr37/46) by 1.3–1.7 fold but did not influence the expression of total Akt or 4EBP1 (Figure 2A–F). Although IL-1β treatment alone did not affect the phosphorylation or total expression of these proteins, IL-1β inhibited insulin-stimulated activation of PI3K/p85, Akt and 4EBP1, thus indicating an impairment of insulin-signaling in the metabolic pathway.

Figure 2. IL-1β inhibits insulin metabolic signaling pathway.

PHT cells were incubated with IL-1β (10 pg/ml) for 24h with/without insulin (1 nM) for 3h and protein lysates were examined by western blot analysis. A) Representative western blot images of PI3K/p85, P-Akt (Thr308), Akt, P-4EBP1 (Thr37/46), 4EBP1 and the corresponding β-actin. Histograms illustrate relative protein expression of B) PI3K/p85, C) phosphorylated Akt (Thr308) D) Akt, E) phosphorylated 4EBP1 (Thr37/46), F) 4EBP1. Mean + sem, n=6, *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. control or insulin. Cnt, control; Ins, insulin; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; Thr, threonine.

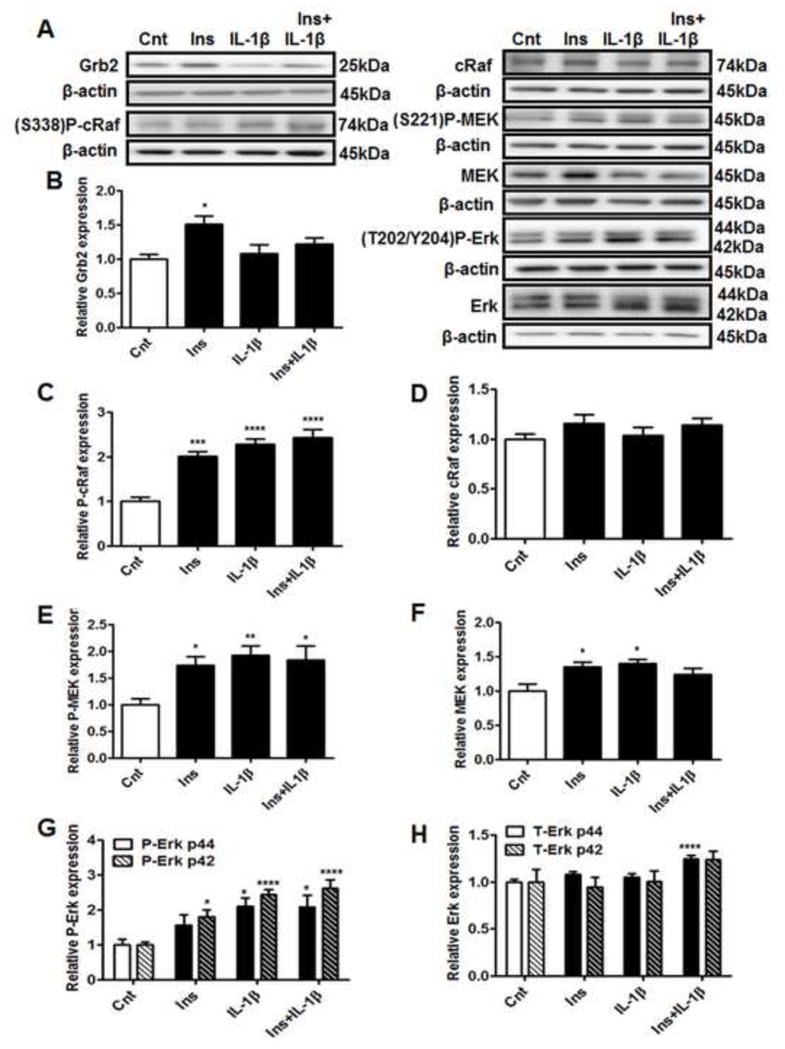

3.3. IL-1β prevents insulin stimulated Grb2 activation but stimulates Raf-MEK-Erk signaling

In order to determine the effects of IL-1β on the insulin-growth pathway, we measured the expression of Grb2 and the phosphorylation and total expression of cRaf, MEK and Erk1/2 (Figure 3). Insulin increased the expression of Grb2 by 1.5 fold (Figure 3B), as well as the phosphorylation of downstream signaling proteins cRaf, MEK and Erk2 (p42) by 1.8–2.0 fold (Figure 3C, E and G). Insulin also increased total MEK expression by approximately 1.4 fold (Figure 3F). Similar to the findings in the metabolic insulin-signaling pathway, IL-1β inhibited the insulin-stimulated increase in Grb2 expression, whereas IL-1β treatment alone did not influence basal Grb2 expression (Figure 3B). However, phosphorylation of cRaf and its downstream targets MEK and Erk1/2 were not inhibited by IL-1β (Figure 3C, E and G). Instead, IL-1β treatment either alone or in combination with insulin increased cRaf, MEK and Erk1/2 (p44/42) phosphorylation by more than 2 fold. Furthermore, the expression of MEK was increased by 1.4 fold (Figure 3F) with IL-1β treatment and Erk1 (p44) protein was significantly increased with the combination of insulin and IL-1β (Figure 3H). Collectively, these data indicate that the effects of IL-1β on IRS-1 signaling result in inhibition of the growth pathway as demonstrated by the prevention of insulin-stimulated increase in Grb2 expression by IL-1β. Furthermore, IL-1β activates the downstream Raf-MEK-Erk signaling independent of its effects on Grb2.

Figure 3. Differential effects of IL-1β on the insulin growth signaling pathway.

PHT cells were incubated with IL-1β (10 pg/ml) for 24h with/without insulin (1 nM) for 3h and protein lysates were examined by western blot analysis. A) Representative western blot images of Grb2, P-cRaf (Ser338), cRaf, P-MEK (Ser221), MEK, P-Erk1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), Erk and the corresponding β-actin. Histograms illustrate relative protein expression of B) Grb2 C) phosphorylated cRaf (Ser338), D) cRaf E) phosphorylated MEK (Ser221) F) MEK G) phosphorylated Erk1/2 (p44/42, Thr202/Tyr204) and H) Erk1/2 (p44/42). Mean + sem, n=6, *P<0.05, **P<0.01 ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001 vs. control. Cnt, control; Ins, insulin; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; Ser, serine; Thr, threonine; Tyr, tyrosine.

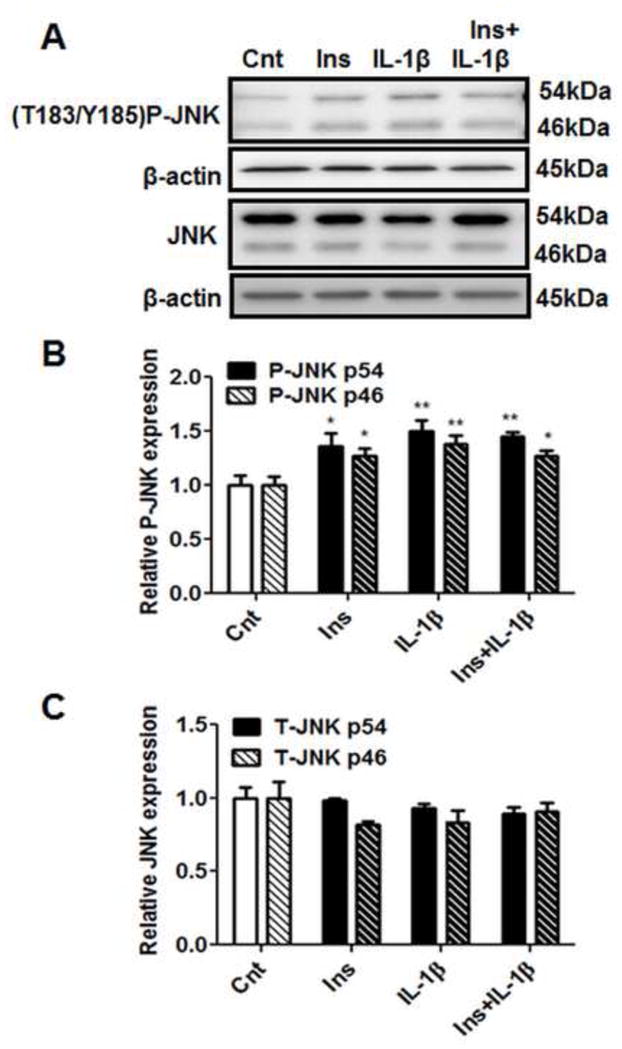

3.4. JNK is activated by insulin and IL-1β

When administered separately, both insulin and IL-1β increased the phosphorylation of both p54 and p46 JNK in cultured PHT cells (Figure 4B and C). Combination of IL-1β with insulin stimulated JNK phosphorylation but this effect was not additive compared to IL-1β or insulin treatments alone. These treatments did not significantly alter total JNK protein expression (Figure 4D and E).

Figure 4. IL-1β increases JNK phosphorylation.

PHT cells were incubated with IL-1β (10 pg/ml) for 24h with/without insulin (1 nM) for 3h and protein lysates were examined by western blot analysis. A) Representative western blot images of P-JNK (Thr183/Tyr185), JNK and the corresponding β-actin. Histograms illustrate relative protein expression of B) phosphorylated JNK (p54/46) and JNK (p54/46). Mean + sem, n=6, *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. control. Cnt, control; Ins, insulin; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; Thr, threonine; Tyr, tyrosine.

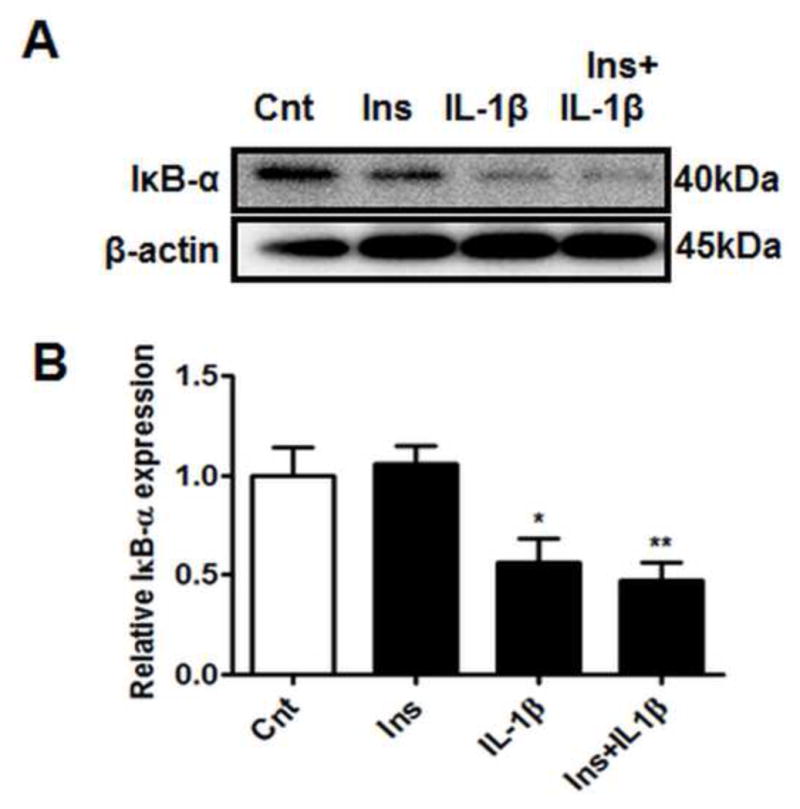

3.5. NF-κB is activated by IL-1β but not by insulin

NF-κB subunits are held in an inactive state in the cytoplasm by its inhibitory proteins; inhibitor of kappa B (IκB) subunits, the most predominant member being IκB-α. Once activated, IκB-α undergoes degradation, thereby releasing NF-κB subunits which subsequently translocate into the nucleus. Decreased IκB-α protein expression is therefore used as an indicator of NF-κB activation. While insulin treatment alone did not influence IκB-α protein expression, PHT cells treated with IL-1β (with or without insulin), displayed significantly decreased IκB-α expression (Figure 5B), indicative of NF-κB activation.

Figure 5. NF-κB pathway is activated by IL-1β.

PHT cells were incubated with IL-1β (10 pg/ml) for 24h with/without insulin (1 nM) for 3h and protein lysates were examined by western blot analysis. Decreased IκB-α expression indicates NF-κB activation A) Representative western blot images of IκB-α and the corresponding β-actin. Histograms illustrate relative protein expression of B) IκB-α. Mean + sem, n=6, *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs control. Cnt, control; Ins, insulin; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; IκB-α, inhibitor of kappa B-alpha.

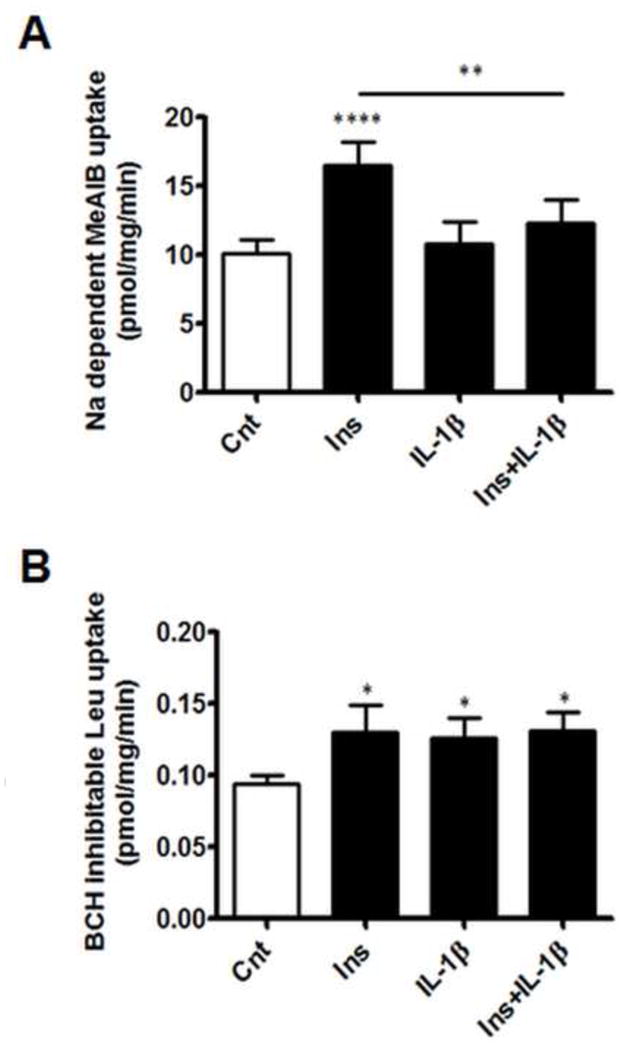

3.6. IL-1β mediates distinct effects on System A and System L transport activity

Insulin treatment of PHT cells increased System A activity by approximately 1.7-fold, consistent with previous reports in human placental fragments (Jansson et al., 2003) and PHT cells (Jones et al., 2010). IL-1β pre-treatment inhibited the effects of insulin on System A activity (Figure 6A), whereas IL-1β treatment alone did not affect System A activity in PHT cells.

Figure 6. Differential effects of IL-1β on System A and System L amino acid transport.

PHT cells were incubated with IL-1β (10 pg/ml) for 24h with/without insulin (1 nM) for 18h, prior to the transport assays. (A) Sodium dependent MeAIB uptake and (B) BCH-inhibitable leucine uptake after treatment of PHT cells as indicated above. Data represents specific transport activity in pmol/mg/min (mean + sem, n=6). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ****P<0.0001 vs. control or insulin. BCH, 2-amino-2-norbornane-carboxylic acid; Cnt, control; Ins, insulin; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; Leu, leucine; MeAIB, methylamino-isobutyric acid; Na, sodium.

In addition to System A activity, we observed a modest, approximately 1.4-fold, increase in System L mediated Leu uptake in PHT cells treated with insulin alone (Figure 6B). However, unlike System A transport, insulin-dependent System L activity was not inhibited by IL-1β. On the contrary, IL-1β stimulated System L uptake by 1.3-fold. Combining IL-1β and insulin did not modify the effects of either treatment alone.

4. Discussion

Insulin regulates a multitude of endocrine and metabolic functions of the placenta. For example, insulin increases trophoblast production of hormones such as hCG (Li and Zhuang, 1991, Ren and Braunstein, 1991) and stimulates amino acid transport (Ericsson et al., 2005). Hence knowledge of the factors which influence placental insulin sensitivity is imperative to our understanding of placental function. Pro-inflammatory cytokines are well-established inhibitors of insulin signaling in a range of tissues (Tanti, Ceppo, Jager et al., 2012), however whether placental insulin signaling is subject to modulation by cytokines is unknown. We recently reported a positive correlation between maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) and placental expression of active IL-1β (p17) protein (Aye et al., 2013) and placentas of overweight/obese mothers displayed signs of insulin resistance (Ramirez, Gaccioli, Jansson et al., 2012). These findings provided the rationale to test the hypothesis that IL-1β inhibits insulin signaling and insulin-stimulated amino acid transport in PHT cells.

IL-1β inhibited insulin signaling in PHT cells, as demonstrated by both increased Ser307 phosphorylation of IRS-1 and decreased insulin-stimulated Tyr612 phosphorylation of IRS-1. Moreover, we observed a reduction in total IRS-1 protein without any changes in IR-β, suggesting that IL-1β inhibits placental insulin signaling by down-regulating IRS-1 expression. Decreased IRS-1 expression through protein degradation leads to an inability of the tyrosine kinase activity of the insulin receptor to phosphorylate IRS-1 thereby impairing insulin signaling function and promoting insulin resistance (Gual et al., 2005). Thus, this data demonstrated that IL-1β inhibits trophoblast insulin signaling at the level of IRS-1. We then investigated whether the effects of IL-1β on IRS-1 activity prevented signaling in both the “metabolic” and “growth” arm of the insulin signaling pathway.

Consistent with our observation of IRS-1 inhibition, IL-1β inhibited insulin-stimulated PI3K/p85 expression, reduced insulin-stimulated Akt (Thr308) phosphorylation and prevented insulin-mediated 4EBP1 phosphorylation (Thr37/46). These findings are in agreement with a previous report by Jager et al., in which IL-1β decreased IRS-1 protein expression and inhibited IRS-1 and Akt signaling in adipocytes, leading to decreased insulin-stimulated glucose transport (Jager, Gremeaux, Cormont et al., 2007). Hence our findings suggest that the metabolic signal of the insulin-pathway in PHT cells is inhibited by IL-1β.

IL-1β also inhibited insulin-mediated increase in the expression of Grb2, which is the first component of the growth pathway of insulin signaling. However, when we investigated the downstream targets of Grb2, in particular cRaf, MEK and Erk1/2, insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of these targets were not inhibited by IL-1β. In contrast, IL-1β alone stimulated the phosphorylation of cRaf (Ser338), MEK (Ser221) and Erk1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204). This suggests that although IL-1β inhibited IRS-1 at both the metabolic (inhibition of insulin-stimulated PI3K/p85 expression, and phosphorylation of Akt and 4EBP1) and growth pathways (as evidenced by decrease in insulin-mediated Grb2 expression), IL-1β directly stimulated cRaf leading to the activation of cRaf and its downstream targets MEK and Erk1/2. Indeed, both insulin and inflammatory stimuli have previously been shown to activate cRaf at Ser338 (Adler, Bowne, Michl et al., 2008). The downstream effects of Ras-Raf-MEK-Erk1/2 signaling in term placental trophoblasts are currently unknown, since syncytiotrophoblasts in vivo and PHT cells isolated from term placentas have very low proliferative activity (Chan, Lao and Cheung, 1999, Kar, Ghosh and Sengupta, 2007, Morrish, Dakour, Li et al., 1997). Therefore, proliferation studies in trophoblasts isolated from first trimester placentas may be more insightful in determining the role of the insulin-growth pathway and reveal the influence of IL-1β on this pathway.

While insulin signaling has been shown to activate the Ras-Raf-MEK-Erk1/2 pathway (Kayali, Austin and Webster, 2000, Van den Berghe, 2004), a finding also confirmed in this study; Erk1/2 activity in turn inhibits IRS-1 signaling, indicating cross-talk between the growth and metabolic pathways of insulin signaling (Borisov, Aksamitiene, Kiyatkin et al., 2009). This suggests that Erk1/2 signaling in PHT cells may be involved in insulin resistance. Indeed, activation of Erk has been mechanistically linked to IRS-1 down-regulation (Fujishiro, Gotoh, Katagiri et al., 2003, Jager et al., 2007), and Erk-1 null mice are more sensitive to insulin on a high-fat diet regimen compared to wild-types (Bost, Aouadi, Caron et al., 2005).

Our findings of Erk1/2 activation by insulin and IL-1β are in agreement with our previous reports of insulin resistance in placentas of women with increasing pre-pregnancy BMI (Ramirez et al., 2012). In that study, with increasing maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and elevated serum insulin levels, we reported increased phosphorylation of placental Erk1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), but no changes in Akt (Thr308) phosphorylation. The disparate findings with respect to Akt and Erk phosphorylation were also reported by Cusi et al. in skeletal muscle of lean versus obese and type 2 diabetic male subjects which were acutely infused with insulin (Cusi, Maezono, Osman et al., 2000). They found that IRS-1, PI3K/Akt and Erk1/2 were activated in skeletal muscle of lean subjects following insulin infusion. However, when obese or diabetic subjects were infused with insulin, Erk1/2 activity was increased, but IRS-1 and PI3K remained unchanged (Cusi et al., 2000). IL-1β also stimulates cRaf which overrides the inhibitory effects on IRS-1 signaling. Furthermore, since Erk1/2 is also implicated in inflammation, this indicates that phosphorylation of cRaf, MEK and Erk1/2 by IL-1β leads to inflammatory activation.

In addition to Erk1/2, the inflammatory pathways JNK and NF-κB have also been linked to insulin resistance, and activation of both JNK and NF-κB were previously reported in the placentomes of obese sheep at mid-gestation (Zhu, Du, Nathanielsz et al., 2010). In many cell types, IL-1β is a potent activator of JNK and NF-κB, which are implicated in insulin-resistance through the degradation of IRS-1 protein (Boura-Halfon and Zick, 2009, Tanti and Jager, 2009). In this study, we observed activation of JNK and NF-κB pathways in cultured PHT cells following IL-1β treatment. Insulin also stimulated JNK phosphorylation, which has previously been shown to cause feedback inhibition of the insulin signaling cascade (Lee, Giraud, Davis et al., 2003). Taken together, these findings suggest that IL-1β activates Erk1/2, JNK and NF-κB pathways, which have been shown to inhibit insulin signaling in other tissues. Future studies are warranted to develop a mechanistic understanding of the links between IL-1β and insulin resistance in the placenta, and to establish the relative contribution of these pathways.

Several studies have demonstrated that insulin stimulates trophoblast amino acid uptake (Jansson et al., 2003, Jones et al., 2010) and increased placental amino acid transport activity is associated with increased fetal growth (Gaccioli et al., 2012, Lager and Powell, 2012). We previously demonstrated attenuation of trophoblast insulin signaling by full length adiponectin (fADN) which prevented insulin-stimulated amino acid uptake (Jones et al., 2010). Moreover, chronic infusion of pregnant mice with fADN attenuated placental insulin signaling and reduced amino acid uptake in isolated trophoblast plasma membranes resulting in decreased fetal weight (Rosario, Schumacher, Jiang et al., 2012). These in vivo findings validate the physiological significance of the results in PHT cells and indicate an essential role of placental insulin signaling in regulating fetal growth through its effects on amino acid transport. In the current study we used PHT amino acid transport as a functional read-out for insulin signaling and examined the role of IL-1β on placental amino acid transport.

The mechanisms by which insulin regulates System A transport in PHT cells are not fully established but previous reports indicate that it involves both transcriptional (Jones et al., 2010) and post-translational regulation mediated by effects on membrane trafficking by mTOR signaling (Roos et al., 2009, Rosario, Kanai, Powell et al., 2013). Whereas IL-1β treatment alone did not affect basal System A mediated uptake of MeAIB, insulin-stimulated System A activity was inhibited by IL-1β. This suggests that the effects of IL-1β on System A transport were dependent on insulin signaling and therefore IL-1β may also influence other aspects of placental function, such as placental endocrine activity which is regulated by insulin (Li and Zhuang, 1991, Perlman, Barzilai, Bick et al., 1985, Ren and Braunstein, 1991, Zeck, Widberg, Maylin et al., 2008).

Our findings that IL-1β treatment did not influence basal System A activity are in contrast to findings previously reported by Thongsong et al. who demonstrated inhibition of System A transport by IL-1β in the BeWo cell line (Thongsong et al., 2005). The discrepancies may be due to differences in cell types because BeWo cells are a choriocarcinoma cell line from first trimester placentas (Hertz, 1959, Pattillo and Gey, 1968), which may respond differently than primary trophoblast cells isolated from term placentas. Moreover, whereas we treated PHT cells with physiological concentrations of IL-1β (10 pg/ml); Thongsong et al. demonstrated decreased basal MeAIB uptake at a minimum concentration of 100 pg/ml.

Unlike System A transport, insulin-stimulated leucine uptake by System L was not attenuated by IL-1β treatment. Surprisingly, IL-1β increased System L activity either alone or in combination with insulin. Because IL-1β inhibited insulin-dependent IRS-1 phosphorylation and the downstream activation of Akt; the effects of IL-1β on leucine uptake are unlikely to be dependent on the metabolic branch of the insulin signaling pathway. Because both insulin and IL-1β significantly increased Raf-MEK-Erk1/2 phosphorylation, IL-1β and insulin-stimulated increase in System L activity may involve Erk signaling, although this remains to be confirmed. However, a role for Erk1/2 signaling in regulating System L transport was recently demonstrated in murine skeletal muscle fibres (Hamdi and Mutungi, 2011). To the best of our knowledge, the effects of IL-1β on basal System L activity have not been reported in any other cell type. However, these findings are consistent with published reports that another pro-inflammatory cytokine, TNF-α, increased leucine uptake in trophoblast plasma membrane vesicles isolated from rat placenta (Carbo, Lopez-Soriano, Fiers et al., 1996).

In conditions such as obesity and GDM, the maternal metabolic environment is characterized by numerous changes such as increased circulating levels of insulin, leptin, IGF-I and fatty acids. These changes are predicted to alter placental function (Gaccioli et al., 2012, Lager and Powell, 2012), including increased amino acid transport and therefore may explain why fetal overgrowth is more common in these conditions. However, the majority of the women with obesity and/or GDM give birth to normal sized infants, suggesting that there are other signals present which limit placental function and nutrient delivery to the fetus. IL-1β may constitute one of these factors which oppose the stimulatory effects of the maternal metabolic environment in obesity and GDM, and thus may explain why not all babies of obese and GDM mothers are large at birth.

Early in gestation, the cytotrophoblasts cells are highly proliferative and invasive (Aplin, 2010, Chan et al., 1999), properties which are lost in term cytotrophoblasts (Morrish, Bhardwaj, Dabbagh et al., 1987). Although first trimester trophoblasts were not the focus of this study, there are several reports that insulin regulates cell proliferation and invasion in first trimester human trophoblast cell lines (Mandl, Haas, Bischof et al., 2002). Insulin-dependent first trimester trophoblast cell proliferation was shown to be dependent on the insulin-growth signaling pathway as MAPK inhibitors prevented mitogenesis (Boileau et al., 2001). Regulation of trophoblast invasion by insulin is mediated, at least in part, by membrane type metalloproteinase (Hiden, Glitzner, Ivanisevic et al., 2008, Hiden, Lassance, Tabrizi et al., 2012), which in cancer cell lines have been demonstrated to be dependent on insulin-metabolic pathway involving PI3K/Akt signaling. Therefore placental insulin-resistance mediated by IL-1β or other pro-inflammatory cytokines early in gestation may impact upon placental development and consequently impair placental function.

In summary, IL-1β treatment decreased the sensitivity of the insulin signaling pathway in cultured PHT cells by down-regulation of IRS-1 protein and attenuation of the downstream signaling proteins PI-3K and Grb2, preventing insulin-dependent System A transport activity. These effects may be related to IL-1β mediated activation of Erk1/2, JNK and NF-κB, which have established roles in insulin resistance. These in vitro findings in PHT cells provide a mechanistic insight linking our previous observations in obese mothers of elevated placental IL-1β (Aye et al., 2013) and placental insulin resistance (Ramirez et al., 2012). Moreover, the findings of decreased insulin-stimulated System A transport by IL-1β suggest that IL-1β may counteract the effects of maternal hyper-insulinemia in pregnancies complicated by obesity, on placental amino acid transport and consequently limit excessive fetal growth.

Supplementary Material

Trophoblast cells were identified by western blotting analysis of Cytokeratin-7 and Vimentin. Trophoblast cell cultures express Cytokeratin-7 protein (epithelial cell marker) but do not express Vimentin (mesenchymal cell marker). Total protein homogenates from term placental tissues was used as a positive control for both Cytokeratin-7 and Vimentin. Pl Hom, placental homogenate; PHT, primary human trophoblast cells.

Cell viability was analyzed after treatment with IL-1β (10 pg/ml) for 24 h. Cell viability measured using the 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) cell viability assay. PHT cells plated in triplicate in 96 well plates at 1 × 10−5 cells per well. At the end of treatment, 1 mg/ml of MTT reagent was added to each well for 4h at 37 °C, lysed with 10% SDS and absorbance read at 570 nm. Cell viability was presented as a percentage of vehicle-treated controls. N=3, IL-1β treatments were not significantly different controls. Cnt, control; IL-1β, interleukin-1β.

Highlights.

Role of IL-1β on insulin-signaling and function was examined in placental trophoblasts.

IL-1β inhibits insulin signaling at the IRS-1 level.

IL-1β prevents insulin activation of PI3K pathway.

Insulin-stimulated System A amino acid transport is prevented by IL-1β.

IL-1β impairs insulin-signaling and insulin-mediated amino acid transport in placenta.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the help of Evelyn Miller and the staff at Labor and Delivery Unit at the University Hospital for their assistance in collecting placentas. This work was funded by NIH grant DK89989 to TLP.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Adler V, Bowne W, Michl J, Sookraj KA, Ikram K, Pestka S, Izotova L, Zenilman M, Friedman FK, Qu Y, Pincus MR. Site-specific phosphorylation of raf in cells containing oncogenic ras-p21 is likely mediated by jun-N-terminal kinase. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2008;38:47–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aplin JD. Developmental cell biology of human villous trophoblast: current research problems. Int J Dev Biol. 2010;54:323–9. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.082759ja. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aye IL, Ramirez VI, Gaccioli F, Lager S, Jansson T, Powell T. Activation of Placental Inflammasomes in Pregnant Women with High BMI. Reproductive Sciences. 2013:20. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basu S, Leahy P, Challier JC, Minium J, Catalano P, Hauguel-de Mouzon S. Molecular phenotype of monocytes at the maternal-fetal interface. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:265 e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basu S, Haghiac M, Surace P, Challier JC, Guerre-Millo M, Singh K, Waters T, Minium J, Presley L, Catalano PM, Hauguel-de Mouzon S. Pregravid obesity associates with increased maternal endotoxemia and metabolic inflammation. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19:476–82. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boileau P, Cauzac M, Pereira MA, Girard J, Hauguel-De Mouzon S. Dissociation between insulin-mediated signaling pathways and biological effects in placental cells: role of protein kinase B and MAPK phosphorylation. Endocrinology. 2001;142:3974–9. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.9.8391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borisov N, Aksamitiene E, Kiyatkin A, Legewie S, Berkhout J, Maiwald T, Kaimachnikov NP, Timmer J, Hoek JB, Kholodenko BN. Systems-level interactions between insulin-EGF networks amplify mitogenic signaling. Mol Syst Biol. 2009;5:256. doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bost F, Aouadi M, Caron L, Even P, Belmonte N, Prot M, Dani C, Hofman P, Pages G, Pouyssegur J, Le Marchand-Brustel Y, Binetruy B. The extracellular signal-regulated kinase isoform ERK1 is specifically required for in vitro and in vivo adipogenesis. Diabetes. 2005;54:402–11. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.2.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boura-Halfon S, Zick Y. Phosphorylation of IRS proteins, insulin action, and insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296:E581–91. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90437.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carbo N, Lopez-Soriano FJ, Fiers W, Argiles JM. Tumour growth results in changes in placental amino acid transport in the rat: a tumour necrosis factor alpha-mediated effect. Biochem J. 1996;313(Pt 1):77–82. doi: 10.1042/bj3130077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Catalano PM, Presley L, Minium J, Hauguel-de Mouzon S. Fetuses of obese mothers develop insulin resistance in utero. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1076–80. doi: 10.2337/dc08-2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Challier JC, Hauguel S, Desmaizieres V. Effect of insulin on glucose uptake and metabolism in the human placenta. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1986;62:803–7. doi: 10.1210/jcem-62-5-803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Challier JC, Basu S, Bintein T, Minium J, Hotmire K, Catalano PM, Hauguel-de Mouzon S. Obesity in pregnancy stimulates macrophage accumulation and inflammation in the placenta. Placenta. 2008;29:274–81. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan CC, Lao TT, Cheung AN. Apoptotic and proliferative activities in first trimester placentae. Placenta. 1999;20:223–7. doi: 10.1053/plac.1998.0375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colomiere M, Permezel M, Riley C, Desoye G, Lappas M. Defective insulin signaling in placenta from pregnancies complicated by gestational diabetes mellitus. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009;160:567–78. doi: 10.1530/EJE-09-0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cusi K, Maezono K, Osman A, Pendergrass M, Patti ME, Pratipanawatr T, DeFronzo RA, Kahn CR, Mandarino LJ. Insulin resistance differentially affects the PI 3-kinase- and MAP kinase-mediated signaling in human muscle. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:311–20. doi: 10.1172/JCI7535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ericsson A, Hamark B, Powell TL, Jansson T. Glucose transporter isoform 4 is expressed in the syncytiotrophoblast of first trimester human placenta. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:521–30. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ericsson A, Hamark B, Jansson N, Johansson BR, Powell TL, Jansson T. Hormonal regulation of glucose and system A amino acid transport in first trimester placental villous fragments. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R656–62. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00407.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fujishiro M, Gotoh Y, Katagiri H, Sakoda H, Ogihara T, Anai M, Onishi Y, Ono H, Abe M, Shojima N, Fukushima Y, Kikuchi M, Oka Y, Asano T. Three mitogen-activated protein kinases inhibit insulin signaling by different mechanisms in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:487–97. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaccioli F, Lager S, Powell TL, Jansson T. Placental transport in response to altered maternal nutrition. Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease. FirstView. 2012:1–15. doi: 10.1017/S2040174412000529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gual P, Le Marchand-Brustel Y, Tanti JF. Positive and negative regulation of insulin signaling through IRS-1 phosphorylation. Biochimie. 2005;87:99–109. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2004.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gude NM, Stevenson JL, Rogers S, Best JD, Kalionis B, Huisman MA, Erwich JJ, Timmer A, King RG. GLUT12 expression in human placenta in first trimester and term. Placenta. 2003;24:566–70. doi: 10.1053/plac.2002.0925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamdi MM, Mutungi G. Dihydrotestosterone stimulates amino acid uptake and the expression of LAT2 in mouse skeletal muscle fibres through an ERK1/2-dependent mechanism. J Physiol. 2011;589:3623–40. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.207175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hertz R. Choriocarcinoma of women maintained in serial passage in hamster and rat. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1959;102:77–81. doi: 10.3181/00379727-102-25149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hiden U, Glitzner E, Hartmann M, Desoye G. Insulin and the IGF system in the human placenta of normal and diabetic pregnancies. J Anat. 2009;215:60–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2008.01035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hiden U, Glitzner E, Ivanisevic M, Djelmis J, Wadsack C, Lang U, Desoye G. MT1-MMP expression in first-trimester placental tissue is upregulated in type 1 diabetes as a result of elevated insulin and tumor necrosis factor-alpha levels. Diabetes. 2008;57:150–7. doi: 10.2337/db07-0903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hiden U, Lassance L, Tabrizi NG, Miedl H, Tam-Amersdorfer C, Cetin I, Lang U, Desoye G. Fetal insulin and IGF-II contribute to gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM)-associated up-regulation of membrane-type matrix metalloproteinase 1 (MT1-MMP) in the human feto-placental endothelium. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:3613–21. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jager J, Gremeaux T, Cormont M, Le Marchand-Brustel Y, Tanti JF. Interleukin-1beta-induced insulin resistance in adipocytes through down-regulation of insulin receptor substrate-1 expression. Endocrinology. 2007;148:241–51. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jansson N, Greenwood SL, Johansson BR, Powell TL, Jansson T. Leptin stimulates the activity of the system A amino acid transporter in human placental villous fragments. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:1205–11. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones HN, Jansson T, Powell TL. Full-length adiponectin attenuates insulin signaling and inhibits insulin-stimulated amino Acid transport in human primary trophoblast cells. Diabetes. 2010;59:1161–70. doi: 10.2337/db09-0824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaplan B, Shohat M, Royburt M, Peleg D, Peled Y, Shohat B. Interleukin 1beta in serum of women with preterm uterine contractions. J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;17:444–5. doi: 10.1080/01443619750112394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kar M, Ghosh D, Sengupta J. Histochemical and morphological examination of proliferation and apoptosis in human first trimester villous trophoblast. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:2814–23. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kayali AG, Austin DA, Webster NJ. Stimulation of MAPK cascades by insulin and osmotic shock: lack of an involvement of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in glucose transport in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Diabetes. 2000;49:1783–93. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.11.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kliman HJ, Nestler JE, Sermasi E, Sanger JM, Strauss JF., 3rd Purification, characterization, and in vitro differentiation of cytotrophoblasts from human term placentae. Endocrinology. 1986;118:1567–82. doi: 10.1210/endo-118-4-1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kudo Y, Boyd CA. Human placental amino acid transporter genes: expression and function. Reproduction. 2002;124:593–600. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1240593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lager S, Powell TL. Regulation of Nutrient Transport across the Placenta. Journal of Pregnancy. 2012;2012:14. doi: 10.1155/2012/179827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lanoix D, St-Pierre J, Lacasse AA, Viau M, Lafond J, Vaillancourt C. Stability of reference proteins in human placenta: general protein stains are the benchmark. Placenta. 2012;33:151–6. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Larsen CM, Faulenbach M, Vaag A, Volund A, Ehses JA, Seifert B, Mandrup-Poulsen T, Donath MY. Interleukin-1-receptor antagonist in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1517–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laviola L, Perrini S, Belsanti G, Natalicchio A, Montrone C, Leonardini A, Vimercati A, Scioscia M, Selvaggi L, Giorgino R, Greco P, Giorgino F. Intrauterine growth restriction in humans is associated with abnormalities in placental insulin-like growth factor signaling. Endocrinology. 2005;146:1498–505. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leach L. Placental vascular dysfunction in diabetic pregnancies: intimations of fetal cardiovascular disease? Microcirculation. 2011;18:263–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2011.00091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee J, Pilch PF. The insulin receptor: structure, function, and signaling. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:C319–34. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.266.2.C319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee YH, Giraud J, Davis RJ, White MF. c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) mediates feedback inhibition of the insulin signaling cascade. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:2896–902. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208359200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li RH, Zhuang LZ. Study on reproductive endocrinology of human placenta--culture of highly purified cytotrophoblast cell in serum-free hormone supplemented medium. Sci China B. 1991;34:938–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Madan JC, Davis JM, Craig WY, Collins M, Allan W, Quinn R, Dammann O. Maternal obesity and markers of inflammation in pregnancy. Cytokine. 2009;47:61–4. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maedler K, Dharmadhikari G, Schumann DM, Storling J. Interleukin-1 beta targeted therapy for type 2 diabetes. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2009;9:1177–88. doi: 10.1517/14712590903136688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maedler K, Sergeev P, Ris F, Oberholzer J, Joller-Jemelka HI, Spinas GA, Kaiser N, Halban PA, Donath MY. Glucose-induced beta cell production of IL-1beta contributes to glucotoxicity in human pancreatic islets. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:851–60. doi: 10.1172/JCI15318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Magnusson-Olsson AL, Lager S, Jacobsson B, Jansson T, Powell TL. Effect of maternal triglycerides and free fatty acids on placental LPL in cultured primary trophoblast cells and in a case of maternal LPL deficiency. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293:E24–30. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00571.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mandl M, Haas J, Bischof P, Nohammer G, Desoye G. Serum-dependent effects of IGF-I and insulin on proliferation and invasion of human first trimester trophoblast cell models. Histochem Cell Biol. 2002;117:391–9. doi: 10.1007/s00418-002-0403-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morrish DW, Bhardwaj D, Dabbagh LK, Marusyk H, Siy O. Epidermal growth factor induces differentiation and secretion of human chorionic gonadotropin and placental lactogen in normal human placenta. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1987;65:1282–90. doi: 10.1210/jcem-65-6-1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morrish DW, Dakour J, Li H, Xiao J, Miller R, Sherburne R, Berdan RC, Guilbert LJ. In vitro cultured human term cytotrophoblast: a model for normal primary epithelial cells demonstrating a spontaneous differentiation programme that requires EGF for extensive development of syncytium. Placenta. 1997;18:577–85. doi: 10.1016/0143-4004(77)90013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Norman JE, Reynolds RM. The consequences of obesity and excess weight gain in pregnancy. Proc Nutr Soc. 2011;70:450–6. doi: 10.1017/S0029665111003077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pattillo RA, Gey GO. The establishment of a cell line of human hormone-synthesizing trophoblastic cells in vitro. Cancer Res. 1968;28:1231–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Perlman R, Barzilai D, Bick T, Hochberg Z. The effect of inhibitors on insulin regulation of hormone secretion by cultured human trophoblast. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1985;43:77–82. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(85)90044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ramirez VI, Gaccioli F, Jansson T, Powell T. Placental insulin resistance in women with high BMI: Insulin receptor expression and insulin signaling. Reproductive Sciences. 2012;19:307A. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ren SG, Braunstein GD. Insulin stimulates synthesis and release of human chorionic gonadotropin by choriocarcinoma cell lines. Endocrinology. 1991;128:1623–9. doi: 10.1210/endo-128-3-1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roberts KA, Riley SC, Reynolds RM, Barr S, Evans M, Statham A, Hor K, Jabbour HN, Norman JE, Denison FC. Placental structure and inflammation in pregnancies associated with obesity. Placenta. 2011;32:247–54. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2010.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Roos S, Lagerlof O, Wennergren M, Powell TL, Jansson T. Regulation of amino acid transporters by glucose and growth factors in cultured primary human trophoblast cells is mediated by mTOR signaling. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;297:C723–31. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00191.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rosario FJ, Kanai Y, Powell TL, Jansson T. Mammalian target of rapamycin signalling modulates amino acid uptake by regulating transporter cell surface abundance in primary human trophoblast cells. J Physiol. 2013;591:609–25. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.238014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rosario FJ, Schumacher MA, Jiang J, Kanai Y, Powell TL, Jansson T. Chronic maternal infusion of full-length adiponectin in pregnant mice down-regulates placental amino acid transporter activity and expression and decreases fetal growth. J Physiol. 2012;590:1495–509. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.226399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Street ME, Viani I, Ziveri MA, Volta C, Smerieri A, Bernasconi S. Impairment of insulin receptor signal transduction in placentas of intra-uterine growth-restricted newborns and its relationship with fetal growth. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;164:45–52. doi: 10.1530/EJE-10-0752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tanti JF, Jager J. Cellular mechanisms of insulin resistance: role of stress-regulated serine kinases and insulin receptor substrates (IRS) serine phosphorylation. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2009;9:753–62. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tanti JF, Ceppo F, Jager J, Berthou F. Implication of inflammatory signaling pathways in obesity-induced insulin resistance. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2012;3:181. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2012.00181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thongsong B, Subramanian RK, Ganapathy V, Prasad PD. Inhibition of amino acid transport system a by interleukin-1beta in trophoblasts. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2005;12:495–503. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.van Asseldonk EJ, Stienstra R, Koenen TB, Joosten LA, Netea MG, Tack CJ. Treatment with Anakinra improves disposition index but not insulin sensitivity in nondiabetic subjects with the metabolic syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:2119–26. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Van den Berghe G. How does blood glucose control with insulin save lives in intensive care? J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1187–95. doi: 10.1172/JCI23506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vandanmagsar B, Youm YH, Ravussin A, Galgani JE, Stadler K, Mynatt RL, Ravussin E, Stephens JM, Dixit VD. The NLRP3 inflammasome instigates obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance. Nat Med. 2011;17:179–88. doi: 10.1038/nm.2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zeck W, Widberg C, Maylin E, Desoye G, Lang U, McIntyre D, Prins J, Russell A. Regulation of placental growth hormone secretion in a human trophoblast model--the effects of hormones and adipokines. Pediatr Res. 2008;63:353–7. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000304935.19183.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhu MJ, Du M, Nathanielsz PW, Ford SP. Maternal obesity up-regulates inflammatory signaling pathways and enhances cytokine expression in the mid-gestation sheep placenta. Placenta. 2010;31:387–91. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trophoblast cells were identified by western blotting analysis of Cytokeratin-7 and Vimentin. Trophoblast cell cultures express Cytokeratin-7 protein (epithelial cell marker) but do not express Vimentin (mesenchymal cell marker). Total protein homogenates from term placental tissues was used as a positive control for both Cytokeratin-7 and Vimentin. Pl Hom, placental homogenate; PHT, primary human trophoblast cells.

Cell viability was analyzed after treatment with IL-1β (10 pg/ml) for 24 h. Cell viability measured using the 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) cell viability assay. PHT cells plated in triplicate in 96 well plates at 1 × 10−5 cells per well. At the end of treatment, 1 mg/ml of MTT reagent was added to each well for 4h at 37 °C, lysed with 10% SDS and absorbance read at 570 nm. Cell viability was presented as a percentage of vehicle-treated controls. N=3, IL-1β treatments were not significantly different controls. Cnt, control; IL-1β, interleukin-1β.