Abstract

BACKGROUND

Naltrexone (NTX) is under-utilized in clinical treatment settings because it’s efficacy is modest, it is not effective for all alcoholics and, when it is effective, a significant number of alcoholics fail to maintain initial treatment gains and subsequently relapse to heavy drinking. This has slowed acceptance of NTX by the treatment community and there is a clear need for additional treatments for alcoholism and alcohol use disorders. Given that NTX and prazosin can each reduce alcohol drinking in rats selectively bred for alcohol preference and high voluntary alcohol drinking (alcohol-preferring “P” rats), we tested whether a combination of NTX + prazosin is more effective in decreasing alcohol drinking than is either drug alone.

METHODS

P rats were given access to a 15% (v/v) alcohol solution for two hrs daily. Rats were fed NTX and prazosin, alone or in combination, prior to onset of the daily 2 hr alcohol access period for 4 weeks and the effect of drug treatment on alcohol and water intake was assessed.

RESULTS

During the first week of treatment neither a low dose of NTX, nor prazosin, was effective in decreasing alcohol intake when each drug was administered alone, but combining the two drugs in a single medication significantly reduced alcohol intake. The combination was as effective as was a higher dose of NTX. Using a low dose of NTX in combination with prazosin may reduce the potential for undesirable side effects early in treatment which, in turn, may improve patient compliance and result in a more successful outcome when NTX is used for treating alcoholism and alcohol use disorders.

CONCLUSIONS

Combining low dose NTX and prazosin in a single medication may be more useful than is either drug alone for treating both inpatient and outpatient alcoholics and heavy drinkers early in the treatment process.

Keywords: alcoholism treatment, genetic selection, naltrexone, prazosin

Alcoholism is the most prevalent and widespread of all addictive diseases and development of effective treatments is a high priority. Only three drugs have been approved by the FDA for the treatment of alcohol dependence in the United States: disulfiram (antabuse), acamprosate, and naltrexone (tradename Trexan or Revia). Although naltrexone (NTX) is more effective than is acamprosate (Anton et al., 2006), and compliance is far greater with NTX than with disulfiram (Anton et al., 2006; Fuller et al., 1986), NTX is under-utilized because its efficacy is modest (Froehlich et al., 2003; O’Malley and Froehlich, 2003), it is not effective for all alcoholics (Kranzler and Van Kirk, 2001; Oncken et al., 2001) and, when it is effective, a significant number of alcoholics fail to maintain initial treatment gains and subsequently relapse to heavy drinking (Anton et al., 2006; Garbutt et al., 2005; Krystal et al., 2001). These facts have slowed acceptance of NTX by the treatment community (O’Malley and Froehlich, 2003) and illustrate the importance of finding additional medications for the treatment of alcoholism and alcohol abuse.

One of the strongest positively reinforcing effects of alcohol is induction of euphoria (“high”) and feelings of well being (Gilman et al., 2008). Naltrexone, the prototypical opioid receptor antagonist, reduces the reinforcing or euphoriant effects of alcohol by blocking opioid receptors in the brain (Froehlich et al., 2003; Froehlich and Li, 1994; Mitchell et al., 2012; O’Malley and Froehlich, 2003; O’Malley et al., 1996; Volpicelli et al., 1995). One of the strongest negatively reinforcing effects of alcohol is anxiety reduction. More than 50% of patients with anxiety, or major depression, abuse alcohol in an effort to self-medicate since alcohol has both anxiolytic and sympatho-suppressive properties (Kushner et al., 2000; Spanagel et al., 1995). Activation of the noradrenergic system accompanies anxiety and hyperexcitability (Aston-Jones and Cohen, 2005) and agents that reduce central noradrenergic signaling (anxiolytic agents) may substitute for the anxiolytic effects of alcohol and thereby reduce motivation to drink and alcohol intake.

We recently began a research program to determine which agents that decrease central noradrenergic signaling are effective in decreasing alcohol drinking in a rodent model of alcoholism. One especially promising agent is prazosin, an α1-adrenergic receptor antagonist. In preclinical studies prazosin decreased alcohol drinking/self-administration in a variety of experimental conditions: a) in rats selectively bred for high voluntary alcohol drinking (alcohol preferring or “P” rats) during both acute (Rasmussen et al., 2009a,b) and prolonged (Froehlich et al., 2013) treatment, b) in P rats when access to alcohol was reintroduced following periods of alcohol deprivation (Rasmussen et al., 2009a) and c) in alcohol-dependent Wistar rats during acute alcohol withdrawal (Walker et al., 2008). In humans, prazosin has been used to treat post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) where it reduces hyperarousal, overall PTSD severity (Raskind et al., 2003) and, parenthetically, alcohol drinking (Raskind et al., 2009). Recently, prazosin was found to decrease relapse drinking in alcohol-dependent men without PTSD (Simpson et al., 2009) and a preliminary study reports that prazosin decreases stress- and cue-induced alcohol craving in alcohol-dependent individuals (Fox et al., 2011).

Both NTX and prazosin, when given alone, can decrease alcohol drinking in rodents and humans and both are safe, orally active, well-characterized, inexpensive, FDA-approved for human use and well-tolerated when administered in clinically relevant doses. Therefore, combining these two classes of drugs may be beneficial in treating alcoholism and alcohol use disorders. Using an animal model of alcoholism, we assessed whether combining NTX and prazosin in a single medication was more effective in decreasing alcohol drinking than was either drug alone. NTX and prazosin were administered orally for a month in order to determine their efficacy, alone or in combination, over the course of prolonged treatment. We hypothesized that combining NTX + prazosin in a single medication will represent a new clinically useful option for treating alcoholism and alcohol use disorders.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

In 1974, Drs. Li and Lumeng began a selective breeding program for high and low alcohol drinking which resulted in the derivation of two rat lines: the alcohol-preferring (P) and non-preferring (NP) lines (Li et al., 1979). The P and NP lines were developed through mass selection from a foundation stock of outbred Wistar rats from the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research. Rats were tested for alcohol preference during 4 days of access to alcohol alone followed by 4 weeks of free-choice between a 10% (v/v) alcohol solution and water with food freely available. Rats were selected for breeding based on their average alcohol intake during the 4 weeks of free-choice between alcohol and water. Rats selected for breeding in the P line were those that consumed alcohol in excess of 5 g alcohol/kg BW/day and demonstrated a greater than 2:1 preference ratio for alcohol over water. Rats selected for breeding in the NP line were those that consumed less than 1.5 g alcohol/kg BW/day and did not exceed an alcohol to water preference ration of 0.2:1.0. Rats of the P line have been extensively characterized both behaviorally and physiologically (Froehlich, 2010; Froehlich and Li, 1991; Li et al., 1988; 1993) and have been found to meet all of the criteria of an animal model of alcoholism (Cicero, 1979). P rats are selectively bred in the Indiana University Alcohol Research Resource Center using “intensive selection” where they are tested for alcohol preference in every generation or using “relaxed selection” where they are tested for alcohol preference every 3-4 generations. The rats in the current study were from the 71st generation of selective breeding for alcohol preference. Generation 71 was not preference tested but generations 70 and 73 were tested and the average alcohol intake was 8.31 g/kg BW/day and 6.85 g/kg BW/day, respectively. Prior to weaning, the pups are housed with their dam at a density of 12 rats per cage. After weaning and up to 200 g BW they are housed with 4 males per cage and 5 females per cage. Beyond 200 g BW they are housed with 2 males per cage and 3 females per cage until delivery to the investigator.

Fifty nine adult male alcohol-preferring (P) rats from the 71st generation of selective breeding for alcohol preference were purchased from the Indiana University Alcohol Research Resource Center, and were delivered at 50-58 days of age (182-286 g BW). Only males were used in order to avoid the potential confound of drug effects with day of the estrous cycle in female rats. The rats were individually housed in stainless steel hanging cages in an isolated vivarium with controlled temperature (21±1 °C) and a 12 h light/dark cycle (lights off at 1000 h). Standard rodent chow (Laboratory Rodent Diet #7001, Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI) and water were available ad libitum throughout the study. All subjects were acclimated to individual housing for two weeks prior to introduction of a free-choice between alcohol and water. All experimental procedures were approved by the Indiana University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conducted in strict compliance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Experimental Design

Prior to drug treatment all rats were given scheduled access to alcohol daily using a stepwise procedure, as described below, to reach a daily 2-hr alcohol (15% v/v) access period. The effect of NTX, prazosin, or a combination of both, on alcohol drinking was assessed in six separate groups of rats treated daily for 4 weeks with vehicle, prazosin alone (2.0 mg/kg), NTX alone (10 or 20 mg/kg), or prazosin (2.0) + NTX (10.0 or 20.0 mg/kg). All drugs were administered (fed) in flavored gelatin at 45 minutes prior to onset of the daily 2 hr alcohol access period for 4 weeks

Alcohol Solution

The alcohol solution was prepared by diluting 95% alcohol with distilled, deionized water to make a 15% (v/v) solution. Alcohol (15% v/v) and water were presented in calibrated glass drinking tubes and daily fluid intakes were recorded to the nearest ml. Alcohol intake was converted from ml alcohol/kg body weight (BW) to g alcohol/kg BW.

Alcohol Drinking Induction

Paradigms involving scheduled access to alcohol are often used to assess the effects of drugs on alcohol intake in P rats (Froehlich et al., 1990; 2013; Rasmussen et al., 2009a,b). Scheduling access to alcohol for a few hours a day allows for the effect of a drug with a relatively short half-life to be easily assessed. In order to maximize alcohol intake during a two hour daily alcohol access period, access to alcohol was reduced using a “step down” procedure as previously described (Froehlich et al., 2013; Rasmussen et al., 2009a,b). Prior to assigning rats to treatment groups, rats were given 24-hr access to food and water and access to alcohol (15% v/v alcohol solution) for 8 hrs/day, constituting a daily 8 hr two-bottle free-choice between alcohol and water, for 2 weeks, followed by a reduction in access to alcohol to 4 hrs/day (daily 4 hr two-bottle free-choice) for two weeks, followed by a further reduction in alcohol access to 2 hrs/day (daily 2 hr two-bottle free-choice) for the duration of the study. Alcohol was available from 1000 hrs (onset of the dark cycle) to 1200 hrs daily 5 days a week (Mon-Fri). Alcohol intake and water intake were recorded daily at the end of the 2-hour alcohol access period and body weight was recorded twice weekly.

Drug Preparation and Delivery

Prazosin hydrochloride and naltrexone hydrochloride (both from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were incorporated into flavored star-shaped pieces of gelatin that were voluntarily consumed by the rats. Prazosin and NTX, alone or in combination, were dissolved in deionized distilled water and added to a sweetened gelatin solution. The solution was comprised of berry flavored Jell-O, gelatin, dextrose, sodium saccharin and Magnasweet in distilled, deionized water. Prazosin or NTX, expressed as free base masses, were added to the gelatin solution to provide the following doses: 2.0 mg prazosin/3.0 ml solution/kg BW, 10.0 mg NTX/3.0 ml solution/kg BW, 2.0 mg prazosin + 10.0 mg NTX/3.0 ml solution/kg BW, 20.0 mg NTX/3.0 ml solution/kg BW, and 2.0 mg prazosin + 20.0 mg NTX/3.0 ml solution/kg BW. The gelatin solution, containing drug or no drug (vehicle), was aliquoted into star shaped molds, one per rat per day, with the volume of each aliquot determined by the body weight of the rat, as previously described (Froehlich et al., 2013). NTX and prazosin, alone or in combination, were fed to the rats once each day in the small (approximately 1.8 gram) piece of gelatin inserted through a hole in the front of the cage. The rats consistently ate the gelatin within 1 minute. Cages were checked to confirm that no pieces of gelatin were dropped. If they were, which was rare, they were refed to the rat. Gelatin was fed each day at 45 min prior to onset of the daily 2-hr alcohol access period because the half-lives of NTX and prazosin are relatively short. The half-life of NTX in the rat is 4 ±0.9 hrs (Hussain et al., 1987). The half-life of prazosin in the rat has not been determined but is about 3 hrs in the human (Goodman and Gilman, 2006). In an earlier study (data not shown), we found that consumption of the flavored gelatin with no drug (vehicle) at 45 min prior to daily 2 hr access to alcohol did not alter alcohol intake. Specifically, average daily 2 hr alcohol intake during the 5 days prior to consumption of vehicle gelatin was 1.8 g/kg BW (N=64 adult male P rats) and average daily 2 hr alcohol intake in these same rats during 5 days of consumption of vehicle gelatin was 1.7 g/kg BW. In the current study, vehicle gelatin was fed to all rats each day for one week prior to initiation of drug treatment. We have previously used this oral drug delivery approach successfully for the prolonged administration of prazosin (Froehlich et al., 2013). It can be used for any drug that is water soluble and orally active as are NTX and prazosin (Froehlich et al., 2013; Liles et al., 1997).

Assigning Rats to Treatment Groups

Rats were assigned to groups in a manner that ensured that the groups were matched on alcohol intake prior to drug administration (Froehlich et al., 2013; Rasmussen et al., 2009a,b). Daily alcohol intake for each rat was averaged over 3-5 consecutive days prior to onset of drug treatment in order to minimize the effect of minor daily fluctuations in intake. Rats were then ranked based on their average daily alcohol intake during the 2-hour alcohol access period. The top alcohol drinkers were randomly assigned to the drug treatment groups, followed by the next highest drinkers, until all groups were complete.

Data Analyses

Differences between treatment groups were tested for significance using a 1- or 2- way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures on day or week followed, when justified, by pairwise multiple comparisons using Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) test. Data are presented as mean ± S.E. Occasional missing observations were estimated using the mean of alcohol (or water) intake on the day before and the day after the day when the missing observation occurred.

Experimental Design

Experiment 1: Four Weeks of Drug Treatment

After completion of the alcohol “step-down” procedure and 8 weeks of access to alcohol for 2 hrs a day, rats were fed gelatin containing NTX in a dose of 0, 10.0 or 20.0 mg/kg BW, or prazosin in a dose of 0, or 2.0 mg/kg BW (N=10), or a combination of NTX (10 or 20 mg/kg BW) + prazosin (2.0 mg/kg BW) (N=10 and N=7 respectively) once each day for 5 consecutive days/week for 4 weeks.

Experiment 2: Test of Drug Additivity

Following completion of Experiment 1, rats were given 3 weeks without drug to eliminate potential effects of prior drug treatment. During this time rats were fed gelatin without drug (vehicle) daily at 45 min prior to onset of the 2-hr alcohol access period, and alcohol and water intake were recorded daily. Alcohol intake returned to pre-drug baseline levels in all groups prior to the initiation of Experiment 2. Rats were reassigned to treatment groups based on their mean 2 hr alcohol intake over 3 consecutive days. Rats were fed vehicle gelatin or gelatin containing NTX alone, prazosin alone, or NTX + prazosin at 45 min prior to onset of the daily 2-hr alcohol access period for 4 consecutive days. The drug doses were NTX (10.0 mg/kg BW), prazosin (2.0 mg/kg BW), NTX (10.0 mg/kg BW) + prazosin (2.0 mg/kg BW), NTX (7.5 mg/kg BW) + prazosin (0.5 mg/kg BW) which represents 75% of the dose of NTX alone + 25% of the dose of prazosin alone, NTX (5.0 mg/kg BW) + prazosin (1.0 mg/kg BW) which represents 50% of the dose of NTX alone + 50% of the dose of prazosin alone, or NTX (2.5 mg/kg BW) + prazosin (1.5 mg/kg BW) which represents 25% of the dose of NTX alone + 75% of the dose of prazosin alone. Drug effects on 2 hour alcohol and water intake were assessed as described in Experiment 1.

RESULTS

Alcohol Drinking Induction

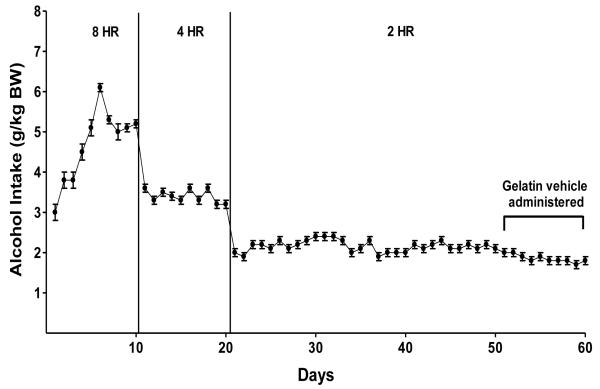

Prior to assigning rats to treatment groups, alcohol access was reduced in increments from 24 hrs/day to 2 hrs/day over the course of 4 weeks. This “step down” procedure produces stable alcohol intake of approximately 2.0 g/kg alcohol/2 hrs in P rats (Froehlich et al., 2013; Rasmussen et al., 2009a,b) (Figure 1). This level of alcohol intake produces physiologically relevant blood alcohol concentrations (BACs).

Figure 1.

Alcohol intake in P rats given 24-hr access to food and water and scheduled access to alcohol (15% v/v) for 8hrs/day for 2 weeks, followed by a reduction in access to alcohol to 4hrs/day for 2 weeks, followed by a reduction in access to alcohol to 2hr/day for the duration of the study. Scheduled alcohol access was 5 days/week (Monday-Friday).

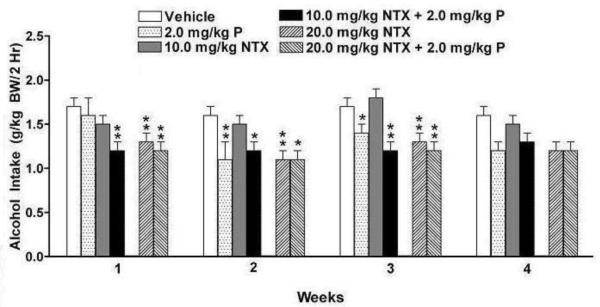

Four Weeks of Drug Treatment

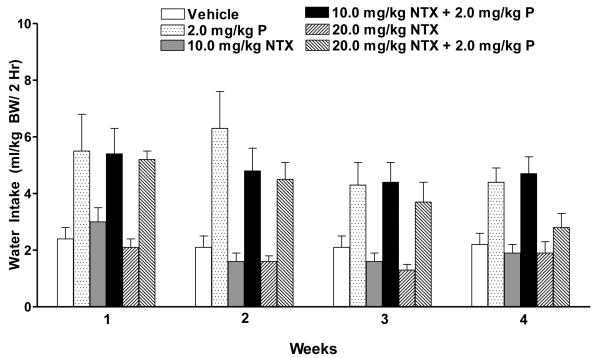

Weekly alcohol intake was averaged for each rat and analyzed over 4 weeks with two-way ANOVA (treatment X week with repeated measures on week). There were significant effects of treatment [F (5, 52) = 4.72, p<0.01] and week [F (3, 156) = 9.05, p<0.001] and a treatment X week interaction [F (15,156) = 1.92, p<0.05] (Figure 2). Fisher’s LSD post hoc analysis revealed that, during week one, neither a low dose of NTX (10.0 mg/kg BW) alone nor prazosin alone reduced alcohol drinking compared to vehicle. However, combining the ineffective low dose of NTX with the ineffective dose of prazosin produced a combination that was effective in decreasing alcohol intake (p<0.01). In fact, it was as effective as was a higher dose of NTX (20.0 mg/kg BW) (p<0.01) when administered either alone or in combination with prazosin (p<0.01). During week two, prazosin became effective in reducing alcohol drinking relative to vehicle (p<0.01), but low dose NTX did not. Prazosin, in combination with low dose NTX, reduced alcohol intake (p<0.05) as did a higher dose of NTX (20.0 mg/kg BW) (p<0.01) administered alone or in combination with prazosin (p<0.05). During week three, prazosin reduced alcohol drinking relative to vehicle (p<0.05), but low dose NTX did not. Prazosin, in combination with low dose NTX, was as effective in reducing alcohol drinking (p<0.001) as was a higher dose of NTX (20.0 mg/kg BW) (p<0.01) alone or in combination with prazosin (p<0.01). Although there were no significant treatment effects in week 4, a strong trend was found (p=0.074) and the pattern of drinking was similar to that seen in weeks 2 and 3. Weekly water intake was likewise averaged for each rat and analyzed with two-way ANOVA (treatment X week with repeated measures on week). There were significant effects of treatment [F (5, 52) = 9.15, p<0.001] and week [F (3, 156) = 8.03, p<0.001] but no significant treatment X week interaction (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Effect of oral treatment with prazosin alone (2.0 mg/kg BW, N=10), NTX alone (10.0 or 20 mg/kg BW, N=10), or prazosin (2.0 mg/kg BW) + NTX (10.0 or 20.0 mg/kg BW; N=10 and N=7 respectively), or vehicle (N=11) on average alcohol intake in P rats during each week of drug treatment. Alcohol intake was averaged for each rat across each week. Each bar represents the mean ± S.E. *p<0.05 vs vehicle, **p<0.01 vs vehicle.

Figure 3.

Effect of oral treatment with prazosin alone (2.0 mg/kg BW, N=10), or NTX alone (10.0 or 20.0 mg/kg BW, N=10), or prazosin (2.0 mg/kg BW, N=7) + NTX (10.0 or 20 mg/kg BW; N=10 and N=7 respectively), or vehicle (N=11) on average water intake in P rats during each week of drug treatment. Water intake was averaged for each rat across each week

Data were also analyzed across days because number of total treatment days when a drug effect is seen is a criterion of drug efficacy often used in clinical studies. Alcohol intake on individual days of drug treatment was analyzed using a two-way ANOVA (treatment X day with repeated measures on day). There were significant effects of treatment [F (5, 52) = 4.52, p<0.01] and day [F (19, 988) = 7.93, p<0.001] and a treatment by day interaction [F (95, 988) = 1.51, p<0.01]. The effect of drug treatment on each day was assessed with a one-way ANOVA for each day. During the first 15 days of treatment (when significant drug effects were observed in the analyses of weekly averages), low dose NTX (10.0 mg/kg BW) suppressed alcohol intake on only 1 of the 15 days of treatment and prazosin (2.0 mg/kg BW) suppressed alcohol intake on 5 of the 15 days. In contrast, the combination of low dose NTX (10.0 mg/kg BW) + prazosin (2.0 mg/kg BW) suppressed alcohol intake on 12 of the 15 days of treatment.

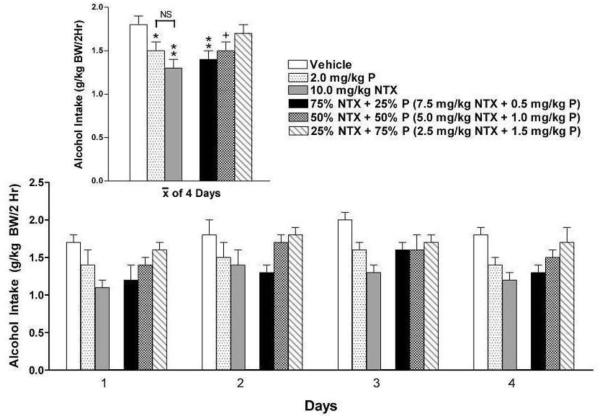

Test of Drug Additivity

The fact that the combination of low dose NTX + prazosin was more effective than was either drug alone raised a question regarding the nature of the relationship between these two drugs. The effect of two drugs is said to be additive if the response to a dose of the two in combination does not change when a portion of one is removed from the mixture and replaced by an equipotent portion of the other (Laska et al., 1994). If such a substitution increases the response (eg: a larger decrease in alcohol drinking), the relationship between the two drugs is synergistic. To determine the relationship between low dose NTX and prazosin, rats were treated for 4 consecutive days with equipotent doses of prazosin (2.0 mg/kg BW) alone and NTX (10.0 mg/kg BW) alone, or in three different drug dose ratios (Figure 4). Treatment for 5 days was intended (as in experiment 1), but was interrupted on the 5th day.

Figure 4.

Effect of naltrexone (10.0 mg/kg BW, N=10) or prazosin (2.0 mg/kg BW; N=10) or 75% NTX + 25% P (N=10), or 50% NTX + 50% P (N=10), or 25% NTX + 75% P (N=10), or vehicle (N=9) on alcohol intake in P rats during 4 consecutive days of drug treatment. Each bar represents the mean ± S.E. +p=0.09 vs vehicle, *p<0.05 vs vehicle; **p<0.01 vs vehicle.

A 2-way ANOVA (treatment X day with repeated measures on day) revealed significant effects of treatment [F (5, 53) = 3.20, p<0.05] and day [F (3, 159) = 8.23, p<0.001) but no treatment X day interaction. Fisher’s LSD post hoc analysis revealed that both prazosin alone and NTX alone decreased alcohol intake compared with vehicle (p<0.05 and p<0.01 respectively). The decrease in alcohol intake did not change appreciably when 25% of NTX or 50% of NTX was replaced with equipotent portions of prazosin (75% NTX+ 25% P, p<0.01 vs vehicle; 50% NTX + 50% P, p=0.09 vs vehicle), suggesting that the relationship between the two drugs is additive. At a very low ratio of NTX to P (25% NTX + 75% P) the decrease in alcohol drinking disappeared, suggesting that threshold doses of each drug may be needed in order to suppress alcohol drinking. The fact that prazosin (2.0 mg/kg BW) and low dose of NTX (10.0mg/kg BW) did not reduce alcohol intake during the first 4 days of treatment in experiment 1, but did so after 3 weeks of no drug treatment in experiment 2, suggests that an increase in sensitivity to drug effects may have occurred.

DISCUSSION

Opioid antagonists were first shown to decrease alcohol drinking in rats selectively bred for high voluntary alcohol intake (Froehlich et al., 1990; Froehlich and Li, 1993; 1994; Gilpin et al., 2008; Krishnan-Sarin et al., 1995; 1998) and the results of these preclinical studies led to clinical trials on the effect of NTX on alcohol drinking in alcoholics and heavy drinkers (Anton et al., 2006; Pettinati et al., 2006). Despite the clear benefit of NTX for many alcoholics, NTX is not effective for all alcoholics (Kranzler and Van Kirk, 2001; Krystal et al., 2001). We postulated that maximizing the clinical utility of NTX might require combining NTX with another type of medication that acts via a nonopioid pathway.

Based on our prior work, we predicted that combining a low dose of NTX with the α1 –adrenergic receptor antagonist, prazosin, in a single medication would be more effective in reducing alcohol drinking than would either drug alone. The results of the current study support this view. During week one of treatment, neither the lower dose of NTX nor prazosin, when given alone, decreased alcohol intake. However, combining an ineffective dose of NTX with an ineffective dose of prazosin resulted in a medication that decreased alcohol drinking during week one. During the second week of treatment, prazosin alone became effective in decreasing alcohol drinking, but low dose NTX alone did not. In contrast, the combination of prazosin + low dose NTX significantly reduced alcohol drinking during the first week of treatment and continued to reduce alcohol intake throughout 3 weeks of treatment. This drug combination was as effective in reducing drinking as was a higher dose of NTX (20.0 mg/kg BW).

There are several benefits of combining drugs for the treatment of alcoholism and alcohol abuse. First, people drink alcohol for different reasons, such as to induce positive feelings, reduce anxiety, or blunt memory. A medication that targets one action of alcohol may not be as effective as a combined medication that targets more than one action. Different combinations of medications could be used to treat subpopulations of alcoholics and heavy drinkers who drink for different reasons. Second, enhanced effectiveness may be achieved at lower doses when drugs are combined, which can reduce potential side effects associated with each drug. This may be particulary useful with regard to NTX, which is normally well tolerated (Croop et al., 1997) but has produced dysphoria, malaise, and depression-like symptoms in some individuals (Hollister et al., 1981; Malcolm et al., 1987; Oncken et al., 2001). Third, combining drugs may be effective for a subset of alcoholics who are not responsive to either drug alone.

The doses of NTX used in the current study (10.0 and 20.0 mg/kg BW) are higher than those commonly used to decrease alcohol drinking in rats when NTX is delivered non-orally (Gilpin et al., 2008; Gonzales and Weiss, 1998; Le et al., 1999). This is because the bioavailability of NTX is low when it is administered orally (Hussain et al; 1987) and hence an upward adjustment in dose is required when moving from a non-oral to an oral route. NTX has an oral bioavailability of only 1% in rats (Hussain et al., 1987) which is much lower than the level of bioavailability in humans (5-40%) (Goodman and Gilman, 2006). The low oral potency of NTX in rats is due to rapid first pass metabolism, rather than to poor absorption (Shepard et al., 1985). For instance, 20 mg NTX/kg, when delivered via gavage in rats, produces a peak plasma level of only 15 ng NTX/ml during the first hour and plasma levels fall by half in the second hour (Hussain, et al 1987). In contrast, when 2.2 mg NTX/kg (1/10 the dose delivered orally) was injected i.v.(via cardiac puncture) it produces a peak plasma level of NTX in the first hour of approximately 300 ng NTX/ml, or 20 times the peak level seen following oral administration of 10 times the dose (Hussain et al., 1987). Prazosin, on the other hand, is well-absorbed after oral administration and bioavailability is high, about 70% (Goodman and Gilman, 2006). Hence, prazosin doses that are effective when administered IP (Rasmussen et al., 2009a,b) are also effective when administered orally (Froehlich et al., 2013). We are not aware of any report of an interaction between NTX and prazosin that would increase side effects of either drug in rodents or humans.

Neither NTX nor prazosin, alone or in combination, eliminated alcohol drinking in P rats. Instead, these drugs reduced alcohol drinking. Complete “abstinence” in rats would not be expected since rats lack the psychosocial factors (counseling, social pressure, network support) that contribute significantly to abstinence in humans. The fact that naltrexone and prazosin reduce alcohol drinking without the contribution of these psychosocial factors suggests that these drugs may be even more effective for people who are motivated to reduce their drinking, such as drinkers who voluntarily seek treatment.

The prazosin-induced decrease in alcohol intake is not due to motor impairment or induction of generalized nausea or malaise since prazosin did not decrease water or food intake. Instead, prazosin increased water intake, an effect that we have previously seen (Froehlich et al., 2013; Rasmussen et al., 2009a,b) as have other investigators (Auriac et al., 1983; Oryan et al., 2003; Osborn et al., 1993) and which occurs in response to many drugs that reduce blood pressure (Stocker et al., 2001).

Using number of effective days as a criterion of drug efficacy, the combination of low dose NTX + prazosin was more effective in decreasing alcohol intake (12/15 treatment days) than was NTX alone (1/15 treatment days) or prazosin alone (5/15 treatment days). The fact that combining a low dose of NTX with prazosin was more effective in decreasing alcohol drinking than was either drug alone raised a question regarding the nature of the interaction between NTX and prazosin. Experiment 2 was designed to determine whether the relationship between NTX and prazosin is additive or synergistic (Tallarida et al., 1997). There are various ways to assess drug additivity and synergy but the majority require that the effect of combining two drugs be compared to the effect of each drug alone (Laska et al., 1994; Tallarida, 2001). Two drugs are said to be additive when combining equally effective doses of the two drugs (A and B) produces an effect that is equal to that obtained by doubling the dose of either drug alone (2A or 2B) (Niv et al., 1995; Poch and Holzmann 1980; Trendelenburg,1962). Stated another way, the effect of two drugs are additive if the effect of the two drugs in combination does not change when a portion of one drug is removed from the mixture and replaced by an equipotent portion of the other drug (Laska et al., 1994). If the substitution increases the effect, the drugs are said to be synergistic (Niv et al., 1995). Using the drug substitution approach, NTX and prazosin were found to act additively to decrease alcohol intake in P rats.

The fact that the combination of NTX+prazosin is effective in the first week of treatment is important for both inpatients and outpatients for whom the goal is to reduce drinking. Inpatients are usually instructed to remain abstinent for 4 days before starting drug treatment and alcohol craving is often high during this time (personal communication, Dr. Tim Kelley, Medical Director, Fairbanks Alcohol and Drug Treatment Center, 2012), so a rapidly acting medication may help to prevent relapse in these patients. For outpatients, increased drug effectiveness is likely to promote drug compliance because an immediate positive outcome with the drug reinforces the decision to continue with the treatment regimen.

In summary, the results demonstrate that NTX and prazosin act additively to reduce alcohol drinking in a rodent model of alcoholism. During the first week of treatment, when relapse vulnerability is high, a low dose of NTX + prazosin was as effective in decreasing alcohol drinking as was a higher dose of NTX. Lowering the dose of NTX early in treatment may reduce the possibility of undesirable side effects which, in turn, may improve patient compliance and clinical outcome.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. Ting-Kai Li and the Indiana Alcohol Research Center for supplying the selectively bred rats used in this study. This work was supported by NIH Grants AA018604 (JCF and DDR), AA07611 (JCF) and AA13881 (DDR). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism or the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, Cisler RA, Couper D, Donovan DM, Gastfriend DR, Hosking JD, Johnson BA, LoCastro JS, Longabaugh R, Mason BJ, Mattson ME, Miller WR, Pettinati HM, Randall CL, Swift R, Weiss RD, Williams LD, Zweben A. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence. The COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2003–2017. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Cohen JD. An integrative theory of locus coeruleus-norepinephrine function: Adaptive gain and optimal performance. Ann Rev Neurosci. 2005;28:403–450. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auriac A, Azam J, Dumas JC, Roux G, Montastruc JL. Role of alpha 1 adrenergic receptors in water balance in the rat. J Pharmacol. 1983;14:351–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicero TJ. A critique of animal analogues of alcoholism. In: Majchrowicz E, Noble EP, editors. Biochemistry and Pharmacology of Ethanol. Vol. 2. Plenum Press; New York: 1979. pp. 533–560. [Google Scholar]

- Croop RS, Faulkner EB, Labriola DF. The safety profile of naltrexone in the treatment of alcoholism. Results from a multicenter usage study. The naltrexone usage study group. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:1130–1135. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830240090013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox HC, Anderson GM, Tuit K, Hansen J, Kimmerling A, Siedlarz KM, Morgan PT, Sinha R. Prazosin effects on stress- and cue-induced craving and stress response in alcohol-dependent individuals: preliminary findings. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;36:351–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01628.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froehlich JC. What aspects of human alcohol use disorders can be modeled using selectively bred rat lines? Substance Use and Misuse. 2010;45:1727–1741. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2010.482424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froehlich JC, Harts J, Lumeng L, Li TK. Naloxone attenuates voluntary ethanol intake in rats selectively bred for high ethanol preference. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1990;35:385–390. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(90)90174-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froehlich JC, Hausauer BJ, Federoff DL, Fischer SM, Rasmussen DD. Prazosin reduces alcohol drinking throughout prolonged treatment and blocks the initiation of drinking in rats selectively bred for high alcohol intake. Alcohol: Clin Exp Res. 2013 doi: 10.1111/acer.12116. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froehlich JC, Li TK. Opioid peptides. In: Galanter M, editor. Recent Developments in Alcoholism. Volume 11: Ten Years of Progress. Plenum Publishing Co; New York: 1993. pp. 187–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froehlich JC, Li TK. Animal models for the study of alcoholism: Utility of selected lines. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 1991;10:61–71. doi: 10.1300/J069v10n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froehlich JC, Li TK. Opioid involvement in alcohol drinking. Annals of the NY Acad of Sci. 1994;739:156–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb19817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froehlich J, O’Malley S, Hyytiä P, Davidson D, Farren C. Preclinical and clinical studies on naltrexone: what have they taught each other? Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:533–539. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000057943.57330.AB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller RK, Branchey L, Brightwell DR, Derman RM, Emrick CD, Iber FL, James KE, Lacoursiere RB, Lee KK, Lowenstam I, Maany I, Neiderhiser D, Nocks JJ, Shaw S. Disulfiram treatment of alcoholism: a veterans administration cooperative study. JAMA. 1986;256:1449–1455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbutt JC, Kranzler HR, O’Malley SS, Gastfriend DR, Pettinati HM, Silverman BL, Loewy JW, Ehrich EW, Vivitrex Study Group Efficacy and tolerability of long-acting injectable naltrexone for alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:1617–1625. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.13.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman JM, Ramchandani VA, Davis MB, Bjork JM, Hommer DW. Why we like to drink: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study of the rewarding and anxiolytic effects of alcohol. J Neurosci. 2008;28:4583–4591. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0086-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilpin NW, Richardson HN, Koob GF. Effects of CRF1-receptor and opioid-receptor antagonists on dependence-induced increases in alcohol drinking by alcohol-preferring (P) rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:1535–1542. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00745.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales RA, Weiss F. Suppression of ethanol-reinforced behavior by naltrexone is associated with attenuation of the ethanol-induced increase in dialysate dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci. 1998;18:10663–10671. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-24-10663.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman LS, Gilman A. In: The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 11th Edition Brunton LL, Lazo JS, Parker KL, editors. McGraw-Hill; Illinois: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hollister LE, Johnson K, Boukhabza D, Gillespie HK. Aversive effects of naltrexone in subjects not dependent on opiates. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1981;8:37–41. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(81)90084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain MA, Aungst BJ, Kearney A, Shefter E. Buccal and oral bioavailability of naloxone and naltrexone in rats. Int J Pharm. 1987;36:127–130. [Google Scholar]

- Kranzler HR, Van Kirk J. Efficacy of naltrexone and acamprosate for alcoholism: a meta-analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1335–1341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan-Sarin S, Portoghese PS, Li TK, Froehlich JC. The delta2 opioid receptor antagonist naltriben selectively attenuates alcohol intake in rats bred for alcohol preference. Pharm Biochem Behav. 1995;52:153–159. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)00080-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan-Sarin S, Wand GS, Li XW, Portoghese PS, Froehlich JC. Effect of mu opioid receptor blockade on alcohol intake in rats bred for high alcohol drinking. Pharm Biochem Behav. 1998;59:627–635. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(97)00474-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krystal JH, Cramer JA, Krol WF, Kirk GF, Rosenheck RA, Veterans Affairs Naltrexone Cooperative Study 425 Group Naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence. New England J of Med. 2001;345:1734–1739. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner MG, Abrams K, Borchardt C. The relationship between anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorders: A review of major perspectives and findings. Clin Psychol Rev. 2000;20:149–71. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laska EM, Meisner M, Siegel C. Simple designs and model-free tests for synergy. Biometrics. 1994;50:834–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le AD, Poulos XC, Harding S, Watchus J, Juzytsch W, Shaham Y. Effects of naltrexone and fluoxetine on alcohol self-administration and reinstatement of alcohol seeking induced by priming injections of alcohol and exposure to stress. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21:435–444. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00024-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li TK, Lumeng L, Doolittle DP. Selective breeding for alcohol preference and associated responses. Behav Gen. 1993;23:163–170. doi: 10.1007/BF01067421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li TK, Lumeng L, Doolittle DP, McBride WJ, Murphy JM, Froehlich JC, Morzorati S. Behavioral and neurochemical associations of alcohol seeking behavior. Excerpta Medica International Congress Series. 1988;805:435–438. [Google Scholar]

- Li TK, Lumeng L, McBride WJ, Waller MS. Progress toward a voluntary oral consumption model of alcoholism. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1979;4:45–60. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(79)90040-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liles JH, Flecknell PA, Roughan J, Cruz-Madorran I. Influence of oral buprenorphine, oral naltrexone or morphine on the effects of laparotomy in the rat. Lab Anim. 1997;32:149–61. doi: 10.1258/002367798780600025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malcolm R, O’Neil PM, Von JM, Dickerson PC. Naltrexone and dysphoria: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry. 1987;22:710–716. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(87)90202-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JM, O’Neil JP, Janabi M, Marks SM, Jagust WJ, Fields HL. Alcohol consumption induces endogenous opioid release in the human orbitofrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:116ra6. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niv D, Nemirovsky A, Rudick V, Geller E, Urca G. Antinociception induced by simultaneous intrathecal and intraperitoneal administration of low doses of morphine. Anesth Analg. 1995;80:886–889. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199505000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley SS, Froehlich JC. Advances in the use of naltrexone: an integration of preclinical and clinical findings. In: Galanter M, editor. Recent Developments in Alcoholism XVI: Research on Alcoholism Treatment. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; New York: 2003. pp. 217–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley SS, Jaffe AJ, Rode S, Rounsaville BJ. Experience of a “slip” among alcoholics treated with naltrexone or placebo. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:281–283. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.2.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oncken C, Van Kirk J, Kranzler HR. Adverse effects of oral naltrexone: Analysis of data from two clinical trials. Psychopharmacology. 2001;154:397–402. doi: 10.1007/s002130000666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oryan S, Eidi M, Eidi A, Kohanrooz B. Effects of α1-adrenoceptors and muscarinic cholinoceptors on water intake in rats. European J Pharmacol. 2003;477:123–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn JW, Provo BJ, Montana JS, III, Trostel KA. Salt-sensitive hypertension caused by long-term α-adrenergic blockade in the rat. Hypertension. 1993;21:995–999. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.21.6.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettinati HM, O’Brien CP, Rabinowitz AR, Wortman SP, Oslin DW, Kampman KM, Dackis CA. The status of naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence: specific effects on heavy drinking. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;26:610–625. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000245566.52401.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pöch G, Holzmann S. Quantitative estimation of overadditive and underadditive drug effects by means of theoretical, additive dose-response curves. J Pharm Methods. 1980;4:179–188. doi: 10.1016/0160-5402(80)90036-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskind MA, Peskind ER, Kanter KD, Petrie EC, Radant A, Thompson CE, Dobie DJ, Rein RJ, Straits-Tröster K, Thomas RG, McFall MM. Reduction of nightmares and other PTSD symptoms in combat veterans by prazosin: a placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:371–373. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.2.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskind MA. Sustained recovery from chronic alcohol dependence with prazosin treatment of PTSD. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33(Suppl):311A. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen DD, Alexander LL, Raskind MA, Froehlich JC. The α1-adrenergic receptor antagonist, prazosin, reduces alcohol drinking in alcohol-preferring (P) rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009a;33:264–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00829.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen DD, Federoff D, Froehlich JC. Prazosin reduces alcohol drinking in an animal model of alcohol relapse. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009b;33:146A. doi: 10.1111/acer.12789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepard TA, Reuning RH, Aarons LJ. Estimation of area under the curve for drugs subject to enterohepatic cycling. J Pharmacokinetics and Biopharmaceutics. 1985;13:589–608. doi: 10.1007/BF01058903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson TL, Saxon AJ, Meredith CW, Malte CA, McBride B, Ferguson LC, Gross CA, Hart KL, Raskind M. A pilot trial of the alpha-1 adrenergic antagonist, prazosin, for alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:255–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanagel R, Montkowski A, Allingham K, Stöhr T, Shoaib M, Holsboer F, Landgraf R. Anxiety: A potential predictor of vulnerability to the initiation of ethanol self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology. 1995;122:369–373. doi: 10.1007/BF02246268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker SD, Stricker EM, Sved AF. Acute hypertension inhibits thirst stimulated by ANG II, hyperosmolality, or hypovolemia in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;280:R214–R224. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.280.1.R214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallarida RJ. Drug synergism: Its detection and applications. J Pharm Exp Ther. 2001;298:865–872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallarida RJ, Stone DJ, Raffa RB. Efficient designs for studying synergistic drug combinations. Life Sci. 1997;61:417–425. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)01030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trendelenburg U. The action of acetylcholine on the nictitating membrane of the spinal cat. J Pharm Exp Ther. 1962;135:39–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpicelli JR, Watson NT, King AC, Sherman CE, O’Brien CP. Effect of naltrexone on alcohol “high” in alcoholics. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:613–615. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.4.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker BM, Rasmussen DD, Raskind MA, Koob GF. The effects of α1-noradrenergic receptor antagonism on dependence-induced increases in responding for ethanol. Alcohol. 2008;42:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]