Abstract

OBJECTIVES

The capacity of older adults to make health care decisions is often impaired in dementia and has been linked to performance on specific neuropsychological tasks. Within-person across-test neuropsychological performance variability has been shown to predict future dementia. This study examined the relationship of within-person across-test neuropsychological performance variability to a current construct of treatment decision (consent) capacity.

DESIGN

Participants completed a neuropsychological test battery and a standardized capacity assessment. Standard scores were used to compute mean neuropsychological performance and within-person across-test variability.

SETTING

Assessments were performed in the participant’s preferred location (e.g., outpatient clinic office, senior center, or home).

PARTICIPANTS

Participants were recruited from the community with fliers and advertisements, and consisted of men (N=79) and women (N=80) with (N=83) or without (N=76) significant cognitive impairment.

MEASUREMENTS

Participants completed the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool - Treatment (MacCAT-T) and 11 neuropsychological tests commonly used in the cognitive assessment of older individuals.

RESULTS

Neuropsychological performance and within-person variability were independently associated with continuous and dichotomous measures of capacity, and within-person neuropsychological variability was significantly associated with within-person decisional ability variability. Prevalence of incapacity was greater than expected in participants with and without significant cognitive impairment when decisional abilities were considered separately.

CONCLUSIONS

These findings are consistent with an emerging construct of consent capacity in which discrete decisional abilities are differentially associated with cognitive processes, and indicate that the sensitivity and accuracy of consent capacity assessments can be improved by evaluating decisional abilities separately.

Keywords: decisional capacity, executive function, cognitive impairment

OBJECTIVE

Clinical evaluations of health care decision-making capacity are highly consequential for patients and treaters because they consign authority for making potentially life-changing treatment decisions, but outcomes of typical clinical assessment procedures are notoriously inconsistent.1,2 Unreliability in consent capacity assessment has important social and legal implications because erroneous attribution of, and failure to detect, incapacity are both potentially harmful to patients.

A number of standardized assessment instruments aim to improve reliability.3 Each assesses one or more of the four legal standards, or abilities4–7 that define consent capacity: Understanding (comprehension of diagnostic and treatment information), Appreciation (personalization of information through integration with one’s values, beliefs and expectations), Reasoning (evaluation of treatment alternatives in light of potential consequences for everyday life), and Expression of Choice (communication of a treatment decision). This taxonomy corresponds broadly to cognitive models for making treatment decisions.8,9 Legal definitions of incapacity vary by state,10 but a current conceptual model11 posits that each ability is distinct and necessary for decision making; all four abilities must be intact for consent capacity to be preserved. One of the most studied instruments – the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool - Treatment (MacCAT-T)12 – assesses all four abilities.

Others have examined the neuropsychological basis of consent capacity.1,3,13–15 In one recent study of community volunteers,16 neuropsychological scores explained 78% of the common variance in understanding, 39.5% in reasoning, 24.6% in appreciation, and 10.2% in expression of choice. Except for reasoning and appreciation, neuropsychological predictor profiles were distinct for each ability, consistent with a model in which each decisional ability is a discrete element of decision-making capacity. A critical review17 of studies that have examined the relationships between specific neuropsychological abilities and capacity to consent to treatment or research concluded that an association between cognition and decisional capacity is incontrovertible, but a clear pattern of differential relationships between specific neuropsychological and decisional abilities has not yet emerged.

Impaired consent capacity is often a consequence of dementia. Recently Holtzer and colleagues18 reported that within-person across-neuropsychological test variability (i.e., the degree to which each person's performance differed across tasks) predicted incident (future) dementia, independent of overall neuropsychological test performance. Thus, within-person across-neuropsychological test variability is clinically meaningful, more sensitive than conventional clinical assessment for detecting impaired cognition, and indexes a progressive decline in cognition that often leads to loss of consent capacity. In light of previous work demonstrating unique neuropsychological performance contributions to individual decisional abilities, we reasoned that within-person across-neuropsychological test variability should be associated with consent capacity, independent of neuropsychological test performance. To test this hypothesis we administered a broad neuropsychological test battery and the MacCAT-T to a community sample of elderly adults. In addition, based upon the finding that cognitive changes may be detectable years before clinical dementia is diagnosed,18 we hypothesized that focused inquiry would reveal cognitive impairment in a subgroup of this community sample, and that within-person across-neuropsychological test variability would be greater in this subgroup.

METHODS

Participants

The sample consisted of 159 participants (79 men, 80 women). Mean age was 73.8±6.6 years, and mean educational achievement was 14.0±2.9 grade levels. One hundred forty-six (91.8%) of participants self-identified as Caucasian, 11 (6.9%) were African-American, and 2 (1.3%) were neither; all participated in the previously cited study.16

Recruitment

Potential subjects were recruited from the community using fliers and advertisements. Two hundred ninety callers expressed interest in the study. To exclude psychiatric conditions that might diminish cognition, all callers were screened with the Geriatric Depression Scale Short Form (GDS)19 and Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI).20 Sixteen (5.5%) callers were excluded (GDS raw score >10 or BSI T score >70).

Informed Consent Procedure

Our Institutional Review Board approved this study. Written consent was obtained after study information was disclosed in simple direct language, orally and in writing. One participant assented with his guardian’s consent. Participants could discontinue participation at any point, and were compensated for their time.

Group Assignment

As in previous studies,16,21 potential participants (n=274) were screened with the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS)22 modified to include assessment of delayed recall (total possible score = 50).21 Those with TICS scores <40 (N=154) were considered likely to have significant cognitive impairment; all others were tentatively assigned to a healthy comparison group (n=120).

Next, to better characterize the sample, participants with suspected significant cognitive impairment completed the 94-item Dementia Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire (DDSQ),23 with caregiver assistance if needed. Consensus (RG and JM) presumptive clinical diagnoses of DSM-IV dementia were made on the basis of cognitive screening scores, reports of memory and behavioral problems, presence of risk factors for dementia, and medical records; formal clinical diagnostic assessment was not undertaken because the purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between decisional capacity and neuropsychological performance generally. A presumptive clinical diagnosis of dementia was not supported for 34 (22.1%) individuals, 28 (18.2%) callers declined further participation, two could not complete neuropsychological testing, one died, and another was excluded for administrative reasons.

Forty-eight remaining “probable dementia” group participants had TICS scores ≥31, and forty had TICS scores ≤30; this cut-off distinguishes mild from moderate dementia24 and corresponded to 2 standard deviations below the comparison group mean. DDSQ responses suggested likely etiologies for cognitive impairment: vascular dementia, 25 (28.4%); probable Alzheimer dementia, 3 (3.4%); possible Alzheimer dementia, 31 (35.2%); Parkinson disease, 1 (1.1%), traumatic brain injury, 1 (1.1%); and multiple etiologies (including alcohol dementia), 27 (30.7%).

Potential comparison group participants (n = 120) completed the Health Screening Questionnaire25 to exclude health problems that could cause cognitive impairment. Seventeen (14.2%) individuals were excluded on this basis, 13 (10.8%) declined further participation and two were excluded for administrative reasons.

Group assignment occurred prior to neuropsychological and capacity assessment. Groups were similar demographically except for age (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Demographic Data by Group

| Demographic Data | Probable Dementia (N=83) | Comparison (N=76) | Statistic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | t | df | p | |

| Age (years) | 75.3 | 6.3 | 72.1 | 6.5 | −3.094 | 157 | .002 |

| Education (years) | 13.9 | 3.0 | 14.2 | 2.7 | .547 | 156 | .585 |

| χ2 | df | p | |||||

| Sex (M/F) | 41/42 | 38/38 | .006 | 1 | .940 | ||

| Racea | 79/3/1 | 67/8/1 | 2.957 | 2 | .197 | ||

Caucasian/African-American/Other

Assessments

Capacity Assessment

The MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool – Treatment (MacCAT-T)26 utilizes a semi-structured interview to assess capacity to make an actual treatment decision, and it assesses understanding, reasoning, appreciation, and expression of choice separately. For research purposes, we used a standardized vignette21 involving a hypothetical choice between surgical procedures for a non-healing toe ulcer, and scored responses as follows: 2= full response, 1= partial response, 0= no/poor response. Non-weighted item scores were summed to create ability subscores. One original item seemed redundant and was not used, so the maximum score for understanding was 24.

Neuropsychological Testing

Participants completed 11 neuropsychological tests27–33 (Table 2). Summary scores were calculated for digits forward and backwards combined; the three COWA lists; and VSAT subscores. Test sessions were conducted at the participant’s preferred location and lasted approximately 120 minutes with at least one break; additional breaks were offered throughout to minimize fatigue.

TABLE 2.

Neuropsychological Test Performance and Capacity by Group

| Neuropsychological Test | Probable Dementia (N=83) | Comparison (N=76) | Statistic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | t | df | p | |

| Digit Span | 17.24 | 4.13 | 18.58 | 4.24 | 2.014 | 157 | .046 |

| FAS | 35.82 | 12.54 | 40.09 | 12.18 | 2.176 | 157 | .031 |

| Logical Memory I | 34.08 | 12.08 | 41.36 | 8.86 | 4.352 | 150.1 | <.001 |

| Logical Memory II | 18.28 | 9.95 | 25.51 | 7.15 | 5.297 | 148.9 | <.001 |

| Trails A | 48.40 | 26.61 | 39.91 | 13.53 | −2.567 | 124.0 | .011 |

| Trails B | 145.69 | 77.94 | 91.03 | 34.76 | −5.791 | 115.5 | <.001 |

| Vocabulary | 41.13 | 13.04 | 47.36 | 9.47 | 3.464 | 149.5 | .001 |

| Boston Naming Test | 49.47 | 10.96 | 55.51 | 3.64 | 4.744 | 101.3 | <.001 |

| Mazes Test | 19.55 | 4.43 | 22.17 | 3.52 | 4.145 | 154.0 | <.001 |

| VSAT | 157.40 | 52.63 | 184.86 | 36.28 | 3.856 | 146.1 | <.001 |

| Mean Performancea | −.156 | .465 | .171 | .307 | 5.277 | 143.2 | <.001 |

| Variability | .943 | .524 | .757 | .211 | −2.979 | 109.9 | .004 |

| MacCAT-T Scores | |||||||

| Continuous | Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | t | df | p |

| Understanding | 16.92 | 4.21 | 18.80 | 3.09 | 3.242 | 150.0 | .001 |

| Reasoning | 6.65 | 1.33 | 7.29 | .95 | 3.509 | 148.5 | .001 |

| Appreciation | 3.78 | .54 | 3.78 | .58 | −.077 | 157 | .939 |

| Expression of Choice | 1.96 | .19 | 1.97 | .23 | .297 | 157 | .767 |

| Global | 29.31 | 5.26 | 31.84 | 3.48 | 3.600 | 143.3 | <.001 |

| Dichotomous | Intact | % | Intact | % | χ2 | df | pb |

| Understanding | 78 | 94.0 | 76 | 100.0 | 4.727 | 1 | .060 |

| Reasoning | 76 | 91.6 | 75 | 98.7 | 4.207 | 1 | .066 |

| Appreciation | 80 | 96.4 | 72 | 94.7 | .256 | 1 | .710 |

| Expression of Choice | 83 | 100.0 | 75 | 98.7 | .855 | 1 | .622 |

| Global | 71 | 85.5 | 71 | 93.4 | 2.579 | 1 | .128 |

Mean of z scores.

Probabilities for categorical variables computed by Fisher exact method.

Statistical Analyses

Capacity or neuropsychological data were incomplete for 12 comparison (13.6%) and 5 probable dementia group participants (5.7%); they were excluded from analysis. Four variables were analyzed: within-person across-test variability, mean neuropsychological performance, continuous global capacity scores, and dichotomous global capacity ratings. Significance levels are two-tailed (SPSS 17.0).

Computation of Neuropsychological Variables

Within-person across-test neuropsychological variability was computed according to the method of Holtzer et al.18 Each test score was converted to a z score based upon the entire distribution (all participants), and a mean and standard deviation were computed for each participant’s z-transformed test scores. Mean performance was represented by the participant’s mean z score.

Capacity measures

Ability subscores were summed to create a global capacity score for each participant. In addition, global capacity was rated dichotomously as “present” if all four decisional abilities were intact, and “absent” otherwise. For this study, an ability was rated impaired if its score was less than 3 standard deviations below its comparison group mean. In a normal distribution .13% of observations fall below the third standard deviation; if decisional abilities are statistically independent, approximately .8 individuals out of 159 would be expected to have one subscore in that range. This was considered an appropriate level of sensitivity for a community-dwelling sample in which consent capacity generally had not been challenged previously (one participant had a guardian.) We included this supplementary analysis because of its relevance to clinical and legal practice, where capacity determinations are dichotomous.

Group Comparisons

Except for digit span and FAS, neuropsychological test variances were unequal (Levene’s test), so t statistics were computed with pooled variances in those cases. Relationships among clinical and neuropsychological variables were initially evaluated using 2 (group: probable dementia, comparison) x 2 (capacity: absent, present) ANOVAs with within-person variability and mean neuropsychological performance serving as dependent variables.

Hypotheses testing

A stepwise linear regression equation was created in which mean performance, variability and age served as the independent variables, and global capacity score was the dependent variable. A forced hierarchical logistic regression procedure was used to evaluate the effect of mean performance, variability and group on dichotomous global capacity ratings.

RESULTS

Group Comparisons

The comparison group showed higher overall neuropsychological performance, lower within-person variability, and consistently superior task performance compared to the probable dementia group (Table 2). Group differences in digit span performance were accounted for entirely by digits backward. Two-way ANOVA revealed main effects for group and capacity, and a significant group-by-capacity interaction, for mean performance and variability (Table 3). The probable dementia group had significantly lower global capacity scores than the comparison group (mean±S.D. 29.3±5.3 vs. 31.8±3.5, t= 3.60, df= 143.3, p< .001), and this difference was due to lower subscores for understanding (16.9±4.2 vs. 18.8±3.1, t= 3.24, df= 153.3, p= .001) and reasoning (6.65±1.3 vs. 7.29±.95, t= 3.51, df= 148.5, p= .001).

TABLE 3.

Relationship of Group and Capacity to Variability and Mean Performance (z scores)

| Within-Person Neuropsychological Test Variability (2-way ANOVA) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groupa | Capacity | Mean | N | Effects | Sum of Squares | df | F | p |

| C | Absent | .753 | 5 | Group | .920 | 1,155 | 6.432 | .012 |

| Present | .757 | 71 | Capacity | 2.532 | 1,155 | 17.693 | <.001 | |

| PD | Absent | 1.457 | 12 | Group*Capacity | 1.174 | 1,155 | 8.202 | .005 |

| Present | .856 | 71 | ||||||

| Mean Neuropsychological Test Performance (2-way ANOVA) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Capacity | Mean | N | Effects | Sum of Squares | df | F | p |

| C | Absent | .231 | 5 | Group | 3.529 | 1,155 | 24.865 | <.001 |

| Present | .167 | 71 | Capacity | 1.728 | 1,155 | 12.177 | .001 | |

| PD | Absent | −.605 | 12 | Group*Capacity | 1.112 | 1,155 | 7.837 | .006 |

| Present | −.081 | 71 | ||||||

C= comparison group; PD= probable dementia group

Continuous Capacity Ratings

Global capacity scores in the entire sample were significantly correlated with mean neuropsychological performance (r= .712, df=157, p< .001) and within-person variability (r= −.457, df=157, p< .001). Neuropsychological performance and within-person variability were also correlated with one another (r= −.317, df=157, p< .001). Stepwise linear regression revealed that performance and within-person variability independently accounted for statistically significant amounts of variance in global capacity scores (50.7% and 6.0%, respectively, Table 4). Age was significantly correlated with global capacity score (r= −.257, df=157, p= .001), mean performance (r= −.234, df=157, p= .003) and variability (r= .156, df=157, p= .050), but it did not contribute to global capacity scores in the final regression model (beta= −.074, p= .172; Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Stepwise Linear Regression of Global Capacity on Neuropsychological Variables

| Model | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | p | R | R2 | ΔR2 | Variable | Beta | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Regression | 1743.22 | 1 | 1743.22 | 161.71 | <.001 | .712 | .507 | .507 | Performance | .712 | <.001 |

| Residual | 1692.45 | 157 | 10.78 | |||||||||

| 2 | Regression | 1948.11 | 2 | 974.06 | 102.15 | <.001 | .753 | .567 | .060 | Performance | .631 | <.001 |

| Residual | 1487.56 | 156 | 9.54 | Variability | −.257 | <.001 |

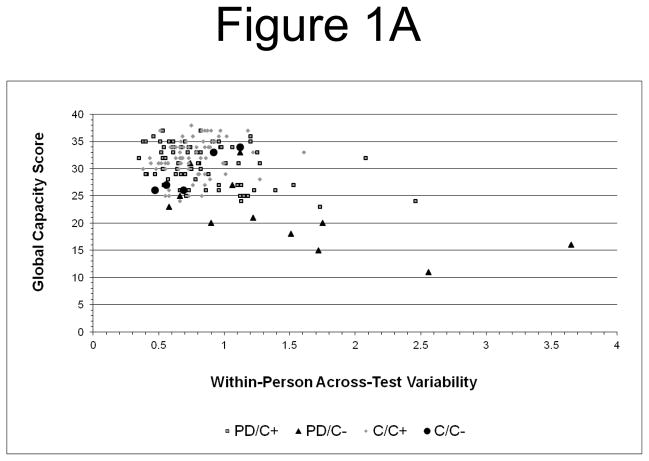

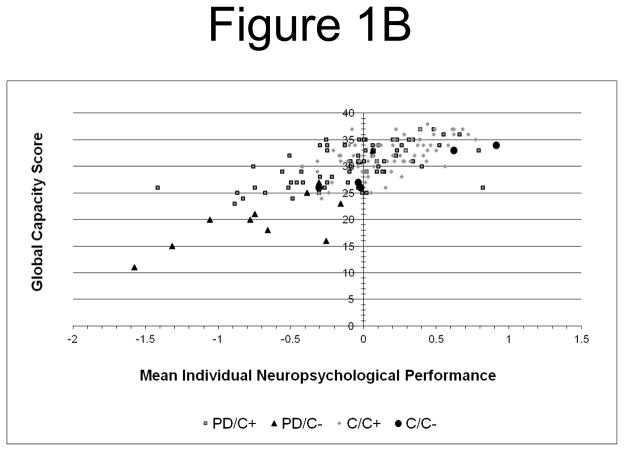

Visual inspection of scatter plots (Figure 1) suggested that a few variability outliers might have disproportionately influenced the results. Quantitative analysis confirmed the presence of 4 severe34 variability outliers in the probable dementia group, but none for global capacity or mean performance. To examine whether severe outliers accounted for the results, analyses were repeated with asymmetrically Winsorized34 variability data (i.e., the 4 severe outlier values were replaced with the next highest value (1.753) in the distribution). The results were essentially unchanged: Variability was correlated with global capacity (r =−.399, df=157, p< .001), and step-wise linear regression was significant (F[2,156]= 93.55, p< .001) with independent contributions from mean performance (beta= .651, R2= .507, p< .001) and variability (beta= −.204, ΔR2= .038, p< .001).

Figure 1.

Figure 1A. Within-Person Across-Test Neuropsychological Variability and Treatment Decision Capacity: Greater within-person variability (z score) is associated with lower global decision capacity scores. (PD/C+ = probable dementia group, capacity present; PD/C− = probable dementia group, capacity absent; C/C+ = comparison group, capacity present; C/C− = comparison group, capacity absent).

Figure 1B. Mean Overall Neuropsychological Performance and Treatment Decision Capacity: Better overall performance (z score) is associated with higher global capacity scores in both groups.

As a further test of the sensitivity of these findings to more extreme neuropsychological performance, we repeated the primary regression analysis with participants whose mean performance was within 1 standard deviation of the entire sample mean (N= 114). The results were again unchanged (F[2,111]= 26.75, p< .001; performance beta= .459, R2= .239, p< .001; variability beta= −.296, ΔR2= .086, p< .001).

Our hypothesis is based upon a model in which capacity requires the contribution of distinct decisional abilities, each dependent upon overlapping but distinct cognitive processes. It follows that within-person variability in cognitive performance should be associated with within-person variability in decisional abilities. To test this prediction, capacity subscale scores were converted to z scores and a standard deviation was computed for each individual’s capacity subscale z scores, exactly as was done for the neuropsychological tasks. As expected, within-person neuropsychological performance variability was correlated with within-person decisional ability variability (r= .227, df=157, p= .004). Decisional ability variability was also strongly inversely correlated with mean individual decisional ability (r= −.763, df=157, p< .001).

Dichotomous Capacity Scores

Global capacity was rated absent in 17 participants (10.7%): 5 were in the comparison group (6.6%) and 12 were in the probable dementia group (14.5%), a statistically insignificant difference (Table 2). Forced hierarchical logistical regression, in which group was entered first followed by mean performance and then variability, confirmed that presence or absence of capacity was not associated with group in the first model (Wald statistic= 2.46, df=1, estimated odds ratio= 2.40, p= .117) or subsequent models (Wald statistic ≤ .06, estimated odds ratios ≤ 1.17, df=1, p≥ .809), but there was a strong trend for an association with performance (Wald statistic= 3.74, estimated odds ratio= 3.82, p= .053) and a significant association with variability (Wald statistic= 4.06, estimated odds ratio= .32, p= .044).

CONCLUSIONS

The main finding of this study is that within-person across-test neuropsychological test performance variability is associated with reduced consent capacity in community-dwelling adults, independent of overall neuropsychological performance. In addition, within-person neuropsychological test performance variability was correlated with within-person decisional ability variability. These findings suggest that in addition to a relationship between overall neuropsychological performance and decisional capacity, such that better performance is associated with greater decisional capacity, intact decisional capacity also rests upon still undefined interactions between a variety of cognitive functional domains.

It is interesting that groups differed only in understanding and reasoning because these abilities are more strongly predicted by neuropsychological performance than are appreciation and expression of choice.16 Other studies35,36 have also reported an especially strong relationship between understanding and neuropsychological test performance, indicating that understanding may be the most cognitively mediated consent task. Appreciation may involve personal values and emotional forms of information processing not captured by the tests used in the present study, but it is also psychometrically weaker than understanding and reasoning subscales because it is based on only 2 items. Expression of choice is similarly limited, and restricted range may have further obscured its relationship with other measures.

The prevalence of dichotomously rated incapacity in both groups was higher than expected using a conservative, statistically defined threshold criterion. Five comparison group participants were rated as lacking capacity, a frequency more than 12 times greater than expected. In contrast, no comparison group global capacity score was more than 3 standard deviations below the group mean. Four of these participants had impaired appreciation, and the fifth participant had impaired expression of choice; one of those with impaired appreciation also had impaired reasoning, but understanding was intact in all. Just as an overall neuropsychological performance score may obscure focal deficits that impact specific abilities, capacity assessments that do not consider each ability separately may fail to detect decisional deficits.

As predicted, within-person neuropsychological test performance variability was significantly higher in the group with significant cognitive impairment. It is intriguing that the mean age difference between groups – 3.2 years – corresponds closely to the mean time to incident dementia in the community-based cohort of Holtzer et al.18 In a very large study37 of community dwelling elder adults with a mean age comparable to that of the present sample, the prevalence of cognitive impairment was 23.4%; age-specific rates showed increasing prevalence with increasing age, and approximately one-fourth of affected individuals were found to meet diagnostic criteria for dementia at 18-month follow-up. More recently, Burton et al38 reported that more than half of hospice patients with no known or obvious cognitive dysfunction demonstrated significant cognitive impairments on neuropsychological testing, and these impairments were associated with impaired treatment decision making capacity. The present findings are consistent with these results.

The probable dementia group performed significantly worse than the comparison group on all neuropsychological tasks, but Digit Span and Logical Memory I scores were higher than expected based on age-adjusted community-dwelling population norms.27 This may reflect the sample’s higher educational attainment compared to population norms;27 our selection process, which used a screening instrument that emphasized memory function and may have unintentionally enriched the sample for individuals with non-memory presentations of mild cognitive impairment;39 or the heterogeneity of likely etiologies for impaired cognition in this group (a substantial portion of participants were suspected of having disorders more likely to affect executive function than memory, e.g., vascular dementia). In this light it may be important that group differences in digit span performance were limited to backwards repetition. Forward and backward digit repetition draw upon anatomically and functionally distinct resources;40 forward span is a simpler, more verbally oriented task whereas backward span engages more complex processes involving transformations and visuospatial imaging processes,41 and their attentional components are also distinct.41 It is also important to point out that our diagnostic assessment was limited because it was intended for purely descriptive purposes, so outcomes may have differed in some cases from what would have been obtained by more thorough clinical assessment. In addition, the participant selection process and local demographic factors may have affected the distribution of dementia subtypes in our sample. Thus, the neuropsychological performance observed in the present sample may not reflect that of participants randomly selected from the community.

In addition to its potential usefulness as a unique index of decisional capacity, within-person neuropsychological performance variability may also influence clinicians’ perceptions of their patients’ ability to make decisions in various contexts. A recent study42 found that performance on subscales of a well known dementia rating instrument differentially predicted how experienced psychiatrists rated individuals on their ability to make decisions about participating in research or appointing a health care proxy, and there was also an interaction between differential subscale performance and relative strictness or leniency in clinician rating styles.

This study has several limitations. First, group assignment was based upon self-reported symptoms and review of available medical records. However, group assignment reflected the consensus of two experienced geriatric mental health clinicians following a careful review of all data, and the fact that groups subsequently differed on capacity and all cognitive measures suggests that the participant classifications were clinically valid. Furthermore, presumptive clinical diagnoses of probable dementia were assigned for the purpose of more fully characterizing the sample; whether participants actually had dementia is not relevant to the study hypotheses.

Second, the MacCAT-T was designed for use in clinical settings to aid conventional assessment, and adapted here for research purposes using a score-only method, so caution must be used when applying these results to clinical situations. Similarly, the choice of a statistical threshold may be questioned because the true distribution of consent capacity in this (or any) population is not known. The statistical criterion was employed to minimize potential experimenter bias, and a level 3 standard deviations below the comparison group mean was selected based upon the statistical expectation that less than 1 participant in our sample would meet this criterion. This criterion is appropriate because findings of incapacity in clinical situations are conservative, in that individuals are assumed to have capacity unless the examiner can prove its absence according to legal evidentiary standards. Thus, a stringent statistical criterion was felt to be consistent with current practice, but the prevalence of treatment consent incapacity reported in this study should not be taken to estimate its prevalence in the community. These results suggest that subtle changes in consent capacity may be more common than has been appreciated and, like the previously reported18 relationship between within-person neuropsychological test performance variability and dementia, may precede clinically overt impairment. The loss of treatment consent capacity may advance incrementally, mirroring underlying changes in neurocognition, so may be detectable in its earliest stages only by examining each decisional ability separately.

Another potential limitation of this study is that z scores were computed on skewed distributions with occasional severe outliers. Statistical transformations failed to normalize test performance distributions, and there was no objective basis for eliminating the outliers, so z scores were computed on raw data. We believe this was justified for the following reasons: (a) the obtained data likely represent true variance in the population; (b) the prevalence of severe outliers was low (less than half of the neuropsychological measures had any severe outlier, and in these the rate was 3.8% or less), so their contribution was small; (c) the standard deviation, on which z score computations are based, is a simple measure of dispersion that is not dependent upon distribution assumptions; (d) in secondary analyses, elimination of severe outliers by asymmetric Winsorization did not alter the results, nor did restricting the analysis to a subsample of individuals whose mean neuropsychological performance was within 1 standard deviation of the group mean. It is important to acknowledge that intrapersonal factors such as motivation, and psychometric non-equivalence across tests, may have contributed to within-person variability. Finally, the small number of individuals with impaired capacity reduced statistical power and may account for the statistically insignificant group difference.

In summary, within-person across-test neuropsychological test variability appears to contribute to healthcare treatment decision-making capacity, independent of overall neuropsychological performance, and may index within-person variability across decisional abilities. The prevalence of decisional impairment was higher than expected in this community-dwelling non-psychiatric sample of elderly participants with and without probable dementia, which may be accounted for by an assessment procedure that evaluated decisional abilities separately, leading to increased sensitivity in detecting impaired consent capacity.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: This research was supported by a NIMH grant to Jennifer Moye (R29 MH57104), and with resources and the use of facilities at the VA Boston Healthcare System. It was conducted at the Brockton campus of the VA Boston Healthcare System, in Massachusetts. The authors thank Jennifer J. Vasterling, PhD for her helpful comments and suggestions in the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: No disclosures to report.

Authors’ Contributions: All authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design (RG), or acquisition of data (JM,RG,AA), or analysis and interpretation of data (RG,JM,MK,AA); participated in critical revision for intellectual content (RG,JM,MK,AA); and approved the version being submitted for review (RG,JM,MK,AA).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Marson DC, Schmitt FA, Ingram KK, et al. Determining the competency of Alzheimer patients to consent to treatment and research. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Dis. 1994;8(suppl 4):5–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marson DC, McInturff B, Hawkins L, et al. Consistency of physician judgments of capacity to consent in mild Alzheimer's disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:453–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb05170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Veterans Affairs. Clinical assessment for competency determination: A practice guideline for psychologists. Milwaukee: Department of Veterans Affairs National Center for Cost Containment; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tepper A, Elwork A. Competency to consent to treatment as a psychological construct. Law Hum Behav. 1984;8:205–223. doi: 10.1007/BF01044693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drane JF. The many faces of competency. Hastings Center Report. 1985;15:17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Appelbaum PS, Grisso T. Assessing patients' capacities to consent to treatment. New Eng J Med. 1988;319:1635–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198812223192504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roth LH, Meisel CA, Lidz CA. Tests of competency to consent to treatment. Can J Psychiatry. 1997;134:279–284. doi: 10.1176/ajp.134.3.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moye J. Theoretical frameworks for competency assessments in cognitively impaired elderly. J Aging Stud. 1996;10:27–42. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marson DC, Harrell LE. Neurocognitive changes associated with loss of capacity to consent to medical treatment in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. In: Park DC, Morrell REW, Shifren K, editors. Processing of Medical Information in Aging Patients: Cognition and Human Factors Perspectives. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1999. pp. 109–126. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berg JW, Appelbaum PS, Lidz CW, et al. Informed consent: Legal theory and clinical practice. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Welie SPK. Criteria for patient decision making (in)competence: A review of and commentary on some empirical approaches. Med Health Care Philosophy. 2001;4:139–151. doi: 10.1023/a:1011493817051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grisso T, Appelbaum P. MacArthur Competency Assessment Tool for Treatment (MacCAT-T) Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SYH, Karlawish JHT, Caine ED. Current state of research on decision-making competence of cognitively impaired elderly persons. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10:151–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holzer JC, Gansler DA, Moczynski NP, et al. Cognitive functions in the informed consent evaluation process: a pilot study. J Am Acad Psychiatr Law. 1997;25:531–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marson DC, Chatterjee A, Ingram KK, et al. Toward a neurologic model of competency: cognitive predictors of capacity to consent in Alzheimer’s disease using three different legal standards. Neurology. 1996;46:666–672. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.3.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gurrera RJ, Moye J, Karel MJ, et al. Cognitive performance predicts treatment decisional abilities in mild to moderate dementia. Neurology. 2006;66:1367–1372. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000210527.13661.d1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palmer BW, Savla GN. The association of specific neuropsychological deficits with capacity to consent to research or treatment. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2007;13:1047–1059. doi: 10.1017/S1355617707071299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holtzer R, Verghese J, Wang C, et al. Within-person across-neuropsychological test variability and incident dementia. JAMA. 2008;300:823–830. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.7.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric depression scale: Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontol. 1986;5:165–173. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Derogatis LR. Brief symptom inventory: Administration, scoring and procedures manual. Minneapolis: National Computer Systems; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moye J, Karel MJ, Azar AR, et al. Capacity to consent to treatment: empirical comparison of three instruments in older adults with and without dementia. The Gerontologist. 2004;44:166–175. doi: 10.1093/geront/44.2.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brandt J, Welsh KA, Breitner JC, et al. Hereditary influences on cognitive functioning in older men: A study of 4000 twin pairs. Arch Neurol. 1993;50:599–603. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1993.00540060039014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rogers RL, Meyer JS. Computerized history and self-assessment questionnaire for diagnostic screening among patients with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1988;36:13–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1988.tb03428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Welsh KA, Breitner JCS, Magruder-Habib KM. Detection of dementia in the elderly using the telephone interview for cognitive status. Neuropsych Neuropsychol Behav Neurol. 1993;6:103–110. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christensen KC, Moye J, Armson RR, et al. Health screening and random recruitment for cognitive aging research. Psychology and Aging. 1992;7:204–208. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.7.2.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grisso T, Appelbaum PS. MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool - Treatment (MacCAT-T) Manual. Worcester, MA: University of Massachusetts; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wechsler DA. Wechsler memory scale – III: Administration and Scoring Manual. New York: Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wechsler DA. Wechsler adult intelligence scale - III manual. New York: Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adjutant General's Office. Army Individual Test Battery. Washington, DC: War Department; 1944. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trenerry MR, Crosson B, DeBoew J, et al. Visual search and attention test. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaplan EF, Goodglass H, Weintraub S. In: The Boston naming test. Boston E Kaplan, Goodglass H., editors. 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spreen O, Benton AL. Neurosensory center comprehensive examination for aphasia. Victoria, BC: Department of Psychology, University of Victoria; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Christensen KJ, Multhaup KS, Norstrom S, et al. Cognitive battery for dementia: Development and measurement characteristics. Psychol Assess. 1991;3:168–174. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheskin DJ. Handbook of parametric and nonparametric statistical procedures. 4. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marson DC, Cody HA, Ingram KK, et al. Neuropsychological predictors of competency in Alzheimer's disease using a rational reasons legal standard. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:955–959. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540340035011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dymek MP, Atchison P, Harrell L, et al. Competency to consent to medical treatment in cognitively impaired patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 2001;56:17–24. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Unverzagt FW, Gao S, Baiyewu O, et al. Prevalence of cognitive impairment: Data from the Indianapolis Study of Health and Aging. Neurology. 2001;57:1655–1662. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.9.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burton CZ, Twamley EW, Lee LC, et al. Undetected cognitive impairment and decision-making capacity in patients receiving hospice care. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20:306–316. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3182436987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson JK, Vogt BA, Kim R, et al. Isolated executive impairment and associated frontal neuropathology. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;17:360–367. doi: 10.1159/000078183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rapport LJ, Webster JS, Dutra RL. Digit span performance and unilateral neglect. Neuropsychologia. 1994;32:517–525. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(94)90141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reynolds CR. Forward and backward memory span should not be combined for clinical analysis. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 1997;12:29–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palmer BW, Ryan KA, Kim HM, Karlawish JH, Appelbaum PS, Kim SY. Neuropsychological correlates of capacity determinations in Alzheimer disease: Implications for assessment. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012 doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3182423b88. e-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]