Abstract

Background

Research in animal models suggest that transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) and conditioned pain modulation (CPM) produce analgesia via two different supraspinal pathways. No known studies have examined whether TENS and CPM applied simultaneously in human subjects will enhance the analgesic effect of either treatment alone. The purpose of the current study was to investigate whether the simultaneous application of TENS and CPM will enhance the analgesic effect of that produced by either treatment alone.

Methods

Sixty healthy adults were randomly allocated into 2 groups: 1) CPM plus Active TENS; 2) CPM plus Placebo TENS. Pain threshold for heat (HPT) and pressure (PPT) was recorded from subject’s left forearm at baseline, during CPM, during Active or Placebo TENS, and during CPM plus Active or Placebo TENS. CPM was induced by placing the subjects’ contralateral arm in a hot water bath (46.5°C) for two minutes. TENS (100µs, 100Hz) was applied to the forearm for 20 minutes at a strong but comfortable intensity.

Results

Active TENS alone increased PPT (but not HPT) more than Placebo TENS alone (p=0.011). Combining CPM and Active TENS did not significantly increase PPT (p=0.232) or HPT (p=0.423) beyond CPM plus Placebo TENS. There was a significant positive association between PPT during CPM and during Active TENS (r2=0.46, p=0.003).

Conclusions

TENS application increases PPT, however combining CPM and TENS does not increase the CPM’s hypoalgesic response. CPM effect on PPT is associated with effects of TENS on PPT.

Keywords: Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation, Pain Measurement, Pain Threshold

1. Introduction

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) is an established clinical tool for the non-pharmacological control of pain (Aubin and Marks 1995; Desantana et al., 2009b; Emmiler et al., 2008; Lofgren and Norrbrink 2009; Platon et al., 2010). Experimental pain studies using healthy subjects have shown that TENS increases pressure pain threshold (PPT) (Chesterton et al., 2003; Claydon et al., 2008; Liebano et al., 2011; Pantaleao et al., 2011), however the effects of TENS on heat pain threshold (HPT) are still controversial (Palmer et al., 2004; Rakel et al., 2010; Tong et al., 2007). Conditioned pain modulation (CPM; formerly termed diffuse noxious inhibitory control or DNIC) is a phenomenon that involves a tonic noxious stimulus that produces large-scale decrease in pain outside the area of the stimulus and is generally thought to measure the integrity of the endogenous pain inhibitory systems. CPM can be summarized as “pain inhibits pain” and was originally described in 1979 (Le Bars et al., 1979). This pain inhibitory mechanism is presumed to operate through activation of descending supraspinal inhibitory pathways initiated by release of endogenous opioids (Kraus et al., 1981). Animal studies have shown that heterotopic noxious conditioning stimulation causes a powerful and widespread inhibition of wide dynamic range (WDR) and nociceptive specific neurons in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. CPM has also been identified as an advanced psychophysical measure with high clinical relevancy in the characterization of one’s capacity to modulate pain and consequently one’s susceptibility to acquire pain disorders (Pud et al., 2009). Previous studies have also demonstrated that CPM increases PPT (Sowman et al., 2011) and HPT (Tousignant-Laflamme and Marchand 2009).

Both CPM and TENS activate the endogenous pain inhibitory systems and could interact. Research in animal models suggests TENS and CPM both produce analgesia at the level of the spinal cord via two different supraspinal pathways: rostral ventral medulla (RVM) / periaqueductal grey (PAG) in the midbrain and medullary reticularis nucleus dorsalis (MdD) in the medulla, respectively (Bouhassira et al., 1992; de Resende et al., 2011; Desantana et al., 2009a; Kalra et al., 2001; Sluka and Walsh 2003; Villanueva 2009; Villanueva et al., 1996). Both pathways converge at the level of the spinal cord using similar inhibitory neurotransmitters, but may also be activated by similar cortical sites such as the cingulate cortex (Egsgaard et al., 2012; Kocyigit et al., 2012). As CPM is generally used to measure the integrity of endogenous inhibition, and TENS uses endogenous inhibition to produce analgesia, CPM may also be a useful clinical tool to predict the effectiveness of TENS. The aim of the current study was to investigate 1) whether the simultaneous application of TENS and CPM will enhance the analgesic effect of that produced by either treatment alone, and 2) whether the analgesia produced by CPM is associated with the effectiveness of TENS. The hypotheses of this study were that CPM combined with TENS will result in enhanced analgesia, and that CPM analgesia will be associated with TENS analgesia.

2. Methods

2.1 Subjects

Sixty healthy, TENS-naïve, pain-free subjects (30 men, 30 women; mean age 25.84 ± 5.54 years; age range 18–40 years) were recruited from the local and University of Iowa community after approval was obtained from the local Institutional Review Board. The period of recruitment was from September, 2009 to February, 2010. Subjects were screened and excluded if they had altered skin sensation, recent trauma in upper limbs, cardiac pacemaker, pregnancy, or if they were receiving any type of pain medication. Demographic information was collected for all subjects using a demographic form adapted from a previous study (Liebano et al., 2011). Demographic information included gender, age, body mass index (BMI) and race using standardized questions with established content validity.

2.2 Randomization and Sample Size Calculation

After the participants provided written informed consent, they were stratified by gender and randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to 1 of 2 groups: 1) CPM plus active TENS (n=40), 2) CPM plus placebo TENS (n=20). A 2:1 randomization method (active TENS group:placebo TENS group) was used because previous studies have not shown hypoalgesic effect with placebo TENS application in healthy subjects (Liebano et al., 2011; Pantaleao et al., 2011; Rakel et al., 2010) and to improve study’s power. Randomization was performed using the sequentially numbered, opaque sealed envelopes (SNOSE) allocation concealment method (Doig and Simpson 2005; Scales and Adhikari 2005). The envelopes were stored in a secure cabinet that only the allocation investigator had access to and were opened immediately prior to intervention allocation.

The sample size was calculated considering a difference of 100 kPa between groups and a standard deviation of 94 kPa obtained from previous data on PPT and TENS (Liebano et al., 2011). At a significance level of 0.05 and power of 80%, the required sample size in each group was 19 participants (Minitab, v.15, State College, PA). Allowing for attrition, 20 participants were therefore recruited for placebo TENS group and 40 participants for active TENS group, for a total of 60 participants. Four subjects were excluded (n = 2 in each group) because their pain thresholds to heat at baseline were extremely low (35.9 and 36.6 °C) or because they could not tolerate the CPM test.

2.3 Pressure Pain Threshold

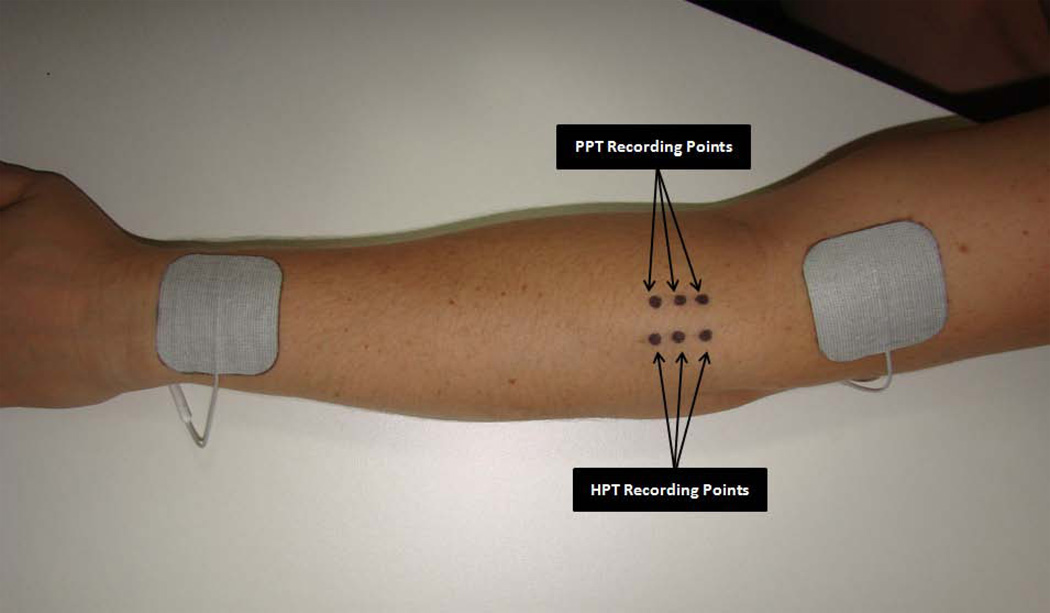

Pressure-pain threshold (PPT) has been measured to reflect pressure pain sensitivity of deep tissues (Kosek et al., 1999). PPT was assessed as the primary outcome measure using a Somedic Type II digital pressure algometer (Somedic Inc, Hörby, Sweden) by an assessor who was blinded to group allocation at three marked spots along the extensor mass of the left forearm (2, 3 and 4cm below the elbow crease) (Fig 1). The pressure was applied perpendicularly to the skin at a rate of 40kPa/s using a flat, 1cm2 circular probe covered with 1mm of rubber to avoid any skin pain from sharp metal edges (Leffler et al., 2002; 2003). Subjects were instructed to press the algometer button when pressure was first perceived as pain and the algometer was retracted at this point (Liebano et al., 2011; Rakel et al., 2010). The average of the PPT scores recorded at the 3 points was used as the final value at each measurement time. Each subject had 2 practice trials on the non-testing forearm followed by the data collection round.

Figure 1.

The placement of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation electrodes and recording sites for pressure pain threshold (PPT) and heat pain threshold.

2.4 Heat Pain Threshold

Heat pain threshold (HPT) was assessed using a TSAII NeuroSensory Analyzer (Medoc Ltd, Ramat Yishai, Israel) with a 16 × 16-mm stimulator. Temperature started at 34°C and increased by 1°C/s to a maximum of 52°C. The thermal stimulus was terminated when the subject first perceived the sensation as changing from heat to pain. If pain was not perceived by 52°C, the test would be stopped for subject safety and this temperature would be recorded as the pain threshold (Rakel et al., 2010). Nevertheless all participants presented HPTs below 52°C. Subjects were familiarized with the assessment by completing 2 practice trials on their non-testing forearm. HPTs were assessed at 3 marked sites located 1cm lateral to the PPTs sites on the subject’s left forearm (over the extensor muscle mass) (Fig 1), and the average of the temperatures recorded at the 3 points was used as the final value at each measurement time.

2.5 Activation of Conditioned Pain Modulation

A hot water bath (Proline RP 1840, Lauda, Germany) was used to induce pain and trigger the CPM response (Moont et al., 2011; 2012; Staud et al., 2003; Streff et al., 2011; Yarnitsky et al., 2008). The water was constantly recirculated to avoid laminar cooling around the subject’s skin (Staud et al., 2003). The conditioning stimulus consisted of the immersion of the subjects’ right hand and forearm in a hot water bath (46.5°C) to just below the elbow for two minutes. This type of conditioning stimulus has been widely used and the heat-induced pain stimuli ranged from 45 to 66.58 on a 0 to 100 scale (0 = no pain and 100 = worst pain imaginable) (Staud et al., 2003; Yarnitsky et al., 2008). PPT and HPT were recorded 30 seconds after immersion from the three spots over the left forearm as described above.

2.6 TENS Procedure

The subject’s skin was cleansed with mild soap and water, and 2 square self-adhesive electrodes (5×5cm) (StimCare Premium Electrodes, Empi Inc., St. Paul, MN) were placed 1cm proximal to the elbow crease and 1cm proximal to the wrist crease on the dorsum of the left upper limb (Fig 1).

Two TENS units were used: an active and a placebo TENS unit. The active unit applied high frequency TENS (continuous mode, 100Hz, 100µs pulse duration) at a strong but comfortable intensity (including motor level stimulation) as dictated by each subject, for 20 minutes to the left forearm. The placebo TENS was applied using a placebo unit that was identical in appearance to the active unit. This unit actively applied TENS (continuous mode, 100Hz, 100µs) at sensory threshold intensity for 30 seconds and then the current ramped off over the next 15 seconds. All devices were Rehabilicare Maxima (Empi Inc., St. Paul, MN) TENS units delivering a rectangular, balanced, asymmetrical biphasic pulsed current.

TENS applications were performed by an investigator who did not participate in outcome assessments to ensure appropriate TENS blinding. During the pain measurements, the intensity of TENS was decreased and kept at a sensory intensity level to ensure the pain assessor was kept blind to the subject’s group allocation.

2.7 General Overview of Protocol

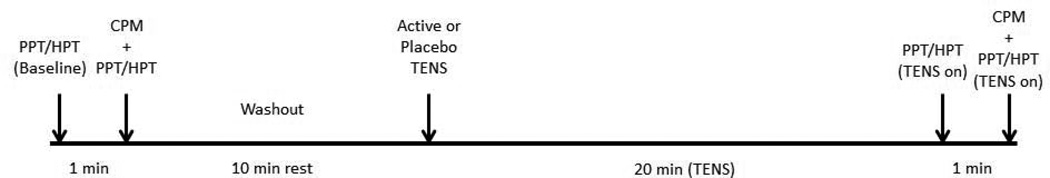

After obtaining consent and demographic information, the subjects were randomized and asked to remain seated in a comfortable upright position during all procedures. The left forearm was cleansed, the PPT and HPT areas were marked as described above, and the TENS electrodes were applied. Each subject underwent one familiarization test on the non-testing forearm prior to baseline PPT and HPT measurements. PPTs and HPTs were each measured three times in an alternating fashion at baseline. One minute after baseline PPT and HPT measurements, the subject was asked to immerse his/her right hand and forearm in the hot water bath (46.5°C) for two minutes (CPM). Thirty seconds after immersion PPTs and HPTs were recorded again from the three spots over the left forearm in an alternating fashion as described above. When these tests were finished, subjects removed their right upper limb from the water and were informed they should rest for 10 minutes (washout period). The pain assessor left the room and another investigator applied the correct TENS unit (active or placebo) for 20 minutes. After 20 minutes, the pain assessor returned and remeasured PPTs and HPTs. One minute after pain measurements, subjects were asked to immerse their right upper limb again (TENS was still on) and one more round of pain assessments was performed. Investigators used pre-written scripts to explain the procedures to subjects in order to guarantee that given information was consistent. During rest times and during TENS application, subjects remained seated and alone to obviate distraction and consequently the impact of distraction on pain levels. Figure 2 shows the timeline of the experimental protocol.

Figure 2.

Experimental protocol timeline.

2.8 Blinding Assessment

At the conclusion of testing, the TENS investigator asked the subject “Do you think you received active TENS, placebo TENS or don’t know?” The pain assessor was asked “Do you think the subject received active TENS, placebo TENS or don’t know?” Their responses were recorded and used to gauge the adequacy of subject and investigator blinding (Rakel et al., 2010).

2.9 Statistical Analyses

PPTs and HPTs were calculated as the mean of the 3 sites tested at each time point, and data were standardized to show a variation from baseline (difference scores), where positive values represent hypoalgesia and negative values represent hyperalgesia. Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables and tests for normal distribution (Shapiro Wilk) were carried out. The PPT and HPT data were normally distributed and were therefore analyzed using a repeated measures ANOVA. Post hoc testing was performed with a Tukey’s test to measure any differences between groups. Associations among the difference scores of PPT and HPT during TENS and CPM were assessed using Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficients. Chi-square test was used to compare blinding of the groups against an expected result of 50:50 blinding (ie, chance). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All analyses were performed using SPSS (version 17.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M.

3. Results

Demographic information for each group is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study participants

| CPM then Placebo TENS (n = 20) |

CPM then Active TENS (n = 40) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 10 | 20 |

| Female | 10 | 20 |

| Age (Mean ± SD) | 25.90 ± 4.51 | 25.74 ± 3.75 |

| BMI (Mean ± SD) | 25.16 ± 3.87 | 26.87 ± 3.11 |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 15 (75%) | 30 (75%) |

| African American | 2 (10%) | 3 (7.5%) |

| Asian | 2 (10%) | 5 (12.5%) |

| Other | 1 (5%) | 2 (5%) |

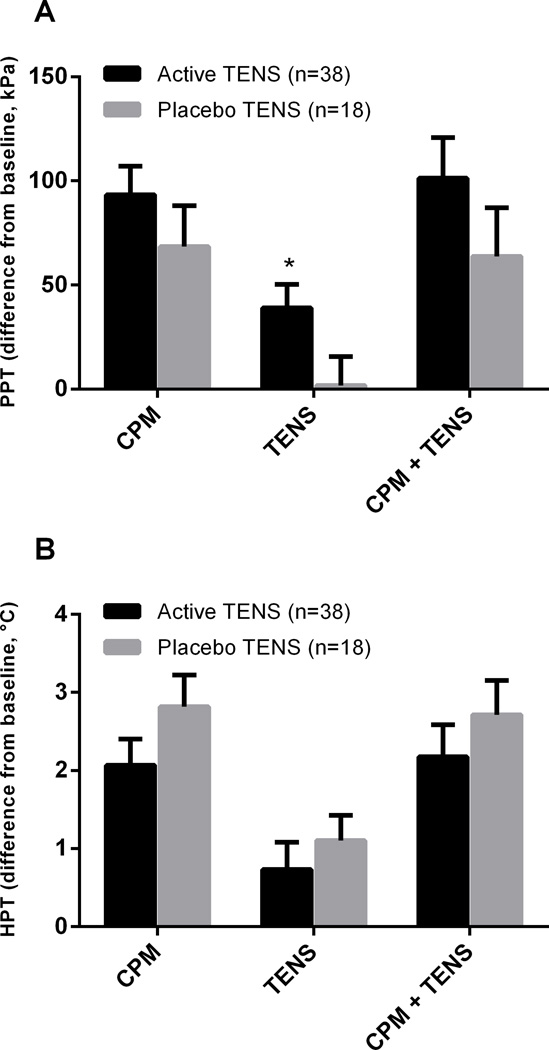

The difference scores of PPT and HPT during CPM alone, during active TENS and placebo TENS alone, during CPM plus active TENS and during CPM plus placebo TENS are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Mean PPT (A) and HPT (B) difference scores (±SEM) for placebo TENS plus CPM and active TENS plus CPM groups during CPM alone, during TENS alone, and during CPM in combination with TENS. *Significantly different from placebo TENS (p=0.011).

Both groups increased PPT and HPT during CPM alone, without significant differences between groups (p =0.235 and p=0.186 respectively). Active TENS increased PPT (p=0.011), but not HPT (p=0.504) when compared to placebo TENS during TENS application alone. No significant differences between groups were observed when combined CPM plus active TENS or CPM plus placebo TENS on PPT (p=0.232) and HPT (p=0.423).

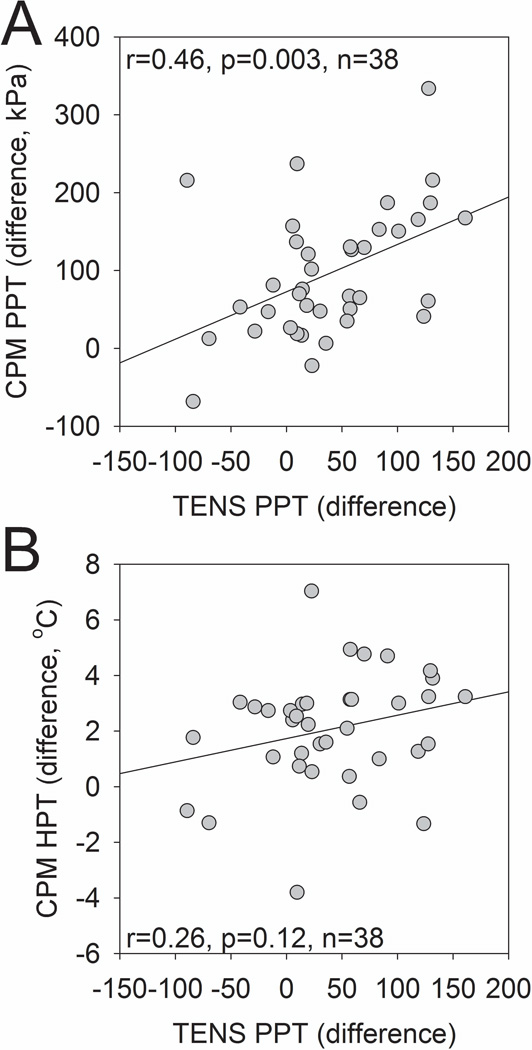

There was a significant positive correlation between the difference scores in PPT during CPM and during active TENS (r2=0.46, p=0.003) (Figure 4A). The correlation observed between HPT difference scores during CPM and PPT during active TENS was not significant (r2=0.26, p=0.12) (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Scatter plot and correlation between difference scores of PPT during active TENS and CPM (A). Scatter plot and correlation between difference scores of HPT during CPM and PPT during active TENS (B).

3.1 Assessment of Blinding

The outcome assessor correctly identified that subjects received active TENS treatment in 5% of the cases (2 of 38). He/she responded “don’t know” when asked about group allocation for 100% of subjects (18 of 18) in the placebo TENS group. In other words, the outcome assessor was blinded 96.4% of the time, indicating successful TENS blinding (p<0.0001).

Subjects were blinded to the treatment 83.3% (15 of 18) of the time in the placebo TENS group and 73.7% (28 of 38) in the active TENS group. The rate of blinding in both experimental groups was different than chance (random 50:50 probability), showing adequate subject TENS blinding (p=0.0047 and p=0.0035 respectively).

4. Discussion

Although the mechanisms of action of TENS and CPM have been extensively investigated in previous animal studies (Bouhassira et al., 1992; de Resende et al., 2011; Desantana et al., 2009a; Kalra et al., 2001; Villanueva et al., 1996) to our knowledge this is the first study assessing the interaction of both modalities in humans. Pathways responsible by CPM and TENS analgesia originate from different areas of the central nervous system, but both are activated by opioid and alpha-adrenergic receptors activation (de Resende et al., 2011; Desantana et al., 2009a; DeSantana et al., 2008; King et al., 2005; Leonard et al., 2011; Leonard et al., 2010; Wen et al., 2010). Thus the hypothesis of the present study was that CPM and TENS could interact to enhance the hypoalgesic response. The results show that TENS and CPM each produce a hypoalgesic response when applied in isolation, but there is no additional increase in the hypoalgesia when combining both modalities, because no differences were observed between active TENS plus CPM and placebo TENS plus CPM. The proposed explanation for this finding is that, when activating CPM, the descending pathways from MdD would produce a large inhibitory effect on T cells in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Thus, when TENS activates the descending pathways from PAG/RVM a maximal hypoalgesic effect was already obtained by CPM activation producing no additional hypoalgesia. This hypothesis remains to be confirmed in future experimental studies.

The data from the current study indicate that PPT changes during CPM were positively correlated with PPT changes during TENS application, suggesting that CPM may be a useful method to determine potential effectiveness of TENS clinically. HPT changes with CPM, however, did not correlate with PPT changes during TENS suggesting that CPM predicts effects of TENS in a modality-specific manner. This is supported by previous work showing that there are different subsets of nociceptors responsible for evoking heat or mechanical pain (Cavanaugh et al., 2009; Yarnitsky and Ochoa 1990). Heat pain is produced by activity of the TRPV1+ population of nociceptors (C-fibers) and can be blocked by mu-opioid receptor agonists (Cavanaugh et al., 2009; Scherrer et al., 2009). By contrast, mechanical pain is generated by activity in different populations (myelinated and unmyelinated nonpeptidergic nociceptors) and can be selectively blocked by delta-opioid receptor agonists (Cavanaugh et al., 2009; Lawson et al., 2008; Scherrer et al., 2009). Experimental studies in rats suggested that low-frequency TENS (4–10Hz) predominantly activates peripheral and central mu-opioid receptors whereas high-frequency TENS (100–130Hz) does not (Kalra et al., 2001; Sabino et al., 2008; Sluka et al., 1999). This can explain why high-frequency TENS increased PPT but did not increase HPT. These data are in agreement with other studies that observed an increase in PPT in healthy adults (Cowan et al., 2009; Liebano et al., 2011; Pantaleao et al., 2011; Rakel et al., 2010) but no significant changes in HPT with high-frequency TENS (100Hz) application (Palmer et al., 2004; Rakel et al., 2010). Some authors observed an increase in HPT when applying TENS with an alternating frequency of 2Hz and 100Hz (Tong et al., 2007). It is possible that this alternation between low and high-frequency TENS released opioids and activated peripheral mu-opioid receptors in the TRPV1+ nociceptors. A few studies have shown an increase of HPT with high-frequency TENS application (Buonocore and Camuzzini 2007; Cheing and Hui-Chan 2003; Pertovaara 1980). Nevertheless, they failed to include a control or placebo TENS group. Moreover, the rate of assessor or subject blinding was not described. These differences in experimental protocols may have been responsible for discrepancies in results.

The rate of pain assessor blinding (96.4%) in the current study is in accordance with previous similar TENS studies ranging from 96% to 100% (Cowan et al., 2009; Liebano et al., 2011; Moran et al., 2011). Subject blinding in the active TENS group in the current study (73.7%) was higher than observed in other studies (20 to 50%) (Cowan et al., 2009; Liebano et al., 2011; Moran et al., 2011; Pantaleao et al., 2011). Blinding subjects when studying physical modalities such as cold, heat, electrical stimulation, acupuncture and manual therapy is an important and challenging issue (Kawchuk et al., 2009; Takakura et al., 2011). The rate of blinding in subjects who received the placebo TENS (83.3%) was also higher than observed in previous studies (40 to 48%) (Liebano et al., 2011; Rakel et al., 2010). This may be explained by the fact that early studies using this placebo unit applied TENS for a short period of time (30 or 42 seconds) at maximally tolerable intensity (Liebano et al., 2011; Pantaleao et al., 2011; Rakel et al., 2010). Applying a maximally tolerable intensity for only a short period of time makes it easier for subjects to notice when the current ramps off (Liebano et al., 2011). In the current study the transient placebo TENS was delivered at a sensory threshold intensity level in an effort to improve blinding (Cowan et al., 2009; Moran et al., 2011). A similar rate of blinding was also observed by other authors (85%) using this same protocol (Moran et al., 2011).

The present study has certain limitations that need to be taken into account. Some of the limitations include the generalizability of the results. Subjects were pain-free, thus future clinical studies should be performed to confirm these results in patients experiencing pain. Second, the researcher responsible for applying TENS was not blinded to group allocation; however efforts were made to reduce bias by blinding pain assessor during tests by having the researcher use a pre-written script that described TENS effectiveness and expectations in a similar manner. Lastly, it is possible that CPM produced a ceiling-like effect obviating a further increase in PPT or HPT with TENS application. However, there was a large variability in CPM response as well as TENS response with a proportion showing minimal changes and other showing robust changes.

In summary, this study showed that both CPM and TENS cause hypoalesgia when administered independently but combining CPM and TENS does not increase the hypoalgesic response. Moreover, CPM effect on PPT is associated with effect of TENS on PPT.

What's already known about this topic?

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) and conditioned pain modulation (CPM) produce analgesia via two different supraspinal pathways. No known studies have examined whether TENS and CPM applied simultaneously in human subjects will enhance the analgesic effect of either treatment alone.

What does this study add?

This study shows that combining CPM and TENS does not increase the hypoalgesic response.

CPM effect on pressure pain threshold is associated with effects of TENS on PPT, suggesting that CPM may predict TENS analgesia.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: Supported in part by the University of Iowa Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) Pilot Grant and the National Institutes of Health R03 5R03NR010405-02.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

REL provided data collection and wrote the manuscript.

CGTV and NAC provided data collection.

BR, SM and DMW provided concept/idea/research design.

JEL provided subject’s selection and data collection.

KAS provided concept/idea/research design and data analysis.

All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript and approved the final version of the study to be published.

References

- Aubin M, Marks R. The efficacy of short-term treatment with transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for osteo-arthritic knee pain. Physiotherapy. 1995;81:669–675. [Google Scholar]

- Bouhassira D, Villanueva L, Bing Z, le Bars D. Involvement of the subnucleus reticularis dorsalis in diffuse noxious inhibitory controls in the rat. Brain Res. 1992;595:353–357. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91071-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonocore M, Camuzzini N. Increase of the heat pain threshold during and after high-frequency transcutaneous peripheral nerve stimulation in a group of normal subjects. Eura Medicophys. 2007;43:155–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh DJ, Lee H, Lo L, Shields SD, Zylka MJ, Basbaum AI, Anderson DJ. Distinct subsets of unmyelinated primary sensory fibers mediate behavioral responses to noxious thermal and mechanical stimuli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:9075–9080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901507106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheing GL, Hui-Chan CW. Analgesic effects of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation and interferential currents on heat pain in healthy subjects. J Rehabil Med. 2003;35:15–19. doi: 10.1080/16501970306101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesterton LS, Foster NE, Wright CC, Baxter GD, Barlas P. Effects of TENS frequency, intensity and stimulation site parameter manipulation on pressure pain thresholds in healthy human subjects. Pain. 2003;106:73–80. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00292-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claydon LS, Chesterton LS, Barlas P, Sim J. Effects of simultaneous dual-site TENS stimulation on experimental pain. Eur J Pain. 2008;12:696–704. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan S, McKenna J, McCrum-Gardner E, Johnson MI, Sluka KA, Walsh DM. An investigation of the hypoalgesic effects of TENS delivered by a glove electrode. J Pain. 2009;10:694–701. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Resende MA, Silva LF, Sato K, Arendt-Nielsen L, Sluka KA. Blockade of Opioid Receptors in the Medullary Reticularis Nucleus Dorsalis, but not the Rostral Ventromedial Medulla, Prevents Analgesia Produced by Diffuse Noxious Inhibitory Control in Rats With Muscle Inflammation. J Pain. 2011;12:687–697. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desantana JM, da Silva LF, de Resende MA, Sluka KA. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation at both high and low frequencies activates ventrolateral periaqueductal grey to decrease mechanical hyperalgesia in arthritic rats. Neuroscience. 2009a;163:1233–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.06.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desantana JM, Sluka KA, Lauretti GR. High and low frequency TENS reduce postoperative pain intensity after laparoscopic tubal ligation: a randomized controlled trial. Clin J Pain. 2009b;25:12–19. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31817d1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSantana JM, Walsh DM, Vance C, Rakel BA, Sluka KA. Effectiveness of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for treatment of hyperalgesia and pain. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2008;10:492–499. doi: 10.1007/s11926-008-0080-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doig GS, Simpson F. Randomization and allocation concealment: a practical guide for researchers. J Crit Care. 2005;20:187–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2005.04.005. discussion 191-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egsgaard LL, Buchgreitz L, Wang L, Bendtsen L, Jensen R, Arendt-Nielsen L. Short-term cortical plasticity induced by conditioning pain modulation. Exp Brain Res. 2012;216:91–101. doi: 10.1007/s00221-011-2913-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmiler M, Solak O, Kocogullari C, Dundar U, Ayva E, Ela Y, Cekirdekci A, Kavuncu V. Control of acute postoperative pain by transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation after open cardiac operations: a randomized placebo-controlled prospective study. Heart Surg Forum. 2008;11:E300–E303. doi: 10.1532/HSF98.20081083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalra A, Urban MO, Sluka KA. Blockade of opioid receptors in rostral ventral medulla prevents antihyperalgesia produced by transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;298:257–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawchuk GN, Haugen R, Fritz J. A true blind for subjects who receive spinal manipulation therapy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90:366–368. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.08.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King EW, Audette K, Athman GA, Nguyen HO, Sluka KA, Fairbanks CA. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation activates peripherally located alpha-2A adrenergic receptors. Pain. 2005;115:364–373. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocyigit F, Akalin E, Gezer NS, Orbay O, Kocyigit A, Ada E. Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Effects of Low-frequency Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation on Central Pain Modulation: A Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Trial. Clin J Pain. 2012;28:581–588. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31823c2bd7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosek E, Ekholm J, Hansson P. Pressure pain thresholds in different tissues in one body region. The influence of skin sensitivity in pressure algometry. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1999;31:89–93. doi: 10.1080/003655099444597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus E, Le Bars D, Besson JM. Behavioral confirmation of "diffuse noxious inhibitory controls" (DNIC) and evidence for a role of endogenous opiates. Brain Res. 1981;206:495–499. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90554-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson JJ, McIlwrath SL, Woodbury CJ, Davis BM, Koerber HR. TRPV1 unlike TRPV2 is restricted to a subset of mechanically insensitive cutaneous nociceptors responding to heat. J Pain. 2008;9:298–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bars D, Dickenson AH, Besson JM. Diffuse noxious inhibitory controls (DNIC)I. Effects on dorsal horn convergent neurones in the rat. Pain. 1979;6:283–304. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(79)90049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leffler AS, Hansson P, Kosek E. Somatosensory perception in a remote pain-free area and function of diffuse noxious inhibitory controls (DNIC) in patients suffering from long-term trapezius myalgia. Eur J Pain. 2002;6:149–159. doi: 10.1053/eujp.2001.0312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leffler AS, Hansson P, Kosek E. Somatosensory perception in patients suffering from long-term trapezius myalgia at the site overlying the most painful part of the muscle and in an area of pain referral. Eur J Pain. 2003;7:267–276. doi: 10.1016/S1090-3801(02)00138-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard G, Cloutier C, Marchand S. Reduced analgesic effect of acupuncture-like TENS but not conventional TENS in opioid-treated patients. J Pain. 2011;12:213–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard G, Goffaux P, Marchand S. Deciphering the role of endogenous opioids in high-frequency TENS using low and high doses of naloxone. Pain. 2010;151:215–219. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebano RE, Rakel B, Vance CG, Walsh DM, Sluka KA. An investigation of the development of analgesic tolerance to TENS in humans. Pain. 2011;152:335–342. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lofgren M, Norrbrink C. Pain relief in women with fibromyalgia: a cross-over study of superficial warmth stimulation and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41:557–562. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moont R, Crispel Y, Lev R, Pud D, Yarnitsky D. Temporal changes in cortical activation during conditioned pain modulation (CPM), a LORETA study. Pain. 2011;152:1469–1477. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moont R, Crispel Y, Lev R, Pud D, Yarnitsky D. Temporal changes in cortical activation during distraction from pain: a comparative LORETA study with conditioned pain modulation. Brain Res. 2012;1435:105–117. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran F, Leonard T, Hawthorne S, Hughes CM, McCrum-Gardner E, Johnson MI, Rakel BA, Sluka KA, Walsh DM. Hypoalgesia in Response to Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) Depends on Stimulation Intensity. J Pain. 2011;12:929–935. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.02.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer ST, Martin DJ, Steedman WM, Ravey J. Effects of electric stimulation on C and A delta fiber-mediated thermal perception thresholds. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:119–128. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(03)00432-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantaleao MA, Laurino MF, Gallego NL, Cabral CM, Rakel B, Vance C, Sluka KA, Walsh DM, Liebano RE. Adjusting Pulse Amplitude During Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) Application Produces Greater Hypoalgesia. J Pain. 2011;12:581–590. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertovaara A. Experimental pain and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation at high frequency. Appl Neurophysiol. 1980;43:290–297. doi: 10.1159/000102268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platon B, Andrell P, Raner C, Rudolph M, Dvoretsky A, Mannheimer C. High-frequency, high-intensity transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation as treatment of pain after surgical abortion. Pain. 2010;148:114–119. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pud D, Granovsky Y, Yarnitsky D. The methodology of experimentally induced diffuse noxious inhibitory control (DNIC)-like effect in humans. Pain. 2009;144:16–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakel B, Cooper N, Adams HJ, Messer BR, Frey Law LA, Dannen DR, Miller CA, Polehna AC, Ruggle RC, Vance CG, Walsh DM, Sluka KA. A new transient sham TENS device allows for investigator blinding while delivering a true placebo treatment. J Pain. 2010;11:230–238. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabino GS, Santos CM, Francischi JN, de Resende MA. Release of endogenous opioids following transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation in an experimental model of acute inflammatory pain. J Pain. 2008;9:157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scales DC, Adhikari NK. Maintaining allocation concealment: following your SNOSE. J Crit Care. 2005;20:191–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherrer G, Imamachi N, Cao YQ, Contet C, Mennicken F, O'Donnell D, Kieffer BL, Basbaum AI. Dissociation of the opioid receptor mechanisms that control mechanical and heat pain. Cell. 2009;137:1148–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sluka KA, Deacon M, Stibal A, Strissel S, Terpstra A. Spinal blockade of opioid receptors prevents the analgesia produced by TENS in arthritic rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;289:840–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sluka KA, Walsh D. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation: basic science mechanisms and clinical effectiveness. J Pain. 2003;4:109–121. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2003.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowman PF, Wang K, Svensson P, Arendt-Nielsen L. Diffuse noxious inhibitory control evoked by tonic craniofacial pain in humans. Eur J Pain. 2011;15:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staud R, Robinson ME, Vierck CJ, Jr, Price DD. Diffuse noxious inhibitory controls (DNIC) attenuate temporal summation of second pain in normal males but not in normal females or fibromyalgia patients. Pain. 2003;101:167–174. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00325-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streff A, Michaux G, Anton F. Internal validity of inter-digital web pinching as a model for perceptual diffuse noxious inhibitory controls-induced hypoalgesia in healthy humans. Eur J Pain. 2011;15:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takakura N, Takayama M, Kawase A, Yajima H. Double blinding with a new placebo needle: a validation study on participant blinding. Acupunct Med. 2011;29:203–207. doi: 10.1136/aim.2010.002857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong KC, Lo SK, Cheing GL. Alternating frequencies of transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation: does it produce greater analgesic effects on mechanical and thermal pain thresholds? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88:1344–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tousignant-Laflamme Y, Marchand S. Excitatory and inhibitory pain mechanisms during the menstrual cycle in healthy women. Pain. 2009;146:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva L. Diffuse Noxious Inhibitory Control (DNIC) as a tool for exploring dysfunction of endogenous pain modulatory systems. Pain. 2009;143:161–162. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva L, Bouhassira D, Le Bars D. The medullary subnucleus reticularis dorsalis (SRD) as a key link in both the transmission and modulation of pain signals. Pain. 1996;67:231–240. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(96)03121-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen YR, Wang CC, Yeh GC, Hsu SF, Huang YJ, Li YL, Sun WZ. DNIC-mediated analgesia produced by a supramaximal electrical or a high-dose formalin conditioning stimulus: roles of opioid and alpha2-adrenergic receptors. J Biomed Sci. 2010;17:19. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-17-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarnitsky D, Crispel Y, Eisenberg E, Granovsky Y, Ben-Nun A, Sprecher E, Best LA, Granot M. Prediction of chronic post-operative pain: pre-operative DNIC testing identifies patients at risk. Pain. 2008;138:22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarnitsky D, Ochoa JL. Studies of heat pain sensation in man: perception thresholds, rate of stimulus rise and reaction time. Pain. 1990;40:85–91. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(90)91055-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]