Abstract

Aberrant changes in post-translational modifications (PTMs) such as phosphorylation underlie a majority of human diseases. However, detection and quantification of PTMs for diagnostic or biomarker applications often requires monoclonal PTM-specific antibodies, which are challenging to generate using traditional antibody-generation platforms. Here we outline a general strategy for producing synthetic PTM-specific antibodies by engineering a motif-specific ‘hot spot’ into an antibody scaffold. Inspired by a natural phosphate-binding motif, we designed antibody scaffolds with hot spots specific for phosphoserine, phosphothreonine, or phosphotyrosine. Crystal structures of the phospho-specific antibodies revealed two distinct modes of phosphoresidue recognition. Our data suggest that each hot spot functions independently of the surrounding scaffold, as phage display antibody libraries using these scaffolds yielded >50 phospho- and target-specific antibodies against 70% of target peptides. Ultimately, our motif-specific scaffold strategy may provide a general solution for the rapid, robust development of monoclonal anti-PTM antibodies for signaling, diagnostic and therapeutic applications.

Introduction

PTMs, such as phosphorylation, acetylation, and ubiquitination, have essential roles in modulating protein function throughout biology. In particular, phosphorylation is one of the most common regulatory mechanisms in eukaryotes; ~20–30% of all eukaryotic proteins can be phosphorylated by >500 kinases1. Given the ubiquitous role of phosphorylation in signal transduction, it is not surprising that aberrant phosphorylation either directly causes or is a consequence of many human diseases, such as cancer and neurodegenerative disorders2. Recent advances in phosphoproteomic methods have greatly expanded the number of known phosphorylation sites (>170,000) and identified global phosphorylation changes that occur during disease3–6. Ultimately, the validation of key phosphorylation events is best conducted at the single-cell level. Recent single-cell studies using phospho-specific (PS) monoclonal antibodies (Abs) have elucidated how stochastic fluctuations and signaling cross-talk contribute to the overall cellular state7, 8. Unfortunately, very few commercially available Abs are suitable for this purpose7, and given the steady increase in the number of functionally important phosphorylation sites, there is a need for a rapid, robust method to generate high-quality, renewable, monoclonal PS detection reagents. Renewable, recombinant Abs would also provide genetically encoded functional tools for cell biology.

The state of the art in PS detection reagents is the generation of Abs by the immunization of animals9. However, the generation of a polyclonal PS Ab is often imprecise, low-throughput, expensive, time-consuming and not renewable. Furthermore, the development of monoclonal PS antibodies requires additional screening of numerous hybridomas, which is made more challenging by the rarity of PS Ab clones, estimated to be 0.1–5%10, 11. Finally, disproportionately more phosphotyrosine (pTyr)-specific Abs exist than phosphoserine (pSer)- or phosphothreonine (pThr)-specific Abs. This fact has hindered the study of serine and threonine phosphorylation, which account for 90% and 10% of all phosphorylation sites, respectively, compared with <0.05% for tyrosine12. Unfortunately, attempts to generate recombinant PS Abs using in vitro selection methods, such as phage display13–17, yeast display18, and ribosome display19, have been even less efficient than immunization methods18, 20–22. Engineered endogenous phosphopeptide-binding domains such as Src-homology-2 (SH2) or forkhead-associated (FHA) domains may provide an alternative to Abs, but the general utility of these scaffolds remains to be demonstrated23–25.

Recently, the combination of immunization and phage display was used to isolate a high-affinity PS Ab from chickens21. Although this approach was successful and led to the first PS Ab structure, it relies upon a low-throughput and time-consuming immunization step. We hypothesize that both immunization and in vitro methods for generating PS Abs fail to routinely yield high-quality Abs because most naïve Abs do not possess any initial affinity for the small peptide antigens. In light of these difficulties, we envisioned a structure-guided strategy for generating Abs that employs Ab scaffolds with engineered pockets tailored to a particular sequence motif. This motif-specific anchoring pocket would provide initial antigen-binding affinity and guide the selection of Abs targeted to epitopes containing the motif (e.g. a pSer- or pTyr-containing peptide). These motif residues, known as ‘hot spots’, contribute a substantial fraction of the binding energy to a protein-protein interaction26, 27

Here we engineer Ab scaffolds with designed binding pockets for pSer, pThr or pTyr residues and thereby make these residues hot spots in the antigen-Ab interaction. Guided by a natural phosphate-binding motif and knowledge of Ab structure-function, we first identified a parent Ab scaffold in which to install the designed pocket in the complementarity-determining regions (CDRs). We then mutated the scaffold to specifically bind pSer, pThr or pTyr and solved the X-ray crystal structures of PS Ab:peptide complexes. In the second step, we constructed two large diverse single-chain Fv (scFv) Ab phage display libraries based upon these scaffolds and successfully selected 51 PS Abs against seven different pSer- or pThr-containing peptides. These results suggest that the phosphoresidue-binding pocket functions independently of additional structural and functional changes in other CDRs of the Ab.

Results

Design of PS Ab scaffolds

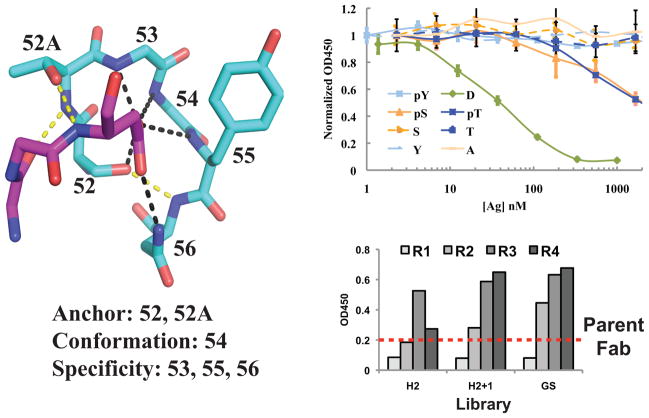

To design a phosphate-binding motif into an Ab scaffold, we drew upon structural knowledge of how protein domains recognize anions, such as phosphate. The most common anion-binding motif, called a nest, occurs within many different protein super-families, such as ATPases and kinases, and consists of three consecutive residues where multiple main-chain amides form hydrogen bonds with the anion (Supplementary Fig. 1a)28. Starting with this ubiquitous motif, we sought to find an existing Ab scaffold into which we could build a similar short, localized loop. We focused our search on sixty anti-peptide Ab structures and manually inspected the CDRs for the desired nest conformation. We identified a region of CDR H2 within a mouse Fab (PDB ID 1i8i)29 that adopts the desired conformation due to a hallmark αL glycine at 54H (Fig. 1a). Notably, this Ab uses the H2 loop to bind an acidic residue via six loop residues that anchor the peptide (52H and 52AH), stabilize the conformation (54H), or confer side chain specificity (53H, 55H, and 56H) (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Table 1). A larger search of all Ab-antigen structures identified eight Abs that use this loop to bind an aspartate or glutamate in the antigen (Supplementary Fig. 1b).

Figure 1.

Design of phospho-specific Ab scaffold. a) Structure of CDR H2 loop from Ab (PDB ID 1i8i) bound to aspartate in peptide antigen31. Each H2 residue contributes to anchoring the peptide (52H and 52AH), specificity (53H, 55H, and 56H), or conformation (53H). Hydrogen bonds that confer specificity are shown in black and anchoring hydrogen bonds are shown in yellow. The peptide is shown in magenta and Ab heavy chain is shown in cyan. b) Competition phage ELISAs with humanized Fab. Eight different mutant peptides containing D, A, S, T, Y, pS, pT, or pY at position 8 of the peptide were used as soluble competitors to inhibit Fab-phage binding to the immobilized wild-type peptide (KGNYVVTDH) (n=3, error bars represent standard deviation). Strong competition was observed for the wild-type peptide (green line), whereas no competition was observed for the S, T, A, or Y peptides (dashed lines) indicating that D is a hot-spot residue. Notably, the Fab binds to phosphorylated species as weak competition was observed for the pSer and pThr peptides (orange and blue solid lines, respectively). c) Representative pooled phage ELISAs from selection of H2-targeted library against pSer peptide. After three rounds of selection, all library pools exhibited higher binding signal to the pSer peptide than the parent Fab (dashed line).

To characterize this class of Ab-antigen interactions, we synthesized the gene encoding a humanized version of the 1i8i Fab and cloned this construct into both a phage display and protein expression vector (Supplementary Table 2). The humanized scaffold, which expressed at yields > 3mg/L in bacteria, bound the peptide with similar affinity as reported for the mouse Fab29. To understand the importance of the Asp-loop (residues 52H–56H) interaction in peptide binding, we performed competition phage ELISAs to analyze Fab binding to a panel of peptides. ELISA data confirmed that the Asp8 residue of the antigen is a hot spot for binding as mutation to Ala, Ser, Thr, or Tyr substantially reduced Fab binding (>100-fold less) to the peptide (Fig. 1b). We reasoned that the carboxylate group of Asp8 residue might mimic a phosphorylated residue and thus, the Ab may bind peptides with pSer, pThr, or possibly pTyr in place of Asp8. ELISA data confirmed the ability of this Fab to bind pSer- or pThr-containing peptides, albeit with weak affinities (>2000 nM) (Fig. 1b and Table 1). No Ab binding was observed to the pTyr peptide probably owing to its large size. Structural analysis of the peptide:Fab complex suggested that steric clashes with several side chains and the main chain of the CDR were likely responsible for the weak affinities.

Table 1.

Affinity measurements of Ab scaffolds as determined by Biacore.

| Fab | Peptide | kon (M−1 s−1) | koff (s−1) | KD (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent | WT Asp | 3.38 × 105 | 0.0032 | 9.6 |

| pSer | n.d. | n.d. | >2000a | |

| pThr | n.d. | n.d. | >2000a | |

| Ser/Thr | n.d. | n.d. | >2000a | |

| pSAb | pSer | 1.0 × 105 | 0.0075 | 71 |

| pThr | 4.7 × 104 | 0.041 | 866 | |

| Ser/Thr | n.d. | n.d. | >2000a | |

| pSTAb | pSer | 4.8 × 104 | 0.0082 | 172 |

| pThr | 2.8 × 104 | 0.0064 | 232 | |

| Ser/Thr | n.d. | n.d. | >2000a | |

| pYAb | pTyr | 1.9 × 105 | 0.070 | 360 |

| Tyr | 2.84 × 104 | 0.249 | 8700 |

No binding seen by competition ELISAs. Peptide sequences for WT, pSer, pThr, and pTyr are GEKKGNYVVTDH, GEKKGNYVVTpSH, GEKKGNYVVTpTH, and GEKKGNYVVTpYA, respectively.

Therefore, we constructed three Ab phage display libraries to optimize the CDR region for each phosphorylated residue. The six-residue CDR region (52H–56H) was replaced with six random residues (H2 library) or seven random residues (H2+1 library) to relieve steric clashes with the Ab backbone. The third library design was similar to the H2 library, but fixed Gly or Ser at 53H and 54H (GS library). These strategies allowed us to assess the importance of the anchor (52H and 52AH) and conformation (55H) residues as well as alter the specificity residues (53H, 55H, and 56H). Using standard phage display methods, we then performed four rounds of selection against pSer, pThr, and pTyr peptides. Notably, we observed strong enrichment against each of the pSer, pThr, and pTyr peptide targets using all three libraries, except for selections with the H2+1 library against pTyr (Fig. 1c and data not shown).

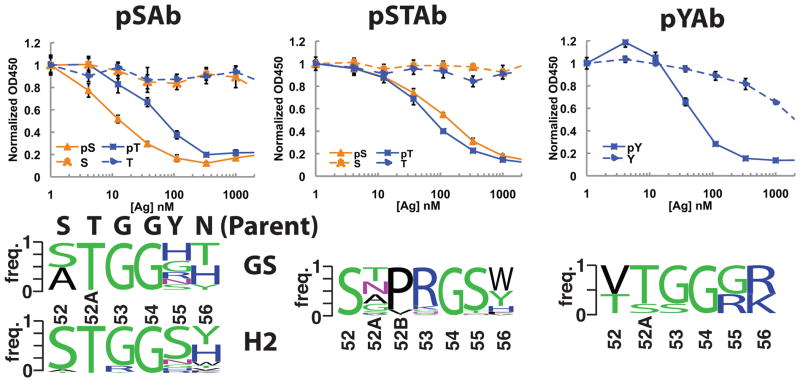

Characterization of PS Ab scaffolds

For each phosphopeptide antigen, we isolated single phage clones and sequenced the CDR H2 region for clones that bound to the phosphopeptide by single-point ELISA (data not shown). Selections against the pSer and pThr peptides gave similar sequences and thus were combined into one sequence logo. Sequence logos from the H2- and GS-library selections against pSer/pThr highlighted the conservation of the key anchoring residue T52AH and conformation residue G54H in the loop, whereas more diversity was observed in the specificity residues (55H and 56H) (Fig. 2a). Notably, in the H2+1 libraries, we observed a strong enrichment for a Pro-Arg insertion in place of G53H and conservation of G54H (Fig. 2b). The G54H residue occupies a region of the Ramachandran plot in which only glycine is allowed, thus suggesting that this glycine is critical for the conformation29–31. The pTyr Abs contained a different binding motif from the pSer/pThr Abs suggesting that the mode of pTyr recognition differs from that of pSer/pThr recognition (Fig. 2c).

Figure 2.

Selection and characterization of pSer-, pSer/pThr-, and pTyr-specific scaffolds. Competition ELISAs were used to determine the specificity of each Ab scaffold (n=3, error bars represent standard deviation). For both pSAb (a) and pSTAb (b), no binding inhibition was observed for the unphosphorylated peptides up to 2 μM, whereas strong inhibition was observed for the phosphorylated peptides. For pYAb (c), weak inhibition was observed at high concentrations of the unphosphorylated Tyr peptide, but ~20-fold less pTyr peptide was required to observe the same level of inhibition. The sequence frequency logos of the Ab pools from which each lead clone was derived are depicted in the bottom panels. GS and H2 indicate the sequence logos from GS and H2 libraries selected against pSer and pThr. For the six-residue loops selected for pSer or pThr binding, clear enrichment for the G53H and G54H is seen. For the seven-residue loops selected for pSer or pThr binding, we observed a replacement of G53H with Pro-Arg, likely opening up the binding pocket to better accommodate pThr. All clones that bound pTyr came from the six-residue libraries and contain two positively charged amino acids at H55 and H56. The H2 sequences of pSAb, pSTAb, and pYAb are ATGGHT, STPRGST, and VTGGRK, respectively.

Next, we analyzed the phage clones by competition ELISA to identify the best scaffold for each target (pSer, pThr, or pTyr) (data not shown). We identified a pSer-specific scaffold (pSAb with sequence ATGGHT), a pSer/pThr-specific scaffold (pSTAb with sequence STPRGST), and a pTyr-specific scaffold (pYAb with sequence VTGGRK). We were unable to isolate a pThr scaffold that did not cross-react with the pSer peptide. To determine the phospho-selectivity of these scaffolds, we analyzed binding to the phosphorylated and unphosphorylated peptides by ELISA and Biacore. Strikingly, we observed high affinity and selectivity for the phosphorylated peptide in all cases (Fig. 2 and Table 1).

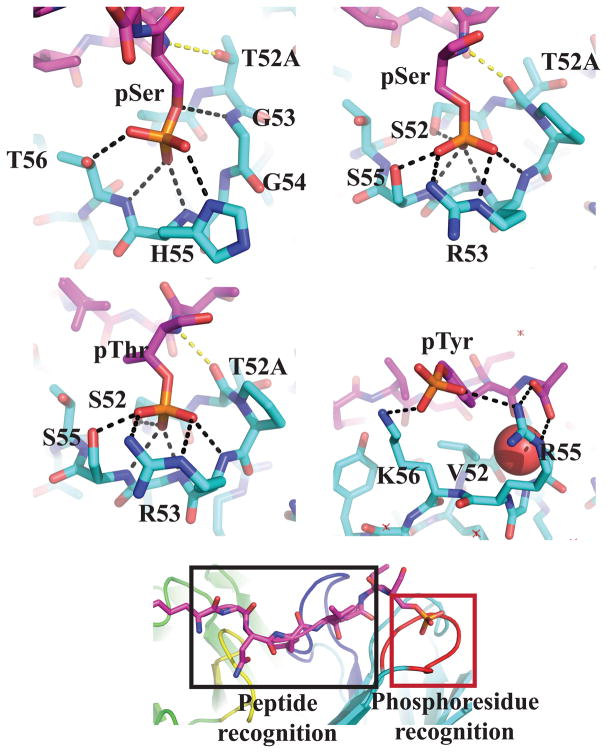

Structural analysis of phosphopeptide recognition

To explore the mode of phosphoresidue recognition, we determined the X-ray structure of four Fab:peptide complexes (pSAb:pSer, pSTAb:pSer, pSTAb:pThr, and pYAb:pTyr) as well as the unbound pYAb Fab (Supplementary Table 4 and 5). We observed strong electron density for the bound peptide in all pSer and pThr structures (Supplementary Fig. 3). For the pYAb Fab, only one of the two Fab copies in the asymmetric unit was fully occupied by the peptide, likely due to the packing arrangement of the Fabs (Supplementary Fig. 3). No changes in the positions of the CDRs were observed between the mouse29 and humanized Abs (cα RMSD of 0.78 Å). Furthermore, binding of the peptide to the Ab did not induce any major CDR movements (cα RMSD of 1.3 Å) (Supplementary Fig. 4). For all phosphopeptides, the recognition is achieved through two sectors: the phosphoresidue-binding pocket and a neighboring peptide sequence ‘reader’ region, which consists primarily of CDRs L3 and H3 (Fig. 3e). Additionally, all peptide:Ab contacts outside of the phosphoresidue also occur in the parent Fab (Supplementary Fig. 4c)29.

Figure 3.

X-ray crystal structures of phosphoresidue-binding pocket from pSAb (a), pSTAb (b and c), and pYAb (d). a) In pSAb, pSer makes hydrogen bonds with all three specificity residues (G53H, H55H and T56H). The anchoring hydrogen bond (yellow) to T52AH is conserved. b and c) In pSTAb, the pSer/pThr makes hydrogen bonds with two specificity residues (R53H and S55H), one anchor residue (S52H), and the conformation residue (G54H). In both pSTAb structures bound to pSer and pThr, R53H forms a bidentate interaction with the phosphate. The anchor residue T52AH is flipped compared to pSAb, which allows the backbone carbonyl to make a new anchoring hydrogen bond (yellow). d) The pTyr is recognized by a salt bridge with K56H and a hydrophobic interaction between V52H and the phenyl ring of the pTyr. However, the phosphate group of pTyr does not occupy the phosphate-binding pocket, which is instead occupied by a water molecule (shown as red sphere). e) The structures demonstrate two distinct recognition sectors: a phosphoresidue-binding pocket (red box) and the peptide-binding “reader” region (black box). Key CDRs L3, H2, and H3 are colored yellow, dark blue, and red. Phosphopeptides are shaded magenta and the Ab light and heavy chains are shaded green and cyan, respectively. Yellow and black dashed lines indicate hydrogen bonds between the phosphoresidue and Ab scaffold.

Structures of the peptide:Fab complexes illustrate how CDR H2 specifically recognizes each phosphoresidue (Fig. 3). For all three scaffolds, mutations found in the parent H2 loop make the main chain more accessible, creating a large electropositive binding pocket (indicated by arrow in Supplementary Fig. 5). The phosphoresidue side chain is almost fully engulfed by the Ab in pSAb (80% buried) and pSTAb (92% buried) and anchored by multiple hydrogen bonds (Fig. 3a–c, and Supplementary Table 6). In pSAb, the pSer residue makes key contacts with specificity residues G53H, R55H, and T56H, whereas in pSTAb, the pSer and pThr residues make key contacts with R53H, G54H, and S55H. In pSTAb, the insertion of P52BH allows the T52AH anchor to flip out and still contribute a hydrogen bond from the main-chain carbonyl. In stark contrast, pYAb does not use the original designed loop conformation to bind pTyr (Fig. 3d). A key ionic interaction with K56H and a hydrophobic interaction with V52H contribute to the recognition mode. Notably, the H2 nest pocket is occupied by a water molecule that is stabilized by the free C-terminus of the peptide, indicating that pYAb may bind differently to the pTyr residue in longer peptides without this neighboring free carboxylate (Fig. 3d). Combined, our in vitro characterization and X-ray crystal structures confirmed that we successfully designed novel Ab scaffolds that use pSer, pThr, or pTyr as hot-spot residues.

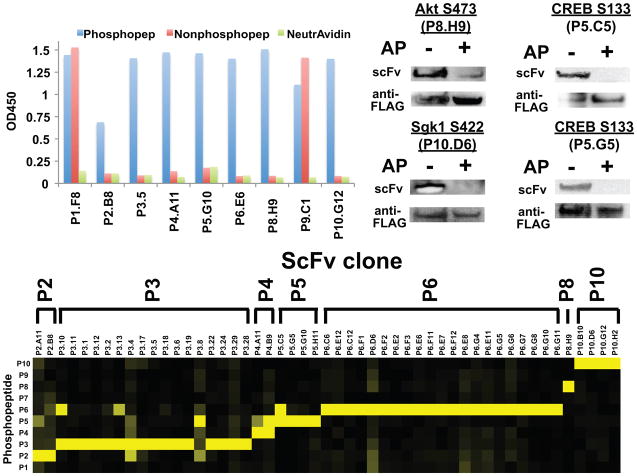

Generation of PS Abs using the pSer and pSer/pThr scaffolds

We hypothesized that an Ab library in which the phosphoresidue-binding pocket was conserved and ‘reader’ regions were mutated would enable rapid generation of new PS Abs. Because every member of the initial library contains a phosphoresidue-binding pocket, each Ab should have a weak initial affinity for the phosphorylated antigen, dramatically enhancing the selection of new Abs. As a proof of principle, we targeted pSer- and pThr-containing antigens, as reagents capable of detecting these modifications are significantly lacking. We diversified surface-exposed positions in CDR H2 (50H, 56H, and 58H) outside of the phosphate-binding pocket, CDR H3 (95H–101H), and CDR L3 (91L–94L, 96L) (Supplementary Table 7).

We chose a set of ten biologically relevant pSer- or pThr-containing epitopes as target antigens (Table 2). As a stringent test, we did not perform counter-selections against the unphosphorylated antigens, since we reasoned that the binding pocket could be sufficient for selection of Abs that required the phosphorylated residue. We performed three rounds of selection and analyzed single phage clones from the third round of selection by single-point ELISA. Impressively, for seven targets, we isolated at least one scFv that bound only to the phosphorylated antigen (Table 2 and Fig. 4a). To demonstrate the specificity of the isolated clones, we performed a panel of ELISAs to assay binding of each scFv to each of the ten phosphorylated peptides (Fig. 4b). The data demonstrated the exquisite target selectivity of most scFv clones, indicating the absence of promiscuous pSer-/pThr-peptide binding scFvs. Western blot analysis confirmed that a sample set of Abs specifically recognized the corresponding phosphoprotein (Fig. 4c). Finally, the scFv-Fc fusions exhibited affinities ranging from 42 to 2430 nM (Table 2), which matches or exceeds previous reports of PS Ab affinities18, 21.

Table 2.

Summary of scFv hits versus ten new phosphopeptide targets.

| Peptide | Sequence | Number of unique scFvs | Number of phosphospecific scFvsa | KD (nM)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1: Caspase 3 (S12) | NTENSVDSKpSIKNLEPKII | 5 | 0 | n.d. |

| P2: RIPK3 (S227) | REVELPTEPpSLVYEAV | 6 | 2 | 102 ± 15 (P2.A11) |

| P3: RIPK3 (S199) | LFVNVNRKApST ASDVYSF | 23 | 17 | 250 ± 13 (P3.28) |

| P4: Smad2 (T8) | MSSILPFpTPPVVKRLL | 3 | 2 | 78 ± 14 (P4.B9) |

| P5: CREB (S133) | RREILSRRPpSYRKILNDL | 4 | 4 | 151 ± 8 (P5.G10) |

| P6: HtrA2 (S212) | RRRVRVRLLpSGDTYEAVV | 21 | 21 | 2430 ± 150 (P6.C12) |

| P7: Akt1 (T308) | KEGIKDGATMKpTF | 0 | 0 | n.d. |

| P8: Akt1 (S473) | ERRPHFPQFpSYSASGTA | 1 | 1 | >5000c (P8.H9) |

| P9: PKC Θ (S695) | DQNMFRNFpSFMNPGMER | 1 | 0 | n.d. |

| P10: Sgk1 (S422) | EAAEAFLGFpSYAPPTDSF | 4 | 4 | 42.2 ± 2.8 (P10.D6) |

scFv clones that exhibited >5-fold higher ELISA signal against phosphorylated peptide compared to unphosphorylated peptide (Fig. 4).

As determined by competition ELISA with scFv-Fc protein (n = 2–3, error values represent standard deviation). Clone ID is shown in parentheses.

Only partial competition was observed at the concentrations of peptide used.

Figure 4.

Generation of recombinant phospho-specific (PS) Abs using the pSAb and pSTAb scaffolds. a) Representative phage ELISAs of one scFv clone selected against each of the nine phosphopeptide targets demonstrates that we selected PS Abs to seven out of the ten targets. No hits were observed against P7. To analyze target specificity, we characterized the binding of each scFv-phage to ten different phosphopeptides by phage ELISA (n = 2 – 3) (b). Heatmap representation of the phage ELISA binding signals for each scFv-phage (vertical axis) against each of the ten phosphopeptides (horizontal axis). Strikingly, most of these scFvs bind only to the phosphopeptide against which they were selected. For each scFv, signals were normalized to the highest overall ELISA signal observed against the ten peptides. The scale goes from zero (black) to one (yellow). c) ScFvs also recognize the phosphorylated protein in Western blots. FLAG-tagged target proteins were immunoprecipitated from transiently transfected HEK293T. To verify PS binding, samples were either dephosphorylated using alkaline phosphatase (AP) or treated with buffer only. Membranes were probed with biotinylated scFv (20 μg/mL) overnight and bound scFv was detected using NeutrAvidin-HRP. Total levels of target protein were monitored using anti-FLAG-HRP (Supplemental Methods).

Discussion

Here we describe a novel, recombinant Ab generation method that entails the design of a motif-specific (e.g. pSer, pThr, or pTyr) Ab scaffold followed by structure-informed mutagenesis of the scaffold to generate monoclonal Abs against a panel of phosphopeptide antigens. The high success rate of our strategy (PS Abs against 7 of 10 targets), which does not employ counter-selections against the unphosphorylated epitope, demonstrates how the motif-specific pocket greatly improves the selection process, as even past Ab libraries generated from immunized animals required stringent counter-selections to enrich for PS Abs21, 22. In the case of pSAb and pSTAb, the pocket contains a hallmark αL glycine at 54H that contributes to the main-chain conformation of CDR H2. There is a very high frequency of occurrence for this H2 conformation in Abs (~12% of all H2 conformations31), and multiple Ab structures with anionic molecules (e.g. aspartate, glutamate, or sulfate) bound at this site (Supplementary Fig. 1).

While our studies were in progress, the structure of a chicken scFv, which was generated from an immunized phage display library, was reported that used a similar H2 conformation to bind pThr-containing phosphopeptide21. Notably, a structural comparison of this chicken scFv with our Abs reveals that the phosphoresidue binds to the same H2 loop conformation albeit with a different hydrogen bonding pattern (Supplementary Fig. 7). This striking similarity suggests there may be a germline-encoded anion-binding pocket capable of binding phosphate or sulfate groups. In fact, previous work on Abs that bind phospholipids suggested a ‘phosphate-binding subsite’ that conferred recognition of only the phosphorylated or sulfated forms of multiple lipids and haptens32. Furthermore, anion-binding pocket-containing Abs may provide a protective role in the recognition of phosphorylated or sulfated antigens, such as lipid A in Gram-negative bacteria32, or conversely, a more sinister role in autoimmune diseases, such as antiphospolipid syndrome33. Future crystallographic studies of these Ab:antigen complexes will illuminate this possibility.

Interestingly, the main-chain dominated mode of pSer/pThr recognition is completely different from most endogenous pSer/pThr-binding domains such as SH2, 14-3-3, and FHA, which predominantly use side chains to bind the phosphoresidue34 (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 6). Only the WW domain sometimes uses two main-chain amides to bind a phosphate. In fact, our pSer/pThr scaffolds bind more efficiently to the phosphoresidue than naturally occurring domains by burying a larger surface area and contributing more hydrogen bonds (Supplementary Table 6). It was recently suggested that these endogenous phosphoresidue-binding and other PTM-binding domains have evolved to bind shorter epitopes with moderate affinities to support the dynamic nature of signal transduction pathways, which potentially limits the range of epitopes they can bind34–36. Additionally, our designed PS pockets appear to function independently of the other CDRs as we could diversify those CDRs to target highly diverse phosphopeptides (Fig. 4).

Surprisingly, pYAb uses a completely different motif to recognize pTyr. It is notable that we achieved highly specific recognition of pTyr, despite not burying most of the pTyr phenyl ring (Fig. 2c and 3d). However, we have yet to determine how the presence of the free carboxylate, which stabilizes a water molecule in the nest, contributes to the binding affinity. We are currently developing new scaffolds in which most of the pTyr residue is buried and bound in a more nest-like region to boost the ligand efficiency and affinity.

Our bacteriophage-derived PS Ab platform, which can be automated, rapidly generates Abs within two weeks as opposed to the several months required for hybridoma methods. In stark contrast to traditional monoclonal or polyclonal PS Abs, our recombinant PS Abs use a single framework that permits high-level bacterial expression (> 3mg/L) and mammalian expression (~0.5–5 μg/mL media) in a renewable format. The use of a single framework greatly simplifies mutagenesis protocols (e.g. affinity maturation), sequence-function analysis, and conversion to other Ab formats (e.g. IgG).17 Finally, we hypothesize that this motif-specific scaffold method should be generalizable to targeting virtually any antigen with a defined motif. Since many other PTM-binding motifs exist in nature, these motifs may be similarly designed into Abs to generate high-affinity monoclonal reagents capable of detecting other PTMs. Ultimately, the rapid in vitro generation of monoclonal anti-PTM antibodies will greatly enhance the study of PTMs throughout biology.

Methods

Vector Construction

We constructed a series of p3 phage display vectors along with compatible protein expression vectors (Supplementary Table 2). We modified the human Fab template by Kunkel mutagenesis, according to standard protocols37. All restriction enzymes and DNA polymerases were purchased from NEB (Ipswich, MA). Oligonucleotides were purchased from IDT and all constructs were verified by DNA sequencing (Quintara Biosciences).

Generation of Phage Libraries

A humanized Fab in pJK1 with two stop codons within the CDR H2 was used as a template for Kunkel mutagenesis with oligonucleotides designed to correct the stop codons and introduce the designed mutations at each site17, 37. To make the H2-targeted libraries, we generated three libraries in which the codons encoding for the parent H2 sequence (STGGYN) was replaced with either i) six random amino acids encoded by NNK (H2 library), ii) seven random amino acids encoded by NNK (H2+1 library), or iii) a core set of two or three amino acids, which were allowed to be only Gly or Ser, and were flanked on both sides by two random amino acids encoded by NNK (GS library). Mutagenic oligonucleotides are listed in Supplemental Table 3. The resulting mutagenesis reactions were electroporated and phage were produced as previously described17. The final diversities of the H2, H2+1, and GS libraries were 6.5 × 109, 1.6 × 1010, and 5.3 × 109, respectively.

To make the PS Ab libraries, we constructed two scFv templates, which consisted of either the pSAb or pSTAb variable light chain linked to the corresponding variable heavy chain by a (Gly4Ser)3 linker and contained two stop codons in the CDR H3. These plasmids were then used as templates for Kunkel mutagenesis. The light chain CDR L3 (91L-94L, 96L) and the heavy chain CDR H2 (50H, 56H, and 58H) were diversified using degenerate codons designed to mimic the natural sequence diversity found at these positions (Supplemental Table 7)17, 38. CDR H3 was diversified using three to nine random amino acids (DVK) followed by three terminal residues (F/M, A/D, and Y) commonly observed in anti-peptide Abs. For the mutagenesis reactions, L3 oligonucleotides (P1 and P2) were mixed at a 1:1 molar ratio, H2 oligonucleotides (1, 2, and 3) were mixed at a 0.1:1:2 ratio and H3 oligonucleotides (PX.1 and PX.2, where X = CDR length) were mixed at a 2:1 ratio. The resulting libraries were produced using Hyperphage39 to enhance recovery of rare binders and the final diversities of the pSAb and pSTAb libraries were 3.4 × 1010 and 2.7 × 1010, respectively.

Phage Display Selections, ELISAs, and Western blots

All phage preparations, selections, and ELISAs were performed according to standard protocols (Supplemental Methods)17. Western blots with biotinylated scFvs were performed as described in Supplemental Methods.

Protein Expression and Purification

Selected Fabs were expressed in a protease-deficient C43 strain40. Expressed Fabs were purified from total cell lysates by Protein A, ion exchange, and gel filtration chromatography as previously described17, 38. Fabs were stored at 4°C for short-term analysis or flash frozen in 10% glycerol for storage at −80°C. ScFv-rFc constructs were transiently transfected into 293T cells and purified from the media using Protein A chromatography. Biotinylated scFvs contained a C-terminal biotin acceptor peptide and were co-expressed with BirA to enzymatically biotinylate each protein (pJK5). Nonphosphorylated versions of all peptides were fused to the C-terminus of NusA, which contained an N-terminal His6 tag and biotin acceptor peptide. Recombinant proteins were purified on a His GraviTrap column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) followed by monomeric Avidin resin (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) to a final purity of >95%. All biotinylated peptides were purchased from Elim Biopharmaceuticals (Hayward, CA) or Peptibody, Inc. (Charlotte, NC).

Biacore Analysis

Surface plasmon resonance data was measured on a Biacore model 4000 (Biacore, Uppsala, Sweden). All proteins were in TBS containing 0.1mg/mL BSA and 0.01% Tween-20. A Biacore CM5 chip was coated with NeutrAvidin at ~3000 RU and biotinylated antigens were captured at <100 RU. Serial dilutions of the Fabs were flowed over the immobilized antigens and 1:1 Langmuir binding models were used to calculate the kon, koff, and KD for each Fab:antigen pair.

Crystallization of peptide:Fab complexes

Fabs were expressed as described above and concentrated to 10–15 mg/mL in 10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl. Complexes of the Fab with the corresponding peptide were formed at a 1:2 molar ratio of Fab:peptide. Crystals were grown in hanging drop format by mixing 100 nL protein solution and 100 nL crystallization solution using a Mosquito nanoliter pipetting system (TTP Labtech). Crystals formed within one to two weeks at either 18°C or 4°C. Initially, the crystals we obtained for the Fabs bound to the pSer peptides diffracted very weakly. We therefore employed a microseeding strategy with a seed stock generated from finely ground pSTAb:pThr crystals in 50 uL cryoprotectant solution41. Crystals for the pSAb:pSer and pSTAb:pSer complexes were generated by hanging drop vapor diffusion with 300 nL drops consisting of 150 nL protein solution, 120 nL reservoir solution, and 30 nL 1:100 dilution of seed stock. All crystals were soaked in cryoprotectant solution and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Crystallization conditions and cryoprotectant solutions are listed in Supplementary Table 4.

Diffraction data were collected using the Advanced Light Source beam line 8.3.1 at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley, California) with a wavelength of 1.1 Å. The data were indexed, integrated, and scaled using ELVES42 or HKL200043. The structure of the pSTAb:pThr complex was solved by molecular replacement using Phenix44. The initial search model consisted of the variable heavy domain from 3n9g and the variable light domain, constant heavy domain, and constant light domain from 2gcy45. The pSTAb Fab structure was used as the search model for all other structures. Iterative rounds of model building and refinement were carried out with Phenix and Coot46. For isomorphous crystals, the same refinement test sets for calculating Rfree were used. Simulated annealing composite omit maps calculated using Phenix were used to remove model bias. After two rounds of refinement, peptides were built into each model using Coot. Riding hydrogens as implemented in Phenix were used in the final stages of refinement for the pSAb:pSer, pSTAb:pSer, and pSTAb:pThr complexes. Final refinement statistics can be found in Supplementary Table 5. The final coordinates were validated using MolProbity47. The final Ramachandran statistics (% Favored:% Outlier) were 98:0.2, 98:0.2, 98:0.2, 98:0, and 97:0.2 for pSAb:pSer, pSTAb:pSer, pSTAb:pThr, pYAb:pTyr, and pYAb, respectively. MacPyMol (DeLano Scientific) was used to generate structure figures. Electrostatic surfaces were calculated using APBS48 and buried surface areas were calculated using CCP449.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Wells lab for helpful discussions regarding this manuscript and Sam Pfaff for assistance with Biacore experiments. We thank Chris Waddling at the UCSF X-ray facility for assistance with generating protein crystals and James Holton, George Meigs, and Jane Tanamachi at the Advanced Light Source beam line 8.3.1 at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory for help with collection of diffraction data. We thank the Court lab at the National Institutes of Health for generously providing the recombineering vectors. James Koerber is a Fellow of the Life Sciences Research Foundation and Nathan Thomsen is the Suzanne and Bob Wright Fellow of the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Heath (R01 CA154802 to JAW and GM54616 to WFD). JTK, JAW, and WFD have filed a provisional patent on the technology described in this manuscript.

Footnotes

Accession code

The X-ray coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank for pSAb:pSer, pSTAb:pSer, pSTAb:pThr, pYAb:pTyr, and pYAb with accession IDs 4JFZ, 4JG0, 4JG1, 4JFX, and 4JFY, respectively.

References

- 1.Cohen P. The regulation of protein function by multisite phosphorylation--a 25 year update. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:596–601. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01712-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blagoev B, Ong SE, Kratchmarova I, Mann M. Temporal analysis of phosphotyrosine-dependent signaling networks by quantitative proteomics. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:1139–1145. doi: 10.1038/nbt1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou H, Watts JD, Aebersold R. A systematic approach to the analysis of protein phosphorylation. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:375–378. doi: 10.1038/86777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hornbeck PV, Chabra I, Kornhauser JM, Skrzypek E, Zhang B. PhosphoSite: A bioinformatics resource dedicated to physiological protein phosphorylation. Proteomics. 2004;4:1551–1561. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beausoleil SA, et al. Large-scale characterization of HeLa cell nuclear phosphoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:12130–12135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404720101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bendall SC, et al. Single-cell mass cytometry of differential immune and drug responses across a human hematopoietic continuum. Science. 2011;332:687–696. doi: 10.1126/science.1198704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sachs K, Perez O, Pe’er D, Lauffenburger DA, Nolan GP. Causal protein-signaling networks derived from multiparameter single-cell data. Science. 2005;308:523–529. doi: 10.1126/science.1105809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brumbaugh K, et al. Overview of the generation, validation, and application of phosphosite-specific antibodies. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;717:3–43. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-024-9_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dopfer EP, et al. Analysis of novel phospho-ITAM specific antibodies in a S2 reconstitution system for TCR-CD3 signalling. Immunol Lett. 2010;130:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DiGiovanna MP, Stern DF. Activation state-specific monoclonal antibody detects tyrosine phosphorylated p185neu/erbB-2 in a subset of human breast tumors overexpressing this receptor. Cancer Res. 1995;55:1946–1955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nita-Lazar A, Saito-Benz H, White FM. Quantitative phosphoproteomics by mass spectrometry: past, present, and future. Proteomics. 2008;8:4433–4443. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marks JD, et al. By-passing immunization. Human antibodies from V-gene libraries displayed on phage. J Mol Biol. 1991;222:581–597. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90498-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCafferty J, Griffiths AD, Winter G, Chiswell DJ. Phage antibodies: filamentous phage displaying antibody variable domains. Nature. 1990;348:552–554. doi: 10.1038/348552a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang AS, Barbas CF, Janda KD, Benkovic SJ, Lerner RA. Linkage of recognition and replication functions by assembling combinatorial antibody Fab libraries along phage surfaces. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:4363–4366. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.10.4363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mersmann M, et al. Towards proteome scale antibody selections using phage display. N Biotechnol. 2010;27:118–128. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sidhu SS, et al. Phage-displayed antibody libraries of synthetic heavy chain complementarity determining regions. J Mol Biol. 2004;338:299–310. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feldhaus MJ, et al. Flow-cytometric isolation of human antibodies from a nonimmune Saccharomyces cerevisiae surface display library. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:163–170. doi: 10.1038/nbt785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanes J, Schaffitzel C, Knappik A, Pluckthun A. Picomolar affinity antibodies from a fully synthetic naive library selected and evolved by ribosome display. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:1287–1292. doi: 10.1038/82407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cobaugh CW, Almagro JC, Pogson M, Iverson B, Georgiou G. Synthetic antibody libraries focused towards peptide ligands. J Mol Biol. 2008;378:622–633. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shih HH, et al. An ultra-specific avian antibody to phosphorylated tau protein reveals a unique mechanism for phosphoepitope recognition. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:44425–44434. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.415935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vielemeyer O, et al. Direct selection of monoclonal phosphospecific antibodies without prior phosphoamino acid mapping. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:20791–20795. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.008730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaneko T, et al. Superbinder SH2 domains act as antagonists of cell signaling. Sci Signal. 2012;5:ra68. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pershad K, Wypisniak K, Kay BK. Directed evolution of the forkhead-associated domain to generate anti-phosphospecific reagents by phage display. J Mol Biol. 2012;424:88–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malabarba MG, et al. A repertoire library that allows the selection of synthetic SH2s with altered binding specificities. Oncogene. 2001;20:5186–5194. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clackson T, Wells JA. A hot spot of binding energy in a hormone-receptor interface. Science. 1995;267:383–386. doi: 10.1126/science.7529940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bogan AA, Thorn KS. Anatomy of hot spots in protein interfaces. J Mol Biol. 1998;280:1–9. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watson JD, Milner-White EJ. A novel main-chain anion-binding site in proteins: the nest. A particular combination of phi,psi values in successive residues gives rise to anion-binding sites that occur commonly and are found often at functionally important regions. J Mol Biol. 2002;315:171–182. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Landry RC, et al. Antibody recognition of a conformational epitope in a peptide antigen: Fv-peptide complex of an antibody fragment specific for the mutant EGF receptor, EGFRvIII. J Mol Biol. 2001;308:883–893. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hollingsworth SA, Karplus PA. A fresh look at the Ramachandran plot and the occurrence of standard structures in proteins. Biomol Concepts. 2010;1:271–283. doi: 10.1515/BMC.2010.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.North B, Lehmann A, Dunbrack RL., Jr A new clustering of antibody CDR loop conformations. J Mol Biol. 2011;406:228–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alving CR. Antibodies to liposomes, phospholipids and phosphate esters. Chem Phys Lipids. 1986;40:303–314. doi: 10.1016/0009-3084(86)90075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levine JS, Branch DW, Rauch J. The antiphospholipid syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:752–763. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra002974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yaffe MB, Smerdon SJ. PhosphoSerine/threonine binding domains: you can’t pSERious? Structure. 2001;9:R33–38. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00580-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaneko T, Joshi R, Feller SM, Li SS. Phosphotyrosine recognition domains: the typical, the atypical and the versatile. Cell Commun Signal. 2012;10:32. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-10-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seet BT, Dikic I, Zhou MM, Pawson T. Reading protein modifications with interaction domains. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:473–483. doi: 10.1038/nrm1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kunkel TA. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:488–492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.2.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bostrom J, et al. Variants of the antibody herceptin that interact with HER2 and VEGF at the antigen binding site. Science. 2009;323:1610–1614. doi: 10.1126/science.1165480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rondot S, Koch J, Breitling F, Dubel S. A helper phage to improve single-chain antibody presentation in phage display. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:75–78. doi: 10.1038/83567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomsen ND, Koerber JT, Wells JA. Structural snapshots reveal distinct mechanisms of procaspase-3 and -7 activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:8477–8482. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306759110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luft JR, DeTitta GT. A method to produce microseed stock for use in the crystallization of biological macromolecules. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1999;55:988–993. doi: 10.1107/s0907444999002085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holton J, Alber T. Automated protein crystal structure determination using ELVES. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:1537–1542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306241101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Method Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaufmann B, et al. Neutralization of West Nile virus by cross-linking of its surface proteins with Fab fragments of the human monoclonal antibody CR4354. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:18950–18955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011036107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen VB, et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baker NA, Sept D, Joseph S, Holst MJ, McCammon JA. Electrostatics of nanosystems: application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10037–10041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181342398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Winn MD, et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67:235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.