Abstract

Binding of natural killer (NK) cell inhibitory receptors to MHC-I confers increased responsiveness to NK cells by a process known as NK cell licensing/education. Reduced MHC-I expression or a lack of inhibitory receptors for MHC-I results in diminished NK cell responsiveness. In this study, we evaluated the effect of human and mouse NK cell licensing on early stages of natural cytotoxicity. Unlicensed NK cells did not form as many stable conjugates with target cells. The reduction of NK cell conjugation to target cells was not attributed to altered β2 integrin LFA-1 properties but was instead due to reduced inside-out signaling to LFA-1 by activating receptors. For those unlicensed NK cells that did form conjugates, LFA-1-dependent granule polarization was similar to that in licensed NK cells. Thus, licensing controls signals as proximal as inside-out signaling by activating receptors but not integrin outside-in signaling for granule polarization.

Introduction

Natural killer (NK) cells possess several sets of activating and stochastically expressed inhibitory receptors (IR), which control different steps in cytotoxic lymphocyte-mediated killing of target cells, including conjugation of NK cells to target cells, polarization of lytic granules towards target cells, and degranulation (1, 2). Prior engagement of NK cells with MHC class I molecules (MHC-I) by IRs allows for greater intrinsic responsiveness to subsequent activation stimuli through a process called NK cell licensing (aka education) (3–6). The number of IR engaged with MHC and the strength of MHC binding to IR calibrate the potential responsiveness of each NK cell for cytotoxicity and cytokine secretion (7, 8).

It is still not clear how licensing affects different steps in NK cell cytotoxicity, such as the contribution of the β2 integrin LFA-1, which is essential for tight conjugation with target cells (9) and for lytic granule polarization (10, 11). Binding of cytotoxic lymphocytes to the adhesion ligand ICAM-1 requires an open conformation of LFA-1, which is regulated by inside-out signals from other receptors (12). In this study, we evaluated whether unlicensed NK cells have a defect in inside-out signaling to LFA-1 for conjugate formation or in outside-in signaling by LFA-1 for lytic granule polarization.

Materials and Methods

Cells

Human NK cells were isolated by negative selection using the EasySep Human NK Cell Enrichment Kit (StemCell Technologies). Human NK cells used in this study were >95% CD56+, CD3−. Human blood samples from anonymized healthy donors were drawn for research purposes at the NIH Blood Bank under an NIH IRB approved protocol with informed consent. C57BL/6 and β2m−/− mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. Mouse NK cells were isolated from spleens by negative selection using NK Cell Isolation Kit I or II (Miltenyi Biotec) or EasySep Mouse NK Cell Enrichment Kit (StemCell Technologies). Mouse NK cells used in this study were >70% NKp46+, CD3−, CD19−. All animal experiments were approved by the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Animal Care and Use Committee.

Depletion of IR+ human NK cells

To isolate human NK cells that do not express inhibitory receptors KIR2DL1 (CD158a), KIR2DL2/3 (CD158b), KIR3DL1 (CD158e), and NKG2A (CD159a), NK cells were incubated with purified Abs for CD158a (1432111, R & D Systems) [3.9 µg/ml], CD158b (GL183, Beckman Coulter) [3.12 µ;g/ml], CD158e (Z27, Beckman Coulter) [1.56 µ;g/ml], and CD159a (Z199, Beckman Coulter) [1.56 µ;g/ml] for 10 min at 25°C. Samples were washed, and incubated with 6 µ;g/ml biotin-conjugated goat F(ab)’2 anti-mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 10 min at 25°C. Samples were mixed with anti-biotin microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec), passed through a LS column (Miltenyi Biotec), and cells that flowed through were collected. Less than 10% of the recovered NK cells expressed CD158a, CD158b, CD158e, or NKG2A. The Abs used for IR-depletion also depleted NK cells that expressed the activating receptors KIR2DS2 and KIR3DS1.

Cytotoxicity assays

Human or mouse NK cells were added to PKH67-labeled K562 or YAC-1 cells, respectively, at the indicated effector to target (E:T) ratios and incubated at 37°C. After 4 hours, samples were placed on ice and propidium iodide (PI) (Sigma-Aldrich) was added as a viability dye to each sample. To determine target cell viability, flow cytometry was performed on a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) with data analysis from FlowJo (version 9.3.3, Tree Star).

NK–target cell conjugation assays

K562 or YAC-1 cells labeled with DiD-lipophilic dye (Life Technologies) were co-cultured at a 1:1 ratio for 20 min at 37°C with human or mouse NK cells labeled with CellTracker Green (Life Technologies), respectively. Flow cytometry was performed to determine the number of double-positive events (NK–target conjugates).

Binding to ICAM-1–coated beads

Soluble mouse ICAM-1 (mICAM-1) tagged at the C-terminus of the extracellular domain with (His)6 was prepared as described (13), and biotinylated using EZ-Link-Sulfo-LC-biotin (Pierce) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Streptavidin-coated 5.5-µ;m beads (Bangs Laboratories) were labeled with 0.5 µ;g (for mouse studies) or 5 µ;g (for human studies) of biotinylated mICAM-1–(His)6. CellTracker Green labeled human NK cells were incubated with 10 µ;g/ml CD56 Ab (B159, BD Biosciences) or 10 µ;g/ml of each NKp46 (9E2/Nkp46, BD Biosciences) and anti-2B4 Abs (C1.7, Beckman Coulter). CellTracker Green labeled mouse NK cells were labeled with 10 µ;g/ml isotype control or 10 µ;g/ml of each CD2 Ab (RM2-5, eBioscience), NK1.1 Ab (PK136, BD Biosciences), and NKp46 Ab (29A1.4, BioLegend). To cross-link Ab-bound receptors and evaluate inside-out signaling, the cells were co-cultured for 20 min at 37°C with mICAM-1–coated beads at a ratio of 1:1 in the presence of 6 µ;g/ml goat F(ab’)2 anti-IgG (Jackson Immunoresearch). Flow cytometry was performed to determine binding of NK cells to beads.

Lytic granule polarization

Human NK cells or mouse NK cells were co-cultured with K562 cells or CellTracker Orange (Life Technologies) labeled YAC-1 cells, respectively, for 1 hour at 37°C. Procedures were similar to those described in (13) with the exception that lytic granules were stained with mouse LAMP-1 Ab (1D4B, BD Biosciences) instead of perforin in mouse NK cell studies. Image processing and cropping was performed using Adobe Photoshop CS4.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 software. Statistical comparisons between two groups were made by paired two-tailed Student’s T test for human NK cell studies and by unpaired two-tailed Student’s T test for mouse NK cell studies. P values < 0.05 were considered significant: n.s., non-significant; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

Results and Discussion

Isolation of Unlicensed NK cells

We investigated the early steps in natural cytotoxicity by unlicensed NK cells in two settings: 1) unlicensed NK cells from the MHC-I deficient environment of β2m−/− mice (3, 14, 15), and 2) unlicensed NK cells from human peripheral blood that lack inhibitory receptors KIR2DL1, KIR2DL2, KIR2DL3, KIR3DL1, and NKG2A (5, 16). NK cells from the spleens of β2m−/− mice express markers of mature NK cells yet are hyporesponsive (14, 15). For IR− human NK cells, a depletion strategy was employed to obtain an unmanipulated population of unlicensed human NK cells. After depletion of IR+ NK cells, the isolated population of NK cells included less than 10% of IR+ cells (Supplemental Fig. 1A). While the percentage of CD56+ cells did not change following depletion of IR+ NK cells, there was on average a 80% loss of CD56bright NK cells (Supplemental Fig. 1B), presumably due to NKG2A depletion (5). Expression of CD94 was reduced but not absent on IR− NK cells, as reported previously for NK cells devoid of NKG2A (5). The small subset of CD56bright NKG2A+ NK cells in peripheral blood are considered precursors of CD56dim KIR+ NK cells (17). Therefore, IR− NK cells represent a population that may be overall more mature than total peripheral blood NK cells. However, the maturation process of CD56dim NK cells includes an increase in the fraction of NK cells that express KIR (18). CD56dim NK cell maturation and licensing are thought of as uncoupled events, as natural cytotoxicity does not vary, independently of licensing, among stages of CD56dim NK cell maturation (19). As expected, total NK cells and enriched IR− NK cells had similar expression of NKp46, NKp30, NKR-P1A, CD16, NKG2C, NKG2D, 2B4, CD69, CD2, DNAM-1, ICAM-1, ILT-2, CD57, CD11a and CD18 (LFA-1), and total and IR− NK cells lacked expression of CD14 and CD19 (Supplemental Fig. 1C).

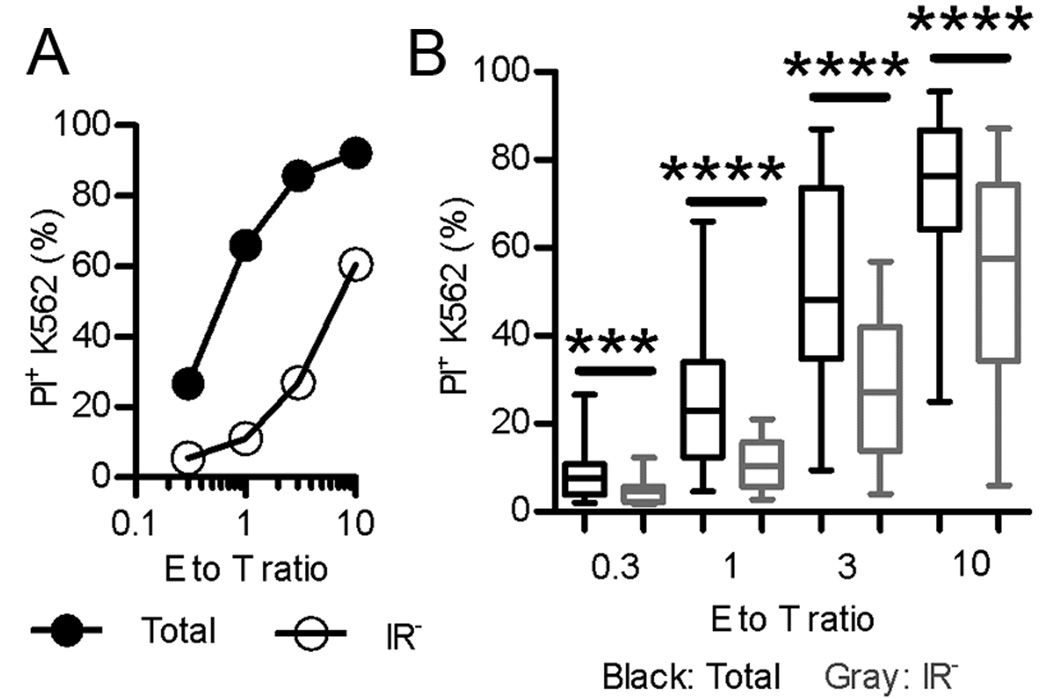

Reduced natural cytotoxicity with IR− human NK cells and β2m−/− mouse NK cells

K562 cells, an MHC-I deficient cell line, were killed more efficiently by total human NK cells than by IR− NK cells obtained by depletion of IR+ NK cells (Fig. 1A, B), consistent with the decreased responsiveness of unlicensed NK cells. Occasionally (approximately 1 in 8 donors), individual donors had NK cells that did not present much difference in cytotoxic activity between total and IR− NK cells (i.e., less than a 10% difference in killing of K562); NK cells from such donors typically showed poor cytotoxicity towards K562 (i.e., less than 50% killing at an E:T of 10). The low reactivity of NK cells from these donors may be due to a lack of priming or to poor licensing. For example, a high fraction of NK cells from these donors may have expressed KIR2DS1, which decreases NK cell licensing (20). As the purpose of this study was not to assign licensing potential to specific receptors, but to compare the properties of the bulk of unlicensed NK cells to those of the total NK cell population, the contribution of KIR2DS1 was not addressed here. Even with the inclusion of NK cells from all donors in our analysis, there was a statistically significant reduction (an average of ~50% reduction) in the killing of K562 cells by IR− NK cells relative to total NK cells (Fig. 1B). Additionally, in agreement with other studies (3, 21), β2m−/− mouse NK cells displayed decreased killing of YAC-1 cells relative to their wild-type C57BL/6 counterparts (Supplemental Fig. 2).

Figure 1. Reduced natural cytotoxicity by purified IR− NK cells.

(A) PI+ K562 cells following co-culture with total or IR− NK cells. Representative of over 20 experiments. (B) Box-and-Whisker plot indicating PI+ K562 cells following co-culture with total and IR− NK cells isolated from 24 individual donors. Plot indicates the minimal and maximal values, 25th and 75th percentiles, and the mean from n=24. K562 cells alone ≤ 5% PI+. ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

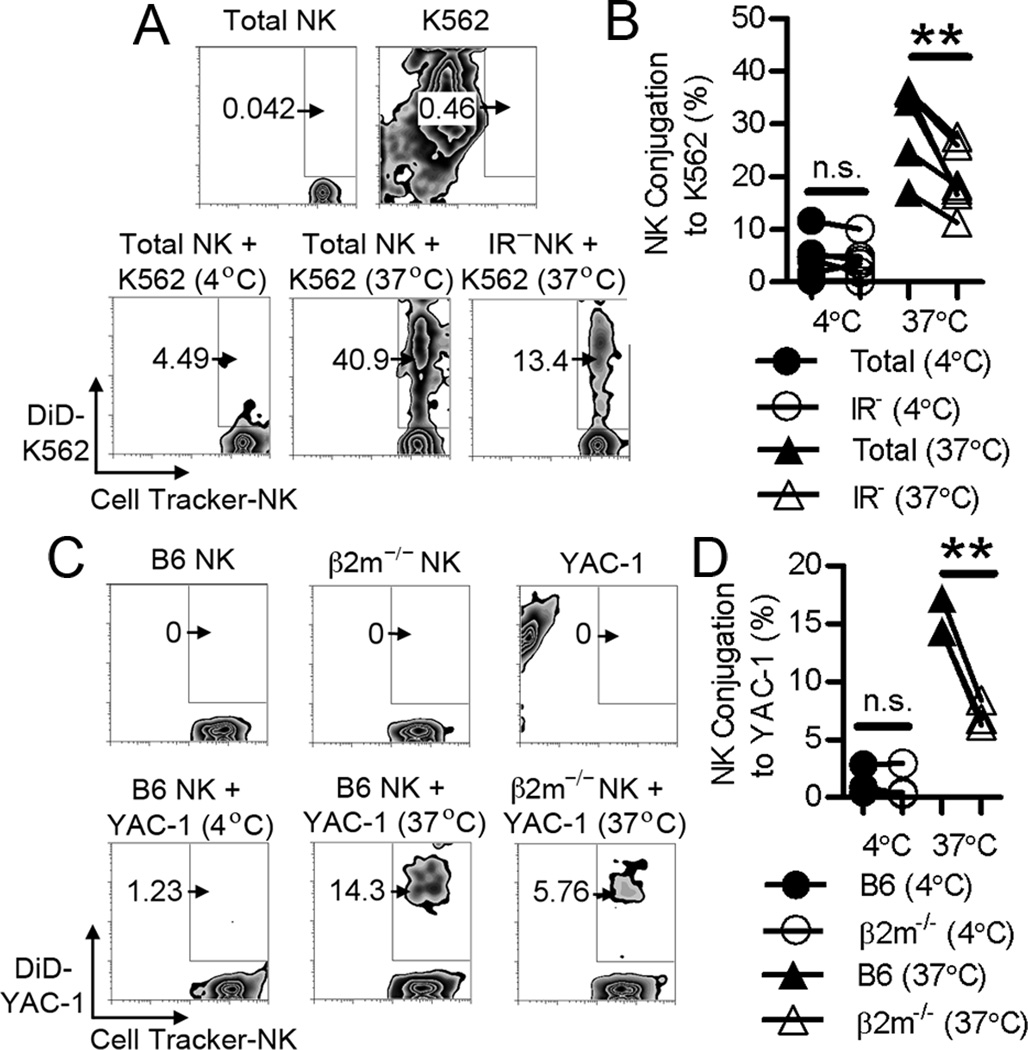

Unlicensed NK cells form fewer stable conjugates with target cells due to reduced inside-out signaling to LFA-1

Total and IR− human NK cells were evaluated for their ability to form tight conjugates with K562 cells. IR− NK cells displayed a ~33% reduction in conjugation to K562 cells relative to conjugation by total NK cells (Fig. 2A, B). In agreement, β2m−/− mouse NK cells displayed a ~50% reduction in conjugation to YAC-1 cells relative to conjugation by C57BL/6 NK cells (Fig. 2C, D).

Figure 2. Unlicensed NK cells are deficient in forming conjugates with target cells.

(A) Contour plots show the percentage of collected events within the double-positive gate in co-cultured DiD-labeled K562 cells and CellTracker Green-labeled human NK cells. Co-culture plots (bottom panel) were first gated on CellTracker Green+ cells. Representative of 6 experiments. (B) Human total or IR− NK cells in NK–K562 cell conjugates from individual experiments. n=6; **, P < 0.01; n.s., not significant. (C) Contour plots show the percentage of collected events within the double-positive gate in co-cultured DiD-labeled YAC-1 cells and CellTracker Green-labeled mouse NK cells. Co-culture plots (bottom panel) were first gated on CellTracker Green+ cells. Representative of 3 experiments. (D) C57BL/6 or β2m−/− NK cells in NK–YAC-1 cell conjugates from individual experiments. n=3; **, P < 0.01; n.s., not significant. Lines connect results within individual experiments.

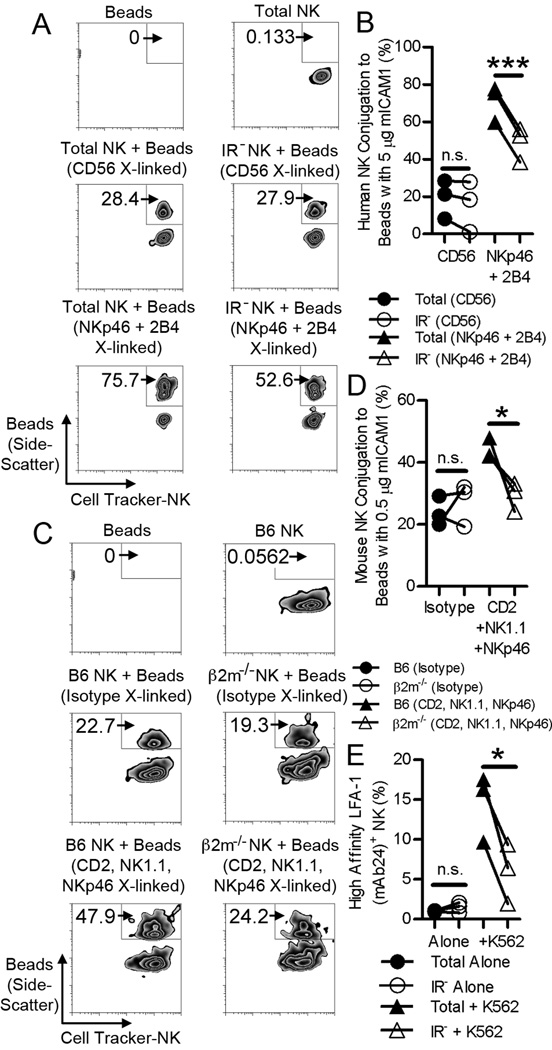

LFA-1 binding to ICAM-1, which is sufficient for adhesion by NK cells, can be enhanced by inside-out signals from NK cell activating receptors (22, 23). Therefore, the reduced conjugation to target cells exhibited by IR− NK cells may be due to impaired LFA-1 function or, indirectly, to reduced inside-out signals to LFA-1 by activating receptors. To test inside-out signaling, total and IR− NK cells were incubated with CD56 Ab (as negative control) or with the combination of Abs to NKp46 and 2B4. C57BL/6 and β2m−/− mouse NK cells were incubated with isotype control Abs or with the combination of Abs to CD2, NK1.1, and NKp46. Ab-coated NK cells were then incubated with beads coated with mICAM-1 in the presence of crosslinking F(ab’)2 anti-IgG to trigger receptor activation. Cross-linking of negative control Abs did not result in any significant difference in NK cell binding to mICAM-1-coated beads between licensed and unlicensed NK cells (Fig. 3B, D). Therefore, NK cell licensing does not alter the intrinsic ability of LFA-1 to bind to mICAM-1. In contrast, cross-linking of co-activating receptors resulted in enhanced binding to mICAM-1-coated beads for both human and mouse licensed and unlicensed NK cells (Fig. 3 A, B, C, D). Notably, co-activating receptor cross-linking resulted in significantly greater conjugation of licensed NK cells to mICAM-1–coated beads than co-activating receptor cross-linking of unlicensed NK cells (Fig. 3B, D). This result implies that licensing has a direct impact on signaling by the activating receptors examined. Furthermore, incubation of NK cells with K562 resulted in greater increase in the expression of high-affinity LFA-1 within total human NK cells compared to IR− NK cells, as assessed using the mAb 24 specific for an open conformation of LFA-1 (Fig. 3E). Therefore, we conclude that unlicensed NK cells demonstrate diminished inside-outside signaling to LFA-1 by activating receptors, which, in turn, results in decreased adhesion to target cells.

Figure 3. Licensing does not impact NK cell binding to ICAM-1 but inside-out signaling by activating receptors.

(A) Contour plots show the percentage of collected events within the double-positive gate in co-cultures of CellTracker Green-labeled human NK cells with mICAM-1-coated beads. Plots of total and IR− human NK cells conjugated with mICAM-1-coated beads in the presence of CD56 or NKp46 and 2B4 Ab-mediated cross-linking (middle and bottom panels) were first gated on CellTracker Green+ cells. Representative of n=3. (B) Total and IR− NK cells conjugated to mICAM-1-coated beads after cross-linking of Abs to CD56 or NKp46 and 2B4. n=3; ***, P < 0.001; n.s., not significant. (C) Contour plots show the percentage of collected events within the double-positive gate in co-cultures of CellTracker Green-labeled mouse NK cells with mICAM-1–coated beads. Plots of C57BL/6 and β2m−/− mouse NK cells conjugated with mICAM-1-coated beads after cross-linking of isotype control or Abs to CD2, NK1.1 and NKp46 (middle and bottom panels) were first gated on CellTracker Green+ cells. Representative of n=3. (D) C57BL/6 and β2m−/− NK cells conjugated to mICAM-1-coated beads after cross-linking of isotype control or Abs to CD2, NK1.1 and NKp46. n=3; *, P < 0.05; n.s., not significant. (E) Total and IR− human NK cells that express an open conformation of LFA-1 (detected by mAb 24) either alone or after a 1:1 co-culture with K562 for 20 min. n=3; *, P < 0.05; n.s., not significant. Lines connect results across samples from the same donor.

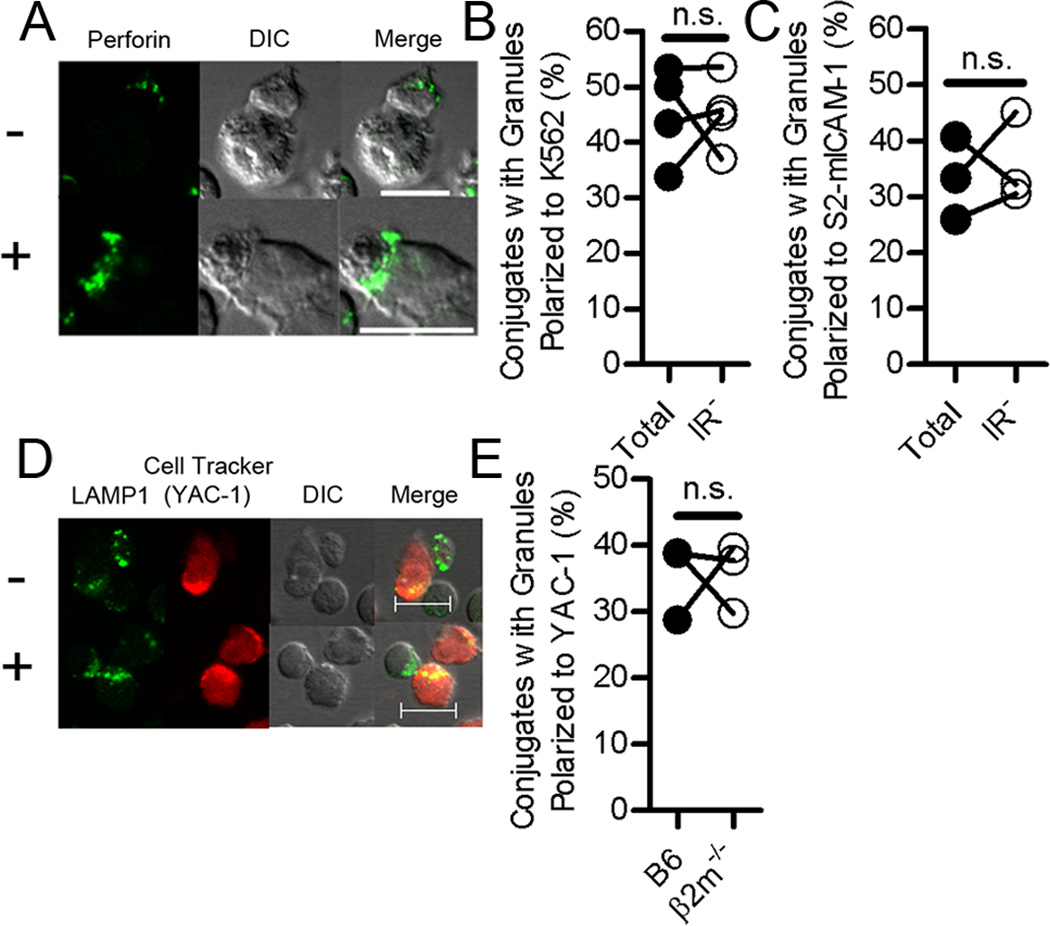

LFA-1 signaling for lytic granule polarization occurs normally in unlicensed NK cells

We then tested whether outside-in signaling by LFA-1 is also subject to modulation through licensing. LFA-1 signaling in human NK cells is sufficient to promote lytic granule polarization, independently of inside-out signals (10, 11). This property of LFA-1 is unique to NK cells, as LFA-1 in T cells does not signal in the absence of inside-out signals (1, 12). To test the impact of NK cell licensing on signals for lytic granule polarization, we compared total and IR− human NK cells for their ability to polarize granules towards ICAM-1 expressing target cells, including K562 and insect S2 cells that express mICAM-1 (S2-mICAM-1 cells) (13). A similar fraction of total and IR− human NK cells displayed granule polarization towards K562 cells (Fig. 4A, B) or S2-mICAM-1 cells (Fig. 4C). Similar to human NK cells co-cultured with K562, unlicensed β2m−/− mouse NK cells polarized their lytic granules towards YAC-1 cells as frequently as total C57BL/6 NK cells (Fig. 4D, E). Thus, among NK cells that had formed contacts with target cells, granule polarization towards target cells occurred regardless of their licensed status. We cannot exclude that NK cell licensing may influence some aspect of lytic granule polarization. However, it is clear that licensing controls inside-out signals to LFA-1 for greater adhesion more so than the ability of LFA-1 to signal for granule polarization at sites of NK–target cell contacts.

Figure 4. Lytic granule polarization toward target cells is not impaired in human IR− NK cells or NK cells from β2m−/− mice.

(A) Confocal image sections of human NK cells conjugated with K562 illustrating examples of unpolarized (−) or polarized (+) lytic granules. (B, C) Frequency of total NK and IR− NK cells that displayed granule polarization among the NK–K562 cell conjugates scored (B) or among the NK–S2-mICAM-1 cell conjugates scored (C) from three or four individual experiments. n.s., not significant. (D) Confocal image sections showing examples of mouse NK cells conjugated with YAC-1 cells with unpolarized (−) or polarized (+) lytic granules (YAC-1 cells are marked with CellTracker Orange). (E) Frequency of C57BL/6 (B6) and β2m−/− mouse NK cells that displayed granule polarization among the NK–YAC-1 cell conjugates scored from three individual experiments. n.s., not significant. Lines connect results within individual experiments. Scale bars = 10 µ;m. Fifty to 200 NK–target cell conjugates were scored for granule polarization toward target cells per experiment.

Conclusions

In this study, we found that NK cell licensing increases the strength of NK cell adhesion to target cells. Licensing did not, however, affect the ability of LFA-1 to bind to ICAM-1 in the absence of other receptor–ligand interactions, indicating that licensing does not influence the initial contact of NK cells with target cells. The enhanced stable adhesion of NK cells to target cells promoted by licensing is due to stronger inside-out signaling by activating receptors that bind to ligands on target cells. NK cell licensing did not have a measurable impact on outside-in signaling by LFA-1 for lytic granule polarization in those NK cells that had established contact with target cells. We conclude that licensing controls LFA-1-dependent adhesion indirectly, as it acts by promoting stronger signaling by other activating receptors, including inside-out signals to LFA-1, rather than the intrinsic ability of LFA-1 to signal. Our study establishes boundaries to NK cell functions that may be controlled by licensing, which could help define how NK cell licensing by inhibitory receptors promotes the function of activating receptors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program at the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (L.M.T., M.E.P. and E.O.L.).

Abbreviations used in this article

- β2m

beta-2-microglobulin

- IR

inhibitory receptor

- KIR

killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor

- LAMP-1

lysosomal-associated membrane glycoprotein 1

- mICAM-1

mouse ICAM-1

- PI

propidium iodide

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Long EO, Sik Kim H, Liu D, Peterson ME, Rajagopalan S. Controlling natural killer cell responses: integration of signals for activation and inhibition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2013;31:227–258. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orange JS. Formation and function of the lytic NK-cell immunological synapse. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:713–725. doi: 10.1038/nri2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim S, Poursine-Laurent J, Truscott SM, Lybarger L, Song YJ, Yang L, French AR, Sunwoo JB, Lemieux S, Hansen TH, Yokoyama WM. Licensing of natural killer cells by host major histocompatibility complex class I molecules. Nature. 2005;436:709–713. doi: 10.1038/nature03847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoglund P, Brodin P. Current perspectives of natural killer cell education by MHC class I molecules. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:724–734. doi: 10.1038/nri2835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anfossi N, Andre P, Guia S, Falk CS, Roetynck S, Stewart CA, Breso V, Frassati C, Reviron D, Middleton D, Romagne F, Ugolini S, Vivier E. Human NK cell education by inhibitory receptors for MHC class I. Immunity. 2006;25:331–342. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elliott J, Yokoyama W. Unifying concepts of MHC-dependent natural killer cell education. Trends Immunol. 2011;32:364–372. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joncker NT, Fernandez NC, Treiner E, Vivier E, Raulet DH. NK Cell Responsiveness Is Tuned Commensurate with the Number of Inhibitory Receptors for Self-MHC Class I: The Rheostat Model. Journal of Immunology. 2009;182:4572–4580. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brodin P, Lakshmikanth T, Johansson S, Karre K, Hoglund P. The strength of inhibitory input during education quantitatively tunes the functional responsiveness of individual natural killer cells. Blood. 2009;113:2434–2441. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-156836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmidt RE, Bartley G, Levine H, Schlossman SF, Ritz J. Functional characterization of LFA-1 antigens in the interaction of human NK clones and target cells. J Immunol. 1985;135:1020–1025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barber DF, Faure M, Long EO. LFA-1 contributes an early signal for NK cell cytotoxicity. J Immunol. 2004;173:3653–3659. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.3653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bryceson YT, March ME, Barber DF, Ljunggren HG, Long EO. Cytolytic granule polarization and degranulation controlled by different receptors in resting NK cells. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1001–1012. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luo BH, Carman CV, Springer TA. Structural basis of integrin regulation and signaling. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:619–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.March ME, Long EO. beta2 integrin induces TCRzeta-Syk-phospholipase C-gamma phosphorylation and paxillin-dependent granule polarization in human NK cells. J Immunol. 2011;186:2998–3005. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elliott JM, Wahle JA, Yokoyama WM. MHC class I-deficient natural killer cells acquire a licensed phenotype after transfer into an MHC class I-sufficient environment. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2010;207:2073–2079. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joncker NT, Shifrin N, Delebecque F, Raulet DH. Mature natural killer cells reset their responsiveness when exposed to an altered MHC environment. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2010;207:2065–2072. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yawata M, Yawata N, Draghi M, Partheniou F, Little AM, Parham P. MHC class I-specific inhibitory receptors and their ligands structure diverse human NK-cell repertoires toward a balance of missing self-response. Blood. 2008;112:2369–2380. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-143727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freud AG, Caligiuri MA. Human natural killer cell development. Immunol Rev. 2006;214:56–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooley S, Xiao F, Pitt M, Gleason M, McCullar V, Bergemann TL, McQueen KL, Guethlein LA, Parham P, Miller JS. A subpopulation of human peripheral blood NK cells that lacks inhibitory receptors for self-MHC is developmentally immature. Blood. 2007;110:578–586. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-036228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bjorkstrom NK, Riese P, Heuts F, Andersson S, Fauriat C, Ivarsson MA, Bjorklund AT, Flodstrom-Tullberg M, Michaelsson J, Rottenberg ME, Guzman CA, Ljunggren HG, Malmberg KJ. Expression patterns of NKG2A, KIR, and CD57 define a process of CD56dim NK-cell differentiation uncoupled from NK-cell education. Blood. 2010;116:3853–3864. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-281675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fauriat C, Ivarsson MA, Ljunggren HG, Malmberg KJ, Michaelsson J. Education of human natural killer cells by activating killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors. Blood. 2010;115:1166–1174. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-245746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bix M, Liao NS, Zijlstra M, Loring J, Jaenisch R, Raulet D. Rejection of class I MHC-deficient haemopoietic cells by irradiated MHC-matched mice. Nature. 1991;349:329–331. doi: 10.1038/349329a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barber DF, Long EO. Coexpression of CD58 or CD48 with intercellular adhesion molecule 1 on target cells enhances adhesion of resting NK cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:294–299. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.1.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bryceson YT, Ljunggren HG, Long EO. Minimal requirement for induction of natural cytotoxicity and intersection of activation signals by inhibitory receptors. Blood. 2009;114:2657–2666. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-201632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.