Abstract

Recently, crystal structures of key complexes in antigen presentation have been reported. HLA-DM functions in antigen presentation by catalyzing dissociation of an invariant chain remnant from the peptide binding groove and stabilizing empty MHC class II proteins in a peptide-receptive conformation. The crystal structure of a MHC class II – HLA-DM complex explains how HLA-DM stabilizes an otherwise short-lived transition state and promotes a rapid peptide exchange process which favors the highest-affinity ligands. HLA-DO has sequence similarity with MHC class II molecules yet inhibits antigen presentation. The structure of the HLA-DO – HLA-DM complex shows that it blocks HLA-DM activity as a substrate mimic. Alterations in the efficiency of DM-mediated peptide selection may contribute to autoimmune pathologies, which will be an exciting area for future investigation.

Keywords: antigen presentation, MHC class II molecules

The MHC class II pathway

When an infectious agent enters the body at a localized anatomical site, the small number of naïve T cells available for a particular pathogen-derived peptide (approximately 20-200 CD4 T cells in mice) need to locate the relevant antigen presenting cells (APCs) [1]. This search operation requires that relevant peptides are displayed for sufficient periods of time on the surface of APCs for interaction with naïve T cells. MHC class II (MHCII) molecules have evolved to present peptides for extended periods of time, with a half-life of days to weeks. Such half-lives are highly unusual in biological systems, which are typically in the range of seconds to minutes. High-affinity binding is conferred by two complementary sets of interactions between MHCII molecules and peptides: a set of conserved hydrogen bonds between the peptide backbone and the helices of a MHCII molecule, as well as binding of peptide side chains in pockets of the groove [2, 3]. Peptides that bind with a long half-life to the respective MHCII molecule tend to dominate the T cell response (immunodominance). Key concepts of MHC class II antigen presentation are introduced in Textbox 1.

Textbox.

Key concepts in antigen presentation

| HLA-DM | A membrane protein with an overall organization like MHCII proteins, but without a groove that could accommodate peptides. DM is targeted to the MHCII peptide loading compartment where it facilitates dissociation of the invariant chain remnant referred to as CLIP. DM also stabilizes empty MHCII proteins and promotes selection of high-affinity peptides (editing). |

| HLA-DO | An inhibitor of MHCII antigen presentation. DO binds with high affinity to DM and blocks the active surface of DM. Expression of DO is down-regulated when dendritic cells mature and B cells become activated and move into germinal centers. These mechanisms are consistent with the concept that DO helps to reduce autoimmunity by inhibition of self-antigen presentation by MHCII proteins at steady-state. |

| Immunodominance | Responses to complex antigens tend to be dominated by T cells specific for one or a few epitopes located on the protein; these epitopes are considered to be immunodominant. Parameters that affect immunodominance include protein abundance, antigen processing, peptide affinity as well as the T cell repertoire. Selection of the peptide repertoire by DM is a key determinant of immunodominance. |

| Catalysis | DM is considered to act like an enzyme because it greatly accelerates the rate of a reaction, in this case peptide binding to MHCII proteins. This formalism can be applied to the structural studies described here: DM (the enzyme) binds to a MHCII molecule with a partially empty groove (transition state) and stabilizes this state. Peptides dissociate from and bind to this transition state with rapid kinetics. |

| Editing | DM accelerates dissociation of all MHCII-bound peptides, acting preferentially on MHCII proteins with bound low-affinity peptides. The structure of the DR1 – DM complex identifies the mechanism of rapid peptide exchange: part of the groove is initially inaccessible to incoming peptides. Thus, a high-affinity groove is converted to a low-affinity binding site. High-affinity peptides fully occupy the groove and terminate the editing process by inducing DM dissociation. |

| Peptide repertoire | Hundreds to thousands of different peptides are bound by MHCII proteins, with many peptides originating from self-antigens. The vast majority of peptides generated in the MHCII loading compartment are low-affinity binders. In the absence of DM, presentation of immunodominant peptides is greatly reduced, likely due to competition by abundant lower-affinity peptides. |

Both high and low-affinity peptides bind with similar on-rates to MHCII molecules, and even low-affinity peptides can bind for several hours. This raises a critical question: how are the highest-affinity binders selected for within a much larger pool of lower affinity binders? This selection function is executed by DM (HLA-DM in humans, H2-DM in mice), a chaperone that greatly accelerates peptide exchange [3-5]. The impact of DM on peptide binding kinetics to MHCII is illustrated by the influenza hemagglutinin (HA) peptide (306-318), which binds with a half-life of ~1 month to HLA-DR1 (DR1). The half-life of this peptide is reduced to 2 minutes when it is bound to a HLA-DR1 – HLA-DM complex [6]. In this review, we will discuss recent biochemical and structural advances that have provided a molecular explanation for the ability of DM to accelerate peptide exchange and promote selection of high-affinity ligands. We will also discuss the molecular mechanism responsible for inhibition of DM activity by HLA-DO (DO).

DM-mediated peptide repertoire selection

DM was discovered by characterization of mutant EBV transformed B cells lines with a severe but incomplete defect in antigen presentation by multiple human MHCII molecules (HLA-DR, HLA-DQ and HLA-DP) [7]. MHCII molecules have a strong tendency to aggregate when the binding groove is not occupied by peptides. They assemble in the ER with the invariant chain, which protects the binding groove until MHCII-invariant chain complexes reach the late endosomal peptide loading compartment. Here, the invariant chain is degraded, leaving invariant chain remnants known as class II associated invariant chain peptides (CLIP) in the groove. DM induces CLIP dissociation, rendering the groove accessible to peptides generated by proteolysis from microbial antigens [3, 5]. CLIP has a wide range of affinities for different allelic products of MHCII genes. For MHCII proteins with a high affinity for CLIP, DM ensures efficient antigen presentation. However, DM is not universally required for CLIP dissociation because certain MHCII proteins have a low affinity for CLIP. In the absence of DM, a significant antigen presentation defect is nevertheless observed because DM stabilizes empty MHCII proteins following dissociation of CLIP or other peptides [5, 8]. This chaperone function is, in fact, a central element of DM function [3, 9].

Lastly, DM has a profound effect on the peptide repertoire presented by MHCII proteins to CD4 T cells. DM can induce dissociation of any peptide from MHCII proteins, and the resulting selection process (also referred to as ‘editing’) favors the highest-affinity peptides [10, 11]. Peptide exchange is also facilitated by the low pH environment of the peptide loading compartment, while it is slowed considerably by the neutral pH at the cell surface. This editing mechanism is a critical element of immunodominance. Quantification of peptides from hen egg lysozyme bound to I-Ak showed that presentation of the immunodominant 48-63 peptide was reduced 1,145-fold in the absence of DM, while presentation of two subdominant epitopes was reduced to a lesser extent (60 and 12 fold) [12]. High-affinity peptides may be out-competed by low-affinity peptides in the absence of DM.

DM binds a short-lived MHCII conformer

Much effort has been devoted to determine the molecular mechanism for the three functional properties of DM described above: destabilization of all MHCII-peptide complexes including those formed with CLIP, stabilization of an ‘empty’ MHCII groove and editing of the peptide repertoire. DM has a similar domain organization as MHCII proteins, but lacks the ability to bind peptides [5]. Extensive mutagenesis experiments on HLA-DR (DR, a human MHCII protein) and DM identified large lateral surfaces through which these proteins interact, consistent with the fact that they are tethered to the same endosomal membranes [6, 13]. Furthermore, several mutations that greatly impair sensitivity to the action of DM are located on the DRα chain in the vicinity of the peptide N-terminus [13, 14].

Direct binding studies between DM and DR molecules using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) showed that the interaction is determined by the occupancy state of the peptide binding groove: low-affinity DR-peptide complexes bind to DM with substantially faster kinetics than high-affinity complexes [14]. Interestingly, covalent linkage of the peptide (either in the groove or to the N-terminus of the DRβ chain) results in a complete loss of DM binding (due to greatly increased peptide affinity). This result provided an important clue to the mechanism: stepwise truncation of such a covalently linked peptide revealed that DM binding only occurs when several N-terminal peptide residues are missing, including the anchor for the hydrophobic P1 pocket. DM thus only binds to DR molecules with an empty P1 pocket and does not destabilize DR-peptide complexes with a fully occupied groove [14]. These results are consistent with the proposal that DM acts like an enzyme that binds to a short-lived transition state [15]. Furthermore, these results are supported by the poor DM sensitivity observed for a DR1 mutant in which the P1 pocket is filled (DRβ G86Y mutation) [16].

These binding studies also showed that DM forms stable, long-lived complexes with DR molecules following peptide dissociation at low pH. However, addition of peptide resulted in dissociation of the DR-DM complex [14]. This means that DM induces CLIP dissociation from MHCII proteins and then forms a stable complex with empty MHCII proteins until a suitable peptide is available. This is consistent with the finding that DR-DM complexes isolated from cells are largely devoid of peptide [3, 9].

Crystal structure of the DR1-DM complex

These functional studies enabled crystallization of this important complex [17]. An N-terminally truncated peptide was covalently linked to the DR1 molecule, through a disulfide bond in the P6 pocket. Furthermore, the β chains of DM and DR1 were linked using sortase A to mimic membrane tethering of DM and DR (which enhances the interaction between the two molecules) [17, 18].

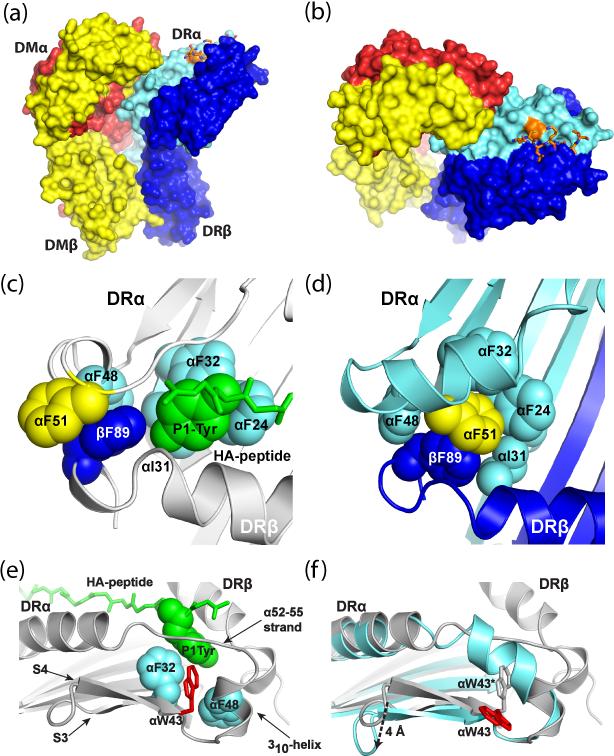

The structure shows that the interaction is dominated by the DRα and DMα chains (Figure 1), and there is also a smaller contact surface between the β2 domains of DR and DM [17]. As predicted, DM interacts with the DRα1 domain close to the peptide N-terminus. A large fraction of the binding groove is devoid of peptide, and there is little electron density for residues P2, P3 and P4 of the linked peptide as these residues are presumably in rapid motion.

Figure 1. Structure of the complex between HLA-DR1 and HLA-DM.

a, DR1 and DM ectodomains are aligned parallel to each other. DRα and β chains are colored cyan and blue, respectively, DMα and β chains in red and yellow. b, Top view of the DR1-DM complex, showing that large part of the groove lacks a stably bound peptide. The peptide and its covalent attachment site on the DRα chain (DRα V65C) are colored orange. Both DMα1 (red) and β1 (yellow) domains interact with DRα1. c, Arrangement of key DR1 residues when the groove is occupied by a high-affinity peptide (influenza HA 306-318). The P1 tyrosine (Tyr) residue of the peptide occupies the hydrophobic P1 pocket. DRα F51 points out of the groove. d, Rearrangement of a key part of the groove in the DR1-DM complex. DRα F51 has moved into the hydrophobic P1 pocket, where it is stabilized by DRβ F89. e, f, Flipping of a critical tryptophan (DRα W43) is required for DM binding. In the DR1/HA peptide structure (e), DRα W43 interacts with the P1 tyrosine (Tyr) residue of the peptide and neighboring aromatic residues (DRα F32 and F48). In the DR1-DM complex, this tryptophan has rotated away from the P1 pocket (f). Conformational changes in the DRα 46-55 segment and the S3/S4 strand of the floor of the groove are highlighted in (f) through overlay of the DRα chains from the DR1-HA (grey) and DR1-DM (cyan) structures.

The structure reveals a major rearrangement of the peptide binding groove surrounding the P1 pocket. In the structure of DR1 with bound influenza HA peptide (res. 306-318) [2], residue DRα F51 is pointing out of the groove. However, in the DR1-DM complex, this hydrophobic residue is now located in the P1 pocket of the binding groove, at the position normally occupied by the P1 peptide side chain. This movement (~13 Å) is caused by a conformational change in the DRα 46-55 segment: in the DR1-HA structure, DRα 52-55 is an extended strand which forms critical hydrogen bonds to the peptide. In the DR1-DM structure, the entire DRα 46-55 segment becomes helical, repositioning DRα F51 into the P1 pocket.

These conformational changes are made possible by flipping of a critical tryptophan residue, DRα W43, away from the P1 pocket. In the DR1-HA structure this tryptophan interacts with the P1 anchor residue (tyrosine) as well as other neighboring aromatic amino acids. In the DR1-DM complex DRα W43 is instead rotated away from the P1 pocket and forms an essential interaction with DM. Dissociation of the peptide N-terminus and flipping of this tryptophan are likely to be closely linked events that enable DM binding. Both DRα W43 and its interaction partner on DM (DMα N125) are entirely conserved among DR/DM homologs in all examined species [17]. These rearrangements of the groove also position DRα E55 into the groove, where it interacts with DRβ N82 through a water-mediated hydrogen bond. In the DR1-HA structure this residue forms critical bidentate hydrogen bonds to the peptide backbone: mutation to alanine accelerates peptide dissociation ~3,000-fold [19].

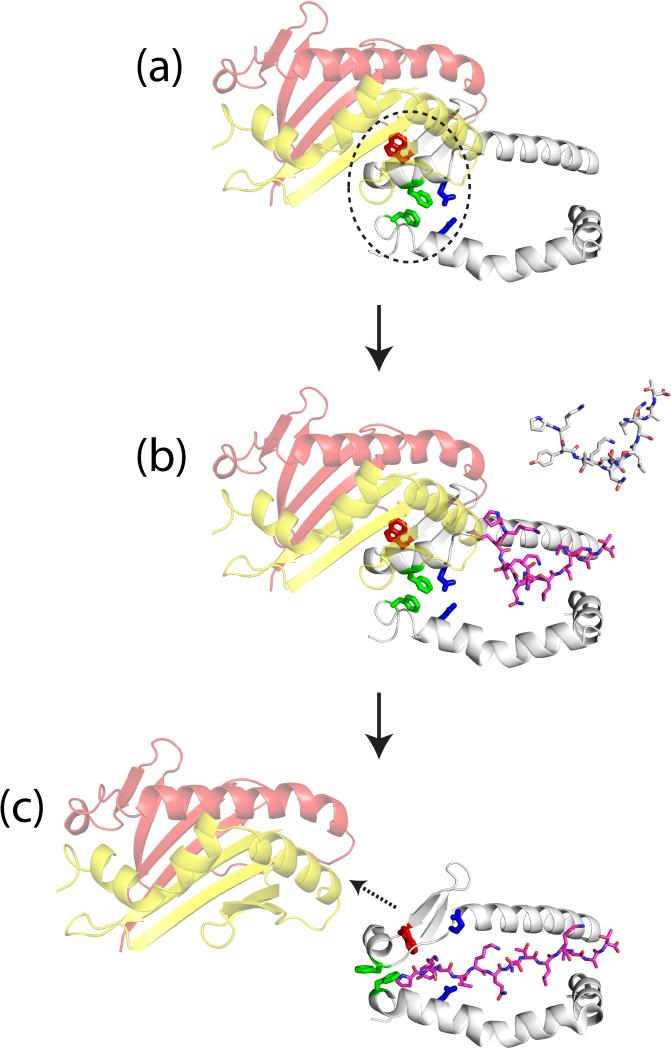

This means that DM induces peptide dissociation by preventing rebinding of a partially dissociated peptide (Figure 2). The same DR residues that prevent rebinding of the peptide N-terminus also stabilize the empty P1 pocket and render part of the groove initially inaccessible to incoming peptides. Initial binding of peptide to DR1-DM complexes is likely characterized by low-affinity interactions and rapid peptide exchange. Peptides are stably bound only when they effectively compete with DR residues for access to the P2 site (DRβ N82) and the P1 pocket. In this manner peptides are tested for strong binding to all parts of the groove. Such high-affinity binding by the peptide reverses the conformational changes required for the DR-DM interaction and induces DM dissociation [14]. This mechanism creates a rapid and efficient peptide exchange process, enabling DM to promote presentation of peptides with a half-life of >50 hours, while disfavoring peptides with a half-life of less than 10 hours [10].

Figure 2. Model for DM-catalyzed peptide exchange.

a, Stabilization of empty DR1 by DM. DRα F51 and DRβ F89 (green) move into the empty P1 pocket of DR1 following dissociation of the peptide N-terminus and stabilize this highly hydrophobic site. The rearrangements of the groove direct further stabilization mediated by DRα E55 and DRβ N82 (blue). b, Rapid selection of high-affinity peptides by DR1-DM complex. Only part of the groove is initially available to peptides, resulting in a rapid peptide exchange process that favors high-affinity ligands. c, Peptide-induced DM dissociation. Peptides that occupy the entire groove reverse conformational changes required for DM binding, terminating the peptide selection process.

Inhibition of DM by DO

HLA-DO (H-2O in mice) has a similar structural organization as classical MHCII molecules and more sequence similarity to MHCII proteins (~60%) than DM (~28%). The assembly of DO heterodimers is inefficient in the absence of DM, and DM is needed for egress from the ER. DO forms long-lived complexes with DM and inhibits the catalytic activity of DM [20]. Its expression is specifically down-regulated in germinal center B cells relative to naïve B cells, enhancing MHCII antigen presentation by germinal center B cells [21]. The major mechanism for shifting the balance between free DM and DM-DO complexes is transcriptional. Immunoelectron microscopy has shown that DO is present in the limiting membrane but not internal vesicles of multivesicular bodies, while DM is present in internal vesicles [20, 22]. It is thought that DO promotes immunological tolerance by reducing steady-state MHCII presentation by naïve B cells and immature dendritic cells [23]. Consistent with this idea, a recent study showed that H2-O (murine DO) deficient C57BL/6 mice developed high-titer anti-nuclear autoantibodies specific for dsDNA, ssDNA and histones [24]. Bone marrow chimera experiments showed that this phenotype also resulted when wild-type mice were reconstituted with H2-O−/− bone marrow. However, no proteinuria or histological evidence of kidney disease was observed, consistent with a multi-step model of autoimmune pathogenesis.

Why does DO fail to bind peptides?

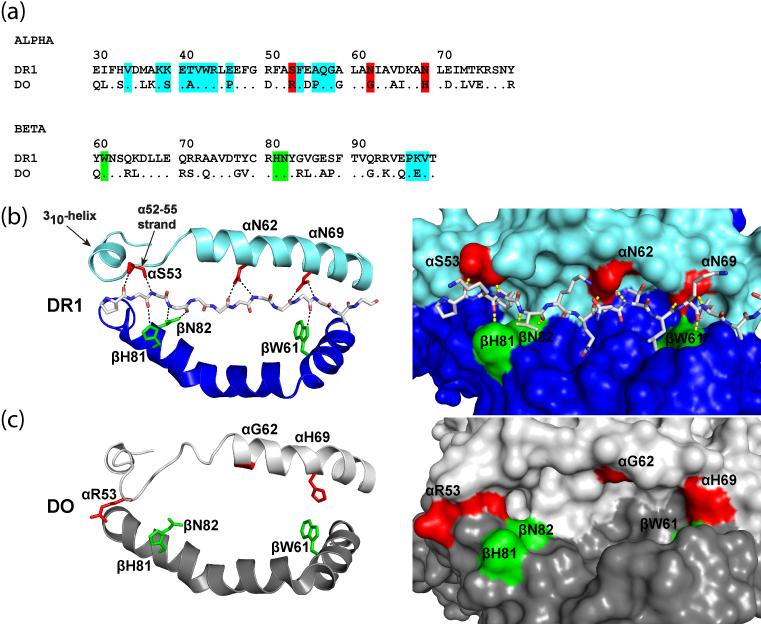

The recent crystal structure of the DO-DM complex showed that DO is indeed a MHCII homolog and inhibits DM function by acting as a substrate mimic [25, 26]. The overall topology of DO was found to be similar to that of classical MHCII proteins. Despite this similarity, the groove flanked by the DOα and β helices is empty in the structure of the DM-DO complex. Why does DO apparently not bind peptide, despite structural similarity to MHCII molecules? As mentioned above, peptide binding by all MHCII proteins requires formation of a set of conserved hydrogen bonds between the MHCII helices and the peptide backbone (Figure 3) [2]. Due to localized amino acid changes at DOα chain positions 53, 62 and 69, such hydrogen bonds could not be formed between the DOα chain and a peptide. Each of these amino acid differences results in loss of two conserved hydrogen bonds; six of 10 hydrogen bonding interactions observed in MHCII-peptide complexes can thus not be made by DO. Furthermore, access to the P9 pocket is blocked by DOα H69 which forms hydrogen bonds with DOβ D57 and Y37. The groove is further shortened at the other end by interaction of DOα R53 with the DOβ helix. It remains possible that DO forms short-lived interactions with peptides, but such interactions would likely to be of little biological relevance.

Figure 3. Structural basis for lack of peptide binding by HLA-DO.

a, Alignment of the α1 and β1 domain sequences of DR1 and DO. DM interface residues are highlighted in cyan. Five conserved MHCII residues form hydrogen bonds with the peptide backbone; those also conserved in DO are indicated in green while key differences are highlighted in red. b, DR1 residues that form conserved hydrogen bonds to the peptide backbone. Each chain contributes three residues, DRα S53, N62 and N69 as well as DRβ W61, H81 and N82. DR1 is shown as a ribbon representation on the left and as a space-filling model on the right; the peptide is shown as a stick model. Residues that form hydrogen bonds to the peptide are colored as in (a). c, Structure of the DO groove in the DO-DM complex. DOβ residues W61, H81 and N82 are conserved with DR1, but substitutions at DOα positions 53, 62 and 69 result in loss of hydrogen bond donors to a potential peptide. Furthermore, DOα H69 and R53 shorten the groove, with DOα H69 blocking access to the P9 pocket.

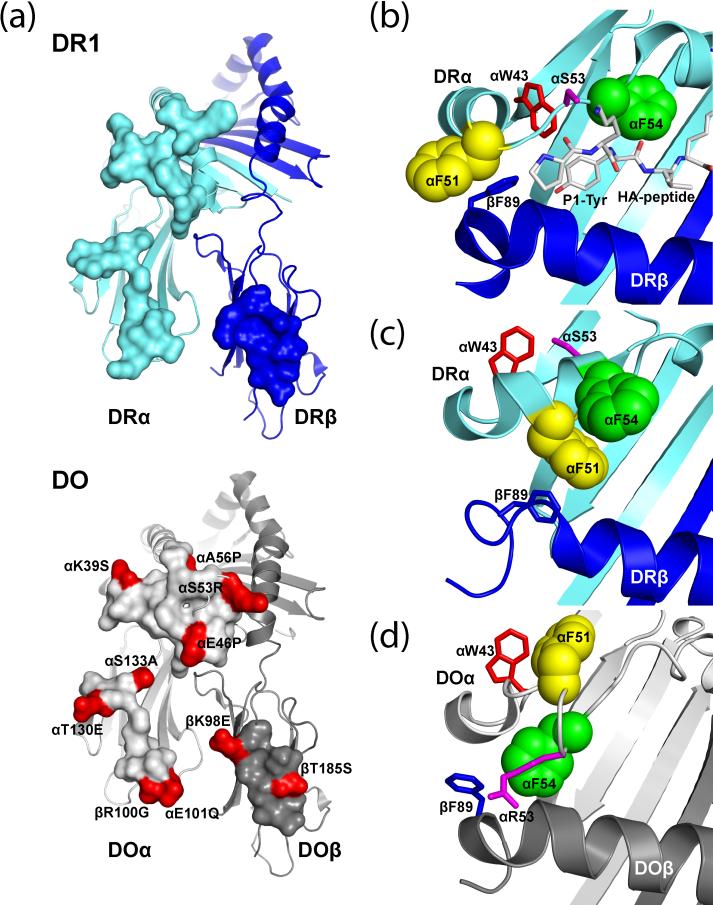

What is the biological significance of these findings? Peptide binding induces dissociation of DR-DM complexes, as described above, yet DM forms stable, long-lived complexes with DR molecules in the absence of peptide [9, 14]. We therefore propose that DO-DM complexes are much more stable because they cannot be disrupted by peptide binding in the groove. Amino acid differences at interface residues (Figure 4) may also increase the affinity of DO for DM, compared to DR and DM.

Figure 4. Differences in the interaction of DR1 and DO with DM.

a, Comparison of the DM interaction surface on DR1 (top) and DO (bottom). Residues that interact with DM are rendered as surfaces. DR chains are colored cyan (α) and blue (β), while DO chains are colored light grey (α) and dark grey (β). A total of 10 DM interacting residues differ between DR and DO, which are highlighted in red on the DO surface. b-d, Differences in the arrangement of key aromatic residues in the DR and DO groove. When a peptide is bound in the DR1 groove, DRα 43 interacts with the P1 tyrosine side chain (Tyr) while DRα F51 points out of the groove (b). In the DR1-DM complex, DRα F51 has moved into the hydrophobic P1 pocket where it is stabilized by DRα F54 and DRβ F89. DRα W43 has rotated away from the P1 pocket and interacts with DM (c). In the DO-DM complex, DOα F51 is not located in the groove, but rather at the interface with DM. The flexible conformation of DOα 47–55 results in placement of DOα F54 in the groove and interaction of DOα R53 with the DOβ chain helix (d). Key aromatic residues (αF51 and F54) are rendered as space-filling models while all other residues are shown as stick models.

How does DM interact with DR or DO?

DO functions as a competitive and essentially irreversible inhibitor of DM activity. DM is expressed at a higher level than DO, which results in a mix of free DM (active) and DM –DO complexes (inactive) [20]. As a substrate mimic, DO interacts with a similar surface of DM as DR1. However, DR1 and DO differ at a number of positions at their interface with DM (Figure 4). A conserved feature among DO-DM and DR1-DM complexes is the interaction between DR and DOα W43 with DMα N125 [17, 25]. However, there are a number of major differences between the structures in the DR and DO α1 domains that interacts with DM. A comparison to the DR1-HA peptide complex shows that the DRα 46-55 segment folds into a helical conformation in the DR-DM complex while a large part of this region lacks a defined secondary structure in the DO-DM complex (Figure 4). This has a direct impact on their interface formed with DM: in the DR1-DM complex DRα F51 occupies the hydrophobic P1 pocket, while the corresponding DO residue interacts with DM. DOα F54 is located in the hydrophobic area between the DOα1 and DOβ1 helices, rather than α F51. These differences may also contribute to the stability of DO-DM complexes.

Relevance to peptide selection by MHC class I molecules

Both MHC class I and class II molecules are highly unstable in the absence of peptide. In fact, recombinant MHC class I (MHCI) molecules can only be refolded from the relevant subunits (extracellular domain of MHCI heavy chain and β2-microglobulin) in the presence of a peptide. Even though MHCI and MHCII proteins acquire peptides in different compartments and utilize different proteins to facilitate the loading process, there are important similarities in the general requirements for peptide acquisition. The MHCI heavy chain associates with β2-microglobulin in the ER, and this complex is then incorporated into the ‘peptide loading complex’ [3]. A critical component of the peptide loading complex is tapasin, which recruits nascent MHCI molecules to the TAP heterodimer responsible for peptide transport into the ER. Tapasin forms a disulfide-linked dimer with ERp57, and this heterodimer performs critical functions in peptide loading of MHCI molecules. In fact, the function of the tapasin-ERp57 heterodimer is analogous to the action of DM: it stabilizes ‘empty’ MHCI molecules in a highly peptide-receptive conformation and thereby greatly accelerates peptide binding. Interestingly, it also promotes selection of high-affinity peptides through an editing process. The most interesting aspect is that binding of high-affinity peptides to such empty MHCI molecules results in dissociation of MHCI-peptide from tapasin [3]. This feature is reminiscent to the action of high-affinity peptides on the DM-DR complex described above. Thus, key principles of the peptide loading process are remarkably similar for MHCI and MHCII molecules: 1. dedicated chaperones stabilize empty molecules and accelerate peptide binding; 2. rapid peptide exchange (editing) favors acquisition of high-affinity peptides; and 3. such peptides induce dissociation from the peptide loading complex.

The crystal structure of the tapasin-ERp57 heterodimer has been determined and key residues for interaction with MHCI molecules have been identified. The tapasin-ERp57 heterodimer appears to stabilize the N-terminal part of the α2 helix of MHCI molecules (which flanks the C-terminal part of peptides) [27]. Other studies have implicated structural changes in the area occupied by the peptide N-terminus in a MHCI-peptide complex. In particular, monoclonal antibodies have been identified that bind only to apparently empty but not peptide-filled MHCI molecules. One of these antibodies (mAb 64-3-7) recognizes a short peptide segment of the MHCI heavy chain (residues 46-52) in the vicinity of the peptide N-terminus. In the peptide-loaded state, a conserved tryptophan residue (W51) and M52 buttress invariant tyrosine residues (Y59 and Y171) at the amino-terminal end of the peptide binding groove. W51 and M52 become solvent-exposed in the peptide-receptive form, apparently by movement of the 310 helix that contains W51 and M52 [28]. Conformational changes (possibly at both ends of the MHCI groove) may favor rapid peptide exchange, as described above for the DR1-DM complex. Binding of high-affinity peptides may reverse these conformational changes and induce release from the MHCI peptide loading complex.

Relevance to pathogenesis of autoimmunity

A substantial number of polymorphic HLA-DQ and HLA-DP residues are located at the putative interface with DM. It has already been shown that HLA-DQ2, which is associated with susceptibility to type 1 diabetes and celiac disease interacts poorly with DM [11, 29, 30]. This raises the question whether insufficient editing of low-affinity peptides may predispose to certain autoimmune diseases. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that key T cell epitopes in animal models of type 1 diabetes and multiple sclerosis bind with very low affinity to the relevant MHCII proteins [31-34]. T cells specific for such peptides escape deletion in the thymus and can be activated by abundant self-antigen present in the target organ, such as insulin in pancreatic islets (type 1 diabetes) or myelin basic protein in the CNS white matter (multiple sclerosis). The efficiency of DM-catalyzed peptide editing may therefore be relevant to the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases.

Concluding remarks

These results provide a structural foundation for understanding key processes in antigen presentation by MHCII molecules. It has long been thought that DM forces peptide dissociation by changing the conformation of MHCII-peptide complexes. The new studies reveal that DM only binds to a short-lived transition state in which part of the MHCII groove is already empty. DM stabilizes this site and favors a rapid exchange process for selection of the highest-affinity ligands. This process removes many low-affinity peptides and thereby drastically changes the peptide repertoire. Alterations in the efficiency of peptide selection may contribute to autoimmune pathologies, which will be an exciting area for future investigation. The structures of DR1-DM and DO-DM complexes may also enable novel strategies for targeting of this pathway for therapeutic benefit.

Highlights.

HLA-DM stabilizes empty HLA-DR1 through major conformational changes of the groove

These conformational changes enable a rapid peptide selection process

HLA-DO acts as a substrate mimic that blocks HLA-DM activity

HLA-DO lacks key residues required for stable peptide binding

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Melissa J. Call, Monika-Sarah E. D. Schulze, Anne-Kathrin Anders, Jason Pyrdol and Eric J. Sundberg for their important contributions to work reviewed here. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (RO1 NS044914 and PO1 AI045757 to K.W.W.), postdoctoral fellowships from The National Multiple Sclerosis Society (D.K.S.) and the American Diabetes Association (W.P.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jenkins MK, Moon JJ. The role of naive T cell precursor frequency and recruitment in dictating immune response magnitude. Journal of immunology. 2012;188:4135–4140. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stern LJ, et al. Crystal structure of the human class II MHC protein HLA-DR1 complexed with an influenza virus peptide. Nature. 1994;368:215–221. doi: 10.1038/368215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blum JS, et al. Pathways of antigen processing. Annual review of immunology. 2013;31:443–473. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-095910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schulze MS, Wucherpfennig KW. The mechanism of HLA-DM induced peptide exchange in the MHC class II antigen presentation pathway. Current opinion in immunology. 2012;24:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Busch R, et al. Achieving stability through editing and chaperoning: regulation of MHC class II peptide binding and expression. Immunological reviews. 2005;207:242–260. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pashine A, et al. Interaction of HLA-DR with an acidic face of HLA-DM disrupts sequence-dependent interactions with peptides. Immunity. 2003;19:183–192. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00200-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris P, et al. An essential role for HLA-DM in antigen presentation by class II major histocompatibility molecules. Nature. 1994;368:551–554. doi: 10.1038/368551a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patil NS, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis (RA)-associated HLA-DR alleles form less stable complexes with class II-associated invariant chain peptide than non-RA-associated HLA-DR alleles. Journal of immunology. 2001;167:7157–7168. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.12.7157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kropshofer H, et al. HLA-DM acts as a molecular chaperone and rescues empty HLA-DR molecules at lysosomal pH. Immunity. 1997;6:293–302. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80332-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sant AJ, et al. The relationship between immunodominance, DM editing, and the kinetic stability of MHC class II:peptide complexes. Immunological reviews. 2005;207:261–278. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Busch R, et al. On the perils of poor editing: regulation of peptide loading by HLA-DQ and H2-A molecules associated with celiac disease and type 1 diabetes. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2012;14:e15. doi: 10.1017/erm.2012.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lovitch SB, et al. Cutting edge: H-2DM is responsible for the large differences in presentation among peptides selected by I-Ak during antigen processing. J Immunol. 2003;171:2183–2186. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.5.2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doebele CR, et al. Determination of the HLA-DM interaction site on HLA-DR molecules. Immunity. 2000;13:517–527. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anders AK, et al. HLA-DM captures partially empty HLA-DR molecules for catalyzed removal of peptide. Nature immunology. 2011;12:54–61. doi: 10.1038/ni.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weber DA, et al. Enhanced dissociation of HLA-DR-bound peptides in the presence of HLA-DM. Science. 1996;274:618–620. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5287.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sadegh-Nasseri S, et al. How HLA-DM works: recognition of MHC II conformational heterogeneity. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2012;4:1325–1332. doi: 10.2741/s334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pos W, et al. Crystal Structure of the HLA-DM-HLA-DR1 Complex Defines Mechanisms for Rapid Peptide Selection. Cell. 2012;151:1557–1568. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weber DA, et al. Transmembrane domain-mediated colocalization of HLA-DM and HLA-DR is required for optimal HLA-DM catalytic activity. J Immunol. 2001;167:5167–5174. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.5167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou Z, et al. Cutting edge: HLA-DM functions through a mechanism that does not require specific conserved hydrogen bonds in class II MHC-peptide complexes. J Immunol. 2009;183:4187–4191. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Denzin LK, Cresswell P. Sibling rivalry: competition between MHC class II family members inhibits immunity. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2013;20:7–10. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Draghi NA, Denzin LK. H2-O, a MHC class II-like protein, sets a threshold for B-cell entry into germinal centers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:16607–16612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004664107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van den Hoorn T, et al. Routes to manipulate MHC class II antigen presentation. Current opinion in immunology. 2011;23:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yi W, et al. Targeted regulation of self-peptide presentation prevents type I diabetes in mice without disrupting general immunocompetence. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2010;120:1324–1336. doi: 10.1172/JCI40220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gu Y, et al. Immunodeficiency and autoimmunity in H2-O-deficient mice. Journal of immunology. 2013;190:126–137. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guce AI, et al. HLA-DO acts as a substrate mimic to inhibit HLA-DM by a competitive mechanism. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:90–98. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoon T, et al. Mapping the HLA-DO/HLA-DM complex by FRET and mutagenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:11276–11281. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113966109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dong G, et al. Insights into MHC class I peptide loading from the structure of the tapasin-ERp57 thiol oxidoreductase heterodimer. Immunity. 2009;30:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mage MG, et al. The peptide-receptive transition state of MHC class I molecules: insight from structure and molecular dynamics. Journal of immunology. 2012;189:1391–1399. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fallang LE, et al. Complexes of two cohorts of CLIP peptides and HLA-DQ2 of the autoimmune DR3-DQ2 haplotype are poor substrates for HLA-DM. Journal of immunology. 2008;181:5451–5461. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hou T, et al. An insertion mutant in DQA1*0501 restores susceptibility to HLA-DM: implications for disease associations. Journal of immunology. 2011;187:2442–2452. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mohan JF, Unanue ER. A novel pathway of presentation by class II-MHC molecules involving peptides or denatured proteins important in autoimmunity. Molecular immunology. 2013;55:166–168. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2012.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stadinski BD, et al. Diabetogenic T cells recognize insulin bound to IAg7 in an unexpected, weakly binding register. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:10978–10983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006545107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mohan JF, et al. Register shifting of an insulin peptide-MHC complex allows diabetogenic T cells to escape thymic deletion. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2011;208:2375–2383. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sabatino JJ, Jr., et al. Manipulating antigenic ligand strength to selectively target myelin-reactive CD4+ T cells in EAE. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2010;5:176–188. doi: 10.1007/s11481-009-9181-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]