Abstract

According to the social defeat (SD) hypothesis, published in 2005, long-term exposure to the experience of SD may lead to sensitization of the mesolimbic dopamine (DA) system and thereby increase the risk for schizophrenia. The hypothesis posits that SD (ie, the negative experience of being excluded from the majority group) is the common denominator of 5 major schizophrenia risk factors: urban upbringing, migration, childhood trauma, low intelligence, and drug abuse. The purpose of this update of the literature since 2005 is to answer 2 questions: (1) What is the evidence that SD explains the association between schizophrenia and these risk factors? (2) What is the evidence that SD leads to sensitization of the mesolimbic DA system? The evidence for SD as the mechanism underlying the increased risk was found to be strongest for migration and childhood trauma, while the evidence for urban upbringing, low intelligence, and drug abuse is suggestive, but insufficient. Some other findings that may support the hypothesis are the association between risk for schizophrenia and African American ethnicity, unemployment, single status, hearing impairment, autism, illiteracy, short stature, Klinefelter syndrome, and, possibly, sexual minority status. While the evidence that SD in humans leads to sensitization of the mesolimbic DA system is not sufficient, due to lack of studies, the evidence for this in animals is strong. The authors argue that the SD hypothesis provides a parsimonious and plausible explanation for a number of epidemiological findings that cannot be explained solely by genetic confounding.

Key words: genetics, epidemiology, dopamine, social exclusion, migration, intelligence

Introduction

In 2005, following the principle of Occam’s razor, we sought a common denominator for well-established risk factors of schizophrenia (migration, urban upbringing, low IQ, childhood trauma, and illicit drug use) and hypothesized that long-term exposure to the experience of social defeat (SD) or social exclusion (SE) may lead to sensitization of the mesolimbic dopamine (DA) system (and/or increased baseline activity of this system) and thereby increase the risk for schizophrenia.1,2 Sensitization is a process whereby exposure to a given stimulus, such as a drug or a stressor, results in an enhanced response (here: DA response) to subsequent exposures. The purpose of this article is to examine the current utility of the hypothesis. We review pertinent investigations published after 2005 and discuss some findings that have not been discussed within this context before 2005. We tried to answer the following questions: (1) What is the evidence that “long-term exposure to the experience of SD or SE” explains the association between schizophrenia and the above-mentioned 5 risk factors? Are there other epidemiological findings that support or refute the SD hypothesis? (2) What is the evidence from studies in humans that SD leads to increased baseline activity and/or sensitization of the mesolimbic DA system? (3) What is the evidence from animal studies that SD leads to dopaminergic abnormalities? (4) Is SD a cause of schizophrenia?

Conceptual Issues

Although SD and SE are different terms, we aim at one type of exposure, namely the negative experience of being excluded from the majority group. This experience is not a specific cause of schizophrenia because many people exposed to it develop other psychiatric disorders, and it is unlikely to be a necessary or sufficient cause.

How does the SD hypothesis relate to other hypotheses in the field? Collip et al3 proposed that “environmental exposures induce psychological or physiological alterations that can be traced to a final common pathway of cognitive biases and/or altered DA neurotransmission, broadly referred to as ‘sensitization’, facilitating the onset and persistence of psychotic symptoms.” Morgan et al4 suggested a role for cumulative social disadvantage and Hoffman5 formulated a social deafferentation hypothesis.

Firstly, because the sensitization hypothesis put forward by Collip et al3 does not identify specific stressors, it concerns pathogenesis rather than etiology. The SD hypothesis, in contrast, is about pathogenesis (ie, sensitization of the mesolimbic DA system) and etiology. Collip et al3 understand by sensitization also progressively greater psychological responses to the same stimulus (eg, irritation). Thus, the two hypotheses may complement each other.

Secondly, Morgan et al4 proposed that cumulative social disadvantage in childhood and adulthood increases risk for schizophrenia. The authors identified indicators of social disadvantage in the domains of separation from (or death of) parents, education, employment, living arrangement, housing, relationships, and social networks.6 Thus, the concept of social disadvantage is essentially broader than that of SD and does not specify how social disadvantage translates into increased psychosis risk. In contrast, the SD hypothesis postulates that indicators of social disadvantage may act as proxies for SD, provided that the subject interprets the situation as defeating. This is important, because no evidence exists that populations in low-income countries are at increased risk, and low socioeconomic status (SES) of the parents is generally not a risk factor for schizophrenia.7

Finally, Hoffman5 hypothesized that high levels of isolation prompt the social brain to produce spurious social meaning in the form of hallucinations and delusions representing other persons or agents. This social deafferentation hypothesis capitalizes on the principle that the brain, if deprived from input of information, will produce this information by itself. Thus, this hypothesis postulates that isolation is a risk factor by itself, while the SD hypothesis requires isolation to occur in a context of defeat.

Measurement

The experience of SD is difficult to measure, because humans use strategies to keep up appearances. For that reason, the SD hypothesis is mainly based on epidemiological studies that compared defeated and nondefeated groups (not individuals). Alternative measurements include firstly the use of questionnaires such as the Social Comparison Scale,8 the Defeat Scale,9 and the Brief Core Schema Scales.10 Secondly, one can use momentary assessment techniques,11 or, since exclusion from the majority group will often lead to low self-esteem, tests for the measurement of implicit self-esteem.12 Thirdly, one can simulate SE or negative evaluation in a laboratory situation13 although the short duration of exposure is a drawback.

Evidence That SD Explains Association With Urban Upbringing

What is the evidence that higher levels of competition in urban areas, and correspondingly more frequent exposure to SD, explain the association between urban upbringing and risk for schizophrenia? A functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study examined the impact of urban upbringing and current city living on social evaluative stress processing in the brain.13 The researchers subjected psychologically healthy participants to the Montreal Imaging Stress Task (MIST), which requires individuals to solve arithmetic tasks under pressure of time and negative feedback. The results showed that current city living was associated with increased amygdala activity, whereas urban upbringing affected the perigenual anterior cingulate cortex. No urbanicity effect was seen during control experiments invoking cognitive processing without stress. Interestingly, the results may provide a neural basis for the epidemiological finding that urban upbringing, rather than current city living, is associated with increased risk for schizophrenia and provide preliminary evidence for SD as the mechanism underlying the association with urban upbringing.

Zammit et al14 examined whether individual, school, or municipality characteristics predicted the psychosis risk for Swedish adolescents. School-level variables included the foreign-born average (proportion of children with 1 or 2 parents born abroad), the social fragmentation average (the proportion of children who migrated into Sweden, moved into a different municipality between ages 8 and 16 years, or were raised in single-parent households), the deprivation average (proportion of children with low SES), and the low- grade average (proportion of children scoring low). Municipality variables included, among others, population density. Interestingly, the results showed strong evidence of interaction between certain variables at the individual level and the same variables at school level. For example, deprivation at the individual level increased psychosis risk when most children at school were not deprived. However, deprivation at the individual level protected against psychosis when the majority of most children at school were deprived. The same was true for the variables foreign birth and social fragmentation but not for low grade. The authors concluded, in line with the SD hypothesis, that any characteristic that defines a person as different from his environment may increase his psychosis risk. In conclusion, the results of the Lederbogen et al13 study suggest a role for SD in the etiology of schizophrenia, but do not yet, of course, establish a causal relationship. The results of the Zammit et al14 study suggest causality more strongly.

Evidence That SD Explains Association With Migration

The SD hypothesis was prompted in part by a meta- analysis of migrant studies, which showed greater effect sizes for migrants from low-income countries and for migrants with black skin color.15 Bourque et al16 found that the increased risk persists into the second generation, suggesting that rather than adverse circumstances during the migration process per se, the minority position in the host society has a more determinant role.

One of the most striking findings in this area is the crossover interaction with ethnic density. In The Hague and London, it was demonstrated that living in a neighborhood with a high proportion of residents of the own ethnic group is related to a lower risk for schizophrenia and low own-group ethnic density to a higher risk.17,18 Das-Munshi et al19 showed that potential markers of SD, such as discrimination, poor social support, and chronic strains, mediated the relationship between low own-group ethnic density and presence of psychotic experiences. Zammit et al14 showed that the ethnic density effect also operates at school level because it similarly applies to children with Swedish parents attending schools with a high proportion of foreign-born children.

A longitudinal study from the Netherlands demonstrated that younger age at migration predicts a higher risk for psychotic disorders among non-Western immigrants, with the most elevated risk among children who migrated between ages 0 and 4 years.20 Remarkably, the risk for migrants arriving at age 20–24 or 25–29 was only modestly increased. Whether these findings support or contradict the SD hypothesis is uncertain. One could both predict a high risk for migrants who arrive in early adulthood and have to cope with difficulties at the labor market and also for migrants who are exposed to discrimination at a very young age. The results must, however, be interpreted with caution, because they could not be replicated using nationwide registry data from Denmark.21

Evidence That SD Explains Association With Low IQ

Low IQ is a well-established risk factor for schizophrenia and several studies attempted to identify common (poly)genetic components between the two phenotypes. Toulopoulou et al22,23 initially reported high (−.75) to moderate (−.38) phenotypic correlations between IQ and schizophrenia, respectively. However, the twin samples of these studies were not population based and IQ was measured after the onset of psychosis. Fowler et al24 avoided these sources of bias and found a weak correlation (−.11) and a shared genetic variance of only 7%.

Goldberg et al25 examined the influence of cognitive abilities and premorbid SES on the risk of hospitalization for schizophrenia. Adolescents with low cognitive ability appeared to have an increased risk for schizophrenia, especially when they grew up in areas with a high SES. The authors argue that the increased risk may be partly conferred by the discrepancy between these high expectations and actual achievements. Nonetheless, the evidence supporting the role of SD in the association between low IQ and schizophrenia is as yet not sufficient.

Evidence That SD Explains Association With Childhood Trauma

Meta-analytic evidence demonstrates consistent patterns of increased incidence of psychotic disorder and subclinical psychotic symptoms in individuals who experienced several types of childhood trauma.26,27 Despite the association being predominantly based on results from retrospective studies susceptible to recall bias, its validity has been strengthened by comparable findings from prospective studies that did not depend on personal recollection.28,29

Childhood trauma encompasses a broad range of adverse experiences. Traumas that involve an intentional harm such as sexual, physical and psychological abuse, and bullying, putatively lead to SD. In other types of childhood trauma, such as accidents or parental loss, SD might not necessarily be as directly implicated. In a longitudinal twin study, risk for psychotic symptoms at age 12 was associated with previous maltreatment by an adult (relative risk [RR] = 3.2, 95% CI = 1.9–5.2) or bullying by peers (RR = 2.5, 95% CI = 1.7–3.5), but much less so with the experience of a lifetime accident (RR = 1.47, 95% CI = 1.0–2.1).28 In line with the SD hypothesis, the relationship between intentionally inflicted childhood trauma and risk of psychotic disorder stresses the putative pathogenic influence of the experience of (chronic) humiliation. Contrarily, parental separation and parental death are types of trauma associated with increased psychosis risk that do not necessarily involve an intention to harm.6,27 However, it is unknown whether these events are causal factors per se or whether they represent markers for family conflicts or instability.

In conclusion, consistent with the SD hypothesis, an increasing body of evidence affirms a true association between childhood trauma and psychotic disorder.

Evidence That SD Explains Association With Illicit Drugs

That people who use illicit drugs are at risk of developing schizophrenia is primarily due to a toxic effect of these substances. However, SD may contribute to the association between drug use and schizophrenia in at least two ways. Firstly, drug abuse often leads to SD. Secondly, SD may lead to drug abuse. Studies have shown a strong association between a history of childhood trauma and subsequent drug abuse30 and between unemployment and drug abuse.31

Other Epidemiological Findings

Risk for schizophrenia is associated with single status. While there may be many reasons for being unmarried, this may act as a stressor. The same considerations apply to unemployment. There are reports of an increased risk for schizophrenia among people with a hearing impairment.32 Earlier reports of no association between autistic spectrum disorders and schizophrenia are now superseded by reports of an increased risk.33 There is evidence that autism and schizophrenia share genes, but SD may contribute to the increased risk. Traumatic brain injury is associated with an increased risk for schizophrenia.34 It would be interesting to examine whether psychosis develops especially in those patients who lose their status. Klinefelter syndrome, characterized by small genitals and infertility, is associated with an excessive risk for schizophrenia.35 An investigation of the Danish psychiatric registry found no significantly increased risk for schizophrenia among people with a cleft palate, but this may have been due to insufficient power of the study.36 With reference to discriminated minorities, during the period 1935–1965, there have been consistent reports of an increased risk for schizophrenia among African Americans.37 More recent studies seem to confirm the earlier findings of a 2- to 3-fold elevated risk.38,39 One could argue that the low prevalence of schizophrenia among a religious minority in North America, the Hutterites, argues against the hypothesis, but this group is known for its social cohesion.40 As for sexual minorities, population surveys reported an increased risk of psychotic symptoms among people with a homosexual orientation41 and there is preliminary evidence of an increased risk among people with a gender identity disorder.42 Other findings include the high prevalence of schizophrenia among illiterates in China, who experience discrimination,43 and the negative association between tallness and risk for schizophrenia among Swedish recruits.44

Evidence That SD in Humans Leads to Sensitization of the Mesolimbic DA System

Positron emission tomography (PET) studies have shown that nonpsychotic subjects who report a low level of maternal care in early life release more DA after exposure to the MIST.45,46 Another PET study using the MIST showed that neuroleptic-naive patients and clinical high-risk subjects also exhibit a sensitized dopaminergic response.47 The negative feedback on performance, which characterizes the MIST, seems to be essential, because a mathematic stress task without negative feedback yielded negative results.48 There have been no studies of DA function in migrants, people raised in cities, people with low IQ, or traumatized people. To summarize, the association between low- perceived maternal care and stress-related DA function and the importance of negative feedback as stressor support the SD hypothesis, but the evidence on a whole is insufficient.

Evidence From Animal Studies That SD Leads to Sensitization of Mesolimbic DA System

Several lines of experimental research have shown that the psychosocial environment, and chronic stress in particular, can mediate changes in gene expression, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, mesolimbic DA neurotransmission, and behavior. Firstly, Meaney and Szyf49 have shown that parental care during early life of rodents induces long-term behavioral and neurobiological alterations, with offspring of low-nurturing mothers showing more signs of anxiety and stronger corticosterone responses after stress exposure, while expressing lower levels of the glucocorticoid receptor in the hippocampus in adulthood. Additional experiments indicated that epigenetic mechanisms mediated these alterations, whereas further animal studies have shown intricate cross talk between the HPA axis and mesolimbic dopaminergic transmission circuitries in relation to chronic stress.50,51

With respect to chronic SD stress, several animal studies using resident-intruder paradigms for modeling the effects of SD stress exposure have found strong indications that SD leads to dopaminergic hyperactivity, particularly in the mesolimbic dopaminergic neurotransmission system52 and to behavioral sensitization.53 Interestingly, the effects of SD on the dopaminergic system seem to depend on environmental circumstances after the defeat. For example, Isovich et al54 found that SD-induced alterations in the binding capacity of the DA transporter depended on the housing conditions after the defeat experience; ie, social isolation after the defeat amplified the alterations, whereas more social housing, ie, return to the same group as before the defeat, mitigated the changes.

It is important to note that the severe physical and social stress to experimental mice cannot directly be compared with the SD experience as occurring in everyday life of humans. Nevertheless, experimental SD exposure in rodents has been shown to induce striking alterations in anxiety-like behavior, prolonged elevations in corticosterone levels, and a range of other molecular, cellular, and behavioral changes55 such as alterations in neurogenesis,56 besides the above-mentioned effects on dopaminergic transmission and behavioral sensitization.

Accumulating evidence indicates that chronic SD paradigms elicit a striking differential susceptibility in social behavior as well as in distinct neurobiological phenotypes of SD-exposed mice.55 At the behavioral level, one group of mice displays social avoidance after the SD experience (these mice are called “susceptible”) and signs of anhedonia, while a second group of mice still shows social interaction rates that are comparable with the control group (and is therefore called “unsusceptible” or “resilient”). At the neurobiological level, the susceptible mice display increased firing rates of dopaminergic ventral tegmental area (VTA) neurons (ie, the mesolimbic system, particularly those projecting to the nucleus accumbens),57 connected to upregulated voltage-gated K+ channels and epigenetic aberrations of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene, while unsusceptible mice displayed normal firing rate of dopaminergic VTA neurons.55

Thus, findings from animal studies are providing strong and replicated evidence that SD increases baseline activity of the mesolimbic dopaminergic system and induces sensitization of DA-related behavioral, electrophysiological, and neurochemical features, while the more recent studies also illustrate that animals may strongly differ in DA-related effects of SD exposure, that chronic stress-induced alterations of the HPA axis are connected to dopaminergic alteration, and that the differential susceptibility to SD may be (at least in part) of epigenetic origin.

Is SD a Cause of Schizophrenia?

Before addressing this question, we will respond to the following criticisms: (1) the association between SD and schizophrenia is due to genetic confounding and (2) SD is not a specific risk factor for schizophrenia.

An explanation in terms of genetic confounding assumes that people who are genetically predisposed to schizophrenia move to urban areas because they prefer to live in anonymity, emigrate because they fail to integrate in their home country, are victimized during childhood because of their poor social skills, and use illicit drugs because they are unhappy. In other words, SD is the consequence, not the cause. This explanation meets with at least four challenges. Firstly, there is little supportive evidence.15,27 Secondly, the explanations do not allow for the possibility that causality operates in both directions. Individuals genetically predisposed to schizophrenia, eg, may be more likely to use illicit drugs, but this does not preclude a toxic effect of these drugs. Thirdly, some assumptions are contradictory: children who carry genes for schizophrenia are presumed to be socially vulnerable, but migrants are enterprising and constitute a positive selection in terms of physical health.58 Finally, the genetic confounding hypothesis rests on too many unproven assumptions: certain genes cause schizophrenia and the same genes also cause their carriers to move to cities, to emigrate, to use drugs, to be bullied, and to be victimized.

As for the issue of specificity, risk factors are rarely specific for a particular psychiatric disorder.59

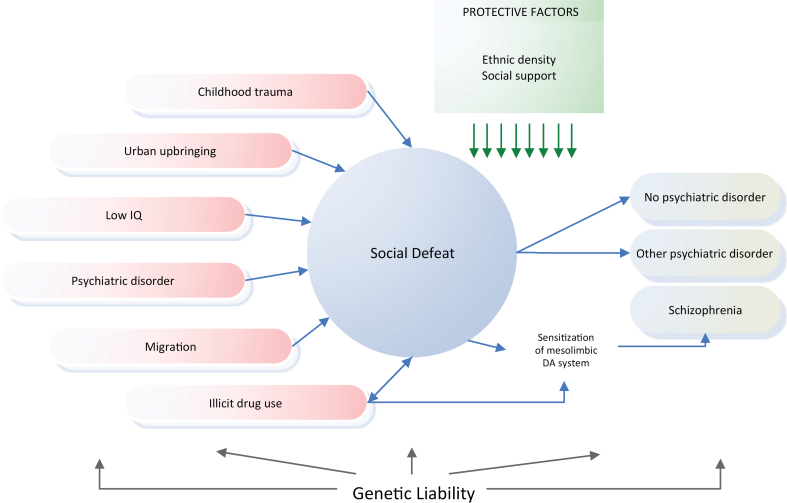

We conclude that the SD hypothesis provides a more parsimonious and therefore more plausible explanation for the schizophrenia risk pattern than an explanation solely in terms of genetic confounding. Moreover, it may explain why a large part of the genome is involved in etiology, because any change in a gene that renders the carrier more prone to SD will influence his risk. Another corollary of the SD hypothesis is that the presence of any mental disorder will increase the patient’s risk for schizophrenia, because having a mental disorder is usually associated with a degree of SE. The literature provides support for this idea: mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders are common precursors for schizophrenia.60,61 See figure 1 for a schematic illustration.

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of the experience of social defeat as the common mechanism underlying 6 major schizophrenia risk factors.

In sum, the evidence for the first part of the SD hypothesis (SD is the common denominator for the 5 major risk factors) is fairly strong and we contend that long-term exposure to SD is a cause of schizophrenia indeed. The evidence for the second part of the hypothesis (SD leads to DA dysregulation), however, is insufficient.

Future Studies

Hypotheses should be evaluated by subjecting them to crucial tests. There are many possibilities. For example, our prediction that a study of ethnic subgroups within the Israeli population would find the highest risk for Ethiopian Jews was confirmed.1,62 Future studies could examine whether people with a genetic risk for schizophrenia react differently to simulated SE using fMRI and investigate which (epi)genetic profiles are associated with susceptibility to SD. Neuroreceptor imaging studies can examine DA response during stressful circumstances and DA function in high-risk groups. Thus, the SD hypothesis seems to provide many promising avenues for investigating epidemiological patterns that are still lacking a satisfactory explanation.

Funding

European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme under grant agreement no. HEALTH-F2-2010-241909 (Project EU-GEI).

Acknowledgments

We thank James Kirkbride for very useful comments. The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

References

- 1. Selten JP, Cantor-Graae E. Social defeat: risk factor for schizophrenia? Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:101–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Selten JP, Cantor-Graae E. Hypothesis: social defeat is a risk factor for schizophrenia? Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2007;51:s9–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Collip D, Myin-Germeys I, Van Os J. Does the concept of “sensitization” provide a plausible mechanism for the putative link between the environment and schizophrenia? Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:220–225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Morgan C, Kirkbride J, Hutchinson G, et al. Cumulative social disadvantage, ethnicity and first-episode psychosis: a case- control study. Psychol Med. 2008;38:1701–1715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hoffman RE. A social deafferentation hypothesis for induction of active schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:1066–1070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stilo SA, Di Forti M, Mondelli V, et al. Social disadvantage: cause or consequence of impending psychosis? Schizophr Bull. October 22, 2012;10.1093/schbul/sbs112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Byrne M, Agerbo E, Eaton WW, Mortensen PB. Parental socio-economic status and risk of first admission with schizophrenia - a Danish national register based study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39:87–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Allan S, Gilbert P. A social comparison scale: psychometric properties and relationship to psychopathology. Person Individ Diff. 1995;19:293–299 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gilbert P, Allan S. The role of defeat and entrapment (arrested flight) in depression: an exploration of an evolutionary view. Psychol Med. 1998;28:585–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fowler D, Freeman D, Smith B, et al. The Brief Core Schema Scales (BCSS): psychometric properties and associations with paranoia and grandiosity in non-clinical and psychosis samples. Psychol Med. 2006;36:749–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Myin-Germeys I, Oorschot M, Collip D, Lataster J, Delespaul P, van Os J. Experience sampling research in psychopathology: opening the black box of daily life. Psychol Med. 2009;39:1533–1547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Greenwald AG, Farnham SD. Using the implicit association test to measure self-esteem and self-concept. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;79:1022–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lederbogen F, Kirsch P, Haddad L, et al. City living and urban upbringing affect neural social stress processing in humans. Nature. 2011;474:498–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zammit S, Lewis G, Rasbash J, Dalman C, Gustafsson JE, Allebeck P. Individuals, schools, and neighborhood: a multilevel longitudinal study of variation in incidence of psychotic disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:914–922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cantor-Graae E, Selten JP. Schizophrenia and migration: a meta-analysis and review. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:12–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bourque F, van der Ven E, Malla A. A meta-analysis of the risk for psychotic disorders among first- and second- generation immigrants. Psychol Med. 2011;41:897–910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kirkbride JB, Jones PB, Ullrich S, Coid JW. Social deprivation, inequality, and the neighborhood-level incidence of psychotic syndromes in East London. Schizophr Bull. December 12, 2012;10.1093/schbul/sbs151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Veling W, Susser E, van Os J, Mackenbach JP, Selten JP, Hoek HW. Ethnic density of neighborhoods and incidence of psychotic disorders among immigrants. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:66–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Das-Munshi J, Bécares L, Boydell JE, et al. Ethnic density as a buffer for psychotic experiences: findings from a national survey (EMPIRIC). Br J Psychiatry. 2012;201:282–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Veling W, Hoek HW, Selten JP, Susser E. Age at migration and future risk of psychotic disorders among immigrants in the Netherlands: a 7-year incidence study. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:1278–1285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pedersen CB, Cantor-Graae E. Age at migration and risk of schizophrenia among immigrants in Denmark: a 25-year incidence study. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:1117–1118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Toulopoulou T, Picchioni M, Rijsdijk F, et al. Substantial genetic overlap between neurocognition and schizophrenia: genetic modeling in twin samples. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1348–1355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Toulopoulou T, Goldberg TE, Mesa IR, et al. Impaired intellect and memory: a missing link between genetic risk and schizophrenia? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:905–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fowler T, Zammit S, Owen MJ, Rasmussen F. A population-based study of shared genetic variation between premorbid IQ and psychosis among male twin pairs and sibling pairs from Sweden. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:460–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Goldberg S, Fruchter E, Davidson M, Reichenberg A, Yoffe R, Weiser M. The relationship between risk of hospitalization for schizophrenia, SES, and cognitive functioning. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:664–670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Matheson SL, Shepherd AM, Pinchbeck RM, Laurens KR, Carr VJ. Childhood adversity in schizophrenia: a systematic meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2013;43:225–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Varese F, Smeets F, Drukker M, et al. Childhood adversities increase the risk of psychosis: a meta-analysis of patient- control, prospective- and cross-sectional cohort studies. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:661–671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Arseneault L, Cannon M, Fisher HL, Polanczyk G, Moffitt TE, Caspi A. Childhood trauma and children’s emerging psychotic symptoms: A genetically sensitive longitudinal cohort study. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:65–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cutajar MC, Mullen PE, Ogloff JR, Thomas SD, Wells DL, Spataro J. Schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders in a cohort of sexually abused children. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:1114–1119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Simpson TL, Miller WR. Concomitance between childhood sexual and physical abuse and substance use problems. A review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2002;22:27–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Henkel D. Unemployment and substance use: a review of the literature (1990-2010). Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2011;4:4–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. van der Werf M, Thewissen V, Dominguez MD, Lieb R, Wittchen H, van Os J. Adolescent development of psychosis as an outcome of hearing impairment: a 10-year longitudinal study. Psychol Med. 2011;41:477–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Howlin P. Outcome in high-functioning adults with autism with and without early language delays: implications for the differentiation between autism and Asperger syndrome. J Autism Dev Disord. 2003;33:3–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Molloy C, Conroy RM, Cotter DR, Cannon M. Is traumatic brain injury a risk factor for schizophrenia? A meta-analysis of case-controlled population-based studies. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:1104–1110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bruining H, Swaab H, Kas M, van Engeland H. Psychiatric characteristics in a self-selected sample of boys with Klinefelter syndrome. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e865–e870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Christensen K, Mortensen PB. Facial clefting and psychiatric diseases: a follow-up of the Danish 1936-1987 Facial Cleft cohort. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2002;39:392–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Selten JP, Cantor-Graae E. Schizophrenia and migration. In: Gattaz W, Häfner H, eds. Search for the Causes of Schizophrenia. Vol V Darmstadt, Germany: Steinkopff/Springer; 2004:3–25 [Google Scholar]

- 38. Minsky S, Vega W, Miskimen T, Gara M, Escobar J. Diagnostic patterns in Latino, African American, and European American psychiatric patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:637–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bresnahan M, Begg MD, Brown A, et al. Race and risk of schizophrenia in a US birth cohort: another example of health disparity? Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:751–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nimgaonkar VL, Fujiwara TM, Dutta M, et al. Low prevalence of psychoses among the Hutterites, an isolated religious community. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1065–1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gevonden MJ, Selten JP, Myin-Germeys I, et al. Sexual minority status and psychotic symptoms: findings from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Studies (NEMESIS). Psychol Med. 2013:1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. à Campo J, Nijman H, Merckelbach H, Evers C. Psychiatric comorbidity of gender identity disorders: a survey among Dutch psychiatrists. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1332–1336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Liu T, Song X, Chen G, et al. Illiteracy and schizophrenia in China: a population-based survey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48:455–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zammit S, Rasmussen F, Farahmand B, et al. Height and body mass index in young adulthood and risk of schizophrenia: a longitudinal study of 1 347 520 Swedish men. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;116:378–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Soliman A, O’Driscoll GA, Pruessner J, et al. Stress-induced dopamine release in humans at risk of psychosis: a [11C]raclopride PET study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:2033–2041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pruessner JC, Champagne F, Meaney MJ, Dagher A. Dopamine release in response to a psychological stress in humans and its relationship to early life maternal care: a positron emission tomography study using [11C]raclopride. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2825–2831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mizrahi R, Addington J, Rusjan PM, et al. Increased stress-induced dopamine release in psychosis. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71:561–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Montgomery AJ, Mehta MA, Grasby PM. Is psychological stress in man associated with increased striatal dopamine levels? A [11C]raclopride PET study. Synapse. 2006;60:124–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Meaney MJ, Szyf M. Environmental programming of stress responses through DNA methylation: life at the interface between a dynamic environment and a fixed genome. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2005;7:103–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lemos JC, Wanat MJ, Smith JS, et al. Severe stress switches CRF action in the nucleus accumbens from appetitive to aversive. Nature. 2012;490:402–406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Weaver IC, Cervoni N, Champagne FA, et al. Epigenetic programming by maternal behavior. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:847–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tidey JW, Miczek KA. Social defeat stress selectively alters mesocorticolimbic dopamine release: an in vivo microdialysis study. Brain Res. 1996;721:140–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Covington HE, 3rd, Miczek KA. Repeated social-defeat stress, cocaine or morphine. Effects on behavioral sensitization and intravenous cocaine self-administration “binges”. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2001;158:388–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Isovich E, Engelmann M, Landgraf R, Fuchs E. Social isolation after a single defeat reduces striatal dopamine transporter binding in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:1254–1256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Krishnan V, Han MH, Graham DL, et al. Molecular adaptations underlying susceptibility and resistance to social defeat in brain reward regions. Cell. 2007;131:391–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Van Bokhoven P, Oomen CA, Hoogendijk WJ, Smit AB, Lucassen PJ, Spijker S. Reduction in hippocampal neurogenesis after social defeat is long-lasting and responsive to late antidepressant treatment. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;33:1833–1840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Chaudhury D, Walsh JJ, Friedman AK, et al. Rapid regulation of depression-related behaviours by control of midbrain dopamine neurons. Nature. 2013;493:532–536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. MacMahon B, Trichopoulos D. Epidemiology: Principles and Methods. 2nd ed Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company; 1996:148–154 [Google Scholar]

- 59. Weiser M, van Os J, Davidson M. Time for a shift in focus in schizophrenia: from narrow phenotypes to broad endophenotypes. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:203–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Tien AY, Eaton WW. Psychopathologic precursors and sociodemographic risk factors for the schizophrenia syndrome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:37–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wigman JT, van Nierop M, Vollebergh WA, et al. Evidence that psychotic symptoms are prevalent in disorders of anxiety and depression, impacting on illness onset, risk, and severity–implications for diagnosis and ultra-high risk research. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:247–257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Weiser M, Werbeloff N, Vishna T, et al. Elaboration on immigration and risk for schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 2008;38:1113–1119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]