Abstract

Background: Medication nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia presents a serious clinical problem. Research on interventions incorporating motivational interviewing (MI) to improve adherence have shown mixed results. Aims: Primary aim is to determine the effectiveness of a MI intervention on adherence and hospitalization rates in patients, with multi-episode schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, who have experienced a psychotic relapse following medication nonadherence. Secondary aim is to evaluate whether MI is more effective in specific subgroups. Methods: We performed a randomized controlled study including 114 patients who experienced a psychotic relapse due to medication nonadherence in the past year. Participants received an adapted form of MI or an active control intervention, health education (HE). Both interventions consisted of 5–8 sessions, which patients received in adjunction to the care as usual. Patients were assessed at baseline and at 6 and 12 months follow-up. Results: Our results show that MI did not improve medication adherence in previously nonadherent patients who experienced a psychotic relapse. Neither were there significant differences in hospitalization rates at follow-up between MI and HE (27% vs 40%, P = .187). However, MI resulted in reduced hospitalization rates for female patients (9% vs 63%, P = .041), non-cannabis users (20% vs 53%, P = .041), younger patients (14% vs 50%, P = .012), and patients with shorter illness duration (14% vs 42%, P = .040). Conclusions: Targeted use of MI may be of benefit for improving medication adherence in certain groups of patients, although this needs further examination.

Key words: RCT, intervention study, medication adherence, motivational interviewing, schizophrenia

Introduction

Nonadherence to antipsychotic medication is highly prevalent in patients with schizophrenia1 and is associated with sharply increased readmission rates, more aggressive incidents, more suicides, significant emotional and social burden for patients and their families, and higher financial costs.2–4 In the last decades, several interventions have been developed to improve adherence rates.5 Recent treatment recommendations promote focusing on specific targets that may contribute to nonadherence.6 Motivational interviewing (MI) is a client-centered, directive method for enhancing intrinsic motivation to change by exploring and resolving ambivalence.7 MI was originally designed as a therapeutic approach to treat abuse of alcohol and other substances, for which it proved to be very effective.8,9 Following positive results in other health care domains with regard to behavior change,10–12 effectiveness of (adapted) MI for improving medication adherence has also been studied in patients with psychotic disorders.5,13 Compliance therapy, an intervention based on MI and other cognitive approaches, showed substantial improvements in medication adherence in patients with schizophrenia,14,15 although this could not be replicated in another trial.16 Studies focusing on a similar intervention (“adherence therapy”), also containing MI, yielded mixed results.17,18

More recently, an individually tailored approach incorporating MI proved to be effective in prompting service engagement and medication adherence.19

This means that to date evidence concerning the effectiveness of MI as a means to improve medication adherence in patients with schizophrenia is still inconclusive.

The present study was designed to investigate the effect of MI on adherence to antipsychotic medication in patients, with a multi-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorder, who were hospitalized or unstable due to medication nonadherence. These so-called “revolving door” patients generally have poor social functioning and an unfavorable prognosis, and therefore improvement of their medication adherence is urgently needed.20 The current study explicitly aimed to include this severely disturbed group of patients, who are often either excluded from studies or are unwilling to participate. To find a possible explanation for the unequivocal results on the effect of MI on adherence so far, a second aim of the study was to investigate whether specific subgroups of patients may benefit more from this intervention than others. As there are several factors associated with nonadherence,1 we aimed to explore whether known risk factors for nonadherence such as cannabis use, illness duration, and route of medication administration, along with gender and age, may mediate effectiveness of MI.

Methods

Participants

The study was conducted in 3 mental health care institutions in the greater Amsterdam area. Participants were selected from inpatient and outpatient facilities for the treatment of psychotic disorders. Clinicians of the participating facilities regularly reviewed their caseloads for patients that showed a psychotic relapse or a clinical deterioration with nonadherence as a probable cause. Next, potential participants were invited to receive information on the study and to verify the following inclusion criteria: an age of 18–65 years, a clinical diagnosis of schizophrenia or a schizoaffective disorder confirmed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM disorders.21 Participants had experienced a recent (<1 y) psychotic relapse and/or a clinical deterioration, both following nonadherence to the antipsychotic treatment, resulting in hospitalization and/or a change on the Clinical Global Impression Scale, severity of illness.22 Subsequently, antipsychotic treatment had to be resumed with at least some symptomatic improvement, defined as score of 1, 2, or 3 (very much improved, much improved, or minimal improved) on the Clinical Global Impression Scale for improvement.22 Participants were required to have an adequate mastery of the Dutch language and be able and prepared to give written informed consent. Exclusion criteria were an organic disease with a possible etiological relation to the psychotic disorder and/or a severe intellectual dysfunction (intelligence quotient <70).

Interventions

Motivational Interviewing.

MI is a client-centered, directive method, through which patients are engaged in strategically directed conversations about their problems. It explores personal ideas and ambivalences, eliciting and selectively reinforcing “change talk,” by which discrepancies between the present behavior and the patient’s own future goals are amplified. The overall goal is to increase the patient’s intrinsic motivation for change.7

Based on the basic principles of MI, a manual was designed, incorporating some adaptations directed at specific problems of the study group, such as negative symptoms, specific positive symptoms (delusions concerning medication) as well as cognitive deficits such as attention problems. In contrast to the original MI, the adapted form therefore encompasses a somewhat more active stance of the therapist, greater flexibility in session length, and a more active provision of psychoeducational information, though only after explicit consent by the patient. MI according to the intervention manual (available upon request from E.B.) comprised 4 phases. These were used as a framework, though not in a strict consecutive order. The phases involved introduction and engagement; exploring attitudes and beliefs toward treatment, exploring the patient’s own personal goals, and the “readiness for change.” In the next phase, information was provided and ambivalences were amplified along which favorable attitudes and beliefs toward change were reinforced. The last phase was committed to evaluation and consolidation of the motivation to change.

Health Education.

The control group was provided Health Education (HE) sessions. HE comprised individual lectures on general health topics (such as healthy food, physical exercise etc.). Participants were asked to choose one of these topics for each session. Therapists delivering HE used an active and didactic attitude with specific scripts to ensure that discussing treatment issues was avoided.

Procedure

Participants were allocated to either the experimental intervention–MI–or the control group–HE–by means of a computerized cluster randomization program, producing a block of codes for every 6 consecutive inclusions, which were one by one revealed by the coordinating researcher. The therapists who performed both interventions were psychologists, a psychiatrist, and community mental health nurses, who were trained by a professional trainer on MI (eight 4-h sessions) as well as on HE (two 4-h sessions) according to a structured manual, to maximize skills and minimize contamination effects between interventions.

Therapy sessions were audiotaped if the patient consented to this, and these tapes were used in monthly supervised 4-hour sessions for all therapists, in which the ongoing interventions were discussed, to ensure treatment fidelity. These sessions were focused on delivering interventions according to the treatment manuals and on preventing contamination of MI to HE.

Within a period of 26 weeks, in both the MI and the HE group, patients were offered 8 sessions of either MI or HE. When the therapist judged there were problems to keep patients engaged in the interventions or in case of practical barriers, fewer sessions were given, with a minimum of 5 sessions. Less than 5 sessions was counted as a dropout. The session duration varied between 20 and 45 minutes, depending on the attention span of the participant during a session. Therapists were not otherwise involved in the treatment of participants. Patients were told they would be allocated to 1 of 2 active interventions and were not told which was the experimental condition. Next to the interventions, participants received care as usual, consisting of functional assertive community treatment for patients treated on an outpatient basis and routine clinical care for hospitalized patients.

Before starting the intervention, a baseline assessment (T0) was performed. Participants were interviewed again after the intervention was completed (T1) and after 6 months follow-up (T2). All assessments were performed by trained psychologists and psychiatrists, who were masked to which condition a patient was allocated; a coordinator assigned the interventions and assessments to different researchers, ensuring that the interventions and the assessments were never performed by researchers appointed in the same facility. Data on interventions and assessments were stored separately.

Participants received a travel expenses compensation of 5 euro for each intervention session or assessment in which they participated. The study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the Academic Medical Centre, Amsterdam.

Assessments

Demographics.

Information on demographic data and prescribed medication were assessed with the Client Sociodemographic and Service Receipt Inventory.23

Primary Outcome.

Medication Adherence

Medication adherence was assessed with the medication adherence questionnaire (MAQ), a 4-item questionnaire with good levels of internal validity and reliability,24 covering the participant’s report on medication adherence; scores range from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating higher levels of adherence. Furthermore, data concerning medication adherence as judged by caregivers and treating physicians were measured by the 5-point adherence item of the life chart schedule (LCS), with scores ranging from 1 to 5, higher scores indicating higher levels of adherence. The LCS yields reliable ratings of the long-term course of schizophrenia.25

Attitudes toward medication were assessed with the Drug Attitude Inventory (DAI). The DAI is a self-report 10-item questionnaire, with a score range of 0–10, higher scores indicating more belief in the personal benefit of the medication. The DAI showed a good internal consistency and validity.26

Secondary Outcomes.

Hospitalization

Hospitalization was assessed by the LCS.25 Based on the LCS data, a dichotomous variable was constructed indicating whether patients had been hospitalized, regardless of the number of admissions.

Psychopathology

Severity of psychopathology was measured with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS).27 Assessors were trained on the PANSS using original training videos to maximize concordance between assessors, which was further facilitated by regular supervised meetings in which videotaped assessments were scored and inconsistencies between assessors discussed.

Cannabis Abuse

Concomitant cannabis misuse was assessed by means of urine analysis at baseline.

Sample Size

We aimed to find a difference on the adherence measures of 0.5 with a SD of 1.0. To achieve a power of 80% of detecting such difference with a medium effect size of 0.5 with a 2-sided significance level of .05, a sample size of 50 patients in each group was needed. With an estimated attrition rate of 20%, we aimed to include 120 patients.

Statistical Analysis

To evaluate the effect of randomization on baseline demographic and disease-specific parameters, t tests were performed for the continuous variables and chi-square tests for the categorical variables. To assess differences in hospitalization rates, chi-square tests were performed, including gender, age, cannabis use, medication administration route, and illness duration as additional grouping variables. For this purpose, the continuous variables age and illness duration were transformed to a dichotomous variable using the median value.

The main effects of interventions on adherence measures were assessed using 1-way between-groups ANOVA, using the baseline values as covariates to adjust for preintervention scores. To assess the influence of age, gender, cannabis use, medication administration route, and illness duration on adherence outcomes, these variables were separately entered as a second fixed factor in 2-way between-groups ANOVA.

To evaluate the effect of the interventions on the severity of psychopathology, mixed between-within subjects ANOVA were performed with PANSS scores as dependant variables.

To detect possible differences between subgroups on severity of psychopathology, separate independent sample t tests were performed with the dichotomous subgroups of the variables gender, age, cannabis use, duration of illness, and medication administration route as independent variables and PANSS scores as dependent variables.

Effect sizes of all significant results are expressed in (partial) eta squared, Cohen’s d, or phi coefficient, depending on the analysis.

Because the majority of patients who dropped out of the intervention-refused follow-up assessments or were lost to follow-up, we were unable to perform an intention to treat analysis and decided to perform a per-protocol analysis instead.

Results

Participants

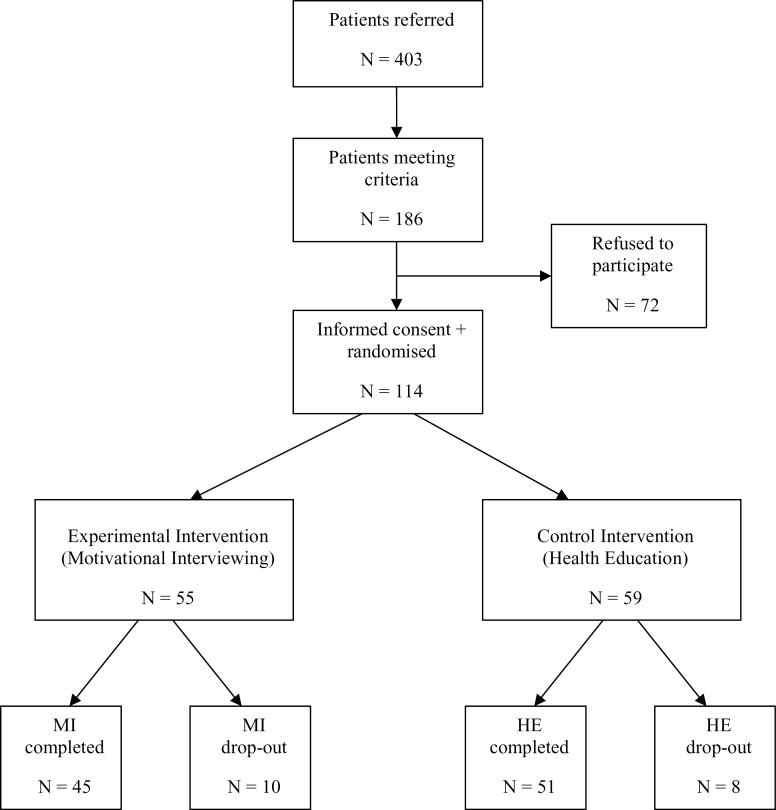

Four hundred and three patients were referred for participation in the study. Of these, 226 did not meet inclusion criteria. Of the 186 remaining patients, 72 refused to participate. One hundred and fourteen patients were randomized and allocated to the two treatment arms. During the intervention, 18 patients dropped out, 10 in the MI group and 8 in the HE group (see figure 1). The group that dropped out was younger (M = 30.7, SD = 11.7) than those who completed interventions (M = 36.8, SD = 9.8; t = −2.35, df = 112, P = .020, Cohen’s d = 0.44) and showed a higher use of cannabis use at trend level (22.2% vs 10.4%; P = .072, φ = 0.22). Nevertheless, these characteristics were equally distributed over both conditions.

Fig. 1.

Consort status.

Demographic characteristics and disease-specific parameters at baseline did not significantly differ between conditions (see table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Total (n = 114) | Motivational Interviewing (n = 55) | Health Education (n = 59) | Pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 35.9 (10.3) | 37 (1.4) | 34.7 (1.4) | .32 |

| Sex: male, n (%) | 91 (80 %) | 43 (78%) | 48 (81%) | .67 |

| Ethnicity: white European, n (%) | 53 (47%) | 26 (47%) | 27 (46%) | .87 |

| Duration of illness, years (SD) | 7.8 (6.4) | 6.8 (5.6) | 8.8 (6.9) | .11 |

| Number of psychiatric admissions, mean (SD) | 3.8 (4.2) | 3.6 (5.3) | 4.0 (3.0) | .71 |

| Diagnosis | .99 | |||

| Schizophrenia, n (%) | 87 (76.3) | 42 (76.4) | 45 (76.3) | |

| Schizoaffective disorder, n (%) | 27 (23.7) | 13 (23.6) | 14 (23.7) | |

| Medication at baseline, n (%) | .48 | |||

| First-generation antipsychotic | 38 (33%) | 17 (31%) | 21 (36%) | |

| Second-generation antipsychotic | 70 (62%) | 36 (65%) | 34 (58%) | |

| Other (mood stabilizer) | 6 (5%) | 2 (4%) | 4 (6%) | |

| Medication administration route, n (%) | .14 | |||

| Oral | 85 (75%) | 44 (80%) | 41 (70%) | |

| Depot | 29 (25%) | 11 (20%) | 18 (30%) | |

| PANSS total, mean (SD) | 71.8 (18.9) | 71.9 (20.9) | 70.2 (15.8) | .64 |

| Cannabis-positive urine sample, n (%) | 14b (24%) | 5 (16%) | 9 (33%) | .11 |

Note: PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale.

aChi-square tests for dichotomous variables; t tests for continuous variables.

bAvailable N = 59.

Interventions

Not all participants received the full 8 sessions of the interventions. The mean number of sessions in the MI group was 6.4 (SD = 1.2) vs 6.6 (SD = 0.9) in the HE group, which was not a significant difference (P = .60).

Adherence

At both follow-up assessments, there were no significant differences between MI and HE on the two adherence measures. Likewise, there were no differences in attitudes toward medication (see table 2).

Table 2.

Effects of Interventions on Adherence Rates

| Motivational Interviewing (n = 30) | Health Education (n = 32) | Pa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| MAQb | |||||

| T0 (baseline) | 3.00 | 1.34 | 3.13 | 1.24 | |

| T1 (posttreatment) | 3.34 | 0.99 | 3.13 | 1.12 | .34 |

| T2 (6-mo follow-up) | 2.97 | 1.42 | 3.38 | 1.11 | .21 |

| DAIc | |||||

| T0 (baseline) | 6.86 | 2.18 | 6.03 | 2.30 | |

| T1 (posttreatment) | 6.64 | 2.50 | 6.38 | 1.98 | .72 |

| T2 (6-mo follow-up) | 6.89 | 2.39 | 6.67 | 2.52 | .70 |

| LCS adherence score by physician and/or caregiverd | |||||

| T0 (baseline) | 4.45 | 0.76 | 4.31 | 0.96 | |

| T1 (posttreatment) | 4.32 | 0.84 | 4.17 | 0.81 | .74 |

| T2 (6-mo follow-up) | 4.33 | 0.82 | 4.36 | 0.71 | .83 |

Note: aUnivariate analysis with baseline value as covariate.

bMAQ, medication adherence questionnaire, score ranges 0–4.

cDAI, Drug Attitude Inventory, score ranges 0–10.

dLCS, life chart schedule, score ranges 1–5.

Next, we examined the differences between subgroups with regard to the effect of MI and HE on adherence. At T1, there were no significant interactions between any of the covariates and intervention type. At T2, there was a significant interaction between the MAQ score and route of medication administration: F(1,59) = 4.53, P = .037, η2 = 0.07, and the LCS score and route of medication administration: F(1,45) = 7.36, P = .009, η2 = 0.14. These results suggest that patients using depot medication show higher adherence rates at 6 months follow-up on the MAQ and the LCS when they received MI, compared with HE.

Furthermore, there was a trend level interaction between the DAI score and age group: F(1,49) = 3.93, P = .05, η2 = 0.07, suggesting that patients younger than 35 years showed more favorable attitudes toward medication at 6 months follow-up when they received MI, compared with HE.

Hospitalization Rates

As shown in table 3, in both groups, 44% of patients were hospitalized at baseline. At T1 (postintervention), there was a nonsignificant difference between the two groups. At T2 (6 months follow-up), 27% of patients in the MI group were hospitalized vs 40% in the control group (P = .19).

Table 3.

Effects of Interventions on Hospitalization Rates

| MI (Ratio Hospitalized) | HE (Ratio Hospitalized) | χ2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0: baseline (n = 114) | 24/55 (44%) | 26/59 (44%) | 0.002 | .963 |

| T1: posttreatment (n = 94) | 17/45 (38%) | 19/49 (39%) | 0.01 | .921 |

| T2: 6-mo follow-up (n = 93) | 12/45 (27%) | 19/48 (40%) | 1.74 | .187 |

| • Females (n = 19) | 1/11 (9%) | 5/8 (63%) | 6.12 | .041 |

| • Males (n = 74) | 11/34 (32%) | 14/40 (35%) | 0.06 | .810 |

| • Cannabis positive (n = 10) | 0/3 (0%) | 3/7 (43%) | 1.84 | .475 |

| • Cannabis negative (n = 40) | 5/25 (20%) | 8/15 (53%) | 4.75 | .041 |

| • Urine analysis refused (n = 43) | 7/17 (41%) | 8/26 (31%) | 0.49 | .484 |

| • Age ≤35 (n = 43) | 3/21 (14%) | 11/22 (50%) | 6.24 | .012 |

| • Age >35 (n = 50) | 9/24 (38%) | 8/26 (31%) | 0.25 | .616 |

| • Duration of illness ≤6 y (n = 41) | 3/22 (14%) | 8/19 (42%) | 4.21 | .040 |

| • Duration of illness >6 y (n = 52) | 9/23 (39%) | 11/29 (38%) | 0.01 | .930 |

| • Depot antipsychotic (n = 25) | 2/10 (20%) | 7/15 (47%) | 1.32 | .380 |

| • Oral antipsychotic (n = 68) | 10/35 (29%) | 12/33 (36%) | 1.20 | .273 |

Note: HE, health education; MI, motivational interviewing.

Next, we performed analyses concerning specific subgroups. In the group of patients younger than 35 years (n = 43), 14% of patients were hospitalized during the follow-up period in the MI group vs 50% in the control group (χ2 = 6.24, df = 1, P = .012, φ = −0.38). In the group >35 years (n = 50), there were no significant differences between conditions (P = .62).

Nine percent of female patients in the MI condition was hospitalized vs 63% in the control condition (χ2 = 6.12, df = 1, P = .041, φ = −0.57). Among male patients (n = 74), there were no significant differences between conditions (P = .81).

In the group with a negative urine analysis on cannabis use at baseline (n = 40), 20% of patients were hospitalized in the MI condition vs 53% in the control condition (χ2 = 4.75, df = 1, P = .041, φ = −0.35). Among those with a positive test on cannabis (n = 10), no significant differences were found (P = .48), just as in the group of patients (n = 43) that refused urine analysis (P = .48). Among patients with an illness duration shorter than 6 years (n = 41), 14% of patients were hospitalized in the MI condition vs 42% in the control condition (χ2 = 4.21, df = 1, P = .040, φ = −0.33). In the group with a longer illness duration (n = 52), there were no significant differences between conditions (P = .93).

Regarding the route of administration of medication, there were no significant differences between MI and HE on hospitalization rates in the group of patients on oral medication (n = 68, P = .27) nor in the group on depot medication (n = 25, P = .38).

Psychopathology

Total PANSS scores showed no significant interaction between intervention type and time (P = .68). There was a large effect for time, with both groups showing a reduction in severity of psychopathology (F(2,110) = 5.59, P = .005 [partial η2 = 0.09]), but there were no differences between the two interventions (P = .99).

There were also no differences between interventions on PANSS subscales for positive symptoms (P = .83), negative symptoms (P = .52), or general symptoms (P = .87) (see table 4).

Table 4.

Psychopathology Rates Across Interventions

| MI (n = 30) | HE (n = 32) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| PANSS total scorea | ||||

| T0 (baseline) | 72.0 | 17.9 | 72.0 | 17.5 |

| T1 (posttreatment) | 65.6 | 22.0 | 63.5 | 16.9 |

| T2 (6-mo follow-up) | 64.0 | 30.3 | 66.2 | 16.7 |

| PANSS-positive symptomsb | ||||

| T0 (baseline) | 16.2 | 5.87 | 17.2 | 6.69 |

| T1 (posttreatment) | 15.2 | 6.29 | 15.0 | 6.05 |

| T2 (6-mo follow-up) | 15.7 | 8.84 | 15.9 | 6.32 |

| PANSS-negative symptomsc | ||||

| T0 (baseline) | 18.7 | 5.80 | 19.1 | 6.56 |

| T1 (posttreatment) | 16.0 | 5.83 | 16.4 | 6.53 |

| T2 (6-mo follow-up) | 16.2 | 7.31 | 17.3 | 6.66 |

| PANSS general symptomsd | ||||

| T0 (baseline) | 37.7 | 9.74 | 35.8 | 8.28 |

| T1 (posttreatment) | 35.4 | 12.98 | 32.2 | 7.07 |

| T2 (6-mo follow-up) | 32.1 | 14.33 | 32.2 | 7.89 |

Focusing on potential treatment effects in terms of symptoms for specific subgroups, female patients showed a larger decrease in general PANSS symptoms in the MI group (Δ 7.9, SD = 4.0) compared with the HE group (Δ 3.4, SD = 2.4); t (11) = −2.40, P = .035. For the other variables, there were no significant effects on changes in PANSS scores.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the effect of an adapted form of MI on medication adherence in patients with multi-episode schizophrenia that were unstable due to medication nonadherence. Regarding adherence and hospitalization rates, we did not find significant differences in adherence over time between MI and HE.

As previous studies incorporating MI in their intervention have shown mixed results,14–19 we hypothesized that the heterogeneity of the investigated patient groups might have been of influence. In addition, we therefore investigated whether specific subgroups of patients (differing on cannabis use, age, illness duration, gender, route of medication administration) may benefit more from MI than others.

Besides a small difference in adherence rates favoring MI over HE in the group who used depot medication on the MAQ and the LCS, no other mediators of treatment effects in terms of medication adherence were found.

However, we did find favorable effects of MI with regard to hospitalization rates. While cannabis use is strongly associated with nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia,1,28 in our study, MI produced significant lower hospitalization rates for the group who does not use cannabis, compared with HE. This may imply that MI is more suitable for improving adherence in patients who do not use cannabis, and that for patients using cannabis specific additional interventions are warranted. MI itself may be of value in this respect, because it has shown efficacy in the treatment of substance abuse, including cannabis abuse.11,29,30

Also, hospitalization rates in the MI condition were found to be lower for patients younger than the median age of 35 years and patients with shorter illness duration. A younger age and a shorter duration of illness are strong risk factors for medication nonadherence.1 Probably related to this, we found that the group who dropped out were aged younger, but this difference was equally distributed over the 2 interventions. This may imply that although nonadherence in the older group was less prevalent, it may have been more persistent and less susceptible for MI. On the other hand, while in the younger group nonadherence was more prevalent, it may also have been more amendable, suggesting MI to be a suitable tool for improving adherence for younger patients who can be engaged in treatment. The fact that there were gender-specific treatment effects of MI resulting in reduced hospitalization rates in female patients is surprising. In most observational studies, gender is not found to be a risk factor for nonadherence.1,31 Female patients with schizophrenia generally show a more favorable course of illness, probably due to the fact that there is a later onset of illness and they show less severe negative and residual symptoms.32 Nevertheless, we have found no correlations with severity of psychopathology and illness duration between the female responders and nonresponders. Although none of the female patients in our study used cannabis and there is less cannabis abuse in female patients with schizophrenia in general,33 the gender difference in the effectiveness of MI on hospitalization rates cannot be explained by cannabis as a confounder, because in the male non-cannabis users, no differences between interventions were found.

As hospitalization rates do not reveal the total time spent in hospital, we compared our results with the duration of hospitalization between interventions, which showed virtually the same differences between the subgroups of patients (see online supplementary material). This is an important outcome, because the time spent in hospital interferes social functioning and hospitalization is associated with increased costs.2

The fact that we found differences in subgroups on hospitalization rates, but not in adherence measures, is remarkable because adherence is strongly associated with relapse rates.3 A possible explanation for this finding may be that there actually was an improvement in adherence, but that measures used in this study are not reliable or sensitive enough. In our study, adherence and attitudes toward medication were measured using the MAQ and the DAI, which both rely on subjective information of patients, and the LCS, of which we used information on adherence by the caregiver and/or a relative. This means that we have used multiple instruments and did not only rely on the patient as the sole information source. However, several authors suggest that all subjective reports concerning medication adherence are considered to be relatively unreliable for determining adherence.6,34 Nevertheless, the information obtained from the professional caregiver in the LCS data in the subgroup of patients on depot medication can be regarded as an exception to this. Therefore, our finding that patients on depot medication show higher adherence rates as assessed with the LCS when they received MI compared with HE, is thought to be reliable. Other measures that may provide more reliable information on adherence are, eg, the level of medication in blood samples or medication-monitoring devices. However, the latter is expensive and the use of invasive measures may negatively influence the willingness of patients to participate in research. Because the focus of our study was to include the most troublesome patients we realized that the willingness to participate would be problematic, so we decided that extra barriers to inclusion were to be avoided. Another problem with the adherence measures in our study is that a ceiling effect of the LCS and the MAQ might have been operating. Therefore, hospitalization may be regarded as a more reliable and valid outcome measure to assess medication adherence in this population. On the other hand, it cannot be ruled out that the observed reduction in hospitalization rates is caused by other factors than medication adherence alone.

In our study, psychopathology rates improved for both groups over time, but there were almost no differences between MI and HE, even when subgroups were analyzed. Although this may appear incongruent with the differences found in hospitalization rates, this is consistent with other studies on adherence interventions, which did not find changes in psychopathology even though improvements in medication adherence or hospitalization rates were found.15,19,35 A possible explanation for these observations might be that MI promotes a nonjudgemental attitude of caregiver toward the beliefs and actions of a patient with regard to medication use. This may result in a more open and trustful relation between the patient and the caregiver, allowing for a better judgement for additional support of the needs for functioning in society, preventing rehospitalization.

Strengths and Limitations

Limitations of the present study are that subgroups were relatively small and patients were not randomized on these characteristics. Therefore, findings concerning subgroups are preliminary and require confirmation in a future randomized controlled trial.

Secondly, both MI and HE were performed by therapists who were not otherwise involved in the treatment of patients, to ensure treatment integrity of the interventions. This choice for external therapists renders uncertainty whether in the meantime during the study period, the treating caregiver(s) might have conducted other interventions or therapeutic styles and to which extend this may have influenced the results.

Thirdly, in our analyses no corrections were applied for multiple comparisons. Although often the Bonferroni method is applied, others have argued that the report of effect sizes in addition to significance levels may provide sufficient information for a correct interpretation of the results.36

Fourthly, the proportion of patients that refused to participate is high (39% of the identified sample), but is almost the same as in comparable studies.17,19 This high refusal rate (partly) reflects the challenging nature of the population, consisting of unstable patients with often poor insight, who had recently been nonadherent. These factors may result in a considerable reluctance to cooperate with a research trial.

Finally, the dropout rate during the interventions (18% in the MI group and 14% in the control group) was considerable, although not unexpected given the severity of the disorder in the included patients. Also there were some patients lost to follow-up, resulting in diminished power. Nevertheless, the attrition rates did not differ between groups, so this will not likely have influenced the results. However, because of the limited power due to a relatively small sample size, clinical relevant effects may have been left undetected. This may especially apply to the considerable difference in hospitalization rate in favor of the MI condition (27% vs 40%).

Strength of this study is that it was designed to include those patients most in need for improvement of adherence. These troublesome patients are often unwilling to participate37 or excluded from studies, because of the chronicity of their illness or concomitant drug abuse. Furthermore, the control group received an active intervention (HE), thereby ensuring that the effects are not influenced by the amount of attention that was given in the intervention condition. Another strength is that we used both subjective (adherence scores) and objective (hospitalization) outcome measures, the latter representing a reliable and valid measure of outcome.

Moreover, we were able to identify possible characteristics of patients for whom MI may be a suitable intervention to improve adherence.

In conclusion, this study shows that an adapted form of MI does not produce a significant effect on medication adherence or hospitalization, compared with HE in a group of nonadherent patients with multi-episode schizophrenia. However, the results provide indications that MI may yet be suitable for improving adherence in female patients, non-cannabis users, younger patients, and those with shorter illness duration. Therefore, targeted use of MI may be of benefit for improving medication adherence in certain groups of patients, although this needs further examination. Furthermore, our findings underscore the need to focus on specific targets that lead to nonadherence and to apply an individualized approach for each patient of this challenging group.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at http://schizophre niabulletin.oxfordjournals.org.

Funding

This work was supported by an investigator-initiated and nonrestricted grant by the Dr. Paul Janssen Foundation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participating patients and staff at the Department of Psychiatry at the Academic Medical Centre (Amsterdam) and at the mental health institutions InGeest (Amsterdam, Haarlem) and Arkin (Amsterdam), and especially the psychologists and community mental health nurses who contributed to the interventions and assessments: Rinske Schepers, Frank van der Horst, Dick Bloemzaad, Anja Lek, Carolien Zeylmaker, and Ronald van Gool. The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

References

- 1. Lacro JP, Dunn LB, Dolder CR, Leckband SG, Jeste DV. Prevalence of and risk factors for medication nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia: a comprehensive review of recent literature. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:892–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Weiden PJ, Olfson M. Cost of relapse in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1995;21:419–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Robinson D, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, et al. Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:241–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Heeg B, Buskens E, Knapp M, et al. Modelling the treated course of schizophrenia: development of a discrete event simulation model. Pharmacoeconomics. 2005;23(s uppl 1):17–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barkhof E, Meijer CJ, de Sonneville LM, Linszen DH, de Haan L. Interventions to improve adherence to antipsychotic medication in patients with schizophrenia–a review of the past decade. Eur Psychiatry. 2012;27:9–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, et al. Expert Consensus Panel on Adherence Problems in Serious and Persistent Mental Illness The expert consensus guideline series: adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(suppl 4):1–46; quiz 47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bien TH, Miller WR, Tonigan JS. Brief interventions for alcohol problems: a review. Addiction. 1993;88:315–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Noonan WC, Moyers TB. Motivational interviewing: a review. J Subst Misuse. 1997;2:8–16 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Harland J, White M, Drinkwater C, Chinn D, Farr L, Howel D. The Newcastle exercise project: a randomised controlled trial of methods to promote physical activity in primary care. BMJ. 1999;319:828–832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Burke BL, Arkowitz H, Menchola M. The efficacy of motivational interviewing: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:843–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lundahl B, Burke BL. The effectiveness and applicability of motivational interviewing: a practice-friendly review of four meta-analyses. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65:1232–1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Barkhof E, de Haan L, Meijer CJ, et al. Motivational interviewing in psychotic disorders. Curr Psychiatr Rev. 2006;2:207–213 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kemp R, Hayward P, Applewhaite G, Everitt B, David A. Compliance therapy in psychotic patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1996;312:345–349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kemp R, Kirov G, Everitt B, Hayward P, David A. Randomised controlled trial of compliance therapy. 18-month follow-up. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172:413–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. O’Donnell C, Donohoe G, Sharkey L, et al. Compliance therapy: a randomised controlled trial in schizophrenia. BMJ. 2003;327:834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gray R, Leese M, Bindman J, et al. Adherence therapy for people with schizophrenia. European multicentre randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189:508–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Maneesakorn S, Robson D, Gournay K, Gray R. An RCT of adherence therapy for people with schizophrenia in Chiang Mai, Thailand. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16:1302–1312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Staring AB, Van der Gaag M, Koopmans GT, et al. Treatment adherence therapy in people with psychotic disorders: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197:448–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Leucht S, Heres S. Epidemiology, clinical consequences, and psychosocial treatment of nonadherence in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(suppl 5):3–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. New York, NY: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health, Education and Welfare Publication (ADM), National Institute of Mental Health; 1976:76–338 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chisholm D, Knapp MR, Knudsen HC, Amaddeo F, Gaite L, van Wijngaarden B. Client Socio-Demographic and Service Receipt Inventory - European Version: development of an instrument for international research. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2000;177:s28–s33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care. 1986;24:67–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Susser E, Finnerty M, Mojtabai R, et al. Reliability of the life chart schedule for assessment of the long-term course of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2000;42:67–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hogan TP, Awad AG, Eastwood R. A self-report scale predictive of drug compliance in schizophrenics: reliability and discriminative validity. Psychol Med. 1983;13:177–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kashner TM, Rader LE, Rodell DE, Beck CM, Rodell LR, Muller K. Family characteristics, substance abuse, and hospitalization patterns of patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 1991;42:195–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hettema J, Steele J, Miller WR. Motivational interviewing. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:91–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Smeerdijk M, Keet R, Dekker N, et al. Motivational interviewing and interaction skills training for parents to change cannabis use in young adults with recent-onset schizophrenia: a randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2012;42:1627–1636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fenton WS, Blyler CR, Heinssen RK. Determinants of medication compliance in schizophrenia: empirical and clinical findings. Schizophr Bull. 1997;23:637–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ochoa S, Usall J, Cobo J, Labad X, Kulkarni J. Gender differences in schizophrenia and first-episode psychosis: a comprehensive literature review. Schizophr Res Treatment. 2012;2012:916198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Foti DJ, Kotov R, Guey LT, Bromet EJ. Cannabis use and the course of schizophrenia: 10-year follow-up after first hospitalization. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:987–993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kikkert MJ, Barbui C, Koeter MW, et al. Assessment of medication adherence in patients with schizophrenia: the Achilles heel of adherence research. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2008;196:274–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Valenstein M, Kavanagh J, Lee T, et al. Using a pharmacy-based intervention to improve antipsychotic adherence among patients with serious mental illness. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:727–736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Perneger TV. What’s wrong with Bonferroni adjustments. BMJ. 1998;316:1236–1238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Storosum J, van Zwieten B, de Haan L. Informed consent from behaviourally disturbed patients. Lancet. 2002;359:83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.