Abstract

Objective

To determine whether outcome disparities between black and white trauma patients have decreased over the last 10 years.

Data Source

Pennsylvania Trauma Outcome Study.

Study Design

We performed an observational cohort study on 191,887 patients admitted to 28 Level 1 and Level II trauma centers. The main outcomes of interest were (1) death, (2) death or major complication, and (3) failure-to-rescue. Hospitals were categorized according to the proportion of black patients. Multivariate regression models were used to estimate trends in racial disparities and to assess whether the source of racial disparities was within or between hospitals.

Principal Findings

Trauma patients admitted to hospitals with high concentrations of blacks (>20 percent) had a 45 percent higher odds of death (adj OR: 1.45, 95 percent CI: 1.09–1.92) and a 73 percent higher odds of death or major complication (adj OR: 1.73, 95 percent CI: 1.42–2.11) compared with patients admitted to hospitals treating low proportions of blacks. Blacks and whites admitted to the same hospitals had no difference in mortality (adj OR: 1.05, 95 percent CI: 0.87, 1.27) or death or major complications (adj OR: 1.01; 95 percent CI: 0.90, 1.13). The odds of overall mortality, and death or major complications have been reduced by 32 percent (adj OR: 0.68; 95 percent CI: 0.54–0.86) and 28 percent (adj OR: 0.72; 95 percent CI: 0.60–0.85) between 2000 and 2009, respectively. Racial disparities did not change over 10 years.

Conclusion

Despite the overall improvement in outcomes, the gap in quality of care between black and white trauma patients in Pennsylvania has not narrowed over the last 10 years. Racial disparities in trauma are due to the fact that black patients are more likely to be treated in lower quality hospitals compared with whites.

Keywords: Race, disparities, trauma

Ethnic and racial disparities in health care quality are widespread and have been extensively documented. The age-adjusted mortality rate for black men is 19 percent higher than for white men (Gornick et al. 1996). Blacks are less likely to receive recommended care for acute myocardial infarctions (Cohen et al. 2010); pneumonia (Hausmann et al. 2009); hip fractures (Neuman et al. 2010); and colorectal, breast, lung, or prostate cancer (Gross et al. 2008). As compared with whites, blacks are two-to-three times more likely to undergo bilateral orchiectomies and lower limb amputations due to suboptimal management of chronic diseases (Gornick et al. 1996). Black patients have a 20 percent higher risk of death after a major surgery compared with whites (Lucas et al. 1996). Eliminating disparities is a national priority and is one of the centerpieces of efforts to improve the health of the U.S. population. Yet, despite decades of efforts to reduce racial disparities, there is very little evidence to suggest that the gap in quality of care between blacks and whites is narrowing (Levine et al. 2001; Voelker 2008, 2010).

One of the leading causes of mortality in the black population is trauma (Gulaid, Onwuachi-Saunders, and Sacks 1984). The life expectancy for blacks is 6 years less than for whites, and trauma contributes almost as much to this disparity in outcomes as ischemic heart disease, stroke, and cancer combined (Wong et al. 2002). Previous studies have demonstrated that blacks are more likely to die after major trauma even after controlling for payer status (Haider et al. 2008, 2012; Crompton et al. 2010; Maybury et al. 2010). Recent work by Haider et al. (2008) has shown that black–white disparities in trauma mortality may result from the fact that hospitals treating higher proportions of minority patients have worse outcomes compared with hospitals treating predominantly white patients. What remains unknown is whether racial disparities also extend to major complications and failure-to-rescue (death after a major complication) (Silber et al. 1992). As major complications are one of the most important determinants of long-term survival in surgical patients (Khuri et al. 2005), understanding black–white differences in complication outcomes is important for understanding the role of racial disparities after trauma patients are discharged home. It is also unknown whether national efforts to reduce overall disparities in health care outcomes have succeeded in reducing racial disparities in trauma.

In this study, we examine mortality and complication trends in Pennsylvania Level I and Level II trauma centers over a 10-year period between 2000 and 2009. Our primary goal was to quantify the outcome disparity between black and white trauma patients, and to determine whether the size of this disparity has changed over the last 10 years. We were also interested in the source of disparities in care. In particular, we wished to determine whether the inferior survival rates and higher complication rates that black trauma patients experience was the result of which trauma center cared for them or was the result of different standards of care for blacks and whites within the same institution.

Methods

Data

This study was conducted using data from the Pennsylvania Trauma Outcome Study (PTOS) on patients admitted to Pennsylvania trauma centers between 2000 and 2009. The Pennsylvania population is representative of injured patients nationally (Mohan et al. 2011). The PTOS database is a population-based statewide trauma registry that includes data on all patients admitted with traumatic injuries to accredited trauma centers in Pennsylvania meeting one or more of the PTOS inclusion criteria: admission to the Intensive Care Unit or step-down unit, hospital length-of-stay greater than 48 hours, hospital admissions transferred from another hospital, and transfers out to an accredited trauma center (2007). The PTOS database includes de-identified data on patient demographics, Abbreviated Injury Score (AIS) codes and ICD-9-CM codes, mechanism of injury (based on ICD-9-CM Ecodes), comorbidities, physiology information, mechanisms of injury, in-hospital mortality and complications, transfer status, processes-of-care, and encrypted hospital identifiers. PTOS includes encrypted hospital identifiers, but it does not contain information on hospital characteristics and cannot be linked to other databases. Steps to insure data quality in the PTOS registry include the use of standard abstraction software with automatic data checks, a data definition manual, and internal and external data auditing (Rogers et al. 2011).

The analysis was limited to trauma patients with age greater than 16, excluding patients with burns, hypothermia, isolated hip fractures, superficial injuries, unspecified injuries, and nontraumatic mechanism of injury admitted to either Level I or Level II trauma centers. From this initial cohort of 226,283 patient observations, we excluded patients with missing information on transfer status (286), demographics (170); invalid AIS codes (12,662), race (15,515); and patients transferred out (4,012). We limited the analysis to black and white patients and excluded 1,751 Asian patients. (The race variable designated patients as either white, black, or Asian.) The study cohort consisted of 191,887 patients admitted to 28 Level 1 or Level II trauma centers. This study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Rochester School of Medicine.

Analysis

The main outcomes were (1) in-hospital death, (2) in-hospital death or major complication, and (3) failure-to-rescue. We defined this composite complication outcome if any of the following occurred after hospital admission: death, ARDS, acute myocardial infarction, acute respiratory failure requiring more than 48 hours of ventilatory support after a period of normal nonassisted breathing (minimum of 48 hours) or reintubation, aspiration pneumonia, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, fat embolism syndrome, acute renal failure, central nervous system infection, progression of original neurologic insult, liver failure, sepsis, septicemia, empyema, dehiscence, gastrointestinal bleeding, small bowel obstruction, compartment syndrome, arterial occlusion, and postoperative hemorrhage. We used death or major complication as a composite outcome, as opposed to complication alone, because it is possible that low-quality care could result in high death rates and paradoxically low complication rates.

The unit of analysis was the patient. The independent variable was race (black vs. white). Trauma centers were stratified into quartiles based on the proportion of black trauma patients they treated: low (≤3.0 percent), medium (3.1–5.5 percent), medium-high (5.6–20.0 percent), and high (> 20 percent).

In our baseline model, we first estimated the independent effect of race on in-hospital death. We used the previously validated Trauma Mortality Prediction Model (TMPM-AIS) (Osler et al. 2008), modified by the addition of age, gender, comorbidities, mechanism of injury (based on Ecodes), transfer status, the GCS motor component, and systolic blood pressure, to control for confounding. Backward stepwise selection was used to select comorbidities. Fractional polynomial analysis was used to determine the optimal specification for continuous predictor variables (Royston and Altman 1994). To estimate the “within hospital” outcome disparity, we modified the baseline model by including hospital indicator variables as fixed effects. This fixed-effect model controls for patient and hospital-level confounders, so that the estimated race effect reflects the extent to which blacks and whites have different outcomes within the same hospital. We performed stratified analyzes after dividing patients into two groups based on injury severity (Baker et al. 1974): (1) mild-to-moderate injury severity (Injury Severity Score [ISS] <15); and (2) severe injury (ISS ≥15). To examine the effect of hospital choice on disparities, we re-estimated the baseline model which was modified to include the hospital proportion of black patients as a hospital-level factor. We then examined the interaction between hospital concentration of black patients and patient race by adding an interaction between hospital strata and race. We performed sensitivity analyzes in which we excluded patients transferred in from other hospital and patients who may have been dead-on-arrival (DOA). As there is no field to identify DOA patients in PTOS, we defined DOA as expired patients with short ED length of stays (<30 minutes) with a blood pressure of zero on admission to the emergency department. We also examined the impact of adding an indicator variable for trauma center status. The results of the sensitivity analyzes were similar to the primary analyzes and are not presented here.

Finally, to further clarify the association between hospital quality and the hospital proportion of black trauma patients, we re-estimated the modified TMPM-AIS using hospital random-effects. This model did not include race as a predictor variable. The empirical-Bayes estimate of the hospital effect was exponentiated to obtain the adjusted mortality odds ratio for each hospital (Glance et al. 2010). Hospitals with an adjusted odds ratio greater than 1 and whose 95 percent confidence interval did not include 1 were classified as low-quality outliers, whereas hospitals with adjusted odds ratios significantly less than 1 were classified as high-quality outliers. Caterpillar graphs were constructed to depict hospital quality as a function of hospital strata.

We then examined the time trend in the black–white difference in mortality by including year as a fixed effect in the baseline model, using the parameterization described by DeLong et al. (1997). To flexibly specify the year-race interaction, we used separate terms for the time variable for whites and for blacks. We tested the significance of the race-year interaction using a model in which year was specified as a continuous variable. Robust variance estimators were used due to the clustering of observations within hospitals (White 1980). The performance of TMPM-AIS was examined using measures of discrimination (C statistic) and calibration (calibration curves).

Analyzes were repeated using (1) the composite outcome of death or major complication, and (2) failure-to-rescue as the outcome of interest. The STATA implementation of the MICE method of multiple imputation described by van Buuren was used to impute missing values of the motor component of the GCS and the systolic blood pressure (van Buuren, Boshuizen, and Knook 1999). Model parameters estimated in the five imputed data sets were combined using Rubin's rule (Rubin 1987). Data management and statistical analyzes were performed using STATA SE/MP Version 11.1 (STATA Corp., College Station, TX, USA). All statistical tests were two-tailed and p values less than .05 were considered significant.

Results

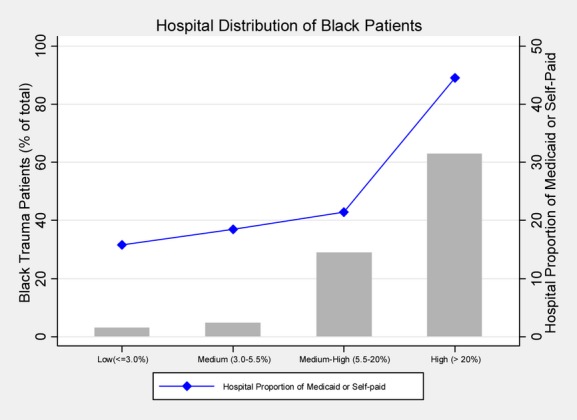

The study sample consisted of 191,887 patients admitted to 28 Level 1 or Level II trauma centers, of which 15.9 percent were black patients. Black patients were younger (36 vs. 51) and more likely to be males (75 percent vs. 60 percent) compared with white patients. Fewer black trauma patients were transferred in (15 percent) compared to white patients (29 percent). A greater number of blacks were admitted with GCS motor scores of 1 (10 percent vs. 7.4 percent) and with systolic blood pressure between 0 and 30 mm Hg (4.9 percent vs. 0.9 percent). More blacks were admitted with gunshot wounds (27 percent vs. 1.8 percent) and stab wounds (8.0 percent vs. 2.7 percent), whereas more white patients were admitted after blunt trauma (43 percent vs. 33 percent) and motor vehicle accidents (28 percent vs. 16 percent) (Table 1). Black patients had higher unadjusted mortality rates compared with whites (9.4 percent vs. 5.8 percent). Sixty-three percent of the black patients were treated in the hospital quartile with the highest proportion of minority patients (Figure 1). Forty-four percent of the trauma patients in hospitals with the highest proportion of black trauma patients were either self-paid or covered by Medicaid versus 16 percent in the hospitals with the lowest proportion of black patients (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Black (n = 30,458) | White (n = 161,429) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, years (median, IQR) | 36 (24, 50) | 51 (33, 74) | <.001 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 22,943 (75.3) | 96,374 (59.7) | <.001 |

| Female | 7,515 (24.7) | 65,055 (40.3) | |

| Transfer from other hospital | |||

| Transferred in | 4,512 (14.8) | 46,594 (28.9) | <.001 |

| Not transferred in | 25,946 (85.2) | 114,835 (71.1) | |

| Glasgow coma scale motor | |||

| GCS motor = 1 | 3,108 (10.2) | 11,926 (7.4) | <.001 |

| GCS motor = 2 | 69 (0.2) | 408 (0.3) | |

| GCS motor = 3 | 113 (0.4) | 558 (0.4) | |

| GCS motor = 4 | 481 (1.6) | 1,842 (1.1) | |

| GCS motor = 5 | 975 (3.2) | 4,254 (2.6) | |

| GCS motor = 6 | 23,826 (78.2) | 131,079 (81.2) | |

| Missing | 1,886 (6.2) | 11,362 (7.0) | |

| Systolic blood pressure | |||

| 0–30 | 1,483 (4.9) | 1,412 (0.9) | <.001 |

| 31–60 | 182 (0.6) | 426 (0.3) | |

| 61–90 | 1,215 (4.0) | 3,895 (2.4) | |

| 91–160 | 22,043 (72.4) | 121,694 (75.4) | |

| 161–220 | 4,509(14.8) | 29,705 (18.4) | |

| >220 | 175 (0.6) | 1,043 (0.7) | |

| Missing | 851 (2.8) | 3,254 (2.0) | |

| Mechanism of trauma | |||

| Blunt | 10,098 (33.2) | 69,529 (43.1) | <.001 |

| Motor vehicle accident | 4,885 (16.0) | 45,581 (28.2) | |

| Gunshot | 8,269 (27.2) | 2,913 (1.8) | |

| Stab | 2,432 (8.0) | 4,307 (2.7) | |

| Pedestrian trauma | 2,604 (8.6) | 14,007 (8.7) | |

| Low-fall | 2,170 (7.1) | 25,092 (15.5) | |

| Mortality | 2,875 (9.4) | 9,401 (5.8) | <.001 |

| Death or major complication | 4,934 (16.2) | 18,917 (11.7) | <.001 |

GCS motor, motor component of the Glasgow coma scale; IQR, interquartile range.

Figure 1.

Distribution of Black Trauma Patients and Hospital Proportion of Poorly Insured Trauma Patients as a Function of the Hospital Proportion of Black Patients

After adjusting for clinical factors, black patients had significantly higher mortality (adjusted OR [AOR]: 1.21, 95 percent CI: 1.08–1.36, p < .002) and death or major complication (AOR: 1.28, 95 percent CI: 1.11–1.47, p < .001), and failure-to-rescue (AOR: 1.24; 95 percent CI: 1.09–1.40, p = .001). Controlling for clinical factors and hospital effects, black–white differences in (1) mortality rates (AOR: 1.05, 95 percent CI: 0.87–1.26, p = .622), (2) death or major complication (AOR: 1.01, 95 percent CI: 0.90–1.13, p = .872), and (3) failure-to-rescue (AOR: 1.08, 95 percent CI: 0.93–1.25, p = .322) disappeared (Table 2). In our stratified analyzes, we found that black–white disparities were only evident in patients with severe injuries (ISS ≥15) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Risk-Adjusted Trauma Outcomes as a Function of Race (Adjusted OR for Black–White Comparison with White Patients as the Reference Group)

| Unadjusted | Overall* | Within Hospitals† | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Mortality | ||||||

| Injury severity | ||||||

| All patients | 1.69 (1.39–2.04) | <.001 | 1.21 (1.08–1.36) | .002 | 1.05 (0.87–1.26) | .622 |

| ISS <15 | 1.82 (1.23–2.70) | <.001 | 1.14 (0.88–1.47) | .325 | 0.95 (0.69–1.31) | .751 |

| ISS ≥15 | 1.95 (1.70–2.22) | <.001 | 1.23 (1.10–1.37) | <.001 | 1.09 (0.92–1.28) | .340 |

| Death or major complication | ||||||

| Injury severity | ||||||

| All patients | 1.46 (1.19–1.78) | <.001 | 1.28 (1.11–1.47) | <.001 | 1.01 (0.90–1.13) | .872 |

| ISS <15 | 1.43 (1.07–1.92) | .017 | 1.19 (0.96–1.46) | .111 | 0.92 (0.79–1.07) | .259 |

| ISS ≥15 | 1.78 (1.52–2.08) | <.001 | 1.35 (1.21–1.51) | <.001 | 1.08 (0.97–1.20) | .168 |

| Failure-to-rescue | ||||||

| Injury severity | ||||||

| All patients | 0.77 (0.63, 0.95) | .012 | 1.24 (1.09, 1.40) | .001 | 1.08 (0.93, 1.25) | .322 |

| ISS <15 | 0.46 (0.31–0.68) | <.001 | 1.00 (0.71–1.41) | .990 | 0.90 (0.59–1.37) | .627 |

| ISS ≥15 | 0.89 (0.73–1.07) | .209 | 1.32 (1.16–1.50) | <.001 | 1.12 (0.92–1.38) | .253 |

ISS, injury severity score; OR, odds ratio.

Indicates patient-level risk adjustment model (age, sex, transfer status, injury severity, mechanism of injury, motor component of Glasgow coma scale, systolic blood pressure, comorbidities, year of admission).

Indicates within-hospital risk adjustment model using hospital fixed-effects model (all patient risk factors above plus hospital fixed effects).

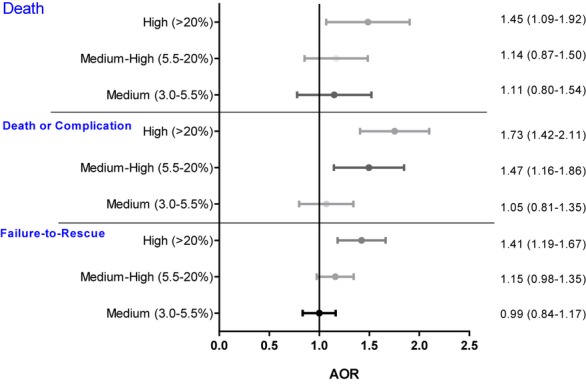

Patients admitted to hospitals with high concentrations of black trauma patients (>20 percent) had 45 percent higher odds of mortality compared to patients admitted to hospitals treating low concentrations of blacks (AOR: 1.45, 95 percent CI: 1.09–1.92, p = .01) (Figure 2). Blacks and whites admitted to hospitals with high concentrations of black patients had similar mortality (p = .422) (Table 3). Outcomes for black and white patients admitted to trauma centers with medium or medium-high concentrations of black patients were not significantly different than outcomes for white patients admitted to trauma centers with low concentrations of black patients (reference population) (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Outcomes as a Function of Hospital Concentration of Black Patients, after Adjusting for Age, Sex, Transfer Status, Injury Severity, Mechanism of Injury, Motor Component of Glasgow Coma Scale, Systolic Blood Pressure, Comorbidities, and Year of Admission

Table 3.

Risk-Adjusted Trauma Outcomes versus Hospital Concentration of Black Trauma Patients

| Trauma Centers by Concentration of Black Patients | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (≤3.5%) | Medium (3.6–6.0%) | Medium-High (6.1–20%) | High (>20%) | |||||

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Mortality | ||||||||

| Whites | 1 [Reference] | 1.12 (0.81–1.55) | .497 | 1.16 (0.88–1.52) | .286 | 1.38 (0.97–1.96) | .076 | |

| Blacks | 1.34 (0.94–1.90) | .107 | 1.06 (0.69–1.64) | .783 | 1.05 (0.76–1.46) | .769 | 1.56* (1.19–2.05) | .001 |

| Death or major complication | ||||||||

| Whites | 1 [Reference] | 1.06 (0.81–1.36) | .654 | 1.47 (1.16–1.87) | .002 | 1.65 (1.35–2.03) | <.001 | |

| Blacks | 1.08 (0.91–1.29) | .384 | 0.84 (0.64–1.11) | .228 | 1.47 (1.16–1.88) | .002 | 1.85* (1.46–2.33) | <.001 |

| Failure-to-rescue | ||||||||

| Whites | 1 [Reference] | 1.00 (0.85, 1.17) | .991 | 1.15 (0.99, 1.34) | .074 | 1.40 (1.17, 1.70) | <.001 | |

| Blacks | 1.48 (0.82, 2.68) | .189 | 1.13 (0.43, 2.98) | .809 | 1.30 (0.97, 1.73) | .082 | 1.47* (1.21, 1.78) | <.001 |

Risk adjustment model adjusts for patient level factors (age, sex, transfer status, injury severity, mechanism of injury, motor component of Glasgow coma scale, systolic blood pressure, comorbidities, year of admission), and for interaction between race and hospital concentration of black patients.

Comparison between whites and black patients in trauma centers with high concentrations of black patients is not significant (p > .25).

OR, odds ratio.

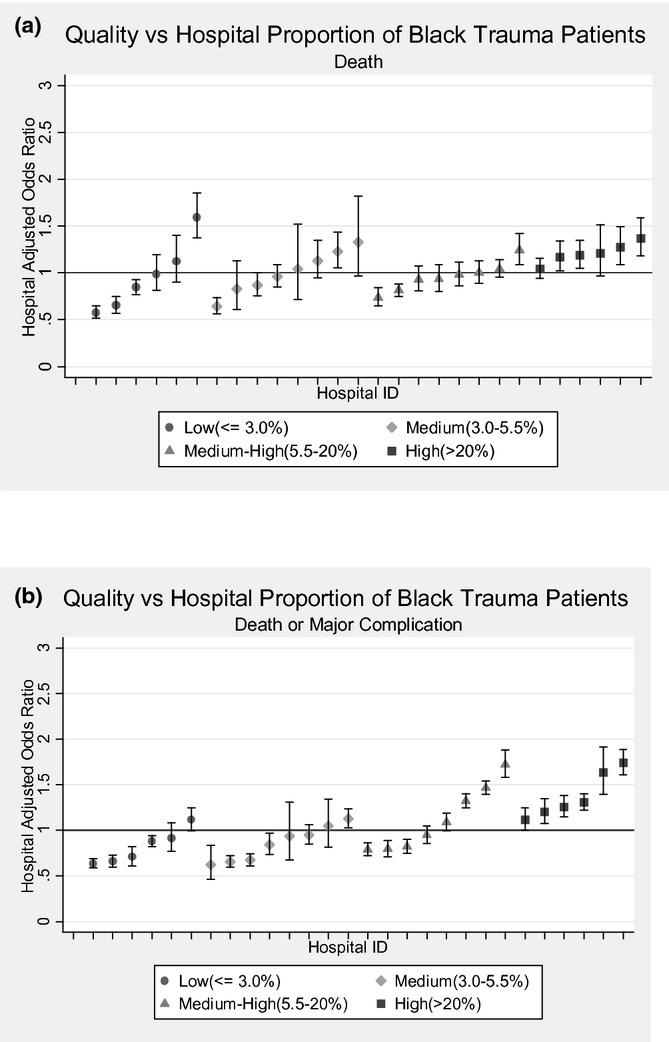

Trauma patients admitted to hospitals with high concentrations of black patients (>20 percent) had approximately 75 percent higher odds of death or major complication compared with patients admitted to hospitals treating low concentrations of blacks (<3 percent) (AOR 1.73, 95 percent CI: 1.47–2.11, p < .001) (Figure 2). There was no significant difference in death or major complication between black and white patients admitted to trauma centers treating high proportions of black patients (p = .289) (Table 3). Similar results were obtained for black and white patients treated at hospitals with medium-high concentrations of black patients (Table 3). Injured patients admitted to black-serving hospitals had a 41 percent higher odds of failure-to-rescue compared to patients admitted to white-serving hospitals (AOR 1.41; 95 percent CI: 1.19–1.67). Figure 3 shows the quality of trauma centers as a function of the hospital strata based on the proportion of minority patients. These graphs confirm that lower quality hospitals tend to treat higher concentrations of black patients.

Figure 3.

(a) Hospital Quality, Based on Death or Major Complications, as a Function of the Minority Patient Population. Each trauma center is represented by a separate point. (b) Hospital Quality, Based on Death or Major Complications, as a Function of the Minority Patient Population. Error bars represent 95 percent confidence intervals. Each trauma center is represented by a separate point

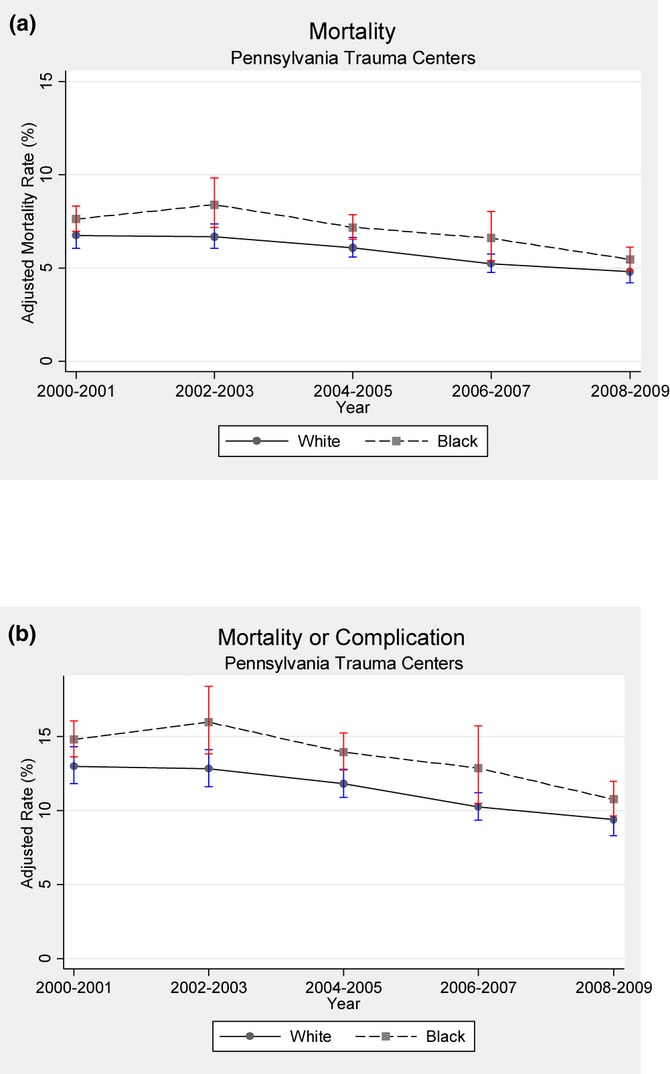

The odds of overall mortality, and death or major complication declined by 32 percent (adj OR 0.68; 95 percent CI: 0.54–0.86; p = .001) and 28 percent (adj OR 0.72; 95 percent CI: 0.60–0.85; p < .001) between 2000 and 2009, respectively. The gap between black and white patients has not changed significantly for mortality over this time period (p = .902). When we tested the interaction between year and race for death or major complication, we found marginally significant evidence that the gap between blacks and whites may have slightly widened over time (adj OR 1.03; 95 percent CI: 1.00–1.05; p = .05) (Figure 4a and b).

Figure 4.

(a) Adjusted Mortality Rate for Black versus White Patients between 2000 and 2009. (The gap between blacks and whites did not change over time [p = .902]. Vertical bars represent 95 percent confidence intervals.) (b) Adjusted Death or Major Complication Rate for Black versus White Patients between 2000 and 2009. (The gap between blacks and whites increases slightly over time [adj OR 1.03; 95 percent CI: 1.00–1.05; p = .05]. Vertical bars represent 95 percent confidence intervals)

The risk-adjustment models used for risk-adjustment for mortality, death or major complication, both exhibited excellent discrimination with C statistics of 0.96 and 0.89, respectively. Both models exhibit excellent calibration (calibration curves are shown in the Appendix).

Comment

Black and white patients treated at Pennsylvania Level I or Level II trauma centers with high concentrations of black trauma patients have a 45 percent higher risk of mortality, nearly 75 percent higher risk of death or major complication, and a 40 percent higher risk of failure-to-rescue. Our results suggest that trauma care is segregated along racial lines, and that trauma centers serving large black populations have significantly worse outcomes compared with trauma centers with few black patients. In effect, the concentration of black patients in trauma centers is a marker for lower quality care. Within the same hospital, blacks and whites have similar outcomes, which suggest that racial bias within hospitals is not an important cause for the observed black–white outcome disparity. While trauma mortality has decreased by 30 percent over the last 10 years, there has been essentially no progress toward narrowing the black–white difference in trauma outcomes over the last decade despite the national focus on reducing disparities in health care.

The wide variability in outcomes for injured patients treated at different hospitals has been labeled the Quality Chasm in Trauma by the American College of Surgeons (ACS) Committee on Trauma (COT) (Shafi et al. 2009). In 2006, the COT launched the Trauma Quality Improvement Program (TQIP), a national benchmarking effort to “measure and improve the quality of trauma care” (Shafi et al. 2009). Recognition of the quality gap in trauma care has been accompanied by increasing evidence of an equity gap. To date, reporting on racial disparities and efforts to reduce black–white differences in trauma outcomes have not been integrated within ACS TQIP. Our findings, in combination with those of Haider et al. (2012), suggest that black–white differences in trauma outcomes occur, because hospitals that serve minority populations tend to have worse outcomes compared with hospitals with fewer minority patients, and not because black patients receive worse care than white patients within the same hospitals. Thus, report cards stratifying trauma outcomes by race may not be necessary if the source of racial disparities is primarily due to the differences in outcomes between hospitals as opposed to within-hospital differences.

Other studies have also shown that patients admitted to hospitals that serve high proportions of black patients are less likely to receive recommended care, and more likely to experience complications and die (Barnato et al. 2005; Skinner et al. 2005; Lucas et al. 2006; Hasnain-Wynia et al. 2007; Jha et al. 2007; Gaskin et al. 2008; Hausmann et al. 2009; Ly et al. 2010; Mayr et al. 2010). Twenty-five percent of hospitals in the United States care for nearly 90 percent of the elderly black population (Jha et al. 2007). Health care is racially segregated and hospitals serving disproportionately high concentrations of minority patients tend to be lower quality institutions (Blustein 2008; Chandra 2009). “Forty years after the passage of [the] Civil Rights Act, minority healthcare is de facto separate and unequal” (Chandra 2009). The organizational capacity to improve health care quality through recruitment and retention of outstanding clinical staff and infrastructure investment is limited in under resourced settings serving minority populations (Blustein 2008). In our study, black-serving hospitals had over twice as many Medicaid or self-paid trauma patients as hospitals serving the fewest black trauma patients. In many states, the viability of trauma care delivery is itself threatened by financial consideration (Mann et al. 2005), further adding to the challenge of improving the quality of under-performing trauma centers. Reducing racial disparities in trauma care may require policies that focus on improving health care quality in hospitals that have the fewest internal resources and the worst performance.

One of the troubling implications of these findings is that current pay-for-performance policies designed to reward higher performing hospitals may end up diverting resources from black-serving hospitals that may be resource-poor, and in the process increase racial disparities rather than reduce them (Blustein 2008). Alternatively, targeting quality improvement resources to hospitals serving large minority populations by paying for improvement may be the most cost-effective way of improving health outcomes in minority populations (Jha et al. 2007). Rewarding incremental performance improvement may be a more effective means of improving the quality of black-serving hospitals than basing incentive payments on measures of absolute performance (Casalino et al. 2007; Ho, Moy, and Clancy 2010; Li et al. 2011). Federal reimbursement policy could also be modified to further increase payments to safety-net hospitals serving a disproportionate number of low-income patients to increase the capacity of these hospitals to commit resources to quality improvement. Recent findings that safety-net hospitals tend to have smaller improvements in performance over time compared to non-safety-net hospitals (Werner, Goldman, and Dudley 2008) challenges policy makers to provide additional resources to hospitals caring for disadvantaged patient populations.

This study has some limitations. First, it is possible that black–white differences in outcomes may be secondary to unobserved heterogeneity in risk factors across racial groups, generating increased disease severity in blacks compared with whites. If so, our findings that black-serving hospitals have worse outcomes could be caused by increased unmeasured injury severity in black patients compared with white patients. Confounding is always a consideration in observational studies, although the excellent statistical performance of our risk adjustment models, and the use of comprehensive clinical as opposed to administrative data, mitigates this concern and makes this unlikely. Second, although our study is population-based, it was conducted using data from Pennsylvania and therefore may not be generalizable to the rest of the United States. Third, 8 percent of our observations had missing values for the physiology data. Missing data are commonly encountered in the registry data. Complete case analysis, which excludes observations with missing data, can lead to biased conclusions. Multiple imputation is widely recognized as the method of choice for handling missing data, and it was used in our analysis (van der Heijden et al. 2006; Harel and Zhou 2007). Fourth, complications are not always consistently coded across hospitals. However, in order for this to introduce bias, we would have to assume that black-serving hospitals are more likely to code complications compared to hospitals with lower proportions of black patients. Finally, because the PTOS data do not identify Hispanic ethnicity, our analysis could not examine outcomes in this important minority group.

Our study has several strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the trend in racial disparities for trauma patients. It is also the first study to examine black–white differences in complications in injured patients. In addition, our use of the hospital proportion of black patients to stratify hospitals on a hospital report card uniquely draws attention to the close association between hospital quality of care and the extent to which hospitals serve black patient populations.

In conclusion, our analysis demonstrates that the gap in quality of care between black and white trauma patients in Pennsylvania has remained constant over the last 10 years. Racial disparities appear to be primarily a function of where black patients are treated, because black and whites have similar outcomes when they are treated within the same hospital. Black patients are more likely to be treated in lower quality trauma centers that treat a disproportionate number of black patients. These findings have important policy implications. Interventions designed to reduce disparities between black and white trauma patients within the same hospital are unlikely to succeed in improving racial equity. Incentive programs that focus on rewarding high-performance hospitals may have the unintended consequence of actually widening the racial gap in the quality of trauma care. Our findings highlight the value of redesigning hospital incentive programs to reward quality improvement in the lowest performance hospitals if the goal is to simultaneously improve overall quality and reduce racial disparities.

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: This project was supported by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (RO1 HS 16737). The views presented in this manuscript are those of the authors and may not reflect those of the Agency for Healthcare and Quality Research. These data were provided by the Pennsylvania Trauma Systems Foundation. The Foundation specifically disclaims responsibility for any analyses, interpretations, or conclusions. All authors have approved the final version of this manuscript.

Disclosures: None.

Disclaimer: None.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Appendix SA2: Calibration Curves for TMPM-AIS for (1) Mortality and (2) Death or Major Complication. (Vertical bars represent 95 percent confidence intervals.)

References

- Baker SP, O'Neill B, Haddon W, Jr, Long WB. “The Injury Severity Score: A Method for Describing Patients with Multiple Injuries and Evaluating Emergency Care”. Journal of Trauma. 1974;14(3):187–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnato AE, Lucas FL, Staiger D, Wennberg DE, Chandra A. “Hospital-Level Racial Disparities in Acute Myocardial Infarction Treatment and Outcomes 2”. Medical Care. 2005;43(4):308–19. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000156848.62086.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blustein J. “Who Is Accountable for Racial Equity in Health Care?”. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;299(7):814–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.7.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Buuren S, Boshuizen HC, Knook DL. “Multiple Imputation of Missing Blood Pressure Covariates in Survival Analysis”. Statistics in Medicine. 1999;18(6):681–94. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<681::aid-sim71>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casalino LP, Elster A, Eisenberg A, Lewis E, Montgomery J, Ramos D. “Will Pay-for-Performance and Quality Reporting Affect Health Care Disparities?”. Health Affairs. 2007;26(3):w405–14. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.w405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra A. “Who You Are and Where You Live: Race and the Geography of Healthcare”. Medical Care. 2009;47(2):135–7. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a4c5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MG, Fonarow GC, Peterson ED, Moscucci M, Dai D, Hernandez AF, Bonow RO, Smith SC., Jr “Racial and Ethnic Differences in the Treatment of Acute Myocardial Infarction: Findings from the Get with the Guidelines-Coronary Artery Disease Program”. Circulation. 2010;121(21):2294–301. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.922286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crompton JG, Pollack KM, Oyetunji T, Chang DC, Efron DT, Haut ER, Cornwell EE, 3rd, Haider AH. “Racial Disparities in Motorcycle-Related Mortality: An Analysis of the National Trauma Data Bank”. American Journal of Surgery. 2010;200(2):191–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLong ER, Peterson ED, DeLong DM, Muhlbaier LH, Hackett S, Mark DB. “Comparing Risk-Adjustment Methods for Provider Profiling”. Statistics in Medicine. 1997;16(23):2645–64. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19971215)16:23<2645::aid-sim696>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaskin DJ, Spencer CS, Richard P, Anderson GF, Powe NR, Laveist TA. “Do Hospitals Provide Lower-Quality Care to Minorities Than to Whites?”. Health Affairs. 2008;27(2):518–27. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glance LG, Dick AW, Mukamel DB, Meredith W, Osler TM. “The Effect of Preexisting Conditions on Hospital Quality Measurement for Injured Patients”. Annals of Surgery. 2010;251(4):728–34. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181d56770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gornick ME, Eggers PW, Reilly TW, Mentnech RM, Fitterman LK, Kucken LE, Vladeck BC. “Effects of Race and Income on Mortality and Use of Services among Medicare Beneficiaries 6”. New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;335(11):791–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199609123351106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross CP, Smith BD, Wolf E, Andersen M. “Racial Disparities in Cancer Therapy: Did the Gap Narrow between 1992 and 2002?”. Cancer. 2008;112(4):900–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulaid JA, Onwuachi-Saunders EC, Sacks JJ. MMWR CDC Surveillance Summary; 1984. Differences in Death Rates due to Injury among Blacks and Whites, 1984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haider AH, Chang DC, Efron DT, Haut ER, Crandall M, Cornwell EE., 3rd “Race and Insurance Status as Risk Factors for Trauma Mortality”. Archives of Surgery. 2008;143(10):945–9. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.10.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haider AH, Ong'uti S, Efron DT, Haut ER, Crandall M, Cornwell EE., 3rd “Association between Hospitals Caring for a Disproportionately High Percentage of Minority Trauma Patients and Increased Mortality: A Nationwide Analysis of 434 Hospitals”. Archives of Surgery. 2012;147(1):63–7. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harel O, Zhou XH. “Multiple Imputation: Review of Theory, Implementation and Software”. Statistics in Medicine. 2007;26(16):3057–77. doi: 10.1002/sim.2787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasnain-Wynia R, Baker DW, Nerenz D, Feinglass J, Beal AC, Landrum MB, Behal R, Weissman JS. “Disparities in Health Care Are Driven by Where Minority Patients Seek Care: Examination of the Hospital Quality Alliance Measures”. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167(12):1233–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.12.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausmann LR, Ibrahim SA, Mehrotra A, Nsa J, Bratzler DW, Mor MK, Fine MJ. “Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Pneumonia Treatment and Mortality”. Medical Care. 2009;47(9):1009–17. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181a80fdc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Heijden GJ, Donders AR, Stijnen T, Moons KG. “Imputation of Missing Values Is Superior to Complete Case Analysis and the Missing-Indicator Method in Multivariable Diagnostic Research: A Clinical Example”. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2006;59(10):1102–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho K, Moy E, Clancy CM. “Can Incentives to Improve Quality Reduce Disparities?”. Health Services Research. 2010;45(1):1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha AK, Orav EJ, Li Z, Epstein AM. “Concentration and Quality of Hospitals That Care for Elderly Black Patients”. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167(11):1177–82. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.11.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khuri SF, Henderson WG, DePalma RG, Mosca C, Healey NA, Kumbhani DJ. “Determinants of Long-Term Survival after Major Surgery and the Adverse Effect of Postoperative Complications”. Annals of Surgery. 2005;242(3):326–41. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000179621.33268.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine RS, Foster JE, Fullilove RE, Fullilove MT, Briggs NC, Hull PC, Husaini BA, Hennekens CH. “Black–white Inequalities in Mortality and Life Expectancy, 1933–1999: Implications for Healthy People 2010”. Public Health Reports. 2001;116(5):474–83. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.5.474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Yin J, Cai X, Temkin-Greener J, Mukamel DB. “Association of Race and Sites of Care with Pressure Ulcers in High-Risk Nursing Home Residents”. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2011;306(2):179–86. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas FL, Stukel TA, Morris AM, Siewers AE, Birkmeyer JD. “Race and Surgical Mortality in the United States”. Annals of Surgery. 2006;243(2):281–6. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000197560.92456.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ly DP, Lopez L, Isaac T, Jha AK. “How Do Black-Serving Hospitals Perform on Patient Safety Indicators? Implications for National Public Reporting and Pay-for-Performance”. Medical Care. 2010;48(12):1133–7. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181f81c7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann NC, MacKenzie E, Teitelbaum SD, Wright D, Anderson C. “Trauma System Structure and Viability in the Current Healthcare Environment: A State-By-State Assessment”. Journal of Trauma. 2005;58(1):136–47. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000151181.44658.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maybury RS, Bolorunduro OB, Villegas C, Haut ER, Stevens K, Cornwell EE, 3rd, Efron DT, Haider AH. “Pedestrians Struck by Motor Vehicles Further Worsen Race- and Insurance-Based Disparities in Trauma Outcomes: The Case for Inner-City Pedestrian Injury Prevention Programs”. Surgery. 2010;148(2):202–8. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayr FB, Yende S, D'Angelo G, Barnato AE, Kellum JA, Weissfeld L, Yealy DM, Reade MC, Milbrandt EB, Angus DC. “Do Hospitals Provide Lower Quality of Care to Black Patients for Pneumonia?”. Critical Care Medicine. 2010;38(3):759–65. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181c8fd58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan D, Rosengart MR, Farris C, Cohen E, Angus DC, Barnato AE. “Assessing the Feasibility of the American College of Surgeons' Benchmarks for the Triage of Trauma Patients”. Archives of Surgery. 2011;146(7):786–92. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuman MD, Fleisher LA, Even-Shoshan O, Mi L, Silber JH. “Nonoperative Care for Hip Fracture in the Elderly: The Influence of Race, Income, and Comorbidities”. Medical Care. 2010;48(4):314–20. doi: 10.1097/mlr.0b013e3181ca4126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osler T, Glance L, Buzas JS, Mukamel D, Wagner J, Dick A. “A Trauma Mortality Prediction Model Based on the Anatomic Injury Scale”. Annals of Surgery. 2008;247(6):1041–8. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31816ffb3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennsylvania Trauma Systems Foundation Annual Report. Mechanicsburg, PA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers FB, Osler T, Lee JC, Sakorafas L, Wu D, Evans T, Edavettal M, Horst M. “In a Mature Trauma System, There Is No Difference in Outcome (Survival) between Level I and Level II Trauma Centers”. Journal of Trauma. 2011;70(6):1354–7. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182183789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royston P, Altman DG. “Regression Using Fractional Polynomials of Continuous Covariates: Parsimonious Parameteric Modeling”. Applied Statistics. 1994;43:429–67. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin D. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Shafi S, Nathens AB, Cryer HG, Hemmila MR, Pasquale MD, Clark DE, Neal M, Goble S, Meredith JW, Fildes JJ. “The Trauma Quality Improvement Program of the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma”. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2009;209(4):521–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.07.001. e521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silber JH, Williams SV, Krakauer H, Schwartz JS. “Hospital and Patient Characteristics Associated with Death after Surgery. A Study of Adverse Occurrence and Failure to Rescue”. Medical Care. 1992;30(7):615–29. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199207000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner J, Chandra A, Staiger D, Lee J, McClellan M. “Mortality after Acute Myocardial Infarction in Hospitals That Disproportionately Treat Black Patients 1”. Circulation. 2005;112(17):2634–41. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.543231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Rockville, MD: Author; 2011. 2010 National Healthcare Quality Report. [Google Scholar]

- Voelker R. “Decades of Work to Reduce Disparities in Health Care Produce Limited Success”. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;299(12):1411–3. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.12.1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner RM, Goldman LE, Dudley RA. “Comparison of Change in Quality of Care between Safety-Net and Non-Safety-Net Hospitals”. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;299(18):2180–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.18.2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White H. “A Heteroskedasticity-Consistent Covariance Matrix Estimator and a Direct Test for Heteroskedasticity”. Econometrica. 1980;48:817–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wong MD, Shapiro MF, Boscardin WJ, Ettner SL. “Contribution of Major Diseases to Disparities in Mortality”. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;347(20):1585–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.