Abstract

Background

Approximately 40 percent of individuals using out-of-network physicians experience involuntary out-of-network care, leading to unexpected and sometimes burdensome financial charges. Despite its prevalence, research on patient experiences with involuntary out-of-network care is limited. Greater understanding of patient experiences may inform policy solutions to address this issue.

Objective

To characterize the experiences of patients who encountered involuntary out-of-network physician charges.

Methods

Qualitative study using 26 in-depth telephone interviews with a semi-structured interview guide. Participants were a purposeful sample of privately insured adults from across the United States who experienced involuntary out-of-network care. They were diverse with regard to income level, education, and health status. Recurrent themes were generated using the constant comparison method of data analysis by a multidisciplinary team.

Results

Four themes characterize the perspective of individuals who experienced involuntary out-of-network physician charges: (1) responsibilities and mechanisms for determining network participation are not transparent; (2) physician procedures for billing and disclosure of physician out-of-network status are inconsistent; (3) serious illness requiring emergency care or hospitalization precludes ability to choose a physician or confirm network participation; and (4) resources for mediation of involuntary charges once they occur are not available.

Conclusions

Our data reveal that patient education may not be sufficient to reduce the prevalence and financial burden of involuntary out-of-network care. Participants described experiencing involuntary out-of-network health care charges due to system-level failures. As policy makers seek solutions, our findings suggest several potential areas of further consideration such as standardization of processes to disclose that a physician is out-of-network, holding patients harmless not only for out-of-network emergency room care but also for non-elective hospitalization, and designation of a mediator for involuntary charges.

Keywords: Qualitative methods, managed care, out-of-network care, health policy

Private health insurance plans with a network of approved physicians are common; in one 2011 survey, 88 percent of privately insured adults aged 18–64 years reported enrollment in a plan with a network (Kyanko, Curry, and Busch, unpublished data). While most patients remain in-network when choosing a physician, out-of-network care is not infrequent. The same survey found that 8 percent of patients who had seen a physician in the prior year had used an out-of-network physician, and an analysis of 2003 claims data estimated that out-of-network care accounted for 10–13 percent of covered expenses (McDevitt et al. 2007; Kyanko, Curry, and Busch 2012). Patients may use in-network physicians at low or no cost, and yet are responsible for higher out-of-pocket costs when using out-of-network physicians, including higher co-payments or co-insurance as well as the “balance bill” or difference between the physician's billed charge (i.e., list price) and insurer reimbursement. There is no available estimate of the average out-of-pocket cost for out-of-network care; however, these bills have the potential to be quite high as some providers’ billed charges can exceed ten to several hundred times the Medicare reimbursement rate (Americas Health Insurance Plans 2013).

Seeking care from an out-of-network physician is intended to be a deliberate choice; however, approximately 40 percent of patients using out-of-network physicians experience unexpected or involuntary out-of-network charges, representing almost 3 million patients annually in the United States (Kyanko, Curry, and Busch 2012). A patient may use an out-of-network physician involuntarily in several scenarios. The insurer's physician directory may be inaccurate or not updated. A patient may not be aware that a physician was out-of-network until receiving the bill; this may be especially problematic for hospital-based physicians such as radiologists or anesthesiologists who are often not chosen by the patient. In an emergency, a patient may not be able to choose an in-network physician, or an in-network physician may not be available (Hoadley, Lucia, and Schwartz 2009; New York State Department of Financial Services 2012; Kyanko, Curry, and Busch 2012; Kyanko and Busch 2013).

The frequency of involuntary out-of-network care and its potential for financial burden have spurred policy interest on both the state and federal levels (Kyanko and Busch 2013). Proposed solutions vary considerably. For example, several states have passed legislation to improve transparency by requiring that physicians disclose out-of-network status prior to delivering services (Texas SB 1731 2007; Louisiana Act No. 354 2009). The Affordable Care Act prohibits increased cost-sharing for out-of-network emergency room services, although it allows for balance billing (Federal Register 2010). Texas requires the availability of a mediator for disputed out-of-network charges (Texas HB 2256 2009).

Despite the growing attention to this issue, research to inform evidence-based policy is limited. A 2012 New York State report surveyed insurers on their policies to prevent involuntary out-of-network charges, finding variation in benchmarks for calculating reimbursement for out-of-network care, available tools for calculating out-of-pocket costs, procedures to prevent use of out-of-network hospital-based physicians, and claims submission processes (New York State Department of Financial Services 2012). Another report interviewed key policy makers in four states on different regulatory approaches to protecting patients from unexpected out-of-network charges (Hoadley, Lucia, and Schwartz 2009). However, the patient experience is not represented through empirical evidence but rather is restricted to anecdotal reports (Raeburn 2009; Andrews 2011; Appleby 2012). Accordingly, we sought to characterize the experiences of patients who encountered involuntary out-of-network physician charges.

Methods

This qualitative study is part of a larger sequential explanatory mixed methods study (Creswell and Clark 2011). Results of the quantitative component have been published previously (Kyanko, Curry, and Busch 2012). Objectives of the explanatory component, using a qualitative approach, were to address unanswered questions from the quantitative component (Creswell and Clark 2011), as well as to generate detailed descriptions of participants’ out-of-network care experiences (Pope and Mays 1995; Bradley, Curry, and Devers 2007).

In-depth telephone interviews (Britten 1995) were conducted in May–June 2011 with adults with private health insurance who had experienced involuntary out-of-network care. Participants were recruited from respondents to the online panel survey on out-of-network experiences administered in February 2011 by KnowledgeNetworks (KnowledgeNetworks 2011), a private survey research firm. Full details of survey methods are available elsewhere (Kyanko, Curry, and Busch 2012). Fifty-two percent (n = 372/721) of survey respondents agreed to be contacted for a telephone interview. Respondents who agreed to be contacted versus those who refused did not differ by demographic characteristics or whether they experienced involuntary out-of-network care or nontransparent costs (Table S1). Of those agreeing to be contacted, 34 percent (n = 125/372) experienced involuntary out-of-network care. An inpatient contact with an out-of-network physician was defined as involuntary if (1) due to a medical emergency (excluding labor and delivery); (2) the physician's out-of-network status was unknown at the time of the contact (e.g., out-of-network status was not known until receiving the bill); or (3) an attempt was made to find an in-network physician in the hospital but none was available. Outpatient out-of-network contacts were defined as involuntary if the physician's out-of-network status was unknown at the time of the contact.

We used a purposeful random sampling approach (Patton 2001). A stratified sample was created using a random number generator in SAS and two characteristics identified in adjusted multivariable logistic regression of the survey data to be associated with involuntary use: self-reported health status and marital status. KnowledgeNetworks staff contacted potential participants and arranged a time for the telephone interview. Participants were recruited in two waves, and the final sample size was determined by theoretical saturation (Morse 1995) or the point at which no new information emerged through subsequent interviews. Of the first 40 potential participants submitted to KnowledgeNetworks, 20 interviews were completed, with multiple attempts to contact nonresponders. Twenty-five additional potential participants were then selected; of these, 8 interviews were completed. A small monetary incentive ($10) was provided. Verbal informed consent was obtained at the beginning of the interview and the study protocol was approved by the Yale University Human Investigation Committee.

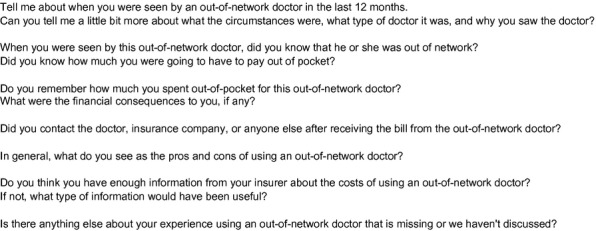

All interviews were completed by one researcher (K. K.), using a semi-structured interview guide (Britten 1995); each interview began with a broad question inviting the participant to share details of an experience with an out-of-network physician (Figure 1). Probes were used to help participants clarify and elaborate on their experiences. If a participant had used more than one out-of-network doctor, details were obtained about each experience. As is common in qualitative research, the interview guide evolved throughout the course of data collection, informed by prior interviews (Patton 2001). Demographic information was available from survey results. Interviews were approximately of 20 minutes’ duration, were audio-taped, transcribed by a professional transcription service, and then reviewed for accuracy by the interviewer.

Figure 1.

Interview Guide

The analytic team consisted of three researchers, including one primary care physician and health services researcher (K. K.) and two public health graduate students (D. P. and K. B.), each with training in qualitative research. Analysis was conducted upon completion of data collection. Codes were created inductively using the constant comparative method of analysis, in which essential concepts from interview data are coded and compared over successive interviews to extract recurrent themes across the data (Miles and Huberman 1994; Patton 2001; Bradley, Curry, and Devers 2007). Each member of the coding team read the transcript independently and coded line by line. The team met regularly to review independent codes, resolving discrepancies through discussion and negotiated consensus. As the process continued, the code structure was revised as needed to capture novel concepts, expand and merge existing concepts until a final structure was established. A senior methodologist (L. C.) periodically reviewed the code structure for completeness and logic. All three researchers then again independently applied the final code structure to all transcripts, and consensus was obtained for any remaining discrepancies. Final coded data were entered into qualitative analysis software (ATLAS.ti version 6.2, Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany) to facilitate data organization and retrieval.

Results

Twenty-six interviews were used in the analysis: one participant was not eligible as a key informant as she denied ever using an out-of-network doctor; another was excluded due to poor audio recording. Table 1 presents characteristics of the participants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Participants

| Characteristic | Result n (%) |

|---|---|

| Total | 26 (100) |

| Age | |

| 18–29 | 1 (4) |

| 30–49 | 4 (15) |

| 50–64 | 21 (81) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 3 (12) |

| Female | 23 (88) |

| Race | |

| White | 21 (81) |

| Non-white | 5 (19) |

| Marital status | |

| Married/living with partner | 16 (62) |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 6 (23) |

| Never married | 4 (15) |

| Education | |

| High school or less | 1 (4) |

| Some college | 12 (46) |

| Bachelor's degree or higher | 13 (50) |

| Income (per year) | |

| <$35,000 | 1 (4) |

| $35,000–$59,000 | 5 (19) |

| $60,000–$100,000 | 9 (35) |

| >$100,000 | 11 (42) |

| Residence in metropolitan area | |

| Yes | 19 (73) |

| No | 7 (27) |

| Region of country | |

| Northeast | 4 (15) |

| Midwest | 11 (42) |

| South | 6 (23) |

| West | 5 (19) |

| Health status (self-reported) | |

| Excellent, very good, or good | 15 (58) |

| Fair or poor | 11 (42) |

Four recurrent themes characterize the perspective of individuals who experienced involuntary out-of-network physician charges: (1) responsibilities and mechanisms for determining network participation are not transparent; (2) physician procedures for billing and disclosure of physician out-of-network status are inconsistent; (3) serious illness requiring emergency care or hospitalization precludes ability to choose a physician or confirm network participation; and (4) resources for mediation of involuntary charges once they occur are not available.

Theme 1: Responsibilities and Mechanisms for Determining Network Participation Are Not Transparent

Participants described lack of understanding regarding responsibilities for determining a physician's network participation, particularly for inpatient care. The most common experience was the assignment of an out-of-network physician at an in-network hospital; participants assumed that all physicians caring for them would be in-network:

“I just never even questioned who was going to do what because I knew the hospital was in network, I knew this doctor that was doing the procedure was in the network and because the hospital was in network that means their anesthesiologists are all in-network. And I just assumed that pathology would be in-network also. But that was an assumption that I guess I shouldn't have made.” [Participant #27]

The appropriate mechanism for identifying a physician's network status was not clear to participants seeking care from hospital-affiliated physicians such as anesthesiologists, radiologists, or pathologists (these physicians may be assigned rather than chosen by the participant and/or not have contact with the participant). One woman who involuntarily used an out-of-network anesthesiologist during a surgery pre-authorized by her insurance with an in-network surgeon at an in-network hospital describes that even after her experience, she does not know how to prevent additional charges in the future:

INTERVIEWER: So in the future, how do you think you would do anything differently?

RESPONDENT: I suppose I could ask the [surgeon]…But I don't know if the surgeon would even know. If you ask the surgeon who is the anesthesiologist, she probably wouldn't know…if they're on the list. And I don't even know would the hospital give me the name of the anesthesiologist so that I could call. I don't know. And say, are they on the list? You're just kind of in a catch 22.” [Participant #15]

This theme extended to the outpatient setting as well. One participant reflected on an experience where she was billed in-network by an ophthalmologist at one office location and out-of-network at his other office:

“It's the same human being that I saw, I just saw him in his other office, not my, and, and the two places have different names… His office is in a different town and he works at one office 3 days a week and the other office 2 days a week. So it didn't seem like there should be any problem but my insurance was not, saying this was out-of-network and I'm like, no. It was out of town but it was the same doctor. How could it be out-of-network if it's the same doctor?” [Participant #22]

The physical location of a facility next to his in-network physician's office led another participant to assume that this was an in-network facility:

“I went to the doctor for my pre-op exam and all that and he was networked. On the day of the surgery, they instructed me not to come into his door. Come to the door that's immediate prior to his door, that's the surgical center. So I went in there and I had the surgery. Upon receiving the bills, I found out the doctor was in-network, which I knew, but I assumed the surgical center would be in the network also because they were next door to each other in the same building. And the difference being is my out of pocket is like $1,500 for the year in network and $5,000 out of pocket out of network. Which meant I paid an extra $3,500 by going in that next door.” [Participant #25]

Theme 2: Physician Procedures for Billing and Disclosure of Physician Out-of-Network Status Are Inconsistent

Participants described confusion and frustration with the variation between physicians in their disclosure of network participation. Timing for when cost and insurance participation were reviewed varied: some physicians discussed insurance prior to the visit, others after the participant had already seen the physician.

Poor communication between office staff and participants also contributed to confusion regarding the participant's financial responsibilities. Participants inquired whether the physician “takes my insurance” intending to confirm in-network participation, yet office staff did not necessarily share this interpretation of the question. In the following example, one participant using an out-of-network rheumatologist incurred substantial involuntary out-of-pocket expenses and ultimately switched practices as a result of her frustration:

“We had switched insurances and I said, do you guys take this insurance? And they told me yes. So I went, saw him for a regular doctor visit and all of a sudden I get a big bill from him. … And I called the office and she said, well we do take your insurance but out-of-network. Well, why didn't you tell me that when I called and asked?… So I ended up having to pay that bill too and switch doctors.” [Participant #10]

Billing and reimbursement procedures were also not consistently transparent to participants. Participants related how some physicians accepted payment at the in-network rate for out-of-network visits whereas others did not. Based on her prior experience, this participant was surprised to receive additional charges from an out-of-network anesthesiologist for her surgery with an in-network hospital and surgeon:

“I came home from the hospital and I would say within a week after my coming home, I received a bill in the mail from this doctor and the doctor is telling me I owe $200.00 … and then she billed me for almost $500.00. … I received an explanation of benefits from [name of insurer] telling me that they're paying X amount of dollars because she was an out-of-network doctor. Well in the past, if I had an out-of-network doctor, especially one that I didn't know about, the doctor just accepted whatever the insurance company gave.” [Participant #1]

Theme 3: Serious Illness Requiring Emergency Care or Hospitalization Precludes Ability to Choose a Physician or Confirm Network Participation

Participants reported involuntary charges in the context of severe illness or other incapacitation that prevented them from verifying that a physician was in-network or required them to use the first available or closest physician. Many participants related experiences with out-of-network emergency room use; these included injuries or illness during vacations outside of their local area or within their area but requiring immediate attention that prevented them from accessing an in-network hospital.

However, emergency situations resulting in involuntary out-of-network charges were not limited to the emergency room. In contrast, one participant who was directly admitted to the hospital by her primary care physician after being seen in the office for pneumonia was unaware that the out-of-network hospitalization charges would have been covered by her insurer if she had gone through the emergency room:

“I went to my doctor, and they sent me to the hospital. So if I would have gone through the Emergency Room, I probably would not have had that problem. … And that's a problem because I didn't realize then. If I was just going into the Emergency Room, I'd have been okay.” [Participant # 6]

Many participants felt that it should not be their responsibility to determine whether a physician is in their network or to be responsible for out-of-network charges for nonelective hospitalization or emergency care:

“Because that was kind of an emergency situation, where…the doctor decided that my husband was really sick enough to be hospitalized, because by that time he had streaks running up his arm. It was pretty serious. And, you know, at that point in time, I was concerned about my husband. I wasn't thinking about insurance. Do you know what I mean? And I think they should take things like that into consideration. Because I think most people would think the same way I was thinking, would be concerned for their relative or whoever it is that's going into the hospital and not concerned with insurance right at that point.” [Participant #20]

In contrast, for elective or outpatient care, participants assumed the responsibility of determining whether a physician is in-network:

“I don't think it's fair that just because you have to go out of network, I can see if you go out of network when you're in your hometown because you choose to do so. But I had no choice. So that I couldn't believe what I had to pay … And I can understand if I just decided, well, I want to go try this doctor. But I don't think it's fair [when] it's a life or death situation, or at least I thought it was. And we have no choice and they still sting you with it.” [Participant #7]

Theme 4: Resources for Mediation of Involuntary Charges Once They Occur Are Not Available

Outcomes of disputed out-of-network charges varied widely from the insurer covering any additional costs, a discounted fee or payment plan provided by the physician, to lack of any success in reducing the charge and payment in full.

Participants often invested significant energy and time in disputing involuntary out-of-network charges. In some instances, informal advocates emerged during the process; for example, one participant's in-network surgeon helped dispute her out-of-network anesthesiology charges for her operation. More commonly, participants lacked an advocate and ultimately gave up and paid the bill. One woman who received out-of-network charges from an emergency room physician at an in-network hospital describes her experience disputing the charges:

“I called the insurance company and they told me, nope there was nothing they can do. I sent …the doctor himself a letter, explaining everything. They wouldn't give me a discount, nothing.” [Participant #10]

Discussion

We sought to characterize the experiences of patients who encountered involuntary out-of-network physician charges. We found substantial patient confusion and frustration in several areas: determining whether a physician was in-network, understanding the patient responsibility for out-of-pocket charges, and identifying mechanisms to dispute involuntary out-of-network charges once they occurred.

These findings suggest important considerations for state and federal regulators as well as other stakeholder groups such as employers, insurers, and physicians in addressing involuntary out-of-network care. First, for most privately insured, the onus of responsibility for determining a physician's or facility's network participation is with the patient rather than with the physician or insurer. Participants in our study did not understand this responsibility, particularly for inpatient care. For example, for an elective surgery, one participant was not aware that she needed to verify network participation of the anesthesiologist in addition to her primary surgeon. Additional confusion occurred when out-of-network services were provided at an in-network hospital, or if the physician was assigned and the patient not given an opportunity to choose among available physicians. This suggests that more aggressive patient education initiatives may be required, or that the onus of disclosure be shifted on to the physician. Several states have passed legislation requiring physician disclosure of out-of-network status prior to delivery of services (Texas SB 1731 2007; Louisiana Act No. 354 2009) and their impact on involuntary out-of-network care should be evaluated.

Second, when disclosure of network participation or billing did occur, participants found it to be inconsistent. Some physician offices disclosed after the visit rather than before. Terminology such as whether physicians “take my insurance” was interpreted differently by office staff and patients. This suggests a need for standardization of when disclosure should occur and clear explicit language when communicating with patients. Ideally, an estimate of charges would be provided prior to services, although many patients found this information difficult to obtain when requested from front desk staff.

Third, we found that patients were unable to choose an in-network physician during serious illness. This is generally acknowledged among policy makers for emergency room care; most states have held harmless provisions for HMO enrollees for emergency room care and recently, the Affordable Care Act prohibits plans from imposing higher copayment or coinsurance for out-of-network emergency room physicians, although balance billing is allowed (Federal Register 2010). However, our findings suggest that serious illness extends beyond the emergency room. Patients may be directly admitted by a primary care physician, or already be admitted and require input from a specialist. Future policy goals should focus on these scenarios in addition to emergency room care.

Finally, this study identifies a lack of a clear advocate or mediator in disputing involuntary out-of-network charges. While insurers often agreed to reimburse for additional costs over the in-network rate or physicians reduced their charges, this was not always the case. For some patients, formal mediators such as a state advocate or insurance commissioner office may be available, but patients do not know to access these resources. These state-level resources could be more widely published in insurer and human resources literature, or potentially included on Explanation of Benefit forms for out-of-network services. Texas requires the availability of a mediator for out-of-network charges from hospital-based physicians if the service was in an in-network hospital and over $1,000 (after deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance); this policy could be extended to other states if shown to reduce financial burden from involuntary out-of-network care.

This study has several limitations. The majority of participants were women; however, our findings are related to overarching issues that are unlikely to be experienced by men in systematically different ways. Half of our survey respondents initially agreed to be contacted further and did not differ from those who refused based on demographic characteristics or whether they experienced involuntary care. However, those who eventually completed the in-depth interviews may have been more likely to have had exceptionally challenging experiences with out-of-network care. There was also variation in the length of time that had transpired since the participant had contact with the out-of-network physician and the degree to which participants were able to report details relating to their experiences. Because we used a qualitative approach, our findings are not generalizable to all privately insured individuals. Future quantitative studies on larger representative samples are needed to test our hypotheses.

Our research also has a number of strengths. Participants were from all regions of the United States and were diverse with regard to income level, education, and health status. We used several techniques to ensure rigor: use of a multidisciplinary team, audio-taping and independent transcription, standardized coding and analysis, and an audit trail to document analytic decisions (Patton 2001; Curry, Nembhard, and Bradley 2009).

Insurance provider networks are intended to steer patients to high-quality low-cost providers and yet preserve patients’ choice of physician. Cost savings from enrolling in a network plan are lost when the use of an out-of-network physician is involuntary. In this study, we identify systems-level factors impacting involuntary out-of-network physician use; these insights may be of use to policy makers as they work to protect patients from unexpected, sometimes financially burdensome, costs.

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: This study was supported by a grant from the Women's Health Research at Yale Pilot Project Program and funding from the Yale Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program. The sponsors were not involved in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. Dr. Kyanko has accepted consulting fees from the Consumers Union, a nonprofit organization dedicated to consumer protection, and FAIR Health Inc, an independent, nonprofit organization with the mission to ensure fairness of out-of-network reimbursement. These consulting activities are in topic areas outside of the submitted manuscript, but both entities may be perceived to have interest in the manuscript content. Ms. Pong, Ms. Bahan, and Dr. Curry have no financial disclosures.

Disclosures: None.

Disclaimers: None.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Table S1: Characteristics of Survey Respondents Consenting to Future Contact for Interviews.

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

References

- Americas Health Insurance Plans. 2013. “Survey of Charges Billed by Out-of-network Providers: A Hidden Threat to Affordability.” [accessed on May 20, 2013]. Available at http://www.ahip.org/Value-of-Provider-Networks-Report-2012/

- Andrews M. “Insurers Sometimes Reject Neonatal Intensive Care Costs”. Kaiser Health News. 2011 [accessed May 20, 2013]. Available at http://www.kaiserhealthnews.org/Features/Insuring-Your-Health-michelle-andrews-on-neonatal-ICU-health-costs.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Appleby J. “Consumers Hit By Higher Out-of-Network Medical Costs”. Kaiser Health News/USA Today. 2012 [accessed on May 20, 2013]. Available at http://www.kaiserhealthnews.org/Stories/2012/February/09/consumers-hit-by-higher-out-of-Network-medical-costs.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. “Qualitative Data Analysis for Health Services Research: Developing Taxonomy, Themes, and Theory”. Health Services Research. 2007;42(4):1758–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britten N. “Qualitative Research: Qualitative Interviews in Medical Research”. British Medical Journal. 1995;311(6999):251–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6999.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, Clark VLP. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Curry LA, Nembhard IM, Bradley EH. “Qualitative and Mixed Methods Provide Unique Contributions to Outcomes Research”. Circulation. 2009;119(10):1442–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.742775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Register. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2010. “Rules and Regulation: Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act; Requirements for Group Health Plans and Health Insurance Issuers under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act Relating to Preexisting Condition Exclusions, Lifetime and Annual Limits, Rescissions, and Patient Protections; Final Rule and Proposed Rule.” Vol. 75, No. 123. [Google Scholar]

- Hoadley J, Lucia K, Schwartz S. Oakland, CA: California HealthCare Foundation; 2009. “Unexpected Charges: What States Are Doing about Balance Billing”. [Google Scholar]

- KnowledgeNetworks. 2011. “Methodological Papers, Presentations, and Articles on KnowledgePanel” [accessed on July 8, 2011]. Available at http://www.knowledgenetworks.com/ganp/reviewer-info.html.

- Kyanko KA, Busch SH. “The Out-of-Network Benefit: Problems and Policy Solutions”. Inquiry Winter 2012/2013. 2013;49(4):352–61. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_49.04.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyanko KA, Curry LA, Busch SH. “Out-of-Network Physicians – How Prevalent Are Involuntary Use and Cost Transparency?”. Health Services Research. 2012;48((3)):1154–72. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12007. Oct 22. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12007. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louisiana Act No. 354. 2009. “SB 282.”.

- McDevitt R, Gabel J, Gandolfo L, Lore R, Pickreign J. “Financial Protection Afforded by Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance: Current Plan Designs and High-Deductible Health Plans”. Medical Care Research and Review. 2007;64(2):212–28. doi: 10.1177/1077558706298292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 2nd Edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Morse JM. “The Significance of Saturation”. Qualitative Health Research. 1995;5(2):147–9. [Google Scholar]

- New York State Department of Financial Services. 2012. “An Unwelcome Surprise: How New Yorkers Are Getting Stuck with Unexpected Medical Bills from Out-of-network Providers.” [accessed May 20, 2013]. Available at http://www.governor.ny.gov/assets/documents/DFS/20Report.pdf.

- Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pope C, Mays N. “Qualitative Research: Reaching the Parts Other Methods Cannot Reach: An Introduction to Qualitative Methods in Health and Health Services Research”. British Medical Journal. 1995;311(6996):42–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6996.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raeburn P. “Code Blue: Out-of-Network Charges Can Spur Financial Emergency”. Kaiser Health News. 2009 [accessed May 20, 2013]. Available at http://www.kaiserhealthnews.org/Stories/2009/August/19/out-of-Network.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Texas HB 2256. 2009. “Relating to Mediation of Out-of-network Health Benefit Claim Disputes Concerning Enrollees, Facility-Based Physicians, and Certain Health Benefit Plans; Imposing an Administrative Penalty. Session 81(R).”.

- Texas SB 1731. 2007. “Relating to Consumer Access to Health Care Information and Consumer Protection for Services Provided by or Through Health Benefit Plans, Hospitals, Ambulatory Surgical Centers, Birthing Centers, and Other Health Care Facilities, and Funding for Health Care Information Services; Providing Penalties. Session 80(R).”.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.