Abstract

Little research has investigated changes in subjective distress during cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for anxiety disorders in youth. In the current study, 40 youth diagnosed with primary obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD; M age=11.9 years, 60% male, 80% Caucasian) and 36 parent informants completed separate weekly ratings of child distress for each OC symptom during a 12-session course of CBT. Between-session changes in distress were calculated at the start of, on average throughout, and at the end of treatment. On average throughout treatment, child- and parent-reported decreases in child distress were significant. Baseline OCD severity, functional impairment, and internalizing symptoms predicted degree of change in child distress. Additionally, greater decreases in child distress were predictive of more improved clinical outcomes. Findings advance our understanding of the strengths and limitations of this clinical tool. Future studies should examine youth distress change between and within CBT sessions across both subjective and psychophysiological levels of analysis.

Keywords: cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), childhood, subjective units of distress (SUDS), fear thermometer

1. Introduction

The assessment of symptom-based distress is utilized widely in cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBT) for childhood anxiety disorders including obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) (e.g., Barrett, Farrell-Healy, & March, 2004; Brown et al., 2008; Kendall & Hedtke, 2006; Kendall, Hudson, Gosch, Flannery-Schroeder, & Suveg, 2008; Piacentini, Langley, & Roblek, 2007; POTS Team, 2004). As in adulthood, OCD in youth involves obsessions and/or compulsions that are impairing and distressing. Obsessions are intrusive and repetitive thoughts, impulses, or images, whereas compulsions are repetitive behaviors or mental acts that serve to decrease the distress or perceived harm associated with obsessions (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). The foundation of CBT for OCD is exposure and response prevention (ERP), which entails triggering particular obsessions (exposure) and helping the child to resist the associated compulsions (response prevention) in order to disrupt the negative reinforcement cycle associated with compulsion-related distress reduction (Foa, Steketee, Grayson, Turner, & Latimer, 1984; Meyer, 1966). At the start of therapy, the assessment of distress related to specific OC symptoms informs the construction of a symptom hierarchy whereby ERP tasks are traditionally completed in a graduated manner across subsequent sessions. When working with children, the therapist typically asks the patient to rate distress associated with each symptom using a simple scale (e.g., 0 to 10), sometimes referred to as a “fear thermometer” or Subjective Units of Distress Scale (SUDS) (Barrios & Hartmann, 1988; Kendall et al., 2005; Kircanski, Peris, & Piacentini, 2011; Wolpe, 1973).

Typically thereafter and on an ongoing basis throughout CBT, the therapist continues to evaluate subjective distress. One common methodology, examined herein, involves obtaining SUDS ratings for each hierarchy symptom from the child and the child’s parent/guardian as an informant at the start of each subsequent session (e.g., Piacentini et al., 2007). In addition, the child may provide distress ratings at the onset, during, and at the offset of each ERP task (e.g., Kendall et al., 2005). The former methodology provides information regarding between-session changes in distress, whereas the latter methodology also provides data regarding within-session changes. Theoretically, it is purported that over the course of successive ERP sessions, distress and arousal should gradually attenuate through autonomic habituation while corrective learning about the stimulus is facilitated (Foa & Kozak, 1986; Foa & McNally, 1996). The therapist may therefore highlight reductions in distress during therapy in order to demonstrate the concept of habituation and enhance the patient’s confidence in treatment.

Yet, despite its pervasiveness in practice, the clinical relevance of assessing child subjective distress has received little empirical examination. Only two studies have explored the precise nature of changes in reported distress during CBT for childhood anxiety disorders and whether such changes are related to other clinical factors. These are important issues to consider, given that a recent review of the adult exposure therapy literature found only partial evidence that the average degree of habituation between sessions predicts clinical improvement, and no consistent evidence that the degree of habituation within session predicts clinical improvement (Craske et al., 2008). Similar reviews have yet to be completed for childhood anxiety disorders given the relative lack of research on this topic with youth. Of further interest, changes in reported distress may be more or less pertinent at different points during treatment; for example, data with adults suggests that treatment outcome may be more highly associated with changes in subjective distress at later than at initial sessions (Hayes, Hope, & Heimberg, 2008; Norton, Hayes-Skelton, & Klenck, 2011). Therefore, the present study focused on between-session changes in distress at the start of treatment, on average throughout treatment, and at the end of treatment. In addition, given that parent-child symptom agreement has been shown to be low (Canavera, Wilkins, Pincus, & Ehrenreich-May, 2009), we utilized parallel session-by-session SUDS ratings from youth with OCD and their parents.

In the most relevant previous study to date, Benjamin et al. (2010) evaluated several facets of subjective distress in youth ages 7 to 14 participating in a 16-session CBT protocol for child non-OCD anxiety disorders. At each session, youth gave SUDS ratings (on a 0 to 8 scale) prior to the onset of exposure, at each two minutes during exposure, and at the offset of exposure. Parent-reported SUDS data were not reported. Between exposure sessions, maximum SUDS was found to increase, whereas degree of change in SUDS (i.e., decrease in distress) was found to amplify. In addition, higher self-reported anxiety at baseline was associated with greater SUDS decrease during the initial exposure session, whereas a primary diagnosis of GAD was associated with lesser SUDS decrease between sessions. Other factors such as diagnostic severity and overall functional impairment did not predict SUDS changes. The authors suggested that their pattern of results may have been related to clinical guidelines within the treatment manual employed (Kendall & Hedtke, 2006), including the goal to reduce distress within sessions by 50% and the use of imaginal exposures for patients with GAD.

An earlier experiment investigated changes in reported distress in four children with OCD receiving ERP and parent-involved treatment using a multiple baseline design (Knox, Albano, & Barlow, 1996). When aggregating youth’s daily SUDS ratings across hierarchy items, symptom distress showed a gradual decrease over the course of treatment, and for the majority of sessions within-session habituation was also observed. However, greater between-session SUDS decreases did not predict lower fear ratings following treatment.

In sum, there is clearly a need for further research in youth examining the reduction of subjective distress during treatment and its relation to clinically relevant variables. Drawing from the broader child CBT literature, a recent review indicated that greater baseline OCD severity is associated with poorer response to CBT (Ginsburg, Kingery, Drake, & Grados, 2008). In addition, secondary analysis of the Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS Team, 2004), found that baseline functional impairment predicted poorer treatment response (Garcia et al., 2010). To our knowledge, the relations of OCD severity and functional impairment to changes in subjective distress over the course of CBT have yet to be examined in pediatric samples.

In order to address the gaps and inconsistencies in the extant literature, the present study aimed to: (1) characterize the nature of CBT-triggered reduction of subjective distress in children and adolescents with OCD; (2) examine baseline predictors of child- and parent-reported changes in child subjective distress during CBT; and (3) evaluate changes in child- and parent-reported child subjective distress during CBT as predictors of treatment outcome. Data were drawn from a randomized controlled trial of a standard CBT program for OCD in youth ages 8 to 17 years, which included ERP and parent participation in treatment (Piacentini et al., 2011; clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT00000386). Data for participants assigned to the CBT arm of the trial allowed for examination of changes in distress between ERP sessions and their relations to baseline and outcome variables.

Extrapolating from the theoretical and small empirical literature on this topic, we had several broad hypotheses. First, we hypothesized that child self-reported and parent-reported subjective distress would decrease between sessions (Benjamin et al., 2010; Knox et al., 1996), though child and parent ratings would not consistently correlate with each other (Canavera et al., 2009). Second, we expected that greater baseline OCD severity and functional impairment would predict lesser reductions in subjective distress (Garcia et al., 2010; Ginsburg et al., 2008), whereas greater baseline child internalizing symptoms would predict greater reductions in subjective distress (Benjamin et al., 2010). Although the hypotheses for baseline OCD severity and baseline internalizing symptoms may appear contradictory, we reasoned that these two constructs are distinct and may indeed have differing relations to changes in subjective distress. Whereas internalizing symptoms serve as a broader index of symptom severity that more closely resembles the construct assessed by Benjamin et al. (2010), OCD severity is a more specific index for which hypotheses were derived from the outcome literature on CBT for child OCD (Ginsburg et al., 2008). Finally, we expected that greater between-session reductions in subjective distress on average throughout treatment and at the end of treatment, but not at the start of treatment, would predict more favorable clinical outcomes (Hayes et al., 2008; Norton et al., 2011).

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Participants were 40 youth ages 8 to 17 years (M=11.9, SD=2.7) were recruited from a university-affiliated outpatient clinic specializing in the assessment and treatment of childhood OCD and related disorders, and 36 respective parent informants. Participants were drawn from a larger randomized controlled trial (RCT; N=71) comparing individual child cognitive-behavioral therapy plus a structured family component aimed at reducing accommodation of the child’s OCD symptoms (CBT) to psychoeducation plus systematic relaxation training (PRT) (Piacentini et al., 2011).1 At study entry, all youth met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th edition, text revision; DSM-IV-TR; APA, 2000) diagnostic criteria for a primary diagnosis of OCD; scored 15 or greater on the Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS; Goodman, Price, Rasmussen, Riddle, & Rapoport, 1991; Scahill et al., 1997) indicating at least moderate severity of OCD; had an IQ greater than 70; and were free of psychotropic medication directly targeting their OCD. Additional exclusion criteria included suicidality, psychosis, pervasive developmental disorder, mania, and/or substance dependence. At intake, all youth provided informed assent and parents provided informed consent regarding study participation. The present sample was 60% male, and 80% Caucasian, 10% Latino/a, 5% Asian, 2.5% African-American, and 2.5% Other/Mixed. Further information on the full RCT sample, including psychiatric comorbidity, is provided in Piacentini et al. (2011).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Subjective Units of Distress Scale (SUDS; Wolpe, 1973)

At the beginning of each CBT session, youth self-reported current subjective distress associated with each of their OC symptoms using a 0 to 10 “fear thermometer” scale (0=least distressing, 10=most distressing). For example, a child with an obsession involving excessive concerns about germs and contamination would rate the subjective level of distress generated by these concerns. Likewise, a child with a compulsion involving excessive and ritualized hand-washing would rate the level of distress generated by not performing this compulsion when the urge is triggered. Parents concurrently provided independent ratings of their child’s OC symptoms using the identical procedure and rating scale.2

2.2.2. Other Clinical Measures

2.2.2.1. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV

(ADIS-IV; Silverman & Albano, 1996) is a semi-structured diagnostic interview conducted separately with parent and child, and was used to gather data on diagnosis and severity of OCD and coexisting disorders. A clinical severity rating (CSR; range=0–8; Silverman & Albano, 1996) was assigned to each diagnosis for the purpose of determining the primary diagnosis, with a CSR of 4 or greater required for study entry. The ADIS-IV demonstrates good test-retest reliability (Silverman, Saavedra, & Pina, 2001) and concurrent validity (Wood, Piacentini, Bergman, McCracken, & Barrios, 2002).

2.2.2.2. Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale

(CY-BOCS; Scahill et al., 1997) is a clinician-administered semi-structured interview with child and parent that measures OCD severity (Gallant et al., 2008). The CY-BOCS comprises the most commonly-observed obsessions and compulsions and has a 5-item obsessions subscale, 5-item compulsions subscale, and 10-item total scale (range 0–40) assessing severity of illness over the previous week. Higher scores correspond to greater severity. The CY-BOCS has good reliability and validity (Scahill et al., 1997; Storch et al., 2004).

2.2.2.3. Child Obsessive Compulsive Impact Scale-Revised

(COIS-R; Piacentini, Peris, Bergman, Chang, & Jaffer, 2007) measures OCD-related functional impairment and includes child- and parent-report forms. In addition to child and parent form total scores, child form subscales of activities, school, and social, and parent form subscales of school, family/activities, social, and daily skills, were utilized. Higher scores correspond to greater functional impairment. Both child and parent forms have adequate internal consistency, validity, and reliability, and are sensitive to treatment (Piacentini et al., 2007, 2011).

2.2.2.4. Child Behavior Checklist

(CBCL; Achenbach, 1991) is a parent-report measure that covers domains of youth internalizing and externalizing problems, academic achievement, and social competence, and has demonstrated good validity, internal consistency, and test-retest reliability (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). Based on previous findings (Benjamin et al., 2010), parent t-scores regarding domains of internalizing symptoms (withdrawn behavior, somatic complaints, and anxious/depressed behavior) and total internalizing symptoms were utilized. Higher scores correspond to greater internalizing symptoms.

2.2.2.5. Clinical Global Impression - Improvement Scale

(CGI-I; NIMH, 1985). The CGI-I is a clinician-administered instrument that provides a broad measure of clinical improvement from baseline to post-treatment along a 1 to 7 scale (1=very much improved, 7=very much worse).

2.3. Procedure

2.3.1. Recruitment and baseline clinical assessment

Participants were recruited for the RCT through outreach efforts (e.g., flyers, print sadvertisements, mailings), with an emphasis on media outlets and providers serving minority populations in order to enhance the representativeness of the sample. Interested families completed a telephone screen to ascertain potential eligibility. Potentially eligible families then completed study consent/assent and baseline evaluation in the clinic. At baseline, an independent evaluator (IE) trained in the procedures detailed by the measure developers administered the ADIS-IV and the CY-BOCS under the supervision of one of the senior study investigators. IEs were doctoral-level clinical psychologists or graduate students trained in assessing anxiety disorders in youth. IE training entailed didactics on the assessment measures, co-rating a series of videotaped and live interviews, and conducting an evaluation while supervised by a trained diagnostician. IEs underwent group supervision throughout the study. A random selection of baseline CY-BOCS audiotapes (N=26) demonstrated excellent inter-rater reliability (ICC=.96).

In addition, each child and parent completed a battery of baseline clinical measures including those indicated above. Following determination of study eligibility, participants were randomized to 12 sessions over 14 weeks of either CBT or PRT.

2.3.2. CBT and SUDS assessment

CBT was administered by doctoral-level psychologists and advanced clinical psychology interns who received specialized training, including extensive review of the treatment manual (Piacentini et al., 2007) followed by treatment of a non-study patient under observation prior to treating study participants. All therapists underwent weekly group supervision. Ten percent of CBT session videotapes (N=53) were randomly selected and rated on adherence to the treatment manual (range=0–100) and overall quality (range=0–10). Ratings demonstrated good treatment adherence (M=88.2, SD=7.9) and quality (M=8.1, SD=1.1).

The CBT protocol comprised a manualized set of 12 90-minute sessions over 14 weeks, with the first 10 sessions occurring weekly and the last two sessions occurring biweekly to facilitate generalization and therapy termination (Piacentini et al., 2007). In order to comply with the treatment protocol, each child and parent were required to attend all sessions. Session 1 focused on joint psychoeducation with the child and parent about OCD and the rationale for ERP. Session 2 focused on creation of a symptom hierarchy for the child. In order to create the hierarchy, a list of all child OC symptoms was gathered from the CY-BOCS and clinical interview with the child and parent in a standardized manner. Next, the therapist asked the child to rate current level of distress associated with each obsession and compulsion using the SUDS.

Sessions 3 through 12 began with a standardized review of child functioning over the past week with the child and parent. Next, the therapist obtained separate SUDS ratings from the child and parent regarding current child level of distress associated with each obsession and compulsion on the symptom hierarchy. The subsequent 45–50 minutes of each session focused on individual child ERP, and the last 30 minutes centered on family didactics including parent psychoeducation, training in parent disengagement from child OC symptoms, and relapse prevention.

2.3.3. Post-treatment clinical assessment

At week 14 following the end of treatment, each child and parent completed a battery of outcome measures including the COIS-R. Children and their parents were also evaluated by IEs in order to ascertain changes in OCD severity using the CY-BOCS and responder status using the CGI-I. A random selection of post-treatment CY-BOCS audiotapes (N=23) demonstrated excellent inter-rater reliability (ICC=.99) at this assessment point.

2.4. Data Reduction and Statistical Analyses

The current study utilized child-reported and parent-reported SUDS data from Sessions 3 through 12. We did not use child-reported SUDS data from Session 2 as parent SUDS data were not collected nor had ERP started at this time point. Child-reported SUDS for each session (3 through 12) was calculated as the average of child SUDS ratings for all OC symptoms at that session. Child-reported SUDS change from each session to the next was calculated as the absolute difference in child-reported SUDS (e.g., Session 4 SUDS – Session 3 SUDS) such that negative values indicated decreases in SUDS from one session to the next. Between-session change(BSC) in child-reported SUDS at the start of treatment was calculated as the absolute difference in child-reported SUDS between Sessions 3 and 4 (CHILD FIRST BSC). BSC in child-reported SUDS on average throughout treatment was calculated as the mean of the absolute differences in child-reported SUDS between all successive sessions (CHILD AVG BSC). BSC in child-reported SUDS at theend of treatment was calculated as the absolute difference in child-reported SUDS between Sessions 11 and 12 (CHILD LAST BSC). BSC variables for parent-reported SUDS (PARENT FIRST BSC, PARENT AVG BSC, and PARENT LAST BSC) were calculated in parallel fashion.

Following creation of these variables, a series of t-tests and correlational analyses examined the nature of change in these variables. Next, a series of regression analyses were performed, for each of which a baseline clinical measure served as a predictor of a child- or parent-report SUDS variable. Finally, a series of regression analyses were performed, for each of which a child- or parent-report SUDS variable served as a predictor of a clinical outcome measure.3 No statistical correction for multiple tests was applied.

Due to the fact that no previous sample-based studies have examined SUDS change during CBT for childhood OCD in relation to baseline predictors and clinical outcomes, we were not able to estimate effect sizes and compute a priori the statistical power of our analyses. Therefore, we assessed the observed power of the analyses using the current sample size, α=.05, and the obtained effect sizes for the significant results.

3. Results

3.1. Nature of SUDS Changes

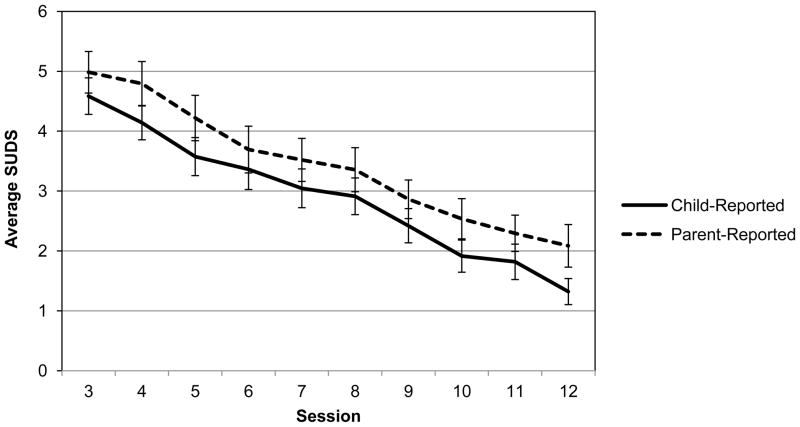

Figure 1 presents average child-reported and parent-reported SUDS from Sessions 3 to 12. Table 1 presents the raw values for the child-reported and parent-reported BSC variables. As expected, one-sample t-tests (test values=0) demonstrated that CHILD FIRST BSC, t(39)=−2.36, p<.05, CHILD AVG BSC, t(39)=−12.47, p<.001, CHILD LAST BSC, t(37)=−3.30, p<.001, and PARENT AVG BSC, t(35)=−6.66, p<.001, were all significantly negative, indicating a decrease in distress over the relevant time periods. However, PARENT FIRST BSC, t(31)=−1.00, ns, and PARENT LAST BSC, t(34)=−1.59, ns, were not significantly negative.

Figure 1.

Average child- and parent-reported SUDS ratings for Sessions 3 through 12. Error bars=±1 standard error.

Table 1.

Raw Values for SUDS Change Variables

| Mean | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHILD FIRST BSC | −.44 | 1.18 | −3.17, 4.22 |

| CHILD AVG BSC | −.37 | 0.19 | −.75, −.03 |

| CHILD LAST BSC | −.38 | 0.71 | −3.22, .43 |

| PARENT FIRST BSC | −.29 | 1.60 | −4.28, 3.38 |

| PARENT AVG BSC | −.33 | 0.30 | −.90, .39 |

| PARENT LAST BSC | −.22 | 0.81 | −1.75, 2.43 |

Note. CHILD FIRST BSC=absolute differences in child-reported SUDS between Sessions 3 and 4. CHILD AVG BSC=mean of absolute differences in child-reported SUDS between all successive sessions. CHILD LAST BSC= absolute differences in child-reported SUDS between Sessions 11 and 12. PARENT FIRST BSC=absolute differences in parent-reported SUDS between Sessions 3 and 4. PARENT AVG BSC=mean of absolute differences in parent-reported SUDS between all successive sessions. PARENT LAST BSC= absolute differences in parent-reported SUDS between Sessions 11 and 12.

Bivariate correlations indicated that CHILD AVG BSC and PARENT AVG BSC were significantly associated with one another, r=.43, p<.01, whereas the correlations between CHILD FIRST BSC and PARENT FIRST BSC, r=.10, ns, and CHILD LAST BSC and PARENT LAST BSC, r=.22, ns, were not statistically significant.

3.2. Baseline Predictors of SUDS Changes during Treatment

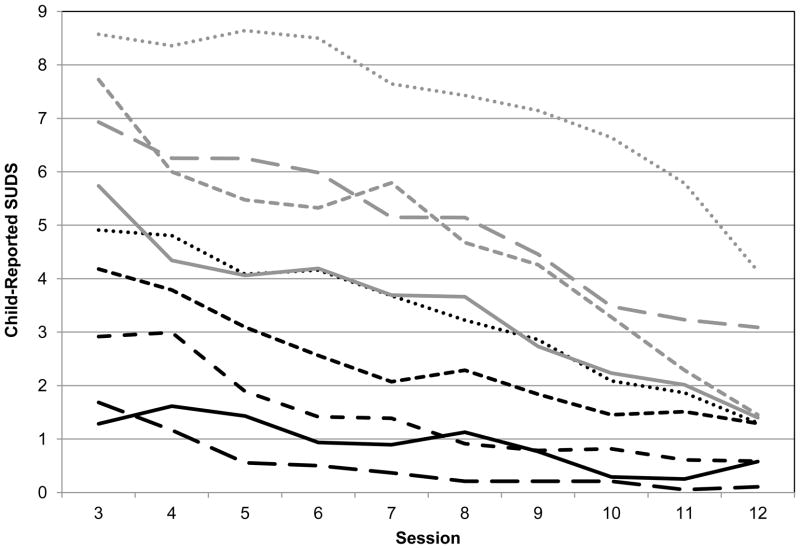

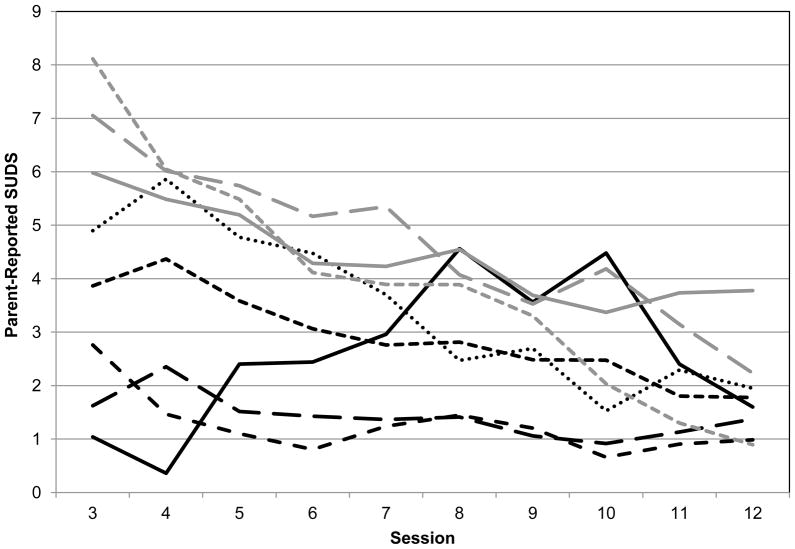

Figure 2 presents child-reported SUDS for Sessions 3 to 12 as a function of initial child-reported SUDS, and Figure 3 presents parent-reported SUDS for Sessions 3 to 12 as a function of initial parent-reported SUDS. To determine whether to partial the effects of initial SUDS ratings in the analyses examining predictors of BSC variables, a set of regression analyses examined whether the child- and parent-reported BSC variables were dependent on initial child- and parent-reported SUDS ratings, respectively. Higher session 3 child-reported SUDS predicted greater CHILD FIRST BSC, t=−2.70, p=.01, greater CHILD AVG BSC, t=−6.03, p<.001, and greater CHILD LAST BSC, t=−2.57, p<.05. Higher session 3 parent-reported SUDS predicted greater PARENT AVG BSC, t=−4.60, p<.001. Based on these results, Session 3 child-reported SUDS was included in the first step in all subsequent regression analyses of predictors of CHILD FIRST BSC, CHILD AVG BSC, and CHILD LAST BSC, and session 3 parent-reported SUDS was included in the first step in all subsequent analyses of predictors of PARENT AVG BSC. We also examined the number of OC symptoms at baseline, which did not predict between-session changes in any SUDS variables.

Figure 2.

Child-reported SUDS ratings for Sessions 3 through 12 as a function of initial (Session 3) SUDS ratings. Note. For graphing purposes, initial child-reported SUDS ratings were placed into bins according to their most proximal whole number.

Figure 3.

Parent-reported SUDS ratings for Sessions 3 through 12 as a function of initial (Session 3) SUDS ratings. Note. For graphing purposes, initial parent-reported SUDS ratings were placed into bins according to their most proximal whole number.

3.2.1. Child-reported betweens-session SUDS change

Table 2 presents all significant baseline predictors of BSC variables. As expected, greater parent-reported impairment in daily skills on the COIS-R predicted lesser CHILD AVG BSC, and higher baseline CBCL withdrawn behavior scores predicted greater CHILD AVG BSC. Contrary to expectation, higher baseline CY-BOCS obsessions scores predicted greater CHILD LAST BSC.

Table 2.

Significant Baseline Predictors of SUDS Change Variables

| β | t | p | SE | R2 change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHILD AVG BSC | |||||

| COIS-RP Daily Skills Impairment* | .34 | 3.17 | <.005 | .11 | .11 |

| CBCL Withdrawn Behavior* | −.24 | −2.06 | <.05 | .11 | .06 |

| CHILD LAST BSC | |||||

| CY-BOCS Obsessions | −.38 | −2.62 | .01 | .14 | .14 |

| PARENT AVG BSC | |||||

| COIS-R Parent-Report Daily Skills Impairment* | .37 | 2.76 | .01 | .13 | .13 |

| CBCL Social Problems | −.35 | −2.43 | <.05 | .14 | .11 |

| PARENT LAST BSC† | |||||

| COIS-R Parent-Report Social Impairment | −.46 | −2.86 | <.01 | .16 | .21 |

Note. CBCL=Child Behavior Checklist. COIS-R=Child Obsessive Compulsive Impact Scale-Revised. CY-BOCS=Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale.

Significant unique predictor.

R2 is given becauseSession 3 parent-reported SUDS was not partialed in the analysis as it was not a significant predictor of PARENT LAST BSC.

3.2.2. Parent-reported between-session SUDS change

As expected, greater parent-reported impairment in daily skills on the COIS-R predicted lesser PARENT AVG BSC, and higher baseline CBCL social problems predicted greater PARENT AVG BSC. Contrary to expectation, higher parent-reported COIS-R social impairment scores predicted greater PARENT LAST BSC.

3.2.3. Unique predictors

Multiple regression analyses were used to examine the unique contributions of the variables listed above to the prediction of CHILD AVG BSC and PARENT AVG BSC. Higher parent-reported COIS-R daily skills impairment (β=.38, t=3.88, p=.001) and higher CBCL withdrawn behavior scores (β=−.28, t=−2.85, p<.01) each emerged as unique predictors of CHILD AVG BSC. Parent-reported COIS-R daily skills impairment emerged as the only unique predictor of PARENT AVG BSC, β=.34, t=2.50, p<.05.

3.3. SUDS Changes in Relation to Treatment Outcome

3.3.1. Predictors of outcome

Session 3 child-reported SUDS was included in the first step in all regression analyses of CHILD FIRST BSC, CHILD AVG BSC, and CHILD LAST BSC as predictors of outcome, and session 3 parent-reported SUDS was included in the first step in all analyses of PARENT AVG BSC as a predictor of outcome. In addition, the baseline value of each outcome variable was included in the first step in all analyses of predictors of that outcome variable. Table 3 presents all BSC variables that were significant predictors of treatment outcome. As expected, greater CHILD AVG BSC and greater PARENT AVG BSC predicted greater clinical improvement as measured with the CGI-I and lower post-treatment CY-BOCS. In addition, greater CHILD AVG BSC predicted lower post-treatment COIS-R child-report total score, and greater PARENT AVG BSC predicted lower post-treatment COIS-R parent- and child-report total scores. Contrary to expectation, greater PARENT FIRST BSC predicted lower post-treatment COIS-R parent-report total score and lower post-treatment COIS-R child-report total score.

Table 3.

SUDS Change Variables as Predictors of Treatment Outcome

| β | t | p | SE | R2 change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CGI-I | |||||

| CHILD AVG BSC† | .75 | 3.98 | <.001 | .19 | .29 |

| PARENT AVG BSC | .60 | 2.78 | .01 | .22 | .21 |

| CY-BOCS | |||||

| CHILD AVG BSC | .61 | 2.94 | <.01 | .21 | .18 |

| PARENT AVG BSC* | .87 | 4.79 | <.001 | .18 | .43 |

| COIS-R Parent-Report Total Score | |||||

| PARENT FIRST BSC | .50 | 3.61 | .001 | .14 | .25 |

| PARENT AVG BSC* | .78 | 4.87 | <.001 | .16 | .35 |

| COIS-R Child-Report Total Score | |||||

| CHILD AVG BSC | .48 | 2.39 | <.05 | .20 | .12 |

| PARENT FIRST BSC | .35 | 2.22 | <.05 | .16 | .12 |

| PARENT AVG BSC | .60 | 3.03 | <.01 | .20 | .21 |

Note. CGI-I=Clinical Global Impression-Improvement Scale. COIS-R=Child Obsessive Compulsive Impact Scale-Revised. CY-BOCS=Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale.

Significant unique predictor.

Marginally significant unique predictor.

3.3.2. Unique predictors

A series of multiple regression analyses were used to examine the unique contributions of the variables listed above to the prediction of CGI-I, CY-BOCS, and COIS-R scores. Greater CHILD AVG BSC predicted marginally lower CGI-I, β=.48, t=1.88, p=.07. Greater PARENT AVG BSC predicted lower post-treatment CY-BOCS, β=.94, t=3.85, p=.001. As expected, greater PARENT AVG BSC, but not greater PARENT FIRST BSC, predicted lower post-treatment COIS-R parent-report total score, β=.62, t=3.47, p<.005.

3.4. Statistical Power

Finally, we computed the observed statistical power of the analyses, focusing on the significant results (G*Power 3.1; Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, 2007). For baseline predictors of SUDS change variables, the statistical power ranged from 33% to 89% likelihood of rejecting the null hypothesis. For SUDS change predictors of the clinical outcome measures, the statistical power was substantially higher and ranged from 62% to 99% likelihood of rejecting the null hypothesis.

4. Discussion

The present analyses aimed to expand upon the handful of prior studies examining the nature and clinical relevance of changes in subjective distress during CBT for childhood anxiety disorders. Overall, the hypotheses were partially supported, and the results suggest several potential directions for future empirical work. Below, study findings, limitations, and implications are discussed in the context of extant theory, research, and clinical practice.

4.1. The Nature of Child- and Parent-Reported Change

We found that, on average throughout CBT, child self-reported and parent-reported between-session changes in distress were both significant and were associated with one another. On the basis of previous research it was hypothesized that parent-child agreement would not always be high (Canavera et al., 2009), and indeed child-reported and parent-reported changes were not significantly correlated at either the start or end of treatment. As has been proposed for the other anxiety disorders, youth may be more likely than parents to rely on internal information (e.g., emotional state) when providing ratings of subjective distress, whereas parents may need to rely on more observable symptom characteristics (e.g., behavioral avoidance), thus lowering parent-child agreement (Choudhury, Pimental, & Kendall, 2003; Klein, 1991). This may also relate to the finding that parents did not report significant decreases in distress at the start or end of treatment; that is, it is possible that youth noted subtle changes in their internal state as a result of ERP that were not yet observable in their behaviors. Statistical considerations may also play a role, given that average changes throughout treatment were based on data aggregated across all ERP sessions, whereas changes at the start and end of treatment were based on data for only two sessions. Nevertheless, these results suggest that data aggregated across treatment, in comparison to data collected at only one or two time points in treatment, may reveal stronger associations between child- and parent-reported variables. These notions are perhaps underscored by Figures 1 to 3; whereas session-by-session SUDS data averaged across participants suggest relative agreement between youth and parents, these data disaggregated based on initial SUDS value were more variable, particularly with respect to parent-reported distress.

4.2. Predictors of Change in Distress

We had several hypotheses concerning the relations of baseline clinical variables to between-session changes in distress. As expected, greater OCD-associated functional impairment, albeit specific to parent-reported daily skills impairment, uniquely predicted lesser child- and parent-reported decreases in distress on average throughout treatment. This finding builds upon previous treatment outcome research (Garcia et al., 2010) by suggesting that greater functional impairment may also negatively impact symptom distress at the process level during treatment (however, see Benjamin et al., 2010). On the COIS-R, the parent-report daily skills subscale may have been sufficiently broad and objective to encompass a range of everyday situations in which childhood OCD symptoms may interfere, thus allowing this subscale to serve as a more robust predictor across participants, relative to the other subscales that focused on more specific types of impairment.

Hypotheses regarding the relations among child internalizing symptoms and changes in distress were also generally supported. Parent-reported CBCL withdrawn behavior uniquely predicted greater child-reported decreases in distress, and parent-reported CBCL social problems predicted greater parent-reported decreases in distress. Drawing on a proposal by Benjamin et al. (2010), children who report or exhibit more internalizing symptoms at baseline may be more agreeable to or motivated for CBT. The present findings extend this proposal to youth with OCD and suggest that withdrawn behavior and social problems, rather than internalizing symptoms broadly defined, may serve as specific predictors of decreases in subjective distress.

Regarding other OCD characteristics, it was surprising that higher baseline CY-BOCS obsessions score predicted greater child-reported decreases in distress at the end of treatment, and that higher parent-reported COIS-R social impairment predicted greater parent-reported decreases in distress at the end of treatment. Viewed encouragingly, it is possible that certain types of initially severe and/or interfering symptomatology may have sustained room for improvement at the end of treatment, whereas less severe symptomatology may have reached floor levels. In addition, it is important to note that the level of parent involvement in the current CBT protocol was relatively unique, in that it included 30 minutes of parent and family didactics during Sessions 3 through 12. This greater family involvement in CBT may have enabled parents to be more attuned to their child’s symptoms, level of distress, and functional impairment. In turn, this greater parental attunement may have contributed to differing findings between this study and the Benjamin et al. (2010) study of individual child CBT, in which baseline functional impairment was not a significant predictor of changes in SUDS ratings. Other distinctions between these two studies may also be related to the differing findings for baseline predictors. For example, Benjamin et al. (2010) assessed both within- and between-session changes in distress and examined distress in non-OCD anxiety disorders. Whereas distress in non-OCD anxiety disorders chiefly revolves around affective states of fear and/or anxiety, distress in OCD may involve a number of different affective states including fear and anxiety as well as disgust and discomfort (reviewed in Cisler, Olatunji, & Lohr, 2009; Leckman et al., 1994). It is possible that any differences between OCD and non-OCD anxiety disorders in the precise nature of distress may contribute to divergent findings for baseline predictors.

4.3. Distress Change and Treatment Outcome

Finally, we expected that greater between-session reductions in subjective distress on average throughout treatment and at the end of treatment, but not at the start of treatment, would predict better clinical outcome. Our findings were mixed. First, we found that more favorable clinical outcomes – assessed via post-treatment clinician-rated improvement, OCD severity, and overall functional impairment – were indeed predicted by greater child- and parent-reported between-session decreases in distress on average throughout treatment. However, contrary to our hypotheses, we found that greater reductions in functional impairment were also predicted by parent-reported decreases in distress at the start of treatment, but not at the end of treatment. These findings diverge from those of a previous experiment with four children with OCD that demonstrated no relation of between-session distress reduction to post-treatment fear ratings (Knox et al., 1996), and contradict those of studies of exposure outcome in adults (Hayes et al., 2008; Norton et al., 2011). Such inconsistent results are common within the exposure therapy literature and may be related to methodological differences across studies (Craske et al., 2008). Of note, the adult studies assessed distress during actual exposure, whereas the current study assessed symptom-based distress at the start of each session. In addition, the adult studies assessed distress change across three exposure sessions that varied across participants in their timing during treatment, whereas the current study examined distress change across 10 sessions of CBT that were standardized in their timing. Such differences in timing of the “first” and “last” sessions may contribute to these contradictory results. Further CBT process research in both youth and adults is needed to resolve these inconsistencies.

4.4. Study Implications

Taken together, the current findings suggest that between-session changes in child self-reported and parent-reported distress may index some aspects of inhibitory learning in CBT for childhood OCD. The results thus support one of the purported clinical purposes of this assessment tool (e.g., Barrett, Farrell-Healy, & March, 2004; Brown et al., 2008; Kendall & Hedtke, 2006; Kendall, Hudson, Gosch, Flannery-Schroeder, & Suveg, 2008; Piacentini et al. 2007; POTS Team, 2004), and suggest several reasons why it may prove clinically useful to gather SUDS ratings from child and parent informants throughout CBT for childhood OCD. Perhaps most notably, the child- and parent-reported SUDS change variables on average throughout treatment were consistently predictive of several outcome measures. Therefore, therapists may find it helpful to continually track between-session SUDS change, and to use this information to help guide and enhance treatment. For instance, if overall SUDS does not appear to change over the course of multiple sessions or appears to increase between sessions over time, therapists may use this information along with any additional data to consider an enhancement of the treatment approach, such as intensifying ERP in and/or out of session or emphasizing additional components of treatment (e.g., cognitive restructuring). It is important to note, however, that the prediction of outcomes by SUDS change variables was not perfect, but rather explained a range of 12% to 43% of the variation in outcomes in this study. Therefore, SUDS change should not be used as the only piece of information driving treatment planning and decision making. Indeed, another proposal from the adult exposure therapy literature is that improvements in the ability to tolerate any given level of distress, which is distinct from change in level of distress, may be an important predictor of long-term inhibitory learning (reviewed in Craske et al., 2008). In addition, it is important that therapists gather information from both youth and parents when possible, as these sources of information are not always correlated and appear to predict treatment outcomes in distinct ways. In particular, parent-reported changes on average throughout CBT emerged as a unique predictor of clinical outcomes, perhaps because in order to index distress, parents may utilize more observable or overt symptom characteristics that overlap with constructs assessed at treatment outcome. Finally, SUDS is a relatively straightforward and cost-free assessment tool that therapists, youth, and parents were able to apply in the current study, improving its utility and generalizability in community settings.

4.5. Study Limitations

This study had several key limitations that may be improved upon in future research. First, we found that no baseline variables predicted decreases in distress at the start of treatment. Similar to the argument of Benjamin et al. (2010), this lack of significant findings may relate to a general clinical guideline employed at the initial exposure session to target a low-level symptom and reduce distress significantly in order to illustrate the concept of habituation. It is also possible that some effects were not significant once initial distress ratings were partialed in the regression analyses. In addition, statistical power calculations indicated a wide range of observed power for those analyses of baseline predictors that were significant. This wide range, combined with the fact that the current sample size was smaller than that of Benjamin et al. (2010), may have decreased the ability to detect any additional significant predictive associations in this study. Notably, however, reduction in parent-reported distress at the start of treatment was associated with more improved functional impairment post-treatment. Second, there is also a possibility of Type I error in this study. Given that our hypotheses for baseline and outcome associations with SUDS were relatively focused, we did not apply a statistical correction for multiple tests. Third, although our measures of change in distress were somewhat broad in capturing both child- and parent-report changes and changes at different points in treatment, the study did not measure within-session change during ERP and did not utilize psychophysiological variables, both of which warrant further study. Fourth, the current sample was comprised of primarily Caucasian youth and the treatment was delivered by highly trained therapists, which may not be applicable to all clinical settings. Fifth, we allowed for variability in youth’s specific symptom profiles and ERP tasks, thus it is not known whether these findings are more or less powerful for specific clinical presentations or procedures.

4.6. Additional Implications and Future Directions

The variability across participants in this study is also a potential strength, in that the measures of change and associations with change were robust enough to be obtained within a sample of youth with diverse symptom presentations and severity of OCD undergoing a full randomized controlled trial of CBT. Together, these findings speak to multiple literatures, including those on parent-child agreement in the assessment of anxiety disorder symptomatology and the CBT process literature for youth with anxiety disorders. These results highlight the need for more extensive and sophisticated study of inhibitory learning in exposure therapy, and the ways in which this learning process may in itself change or be maintained across development.

Highlights.

We examine changes in subjective distress throughout CBT for childhood OCD.

On average during CBT children and parents both report decreases in child distress.

Baseline OCD severity and impairment predict degree of change in child distress.

Decreases in several child distress measures are predictive of better CBT outcomes.

Findings indicate both strengths and limitations of this clinical assessment tool.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by National Institute of Mental Health grant R01MH58549-01 (J.P.). The authors wish to acknowledge the study research team and the children and families who participated in this research. Disclosures: Dr. Kircanski has received research support from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Dr. Piacentini has received grant support from NIMH, the Tourette Syndrome Association (TSA), and the Obsessive Compulsive Foundation book royalties from Guilford Press and Oxford University Press, including the manual described in this paper, and serves on the speakers’ bureau for the TSA. Trials Registry Information: Behavior Therapy for Children and Adolescents with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD); http://www.clinicaltrials.gov; NCT00000386.

Footnotes

Of the 41 participants who completed CBT, one child did not have usable SUDS data and four parent informants did not have usable SUDS data, due to data recording errors.

In the event that two parents were present during treatment, they provided a single rating of child subjective distress associated with each OC symptom.

With respect to clinical outcome measures, one participant was missing CY-BOCS data, one participant was missing COIS-R data and CBCL data, one participant was missing selected subscales of the COIS-R and CBCL data, and two participants were missing selected subscales of the COIS-R. These data were missing due to isolated issues or errors in measure administration or completion during the outcome assessments. For the analyses of each outcome measure, we included only participants with complete data.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4–18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. text rev. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett P, Healy-Farrell L, March J. Cognitive-behavioral family treatment of childhood obsessive-compulsive disorder: A controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:46–62. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200401000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrios B, Hartmann D. Fears and anxieties. In: Mash E, Terdal L, editors. Behavioral assessment of childhood disorders: Selected core problems. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1988. pp. 196–262. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin C, O’Neil K, Crawley S, Beidas R, Coles M, Kendall P. Patterns and predictors of subjective units of distress in anxious youth. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2010;38:497–504. doi: 10.1017/S1352465810000287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R, Antonuccio D, DuPaul G, Fristad M, King C, Leslie L, McCormick G, Pelham W, Piacentini J, Vitiello B. Childhood Mental Health Disorders: Evidence Base and Contextual Factors for Psychosocial, Psychopharmacological, and Combined Interventions. Washington DC: American Psychological Association Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Canavera KE, Wilkins KC, Pincus DB, Ehrenreich-May JT. Parent-child agreement in the assessment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2009;38:909–915. doi: 10.1080/15374410903258975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury M, Pimentel S, Kendall P. Parent-child agreement for diagnosis of anxiety disorders based on structured clinical interview. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42:957–964. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046898.27264.A2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisler JM, Olatunji BO, Lohr JM. Disgust, fear, and the anxiety disorders: A critical review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29:34–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Kircanski K, Zelikowski M, Mystkowski J, Chowdhury N, Baker A. Optimizing inhibitory learning during exposure therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008;46:5–27. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39:175–191. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa E, Kozak M. Emotional processing of fear: Exposure to corrective information. Psychological Bulletin. 1986;99:450–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, McNally RJ. Mechanisms of change in exposure therapy. In: Rapee R, editor. Current controversies in the anxiety disorders. New York: Guilford; 1996. pp. 329–343. [Google Scholar]

- Foa E, Steketee G, Grayson J, Turner R, Latimer P. Deliberate exposure and blocking of obsessive compulsive rituals: Immediate and long-term effects. Behavior Therapy. 1984;15:450–472. [Google Scholar]

- Gallant J, Storch E, Merlo L, Ricketts E, Geffken G, Goodman W, Murphy T. Convergent and discriminant validity of the Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale-Symptom Checklist. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2008;22:1369–1376. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia AM, Sapyta JJ, Moore PS, Freeman JB, Franklin ME, March JS, Foa EB. Predictors and moderators of treatment outcome in the Pediatric Obsessive Compulsive Treatment Study (POTS I) Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49:1024–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg GS, Kingery JN, Drake KL, Grados MA. Predictors of treatment response in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47:868–878. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181799ebd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman W, Price L, Rasmussen S, Riddle M, Rapoport J. Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS) New Haven, CT: Yale University; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SA, Hope DA, Heimberg RG. The pattern of subjective anxiety during in-session exposures over the course of cognitive-behavioral therapy for clients with social anxiety disorder. Behavior Therapy. 2008;39:286–299. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall P, Hedtke K. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxious children: Therapist manual. 3. Ardmore, PA: Workbook Publishing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall P, Hudson J, Gosch E, Flannery-Schroeder E, Suveg C. Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disordered youth: A randomized clinical trial evaluating child and family modalities. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:282–297. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Robin J, Hedtke K, Suveg C, Flannery-Schroeder E, Gosch E. Considering CBT with anxious youth? Think exposures. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2005;12:136–148. [Google Scholar]

- Kircanski K, Peris TS, Piacentini JC. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder in children and adolescents. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2011;20:239–254. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein R. Parent-child agreement in clinical assessment of anxiety and other psychopathology: A review. Journal of Anxiety Disorders Special Issue: Assessment of Childhood Anxiety Disorders. 1991;5:187–198. [Google Scholar]

- Knox L, Albano A, Barlow D. Parental involvement in the treatment of childhood compulsive disorder: A multiple-baseline examination incorporating parents. Behavior Therapy. 1996;27:93–114. [Google Scholar]

- Leckman JF, Grice DE, Barr LC, de Vries AL, Martin C, Cohen DJ, et al. Tic-related vs. non-tic-related obsessive-compulsive disorder. Anxiety. 1994;1:208–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer V. Modification of expectations in cases with obsessive rituals. Behavioral Research and Therapy. 1966;4:270–280. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(66)90023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Mental Health. Clinical global impression scale. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1985;21:839–843. [Google Scholar]

- Norton PJ, Hayes-Skelton SA, Klenck SC. What happens in session does not stay in session: Changes within exposures predict subsequent improvement and dropout. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2011;25:654–660. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pediatric OCD Treatment Study Team. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, sertraline, and their combination for children and adolescents with obsessive–compulsive disorder: The Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292:1969–1976. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.16.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piacentini J, Bergman RL, Chang S, Langley A, Peris T, Wood JJ, McCracken J. Controlled comparison of family cognitive behavioral therapy and psychoeducation/relaxation training for child obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50:1149–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piacentini J, Langley A, Roblek T. Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Childhood OCD. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Piacentini J, Peris TS, Bergman RL, Chang S, Jaffer M. The Child Obsessive Compulsive Impact Scale-Revised (COIS-R): Development and psychometric properties. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36:645–653. doi: 10.1080/15374410701662790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scahill L, Riddle MA, McSwiggan-Hardin MT, Ort SI, King RA, Goodman WK, et al. Children’s Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale: Reliability and validity. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:844–852. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199706000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman W, Albano AM. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Parent Version. San Antonio, TX: Graywing; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman W, Saavedra L, Pina A. Test-retest reliability of anxiety symptoms and diagnoses with anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV: Child and parent versions. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40(8):937–944. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200108000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch E, Murphy T, Geffken G, Soto O, Sajid M, Allen P, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale. Psychiatry Research. 2004;129:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolpe J. The Practice of Behavior Therapy. London: Pergamon Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Wood J, Piacentini J, Bergman RL, McCracken J, Barrios V. Concurrent validity of the anxiety disorders section of the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Child and Parent Version. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2002;31:335–342. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3103_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]