Abstract

Human social interactions are complex behaviors requiring the concerted effort of multiple neural systems to track and monitor the individuals around us. Cognitively, adjusting our behavior based on changing social cues such as facial expressions relies on working memory and the ability to disambiguate, or separate, representations of overlapping stimuli resulting from viewing the same individual with different facial expressions. We conducted an fMRI experiment examining brain regions contributing to the encoding, maintenance and retrieval of overlapping identity information during working memory using a delayed match-to-sample (DMS) task. In the overlapping condition, two faces from the same individual with different facial expressions were presented at sample. In the non-overlapping condition, the two sample faces were from two different individuals with different expressions. fMRI activity was assessed by contrasting the overlapping and non-overlapping condition at sample, delay, and test. The lateral orbitofrontal cortex showed increased fMRI signal in the overlapping condition in all three phases of the DMS task and increased functional connectivity with the hippocampus when encoding overlapping stimuli. The hippocampus showed increased fMRI signal at test. These data suggest lateral orbitofrontal cortex helps encode and maintain representations of overlapping stimuli in working memory while the orbitofrontal cortex and hippocampus contribute to the successful retrieval of overlapping stimuli. We suggest the lateral orbitofrontal cortex and hippocampus play a role in encoding, maintaining, and retrieving social cues, especially when multiple interactions with an individual need to be disambiguated in a rapidly changing social context in order to make appropriate social responses.

Keywords: prefrontal, social interaction, fMRI, delayed match-to-sample

The ability to perceive, maintain and distinguish between different instances of encountering an individual is critical from both memory and social cognition perspectives. For example, in addition to being able to recognize a friend and distinguish one friend from another, it is also important that we identify changing moods in individuals by separately encoding changing facial expressions over both short and long term social interactions. The hippocampus and orbitofrontal cortex may be critical to guiding appropriate real world social behavior during social gatherings when we need to monitor the changing facial expressions of an individual. Animal studies suggest the hippocampus disambiguates, or separates, overlapping sequences (Agster et al., 2002; Bower et al., 2005; Ginther et al., 2011; Wood et al., 2000) and neuroimaging studies show hippocampal activation when learning (Kumaran and Maguire, 2006; Shohamy and Wagner, 2008) and retrieving (Brown et al., 2010; Ross et al., 2009) overlapping sequences. Additionally, neuroimaging studies (LoPresti et al., 2008; McIntosh et al., 1996; Olsen et al., 2009; Ranganath and D’Esposito, 2001; Ranganath et al., 2005; Schon et al., 2004; 2005; 2012; Stern et al., 2001), studies in patients with medial temporal lobe damage (Hannula et al., 2006; Hartley et al., 2007; Nichols et al., 2006; Olson et al., 2006a,b) and electrophysiological recordings (Axmacher et al., 2009) suggest the hippocampus is involved during the maintenance of information in working memory. Together, the findings that the hippocampus is involved in working memory and during the disambiguation of overlapping stimuli in long-term memory suggests the hippocampus may be involved when using social cues to disambiguate multiple presentations of the same person over short delay periods.

In addition to the hippocampus, the orbitofrontal cortex may also be a critical region when disambiguating two encounters with the same individual in working memory. The orbitofrontal cortex is central to theories of social reinforcement learning (Kringelbach and Rolls, 2003; Rolls, 2004; 2007; Tabbert et al., 2005). Importantly, the maintenance of socially relevant information such as faces (Courtney et al., 1996; Haxby et al., 2000; LoPresti et al., 2008; Sala et al., 2003) and emotional expressions (LoPresti et al., 2008) over short delays activates the orbitofrontal cortex. Along with its role in processing social information, the orbitofrontal cortex has been linked to the disambiguation of overlapping representations in long term memory. Lateral orbitofrontal cortex is more strongly functionally connected to the hippocampus when retrieving disambiguated overlapping sequences (Brown et al., 2012; Ross et al., 2011) from long term memory. Additionally, the orbitofrontal cortex is critical for tasks where interference caused by repeated stimulus exposures must be overcome, such as in reversal learning (Berlin et al., 2004; Chudasama and Robbins, 2003; Fellows and Farah, 2003; Hornak et al., 2004; McAlonan and Brown, 2003; Meunier et al., 1997; Rudebeck and Murray, 2008; Schoenbaum et al., 2003; Tsuchida et al., 2010), proactive interference (Caplan et al., 2007), and delayed non-match-to-sample working memory tasks when the stimulus sets used are small (Otto and Eichenbaum, 1992; LoPresti et al., 2008; Schon et al., 2008). Together, the findings that the orbitofrontal cortex is involved in mnemonic tasks where interference is present and that the orbitofrontal cortex is important for processing social cues suggests the orbitofrontal cortex may interact with the hippocampus to create, maintain, and retrieve overlapping representations of the same individual seen with multiple facial expressions in working memory.

To investigate hippocampal and orbitofrontal cortex contributions to the encoding, maintenance and retrieval of overlapping identity information during working memory, participants performed a modified delayed match-to-sample working memory task with pairs of face stimuli. In the overlapping condition (OL), participants viewed a pair of pictures of the same individual shown with two different facial expressions. Importantly, the non-overlapping condition (NOL) consisted of two different faces with two different facial expressions. After the sample phase, participants remembered the pair of stimuli across a short delay period. At test, participants indicated whether a test face matched one of the sample faces shown before the delay. By comparing the overlapping and non-overlapping conditions, brain responses active during the disambiguation of two overlapping representations of the same person encountered with two different facial expressions during working memory encoding, maintenance, and retrieval could be examined. We also conducted a functional connectivity analysis to determine whether the orbitofrontal cortex and hippocampus work together when disambiguating overlapping stimuli in working memory. The results of the study provide insight into the brain mechanisms responsible during social situations where it is important to keep different encounters with the same individual separate.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Eighteen healthy individuals (seven male; mean age = 19.2 years, SD = 1.17 years) with no history of neurological or psychiatric illness were recruited from the Boston University population for this study. Vision was either normal or corrected to normal. All participants were screened for MRI environment compatibility. Eligible individuals who agreed to participate gave signed informed consent in accordance with the Human Research Committee of the Massachusetts General Hospital and the Institutional Review Board of Boston University. One participant was unable to complete the study due to fMRI scanner malfunction and another participant was eliminated from the study due to excess motion during scanning, leaving sixteen participants for analysis.

Procedure

Stimuli

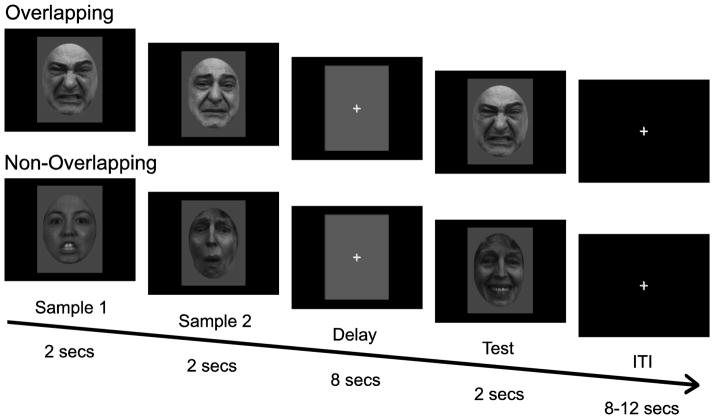

Stimuli for the task were selected from the University of Pennsylvania database of facial expressions (Gur et al., 2002) and other databases (Ekman and Friesen, 1976; Lyons et al., 1998; Pantic et al., 2005). We selected a range of expressions from 120 individuals for a total of 200 unique stimuli that appear in only 1 trial of the task. All stimuli were cropped to 350 x 467 pixels at 28.35 pixels/cm resolution (12.35 cm x 16.47 cm), put on a grey background, and converted to grey-scale. An oval mask was used to remove peripheral features (e.g. hair, clothes, eye color) and isolate the central facial features (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Delayed match-to-sample (DMS) task showing trials where identity information was overlapping (OL) and non-overlapping (NOL). A trial consisted of 3 time-locked components: a sample period where two faces were presented sequentially for 2 seconds each, an 8 second delay period and a 2 second test period where a single face was presented. Trials were separated by 8, 10, or 12 second inter-trial intervals (ITI). During OL trials, participants were presented with a pair of sample faces from the same individual with different expressions. During NOL trials, participants were presented with a pair of sample faces from two different individuals with different expressions. In order for a trial to be a match, both the identity and facial expression of the test face had to match one of the two sample faces. Non-match trials contained test stimuli that were the same identity as one of the two sample faces, but with a different expression. The OL trial shown in the top panel is an example of a match trial, and the NOL trial (bottom panel) is an example of a non-match trial.

Stimuli Pre-exposure

Prior to scanning, participants were pre-exposed to neutral expressions from all 120 individuals used in the study in order to familiarize them with each face identity. These neutral expressions were not used in the scanning task. Pre-exposure consisted of presenting all 120 individual faces with neutral expressions three times while participants made a male/female judgment, a young/old judgment and an attractive/not attractive judgment. The judgments were made in order to encourage participants to attend to the faces.

Delayed match-to-sample task

Participants performed a modified delayed-match-to-sample task (DMS) during fMRI scanning (Fig. 1). Each trial consisted of a pair of sample faces presented sequentially for 2 seconds each, followed by an 8-second delay period, followed by a single test face presented for 2 seconds. A variable length (8, 10, or 12 s) inter-trial interval (ITI) separated each trial. The task consisted of two conditions that differed only in the type of faces presented during the sample phase. In the overlapping condition (OL), two images of the same individual were shown with two different facial expressions. The non-overlapping (NOL) condition differed by presenting two individuals with two different expressions. During the test period, participants were instructed to press “1” if the test face matched the first sample face presented, press “2” if the test face matched the second sample face presented, or to press “3” if the test face did not match either of the sample faces. Non-match trials contained test stimuli that were the same identity as one of the two sample faces, but with a different expression. Overlapping/non-overlapping conditions, match/non-match trials, and facial expressions were counterbalanced across 5 fMRI runs. Participants performed 16 trials per run for a total of 80 trials (40 OL and 40 NOL). Participants viewed task instructions and performed a practice version of the task during structural scanning. Responses and reaction times (RT’s) were recorded from an MRI compatible button box. Tasks were designed and presented and behavioral data were recorded with E-Prime2 (Psychology Software Tools, Inc., Pittsburgh, PA).

fMRI Data Acquisition

Imaging was conducted on a 3.0 Tesla Siemens MAGNETOM TrioTim scanner (Siemens AG, Medical Solutions, Erlanger, Germany) with a 12-channel Tim® Matrix head coil at the Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging (Massachusetts General Hospital, Charlestown, MA). Two high-resolution T1-weighted multiplanar rapidly acquired gradient echo (MP-RAGE) structural scans were acquired using generalized autocalibrating partially parallel acquisitions (GRAPPA) (TR = 2.530 s, TE = 3.44 ms, flip angle = 7º, slices = 176, field of view = 256 mm, resolution = 1 x 1 x 1 mm). Cognitive tasks were performed during functional T2*-weighted gradient-echo, echo-planar blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) scans (TR = 2 s, TE = 30 ms, flip angle = 90º, acquisition matrix = 64 x 64, field of view = 256 mm, slices = 32 interleaved axial-oblique, resolution = 4 x 4 x 4 mm, no interslice gap). Slices were aligned parallel to the line connecting the anterior and posterior commissures and 192 images per run were acquired.

fMRI Data Analysis

Preprocessing

Functional imaging data were preprocessed and statistically analyzed using the SPM8 software package (Statistical Parametric Mapping, Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, London, UK). All BOLD images were first reoriented so the origin (i.e. coordinate xyz = [0 0 0]) was at the anterior commissure. The images were then corrected for differences in slice timing and realigned to the first image collected within a series. Motion correction was conducted next and included realigning and unwarping the BOLD images to the first image in the series in order to correct for image distortions caused by susceptibility-by-movement interactions. Realignment was estimated using 2nd degree B-spline interpolation with no wrapping while unwarp reslicing was done using 4th degree B-spline interpolation with no wrapping. The high-resolution structural images were then coregistered to the mean BOLD image created during motion correction and segmented into white and gray matter images. The bias-corrected structural images and the coregistered BOLD images were then spatially normalized into standard MNI (Montreal Neurological Institute) stereotactic space using the parameters derived during segmentation with resampling of the BOLD images to 2 x 2 x 2 mm isotropic voxels. Finally, BOLD images were spatially smoothed using a 6 mm full-width at half-maximum Gaussian filter to reduce noise.

fMRI Statistical Analysis

Analysis of fMRI activity during the DMS task was assessed with multiple regression using the SPM8 software package (collinearity between the delay regressor and the sample and test regressors was 0.20). We used positive stick functions convolved with a Gamma hemodynamic response function (HRF) (Boynton et al., 1996) in MATLAB 7.5 (The Mathworks, Inc., Natick, MA) to create 12 regressors that model the 6 components of the task (sample1, sample2, delay, test match, test non-match, and ITI) for each of the 2 conditions (overlapping and non-overlapping). In addition, delay regressors were separated into four 1/4th size stick functions spread across the 4 TRs (8 seconds) of the delay period to account for the sustained time-course and expected weaker signal during this phase of the task (LoPresti et al., 2008; Schluppeck et al., 2006). The 5 fMRI runs were concatenated in time and treated as a single times series. Additional regressors were included in the model to account for run number.

Linear contrasts were constructed to compare the overlapping condition to the non-overlapping condition at the sample and delay periods of the task (i.e. OL sample > NOL sample; OL delay > NOL delay). Due to collinearity between the regressors for sample1 and sample2, contrasts of the sample component consist of a combination of both regressors. During the test period, participants were asked to identify the stimulus shown as a match or a non-match to the stimuli presented in the sample phase. At test, only the OL and NOL match trials were compared (OL Match>NOL Match). Group analysis was performed on each component of the task by entering the contrast images from each participant into a second-level random-effects one-sample t-test, treating participant as a random factor. Regions within the anterior medial temporal lobes (the amygdala, entorhinal cortex and parts of perirhinal cortex) and anterior medial parts of the orbitofrontal cortex were not included because of signal dropout.

Functional Connectivity Analysis

Functional connectivity was assessed using the beta series correlation analysis method (Rissman et al., 2004). The beta series correlation method uses the magnitude of the task-related BOLD response for each individual trial to create a beta series. The method assumes the extent to which two brain voxels interact during a given condition can be quantified by the extent to which their respective condition-specific beta series are correlated. In order to conduct the beta series correlation analysis, we created a model where each individual trial of the sample, delay, and test match trials was modeled separately for the overlapping and non-overlapping conditions. Only correct trials were used in the model so the number of regressors for each individual participant varied anywhere between 172 and 209 regressors. Additional regressors included as part of the design matrix were two regressors accounting for test non-match trials in the overlapping and non-overlapping conditions, two regressors for the inter-trial intervals in the overlapping and non-overlapping conditions, a nuisance regressor comprised of the sample, delay and test onsets of incorrect trials, and 5 run regressors. All these regressors were then convolved with the canonical hemodynamic response function in SPM8 and filtered with a 0.008 Hz high-pass filter. In order to limit the amount of collinearity between the sample, delay and test regressors, the first image in the sample was set as the onset for each sample regressor while the onset point of the delay regressor was set to the 2nd TR of the delay. Each regressor was modeled as a “stick” function (i.e. zero duration). Parameter estimates, or beta values, were computed for each regressor using the least squares solution of the GLM in SPM8. We then sorted these beta values into the individual trials of the sample, delay, and test match periods of the overlapping and non-overlapping conditions for the beta series correlation analysis. Beta series were formed within regions of interest (ROI, see below) by concatenating the beta values for the individual trials of each condition (OL, NOL) and event (sample, delay, test) in chronological order.

We wished to determine regions showing differential functional connectivity with the orbitofrontal cortex in the overlapping compared to the non-overlapping condition at sample, delay and test. We functionally defined ROIs as 5 mm spheres centered at peak voxel coordinates in orbitofrontal cortical regions identified in the univariate analysis. At sample, we examined functional connectivity with the right lateral orbitofrontal cortex (BA 47/12; MNI coordinate 44, 40, −10). At delay, functional connectivity was assessed with right lateral orbitofrontal cortex (BA 11L) at MNI coordinate 32, 42, −4. There were two orbitofrontal cortical regions examined for functional connectivity during test match trials, the right and left lateral orbitofrontal cortex (BA 47/12; MNI coordinate ±46, 34, 0). Eight correlation maps, one for each of the four ROIs for the overlapping and non-overlapping conditions, were constructed by determining the correlation of each of the ROIs beta series with the beta series of all other voxels in the brain using a custom MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA) script provided by Dr. Jesse Rissman. These correlation maps then underwent an arc-hyperbolic tangent transformation to normalize the values in the correlation maps. The arc- hyperbolic transformed correlation coefficients were then divided by the standard deviation to produce a map of z-scores. These z-score maps reflect how well each voxel in the brain is functionally connected to the orbitofrontal cortex ROI in the overlapping and non-overlapping conditions separately.

The primary goal of the functional connectivity analysis was to determine whether the lateral orbitofrontal cortex was more strongly functionally connected to the hippocampus, caudate, and putamen when disambiguating overlapping social cues (overlapping vs. non-overlapping condition). Therefore, we used the Volumes toolbox for SPM (http://sourceforge.net/projects/spmtools/) to extract the correlation z-scores from each of the 8 orbitofrontal cortex correlation maps (sample, delay, and 2 test coordinates for the overlapping and non-overlapping condition) from the hippocampus (±30,−4,−15), caudate (±12,22,−6) and putamen (±20,18,−6) bilaterally in 5 mm radius spheres. We used individual ANOVAs on the extracted correlation z-scores for the sample, delay, and test periods to assess statistical significance. The hippocampal, caudate and putamen coordinates used for the analysis were derived from two papers illustrating orbitofrontal-hippocampal and orbitofrontal-striatal functional connectivity during the disambiguation of long-term memories (Ross et al., 2011; Brown et al., 2012). A 2 x 2 x 3 repeated measures ANOVA with condition (overlapping and non-overlapping), hemisphere (right and left) and region (hippocampus, caudate, and putamen) was conducted on the correlation z-values extracted from the orbitofrontal cortex connectivity maps at sample and delay separately. At test, two separate 2 x 2 x 3 ANOVAs were run, one for each orbitofrontal cortical correlation map (right and left lateral orbitofrontal cortex), with condition, hemisphere, and region as factors. We also ran a group level analysis to assess whole brain differences in orbitofrontal cortical functional connectivity between the overlapping and non-overlapping conditions. The whole brain analysis was accomplished by conducting paired-sample t-tests contrasting overlapping with non-overlapping functional connectivity within SPM8 using the z-transformed correlation maps of orbitofrontal cortex connectivity at sample, delay and test match trials.

A cluster extent threshold was enforced in order to correct for multiple comparisons for both the univariate and whole brain functional connectivity analyses. Specifically, an individual voxel statistical threshold of p ≤ 0.01 was enforced with a minimum cluster extent threshold of 88 voxels (704 mm3) to correct for multiple comparisons at p ≤ 0.05. Therefore, at a voxel threshold of p ≤ 0.01, the probability of observing a cluster extent larger than 88 voxels was p ≤ 0.05. The cluster extent was calculated using a Monte Carlo simulation with 10,000 iterations run in MATLAB (Slotnick et al., 2003). The Monte Carlo simulation modeled activity in each voxel using a normally distributed random number (mean = 0 and variance = 1). Type I error was assumed to be equal to the individual voxel threshold p value (p ≤ 0.01) in a volume defined by the functional acquisition dimensions (64 x 64 x 32 with 4 mm isotropic original voxels resampled to 2 mm isotropic voxels with no masking). Spatial autocorrelation in the data was calculated for each participant and averaged about 7.5 mm after smoothing. Therefore, we used an 8 mm full width half maximum three dimensional Gaussian kernel in the Monte Carlo simulation.

Peaks within each cluster of activation after multiple comparison correction were identified in SPM8. Peaks of activation were reported if they were more than 4 mm apart and represented a different region of activity. If a specific region of activity had multiple peaks within a cluster, the peak with the highest t-value was reported. Brodmann areas were identified visually using a variety of reference materials (Damasio, 2005; Ongur et al., 2003; Petrides, 2005, Scheperjans et al., 2008).

Behavioral Analysis

Accuracy and reaction times (RTs) were recorded for each trial in E-prime 2.0. A 2 x 2 repeated measures ANOVA with condition (overlapping and non-overlapping) and trial type (match and non-match) was used to assess differences in accuracy and reaction time individually. Pairwise comparisons and paired sample t-tests were used as post-hoc tests where appropriate. The alpha level was set to p ≤ 0.05. All ANOVA’s and post-hoc tests were conducted using PASW 18, version 18.0.0 (IBM Corporation, NY). When more than four post-hoc tests were conducted for an individual ANOVA, p-values were Bonferonni adjusted within PASW 18.

Results

Behavioral Performance

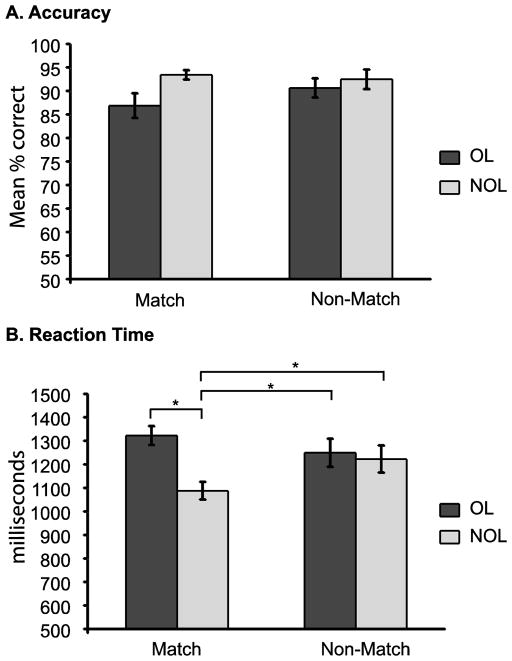

The 2 x 2 repeated measures ANOVA examining accuracy revealed a significant main effect of condition (F(1,15) = 9.060, p = 0.009) where participants did significantly better on non-overlapping (mean ± S.E.M.: 93.0 ± 1.0%) than overlapping trials (88.8 ± 1.7%). However, there was no main effect of trial type (match vs. non-match) nor was there a condition x trial type interaction. Some of the errors made in the overlapping condition were errors where participants correctly identified the test stimulus as a match but incorrectly indicated the temporal order (i.e the participant indicated the test stimulus matched the first sample instead of the second sample or vice versa). The number of these types of errors was small (3.7 % or 2 trials per participant) precluding the possibility of using them as a condition for comparison. A 2 x 2 repeated measures ANOVA with condition (overlapping or non-overlapping) and stimulus order (1st or 2nd stimulus shown at sample) illustrated no effect of stimulus order in performance on match trials (F(1,15) = 4.099, p > 0.05). However, there was a significant condition x stimulus order interaction (F(1,15) = 5.196, p ≤ 0.05). The interaction was caused by a significant decrease in performance when the test stimulus in the overlapping trials was a match for the first stimulus (mean ± SEM; 81.9 ± 3.6%) shown at sample compared to when the test stimulus matched the second stimulus (90.9 ± 2.3%) at sample. The non-overlapping condition showed no difference in performance based on which sample picture was the match stimulus (1st sample 93.1 ± 2.2; 2nd sample 93.8 ± 1.4). The pattern of this interaction effect suggests that seeing a second stimulus with the same identity but a different facial expression is causing interference which then needs to be resolved. There was also a main effect of condition for reaction times (F(1,15) = 52.230, p ≤ 0.001) as well as a condition x trial type interaction (F(1,15) = 79.451, p ≤ 0.001). The main effect of condition and the condition x trial type interaction were driven by significantly faster reaction times for match trials in the non-overlapping condition than the three other conditions as assessed by paired sample t-tests (OL match; t(15) = 10.811, p 0.001, OL non-match; t(15) = 3.862, p ≤ 0.01, and NOL non-match; t(15) = 3.543, p ≤ 0.01, Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Behavioral performance during delayed match to sample task. A. Mean percent correct for overlapping (dark grey bars) and non-overlapping (light grey bars) conditions during match and non-match trials. B. Reaction times (msec) for overlapping (dark grey bars) and non-overlapping (light grey bars) conditions during match and non-match trials. * indicate significant differences between comparisons. Error bars = standard error of the mean. Significance level was set at p ≤ 0.05.

fMRI Univariate Analysis Results

Encoding of overlapping stimuli in working memory

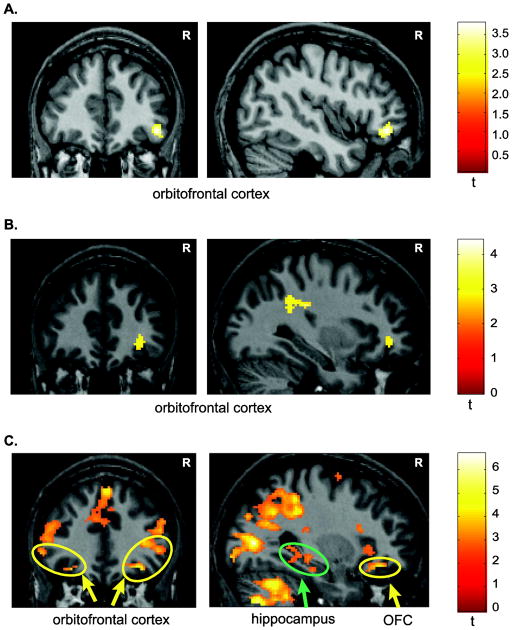

Brain regions responsible for encoding overlapping representations of the same individual shown with two different facial expressions during working memory were identified by contrasting the OL and NOL sample regressors (sample1 and sample2) and revealed significant activation in the right lateral orbitofrontal cortex (OFC; xyz = 44, 40, −10; Fig. 3A). No other brain region showed a significant difference in activation after correcting for multiple comparisons (Table 1).

Figure 3.

Statistical parametric maps showing significantly greater fMRI activity during the disambiguation of overlapping stimuli in working memory. A. fMRI activation in the orbitofrontal cortex (y = 40) related to the encoding of overlapping stimuli (OL sample > NOL sample). B. fMRI activity in the orbitofrontal cortex (y = 42) during the maintenance of overlapping stimuli across a short delay period (OL delay > NOL delay). C. Activations in orbitofrontal cortex bilaterally (OFC; yellow circles) and the right hippocampus (green circle) during the successful retrieval of overlapping stimuli in working memory (OL Match > NOL Match). Displayed slices are from y = 34. For display purposes the statistical parametric map is shown superimposed on a single participant’s anatomic image (p = 0.01 with 88 contiguous voxels). R = right hemisphere.

Table 1.

Activity during encoding and maintenance of overlapping stimuli

| Brain region | kE | side | t | coordinate | z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overlapping sample > non-overlapping sample | |||||

| orbitofrontal cortex (BA 47/12) | 90 | R | 3.80 | 44,40,−10 | 3.16 |

| Non-overlapping sample > overlapping sample | |||||

| superior frontal gyrus (BA 8) | 808 | L | 5.19 | −14,44,48 | 3.92 |

| superior frontal gyrus (BA 9) | L | 3.98 | −16,56,20 | 3.27 | |

| anterior cingulate cortex (BA 32) | L | 3.97 | −8,52,14 | 3.27 | |

| calcarine sulcus (BA 17) | 260 | L | 4.01 | −16,−98,−4 | 3.29 |

| calcarine sulcus (BA 17) | 249 | R | 3.95 | 14,−90,2 | 3.25 |

| precuneus (7p) | 148 | L | 3.22 | −6,−60,26 | 2.78 |

| Overlapping delay > non-overlapping delay | |||||

| putamen | 115 | L | 4.08 | −22,10,−8 | 3.33 |

| caudate | L | 3.48 | −16,20,0 | 2.96 | |

| inferior temporal gyrus (BA 21) | 142 | R | 3.75 | −52,−50,−8 | 3.13 |

| orbitofrontal cortex (BA 11L) | 110 | R | 3.13 | 32,42,−4 | 2.72 |

kE = cluster size in voxels. Regions active within the same cluster are grouped together.

L, left; R, right; BA = Brodmann area. t and z values are for the peak voxel.

Coordinates in MNI space.

Maintenance of overlapping stimuli in working memory

Brain regions responsible for maintaining overlapping representations of the same individual shown with two different facial expressions across a delay during working memory were identified by contrasting the OL and NOL delay regressors. This analysis revealed significant activation in right lateral orbitofrontal cortex (xyz = 32, 42, −4), in what Ongur and colleagues (2003) define as Brodmann area (BA) 11L (Fig. 3B). Additionally, the left dorsal striatum, including both the putamen (xyz = −22, 10, −8) and caudate (xyz = −16, 20, 0) as well as the inferior temporal gyrus (IT) (xyz = −52, −50, −8) show increased fMRI activity in the delay period of the OL condition compared to the NOL condition (Table 1).

Retrieval of overlapping stimuli in working memory

Brain regions active during the successful retrieval of an overlapping representation of an individual seen with two different facial expressions was determined by contrasting overlapping match trials with non-overlapping match trials (Table 2). Significant fMRI activity was found in multiple parts of the lateral orbitofrontal cortex including bilateral activity in Brodmann area 11L (left hemisphere xyz = −30, −32, −18; right hemisphere xyz = 30, 34, −14) and in Brodmann area 47/12 (left hemisphere xyz = −54, 34, −2; right hemisphere xyz = 46, 34, 0). Additionally, the posterior hippocampus showed bilateral activation (left hemisphere xyz = −32, −36, −8; right hemisphere xyz = 22, −40, −2) when participants successfully retrieved an overlapping stimulus (OL match vs. NOL match; Fig. 3C).

Table 2.

Activity when retrieving overlapping stimuli in working memory

| Brain region | kE | side | t | coordinate | z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overlapping match > non-overlapping match trials | |||||

| fusiform gyrus (BA 37) | 27972 | L | 6.68 | −34,−42,−14 | 4.55 |

| fusiform gyrus (BA 37) | R | 5.38 | 42,−42,−18 | 4.01 | |

| orbitofrontal cortex (BA 11L) | L | 3.48 | −30,32,−18 | 2.96 | |

| orbitofrontal cortex (BA 47/12) | L | 3.49 | −54,34,−2 | 2.96 | |

| hippocampus | R | 5.19 | 22,−40,−2 | 3.92 | |

| hippocampus | L | 5.27 | −32,−36,−8 | 3.95 | |

| dorsal striatum | R | 3.75 | 10,8,0 | 3.13 | |

| dorsal striatum | L | 3.32 | −8,6,0 | 2.85 | |

| calcarine fissure (BA 17) | R | 6.43 | 30,−74,6 | 4.46 | |

| intraparietal sulcus | L | 5.37 | −26,−60,34 | 4.00 | |

| intraparietal sulcus | R | 3.93 | 26,−60,34 | 3.25 | |

| anterior cingulate cortex (BA 24) | L | 5.00 | −2,28,46 | 3.82 | |

| anterior cingulate cortex (BA 24) | R | 4.74 | 10,18,40 | 3.69 | |

| ventral lateral prefrontal cortex (BA 45) | L | 4.60 | −46,18,20 | 3.62 | |

| dorsal lateral prefrontal cortex (BA 9/46) | L | 4.81 | −50,22,28 | 3.73 | |

| superior frontal gyrus (BA 8) | R | 4.89 | 2,32,54 | 3.77 | |

| superior frontal gyrus (BA 8) | L | 4.24 | −4,22,60 | 3.42 | |

| middle frontal gyrus (BA 6) | L | 4.18 | −36,0,42 | 3.39 | |

| lingual gyrus (BA 18) | R | 3.20 | 16,−72,6 | 2.77 | |

| thalamus | R | 5.90 | 10,−24,12 | 4.24 | |

| thalamus | L | 4.59 | −6,−30,0 | 3.61 | |

| anterior insula | L | 5.62 | −36,20,−10 | 4.12 | |

| inferior temporal gyrus (BA 19) | R | 5.54 | 46,−60,−6 | 4.08 | |

| lateral occipital gyrus (BA 18) | R | 5.25 | 24,−90,−4 | 3.95 | |

| cerebellum | R | 5.75 | 28,−72,−46 | 4.17 | |

| cerebellum | R | 5.68 | 10,−72,−24 | 4.14 | |

| cerebellum | R | 5.56 | 14,−50,−18 | 4.09 | |

| cerebellum | L | 3.99 | −6,−58,−20 | 3.28 | |

| cerebellum | L | 6.39 | −2,−70,−22 | 4.46 | |

| midbrain | L | 5.24 | −4,−24,−10 | 3.94 | |

| orbitofrontal cortex (BA 11L) | 532 | R | 4.45 | 30,34,−14 | 3.54 |

| orbitofrontal cortex (BA 47/12) | R | 3.65 | 46,34,0 | 3.08 | |

| anterior insula | R | 4.11 | 46,22,−12 | 3.35 | |

| dorsal lateral prefrontal cortex (BA 9/46) | 807 | R | 5.59 | 50,26,26 | 4.11 |

| middle frontal gyrus (BA 6) | 132 | L | 5.10 | −40,2,58 | 3.87 |

| middle frontal gyrus (BA 6) | 111 | R | 4.15 | 44,0,58 | 3.37 |

kE = cluster size in voxels. Regions active within the same cluster are grouped together.

L, left; R, right; BA = Brodmann area. t and z values are for the peak voxel.

Coordinates in MNI space.

Comparison of non-overlapping to overlapping condition

We directly contrasted the non-overlapping condition to the overlapping condition at sample, delay and test to examine brain regions showing more activation when encoding, maintaining and retrieving two different faces with two different emotional expressions compared to when the same face was shown twice with different emotional expressions. There were significant activations when comparing the non-overlapping to overlapping condition in the sample period of the task and included primary visual cortex (left hemisphere xyz = 14, −90, 2; right hemisphere xyz = −4, −92, 4) as well as left superior frontal gyrus (xyz = −16, 56, 20) and left anterior cingulate cortex (xyz = −8, 52, 14; Table 1). At delay and for test match trials, no brain regions showed more fMRI activity in the non-overlapping condition compared to the overlapping condition.

Functional Connectivity Results

Region of interest results

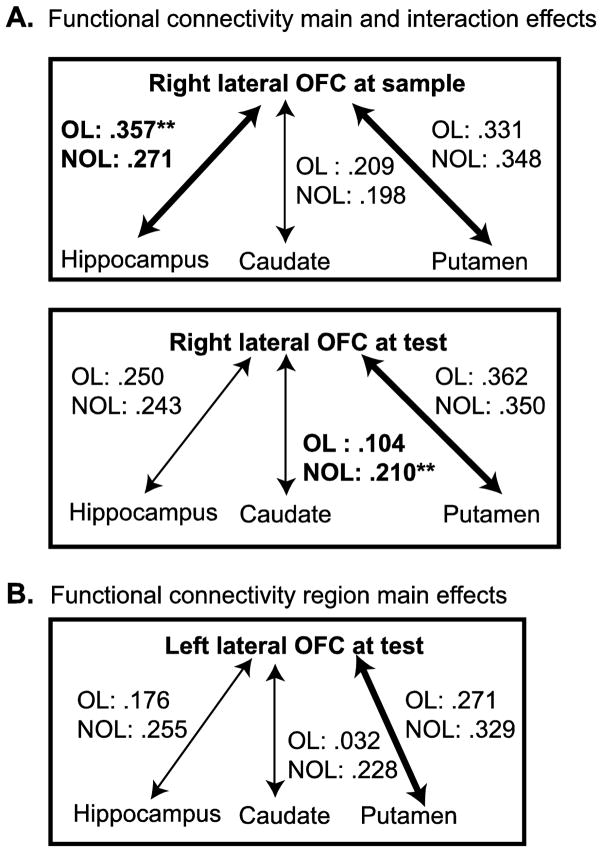

Orbitofrontal-hippocampal functional connectivity during encoding of overlapping stimuli

The results of a 2 x 2 x 3 repeated measures ANOVA with condition (overlapping and non-overlapping), hemisphere (right and left) and region (hippocampus, caudate, and putamen) on the extracted correlational map z-scores at sample showed a significant main effect of region (F(2,30) = 8.154, p ≤ 0.001) and a significant condition x region interaction (F(2,30) = 4.330, p ≤ 0.05). Pairwise comparisons relating to the main effect of region showed that collapsing condition and hemisphere, the orbitofrontal cortex was more strongly functionally connected to the hippocampus than the caudate (OFC-hippocampus mean ± S.E.M z = 2.109 ± 0.39 vs. OFC-caudate z = 1.327 ± 0.28, p ≤ 0.05) and was more strongly functionally connected to the putamen than the caudate (OFC-putamen z = 2.292 ± 0.35 vs. OFC-caudate z = 1.327 ± 0.28, p ≤ 0.05). To further explore the significant condition x region interaction, three paired sample t-tests were run directly comparing functional connectivity in the overlapping to the non-overlapping condition in the hippocampus, caudate and putamen collapsing hemisphere. Only three paired sample t-tests were run because we were interested in directly comparing the overlapping and non-overlapping condition within the same brain region. The results of these paired sample t-tests showed a significantly higher z-score only for orbitofrontal connectivity to the hippocampus during the overlapping condition compared to the non-overlapping condition (t(15) = 2.2, p ≤ 0.05; OFC-hippocampus overlapping z = 2.35 ± 0.32, OFC-hippocampus non-overlapping z = 1.86 ± 0.39). A higher z-score for the overlapping compared to the non-overlapping condition suggests that when encoding overlapping stimuli, activity in the orbitofrontal cortex and hippocampus is more tightly correlated.

Orbitofrontal cortical functional connectivity differences during test match trials

Two individual 2 x 2 x 3 repeated measures ANOVAs, one for the right and left lateral orbitofrontal cortical correlation z-scores, with condition, hemisphere and region (hippocampus, caudate, putamen) as factors were conducted to assess functional connectivity differences during match trials at test. The 2 x 2 x 3 ANOVA examining z-score differences with the right lateral orbitofrontal cortex showed a significant main effect of region (F(2,30) = 15.208, p ≤ 0.001) and a significant condition x region interaction (F(2,30) = 4.624, p ≤ 0.05). The main effect of region was caused by significantly higher z-scores for connectivity between the right lateral orbitofrontal cortex and the putamen compared to the hippocampus (right lateral OFC-putamen z = 1.71 ± 0.22 vs. right lateral OFC-hippocampus z = 1.15 ± 0.15, p ≤ 0.01) and the putamen compared to the caudate (right lateral OFC-putamen z = 1.71 ± 0.22 vs. right lateral OFC-caudate z = 0.74 ± 0.22, p ≤ 0.001) collapsing across condition and hemisphere. Three paired sample t-tests were run to directly compare correlation z-scores between the overlapping and non-overlapping condition within the hippocampus, caudate and putamen collapsing across hemisphere. Only the caudate-right lateral OFC connectivity showed a significant difference between the overlapping (overlapping z = 0.4829 ± 0.27) and non-overlapping condition (non-overlapping z = 0.9989 ± 0.22; t(15) = 2.143, p ≤ 0.05). The greater correlation z-score for the non-overlapping condition suggests that the right lateral orbitofrontal cortex was more tightly correlated with caudate functioning during non-overlapping test match trials.

There was also a significant main effect of region in the left lateral orbitofrontal cortex (F(2,30) = 9.977, p ≤ 0.001) during the test period though no significant condition x region interaction was found. As with the right lateral orbitofrontal cortex, the left lateral orbitofrontal cortex showed more functional connectivity with the putamen (z = 1.42 ± 0.18) than the hippocampus (z = 1.04 ± 0.23) and caudate (z = 0.60 ± 0.18) collapsing across condition and hemisphere.

Whole brain functional connectivity results

We examined whole brain functional connectivity differences by directly contrasting the z-maps from the beta series correlation analysis corresponding to the correlation between the overlapping and non-overlapping conditions. We used the same p < 0.01 voxel threshold corrected for multiple comparisons with a cluster extent of 88 voxels that was used in the univariate analysis. The results of these contrasts can be viewed in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Whole brain functional connectivity with orbitofrontal cortex

| Brain region | kE | side | t | coordinate | z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overlapping sample > non-overlapping sample (44, 40, −10) | |||||

| posterior cingulate cortex (BA 23) | 481 | L | 5.00 | −14,−60,22 | 3.78 |

| posterior cingulate cortex (BA 23) | R | 4.67 | 12,−54,24 | 3.61 | |

| Non-overlapping delay > overlapping delay (32, 42, −4) | |||||

| posterior cingulate cortex (BA 31) | 597 | R | 5.88 | 14,−18,48 | 4.17 |

| parahippocampal cortex | 114 | R | 4.65 | 34,−40,−10 | 3.6 |

| post-central gyrus | 323 | R | 3.56 | 36,−40,62 | 2.99 |

kE = cluster size in voxels. Regions active within the same cluster are grouped together.

L, left; R, right; BA = Brodmann area. t and z values are for the peak voxel.

Coordinates in MNI space.

Table 4.

Lateral orbitofrontal functional connectivity at test

| Brain region | kE | side | t | coordinate | z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-overlapping match > overlapping match test trials (−46, 34, 0) | |||||

| retrosplenial cortex | 1013 | L | 6.36 | −28,−72,6 | 4.37 |

| superior temporal gyrus (BA 22) | L | 4.79 | −46,−40,14 | 3.67 | |

| hippocampus | L | 4.46 | −36,−20,−18 | 3.50 | |

| hippocampus | L | 4.32 | −34,−34,−4 | 3.43 | |

| cuneus (BA 19) | 382 | L | 5.28 | −6,−90,32 | 3.91 |

| cuneus (BA 19) | R | 4.24 | 6,−8,34 | 3.38 | |

| parietal-occipital sulcus | R | 4.16 | 4,−66,24 | 3.34 | |

| cuneus (BA 18) | L | 3.26 | −6,−100,10 | 2.79 | |

| para-central gyrus | 356 | R | 4.86 | 8,−30,60 | 3.71 |

| para-central gyrus | L | 3.88 | −12,−36,62 | 3.18 | |

| post-central gyrus | L | 3.70 | −16,−34,64 | 3.07 | |

| dorsal striatum | 431 | R | 4.02 | 22,18,20 | 3.26 |

| dorsal striatum | 172 | L | 3.77 | −14,20,16 | 3.11 |

| hippocampus | 133 | R | 3.96 | 38,−30,−10 | 3.23 |

| insula | 136 | R | 3.69 | 32,−12,18 | 3.06 |

| retrosplenial cortex | 106 | L | 3.10 | −10,−50,4 | 2.68 |

| Non-overlapping match > overlapping match test trials (46, 34, 0) | |||||

| ventral lateral prefrontal cortex (BA 44) | 1623 | L | 6.93 | −60,−2,16 | 4.57 |

| insula | L | 6.27 | −44,−14,4 | 4.33 | |

| pre-central gyrus | L | 4.94 | −58,−8,24 | 3.75 | |

| superior temporal gyrus (BA 22) | L | 4.93 | −52,−24,6 | 3.74 | |

| ventral lateral prefrontal cortex (BA 44) | 1544 | R | 5.08 | 64,−2,18 | 3.81 |

| insula | R | 4.84 | 40,−18,18 | 3.70 | |

| superior temporal gyrus (BA 22) | R | 4.49 | 50,−20,6 | 3.52 | |

| pre-central gyrus | R | 4.33 | 58,−2,14 | 3.43 | |

| hippocampus | 92 | L | 5.06 | −32,−32,−6 | 3.80 |

| hippocampus | 100 | R | 3.50 | 36,−38,−2 | 2.95 |

| angular gyrus (BA 39) | 96 | L | 4.24 | −58,−58,22 | 3.39 |

| angular gyrus (BA 39) | 142 | R | 3.98 | 42,−52,18 | 3.24 |

| medial rostral prefrontal cortex (BA 10) | 249 | L | 6.71 | −20,46,2 | 4,49 |

kE = cluster size in voxels. Regions active within the same cluster are grouped together.

L, left; R, right; BA = Brodmann area. t and z values are for the peak voxel.

Coordinates in MNI space.

At sample, the right lateral orbitofrontal cortex (44, 40, −10) showed stronger functional connectivity with the posterior cingulate cortex during the overlapping compared to non-overlapping condition (Table 3). Other significant differences in orbitofrontal cortical functional connectivity were in the comparisons of the non-overlapping to the overlapping condition at delay and test. During the delay, the right lateral orbitofrontal cortex (32, 42, −4) showed stronger functional connectivity with the posterior cingulate cortex, parahippocampal cortex, and post-central gyrus in the non-overlapping condition compared to the overlapping condition (Table 3).

Differential functional connectivity with the right and left lateral orbitofrontal cortex (±46, 34, 0) during non-overlapping compared to overlapping match trials at test can be seen in Table 4. Among other regions, the left lateral orbitofrontal cortex showed stronger functional connectivity with the hippocampus bilaterally, the dorsal striatum bilaterally and the left retrosplenial cortex during non-overlapping match trials at test. The right lateral orbitofrontal cortex was also more strongly connected to the hippocampus bilaterally as well as the ventral lateral prefrontal cortex (BA 44) and angular gyrus (BA 39) bilaterally during non-overlapping match trials at test (Table 4).

Discussion

We contrasted fMRI activity and orbitofrontal cortical functional connectivity while participants encoded, maintained and retrieved representations of the same individual shown with two different facial expressions (overlapping condition, OL) with fMRI activity and orbitofrontal cortical functional connectivity while participants encoded, maintained and retrieved pictures of two different individuals with two different facial expressions (non-overlapping condition, NOL) in a delayed match-to-sample task (DMS). There was significant right lateral orbitofrontal cortex (BA 47/12) activity during the sample phase and right lateral orbitofrontal cortex (BA 11L) activity during the delay phase when participants had to encode overlapping face stimuli and maintain disambiguated face representations across a short delay (Fig. 3A and 3B). There was also stronger functional connectivity between the right lateral orbitofrontal cortex and the hippocampus at sample when encoding overlapping face stimuli compared to non-overlapping face stimuli (Fig. 4). Additionally, both the orbitofrontal cortex and hippocampus showed greater fMRI activity in the test phase of the overlapping condition compared to the non-overlapping condition (Fig. 3C).

Figure 4.

Summary of functional connectivity between lateral orbitofrontal cortex and the hippocampus, caudate and putamen regions of interest. The r value of the correlation between the orbitofrontal cortex and each region of interest for the overlapping (OL) and non-overlapping (NOL) conditions are reported. A. At sample (top), right lateral orbitofrontal-hippocampal functional connectivity at sample was stronger during the overlapping compared to the non-overlapping condition (indicated by **). The putamen and hippocampus were more strongly connected to the orbitofrontal cortex collapsing across condition (thickened arrows). At test (bottom), right lateral orbitofrontal-caudate functional connectivity was stronger during the non-overlapping condition compared to the overlapping condition (indicated by **) though the putamen showed the strongest functional connectivity with the orbitofrontal cortex when collapsing across condition (thickened arrow). B. The left lateral orbitofrontal cortex was more strongly functional connected to the putamen when collapsing across condition (thickened arrow).

Interestingly, though the hippocampus and orbitofrontal cortex showed increased fMRI activity for match trials at test in the overlapping condition, the lateral orbitofrontal cortex was more strongly functionally connected to the hippocampus, parahippocampal cortex, fusiform gyrus and striatum during non-overlapping compared to overlapping test match trials (Table 4). In the non-overlapping condition, two different individuals were shown at sample, each with a different facial expression. At test, the participants needed to determine which one of the two sample identities the test face matched suggesting the increased orbitofrontal functional connectivity for non-overlapping test match trials is due to retrieving two different identities compared to only one identity in the overlapping condition.

These results have multiple implications for how social cues like face identity and emotional expression are encoded, maintained and retrieved in working memory.When encountering the same familiar individual multiple times with different social cues, such as facial expression, the right lateral orbitofrontal cortex and hippocampus are more strongly recruited and show stronger functional connectivity when disambiguating each encounter with that individual. Disambiguating each encounter with the same individual ensures the correct social cue is used to select the appropriate response and to guide behavior during subsequent encounters. The right lateral orbitofrontal cortex and striatum show increased recruitment during the delay period after encountering the same individual with two different facial expressions (Fig. 3B, Table 1) suggesting these regions play a role in maintaining overlapping stimuli. When re-encountering the same individual previously seen with two different social cues, the lateral orbitofrontal cortex, along with the hippocampus and fusiform gyrus bilaterally show increased fMRI activity (Fig. 3C, Table 2) suggesting these regions contribute to the retrieval of the correct previous encounter with that individual.

Orbitofrontal cortex and the encoding, maintenance and retrieval of overlapping stimuli

The orbitofrontal cortex may contribute to memory by working with the hippocampus to separate when the same or overlapping stimuli have been experienced. The hippocampus sends anatomic projections to the orbitofrontal cortex (Barbas and Blatt, 1995; Cavada et al., 2000; Insausti and Munoz, 2001; Roberts et al., 2007) providing the anatomical framework for a concerted engagement of these two regions in memory processes. Two recent studies suggest that the hippocampus and orbitofrontal cortex work together during the disambiguation of overlapping sequences in long term memory (Brown et al., 2012; Ross et al., 2011). The current study shows increased orbitofrontal cortical activity during the sample, delay and test phases of a working memory task where participants were asked to disambiguate two overlapping social stimuli. Importantly, the current study also shows the right lateral orbitofrontal cortex works with the hippocampus when encoding overlapping stimuli in a working memory task. These results suggest that the orbitofrontal cortex interacts with the hippocampus to create separate representations of overlapping stimuli during the encoding phase of a working memory task and that the orbitofrontal cortex contributes to the maintenance and retrieval of overlapping stimuli.

One way the orbitofrontal cortex may contribute to separating, or disambiguating, overlapping stimuli is to assist the hippocampus in linking each stimulus exposure to the specific context in which it was experienced. The orbitofrontal cortex is more strongly activated (Brown et al., 2010) and shows stronger functional connectivity (Brown et al, 2012; Ross et al., 2011) at choice points when contextual information is needed to guide decision making. Damage to the orbitofrontal cortex impairs the ability of monkeys to correctly learn the specific reward value of a repeatedly presented stimulus in any singular trial and causes response strategies to shift to a more probabilistic strategy (Walton et al., 2010). The inability to learn the specific reward value of a repeated stimulus in any one trial suggests an inability to disambiguate each encounter. Additionally, the orbitofrontal cortex is critical for making correct decisions in reversal learning tasks (Berlin et al., 2004; Chudasama and Robbins, 2003; Fellows and Farah, 2003; Hornak et al., 2004; McAlonan and Brown, 2003; Meunier et al., 1997; Rudebeck and Murray, 2008; Schoenbaum et al., 2003; Tsuchida et al., 2010). After reversal, the reward contingencies change where the previously rewarded stimulus becomes unrewarded and the previously unrewarded stimulus becomes rewarded. Importantly, the earlier stimulus-outcome associations still exist after the reversal, creating overlapping representations which need to be disambiguated. Both monkeys (Rudebeck and Murray, 2008) and humans (Tsuchida et al., 2010) with orbitofrontal cortex damage make more mistakes post-reversal because they are more likely to switch their response after a rewarded trial to the previous reward contingency. Switching back to the old response contingency after orbitofrontal cortex damage suggests an inability to disambiguate the current reward contingency from prior contingencies. Therefore, we suggest a critical function of the orbitofrontal cortex during both long-term and working memory tasks is to assist in resolving interference caused by overlapping representations by linking each encounter with a stimulus to the context in which it appeared.

In the current study, we show increased fMRI activity in the right lateral orbitofrontal cortex and increased functional connectivity with the hippocampus when encoding two overlapping social stimuli. Specifically, when the participant was shown two pictures of the same individual with different social cues (facial expressions), the right lateral orbitofrontal cortex and hippocampus were more strongly functionally connected than when viewing two pictures of two different individuals with different social cues. Viewing the same individual with different facial expressions creates interference between the two encounters with the individual. In order to correctly indicate whether the test face matched the first or second stimulus viewed at sample in the overlapping condition, the participants would have needed to separate the two social cues (for example, happy face vs. sad face). Our results show that the orbitofrontal cortex and hippocampus work together when encoding the specific instance of encountering the same individual. We suggest the ability to separate different encounters with the same individual seen with different social cues allows for appropriate social interactions. For example, if a person is first seen as happy and then seen as sad, the appropriate social response would change. We propose that the orbitofrontal cortex and hippocampus are part of a working memory system as well as a long-term memory system that allows us to flexibly encode separate representations of an individual in the varying social contexts in which we encounter them.

The hippocampus and the retrieval of overlapping stimuli in working memory

In order to correctly indicate whether the test stimulus matched the first or second stimulus shown in the sample period of the overlapping condition, participants needed to disambiguate overlapping representations (two different facial expressions) of a single individual. The hippocampus has been shown to be important for disambiguating, or separating, overlapping sequences (Agster et al., 2002; Kumaran and Maguire, 2006; Ross et al., 2009) and overlapping navigational routes (Brown et al., 2010; Wood et al., 2000) during long-term memory. Our results show that in the test phase of a DMS task, the hippocampus has stronger fMRI activity when retrieving a single face identity shown with two different facial expressions compared to the retrieval of two different face identities shown with two different facial expressions. The data extend previous work by suggesting the hippocampus contributes to working memory when retrieving representations of overlapping stimuli.

Contrary to our predictions, we did not see differential hippocampal fMRI activity during the encoding or maintenance of overlapping representations of the same individual. It may be that the current whole brain scanning protocol lacked the necessary resolution to detect disambiguation related hippocampal activity during encoding and maintenance. In support of this idea, recent work in our laboratory using the same paradigm with high resolution fMRI focused on the medial temporal lobes shows hippocampal activity differences at encoding and maintenance at the subfield level. Specifically, in that study we observed greater hippocampal activity in CA3/dentate gyrus and CA1 during encoding and CA1 and the subiculum during the delay period of the overlapping condition compared to the non-overlapping condition (Newmark et al., 2013) suggesting a role for the hippocampus when encoding overlapping stimuli and when maintaining disambiguated stimuli in working memory.

It has recently been suggested that the hippocampus plays a role in working memory, though the nature of hippocampal involvement in working memory is under debate. Some researchers suggest the hippocampus is only involved when the capacity of working memory has been exceeded resulting in the engagement of long-term memory processes in short-term memory tasks (Jeneson et al., 2010; Shrager et al., 2008). Other research has suggested the hippocampus contributes to working memory in a process specific manner. The hippocampus has been associated with long-term relational memory (Eichenbaum, 2000). In addition, neuropsychological experiments in human amnesic patients have shown that the hippocampus is critical to remembering relational information also over short delay periods (Finke et al., 2008; Hannula et al., 2006; Nichols et al., 2006; Olson et al., 2006a,b). The current results show increased hippocampal activity in the test phase of a working memory task where disambiguating overlapping stimuli and maintaining disambiguated representations over a brief delay is critical to task performance. Together with prior studies showing hippocampal involvement in the disambiguation of long-term memories (Agster et al., 2002; Brown et al., 2010; Kumaran and Maguire, 2006; Ross et al., 2009; Wood et al., 2000) and a recent high resolution fMRI study showing hippocampal activation during encoding and maintenance using the same task reported here (Newmark et al., 2013), our results provide evidence suggesting that disambiguation related activity associated with hippocampal function is not dependent on the amount of time the information is to be remembered, and is present in both long-term and working, i.e. short-term memory paradigms. This is critical for processing social cues as they are dynamic and can change rapidly requiring a mechanism by which individual encounters with an individual can be segregated so that appropriate behavioral responses can be selected in subsequent interactions.

Orbitofrontal cortical functional connectivity during test match trials

During match trials of the non-overlapping condition, the lateral orbitofrontal cortex showed stronger functional connectivity with many brain regions including the hippocampus, retrosplenial cortex and fusiform gyrus compared to overlapping match trials. Unlike the overlapping condition, where the same person was shown with two different facial expressions during the sample period, the non-overlapping condition had two different individuals with two different facial expressions presented at sample. Therefore, the differences in orbitofrontal cortical functionally connectivity at test between the non-overlapping and overlapping condition could be related to viewing two different identities at sample suggesting the increased functional connectivity may have been related to a load effect. The hippocampus and retrosplenial cortex show increased fMRI activity in the retrieval phase of a working memory task with increased load (Schon et al., 2009). In the current study, the hippocampus may act as a match/mis-match detector (Kumaran and Maquire, 2006, 2007) indicating that the test stimulus matched a previously viewed stimulus. The increased functional connectivity between the orbitofrontal cortex and the hippocampus, retrosplenial cortex and fusiform gyrus may then be caused by the participant retrieving two face identities from the sample in order to determine which one the test face matched.

The current study may not show increased fMRI activity in the non-overlapping condition due to the interference inherent in viewing overlapping stimuli where more processing resources might be needed to determine which specific sample stimulus matched the test stimulus. In the overlapping condition, the hippocampus would have also indicated a match was present, but due to the interference inherent in viewing overlapping stimuli, more processing resources were needed to determine which specific sample stimulus matched the test stimulus. The load effect for the non-overlapping stimuli and the interference in the overlapping condition may explain why there was increased functional connectivity between the orbitofrontal cortex, hippocampus, retrosplenial and fusiform at test for the non-overlapping condition but increased fMRI activity during overlapping trials in these brain regions. It is important to note that the orbitofrontal cortical functional connectivity at test reported here is a result of a contrast between the non-overlapping and overlapping condition connectivity profiles. The results do not imply that there is no functional connectivity between the orbitofrontal cortex and these other brain regions in the overlapping condition, simply that the functional connectivity is stronger when matching a test stimulus in the non-overlapping condition.

Conclusion

Combined with prior studies, our results suggest the hippocampus and orbitofrontal cortex play a role in both working memory and long term memory when separate representations of overlapping stimuli need to be disambiguated. In addition, we suggest this ability to disambiguate overlapping representations is important for social interactions where the orbitofrontal cortex and hippocampus play key roles in enabling us to flexibly encode and distinguish between changing contexts and social situations, so that we may act appropriately.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation Science of Learning Center (grant number SMA-0835976), National Institutes of Health (grant number P50 MH071702) and by the Department of Psychology at Boston University. Functional magnetic resonance imaging conducted at the Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging at the Massachusetts General Hospital, using resources provided by the Center for Functional Neuroimaging Technologies, P41RR14075, a P41 Regional Resource supported by the Biomedical Technology Program of the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), National Institutes of Health. This work also involved the use of instrumentation supported by the NCRR Shared Instrumentation Grant Program and High-End Instrumentation Grant Program; specifically, grant number S10RR021110. We thank Matthew Grace for his assistance developing and piloting the behavioral task, and Dr. Michael Hasselmo and Dr. David Somers for helpful discussions about the study. We also thank Dr. Ruben Gur’s Brain Behavior Laboratory at the University of Pennsylvania for supplying the majority of the face stimuli used in this study.

References

- Agster KL, Fortin NJ, Eichenbaum H. The hippocampus and disambiguation of overlapping sequences. J Neurosci. 2002;22(13):5760–5768. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05760.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axmacher N, Elger CE, Fell J. Working memory-related hippocampal deactivation interferes with long-term memory formation. J Neurosci. 2009;29(4):1052–1960. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5277-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbas H, Blatt GJ. Topographically specific hippocampal projections target functionally distinct prefrontal areas in the rhesus monkey. Hippocampus. 1995;5:511–533. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450050604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin HA, Rolls ET, Kischka U. Impulsivity, time perception, emotion and reinforcement sensitivity in patients with orbitofrontal cortex lesions. Brain. 2004;127(Pt 5):1108–1126. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bower MR, Euston DR, McNaughton BL. Sequential-context-dependent hippocampal activity is not necessary to learn sequences with repeated elements. J Neurosci. 2005;25(6):1313–1323. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2901-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boynton GM, Engel SA, Glover GH, Heeger DJ. Linear systems analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging in human V1. J Neurosci. 1996;16(13):4207–4221. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-13-04207.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TI, Ross RS, Keller JB, Hasselmo ME, Stern CE. Which way was I going? Contextual retrieval supports the disambiguation of well learned overlapping navigational routes. J Neurosci. 2010;30(21):7414–7422. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6021-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TI, Ross RS, Tobyne SM, Stern CE. Cooperative interactions between hippocampal and striatal systems support flexible navigation. Neuroimage. 2012;60:1316–1330. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan JB, McIntosh AR, De Rosa E. Two distinct functional networks for successful resolution of proactive interference. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17(7):1650–1663. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavada C, Company T, Tejedor J, Cruz-Rizzolo RJ, Reinoso-Suarez F. The anatomical connections of the macaque monkey orbitofrontal cortex. A review. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:220–242. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.3.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chudasama Y, Robbins TW. Dissociable contributions of the orbitofrontal and infralimbic cortex to pavlovian autoshaping and discrimination reversal learning: further evidence for the functional heterogeneity of the rodent frontal cortex. J Neurosci. 2003;23(25):8771–8780. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-25-08771.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney SM, Ungerleider LG, Keil K, Haxby JV. Object and spatial visual working memory activate separate neural systems in human cortex. Cereb Cortex. 1996;6:39–49. doi: 10.1093/cercor/6.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damasio H. Human brain anatomy in computerized images. 2. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H. A cortical-hippocampal system for declarative memory. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2000;1:41–50. doi: 10.1038/35036213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekman P, Friesen W. Pictures of facial affect. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Fellows LK, Farah MJ. Ventromedial frontal cortex mediates affective shifting in humans: evidence from a reversal learning paradigm. Brain. 2003;126(Pt 8):1830–1837. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finke C, Braun M, Ostendorf F, Lehmann TN, Hoffmann KT, Kopp U, Ploner CJ. The human hippocampal formation mediates short-term memory of colour-location associations. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46(2):614–623. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginther MR, Walsh DF, Ramus SJ. Hippocampal neurons encode different episodes in an overlapping sequence of odors task. J Neurosci. 2011;31(7):2706–2711. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3413-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur RC, Sara R, Hagendoorn M, Marom O, Hughett P, Macy L, et al. A method for obtaining 3-dimensional facial expressions and its standardization for use in neurocognitive studies. J Neurosci Methods. 2002;115(2):137–143. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannula DE, Tranel D, Cohen NJ. The long and the short of it: relational memory impairments in amnesia, even at short lags. J Neurosci. 2006;26(32):8352–8359. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5222-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley T, Bird CM, Chan D, Cipolotti L, Husain M, Vargha-Khadem F, Burgess N. The hippocampus is required for short-term topographical memory in humans. Hippocampus. 2007;17(1):34–48. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haxby JV, Petit L, Ungerleider LG, Courtney SM. Distinguishing the functional roles of multiple regions in distributed neural systems for visual working memory. Neuroimage. 2000;11:380–391. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornak J, O’Doherty J, Bramham J, Rolls ET, Morris RG, Bullock PR, Polkey CE. Reward-related reversal learning after surgical excisions in orbito-frontal or dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in humans. J Cogn Neurosci. 2004;16(3):463–478. doi: 10.1162/089892904322926791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insausti R, Munoz M. Cortical projections of the non-entorhinal hippocampal formation in the cynomolgus monkey (Macaca fascicularis) Eur J Neurosci. 2001;14(3):435–451. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeneson A, Mauldin KN, Squire LR. Intact working memory for relational information after medial temporal lobe damage. J Neurosci. 2010;30(41):13624–13629. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2895-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kringelbach ML, Rolls ET. Neural correlates of rapid reversal learning in a simple model of human social interaction. Neuroimage. 2003;20:1371–1383. doi: 10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00393-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumaran D, Maguire EA. The dynamics of hippocampal activation during encoding of overlapping sequences. Neuron. 2006;49(4):617–629. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumaran D, Maguire EA. Match-mismatch processes underlie human hippocampal responses to associative novelty. J Neurosci. 2007;27(32):8517–8524. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1677-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoPresti ML, Schon K, Tricarico MD, Swisher JD, Celone KA, Stern CE. Working memory for social cues recruits orbitofrontal cortex and amygdala: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study of delayed matching to sample for emotional expressions. J Neurosci. 2008;28(14):3718–3728. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0464-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons MJ, Akamatsu S, Kamachi M, Gyoba J. Coding Facial Expressions with Gabor Wavelets. Third IEEE Int’l Conference on Automatic Face and Gesture Recognition; Nara, Japan. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- McAlonan K, Brown VJ. Orbital prefrontal cortex mediates reversal learning and not attentional set shifting in the rat. Behav Brain Res. 2003;146(1–2):97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh AR, Grady CL, Haxby JV, Ungerleider LG, Horwitz B. Changes in limbic and prefrontal functional interactions in a working memory task for faces. Cereb Cortex. 1996;6(4):571–584. doi: 10.1093/cercor/6.4.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier M, Bachevalier J, Mishkin M. Effects of orbital frontal and anterior cingulate lesions on object and spatial memory in rhesus monkeys. Neuropsychologia. 1997;35(7):999–1015. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(97)00027-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newmark RE, Schon K, Ross RS, Stern CE. Contributions of the hippocampal subfields and entorhinal cortex to disambiguation during working memory. Hippocampus. 2013 doi: 10.1002/hipo.22106. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols EA, Kao YC, Verfaellie M, Gabrieli JD. Working memory and long-term memory for faces: Evidence from fMRI and global amnesia for involvement of the medial temporal lobes. Hippocampus. 2006;16(7):604–616. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen RK, Nichols EA, Chen J, Hunt JF, Glover GH, Gabrieli JD, Wagner AD. Performance-related sustained and anticipatory activity in human medial temporal lobe during delayed match-to-sample. J Neurosci. 2009;29(38):11880–11890. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2245-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson IR, Moore KS, Stark M, Chatterjee A. Visual working memory is impaired when the medial temporal lobe is damaged. J Cogn Neurosci. 2006a;18(7):1087–1097. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2006.18.7.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson IR, Page K, Moore KS, Chatterjee A, Verfaellie M. Working memory for conjunctions relies on the medial temporal lobe. J Neurosci. 2006b;26(17):4596–4601. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1923-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ongur D, Ferry AT, Price JL. Architectonic subdivision of the human orbital and medial prefrontal cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2003;460(3):425–449. doi: 10.1002/cne.10609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto T, Eichenbaum H. Complementary roles of the orbital prefrontal cortex and the perirhinal-entorhinal cortices in an odor-guided delayed-nonmatching-to-sample task. Behav Neurosci. 1992;106(5):762–775. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.106.5.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantic M, Valstar MF, Rademaker R, Maat L. Web-based database for facial expression analysis. IEEE Int’l Conference on Multimedia and Expo; Amsterdam, The Netherlands. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Petrides M. Lateral prefrontal cortex: architectonic and functional organization. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2005;360(1456):781–795. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganath C, Cohen MX, Brozinsky CJ. Working memory maintenance contributes to long-term memory formation: neural and behavioral evidence. J Cogn Neurosci. 2005;17(7):994–1010. doi: 10.1162/0898929054475118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganath C, D’Esposito M. Medial temporal lobe activity associated with active maintenance of novel information. Neuron. 2001;31(5):865–873. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00411-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rissman J, Gazzaley A, D’Esposito M. Measuring functional connectivity during distinct stages of a cognitive task. Neuroimage. 2004;23(2):752–763. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AC, Tomic DL, Parkinson CH, Roeling TA, Cutter DJ, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Forebrain connectivity of the prefrontal cortex in the marmoset monkey (Callithrix jacchus): an anterograde and retrograde tract-tracing study. J Comp Neurol. 2007;502:86–112. doi: 10.1002/cne.21300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls ET. The functions of the orbitofrontal cortex. Brain Cogn. 2004;55:11–29. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2626(03)00277-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls ET. The representation of information about faces in the temporal and frontal lobes. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45:124–143. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross RS, Brown TI, Stern CE. The retrieval of learned sequences engages the hippocampus: Evidence from fMRI. Hippocampus. 2009;19(9):790–799. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross RS, Sherrill KR, Stern CE. The hippocampus is functionally connected to the striatum and orbitofrontal cortex during context dependent decision making. Brain Res. 2011;1423:53–66. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudebeck PH, Murray EA. Amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex lesions differentially influence choices during object reversal learning. J Neurosci. 2008;28(33):8338–8343. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2272-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala JB, Rama P, Courtney SM. Functional topography of a distributed neural system for spatial and nonspatial information maintenance in working memory. Neuropsychologia. 2003;41:341–356. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(02)00166-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheperjans F, Eickhoff SB, Hömke L, Mohlberg H, Hermann K, Amunts K, Zilles K. Probabilistic maps, morphometry, and variability of cytoarchitectonic areas in the human superior parietal cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2008;18:2141–2157. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schluppeck D, Curtis CE, Glimcher PW, Heeger DJ. Sustained activity in topographic areas of human posterior parietal cortex during memory-guided saccades. J Neurosci. 2006;26(19):5098–5108. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5330-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenbaum G, Setlow B, Nugent SL, Saddoris MP, Gallagher M. Lesions of orbitofrontal cortex and basolateral amygdala complex disrupt acquisition of odor-guided discriminations and reversals. Learn Mem. 2003;10(2):129–140. doi: 10.1101/lm.55203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schon K, Atri A, Hasselmo ME, Tricarico MD, LoPresti ML, Stern CE. Scopolamine reduces persistent activity related to long-term encoding in the parahippocampal gyrus during delayed matching in humans. J Neurosci. 2005;25(40):9112–9123. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1982-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schon K, Hasselmo ME, Lopresti ML, Tricarico MD, Stern CE. Persistence of parahippocampal representation in the absence of stimulus input enhances long-term encoding: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study of subsequent memory after a delayed match-to-sample task. J Neurosci. 2004;24(49):11088–11097. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3807-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schon K, Ross RS, Hasselmo ME, Stern CE. Complementary roles of medial temporal lobes and mid-dorsolateral prefrontal cortex for working memory for novel and familiar trial-unique visual stimuli. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2012 doi: 10.1111/ejn.12062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schon K, Tinaz S, Somers DC, Stern CE. Delayed match to object or place: an event-related fMRI study of short-term stimulus maintenance and the role of stimulus pre-exposure. Neuroimage. 2008;39(2):857–872. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schon K, Quiroz YT, Hasselmo ME, Stern CE. Greater working memory load results in greater medial temporal activity at retrieval. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:2561–2571. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shohamy D, Wagner AD. Integrating memories in the human brain: hippocampal-midbrain encoding of overlapping events. Neuron. 2008;60(2):378–389. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrager Y, Levy DA, Hopkins RO, Squire LR. Working memory and the organization of brain systems. J Neurosci. 2008;28(18):4818–4822. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0710-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotnick SD, Moo LR, Segal JB, Hart J., Jr Distinct prefrontal cortex activity associated with item memory and source memory for visual shapes. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res. 2003;17(1):75–82. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6410(03)00082-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern CE, Sherman SJ, Kirchhoff BA, Hasselmo ME. Medial temporal and prefrontal contributions to working memory tasks with novel and familiar stimuli. Hippocampus. 2001;11(4):337–346. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]