Abstract

This study compared the correlates of HIV risk among men who have sex with men (MSM) with newly diagnosed versus previously known HIV infection among 5,148 MSM recruited using modified snowball sampling in 5 Peruvian cities. Participants, if age≥18 years and sex with a male in the previous 12 months, underwent standardized computer-assisted risk assessments and HIV and syphilis testing. Overall, 420 (8.2%) participants tested HIV seropositive, most of whom (89.8%) were unaware of their HIV status. Compared to those who knew themselves to be HIV-infected, multivariate logistic regression demonstrated that unprotected anal intercourse at last encounter [AOR=2.84 (95% CI 1.09–7.40)] and having an alcohol use disorder (AUD) [AOR=2.14 (95% CI 1.01–5.54)] were independently associated with a newly diagnosed HIV infection. Being unaware of being HIV-infected was associated with high-risk sexual behaviors and AUDs, both of which are amenable to behavioral and medication-assisted therapy interventions.

Keywords: HIV infection, alcohol use disorders, extended-release naltrexone, medication-assisted therapies, sexual risk, Peru, male homosexuality

Introduction

As the HIV/AIDS pandemic enters its fourth decade, HIV transmission in several parts of the world shows no sign of abating, particularly among vulnerable and stigmatized populations, including men who have sex with men (MSM). Despite recent significant progress in HIV prevention and treatment, the HIV/AIDS pandemic continues to grow among MSM worldwide (1). In addition to well-established prevention strategies, such as educating high-risk individuals to reduce numbers of partners and increase condom use, antiretroviral therapy (ART) as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) reduces the risk of primary HIV transmission among high-risk MSM by 44% (2) and ART provided as “treatment as prevention” early in the course of HIV infection reduces secondary HIV transmission by 96% among heterosexual couples (3) and may similarly reduce HIV transmission among MSM (4). Central to these new efforts, however, are effective HIV testing strategies that guide primary and secondary prevention efforts. Specifically, for secondary prevention efforts to work, individuals who are unaware that they are HIV-infected must first be promptly diagnosed, linked and retained in care, prescribed ART to benefit their own health, as well as to ultimately achieve viral suppression and reduce transmission to others. For such Seek, Test and Treat strategies to work, the first and most critical component is that a significant number of individuals undergo HIV testing and new infections are identified (5).

In Latin America, as well as in many other regions worldwide, approximately half of all new HIV infections are due to unprotected anal intercourse between men (6). Peru, a middle-income country with low (0.2%) overall HIV prevalence among the general population (7), is experiencing a concentrated epidemic among MSM. HIV prevalence has been reported to be as high as 22% in Lima (8, 9), where three quarters of Peru’s reported HIV cases reside (9). This concentrated epidemic is similar to high prevalence countries in sub-Saharan Africa. The epidemic among MSM has been associated with risky sexual behaviors, including sex work and unprotected sex, with illicit drug use and with previously acquired sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (10).

Alcohol use has been previously associated with HIV risk behaviors (11, 12) and poor HIV treatment outcomes (13), including delays in HIV diagnosis (14). Delays in diagnosis may increase the likelihood that infected individuals can transmit HIV, particularly while disinhibition occurs under the influence of alcohol, which may facilitate sexual risk-taking especially when in highly stigmatized settings. Moreover, alcohol consumption among some MSM may be centered around gay bars, i.e. places were alcohol is consumed by default and in the expectancies that people have associating alcohol and enhanced sexual pleasure (15, 16). Recent data suggest an extraordinarily high prevalence of alcohol use disorders (AUDs), defined as hazardous, harmful or dependent drinking, by the World Health Organization’s Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) (17), among Peruvian MSM, as well as an association with high risk behaviors (18). In addition to sexual risk behaviors, AUDs can negatively impact health and wellbeing. They are, however, amendable to behavioral interventions, as well as medical treatment including pharmacological therapies. Brief counseling or pharmacological treatments should then be offered by medical providers, depending on the severity of the underlying AUD.

The percentage of Peruvian MSM that have undergone HIV testing is currently unknown, in part due to problems estimating the proportion of MSM and the stigma associated with disclosure. Knowing one’s HIV status is particularly important, especially among those who are HIV-infected and may not know it, because only HIV-infected persons can transmit the virus to others. To improve our understanding of how a Seek, Test and Treat approach (5) would work in Peru, we drew from the largest biobehavioral survey of its kind to first assess the proportion of HIV-infected MSM who were aware and unaware of their status and then to examine the independent correlates of being unaware (i.e. newly diagnosed) of HIV seropositive status, especially with a detailed examination of the impact of alcohol and drug use.

Methods

A biobehavioral surveillance survey of 5,575 MSM was conducted between May and October 2011, by the Peruvian NGO Associacion Civil Impacta Salud y Educacion (Impacta). Using a modified snowball recruitment strategy (19), participants were recruited from metropolitan Lima and the cities of Ica, Iquitos, Piura and Pucallpa were eligible for the study if they were able to provide informed consent, 18 years of age or older, male at birth (male-to-female transgender participants were included) and reporting at least one male sexual partner in the previous 12 months. Interviews were overseen by trained research assistants in private rooms in community outreach sites, non-governmental organizations and mobile vans. The Institutional Review Boards of Impacta and Yale University approved the study.

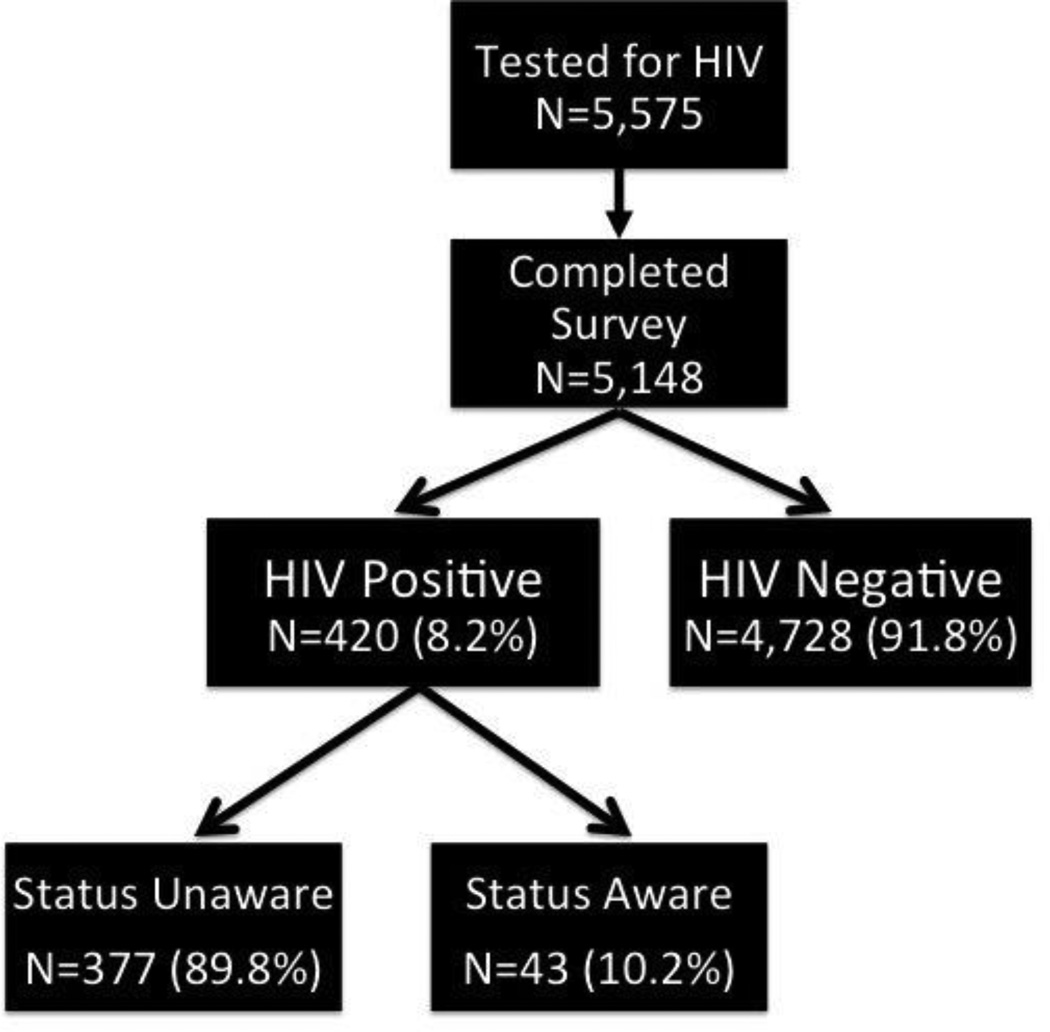

Following informed consent procedures, participants underwent HIV and syphilis counseling and testing and completed a 45- to 60-minute computer-assisted self-interview survey instrument with assistance from the research assistant if needed; 5,148 (92.3%) participants completed both testing and survey components and were included in the final analysis. The most common reason for not completing the survey was lack of time. Participants were subsequently reimbursed 10 Nuevos Soles (US $3.70) to cover transportation costs. HIV testing deployed the Determine HIV-1/2 Rapid Antibody Test (Abbott Diagnostics, Abbott Park, IL) with confirmatory Western Blot (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) testing. Syphilis was assayed using RPR (Organon Teknika, Durham, NC) and reactive tests were confirmed with MHA-TP (Organon Teknika, Durham, NC) to avoid false positives. Participants testing HIV seropositive were referred to clinics for appropriate care, including CD4 count and plasma HIV-1 RNA testing. Participants testing positive for syphilis were treated in accordance with Peruvian STI treatment guidelines, which follow 2006 US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Guidelines (20). Among the 5,148 study participants with complete data, 420 (8.2%) were found to be HIV-infected and served as the final analytic sample. See Figure 1 for study participant disposition.

Figure 1.

Disposition of Study Participants

A number of covariates were decided a priori to examine the association with the primary outcome, not being aware of being HIV-infected (i.e. newly diagnosed). Alcohol use disorders (AUDs) were identified using the World Health Organization’s 10-item Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) (17), a screening survey that is internationally accepted and validated for identifying alcohol dependence, as well as other alcohol use disorders with less severity (e.g. hazardous and harmful drinking); content and scoring of the AUDIT is widely available (21). According to accepted cutoffs, participants with AUDIT scores of ≥8 were classified as having an AUD. Additional cut-offs assessing more severe drinking problems were also assessed, but sample size for this level of disaggregation made analysis unfeasible. Syphilis diagnosis was based on having a RPR titer ≥1:16; this correlates with >90% likelihood of having an active infection (22). Sexual risk variables used were derived from the standardized “Alaska” criteria, which have been validated among MSM and independently correlated with incident HIV infections among Peruvian MSM. These 5 criteria include the following types of risk over the previous 6 months: 1) unprotected sex at last intercourse; 2) having had an STI; 3) having engaged in sex work; 4) having had more than 5 sexual partners; and 5) having an HIV+ sexual partner (23). Previous HIV testing was reported as ever or not; date of last HIV test was not recorded.

HIV infection was defined as being reactive by ELISA with confirmatory Western Blot testing. Being aware of being HIV-infected was defined by self-report; those who had never been HIV tested, self-reported themselves to be HIV negative or who did not know their HIV status were defined as being unaware of being HIV-infected – the dependent variable for this analysis – if they also had confirmed HIV infection.

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software package (version 19). For bivariate associations, chi-square and t-tests were used for categorical and continuous variables, respectively, while Mann-Whitney testing was used for non-normally distributed variables. Multivariate associations were examined using logistic regression. Bivariate associations where p<0.20 were included into the final multivariate model. Multiple models, including stepwise forward and stepwise backward elimination were used. Despite the multiple analytical approaches, we selected the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) assessing goodness-of-fit for all models and the best-fit model was ultimately selected (Table 2). Irrespective of which model used, the main significant outcomes from this analysis were unchanged except in magnitude of the association.

Table 2.

Multivariate Logistic Regression of Correlates Associated with Being Unaware of Being HIV-infected (N=420)

| Covariates | Multivariate Associations | |

|---|---|---|

| AOR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Unprotected sex with last partner | 2.84 (1.09 – 7.40) | 0.032 |

| Unprotected sex with any of last 3 partners | 1.24 (0.56 – 2.71) | 0.596 |

| Alcohol use disorder | 2.14 (1.01 – 4.54) | 0.048 |

| Syphilis infection | 0.52 (0.22 – 1.22) | 0.135 |

| Age | 0.97 (0.93 – 1.01) | 0.087 |

| AIC = 201.2 | ||

Legend: AOR=Adjusted Odds Ratio; AIC=Akaike Information Criterion

Results

Of the 5,148 total study participants with complete data, 420 (8.2%) had confirmed HIV infection. Of these 420 participants, 43 (10.2%) knew themselves to be HIV-infected. Thus, 377 participants or 89.8% of all HIV seropositive participants were unaware of being HIV-infected (Figure 1).

The risk behaviors and characteristics of the 420 HIV-infected MSM are presented in Table 2, with comparisons between those who were aware or unaware of their HIV seropositive status. Overall, high percentages of these HIV-infected men engaged in considerable HIV risk in the previous six months, including unprotected anal intercourse with their last (35.2%) or any of their last three sexual partners (37.9%), engagement in sex work (40.2%), having had more than five sexual partners (47.1%), having been recently diagnosed with a STI (23.1%) and having sex with a known HIV-infected partner (8.8%). Untreated syphilis (19.0%) was also exceedingly high among HIV seropositives, including those with known HIV serostatus (26.8%). These men also had a high prevalence of underlying AUDs (55.2%) or had used drugs (13.3%) in the previous 3 months.

After controlling for several potential confounders, the final multivariate logistic regression model (Table 2) showed that having had unprotected sex with their last sexual partner (AOR=2.84; 95% CI=1.09–7.40) and meeting screening criteria (AUDIT score ≥8) for having an underlying AUD (AOR=2.14; 95% CI=1.01–4.54) were independently correlated with HIV seropositive MSM who were unaware of their status.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest biobehavioral HIV serosurveillance survey to be conducted among MSM in Peru, which includes extensive HIV risk behaviors, standardized testing for HIV and STIs like syphilis, and the inclusion of standardized measures of alcohol-related risk, thereby providing important HIV prevention and treatment data about MSM.

Most concerning about these results is the exceedingly high proportion of HIV-infected MSM who were unaware of their HIV status, despite nearly two thirds having been previously HIV tested at some point. This represents the only such study in Latin America, though the data from different international settings provide variable findings. For example, a recent modeling study in Switzerland showed that 81.8% of new infections were attributable to HIV-infected MSM who were unaware of their status (24), underscoring the public health consequences of ensuring that MSM are regularly screened and aware. Recent studies among MSM in Paris and Melbourne, similarly recruited using convenience sampling, showed that only 19.7% and 31.1%, respectively, of those who were HIV-infected were unaware of their status (25, 26), indicating a vast difference between these samples from high-income countries and ours in a middleincome setting. A study among MSM in South Africa (n=307) found that 20.6% of the sample tested HIV seropositive, but only 2.6% of the participants self-reported being HIV-infected (27). A study among MSM in China, however, showed a similar proportion (93%) as ours of being unaware of HIV seropositive status (28), but this study drew from a very small sample size (n=15), thereby making it challenging to draw conclusions, and the sample size was too small to examine correlates of being unaware of knowing their status. A recent study in Kenya also showed a high percentage of HIV seropositive participants who were unaware of their status (83.6%) (29), but did not disaggregate their data for MSM. While these international studies of MSM being unaware of their HIV status did not specifically examine the impact of AUDs on whether MSM were aware of their HIV status or not, the study by Lane et al (27) used similar criteria that we did (AUDIT≥9, while we used WHO criteria of AUDIT≥8), and did not find an association with AUDs and HIV infection itself. It is possible that AUDs may play a differing role in HIV risks than they do in being tested for HIV.

Identification of HIV infection is the first, and an essential component of the Seek, Test and Treat strategy (5) and in this sample, nearly 90% were unaware of being HIV-infected. Previous data from Peru suggest that MSM do not regularly test for HIV (30), despite guidelines recommending biannual testing for at-risk individuals, although there are currently no specific guidelines in Peru for HIV testing among MSM. In the U.S., by comparison, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) now recommend at least annual HIV testing for sexually active MSM (31) and even as frequently as every 3 to 6 months (32), leaving considerable room for guidance in identifying HIV among MSM. Although nearly two thirds of our sample of newly HIV-infected MSM had been previously tested, no data were collected on last test or frequency of testing. It is therefore crucial for HIV prevention efforts to focus on strategies that increase testing coverage and identify the majority of HIV-infected persons (4) in order to link them to and retain them in care so that they may access preventive and life-prolonging antiretroviral treatment and ultimately reduce HIV transmission to others.

Another concerning finding of this study is that those who were unaware of being HIV-infected were engaging in exceedingly high risk behaviors that could result in transmission to others. The association of unprotected sex with not knowing one’s HIV-positive status is not unexpected, given the mode of transmission of HIV, as well as reports that HIV-infected individuals tend to reduce their HIV risk behaviors after learning of their HIV diagnosis (33). Though not ascertainable from our sample, others have suggested that serosorting (34), a behavior that involves selecting sexual partners of the same presumed HIV seropositive status, may be a strategy used by some HIV-positive men to reduce transmission to other. Future examinations should incorporate if this strategy is used by Peruvian MSM, but the incredibly high proportion who did not know their HIV status argues against this strategy being deployed in this sample.

The high prevalence of underlying AUDs among these HIV-infected MSM is very worrisome, however, especially given that AUDs were independently correlated with being unaware of being HIV-infected. Though not measured in this study, the contribution of childhood sexual abuse has been associated with drug and alcohol risk as well as HIV infection in a recent systematic review (35). Additionally, among individuals with HIV in several studies outside of Latin America, AUDs have also been associated with a number of poor HIV treatment outcomes, including decreased linkage to and retention in care, access to ART, ART adherence and achieving viral suppression in a recent systematic review (13). Although this review found that alcohol use was imprecisely measured across studies and most did not use standardized measures of AUDs, some notable examples included decreased ART adherence after binge drinking, decreased ART adherence in drinkers (defined as any alcohol consumption) compared to non-drinkers, increased likelihood of ART discontinuation in hazardous drinkers, increased numbers of hospital visits for binge drinkers, increased mental health visits for people with AUDs, to name a few (13).

While recent guidance has been provided by the World Health Organization (WHO) addressing the prevention and treatment of HIV and other STIs among MSM (36), AUDs are absent from this dialogue. As part of its recommendations, the WHO recommends that MSM should minimally have access to brief, evidence-based psychosocial interventions involving assessment, specific feedback and advice. The content of the specific feedback and advice, however, are purposefully vague in order to allow implementation of culturally appropriate targeted messages. These recommendations, however, fall short of the best evidence for treating AUDs, where medication-assisted therapies (37), such as the use of oral and extended-release naltrexone (XR-NTX) are superior to counseling-based therapies alone, especially those with more serious AUDs (38). Though XR-NTX has been demonstrated to be safe in treating HIV-infected opioid dependent persons (39), it has yet to be studied either among MSM or those receiving ART, where hepatotoxicity or other adverse consequences may undermine treatment efforts.

HIV-infected MSM who are unaware of their status were not only more likely to have an AUD, but independent from this, were engaging in unprotected sex, raising important prevention and treatment issues, specifically for implementing combination prevention modalities. In this case where AUD prevalence was exceedingly high, it is again crucial to systematically screen for AUDs and treat them using behavioral and/or biomedical interventions, including XR-NTX to reduce alcohol consumption, both before becoming HIV-infected, but also after becoming HIV-infected since AUDs are in themselves associated with high risk sexual behavior. Alcohol consumption increases sexual risk behaviors via various mechanisms including drinking environments, expectancies about its enhancement of sex and its psychogenic effects on decision making (40). Importantly, excessive alcohol consumption contributes negatively to other HIV treatment factors, including linkage and retention in care and adherence to ART (13, 41). Though this study did not explore reasons for lack of previous HIV testing among MSM, some potential explanations include lack of perceived risk (though risk was undeniably high), stigma associated with seeking testing (i.e., homosexuality) or perhaps, lack of commitment to self-care secondary to alcohol use, similar to correlations between AUDs and linkage to HIV care once diagnosed, retention in HIV care and receipt of ART and ART adherence (13). Nonetheless, the etiology for not being aware of being HIV seropositive and AUDs merits further exploration.

Despite the important findings gleaned from this study, several important limitations remain. First, the cross-sectional nature of this study only allows for correlation without confirming causality. Nevertheless, the strong and significant association observed between those who were unaware of their HIV infection and AUDs, as well as the high prevalence of AUDs among the Peruvian MSM population overall, suggest that AUDs play an important role in sexual risk taking and potential for ongoing HIV transmission. Second, the convenience sampling recruitment methods minimizes the generalization of these findings, yet the incredibly large sample size may marginally reduce this concern due to likely sufficient enrollment of commonly under-represented or ‘hidden’ subpopulations when analyzing smaller sample sizes. Last, absent from this study is documentation of whether the majority of alcohol consumption and HIV risk-taking are concurrent. Establishing concurrency, or not, would help identify the most effective HIV risk reduction interventions necessary for this high-risk group of MSM (42). For example, if alcohol consumption precedes or is contemporaneous with high-risk sexual behaviors, then treating the underlying AUD would likely result in reduced HIV risk. Until such relationships are firmly established, a combination of treatment of AUDs and HIV itself, along with increased HIV testing and promotion of behavioral sexual risk reduction strategies are crucial for reducing overall HIV transmission.

Conclusions

This study, based on an extensive survey of more than five thousand participants, has highlighted that a very high percentage of HIV-infected MSM in Peru were unaware of their infection and had a high prevalence of underlying AUDs. A strong and significant association was identified between both newly diagnosed HIV infection and high-risk sex and having an underlying and treatable AUD among Peruvian MSM. The alarmingly high prevalence among HIV-infected MSM underscores the importance of screening and treating AUDs using evidence-based strategies. Together, these findings confirm the importance of screening for and addressing alcohol and sexual risk behaviors as part of ongoing HIV prevention efforts among MSM. The low proportion of HIV-infected MSM who had undergone recent HIV testing underscores the importance of expanding testing and treatment strategies in order to reduce the proportion of HIV-infected MSM who are unaware of their status, so that they can access and be linked to appropriate care.

Table 1.

Comparison of HIV-infected MSM who were Aware or Unaware of Being HIV-infected (N=420)

| Covariates | Total N=420 (%) |

HIV Status | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aware N=43 (10.2%) |

Unaware N=377 (89.8%) |

|||

| Never previously HIV tested | 142 (33.8) | NA | 142 (37.7) | - |

| Unprotected sex with last partner | 148 (35.2) | 7 (16.3) | 141 (37.9) | 0.005 |

| Unprotected sex with any of last 3 partners | 159 (37.9) | 12 (33.3) | 147 (47.1) | 0.116 |

| HIV+ sexual partner in previous 6 months | 37 (8.8) | 6 (14) | 31 (8.2) | 0.209 |

| Sex work in previous 6 months | 169 (40.2) | 17 (39.5) | 152 (40.8) | 0.878 |

| More than 5 partners in previous 6 months | 198 (47.1) | 20 (5.4) | 178 (51.3) | 0.750 |

| STI in previous 6 months | 97 (23.1) | 9 (20.9) | 88 (23.6) | 0.696 |

| Alcohol use disorder (AUDIT≥8) | 232 (55.2) | 20 (46.5) | 212 (57) | 0.190 |

| Syphilis infection | 80 (19.0) | 11 (26.8) | 69 (18.6) | 0.199 |

| Transgender | 104 (24.8) | 8 (18.6) | 96 (25.7) | 0.306 |

| Self-identified as gay | 397 (94.5) | 41 (95.3) | 356 (95.4) | 0.978 |

| Drug use in the previous 3 months | 56 (13.3) | 4 (9.3) | 52 (14.1) | 0.389 |

| Stable (male) partner (previous 3 partners) | 162 (38.6) | 20 (46.5%) | 142 (37.7%) | 0.259 |

| Location in Lima (vs. other) | 333 (79.3) | 34 (79.1%) | 299 (79.3%) | 0.971 |

| Mean number of sexual partners in the previous 3 months, (S.D.) | 11.4 (17.6) | 16.4 (38.7) | 0.411 | |

| Mean age, years (S.D.) | 33.4 (8.3) | 30.3 (8.2) | 0.017 | |

Legend: STI=sexually transmitted infection; S.D.=standard deviation

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the subjects who participated in this study; all the medical and research personnel at Impacta, Peru; Dr. Jeffrey Wickersham at the Yale AIDS Program and the Yale University StatLab for their help and advice with the statistical analyses; Enrico Ferro at Yale College; Paula Dellamura and Ruthanne Marcus at the Yale AIDS Program for their continued support of this project.

Funding: This research was funded by The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria grants PER-506-G03-H and PER-607-G05-H awarded to CARE PERU; unrestricted discretionary core funds from Asociacion Civil Impacta Educacion y Salud; and from the National Institute on Drug Abuse through research (R01 DA032106) and career development awards (K24 DA017072) to FLA. The funding sources played no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Since the original submission, this paper has been selected for presentation as an oral abstract at the International AIDS Society Conference in Kuala Lumpur, in June/July 2013.

References

- 1.Beyrer C, Baral SD, van Griensven F, Goodreau SM, Chariyalertsak S, Wirtz AL, et al. Global epidemiology of HIV infection in men who have sex with men. Lancet. 2012;380(9839):367–377. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60821-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587–2599. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charlebois ED, Das M, Porco TC, Havlir DV. The effect of expanded antiretroviral treatment strategies on the HIV epidemic among men who have sex with men in San Francisco. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(8):1046–1049. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Granich RM, Gilks CF, Dye C, De Cock KM, Williams BG. Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission: a mathematical model. Lancet. 2009;373(9657):48–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61697-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Griensven F, de Lind van Wijngaarden JW, Baral S, Grulich A. The global epidemic of HIV infection among men who have sex with men. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2009;4(4):300–307. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32832c3bb3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia PJ, Holmes KK, Carcamo CP, Garnett GP, Hughes JP, Campos PE, et al. Prevention of sexually transmitted infections in urban communities (Peru PREVEN): a multicomponent community-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379(22341824):1120–1128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61846-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanchez J, Lama JR, Kusunoki L, Manrique H, Goicochea P, Lucchetti A, et al. HIV-1, sexually transmitted infections, and sexual behavior trends among men who have sex with men in Lima, Peru. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44(17279049):578–585. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318033ff82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beyrer C, Wirtz AL, Walker D, Johns B, Sifakis F, Baral SD. The Global HIV Epidemics among Men Who Have Sex with Men. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lama JR, Lucchetti A, Suarez L, Laguna-Torres VA, Guanira JV, Pun M, et al. Association of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection and syphilis with human immunodeficiency virus infection among men who have sex with men in Peru. J Infect Dis. 2006;194(10):1459–1466. doi: 10.1086/508548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heath J, Lanoye A, Maisto SA. The role of alcohol and substance use in risky sexual behavior among older men who have sex with men: a review and critique of the current literature. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(3):578–589. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9921-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leigh BC, Stall R. Substance use and risky sexual behavior for exposure to HIV. Issues in methodology, interpretation, and prevention. American Psychologist. 1993;48(10):1035–1045. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.10.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azar MM, Springer SA, Meyer JP, Altice FL. A systematic review of the impact of alcohol use disorders on HIV treatment outcomes, adherence to antiretroviral therapy and health care utilization. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;112(3):178–193. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Samet JH, Mulvey KP, Zaremba N, Plough A. HIV testing in substance abusers. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1999;25(2):269–280. doi: 10.1081/ada-100101860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Kaufman M, Cain D, Jooste S. Alcohol use and sexual risks for HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review of empirical findings. Prev Sci. 2007;8(17265194):141–151. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stall R, Purcell DW. Intertwining Epidemics: A Review of Research on Substance Use Among Men Who Have Sex with Men and Its Connection to the AIDS Epidemic. AIDS and Behavior. 2000;4(2):181–192. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Babor TF, Delafuente JR, Saunders J. AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Health Care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ludford KT, Vagenas P, Lama JR, Peinado J, Gonzales P, Leiva R, et al. Screening for Alcohol Use Disorders and Drug Use and Their Associateion With High Risk Sexual Behaviors Among Men Who Have Sex with Men in Peru. Under Review. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodman LA. Snowball sampling. Ann Math Stat. 1961;32(1):148–170. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Workowski KA, Berman SM. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and mortality weekly report Recommendations and reports / Centers for Disease Control. 2006;55(RR-11):1–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reinert DF, Allen JP. The alcohol use disorders identification test: an update of research findings. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(2):185–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larsen SA, Steiner BM, Rudolph AH. Laboratory diagnosis and interpretation of tests for syphilis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8(1):1–21. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanchez J, Lama JR, Peinado J, Paredes A, Lucchetti A, Russell K, et al. High HIV and ulcerative sexually transmitted infection incidence estimates among men who have sex with men in Peru: awaiting for an effective preventive intervention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51(Suppl 1):47–51. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a2671d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Sighem A, Vidondo B, Glass TR, Bucher HC, Vernazza P, Gebhardt M, et al. Resurgence of HIV infection among men who have sex with men in Switzerland: mathematical modelling study. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e44819. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Velter A, Barin F, Bouyssou A, Guinard J, Leon L, Le Vu S, et al. HIV Prevalence and Sexual Risk Behaviors Associated with Awareness of HIV Status Among Men Who Have Sex with Men in Paris, France. AIDS Behav. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0303-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pedrana AE, Hellard ME, Wilson K, Guy R, Stoove M. High rates of undiagnosed HIV infections in a community sample of gay men in Melbourne, Australia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59(1):94–99. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182396869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lane T, Raymond HF, Dladla S, Rasethe J, Struthers H, McFarland W, et al. High HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men in Soweto, South Africa: results from the Soweto Men's Study. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(3):626–634. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9598-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi KH, Lui H, Guo Y, Han L, Mandel JS. Lack of HIV testing and awareness of HIV infection among men who have sex with men, Beijing, China. AIDS education and prevention : official publication of the International Society for AIDS Education. 2006;18(1):33–43. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cherutich P, Kaiser R, Galbraith J, Williamson J, Shiraishi RW, Ngare C, et al. Lack of knowledge of HIV status a major barrier to HIV prevention, care and treatment efforts in Kenya: results from a nationally representative study. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e36797. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blas MM, Alva IE, Cabello R, Carcamo C, Kurth AE. Risk behaviors and reasons for not getting tested for HIV among men who have sex with men: an online survey in Peru. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e27334. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, Janssen RS, Taylor AW, Lyss SB, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and mortality weekly reports Recommendations and reports / Centers for Disease Control. 2006;55(RR-14):1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.HIV testing among men who have sex with men--21 cities, United States, 2008. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011. Report No.: 1545-861X (Electronic) 0149-2195 (Linking) Contract No.: 21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Metsch LR, Pereyra M, Messinger S, Del Rio C, Strathdee SA, Anderson-Mahoney P, et al. HIV transmission risk behaviors among HIV-infected persons who are successfully linked to care. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(4):577–584. doi: 10.1086/590153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eaton LA, Kalichman SC, O'Connell DA, Karchner WD. A strategy for selecting sexual partners believed to pose little/no risks for HIV: serosorting and its implications for HIV transmission. AIDS Care. 2009;21(10):1279–1288. doi: 10.1080/09540120902803208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lloyd S, Operario D. HIV risk among men who have sex with men who have experienced childhood sexual abuse: systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS education and prevention : official publication of the International Society for AIDS Education. 2012;24(3):228–241. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2012.24.3.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Recommendations for a public health approach. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. Prevention and treatment of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men and transgender people. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Altice FL, Kamarulzaman A, Soriano VV, Schechter M, Friedland GH. Treatment of medical, psychiatric, and substance-use comorbidities in people infected with HIV who use drugs. Lancet. 2010;376(9738):59–79. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60829-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anton RF, O'Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, Cisler RA, Couper D, Donovan DM, et al. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295(17):2003–2017. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krupitsky E, Nunes EV, Ling W, Illeperuma A, Gastfriend DR, Silverman BL. Injectable extended-release naltrexone for opioid dependence: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9776):1506–1513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60358-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Kaufman M, Cain D, Jooste S. Alcohol use and sexual risks for HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review of empirical findings. Prev Sci. 2007;8(2):141–151. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Binford M, Kahana S, Altice FL. A Systematic Review of Antiretroviral Adherence Interventions for HIV-Infected People Who Use Drugs. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2012;9(4):287–312. doi: 10.1007/s11904-012-0134-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vosburgh HW, Mansergh G, Sullivan PS, Purcell DW. A review of the literature on event-level substance use and sexual risk behavior among men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(6):1394–1410. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0131-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]