Abstract

Phyllodes tumors (PTs) are classified as fibroepithelial tumors and their histologic grade is determined primarily by the features of the stromal component. In this study, we examined the expression profiles of autophagy-related proteins in the stromal component of PTs and analyzed their clinical implications. We selected 204 human PT samples which were excised and diagnosed at Severance Hospital from 2000 to 2008 and created tissue microarray (TMA) blocks. Immunohistochemical assays for autophagy-related proteins (beclin-1, LC3A, LC3B, and p62) were then performed on these samples. The surgical specimens from higher grade PTs less frequently displayed cytoplasmic expression of beclin-1, LC3A, LC3B, and p62 in the stromal component (p<0.001). In univariate analysis, the following profiles were associated with shorter disease-free survival and overall survival: nuclear beclin-1 positivity in the stromal component (p=0.013 and p=0.044, respectively), LC3A positivity in the stromal component (p<0.001 and p<0.001, respectively), and p62 positivity in the stromal component (p=0.012 and p=0.004, respectively). In conclusion, we determined that increased activity of autophagy-related proteins correlated with a higher histologic grade and poorer prognosis in PTs. These results lead us to conclude that the autophagy activity of the stromal cells plays a key role in the progression of PTs.

Keywords: Breast, phyllodes tumor, autophagy

Introduction

Phyllodes tumor (PT) is a relatively uncommon fibroepithelial tumor, comprising only 0.3-1.5% of all breast tumors [1]. However, it is hard to distinguish PT from other fibroepithelial tumors because of its heterogeneous histologic features [1,2]. Although PT contains both epithelial and stromal components which could be neoplastic, on histological grading, it is classified primarily by the features of the stromal components as follows: cytologic atypia of stromal cells, stromal hypercellularity and overgrowth, sarcomatous change, and mitotic activity [3,4]. Clinically, high-grade PTs can present with malignant behaviors such as local recurrence or distant metastasis. Therefore, it is necessary to discover reliable markers for the malignant features of the stromal component to accurately predict tumor progression.

Autophagy is defined as a catabolic pathway of lysosomal degradation of the cellular components. Among the three types of autophagy, macroautophagy particularly involves the stress-response pathway to maintain cellular homeostasis by removal of dysfunctional or damaged cellular components, as well as by recycling useful cellular components [5-9]. In this study, autophagy is referred to as macroautophagy to explain the cellular process within the cancer cells.

Cancer cells thrive in harsh environments, such as hypoxic or low nutrient states, surviving through angiogenesis and/or aerobic glycolysis. However, in the case of aggressive malignant tumors, it is hard for cancer cells to meet the high metabolic demand so that they cannot fully recover using the classical pathways. Autophagy as an alternative metabolic pathway conserves energy within the cancer cells by recycling cytoplasmic components [10,11]. In contrast, unrestrained autophagy could induce progressive consumption of cellular constituents and ultimately lead to cell death [12,13]. Interestingly, autophagy has a profound effect on both tumor suppression and tumor progression. However, not much was known about the expression profiles of autophagy-related proteins in PTs until recently.

In this study, we explored the relevance of autophagy-related protein expression patterns and histologic grade in human PTs. On the basis of this observation, we evaluated the ability of autophagy-related proteins to predict prognosis.

Methods and materials

Patient selection and clinicopathologic analysis

This retrospective study was approved by the institutional review board of Yonsei University Severance Hospital. Our inclusion criteria defined a study population of 204 patients who had been histologically diagnosed with PT after having tumors excised at Yonsei University Severance Hospital from 2000 to 2008. All tissues were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. All archival hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)–stained slides were reviewed by three pathologists and histologic grading was performed based on the criteria of the WHO Blue Book [1]. Histologic parameters such as stromal cellularity (mild, moderate, and severe), stromal atypia (mild, moderate, and severe), stromal mitosis (10 HPFs), stromal overgrowth, and tumor margin (expanding or infiltrative) were evaluated on H&E–stained slides. Included clinical parameters were patient age at initial diagnosis, sex, tumor recurrence, and tumor metastasis.

Tissue microarray

We selected formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor tissue samples after retrospective review of H&E–stained slides of human PTs. The most representative areas of each tumor sample were assembled in a 5x4 array after extraction of tumor cores as small as 5 mm in diameter. We attempted to include all of the epithelial and stromal components of PTs in the recipient blocks. Each PT sample had two tissue cores in TMA and each separate tissue core was assigned a unique tissue microarray location number that was linked to a database including other clinicopathologic data.

Immunohistochemistry

All immunostainings were performed using FFPE tissue sections. Five μm-thick sections were obtained with a microtome, transferred onto adhesive slides, and dried at 62°C for 30 minutes. After incubation with primary antibodies for beclin-1 (polyclonal, 1:100, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), LC3A (EP1528Y, 1:100, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), LC3B (polyclonal, 1:100, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), and p62 (SQSTM1, 1:100, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), immunodetection was performed with biotinylated anti-mouse immunoglobulin, followed by peroxidase-labeled streptavidin using a labeled streptavidin biotin kit with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine chromogen as substrate. Optimal primary antibody incubation time and concentration were determined via serial dilution for each immunohistochemical assay with an identically fixed and embedded tissue block. The primary antibody incubation step was omitted in the negative control. A positive control was included for each experiment; Beclin-1: normal breast tissue, LC3A and LC3B: brain tissue, and p62: spleen tissue. Slides were counterstained with Harris hematoxylin. The staining was interpreted by two pathologists on a multiview microscope.

For measurement of immunostaining intensity, we divided PTs in four groups as follows: 0 (negative), 1 (weakly positive), 2 (moderately positive), and 3 (strongly positive). For measurement of proportion of stained cells, we divided PTs in three groups as follows: 1 (negative), 2 (positive less than 30%), and 3 (positive more than 30%). Our indication standard for estimation of immunohistochemical results for beclin-1, LC3A, LC3B, and p62 was immunostaining intensity multiplied by the proportion of stained cells. The total score after multiplication was divided as follows: 0 to 1 as negative and 2 to 9 as positive [14].

Statistical analysis

Data were processed using SPSS for Windows, version 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Student’s t and Fisher’s exact tests were used to examine any difference in continuous and categorical variables, respectively. When analyzing data with multiple comparisons, a corrected p-value with application of Bonferroni multiple comparison procedure was used. Significance was assumed when P<0.05. Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log-rank statistics were employed to evaluate time to tumor metastasis and time to survival. Multivariate regression analysis was performed using the Cox proportional hazards model.

Results

Expression of autophagy-related proteins according to the histologic grade of PT

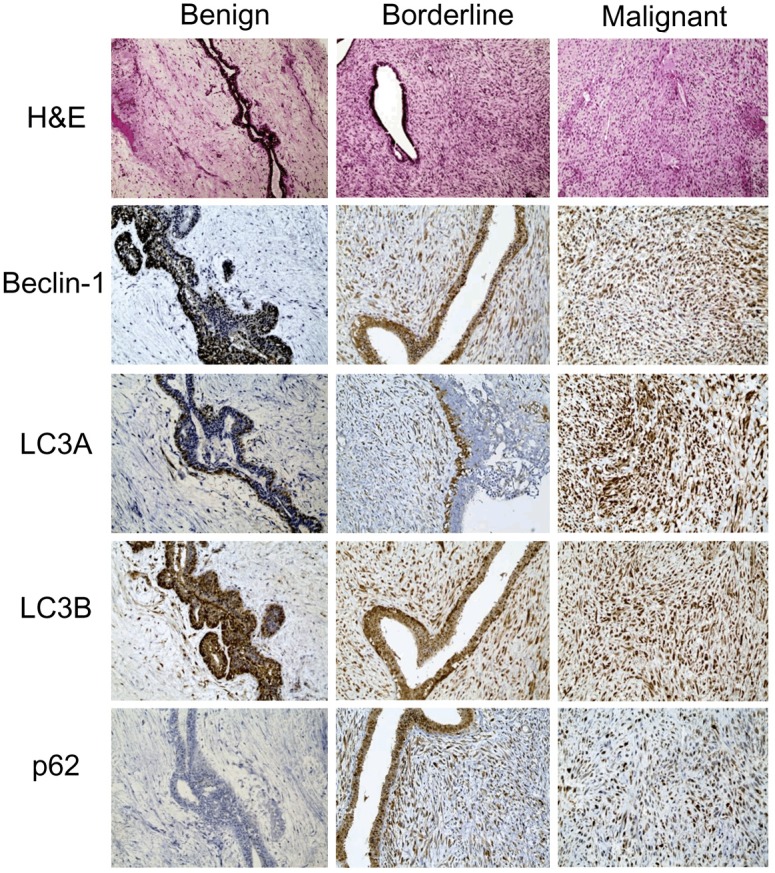

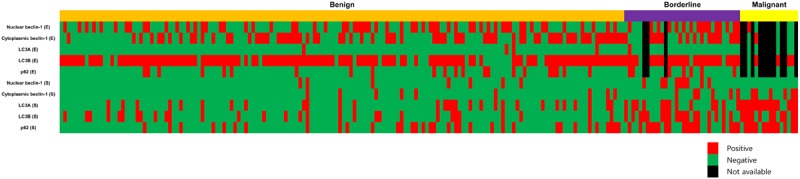

In Table 1, we compared the histologic grade of 204 PTs to the other parameters, and found that a higher histologic grade was associated with increased stromal cellularity, atypia, mitosis, overgrowth, infiltrative tumor margin, and frequent tumor recurrence and metastasis (p<0.001). To examine autophagy activity in the PTs, we performed immunohistochemistry of autophagy-related proteins (Figure 1). Proteins used to assess autophagy activities were as follows: beclin-1 as a participant in nucleation [15-18], LC3 as a participant in autophagosome formation [19-21], and p62 as a scaffold protein that conveys ubiquitinated proteins to the autophagosome [22,23]. Figure 2 is a representative heatmap of the expression of autophagy-related proteins according to the histologic grade of PTs. On immunohistochemical analysis, a higher histologic grade correlated with increased expression of autophagy-related proteins in the stromal component (p<0.001), although the epithelial component had nothing distinctive about it (Tables 2, 3 and 4). We assumed that the autophagy activity in the stromal component had a major impact on tumor progression in PTs.

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic characteristics of patients with phyllodes tumor

| Parameter | Number of Patients N=204 (%) | Phyllodes tumor (%) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Benign N=156 | Borderline N=32 | Malignant N=16 | |||

| Age (years, mean±SD) | 40.2±12.3 | 38.9±12.2 | 43.1±11.0 | 47.6±12.9 | 0.009 |

| Tumor size (Cm, mean±SD) | 4.0±2.6 | 3.6±2.1 | 4.2±2.5 | 6.7±4.6 | <0.001 |

| Stromal cellularity | <0.001 | ||||

| Mild | 123 (60.3) | 122 (78.2) | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Moderate | 68 (33.3) | 34 (21.8) | 27 (84.4) | 7 (43.8) | |

| Marked | 13 (6.4) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (12.5) | 9 (56.3) | |

| Stromal atypia | <0.001 | ||||

| Mild | 161 (78.9) | 154 (98.7) | 7 (21.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Moderate | 33 (16.2) | 2 (1.3) | 23 (71.9) | 8 (50.0) | |

| Marked | 10 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.3) | 8 (50.0) | |

| Stromal mitosis | <0.001 | ||||

| 0–4 / 10 HPFs | 159 (77.9) | 156 (100.0) | 3 (9.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 5–9 / 10 HPFs | 34 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) | 29 (90.6) | 5 (31.3) | |

| ≥10 / 10 HPFs | 11 (5.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (68.8) | |

| Stromal overgrowth | <0.001 | ||||

| Absent | 187 (91.7) | 156 (100.0) | 29 (90.6) | 2 (12.5) | |

| Present | 17 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (9.4) | 14 (87.5) | |

| Tumor margin | |||||

| Circumscribed | 183 (89.7) | 153 (98.1) | 24 (75.0) | 6 (37.5) | |

| Infiltrative | 21 (10.3) | 3 (1.9) | 8 (25.0) | 10 (62.5) | |

| Tumor local recurrence | 18 (8.8) | 5 (3.2) | 6 (18.8) | 7 (43.8) | <0.001 |

| Distance metastasis | 8 (3.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.1) | 7 (43.8) | <0.001 |

SD, standard deviation; HPFs, high-power fields.

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical stains of autophagy-related proteins in phyllodes tumors. Expression of cytoplasmic beclin-1, LC3A, LC3B, and p62 in the stromal component increases as the histologic grade of phyllodes tumor increases.

Figure 2.

A heatmap of the expression of autophagy-related proteins according to the histologic grade of phyllodes tumor.

Table 2.

Expression of autophagy-related proteins according to the histologic grade of phyllodes tumor

| Parameter | Number of Patients N=204 (%) | Phyllodes tumor (%) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Benign N=156 | Borderline N=32 | Malignant N=16 | |||

| Nuclear beclin-1 (E)* | 0.232 | ||||

| Negative | 111 (58.4) | 95 (60.9) | 13 (44.8) | 3 (60.0) | |

| Positive | 79 (41.6) | 61 (39.1) | 16 (55.2) | 2 (40.0) | |

| Cytoplasmic beclin-1 (E)* | 0.933 | ||||

| Negative | 101 (53.2) | 84 (53.8) | 13 (44.8) | 4 (80.0) | |

| Positive | 89 (46.8) | 72 (46.2) | 16 (55.2) | 1 (20.0) | |

| Nuclear beclin-1 (S) | 0.090 | ||||

| Negative | 188 (92.2) | 149 (95.5) | 23 (71.9) | 16 (100.0) | |

| Positive | 16 (7.8) | 7 (4.5) | 9 (28.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Cytoplasmic beclin-1 (S) | <0.001 | ||||

| Negative | 183 (89.7) | 147 (94.2) | 26 (81.3) | 10 (62.5) | |

| Positive | 21 (10.3) | 9 (5.8) | 6 (18.8) | 6 (37.5) | |

| LC3A (E)* | 0.980 | ||||

| Negative | 185 (97.4) | 152 (97.4) | 28 (96.6) | 5 (100.0) | |

| Positive | 5 (2.6) | 4 (2.6) | 1 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| LC3A (S) | <0.001 | ||||

| Negative | 148 (72.5) | 127 (81.4) | 19 (59.4) | 2 (12.5) | |

| Positive | 56 (27.5) | 29 (18.6) | 13 (40.6) | 14 (87.5) | |

| LC3B (E)* | 0.421 | ||||

| Negative | 34 (17.9) | 30 (19.2) | 3 (10.3) | 1 (20.0) | |

| Positive | 156 (82.1) | 126 (80.8) | 26 (89.7) | 4 (80.0) | |

| LC3B (S) | <0.001 | ||||

| Negative | 145 (71.1) | 126 (80.8) | 14 (43.8) | 5 (31.3) | |

| Positive | 59 (28.9) | 30 (19.2) | 18 (56.3) | 11 (68.8) | |

| p62 (E)* | 0.650 | ||||

| Negative | 161 (84.7) | 134 (85.9) | 22 (75.9) | 5 (100.0) | |

| Positive | 29 (15.3) | 22 (14.1) | 7 (24.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| p62 (S) | <0.001 | ||||

| Negative | 140 (68.6) | 122 (78.2) | 14 (43.8) | 4 (25.0) | |

| Positive | 64 (31.4) | 34 (21.8) | 18 (56.3) | 12 (75.0) | |

14 cases without an epithelial component were excluded.

E, epithelial component. S, stromal component.

Table 3.

Correlation between clinicopathologic factors with expression of autophagy-related proteins in epithelial component*

| Parameters | Nuclear beclin-1 | Cytoplasmic beclin-1 | LC3A | LC3B | P62 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||

| (-) n=111 (%) | (+) n=79 (%) | p-value | (-) n=101 (%) | (+) n=89 (%) | p-value | (-) n=185 (%) | (+) n=5 (%) | p-value | (-) n=34 (%) | (+) n=156 (%) | p-value | (-) n=161 (%) | (+) n=29 (%) | p-value | |

| Stromal cellularity | 1.065 | 4.155 | 1.865 | 2.385 | 1.470 | ||||||||||

| Mild | 78 (70.3) | 45 (57.0) | 66 (65.3) | 57 (64.0) | 121 (65.4) | 2 (40.0) | 25 (73.5) | 98 (62.8) | 107 (66.5) | 16 (55.2) | |||||

| Moderate | 28 (25.2) | 33 (41.8) | 32 (31.7) | 29 (32.6) | 58 (31.4) | 3 (60.0) | 7 (20.6) | 54 (34.8) | 49 (30.4) | 12 (41.4) | |||||

| Marked | 5 (4.5) | 1 (1.3) | 3 (3.0) | 3 (3.4) | 6 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (5.9) | 4 (2.6) | 5 (3.1) | 1 (3.4) | |||||

| Stromal atypia | 0.220 | 3.620 | 4.315 | 2.160 | 0.230 | ||||||||||

| Mild | 99 (89.2) | 62 (78.5) | 87 (86.1) | 74 (83.1) | 157 (84.9) | 4 (80.0) | 31 (91.2) | 130 (83.3) | 140 (87.0) | 21 (72.4) | |||||

| Moderate | 11 (9.9) | 15 (19.0) | 12 (11.9) | 14 (15.7) | 25 (13.5) | 1 (20.0) | 2 (5.9) | 24 (15.4) | 19 (11.8) | 7 (24.1) | |||||

| Marked | 1 (0.9) | 2 (2.5) | 2 (2.0) | 1 (1.1) | 3 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.9) | 2 (1.3) | 2 (1.2) | 1 (3.4) | |||||

| Stromal mitosis | 1.175 | 2.905 | 4.415 | 3.370 | 3.165 | ||||||||||

| 0–4 / 10 HPFs | 96 (86.5) | 63 (79.7) | 86 (85.1) | 73 (82.0) | 155 (83.8) | 4 (80.0) | 30 (88.2) | 129 (82.7) | 136 (84.5) | 23 (79.3) | |||||

| 5–9 / 10 HPFs | 14 (12.6) | 15 (19.0) | 14 (13.9) | 15 (16.9) | 28 (15.1) | 1 (20.0) | 3 (8.8) | 26 (16.7) | 23 (14.3) | 6 (20.7) | |||||

| ≥10 / 10 HPFs | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | |||||

| Stromal overgrowth | 2.855 | 5.000 | 5.000 | 2.240 | 5.000 | ||||||||||

| Absent | 110 (99.1) | 77 (97.5) | 99 (98.0) | 88 (98.9) | 182 (98.4) | 5 (100.0) | ; | 33 (97.1) | 154 (98.7) | 158 (98.1) | 29 (100.0) | ||||

| Present | 1 (0.9) | 2 (2.5) | 2 (2.0) | 1 (1.1) | 3 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.9) | 2 (1.3) | 3 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | |||||

| Tumor margin | 5.000 | 3.945 | 0.220 | 5.000 | 3.495 | ||||||||||

| Circumscribed | 103 (92.8) | 73 (92.4) | 93 (92.1) | 83 (93.3) | 173 (93.5) | 3 (60.0) | 32 (94.1) | 144 (92.3) | 148 (91.9) | 28 (96.6) | |||||

| Infiltrative | 8 (7.2) | 6 (7.6) | 8 (7.9) | 6 (6.7) | 12 (6.5) | 2 (40.0) | 2 (5.9) | 12 (7.7) | 13 (8.1) | 1 (3.4) | |||||

| Tumor recurrence | 9 (8.1) | 3 (3.8) | 1.825 | 5 (5.0) | 7 (7.9) | 2.765 | 12 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 5.000 | 3 (8.8) | 9 (5.8) | 2.265 | 12 (7.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1.095 |

| Distance metastasis | 2 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 2.560 | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.1) | 5.000 | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 5.000 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.3) | 5.000 | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 5.000 |

14 cases without an epithelial component were excluded.

Table 4.

Correlation between clinicopathologic factors with expression of autophagy-related proteins in stromal component

| Parameters | Nuclear beclin-1 | Cytoplasmic beclin-1 | LC3A | LC3B | P62 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||

| (-) n=188 (%) | (+) n=16 (%) | p-value* | (-) n=183 (%) | (+) n=21 (%) | p-value* | (-) n=148 (%) | (+) n=56 (%) | p-value* | (-) n=145 (%) | (+) n=59 (%) | p-value* | (-) n=140 (%) | (+) n=64 (%) | p-value* | |

| Stromal cellularity | 0.250 | 0.010 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| Mild | 118 (62.8) | 5 (31.3) | 116 (63.4) | 7 (33.3) | 107 (72.3) | 16 (28.6) | 103 (71.0) | 20 (33.9) | 100 (71.4) | 23 (35.9) | |||||

| Moderate | 58 (30.9) | 10 (62.5) | 58 (31.7) | 10 (47.6) | 37 (25.0) | 31 (55.4) | 40 (27.6) | 28 (47.5) | 34 (24.3) | 34 (53.1) | |||||

| Marked | 12 (6.4) | 1 (6.3) | 9 (4.9) | 4 (19.0) | 4 (2.7) | 9 (16.1) | 2 (1.4) | 11 (18.6) | 6 (4.3) | 7 (10.9) | |||||

| Stromal atypia | 0.850 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| Mild | 152 (80.9) | 9 (56.3) | 152 (83.1) | 9 (42.9) | 131 (88.5) | 30 (53.6) | 128 (88.3) | 33 (55.9) | 126 (90.0) | 35 (54.7) | |||||

| Moderate | 26 (13.8) | 7 (43.8) | 25 (13.7) | 8 (38.1) | 15 (10.1) | 18 (32.1) | 13 (9.0) | 20 (33.9) | 13 (9.3) | 20 (31.3) | |||||

| Marked | 10 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (3.3) | 4 (19.0) | 2 (1.4) | 8 (14.3) | 4 (2.8) | 6 (10.2) | 1 (0.7) | 9 (14.1) | |||||

| Stromal mitosis | 0.155 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| 0–4 / 10 HPFs | 152 (80.9) | 7 (43.8) | 150 (82.0) | 9 (42.9) | 130 (87.8) | 29 (51.8) | 129 (89.0) | 30 (50.8) | 124 (88.6) | 35 (54.7) | |||||

| 5–9 / 10 HPFs | 25 (13.3) | 9 (56.3) | 25 (13.7) | 9 (42.9) | 16 (10.8) | 18 (32.1) | 13 (9.0) | 21 (35.6) | 13 (9.3) | 21 (32.8) | |||||

| ≥10 / 10 HPFs | 11 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (4.4) | 3 (14.3) | 2 (1.4) | 9 (16.1) | 3 (2.1) | 8 (13.6) | 3 (2.1) | 8 (12.5) | |||||

| Stromal overgrowth | 3.145 | 0.015 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| Absent | 173 (92.0) | 14 (87.5) | 172 (94.0) | 15 (71.4) | 145 (98.0) | 42 (75.0) | 142 (97.9) | 45 (76.3) | 136 (97.1) | 51 (79.7) | |||||

| Present | 15 (8.0) | 2 (12.5) | 11 (6.0) | 6 (28.6) | 3 (2.0) | 14 (25.0) | 3 (2.1) | 14 (23.7) | 4 (2.9) | 13 (20.3) | |||||

| Tumor margin | 3.365 | 1.215 | <0.001 | 0.005 | 0.060 | ||||||||||

| Circumscribed | 169 (89.9) | 14 (87.5) | 166 (90.7) | 17 (81.0) | 141 (95.3) | 42 (75.0) | 137 (94.5) | 46 (78.0) | 131 (93.6) | 52 (81.3) | |||||

| Infiltrative | 19 (10.1) | 2 (12.5) | 17 (9.3) | 4 (19.0) | 7 (4.7) | 14 (25.0) | 8 (5.5) | 13 (22.0) | 9 (6.4) | 12 (18.8) | |||||

| Tumor recurrence | 14 (7.4) | 4 (25.0) | 0.200 | 16 (8.7) | 2 (9.5) | 5.000 | 7 (4.7) | 11 (19.6) | 0.010 | 10 (6.9) | 8 (13.6) | 0.855 | 8 (5.7) | 10 (15.6) | 0.155 |

| Distance metastasis | 7 (3.7) | 1 (6.3) | 2.440 | 6 (3.3) | 2 (9.5) | 0.970 | 0 (0.0) | 8 (14.3) | <0.001 | 4 (2.8) | 4 (6.8) | 1.160 | 2 (1.4) | 6 (9.4) | 0.065 |

p-values are corrected for multiple testing using the Bonferroni correction.

When looking at the effect of autophagy activity on the progression of PT, we examined the correlation between expressions of autophagy-related proteins with clinicopathologic parameters (Tables 2, 3 and 4). As a result, expression of beclin-1, LC3A, LC3B, and p62 in the stromal cells, but not in the epithelial cells, was associated with increased stromal cellularity, increased stromal atypia, increased stromal mitosis, and stromal overgrowth (p<0.05). Particularly, LC3A expression of the stromal component was significantly associated with tumor recurrence and distant metastasis (p=0.010, and <0.001, respectively).

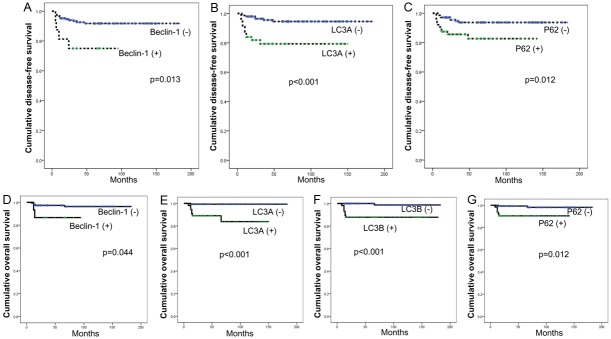

Impact of autophagy-related proteins on patient prognosis

Based on the above observation, we investigated the effect of each autophagy-related protein on the prognosis of the PT patients (Figure 3). We performed univariate analysis (Table 5) and found that factors associated with shorter disease-free survival and shorter overall survival were nuclear beclin-1 positivity in the stromal component (p=0.013, and p=0.044, respectively), LC3A positivity in the stromal component (p<0.001, and p<0.001, respectively), and p62 positivity in the stromal component (p=0.012, and p=0.004, respectively). Next, we performed Cox multivariate analysis (parameters included were stromal cellularity, stromal atypia, stromal mitosis, stromal overgrowth, tumor margin, nuclear beclin-1 in the stromal component, LC3A in the stromal component, and p62 in the stromal component); the results are shown in Table 6. Stromal overgrowth (hazard ratio: 12.381, 95% CI: 1.991-76.978, P=0.007), and nuclear beclin-1 positivity in the stromal component (hazard ratio: 3.358, 95% CI: 1.023-12.371, P=0.046) were correlated with shorter disease-free survival and stromal overgrowth (hazard ratio: 111.262, 95% CI: 6.175-2004.642, P=0.007) was associated with shorter overall survival.

Figure 3.

Disease-free survival and overall survival curves according to the status of autophagy-related proteins.

Table 5.

Univariate analysis of the impact of expression of autophagy-related proteins on prognosis by the log-rank test

| Parameter | Disease-free survival | Overall survival | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Median survival (95% CI) months | P-value | Median survival (95% CI) months | P-value | |

| Nuclear beclin-1 (E)* | 0.247 | 0.750 | ||

| Negative | 168 (159-177) | 181 (177-184) | ||

| Positive | 171 (164-179) | 176 (172-181) | ||

| Cytoplasmic beclin-1 (E)* | 0.319 | n/a | ||

| Negative | 174 (167-181) | n/a | ||

| Positive | 161 (150-172) | n/a | ||

| Nuclear beclin-1 (S) | 0.013 | 0.044 | ||

| Negative | 169 (162-176) | 177 (172-181) | ||

| Positive | 74 (56-91) | 84 (69-98) | ||

| Cytoplasmic beclin-1 (S) | 0.748 | 0.107 | ||

| Negative | 167 (160-174) | 177 (172-181) | ||

| Positive | 86 (75-97) | 86 (76-97) | ||

| LC3A (E)* | n/a | n/a | ||

| Negative | n/a | n/a | ||

| Positive | n/a | n/a | ||

| LC3A (S) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Negative | 174 (168-180) | 181 (179-184) | ||

| Positive | 121 (106-136) | 130 (116-144) | ||

| LC3B (E)* | 0.515 | 0.173 | ||

| Negative | 146 (132-160) | 154 (146-163) | ||

| Positive | 172 (165-179) | 181 (179-184) | ||

| LC3B (S) | 0.119 | <0.001 | ||

| Negative | 170 (162-177) | 181 (178-184) | ||

| Positive | 155 (140-170) | 158 (144-172) | ||

| p62 (E)* | n/a | n/a | ||

| Negative | n/a | n/a | ||

| Positive | n/a | n/a | ||

| p62 (S) | 0.012 | 0.004 | ||

| Negative | 172 (165-179) | 180 (176-183) | ||

| Positive | 120 (107-132) | 129 (120-139) | ||

14 cases without an epithelial component were excluded.

E, epithelial component. S, stromal component.

Table 6.

Independent prognostic factors for disease-free survival and overall survival by multivariate analysis

| Parameter | Disease-free survival | Overall survival | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P-value | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Stromal cellularity | 0.922 | 0.208 | ||||

| Mild vs. moderate/marked | 0.905 | 0.123-6.659 | 10.054 | 0.278-364.219 | ||

| Stromal atypia | 0.951 | 0.614 | ||||

| Mild vs. moderate/marked | 0.935 | 0.107-8.163 | 0.519 | 0.041-6.631 | ||

| Stromal mitosis | 0.972 | 0.447 | ||||

| 0-4 / 10 HPFs vs. ≥5 / 10 HPFs | 1.057 | 0.046-24.176 | 0.172 | 0.002-16.017 | ||

| Stromal overgrowth | 0.007 | 0.001 | ||||

| Absent vs. present | 12.381 | 1.991-76.978 | 111.262 | 6.175-2004.642 | ||

| Tumor margin | 0.693 | 0.514 | ||||

| Circumscribed vs. Infiltrative | 0.752 | 0.183-3.091 | 0.575 | 0.109-3.038 | ||

| Nuclear beclin-1 (S) | 0.046 | 0.321 | ||||

| Negative vs. Positive | 3.558 | 1.023-12.371 | 3.380 | 0.305-37.446 | ||

| LC3A (S) | 0.263 | 0.296 | ||||

| Negative vs. Positive | 1.905 | 0.616-5.890 | 3.776 | 0.312-45.721 | ||

| p62 (S) | 0.457 | 0.249 | ||||

| Negative vs. Positive | 1.500 | 0.516-4.364 | 3.056 | 0.458-20.406 | ||

S, stromal component.

Finally, we found that the expression of autophagy-related proteins adversely affected the disease-free survival and the overall survival of patients with PTs.

Discussion

It is known that autophagy is involved in both tumor suppression and tumor progression [10-13]. In this study, we investigated the expression profiles of autophagy-related proteins, beclin-1, LC3A, LC3B, and p62, in human PTs. We found that a higher histologic grade of PT was correlated with greater expression of beclin-1, LC3A, LC3B, and p62 proteins in the stromal component (p<0.001). These results support those of previous studies which have been performed in tumors from several other organs [15,18,20,24-31]. In terms of breast tumors, it is also known that expression of autophagy-related markers are associated with the histologic grade and the molecular subtype of breast cancer, although there is still no valid research evaluating the autophagy status in PTs [25].

Autophagy induction in cancer cells can occur due to hypoxia [10], and it has been previously demonstrated that expression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha (HIF-1α) and its downstream targets are associated with a higher histologic grade in fibroepithelial tumors of the breast [32]. Higher-grade PTs have been found to have relatively more stromal overgrowth than the lower-grade PTs, which is attributed to the fact that they frequently experience more hypoxia in the tumor microenvironment. It is thought that autophagy provides the nutrients needed for cancer survival and expression of HIF-1α allows higher-grade PTs to adapt to hypoxia. Furthermore, the metabolic demand has been shown to be elevated in higher-grade PTs based on the report that the expression of glycolysis-related proteins is associated with the histologic grade of PTs [33]. Therefore, we suggested that autophagy activity could compensate for the metabolic demand required for tumor survival up to a point. However, the activation of autophagy has a flip-side: tumor suppression may occur in the form of cell death induced by excessive consumption of the cellular components [12,13].

In terms of our results, the expression of nuclear beclin-1, LC3B, and p62 in the stromal component was related to poor prognosis in PT patients. Particularly, nuclear expression of beclin-1 in the stromal component was associated with shorter disease-free survival in multivariate analysis. We ascertained that beclin-1 could be expressed both in the nucleus and the cytoplasm as seen in the results of preceding studies [25,34]. In a study on brain tumors, beclin-1 protein shuttled between the nucleus and the cytoplasm and this expression shift was explained by loss of beclin-1 gene function [34]. In addition, there is a report that mutant beclin-1 is located in the nucleus [35]. Therefore, we suspect that the nuclear expression of beclin-1 is not related to autophagy regulation. Previous investigators have studied the correlation between beclin-1 expression and prognosis; some tumors with beclin-1 expression were associated with poor prognosis, while others showed a favorable prognosis [18,27,31,36]. Meanwhile, both loss of and overexpression of beclin-1 has been associated with poor prognosis in colon cancer patients [37]. Thus, we cannot determine whether the expression of beclin-1 is associated with prognosis in cancer patients unless further study on the correlation of the expression and the localization of beclin-1 and prognosis of tumors is performed. Otherwise, the expression of LC3B and p62 is known to be associated with poor prognosis in tumors of other organs, consistent with our results [38,39].

We performed immunohistochemical analysis, a static method, for evaluation of autophagy activity. However, autophagy is a multi-step dynamic process and thus, autophagy flux should be measured to evaluate the variations of autophagy activity over time [23]. Accordingly, our study is limited in that we used paraffin blocks of tumors and therefore could not verify that the changes resulted from autophagy activity.

We confirmed that the cytoplasmic beclin-1, LC3A, LC3B, and p62 expression in the stromal component increases as the histologic grade of PTs increases. Therefore, autophagy inhibitors might be candidates for anti-tumor agents for PTs and they have been reported to suppress tumor growth in other organs [40-43].

In conclusion, we demonstrated that the expression of cytoplasmic beclin-1, LC3A, LC3B, and p62 in the stromal component is associated with a higher histologic grade and poorer prognosis in PTs, and these results suggest the correlation of increased autophagy activity and tumor progression.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2012R1A1A1002886).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Tavassoli FA, Devilee P, editors. World Heath Organization Classification of Tumors. Lyon: IARC Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson B, Lawton T, Lehman C, Moe R. Phyllodes tumor. In: Morrow M, Osborne C, editors. Disease of the Breast. Philadelphia: Lippincott & Wilkins; 2004. pp. 991–1006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tan PH, Jayabaskar T, Chuah KL, Lee HY, Tan Y, Hilmy M, Hung H, Selvarajan S, Bay BH. Phyllodes tumors of the breast: the role of pathologic parameters. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005;123:529–540. doi: 10.1309/U6DV-BFM8-1MLJ-C1FN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sawyer EJ, Hanby AM, Ellis P, Lakhani SR, Ellis IO, Boyle S, Tomlinson IP. Molecular analysis of phyllodes tumors reveals distinct changes in the epithelial and stromal components. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1093–1098. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64977-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levine B, Klionsky DJ. Development by self-digestion: molecular mechanisms and biological functions of autophagy. Dev Cell. 2004;6:463–477. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mizushima N. Autophagy: process and function. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2861–2873. doi: 10.1101/gad.1599207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature. 2008;451:1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature06639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang Z, Klionsky DJ. Eaten alive: a history of macroautophagy. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:814–822. doi: 10.1038/ncb0910-814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murrow L, Debnath J. Autophagy as a stress-response and quality-control mechanism: implications for cell injury and human disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2013;8:105–137. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-020712-163918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Degenhardt K, Mathew R, Beaudoin B, Bray K, Anderson D, Chen G, Mukherjee C, Shi Y, Gelinas C, Fan Y, Nelson DA, Jin S, White E. Autophagy promotes tumor cell survival and restricts necrosis, inflammation, and tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roy S, Debnath J. Autophagy and tumorigenesis. Semin Immunopathol. 2010;32:383–396. doi: 10.1007/s00281-010-0213-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baehrecke EH. Autophagy: dual roles in life and death? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:505–510. doi: 10.1038/nrm1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Debnath J, Baehrecke EH, Kroemer G. Does autophagy contribute to cell death? Autophagy. 2005;1:66–74. doi: 10.4161/auto.1.2.1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Won KY, Kim GY, Kim YW, Song JY, Lim SJ. Clinicopathologic correlation of beclin-1 and bcl-2 expression in human breast cancer. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Y, Lu Y, Lu C, Zhang L. Beclin-1 expression is a predictor of clinical outcome in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and correlated to hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1alpha expression. Pathol Oncol Res. 2009;15:487–493. doi: 10.1007/s12253-008-9143-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li BX, Li CY, Peng RQ, Wu XJ, Wang HY, Wan DS, Zhu XF, Zhang XS. The expression of beclin 1 is associated with favorable prognosis in stage IIIB colon cancers. Autophagy. 2009;5:303–306. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.3.7491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pirtoli L, Cevenini G, Tini P, Vannini M, Oliveri G, Marsili S, Mourmouras V, Rubino G, Miracco C. The prognostic role of Beclin 1 protein expression in high-grade gliomas. Autophagy. 2009;5:930–936. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.7.9227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wan XB, Fan XJ, Chen MY, Xiang J, Huang PY, Guo L, Wu XY, Xu J, Long ZJ, Zhao Y, Zhou WH, Mai HQ, Liu Q, Hong MH. Elevated Beclin 1 expression is correlated with HIF-1alpha in predicting poor prognosis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Autophagy. 2010;6:395–404. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.3.11303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Ueno T, Yamamoto A, Kirisako T, Noda T, Kominami E, Ohsumi Y, Yoshimori T. LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. EMBO J. 2000;19:5720–5728. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.21.5720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sivridis E, Koukourakis MI, Zois CE, Ledaki I, Ferguson DJ, Harris AL, Gatter KC, Giatromanolaki A. LC3A-positive light microscopy detected patterns of autophagy and prognosis in operable breast carcinomas. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:2477–2489. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoshioka A, Miyata H, Doki Y, Yamasaki M, Sohma I, Gotoh K, Takiguchi S, Fujiwara Y, Uchiyama Y, Monden M. LC3, an autophagosome marker, is highly expressed in gastrointestinal cancers. Int J Oncol. 2008;33:461–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Komatsu M, Waguri S, Koike M, Sou YS, Ueno T, Hara T, Mizushima N, Iwata J, Ezaki J, Murata S, Hamazaki J, Nishito Y, Iemura S, Natsume T, Yanagawa T, Uwayama J, Warabi E, Yoshida H, Ishii T, Kobayashi A, Yamamoto M, Yue Z, Uchiyama Y, Kominami E, Tanaka K. Homeostatic levels of p62 control cytoplasmic inclusion body formation in autophagy-deficient mice. Cell. 2007;131:1149–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Levine B. Methods in mammalian autophagy research. Cell. 2010;140:313–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahn CH, Jeong EG, Lee JW, Kim MS, Kim SH, Kim SS, Yoo NJ, Lee SH. Expression of beclin-1, an autophagy-related protein, in gastric and colorectal cancers. APMIS. 2007;115:1344–1349. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2007.00858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi J, Jung W, Koo JS. Expression of autophagy-related markers beclin-1, light chain 3A, light chain 3B and p62 according to the molecular subtype of breast cancer. Histopathology. 2013;62:275–286. doi: 10.1111/his.12002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giatromanolaki A, Koukourakis MI, Harris AL, Polychronidis A, Gatter KC, Sivridis E. Prognostic relevance of light chain 3 (LC3A) autophagy patterns in colorectal adenocarcinomas. J Clin Pathol. 2010;63:867–872. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2010.079525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giatromanolaki A, Koukourakis MI, Koutsopoulos A, Chloropoulou P, Liberis V, Sivridis E. High Beclin 1 expression defines a poor prognosis in endometrial adenocarcinomas. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;123:147–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giatromanolaki AN, Charitoudis GS, Bechrakis NE, Kozobolis VP, Koukourakis MI, Foerster MH, Sivridis EL. Autophagy patterns and prognosis in uveal melanomas. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:1036–1045. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sivridis E, Koukourakis MI, Mendrinos SE, Karpouzis A, Fiska A, Kouskoukis C, Giatromanolaki A. Beclin-1 and LC3A expression in cutaneous malignant melanomas: a biphasic survival pattern for beclin-1. Melanoma Res. 2011;21:188–195. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e328346612c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thompson HG, Harris JW, Wold BJ, Lin F, Brody JP. p62 overexpression in breast tumors and regulation by prostate-derived Ets factor in breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2003;22:2322–2333. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu M, Gou WF, Zhao S, Xiao LJ, Mao XY, Xing YN, Takahashi H, Takano Y, Zheng HC. Beclin 1 expression is an independent prognostic factor for gastric carcinomas. Tumour Biol. 2013;34:1071–83. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0648-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuijper A, van der Groep P, van der Wall E, van Diest PJ. Expression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha and its downstream targets in fibroepithelial tumors of the breast. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7:R808–818. doi: 10.1186/bcr1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kwon JE, Jung WH, Koo JS. The expression of metabolism-related proteins in phyllodes tumors. Tumour Biol. 2013;34:115–124. doi: 10.1007/s13277-012-0518-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miracco C, Cosci E, Oliveri G, Luzi P, Pacenti L, Monciatti I, Mannucci S, De Nisi MC, Toscano M, Malagnino V, Falzarano SM, Pirtoli L, Tosi P. Protein and mRNA expression of autophagy gene Beclin 1 in human brain tumours. Int J Oncol. 2007;30:429–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Negri T, Tarantino E, Orsenigo M, Reid JF, Gariboldi M, Zambetti M, Pierotti MA, Pilotti S. Chromosome band 17q21 in breast cancer: significant association between beclin 1 loss and HER2/NEU amplification. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2010;49:901–909. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang JJ, Zhu YJ, Lin TY, Jiang WQ, Huang HQ, Li ZM. Beclin 1 expression predicts favorable clinical outcome in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP. Hum Pathol. 2011;42:1459–1466. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koukourakis MI, Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, Pitiakoudis M, Gatter KC, Harris AL. Beclin 1 over- and underexpression in colorectal cancer: distinct patterns relate to prognosis and tumour hypoxia. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:1209–1214. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rolland P, Madjd Z, Durrant L, Ellis IO, Layfield R, Spendlove I. The ubiquitin-binding protein p62 is expressed in breast cancers showing features of aggressive disease. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2007;14:73–80. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao H, Yang M, Zhao J, Wang J, Zhang Y, Zhang Q. High expression of LC3B is associated with progression and poor outcome in triple-negative breast cancer. Med Oncol. 2013;30:475. doi: 10.1007/s12032-013-0475-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amaravadi RK, Yu D, Lum JJ, Bui T, Christophorou MA, Evan GI, Thomas-Tikhonenko A, Thompson CB. Autophagy inhibition enhances therapy-induced apoptosis in a Myc-induced model of lymphoma. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:326–336. doi: 10.1172/JCI28833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carew JS, Medina EC, Esquivel JA 2nd, Mahalingam D, Swords R, Kelly K, Zhang H, Huang P, Mita AC, Mita MM, Giles FJ, Nawrocki ST. Autophagy inhibition enhances vorinostat-induced apoptosis via ubiquitinated protein accumulation. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:2448–2459. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00832.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carew JS, Nawrocki ST, Kahue CN, Zhang H, Yang C, Chung L, Houghton JA, Huang P, Giles FJ, Cleveland JL. Targeting autophagy augments the anticancer activity of the histone deacetylase inhibitor SAHA to overcome Bcr-Abl-mediated drug resistance. Blood. 2007;110:313–322. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-050260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gupta A, Roy S, Lazar AJ, Wang WL, McAuliffe JC, Reynoso D, McMahon J, Taguchi T, Floris G, Debiec-Rychter M, Schoffski P, Trent JA, Debnath J, Rubin BP. Autophagy inhibition and antimalarials promote cell death in gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14333–14338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000248107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]