Abstract

Plant roots consist of a meristematic zone of mitotic cells and an elongation zone of rapidly expanding cells, in which DNA replication often occurs without cell division, a process known as endoreduplication. The duration of the cell cycle and DNA replication, as measured by 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxy-uridine (EdU) incorporation, differed between the two regions (17 h in the meristematic zone, 30 h in the elongation zone). Two distinct subnuclear patterns of EdU signals, whole and speckled, marked nuclei undergoing DNA replication at early and late S phase, respectively. The boundary region between the meristematic and elongation zones was analysed by a combination of DNA replication imaging and optical estimation of the amount of DNA in each nucleus (C-value). We found a boundary cell with 4C nuclei exhibiting the whole pattern of EdU signals. Analyses of cells in the boundary region revealed that endoreduplication precedes rapid cell elongation in roots.

Size compensation is a universal phenomenon in which tissue size is adjusted by enlarging the cell volume accompanied by a low rate of cell division1,2,3,4,5. Cell expansion coupled with repeated rounds of DNA replication without cell division, known as endoreduplication (also referred to as endoreplication), has been observed in groups as diverse as bacteria6, insects7 humans8, and plants9,10. In multicellular organisms, coordination between cell expansion and endoreduplication is often essential for tissue growth and morphogenesis. Cell expansion accompanied by endoreduplication results in increased copy numbers of genes in the cell, which can increase the rates of biosynthetic production; this occurs in cells in the Drosophila salivary gland7. In many plants, including the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana, cell expansion accompanied by endoreduplication is closely related to the development of the root, hypocotyl, and endosperm tissues, the giant cells of the sepal, and the trichome and pavement cells in the leaf9,10. Light11, DNA damage12, pathogen attack13, phytohormones14, and cell cycle regulators9,15,16 affect this relationship. The root of A. thaliana is one of the most well characterized organs. It comprises the meristematic zone, in which random cell division occurs, and the elongation zone, in which endoreduplication occurs17. The size of cells gradually increases from the basal half of the meristem, and rapidly increases from start of the cell elongation zone18. However, the question of which comes first, endoreduplication or rapid cell expansion, has long been an important issue in plant development19,20. In this study, we studied the differences between mitotic and endoreduplication cell cycles using 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxy-uridine (EdU) to monitor DNA replication in the root meristem and elongation zones. The EdU method has several advantages over the classical method using 5-bromo-2′-deoxy-uridine (BrdU); unlike BrdU, EdU can be detected by a small molecule that can pass through cell walls, allowing analyses of intact plant tissues21,22,23. Using this method, we were able to define the boundary region between meristematic and elongation zones based on S phase-specific EdU signal patterns and C values (which reflect the amount of DNA) estimated by SYBR Green staining in each cell nucleus. Our analyses showed that DNA replication precedes rapid cell expansion in the boundary region.

Results

Determination of cell cycle duration and analysis of synchronization of DNA replication

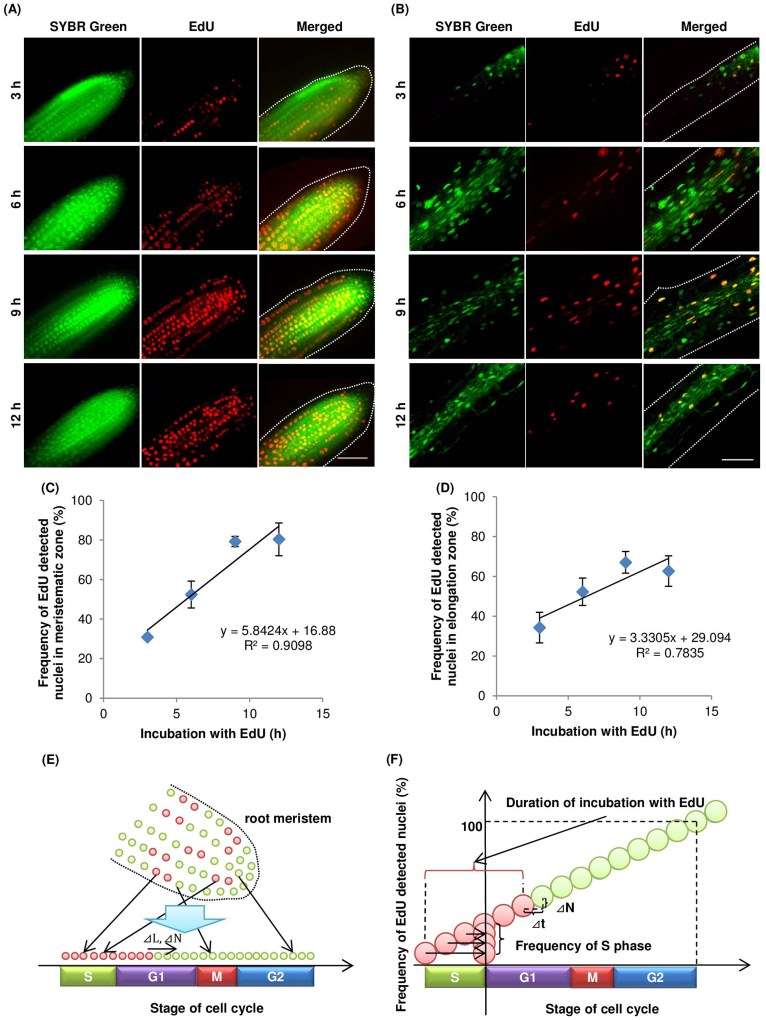

When roots of A. thaliana were incubated in liquid medium containing EdU for various periods, EdU-incorporated cells were detected in all cell layers (Figure 1A, B). The frequency of EdU-incorporated nuclei in the meristematic and elongation zones of the root increased proportionally with the incubation period (Figure 1C, D). The durations of the cell cycle and S phase were estimated by the linear function of the frequency of EdU-incorporated nuclei vs. the incubation period in EdU solution (Figure 1E, F). For cells in the meristematic and elongation zones, the cell-cycle durations were 17.1 h and 30.0 h, respectively, and the duration of the S-phase was 2.9 h and 8.7 h, respectively. In our analyses of the EdU method, the relationship between the frequency of EdU-positive cells and EdU incubation time was less proportional for cells in the elongation zone than for cells in the meristematic zone. This decreased proportionality was a result of endoreduplication, which caused variations in the DNA content in the nuclei of cells in the elongation zone of the A. thaliana root.

Figure 1. Visualization and frequency of nuclei undergoing DNA replication in A. thaliana roots.

A. thaliana seedlings were incubated in MS medium containing 10 μM EdU for indicated periods, fixed, and processed to detect EdU (red) and DNA staining with SYBR Green (green), as described in the Methods. Meristematic (A and C) and elongation (B and D) zones were analysed by confocal microscopy. (A and B) Representative images for each incubation time point. Scale bar = 50 μm. (C and D) Lines were drawn by least squares (n = 4). (E) Schematic figure of root meristem after EdU incorporation. Green and red circles indicate EdU-negative and positive nuclei, respectively. Cell-cycle stages of nuclei in the meristematic zone are random but can be placed in sequence if nuclei are abundant. L, stage of cell cycle; N, number of the EdU-positive nuclei. (F) Idealized graph of relationship between EdU incubation time and frequency of EdU-positive nuclei. Speed of cell cycle progression is related to increased frequency of EdU-positive nuclei (see equation 3 in Methods). The increase in the frequency of EdU-positive nuclei was calculated from the linear approximation obtained by plotting EdU incubation time (t) against frequency of EdU-positive nuclei (N).

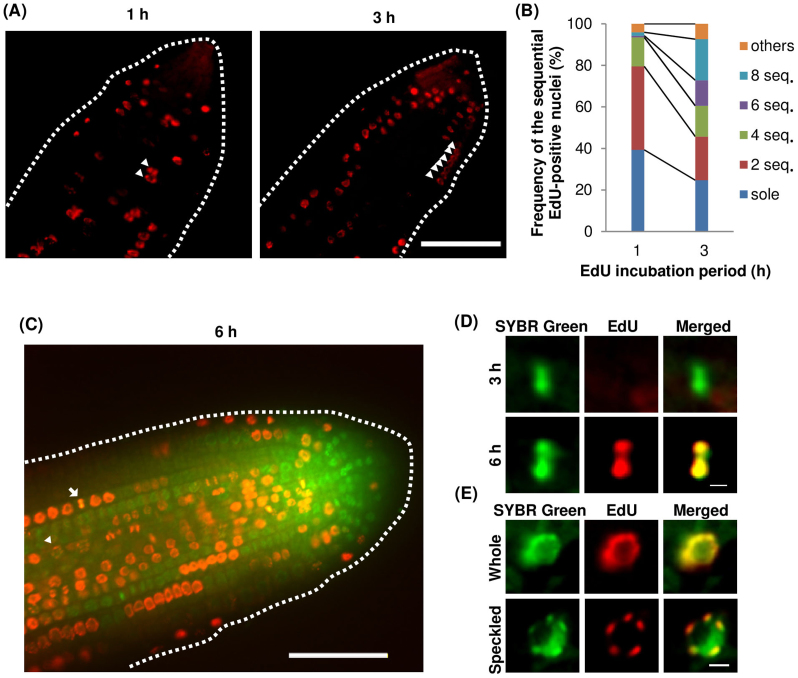

Interestingly, two to several adjacent EdU-positive nuclei were observed in A. thaliana roots even after a short exposure to EdU (Figure 2A). When the frequencies of adjacent EdU-positive nuclei in the meristematic zone of A. thaliana roots were compared between 1 h and 3 h EdU-incubation periods, the frequencies of six and eight adjacent EdU-positive nuclei were higher after 3 h incubation (Figure 2B). These results suggested that the cell cycle, or at least the S-phase of the cycle, tends to be synchronized in adjacent cells in the meristematic region, even though cell division occurs randomly in this region. Next, we analysed roots incubated with EdU for 3 h and 6 h. EdU-positive aligned chromosomes were detected in roots incubated with EdU for 6 h (Figure 2C, D), but not 3 h. In the cells that had incorporated EdU at the start of the incubation, the cell cycle had advanced to the G2 phase by 3 h and to metaphase by 6 h. This implied that the nuclei that had been in late S phase at the start of the incubation could not enter M phase within 3 h. Thus, the length of the G2 phase in cells in the meristematic zone was predicted to be between 3 h and 6 h.

Figure 2. Cell division patterns in the meristematic zone of A. thaliana roots.

(A) EdU-positive cells in the meristematic zone after 1 h and 3 h of EdU incorporation (performed as described in Figure 1). Arrowheads indicate EdU-incorporated nuclei in adjacent cells. Bar = 50 μm. (B) Frequency of 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 EdU-positive adjacent nuclei. (C) EdU-incorporated nuclei in the meristematic region after 6 h EdU incorporation. An arrowhead and an arrow indicate a speckled patterned nuclear and metaphase chromosomes, respectively. Scale bar = 50 μm. (D) Magnification of a metaphase cell after 3 h EdU incorporation (top) and 6 h EdU incorporation (bottom). (E) Magnifications of whole and speckled patterns of EdU signals. Bar = 3 μm.

EdU signal patterns can be used to classify DNA replication into early and late phases

Careful observations of EdU-positive nuclei revealed two types of EdU signal distributions; whole and speckled patterns (Figure 2E). The whole pattern was characterized by an even distribution of the EdU signal throughout the nucleoplasm (but not in the nucleolus). The speckled pattern was characterized by patches of EdU signals throughout the nucleoplasm. These two patterns were also detected in many other plant species including rice and cucumber (Supplementary Figure 1).

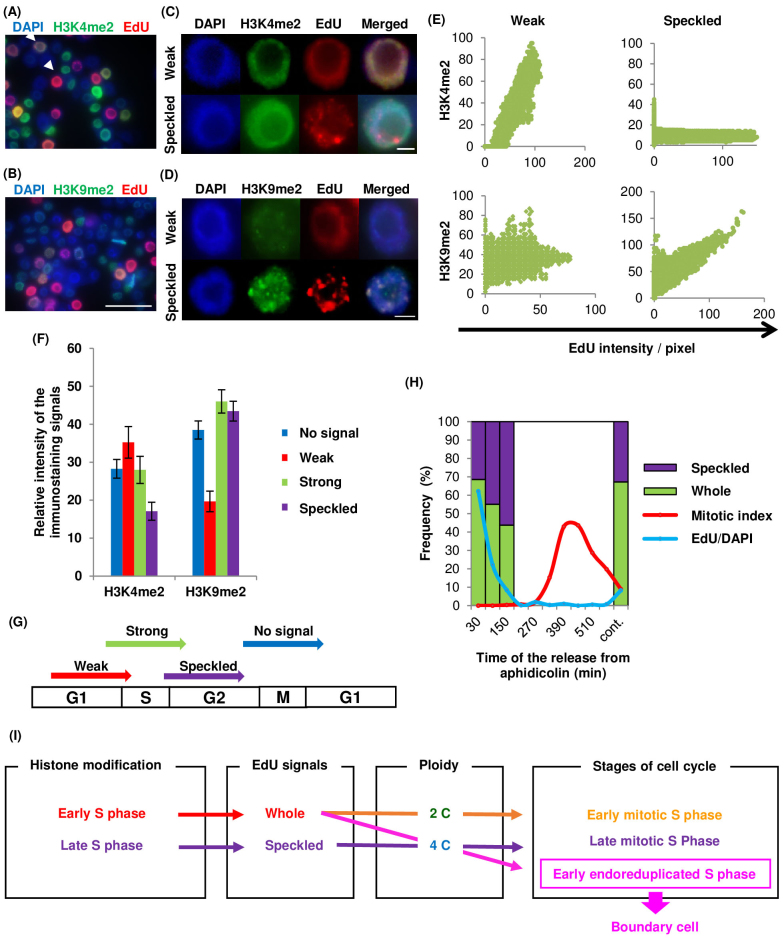

We analysed tobacco BY-2 cultured cells to explore the reasons for these two EdU patterns. These cells have large nuclei and their cell cycle can be synhcronized24,25. Immunostaining was performed using antibodies against the euchromatic marker H3K4me2 to detect early DNA replication and the heterochromatic marker H3K9me226 (Figure 3A, B, C, D); plant heterochromatic regions replicate at late S phase27. The whole pattern could be separated further into strong- and weak-type patterns, depending on the intensity of the EdU signals. The weak EdU signals were five times less intense than the strong ones. The H3K4me2 staining was correlated with weak whole EdU signals, while H3K9me2 staining was correlated with EdU speckled signals (Figure 3C, D, E). When histone modification immunostaining was compared with the intensity of EdU signal patterns, H3K4me2 staining was stronger in nuclei with the weak whole signal pattern, whereas H3K9me2 staining was weaker in such nuclei, compared with those showing other signal patterns (Figure 3F). This result indicated that the weak whole signal and the speckled signal represented early and late DNA replication stages in the nuclei (Figure 3G). To confirm the timing of these signal patterns in nuclei, BY-2 cells were synchronized at S phase using the DNA polymerase inhibitor, aphidicolin, and EdU was added as a pulse treatment at various times after aphidicolin release (Figure 3H). As the nuclei entered S phase after aphidicolin release, the frequency of speckled EdU signals increased. This result confirmed that the weak whole pattern appeared in nuclei at early S phase, and the speckled pattern appeared at late S phase.

Figure 3. Immunostaining of Nicotiana tabacum BY-2 cultured cells and cell-cycle synchronization.

Immunostaining to detect histone modifications in nuclei of Nicotiana tabacum BY-2 cultured cells; (A) H3K4me2, (B) H3K9me2. Arrowheads in (A) indicate weak whole (left top) and strong whole (right bottom) patterned cells. Scale bars = 50 μm. Magnification of weak whole and speckled patterns with (C) H3K4me2 and (D) H3K9me2 staining. Scale bars = 5 μm. (E) Graphs showing relationship between EdU signal intensity and histone modification staining. Vertical and horizontal axes represent intensity of histone modification staining and EdU signals, respectively. (F) Graph of relative H3K4me2 and H3K9me2 staining intensities among the patterns classified as no signal, weak whole, and strong whole EdU signals (n > 50). (G) Model of the EdU signal patterns and timing of EdU incorporation. (H) Synchronization of cell-cycle in BY-2 cultured cells using aphidicolin. Frequency of speckled and whole patterns of EdU signals (purple and green), frequency of EdU-incorporated cells (blue line), and mitotic index (red line). (I) Flow chart of relationships among histone modification, EdU signals, ploidy, and cell cycle stages. Whole and speckled EdU signal patterns indicate early and late S phase, respectively; 4C nuclei with the whole pattern of EdU signals are in the early S phase, and indicate the boundary cells that are located at the starting point of endoreduplication.

DNA replication precedes cell expansion in the root elongation zone

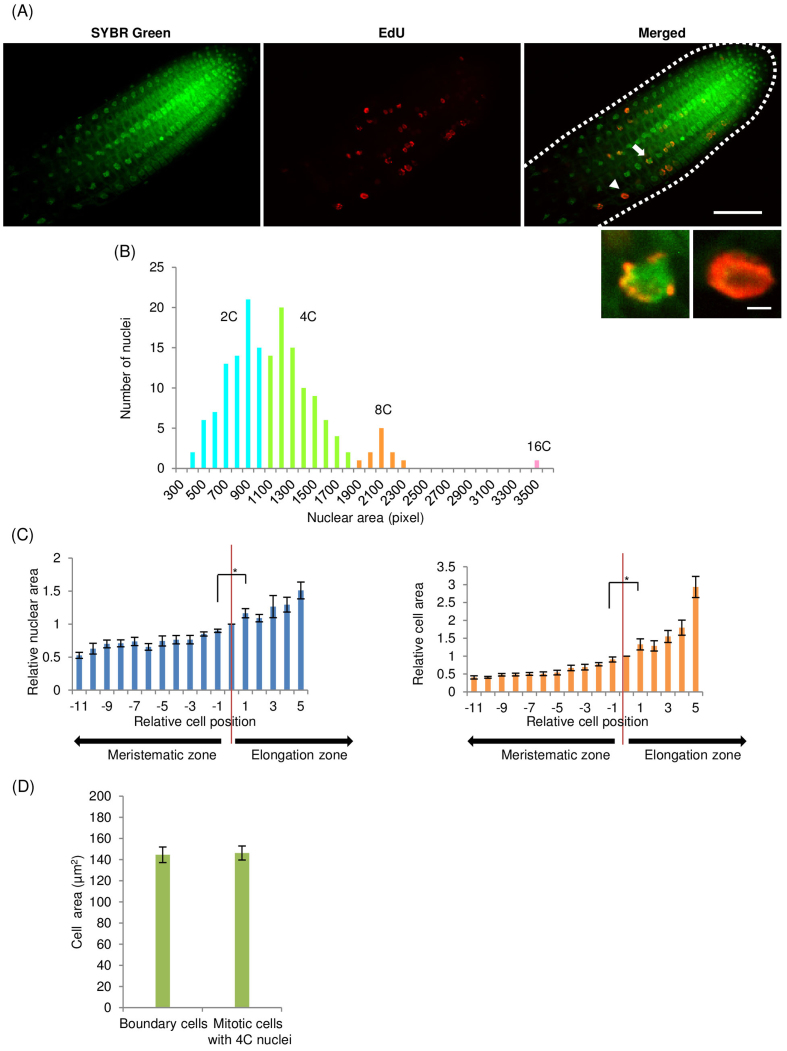

We observed in the synchronized BY-2 cells that a short exposure to EdU enabled classification of 4C nuclei into early and late S phase. Therefore, this finding could be adapted to define cells beginning endoreduplication in the boundary region between meristematic and elongation zones. The 4C nuclei with the whole pattern of EdU signals indicated endoreduplicated cells at early S phase, while 4C nuclei with the speckled signals indicated mitotic cells at late S phase (Figure 3I). We defined the cells with 4C nuclei with the whole pattern of EdU signals as boundary cells. We examined A. thaliana root cells in the boundary region by staining nuclei with SYBR Green and by incorporating EdU (Figure 4A). These analyses revealed a boundary cell at the boundary between the meristematic and elongation zones (arrowhead in Figure 4A). We constructed a histogram of nuclei area, which is proportional to the C value8, for cells in the root meristematic and elongation zones. The histogram showed four peaks, so those nuclei with an area of 1,100–1,900 pixels were defined as 4C nuclei (Figure 4B). Next, the relative cell area was calculated by normalization to the cell area of a boundary cell. We plotted the average relative nuclear area and the average relative cell area, against their position relative to the boundary cell (Figure 4C). The C value of cells and the cell area increased from the meristematic zone to the elongation zone. The cell area of boundary cells was not significantly different from that of mitotic cells with 4C nuclei that were located within five cells of the boundary cell (Figure 4D). Taken together, these results indicated that a greater increase in cell volume occurred after the onset of endoreduplication.

Figure 4. Boundary between root meristematic and elongation zones.

(A) Root meristematic and elongation zones of A. thaliana, stained with SYBR Green (upper left), 1 h incubation with EdU (upper middle), and merged (upper right). Arrowhead shows a boundary cell with 4C nucleus exhibiting the whole pattern of EdU signals, arrow shows a 4C nucleus with speckled pattern. Magnification of 4C nucleus with speckled (lower left) and whole (lower right) patterns. Scale bars = 50 μm (upper right) and 3 μm (lower right). (B) Histogram of nuclei in the root meristematic and elongation zones. Vertical axis is the number of nuclei; horizontal axis is the nuclear area (in pixels). Blue, green, orange, and pink indicate 2C, 4C, 8C, and 16C nuclei, respectively. (C) Relationship between relative cell position and relative nuclear area (left) or relative cell area (right). Relative cell position indicates location of cell relative to boundary cell. Cells at the minus and plus position are in meristematic and elongation zones, respectively. Red lines indicate the boundary cells at zero position (n > 6, * p < 0.05). (D) Comparison between cell areas of the boundary cells and mitotic cells with 4C nuclei (n = 10).

Discussion

There is a proportional relationship between incubation time with EdU and the frequency of EdU-positive nuclei. Therefore, it is possible to reduce the incubation period in EdU to determine the duration of the cell cycle. The duration of the cell cycle becomes longer as the developmental stage advances28. Thus, a short measurement period makes it possible to trace the duration of the cell cycle after germination. The method can also be adapted to other plant tissues, i.e. leaves23 and the SAM29. The duration of the cell cycle in plants has been determined using various methods30, such as labelling with 3H-thymidine30,31 or BrdU31,32,33, by blocking the cell cycle with colchicine34,35, and by kinematic methods with mathematical calculations36. Estimating hypothetical curves of 3H-thymidine incorporation has serious problems, including radioactive decay32. A non-radioactive thymidine analogue, BrdU, allows visualization of DNA replication in roots, but an HCl treatment is required to denature DNA, and immunostaining with the anti-BrdU antibody requires multiple preparation steps to section tissues or prepare protoplasts32. These technical problems make it difficult to estimate the cell cycle dynamics of all cell layers in the root while maintaining its morphology. The duration of the cell cycle in the A. thaliana root 6 days after germination was estimated to be approximately 24 h using the kinematic method37. In contrast to the EdU method, the kinematic method is limited to regions of active cell division. It cannot be adapted to regions without cell division, i.e. elongation and differentiation zones, because it relies on an increase in cell number30. Time-lapse imaging using A. thaliana plants expressing cell wall and nuclear markers with fluorescent proteins demonstrated that the cell cycle duration was 16.6 h38, which is very close to that determined in this study for cells in the meristematic zone of the A. thaliana root. Comparing these results, the EdU method can easily and accurately determine the duration of the cell cycle in plant tissues without introducing fluorescent proteins fused to cell cycle markers.

Our method revealed that the cell cycle in the elongation zone is longer than that in the meristematic zone in A. thaliana roots. Generally, the duration of cell cycle becomes longer as the developmental stage advances39. Because the elongation zone sequentially changes into a differentiation zone, the slower cell cycle in the elongation zone is consistent with the developmental process in the root. Our results showed that the endoreduplication cycle acts upstream of rapid cell expansion in the root boundary region. Endoreduplication was shown to be strongly correlated with cell growth of trichome and pavement cells in the epidermis of leaves10,40 and with expansion of giant cells in the epidermis of sepals41. Those reports could not confirm whether endoreduplication and rapid cell expansion occurred first in such cells, but the identity of the cells was established before the cell cycle transition40. This is similar to the case in roots, in which cell identity is determined at the stem cell niche in the apical region of the meristematic zone. However, recent studies demonstrated that the onset of endoreduplication with repression of mitosis also plays an important role in determining the cell fate of trichome cells42 and giant cells43. Trichome cells and giant cells are dispersed among the surrounding mitotic cells of the epidermis. In roots, however, orderly files of radicle cells sequentially become a part of the elongation zone through the boundary region. Endoreduplication has no effect on cell identity in roots, at least for cells in the elongation zone. It is plausible that the relationship between endoreduplication and cell expansion in the cell developmental process is coordinated by different mechanisms in leaves/sepals and roots.

Endoreduplication is regulated by proteins responsible for DNA replication and cell cycle control16. Overexpression of CDC6 (or CDT1a), which is a subunit of the prereplicative complex essential to initiate DNA replication, induces both mitosis and endoreduplication44. E2Fa, a promoter, and RBR, an inhibitor, are responsible for the transition from G1 to S phase. Overexpression of E2Fa or suppression of RBR, which contribute to the upregulation of S phase-specific genes, promotes both mitosis and endoreduplication12. These results suggest that there is little difference in DNA replication between the mitotic cell cycle and endoreduplication cycle. The conversion from mitosis to endoreduplication requires the suppression of mitotic entry after DNA replication, i.e., mitotic CDK inactivation through ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis12. Taken together, these facts and observations indicate that the pathway to induce rapid cell expansion is closely related to the inhibition of mitotic entry. The cell wall expansion that occurs during cell enlargement requires synthesis of polysaccharide polymers and cellulose microfibrils; however, the signalling pathway from mitotic repression to metabolic activation of cell wall components is completely unknown. Further research is required to identify an inducer of rapid cell expansion that activates metabolic activity after the mitosis-to-endoreduplication switch.

Methods

Plant materials

The following materials were used in this study: Arabidopsis thaliana (Nossen); BY-2 cultured cells: (Nicotiana tabacum cv. Bright Yellow-2); cucumber: Cucumis sativus “Tokiwajibai” (Ataria Noen, Japan); rice: Oryza sativa (Nipponbare).

Imaging procedures

Seedlings were placed in liquid medium (1 × MS, 1% sucrose, and 10 μM EdU in Click-iT component A (Invitrogen)) or sterilized water (C. sativus and O. sativa) and incubated with EdU at 22°C under continuous light. EdU was detected following the manufacturer's instructions for Click-iT, and stained with 5,000-times diluted SYBR Green I (LONZA) for 4 min. After three washes with PBS, the samples were mounted with mounting medium (97% 2,2′-thiodiethanol (Sigma), 3% 1 × PBS, and 2.5% (g/V) n-propyl gallate)45. Samples were observed under a confocal laser microscope (IX 81, Olympus) equipped with a CCD camera (Cool Snap HQ2, Nippon Roper). Images were analysed with ImageJ software.

Cell cycle duration

Images were acquired as z-stack images and clearly stained images were chosen to count nuclei. Meristematic and elongation zones were designated according to the nearest distance between the edges of nuclear areas of adjacent cells in each cell file. The distance at the apex end of the elongation zone is more than twice that at the basal end of the meristematic zone. These values were obtained for each seedling and averaged over time. Then, the ratio of incorporated EdU (EdU-incorporated nuclei divided by SYBR Green-stained nuclei multiplied by 100) was plotted against the EdU incorporation time for cells in the meristematic zone (Figure 1C) and for cells in the elongation zone (Figure 1D). These plots were least squared and the time for all nuclei to incorporate EdU was estimated by the linear approximation formula:

where “a” is the slope and “b” is the x intercept of the linear approximation formula.

The increasing rate of EdU-positive nuclei against incubation time with EdU can be calculated by the formula ΔN/Δt, where N is the frequency of EdU-positive nuclei. When the total number of nuclei is S and S is sufficiently large, the increasing rate of EdU-positive nuclei reflects the cell cycle rate, assuming that all cells in the field of observation have the same cycle length, and that each cell cycle stage is random (Figure 2). In addition, the cell cycle rate is indicated by the formula, dL/dt, where L is the stage of the cell cycle, Thus, we have the following equation:

The relationship of (1) is set. From the plot of the frequency of EdU-positive nuclei vs. EdU incubation time, a linear approximation gives the following formula:

Integration of right side of the formula (1) gives (3):

where b = c, N(t) = L(t) is set. One cell cycle span coincides with 0 < N(t) < 100, i.e. −b/a < t < 100/a. Thus, cell cycle duration can be calculated using the following formula:

Sequenced nuclei counting

We used samples of A. thaliana incubated with EdU for 1 and 3 h for this analysis. Sequences of 2, 4, 6, and 8 nuclei were counted in the meristem region, which was defined in the cell cycle duration experiment.

BY-2 EdU incorporation, immunostaining, and synchronization

BY-2 cells were cultured on a rotary shaker at 130 rpm at 27°C in the dark24. After 2 days, a 15 mL aliquot of BY-2 cells was centrifuged at 800 × g and 13 mL supernatant was discarded. Then, 2 μL 10 mM EdU solution was added (final concentration 2 μM) and the cells were incubated on a reciprocal shaker at 130 rpm at 27°C in the dark for 6 h. The cells were then centrifuged at 800 × g and the supernatant was discarded. Enzyme solution (2% Cellulase ONOZUKA RS, 0.1% Pectolyase Y-23 in 0.45 M mannitol, pH 5.5) was added and the cells were incubated on a reciprocal shaker at 130 rpm at 27°C in the dark for 90 min. After centrifugation at 800 × g, the supernatant was discarded and the cells were washed with 6 M mannitol. The cells were fixed with PBS with 4% paraformaldehyde and washed with PBS with 3% BSA. EdU was detected as described under ‘Imaging procedures'. After EdU detection, the cells were centrifuged at 3,600 × g for a few seconds and the supernatant was discarded. The cells were incubated with 1% blocking reagent (Roche) in PBS for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. Primary antibody (anti-H3K4me2 or anti-H3K9me2; Abcam) diluted 100 times with 1% blocking reagent in PBS was added and the cells were incubated overnight at 4°C. The samples were washed twice with polyoxyethylene sorbitan monolaurate (Tween 20) in PBS for 10 min with shaking on a reciprocal shaker at 70 rpm and then incubated with 1% blocking reagent in PBS for 30 min at room temperatures in the dark. Secondary antibody (anti-rabbit Alexa Fluora 488; Invitrogen) diluted 100 times with 1% blocking reagent in PBS was added and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 1 h in the dark. The samples were washed twice with 0.05% Tween 20 in PBS for 10 min with shaking at 70 rpm. The first wash solution contained DAPI (4 μg/mL) and the samples were washed with deionized water three times. The samples were observed under a fluorescence microscope (BX53, Olympus) and images were acquired with a DP72 camera (Olympus).

BY-2 cells were synchronized in a single step as described by Kumagai-Sano et al25. A 10-mL aliquot of synchronized cells was centrifuged at 800 × g and 8 mL of the supernatant was discarded. Then, 2 μL 10 mM EdU was added at 30, 90, 150, 210, 270, 330, 390, 450, 510, and 570 min after aphidicolin release and the cells were cultured on a reciprocal shaker at 130 rpm at 27°C in the dark for 30 min. The cells were centrifuged at 800 × g and the supernatant was discarded. The cells were then fixed with 1 mL of PBS with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min. EdU detection was performed as described under ‘Imaging procedures'. After EdU detection, the cells were stained with DAPI (4 μg/mL) and observed under a fluorescence microscope (BX53, Olympus). Images were acquired with a DP72 digital camera (Olympus) and analysed with ImageJ software.

Determination of the boundary of the root meristem and elongation zone

We used seedlings of A. thaliana, incubated with EdU for 1 h, for this experiment. The seedlings were stained with SYBR Green. The areas of the nuclei and the cells were measured from the SYBR Green signals and from transmission images.

Author Contributions

K.H. and S.M. designed experiments and wrote the paper. K.H. performed experiments, cultured plant cells, and analysed imaging data. J.H. performed some experiments on tobacco BY-2 cells. S.M. supervised the project. All authors contributed through discussion and reviewed the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

EdU signal patterns in Cucumis sativus and Oryza sativa.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a SENTAN grant from the Japan Science and Technology Agency, a Grant-in-Aid for X-ray Free Electron Laser Priority Strategy Program (MEXT), and grants from MEXT/JSPS KAKENHI (25113002, 23370029, 23120518, 231012027).

References

- Matz M. V., Frank T. M., Marshall N. J., Widder E. A. & Johnsen S. Giant deep-sea protist produces bilaterian-like traces. Curr Biol 18, 1849–1854 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall W. F. et al. What determines cell size? BMC Biol 10, 101 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukaya H. Organ shape and size: a lesson from studies of leaf morphogenesis. Curr Opin Plant Biol 6, 57–62 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conlon I. & Raff M. Size control in animal development. Cell 96, 235–244 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukaya H. Controlling size in multicellular organs: Focus on the leaf. Plos Biology 6, 1373–1376 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendell J. E., Clements K. D., Choat J. H. & Angert E. R. Extreme polyploidy in a large bacterium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 6730–6734 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zielke N. et al. Control of Drosophila endocycles by E2F and CRL4CDT2. Nature 480, 123–127 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox D. & Duronio R. Endoreplication and polyploidy: insights into development and disease. Development 140, 3–12 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breuer C., Ishida T. & Sugimoto K. Developmental control of endocycles and cell growth in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol 13, 654–660 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melaragno J. E., Mehrotra B. & Coleman A. W. Relationship between endopolyploidy and cell size in epidermal tissue of arabidopsis. Plant Cell 5, 1661–1668 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berckmans B. et al. Light-dependent regulation of DEL1 Is determined by the antagonistic action of E2Fb and E2Fc. Plant Physiol 157, 1440–1451 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi S. et al. Programmed induction of endoreduplication by DNA double-strand breaks in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 10004–10009 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandran D., Inada N., Hather G., Kleindt C. & Wildermuth M. Laser microdissection of Arabidopsis cells at the powdery mildew infection site reveals site-specific processes and regulators. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 460–465 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perilli S., Di Mambro R. & Sabatini S. Growth and development of the root apical meristem. Curr Opin Plant Biol 15, 17–23 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Veylder L., Larkin J. & Schnittger A. Molecular control and function of endoreplication in development and physiology. Trends in Plant Sci 16, 624–634 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga S. et al. New insights into the dynamics of plant cell nuclei and chromosomes. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 305, 253–301 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petricka J., Winter C., Benfey P. & Merchant S. Control of Arabidopsis root development. Annual Review of Plant Biology 63, 563–590 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beemster G., Fiorani F. & Inze D. Cell cycle: the key to plant growth control? Trends in Plant Sci 8, 154–158 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traas J., Hulskamp M., Gendreau E. & Hofte H. Endoreduplication and development: rule without dividing? Curr Opin Plant Biol 1, 498–503 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondorosi E. & Kondorosi A. Endoreduplication and activation of the anaphase-promoting complex during symbiotic cell development. FEBS Lett 567, 152–157 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salic A. & Mitchison T. J. A chemical method for fast and sensitive detection of DNA synthesis in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 2415–2420 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotogány E., Dudits D., Horváth G. V. & Ayaydin F. A rapid and robust assay for detection of S-phase cell cycle progression in plant cells and tissues by using ethynyl deoxyuridine. Plant Methods 6, 5 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichihashi Y. et al. Key proliferative activity in the junction between the leaf blade and leaf petiole of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 157, 1151–1162 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata T., Nemoto Y. & Hasezawa S. Tobacco BY-2 cell-line as the HeLa-cell in the cell biology of higher-plants. Int Rev Cyt 132, 1–30 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai-Sano F., Hayashi T., Sano T. & Hasezawa S. Cell cycle synchronization of tobacco BY-2 cells. Nature Protocols 1, 2621–2627 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costas C. et al. Genome-wide mapping of Arabidopsis thaliana origins of DNA replication and their associated epigenetic marks. Nat Struct Mol Biol 18, 395–400 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D. H. et al. CTCF-dependent chromatin bias constitutes transient epigenetic memory of the mother at the H19-Igf2 imprinting control region in prospermatogonia. PLoS Genet 6, e1001224, 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001224 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asl L. K. et al. Model-based analysis of Arabidopsis leaf epidermal cells reveals distinct division and expansion patterns for pavement and guard cells. Plant Physiol 156, 2172–2183 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katharina S., Swathi K., Paul S., Max B. & Robert S. JAGGED controls growth anisotropy and coordination between cell size and cell cycle during plant organogenesis. Curr Biol 22, 1739–1746 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorani F. & Beemster G. T. Quantitative analyses of cell division in plants. Plant Mol Biol 60, 963–979 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quastler H. & Sherman F. G. Cell population kinetics in the intestinal epithelium of the mouse. Exp Cell Res 17, 420–438 (1959). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster P. L. & Macleod R. D. Characteristics of root apical meristem cell-population kinetics - A review of analyses and concepts. Environ Exp Bot 20, 335–358 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- Lucretti S. et al. Bivariate flow cytometry DNA/BrdUrd analysis of plant cell cycle. Methods Cell Sci 21, 155–166 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clowes F. Estimation of growth fractions in meristems of Zea mays. L. Ann Bot 40, 933–938 (1976). [Google Scholar]

- Kinsman E. et al. Elevated CO2 stimulates cells to divide in grass meristems: a differential effect in two natural populations of Dactylis glomerata. Plant Cell Environ 20, 1309–1316 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Erickson R. O. modeling of plant growth. Plant physiolgy 27, 407–434 (1976). [Google Scholar]

- Beemster G. T. & Baskin T. I. Analysis of cell division and elongation underlying the developmental acceleration of root growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol 116, 1515–1526 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campilho A., Garcia B., Toorn H. V., Wijk H. V. & Scheres B. Time-lapse analysis of stem-cell divisions in the Arabidopsis thaliana root meristem. Plant J 48, 619–627 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan D. O. The cell cycle: principles of control. New Science Press 297 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Larkin J., Brown M. & Schiefelbein J. How do cells know what they want to be when they grow up? Lessons from epidermal patterning in Arabidopsis. Annual Review of Plant Biology 54, 403–430 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeder A. et al. Variability in the control of cell division underlies sepal epidermal patterning in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plos Biology 8, e1000367 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000367 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roodbarkelari F. et al. CULLIN 4-RING FINGER-LIGASE plays a key role in the control of endoreplication cycles in Arabidopsis trichomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeder A. H., Cunha A., Ohno C. K. & Meyerowitz E. M. Cell cycle regulates cell type in the Arabidopsis sepal. Development 139, 4416–4427 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierre C. The Arabidopsis cell division cycle. American society of plant biologists 7 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staudt T., Lang M. C., Medda R., Engelhardt J. & Hell S. W. 2,2′-thiodiethanol: a new water soluble mounting medium for high resolution optical microscopy. Microsc Res Tech 70, 1–9 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

EdU signal patterns in Cucumis sativus and Oryza sativa.