Abstract

Background/Aims

Relapse has been reported after stopping nucleos(t)ide (NUC) therapy in the majority of chronic HBeAg negative hepatitis patients. However, the ideal treatment duration of HBeAg negative chronic hepatitis B (CHB) is not well known. We investigated the frequency of relapse in HBeAg negative CHB patients receiving NUC therapy.

Methods

The NUC therapy was discontinued at least 3 times undetectable level of HBV DNA leave 6 months space in 45 patients. Clinical relapse was defined as HBV DNA >2,000 IU/mL and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or aspartate aminotransferase (AST) >2 times of upper limit of normal range. Virological relapse was defined as HBV DNA >2,000 IU/mL.

Results

Clinical relapse developed in 16 (35.6%) and 24 (53.3%) patients after stopping therapy at 6 months and 12 months off therapy, respectively. Virological relapse developed 22 (48.9%) and 33 (73.3%) patients at 6 months and 12 months off therapy. The factors such as age, gender, cirrhosis, baseline AST, ALT, HBV DNA levels, treatment duration, and consolidation duration were analyzed to investigate the predictive factors associated with 1 year sustained response. Of these factors, cirrhosis (86.1% in CHB, 22.2% in LC) was significantly associated with 1 year virological relapse rate. Baseline HBV DNA and total treatment duration tended to be associated with virological relapse.

Conclusions

Virological relapse developed in the majority (73.3%) of HBeAg negative CHB patients and clinical relapse developed in the half (53.3%) of patients at 1 year off therapy. Cirrhosis may be associated with the low rate of virological relapse.

Keywords: Chronic hepatitis B, Durability, Nucleos(t)ide analogue

INTRODUCTION

About 400 million people worldwide are chronically infected with the hepatitis B virus (HBV).1,2 The prevalence of HBeAg negative chronic hepatitis B (CHB) is increasing in the last 3 decades worldwide.3-6 Most HBeAg negative CHB has been shown to be associated with mutations in the precore or core promoter regions of the HBV genome that unable to produce HBeAg.4-6 HBeAg negative CHB patients tend to be more severe and progressive disease pattern with very rare spontaneous remissions, compared with HBeAg positive CHB.6,7 The HBsAg seroconversion is only achieved in small portion of CHB patients with nucleos(t)ide (NUC) treatments. The clinician's realistic goal is a suppression of HBV DNA level, alternatively.8

It is important to know when the NUC can be stopped safely, because NUC antiviral resistance might be concerned with its duration.9,10 Asia pacific association for study of liver (APASL) guideline suggested that if undetectable HBV-DNA has been documented on 3 occasions 6 months apart, discontinuation of treatment can be considered.9 We investigated the frequency of relapse in HBeAg negative CHB patients receiving NUC therapy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Subjects

This study included 45 patients with HBeAg negative CHB who started NUC therapy from July 2003 to February 2008 at Ajou University Hospital in Korea. The NUC therapy was discontinued at least 3 times undetectable level of HBV DNA leave 6 months space, as suggested by asia pacific association for study of liver (APASL) guideline. They discontinued the NUC therapy from May 2007 to March 2011. 33 patients were first line treatment and 12 patients were changed their agents (25 with entecavir, 14 with lamivudine, 6 with adefovir). All patients had followed up at least 1 year after stopping NUC therapy. And the mean follow up period was 20.12 (±10.87 months). This study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Research at Ajou Univeirsity Hospital.

Methods

The patients were monitored their symptoms and laboratory tests every 3 months. The test included serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and HBV DNA level. The initial laboratory test included also platelet count, serum albumin level, and international normalized ratio (INR) to differentiate liver cirrhosis patients. The abdominal ultrasonography was performed. Clinical relapse was defined as HBV DNA level of more than 2,000 IU/mL plus at least one of the ALT, AST is of more than 2 times of upper limit of normal range. Virological relapse was defined as only HBV DNA level of more than 2,000 IU/mL regardless of their ALT and AST level. The liver cirrhosis was defined when their abdominal ultrasonography represent surface nodularity and/or when their laboratory test satisfied one of 3 conditions without infectious states (platelet <100,000/uL, albumin <3.5 g/dL, INR >1.3).11

Serum ALT and AST were measured using standard procedures. HBeAg and anti-HBeAb were detected with the Abbott immunoassay system (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, USA) and HBV DNA was quantified with real time PCR by COBAS TaqMan assay (Roche Diagnostics, Branchburg, NJ, USA; lower limit, 50 copies/mL).

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed either as mean±standard deviation. Statistical analyses were conducted using Student's t-test, Mann Whitney U-test, and the chi-square test. Statistical analysis was performed using version 18.0, SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Data were considered to be statistically significant with P<0.05.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

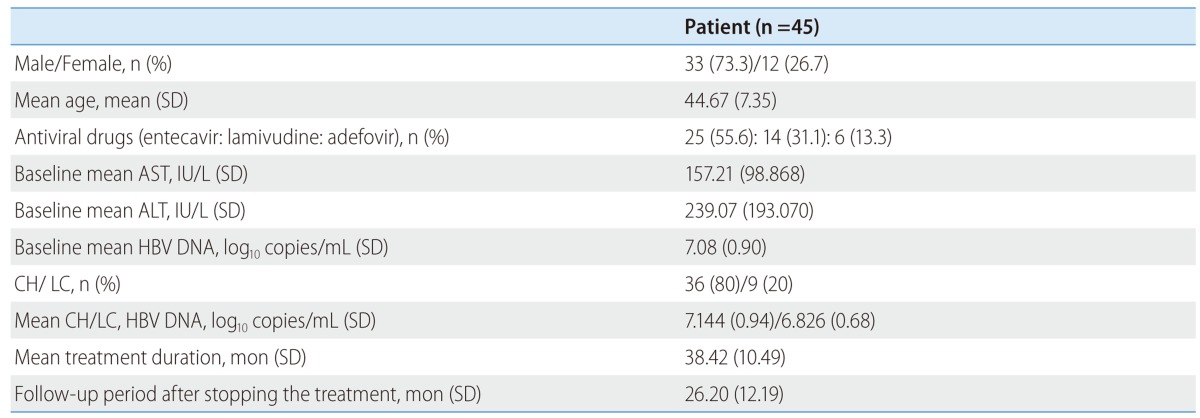

The baseline characteristics of the 45 patients are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the patients was 44.67±7.35, and 33 (73.3%) patients were male. Patients received NUC therapy; entecavir (n=25), lamivudine (n=14), adefovir (n=6). The mean baseline serum ALT was 239.07±193.07 IU/L and serum AST was 157.21±98.87 IU/L. The mean baseline serum HBV DNA was 7.08±0.90 log10 copies/mL. Thirty six patients had CHB, 9 patients had cirrhosis. The mean treatment duration was 38.42±10.49 months (18 months to 87 months). The mean follow-up period was 20.12±10.87 months.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients

SD, standard deviation; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; HBV, Hepatitis B virus; LC, Liver cirrhosis; CH, chronic hepatitis.

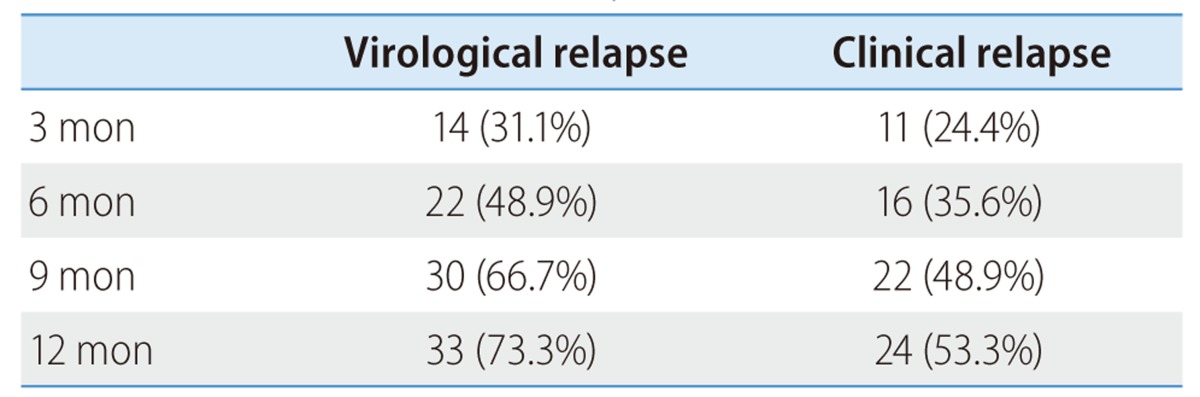

Frequency of virological and clinical relapse after cessation of NUC therapy

The virological and clinical relapse rates at 6 months and 12 months off-therapy was shown in Table 2. Virological relapse rate were 48.9% and 73.3% in each of periods. Clinical relapse rate were 35.6% and 53.3% in that periods. The cumulative relapse rates after NUC therapy were presented at 3 months interval, as shown in Table 2. Both relapse rates increased until 1 year off-therapy and the relapse rate had plateau state thereafter.

Table 2.

Virological and clinical relapse rate at 3 months intervals

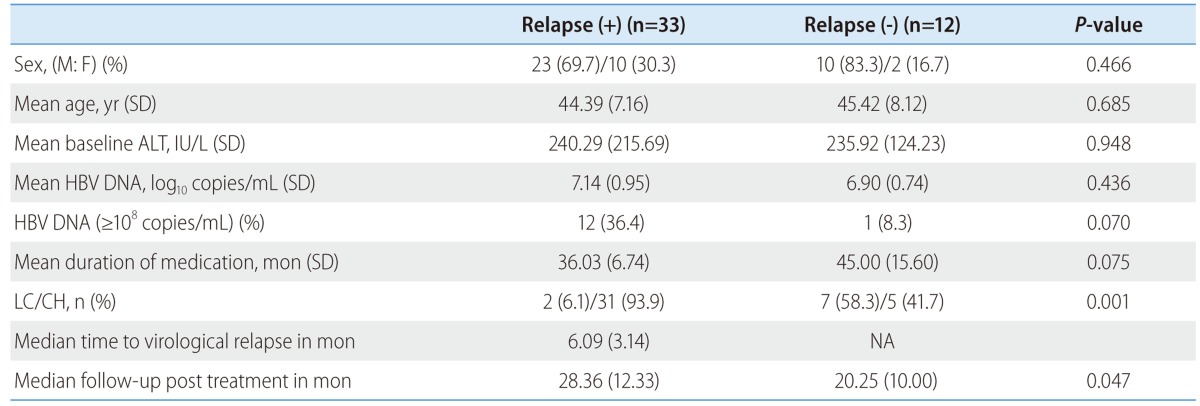

Factors related to virological relapse after cessation of NUC therapy

Factors associated with virological relapse after cessation of NUC therapy were analyzed. Table 3 showed the characteristics between virological relapsers and non-virological relapsers after off-treatment of NUC therapy. In a univariate analysis significant predictive factor for virological relapse was liver cirrhosis. Virological relapse was significantly low in cirrhotic patients (6.1% vs. 58.3%). The patients with HBV DNA ≥108 copies/mL tended to develop relapse more frequently than the patients with HBV DNA <108 copies/mL (38.7% vs. 8.3%, P-value: 0.070). Long treatment duration tended to be associated with low frequency of virological relapse (36.03±6.74 months vs. 45.00±15.60 months, P-value: 0.077). There were no differences in sex, age, mean baseline HBV DNA and baseline ALT and AST. Subgroup analysis of CHB patients showed no significant differences in relapser and non-relapser group.

Table 3.

Comparison of patients with and without virological relapse within 12 months after stopping treatment in 45 HBeAg negative patients

SD, standard deviation; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; HBV, Hepatitis B virus; LC, Liver cirrhosis; NA, Not available.

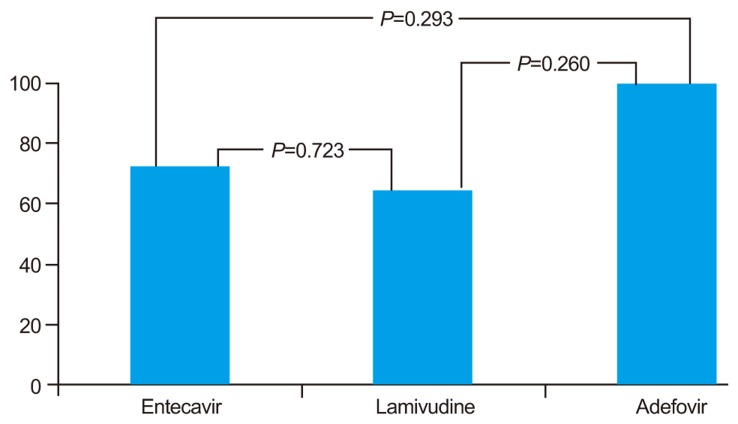

The Figure 1 showed the virological relapse rate after 12 months off-therapy according to the kind of NUC used for treatment. There were no significant differences among 3 patients groups 72% (18/25) for entecavir, 64.29% (9/14) for lamivudine, 100% (6/6) for adefovir respectively.

Figure 1.

Virological relapse rate at 12 months after treatment withdrawal according to the kind of nucleos(t)ides.

DISCUSSION

NUC treatment is effective in the suppression of HBV replication in HBeAg negative CHB.12 However, withdrawal of NUC therapy is associated with relapse in most of patients within 1 year of NUC treatment. Previous studies of 1 year treatment with lamivudine and entecavir showed post withdrawal relapse rates of 87% and 97%, respectively.13,14

Several NUC therapies, for periods longer than 1 year, have been tried to investigate the off-therapy durability in HBeAg negative CHB patients. The study of a 2-year course of lamivudine showed 50% of virological relapse and 30% of clinical relapse at 18 months off-therapy in HBeAg negative CHB patients.15 Another study showed cumulative virological relapse rates at months 6 and 12 were 26.2% and 43.6%, respectively in patients receiving lamivudine for at least 24 months.16 It has been reported that 55% of patients have remained sustained remission at years 5 off-therapy in HBeAg negative CHB patients receiving adefovir for 4-5 years.17 These results suggested that a sustained remission can be achieved in some portions of HBeAg negative CHB patients with longer duration of NUC treatment.

The APASL recommend discontinuation of treatment if HBV DNA remains undetectable by PCR on 3 separate occasions 6 months apart in HBeAg negative CHB patients receiving NUC.9 We evaluated the stopping rule of the APASL in HBeAg (-) CHB patients receiving entecavir. In the present study, virological relapse rates were found to be 48.9% and 73.3% at 6 and 12 months off-treatment, respectively. Thirty five and 53.3% of patients showed clinical relapse at 6 and 12 months off-treatment, respectively. A study conducted in China showed that cumulative virological relapse rates at 12 and 24 months were 43.6% and 49.7% in patients receiving lamivudine, respectively.16 Another study recently conducted in Taiwan showed that clinical relapse rates were 27.8% and 53.2% at 6 and 12 months off-treatment in patients receiving entecavir.18 The relapse rate of this study of Korean patients was comparable to that of Taiwan study. In the previous study of Korean patients, the durability of response after cessation of 24 months course lamivudine therapy were 79.1% and 64.0% at months 12 and 24, respectively, showing a low relapse rate in comparison with our study.19 In that study,19 HBV DNA were measured by the hybrid capture assay, which is less sensitive than a PCR-based assay. This limitation may result in overestimation of durability of response. We attempted to find out the factors associated with relapse. Relapse rate was found to be significantly low in cirrhotic patients. The patients with baseline HBV DNA ≥108 copies/mL tended to develop relapse more frequently than those with HBV DNA <108 copies/mL, and longer treatment duration tended to be associated with low relapse rate. The previous studies reported that age was the only factor associated with relapse.16,20 In contrast to our study, a study of Korean patients reported that the proportion of liver cirrhosis was significantly higher in relapsers than non-relapsers.19 But the number of our study was insufficient to conclude liver cirrhosis associated with low relapse rate. Large scale studies are needed to clarify this result. In a recent study, pretreatment HBV DNA <106 copies/mL was reported to be the only independent factors for 1-year sustained response.18 These studies indicated that further studies are needed to validate the predicting factor for relapse in HBeAg negative CHB.

In conclusion, at 1 year off treatment the virological relapse developed in 73.3% of patients receiving NUC treatment and clinical relapse developed in 53.3% of NUC treated patients who met the stopping rule of the APASL for HBeAg negative CHB. Liver cirrhosis might be associated with the low frequency of virological relapse. Long treatment duration and low baseline HBV DNA level (<108 copies/mL) tended to be associated with low frequency of virological relapse.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI10C2020).

Abbreviations

- ADV

adefovir

- ALT

Alanine aminotransferase

- APASL

asia pacific association for study of liver

- AST

Aspartate aminotransferase

- CHB

chronic hepatitis B

- ETV

entecavir

- HBV

Hepatitis B virus

- INR

international normalized ratio

- IU

international unit

- LAM

lamivudine

- LC

Liver cirrhosis

- NUC

Nucleos(t)ide

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Lai CL, Ratziu V, Yuen MF, Poynard T. Viral hepatitis B. Lancet. 2003;362:2089–2094. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee WM. Hepatitis B virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1733–1745. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199712113372406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Funk ML, Rosenberg DM, Lok AS. World-wide epidemiology of HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B and associated precore and core promoter variants. J Viral Hepat. 2002;9:52–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2002.00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manesis EK. HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B: from obscurity to prominence. J Hepatol. 2006;45:343–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Papatheodoridis GV, Hadziyannis SJ. Diagnosis and management of pre-core mutant chronic hepatitis B. J Viral Hepat. 2001;8:311–321. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2001.00303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hadziyannis SJ, Vassilopoulos D. Hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2001;34:617–624. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.27834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Papatheodoridis GV, Hadziyannis SJ. Review article: current management of chronic hepatitis B. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:25–37. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yuen MF, Lai CL. Treatment of chronic hepatitis B: Evolution over two decades. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26(Suppl 1):138–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liaw YF, Leung N, Kao JH, Piratvisuth T, Gane E, Han KH, et al. Asian-Pacific consensus statement on the management of chronic hepatitis B: a 2008 update. Hepatol Int. 2008;2:263–283. doi: 10.1007/s12072-008-9080-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee M, Keeffe EB. Hepatitis B: modern end points of treatment and the specter of viral resistance. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2011;40:495–505. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee HS, Kim JK, Cheong JY, Han EJ, An SY, Song JH, et al. Prediction of compensated liver cirrhosis by ultrasonography and routine blood tests in patients with chronic viral hepatitis. Korean J Hepatol. 2010;16:369–375. doi: 10.3350/kjhep.2010.16.4.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim SS, Cheong JY, Cho SW. Current nucleos(t)ide analogue therapy for chronic hepatitis B. Gut Liver. 2011;5:278–287. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2011.5.3.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santantonio T, Mazzola M, Iacovazzi T, Miglietta A, Guastadisegni A, Pastore G. Long-term follow-up of patients with anti-HBe/HBV DNA-positive chronic hepatitis B treated for 12 months with lamivudine. J Hepatol. 2000;32:300–306. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shouval D, Lai CL, Chang TT, Cheinquer H, Martin P, Carosi G, et al. Relapse of hepatitis B in HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B patients who discontinued successful entecavir treatment: the case for continuous antiviral therapy. J Hepatol. 2009;50:289–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fung SK, Wong F, Hussain M, Lok AS. Sustained response after a 2-year course of lamivudine treatment of hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B. J Viral Hepat. 2004;11:432–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2004.00556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu F, Wang L, Li XY, Liu YD, Wang JB, Zhang ZH, et al. Poor durability of lamivudine effectiveness despite stringent cessation criteria: a prospective clinical study in hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:456–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hadziyannis S, Sevastianos V, Rapti I. Outcome of HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B (CHB) 5years after discontinuation of long term adefovir dipivoxil (ADL) treatment. J Hepatol. 2009;50(Suppl 1):S9–S10. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jeng W, Sheen I, Chen Y, Chu C, Hsu CW, Chien R, et al. Off therapy durability in chronic hepatitis B e antigen negative patients treated with entecavir. Hepatology. 2011;54(Suppl 1):1014A. doi: 10.1002/hep.26549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paik YH, Kim JK, Kim do Y, Park JY, Ahn SH, Han KH, et al. Clinical efficacy of a 24-months course of lamivudine therapy in patients with HBeAg negative chronic hepatitis B: a long-term prospective study. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25:882–887. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2010.25.6.882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ha M, Zhang G, Diao S, Lin M, Sun L, She H, et al. A prospective clinical study in hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B patients with stringent cessation criteria for adefovir. Arch Virol. 2012;157:285–290. doi: 10.1007/s00705-011-1163-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]