Abstract

Pseudothrombocytopenia remains a challenge in the haematological laboratory. The pre-analytical problem that platelets tend to easily aggregate in vitro, giving rise to lower platelet counts, has been known since ethylenediamine-tetra acetic acid EDTA and automated platelet counting procedures were introduced in the haematological laboratory. Different approaches to avoid the time and temperature dependent in vitro aggregation of platelets in the presence of EDTA were tested, but none of them proved optimal for routine purposes. Patients with unexpectedly low platelet counts or flagged for suspected aggregates, were selected and smears were examined for platelet aggregates. In these cases patients were asked to consent to the drawing of an additional sample of blood anti-coagulated with a magnesium additive. Magnesium was used in the beginning of the last century as anticoagulant for microscopic platelet counts. Using this approach, we documented 44 patients with pseudothrombocytopenia. In all cases, platelet counts were markedly higher in samples anti-coagulated with the magnesium containing anticoagulant when compared to EDTA-anticoagulated blood samples. We conclude that in patients with known or suspected pseudothrombocytopenia the magnesium-anticoagulant blood samples may be recommended for platelet counting.

Keywords: platelet aggregation, pseudothrombocytopenia, anticoagulation, magnesium, EDTA, citrate

Enumeration and differentiation of circulating blood cells is performed in the haematological laboratory using appropriately anticoagulated whole blood samples. With the introduction of commercially available blood-collecting systems, salts of ethylenediamine-tetra acetic acid (EDTA) either as di-sodium, di-potassium or tri-potassium salt, are the anticoagulants of choice, and recommended by the International Council for Standardization in Haematology (1993). EDTA chelates divalent cations including calcium, thus avoiding coagulation and stabilizing the sample for subsequent haematological analysis (Banfi et al, 2007).

The use of EDTA is generally accepted to be safe and reliable for obtaining full blood counts. In addition, EDTA salts are compatible with the standard staining protocols for blood smears. One drawback of EDTA salts is a time-dependent osmotic effect, leading to increasing mean cellular volume (MCV) of red blood cells (RBC). If EDTA-anticoagulated samples are not analysed within 24 h, this might lead to misinterpretation, e.g. false high haematocrit values (Robinson et al, 2004).

Much more critical and of proven diagnostic relevance, is the rare occurrence of false low platelet counts in the presence of EDTA, so-called pseudothrombocytopenia (PTCP) (Shreiner & Bell, 1973). Platelet aggregates may be misclassified by haematological analysers as leucocytes and therefore a false high white blood cell (WBC) count may result and escape interpretation as pseudoleucocytosis (Solanki & Blackburn, 1983). PTCP has been shown to be a time- and temperature-dependent phenomenon. Therefore, direct sampling and immediate analysis results in higher platelet counts compared to those obtained after delay. PTCP and recommendations for its prevention were recently reviewed in detail (Lippi & Plebani, 2012).

Although EDTA was introduced in the haematological laboratory in the 1950s (Proesche, 1951), the first report of EDTA-induced platelet aggregation was not reported until 1969 (Gowland et al, 1969). A number of studies notwithstanding, the pathophysiology of abnormal platelet aggregation in the presence of EDTA is not fully understood. In selected cases of EDTA-induced PTCP, blood was recollected using citrate or heparin, but in vitro aggregation was still present (Schrezenmeier et al, 1995).

Before the introduction of EDTA salts, magnesium salts were used as an anticoagulant for sampling capillary blood for microscopic platelet enumeration, as communicated in a widely respected laboratory handbook in the early 1930s (Lenhartz & Meyer, 1934). However, the anti-aggregatory properties of magnesium were forgotten after the introduction of EDTA as an anticoagulant in the haematological laboratory.

These historical accounts inspired us to start a multicentre study using manufactured blood sampling tubes anticoagulated with magnesium sulfate. The aim of our observational study was to compare platelet counts in patients showing EDTA-induced aggregation indicated by aggregation flags and consecutive PTCP, as counted in EDTA- and magnesium sulfate-anticoagulated samples.

Furthermore, citrate anticoagulated samples were examined for aggregation in one of the participating laboratories.

Patients and methods

This study was performed in three routine haematology laboratories (Rostock, Ulm, Dresden, Germany) after approval by the institutional review board of the University of Rostock.

EDTA-anticoagulated whole blood samples for routine haematological analysis were selected for this study when flagged as suspicious for platelet aggregates (even in the case of platelet counts still appearing to be within the normal range). If platelet aggregates were confirmed by microscopic examination of blood smears, the patient was asked for written consent to obtain additional blood samples using collecting tubes anticoagulated with EDTA or magnesium sulfate or, in some cases, sodium citrate samples measured in parallel.

At the beginning of the study, sampling tubes anticoagulated with magnesium sulfate (final concentration 33·8 μmol MgSO4) were provided by the manufacturer (Sarstedt, Nürmbrecht, Germany). Later during the study period these tubes became commercially available (Thromboexact™ Monovette, Sarstedt, Nürmbrecht, Germany).

Platelets were counted by automated routine haematological analysers: two of the participating laboratories used a Coulter LH 750 system (Beckman Coulter, Krefeld, Germany) and one laboratory was equipped with a Sysmex XE 5000 system (Sysmex, Norderstedt, Germany). Blood smears were prepared and May-Grünwald/Giemsa stained according to standard operating procedures (Pappenheim, 1908). Peripheral blood films were analysed and documented by computer-assisted microscopic differentiation (Diffmaster™, Sysmex). One of the participating laboratories modified the protocol by analysing platelet counts in citrate-anticoagulated blood samples (n = 10) after mathematical correction for dilution by the anticoagulant.

To demonstrate the anti-aggregating effect of the magnesium-based anticoagulation, platelet aggregation studies were performed in blood samples from healthy donors collected by the Thromboexact™ (TE) and the standard hirudin-containing tube (S-Monovette™ Hirudin, Sarstedt, Nürmbrecht, Germany). Aggregation studies were performed using a Multiplate™ analyser (Dynabyte Medical, Munich, Germany). Aggregation was induced by adenosine diphosphate (ADP test) or by arachidonic acid (ASPI test) and is expressed as area under the curve (AUC). The normal aggregation elicited by ADP ranges from 53 to 122 units (u), and for ASPI from 75 to 136 u, respectively. The analyser and the procedures were previously described in detail (Toth et al, 2006).

Statistical analysis

SPSS version 16·0 (IBM, NY, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics [including mean, standard deviation (SD) and standard error of mean (SEM)] were calculated to characterize the study population. The normal distribution of the complete blood count (CBC) parameters was checked using the Kolmogorow–Smirnow test. All comparisons for statistical significance between two anticoagulants were performed using the paired t test. Statistical significance was achieved if P < 0·05.

Results

In three different University-based haematology laboratories a total of 44 patients (26 females and 18 males) aged between 18 to 72 years, were included in this study. Clinical diagnoses included coronary heart disease (n = 12), acute upper respiratory tract infections (n = 5), diabetes mellitus or acute trauma or postoperative care (n = 17). No specific diagnoses were obtained for the remaining patients. The criteria for selecting PTCP patients were unexpectedly low platelet counts and/or positive flagging for platelet aggregates.

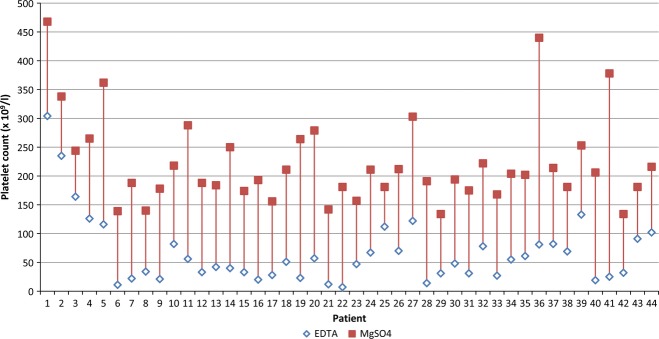

Platelet counts in samples flagged for ‘platelet aggregates’ although anticoagulated with EDTA ranged from 7 × 109/l to 304 × 109/l whereas in magnesium-anticoagulated samples from the same individuals the platelet counts ranged from 134 × 109/l to 468 × 109/l (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Platelet counts in 44 patients with EDTA-induced PTCP (open rhombus) corrected by parallel measurement in magnesium-anticoagulated blood samples (filled squares). The difference is statistically significant (paired t-test). In three individuals the analyser flagged the platelet count for aggregation although the values appeared to be in the normal range. This is due to the fact that PTCP is time-dependent and platelets were measured relatively early after blood sampling.

The mean platelet count in EDTA-anticoagulated blood of individuals with PTCP was 66 × 109/l whereas the mean platelet count in magnesium-anticoagulated tubes was 223 × 109/l. The mean absolute increase of platelets in samples anticoagulated with magnesium sulphate was 154 × 109/l (+230%) ranging from 69 × 109/l (+162%) to 285 × 109/l (+475%). In one individual, the initial platelet count was 7 × 109/l in the presence of EDTA; this increased to 181 × 109/l when measured in parallel using TE.

The study protocol did not schedule the use of citrated blood samples in parallel; nevertheless in 10 patients such data were available (see Table I). In four patients the platelet count was comparable to those obtained in MgSO4; five out of six patients showing lower platelet counts in citrate samples were flagged for aggregates. The count differences to the results achieved with magnesium anticoagulant samples ranged between 92 and 181 × 109/l.

Table I.

Platelet counts in blood samples from 10 individuals with pseudothrombocytopenia anticoagulated with ethylenediamine-tetra acetic acid (EDTA), citrate or MgSO4

| Platelet count (×109/I) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | EDTA | Citrate | MgSO4 |

| 4 | 126* | 266 | 265 |

| 5 | 57* | 172* | 279 |

| 20 | 25* | 313 | 378 |

| 21 | 116* | 356 | 362 |

| 23 | 78* | 213 | 222 |

| 30 | 12* | 20* | 142 |

| 32 | 81* | 269* | 440 |

| 36 | 48 | 102 | 194 |

| 41 | 47* | 66* | 157 |

| 44 | 102 | 222 | 216 |

The samples flagged by the Sysmex haematology analyser are identified by an asterisk.

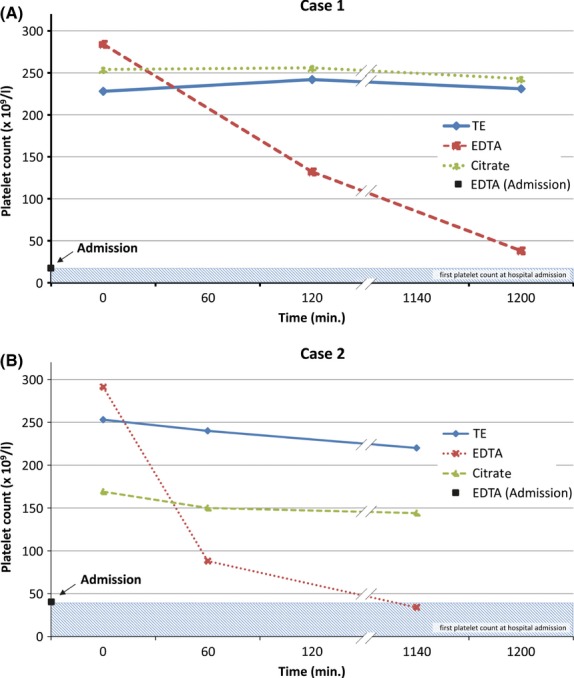

In two patients we documented the influence of time and anticoagulant on the phenomenon of PCTP in more detail. On receipt of the EDTA-anticoagulated samples in the laboratory, platelet counts were low (17 × 109/l and 35 × 109/l). Thrombocytopenia, unexpected for clinical reasons but suggested by platelet aggregate flag, led us ask the patient to consent for additional sampling of blood anticoagulated with EDTA, citrate, and magnesium sulfate, respectively. The platelet counts were immediately performed in all samples, yielding numbers within the reference interval of 284/291 × 109/l (EDTA), 254/169 × 109/l (citrate), and 228/253 × 109/l (TE). With progressively elapsing time between blood collection and platelet enumeration, platelet counts decreased dramatically in the EDTA sample, in contrast to the samples anticoagulated with citrate or magnesium (Fig 2A). In the second patient the platelet count at admission was also low, platelet counts in consecutively collected new samples (anticoagulated by EDTA, citrate und magnesium sulphate) are depicted in Fig 2B. After one and two hours of storage at room temperature the platelet counts decreased continuously in the EDTA samples of both patients. Platelet counts also decreased in the citrate sample from one patient. The number of platelets in the TE sample remained stable for up to 20 h (Fig 2A, B).

Fig 2.

Time-dependent progression of anticoagulant-induced pseudothrombocytopenia (PTCP). Both cases were documented independently from the primary study. The black square and the hatched area indicate the first platelet count performed in an EDTA-anticoagulated blood sample drawn at admission and measured after arrival of the sample at the routine haematological laboratory. The red line (cross symbols) represents the time-dependent decrease of platelets in the EDTA-anticoagulated sample; the green line indicates platelet counts in citrate anticoagulated blood and the blue line (rhombus symbol) demonstrates platelet counts in magnesium-anticoagulated blood. EDTA, ethylenediamine-tetra acetic acid; TE, Thromboexact™.

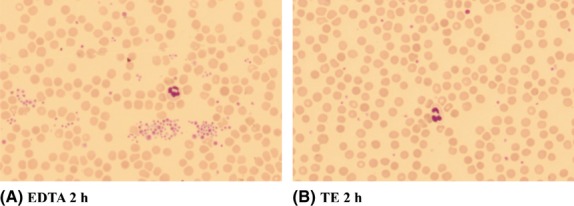

Platelet aggregation as a function of time in EDTA samples was documented in stained blood smears (Fig 3). In contrast, platelet aggregation could not be detected in magnesium-anticoagulated samples.

Fig 3.

Platelet aggregation in a blood smear from a patient with EDTA-induced pseudothrombocytopenia (left) as compared to a smear prepared from magnesium-anticoagulated blood from the same patient (right). EDTA, ethylenediamine-tetra acetic acid; TE, Thromboexact™.

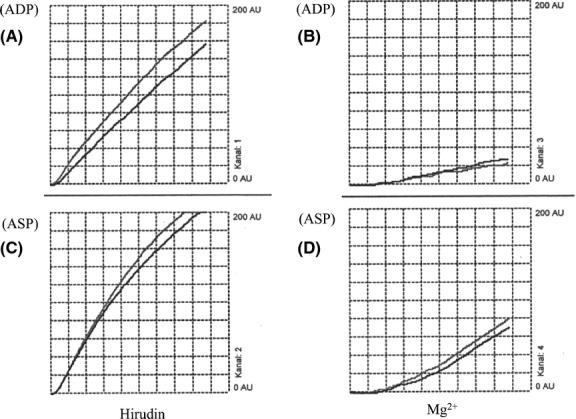

We further compared platelet aggregation in healthy volunteers using the Multiplate™ analyser. Aggregation induced by ADP or arachidonic acid was effectively inhibited when platelets were collected in TE (example shown in Fig 4). The AUC values (u) as a measure of aggregation were suppressed by approximately 88% and 77% when compared to platelets collected in hirudin-anticoagulated tubes. This suppression of platelet aggregation was confirmed in three further experiments with similar results (data not shown).

Fig 4.

MultiplateR platelet function analysis. Platelet aggregation induced by adenosine diphosphate (ADP) (A, B) or arachidonic acid (ASP) (C, D) in whole blood samples from a healthy donor with normal platelet count (320 × 109/l). Blood was drawn into collection tubes containing hirudin (A, C) or magnesium (B, D). The areas under the curve (AUC) are expressed by arbitrary units (u). The ADP-induced aggregation (hirudin tubes) gave an AUC of 81 u (53–122 u), the ASP-induced aggregation gave an AUC of 110 u (75–136 u). The corresponding results in blood samples collected into Thromboexact™ tubes were 10 u and 25 u, respectively.

To prove that magnesium-anticoagulated blood samples can also be used for the determination of other routine haematological parameters we compared the automated WBC count and differentiation as well as the quality of blood smears for microscopic WBC differentiation in EDTA- and magnesium-anticoagulated samples (Table I and III). We compared erythrocytes, leucocytes and differential counts in EDTA- and magnesium-anticoagulated samples (Table II and III). Erythrocytes, leucocytes and differential counts were comparable. The statistical comparison showed no significant difference between both anticoagulants, although the number of platelets was slightly lower in magnesium-anticoagulated blood.

Table III.

Comparison of absolute complete blood count (CBC) in blood samples from pseudothrombocytopenic (PTCP) individuals anticoagulated either with ethylenediamine-tetra acetic acid (EDTA) or MgSO4 collected at the same time. The CBC were similar except for platelet counts, due to EDTA-induced PTCP, which were corrected by MgSO4

| Erythrocytes | Leucocytes | Platelets | Neutrophils | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | EDTA | MgSO4 | EDTA | MgSO4 | EDTA | MgSO4 | EDTA | MgSO4 |

| 23 | 4·63 | 4·38 | 17·16 | 14·23 | 102 | 209 | 13·31 | 11·41 |

| 30 | 4·93 | 4·99 | 10·05 | 10·24 | 47 | 157 | 5·66 | 5·60 |

| 44 | 4·81 | 4·81 | 5·74 | 5·86 | 48 | 194 | 4·09 | 4·21 |

| Patient | Lymphocytes | Monocytes | Eosinophils | Basophils | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EDTA | MgSO4 | EDTA | MgSO4 | EDTA | MgSO4 | EDTA | MgSO4 | |

| 23 | 2·21 | 1·72 | 1·62 | 1·09 | 0·00 | 0·00 | 0·02 | 0·01 |

| 30 | 3·14 | 3·37 | 1·00 | 1·02 | 0·22 | 0·21 | 0·03 | 0·04 |

| 44 | 1·19 | 1·18 | 0·39 | 0·4 | 0·05 | 0·05 | 0·02 | 0·02 |

Table II.

Comparison of absolute complete blood count (CBC) in blood samples from non-pseudothrombocytopenic individuals anticoagulated either with ethylenediamine-tetra acetic acid (EDTA) or MgSO4. Statistical analysis showed no significant difference in CBC between both anticoagulants, although the number of platelets is slightly lower in MgSO4 anticoagulated blood. The compared cell counts are strongly correlated as expressed by correlation coefficient >0·9

| Erythrocytes | Leucocytes | Platelets | Neutrophils | Lymphocytes | Monocytes | Eosinophils | Basophils | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | EDTA | MgSO4 | EDTA | MgSO4 | EDTA | MgSO4 | EDTA | MgSO4 | EDTA | MgSO4 | EDTA | MgSO4 | EDTA | MgSO4 | EDTA | MgSO4 |

| N1 | 3·07 | 3·04 | 3·11 | 3·03 | 198·00 | 152·00 | 1·77 | 1·69 | 1·03 | 1·06 | 0·22 | 0·17 | 0·08 | 0·09 | 0·01 | 0·02 |

| N2 | 4·05 | 4·06 | 10·01 | 9·82 | 378·00 | 325·00 | 7·41 | 7·42 | 1·72 | 1·58 | 0·52 | 0·48 | 0·35 | 0·33 | 0·01 | 0·02 |

| N3 | 2·94 | 2·97 | 5·07 | 5·02 | 206·00 | 186·00 | 3·48 | 3·44 | 1·08 | 1·10 | 0·40 | 0·37 | 0·08 | 0·10 | 0·03 | 0·03 |

| N4 | 3·44 | 3·45 | 9·29 | 8·63 | 185·00 | 170·00 | 7·52 | 6·96 | 1·00 | 0·96 | 0·50 | 0·48 | 0·25 | 0·19 | 0·02 | 0·06 |

| N5 | 4·30 | 4·85 | 8·40 | 8·05 | 178·00 | 156·00 | 5·03 | 4·79 | 2·35 | 2·39 | 0·69 | 0·79 | 0·05 | 0·06 | 0·02 | 0·02 |

| N6 | 4·90 | 4·74 | 9·76 | 9·74 | 116·00 | 107·00 | 8·60 | 8·58 | 0·44 | 0·46 | 0·63 | 0·63 | 0·09 | 0·07 | 0·00 | 0·02 |

| N7 | 4·41 | 4·74 | 5·68 | 5·67 | 266·00 | 234·00 | 2·99 | 2·93 | 2·01 | 1·96 | 0·51 | 0·62 | 0·15 | 0·14 | 0·02 | 0·01 |

| N8 | 4·63 | 4·71 | 8·52 | 8·10 | 352·00 | 279·00 | 3·25 | 3·20 | 3·76 | 3·55 | 0·73 | 0·61 | 0·70 | 0·65 | 0·08 | 0·12 |

| N9 | 4·65 | 4·64 | 5·87 | 5·61 | 181·00 | 155·00 | 3·04 | 2·91 | 1·66 | 1·68 | 0·62 | 0·49 | 0·52 | 0·51 | 0·03 | 0·03 |

| N10 | 3·86 | 4·44 | 6·06 | 5·76 | 181·00 | 168·00 | 3·53 | 3·33 | 1·91 | 1·90 | 0·37 | 0·28 | 0·23 | 0·22 | 0·02 | 0·02 |

| N11 | 4·29 | 4·42 | 8·35 | 7·58 | 299·00 | 223·00 | 5·37 | 5·00 | 1·35 | 1·04 | 1·14 | 1·18 | 0·45 | 0·32 | 0·45 | 0·04 |

| N12 | 3·98 | 4·39 | 5·12 | 4·77 | 405·00 | 322·00 | 3·61 | 3·40 | 0·90 | 0·83 | 0·52 | 0·44 | 0·07 | 0·07 | 0·02 | 0·03 |

| N13 | 4·42 | 4·34 | 18·74 | 17·58 | 306·00 | 262·00 | 14·38 | 13·68 | 1·90 | 0·68 | 2·33 | 2·11 | 0·12 | 0·09 | 0·01 | 0·02 |

| N14 | 3·03 | 3·90 | 12·97 | 12·50 | 378·00 | 326·00 | 10·22 | 9·85 | 1·29 | 1·38 | 1·29 | 1·10 | 0·15 | 0·14 | 0·02 | 0·03 |

| N15 | 2·69 | 3·86 | 10·57 | 10·48 | 389·00 | 355·00 | 8·00 | 8·00 | 1·75 | 1·63 | 0·41 | 0·46 | 0·31 | 0·30 | 0·10 | 0·08 |

| N16 | 3·84 | 3·84 | 11·98 | 11·57 | 225·00 | 205·00 | 9·74 | 9·42 | 1·17 | 1·06 | 0·78 | 0·79 | 0·28 | 0·28 | 0·01 | 0·03 |

| N17 | 5·07 | 5·05 | 8·59 | 8·77 | 215·00 | 186·00 | 5·74 | 5·74 | 1·70 | 1·91 | 0·78 | 0·70 | 0·32 | 0·37 | 0·04 | 0·05 |

| N18 | 5·22 | 5·26 | 7·66 | 7·85 | 195·00 | 177·00 | 5·61 | 5·71 | 1·55 | 1·57 | 0·42 | 0·50 | 0·07 | 0·06 | 0·01 | 0·01 |

| N19 | 5·05 | 5·00 | 5·12 | 5·11 | 175·00 | 150·00 | 2·54 | 2·45 | 2·05 | 2·11 | 0·40 | 0·42 | 0·10 | 0·11 | 0·03 | 0·02 |

| N20 | 5·01 | 5·06 | 5·69 | 5·21 | 299·00 | 258·00 | 2·51 | 2·46 | 2·58 | 2·27 | 0·47 | 0·38 | 0·10 | 0·07 | 0·03 | 0·03 |

| N21 | 5·17 | 5·17 | 6·66 | 6·88 | 271·00 | 226·00 | 3·43 | 3·51 | 2·34 | 2·34 | 0·60 | 0·69 | 0·26 | 0·31 | 0·03 | 0·03 |

| Mean | 4·19 | 4·38 | 8·25 | 7·99 | 257·05 | 220·10 | 5·61 | 5·45 | 1·69 | 1·59 | 0·68 | 0·65 | 0·23 | 0·21 | 0·05 | 0·03 |

| SEM | 0·17 | 0·15 | 0·76 | 0·72 | 18·65 | 15·28 | 0·70 | 0·68 | 0·16 | 0·16 | 0·10 | 0·09 | 0·04 | 0·04 | 0·02 | 0·01 |

| r | 0·90 | 0·99 | 0·98 | 0·99 | 0·92 | 0·98 | 0·98 | 0·25 | ||||||||

SEM, standard error of the mean.

The quality of blood smears prepared from EDTA- and magnesium-anticoagulated blood samples was comparable and the results of microscopic WBC differentiation, documented by computer-assisted microscopy, showed no significant deviations (data not shown).

Discussion

The present study aimed to demonstrate that the platelet-inhibiting potential of magnesium sulfate can effectively prevent platelet aggregation in whole blood samples from patients showing PTCP in the presence of EDTA.

Platelets are not fully stabilized in EDTA-anticoagulated blood samples. They undergo changes in shape and size and finally acquire a more spheroid form than their native discoid shape, thus leading to time-dependent changes of the mean platelet volume (MPV) (McShine et al, 1990; Banfi et al, 2007). This is probably the main reason for the conflicting database concerning the diagnostic value of MPV analysis (Thompson et al, 1983; Martin & Trowbridge, 1990). Therefore, alternative anticoagulants were repeatedly proposed to be used for MPV analysis, including adenosine/citrate/dextrose and sodium EDTA (Thompson et al, 1983), sodium citrate and prostaglandin E1 (Trowbridge et al, 1985), citrate/theophyllin/adenosine/dextrose and pyridoxal phosphate (Lippi et al, 1990; Ohnuma et al, 1988).

Recently it has been proposed that EDTA-induced platelet clumps can be dissociated by a mixture of calcium chloride for re-association of glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIIa complex and sodium heparin for maintaining anticoagulation to correctly estimate platelet counts (Chae et al, 2012). The addition of an aminoglycoside antibiotic (e.g. kanamycin) has similarly been used to count platelets in cases of PTCP (Sakurai et al, 1997; Hae et al, 2002). The mechanism of this effect is not clear but it might be explained by sodium-citrate, which is an additive for stabilizing the drug preparation.

What all these anticoagulant cocktails have in common is that they are unstable and that their individual preparation is expensive. For MPV analysis, citrate anticoagulation as used for RBC sedimentatio seems more practicable and reliable compared to EDTA (von Stein, 2004). However, cell counts need to be corrected due to the dilution effect of added citrate solution. Practicability, stability and cost issues continue to call for alternative new anticoagulants for platelet analysis.

In individuals without EDTA-induced PTCP the platelet counts were regularly lower in samples anti-coagulated with magnesium-sulfate. This phenomenon is obviously due to the fact that the MPV is higher in EDTA anti-coagulated blood (10·6 fl) as compared to magnesium anti-coagulated blood (9·6 fl). The time-dependent swelling of cells in EDTA samples is known from the literature (McShine et al, 1990; Macey et al, 2002).

Automated haematological analysers are calibrated with EDTA samples; this might explain that the lower MPV of platelets in magnesium samples leads to the loss of platelets with an MPV lower than the values set as ‘lower gate’ for platelet counting.

The phenomenon of PTCP is usually observed in the presence of EDTA as anticoagulant (Mant et al, 1975). It is known from the literature that alternative anticoagulants, such as citrate or heparin, may also lead to in vitro platelet aggregation (McShine et al, 1990; Schrezenmeier et al, 1995). In the present study we also documented PTCP in samples anticoagulated by citrate and in one case also in the presence of heparin (data not shown). Although rare, the observation of spontaneous aggregation in the presence of different anticoagulants raises the question of whether this might be related to different underlying mechanisms of action. Schrezenmeier et al (1995) proposed that the phenomenon of in vitro platelet aggregation should be collectively called ‘anticoagulant-induced PTCP’.

The underlying mechanism of the time-dependant aggregate formation is at present unknown. It has been postulated that cold-reactive anti-platelet antibodies, mainly of the IgG class, are directed against a hidden epitope of the platelet GPIIa/GPIII receptor complex. This epitope becomes accessible because of conformational changes of the receptor due to the calcium complexing effect of EDTA (Fitzgerald & Phillips, 1985).

There are only a few reliable data on the incidence of EDTA-induced PTCP. The overall prevalence is estimated to be approximately 0·10%, with numbers being slightly higher in ill or hospitalized patients as compared to outpatients (Payne & Pierre, 1984; Vicari et al, 1988; Silvestri et al, 1995; Bartels et al, 1997). In highly selected patients with thrombocytopenia of unknown origin, the prevalence increases to between 1·25% and 15% (Manthorpe et al, 1981; Silvestri et al, 1995). Females seem to have a slightly higher incidence than males (ratio 3:2) as reported earlier (Püllen & Briehl, 1994). The occurrence of PTCP is not associated with any specific disease entity and has been described in healthy persons (Sweeney et al, 1995). Therefore, it was referred to as a ‘laboratory disease’ (Gschwandtner et al, 1997).

If PTCP is suspected in the haematology laboratory because of an analyser flag and/or for clinical issues (unexpected low platelet count not matching clinical presentation), a peripheral blood smear easily documents platelet aggregates to confirm the diagnosis. A new blood sample, anticoagulated with citrate is usually collected and rapidly transported to the laboratory for automated platelet counting without delay. Results need to be corrected for the citrate-based dilution effect. Nevertheless, in 15–20% of EDTA-induced PTCP platelets may also aggregate in the presence of citrate (Bizarro, 1995), rendering this approach limited for practical reasons.

Before EDTA was introduced as the anticoagulant of choice for haematology testing, magnesium salts were used as anticoagulants for sampling capillary blood for platelet enumeration (Lenhartz & Meyer, 1934). Later, magnesium was used as systemic anticoagulant in patients suffering from coronary heart disease (Gries et al, 1999; Shecter et al, 1999). Although this aggregation-inhibiting effect has been known for decades, the true underlying mechanisms remain unknown.

Magnesium has been labelled ‘nature’s calcium antagonist’ due to its ability to reduce the thrombin-stimulated calcium influx into platelets, which is one of the initial steps of platelet aggregation. In vitro it was also shown that the release of ß-thromboglobulin and thromboxane B2 from platelets is reduced with increasing magnesium concentrations (Hwang et al, 1992). Furthermore, magnesium may induce membrane fluidity changes, thus interfering with fibrinogen binding to the GPIIb/IIIa complex. By this action magnesium triggers the formation of AMP, ultimately resulting in inhibition of P 47 phosphorylation and intracellular calcium mobilization (Sheu et al, 2002). Our investigations on platelet aggregability (Fig 4) confirm the observation that magnesium inhibits platelet aggregation stimulated either by strong (collagen, thrombin; data not shown) or by weak agonists (ADP, arachidonic acid). Therefore it is surprizing that magnesium never became a candidate blood anticoagulant to be used for blood cell counting.

There are very few publications dealing with the usefulness of magnesium as anticoagulant in the laboratory (Kondo et al, 2002). The only publication on its effect in pseudothrombocytopenia was published in Japanese and probably reached only a smaller section of the scientific community (Nakamoto et al, 1986). Using an automated blood cell analyser (Sysmex SE 2100), the authors investigated the time-dependent effect of magnesium- and EDTA-anticoagulation on blood cell enumeration and automated WBC differentiation in patients with PTCP. They reported that magnesium sulfate normalized the platelet counts without interfering with other blood cell counts or differentiation results. These data find full confirmation in our present investigation.

If cases of PTCP are not being identified in the laboratory and/or for clinical reasons, the falsely low platelet count may trigger unnecessary, expensive and even invasive diagnostic or therapeutic procedures (Nilsson & Norberg, 1986; Yamada et al, 2008). To avoid this and to enable a safe and practical alternative, we recommend the use of magnesium sulphate anticoagulated blood samples for platelet counting if blood counts from EDTA samples do not match clinical expectations and/or are being flagged as suggestive of platelet aggregates by the automated haematology analyser.

Conflict of interest

The authors PSW and MS were supported in part by a research grant from Sarstedt (Nürmbrecht, Germany). PSW received lecture honoraria by B. Braun-Melsungen (Melsungen, Germany), Roche (Mannheim, Germany), Beckmann-Coulter (Krefeld, Germany) and Sarstedt (Nürmbrecht, Germany).

References

- Banfi G, Salvagno GL, Lippi G. The role of ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) as in vitro anticoagulant for diagnostic purposes. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine: CCLM/FESCC. 2007;45:565–576. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2007.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels PC, Schoorl M, Lombarts AJ. Screening for EDTA-dependent deviations in platelet counts and abnormalities in platelet distribution histograms in pseudothrombocytopenia. Scandinavian Journal of Clinical and Laboratory Investigation. 1997;57:629–636. doi: 10.3109/00365519709055287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizarro N. EDTA-dependent pseudothrombocytopenia: a clinical and epidemiological study of 112 cases with 10-year follow up. American Journal of Hematology. 1995;50:103–109. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830500206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae H, Kim M, Lim J, Oh EJ, Kim Y, Han K. Novel method to dissociate platelet clumps in EDTA-dependent pseudothrombocytopenia based on the pathophysiological mechanism. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine : CCLM/FESCC. 2012;50:1387–1391. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2011-0892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald LA, Phillips DR. Calcium regulation of the platelet membrane glycoprotein IIb-IIIa complex. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1985;260:11366–11374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowland E, Kay HE, Spillman JC, Williamson JR. Agglutination of platelets by a serum factor in the presence of EDTA. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1969;22:460–464. doi: 10.1136/jcp.22.4.460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gries A, Bode C, Gross S, Peter K, Böhrer H, Martin E. The effect of intravenously administered magnesium on platelet function in patients after cardiac surgery. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 1999;88:1213–1219. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199906000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gschwandtner ME, Siostrzonek P, Bodinger C, Neunteufl T, Zauner C, Heinz G, Maurer G, Panzer S. Documented sudden onset of pseudothrombocytopenia. Annals of Hematology. 1997;74:283–285. doi: 10.1007/s002770050301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hae LA, Young IJ, Young SC, Jung YL, Hae WL, Seong RK, Joon S, Weon L, Chun JJ. EDTA-dependent pseudothrombocytopenia confirmed by supplementation of kanamycin. A case report. The Korean Journal of Internal Medicine. 2002;17:65–68. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2002.17.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang DL, Yen CF, Nadler JL. Effect of extracellular magnesium on platelet activation and intracellular calcium mobilization. American Journal of Hypertension. 1992;5:700–706. doi: 10.1093/ajh/5.10.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Council for Standardization in Haematology. Recommendations of the International Council for Standardization in Haematology for ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid anticoagulation of blood cell counting and sizing: expert panel on cytometry. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1993;100:371–372. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/100.4.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo H, Kobayashi E, Itani T, Tatsumi N, Tsuda I. Hematology tests of blood anticoagulated with magnesium sulphate. The Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health. 2002;33(Suppl. 2):6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhartz H, Meyer E. Mikroskopie und Chemie am Krankenbett. Berlin: Springer; 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Lippi G, Plebani M. EDTA-dependent pseudothrombocytopenia: further insights and recommendations for prevention of a clinically threatening artefact. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine : CCLM/FESCC. 2012;50:1281–1285. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2012-0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippi U, Schinella M, Nicoli M, Modena N, Lippi G. EDTA-induced platelet aggregation can be avoided by a new anticoagulant also suitable for automated complete blood count. Haematologica. 1990;75:38–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macey M, Azam U, McCarthy D, Webb L, Chapman ES, Okrongly D, Zelmanovic D, Newland A. Evaluation of the anticoagulants EDTA und citrate, theophylline, adenosine, and dipyridamole (CTAD) for Assessing platelet activation on the ADVIA 120 hematology system. Clinical Chemistry. 2002;48(6 Pt 1):891–899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mant MJ, Doery JC, Gauldie J, Sims H. Pseudothrombocytopenia due to platelet aggregation and degranulation in blood collected in EDTA. Scandinavian Journal of Haematology. 1975;15:161–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1975.tb01070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manthorpe R, Kofod B, Wiik A, Saxtrup O, Svehag SE. Pseudothrombocytopenia. In vitro studies on the underlying mechanism. Scandinavian Journal of Haematology. 1981;26:385–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J, Trowbridge A. Platelet Heterogeneity: Biology and Pathology. London: Springer; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- McShine RL, Sibinga S, Brozovic B. Differences between the effects of EDTA and citrate anticoagulants on platelet count and mean platelet volume. Clinical and Laboratory Haematology. 1990;12:277–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2257.1990.tb00038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamoto K, Sugibayashi S, Takahashi A, Terauchi S, Hada A, Munakata M, Teraoka A, Komiyama Y, Egawa H, Murata K. Platelet count in EDTA-dependent pseudothrombocytopenia: application of MgSO4 as an anticoagulant. Rinsho byori. The Japanese Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1986;34:167–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson T, Norberg B. Thrombocytopenia and pseudothrombocytopenia: a clinical and laboratory problem. Scandinavian Journal of Haematology. 1986;37:341–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1986.tb02324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnuma O, Shirata Y, Miyazawa K. Use of theophylline in the investigation of pseudothrombocytopenia induced by edetic acid (EDTA-2K) Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1988;41:915–917. doi: 10.1136/jcp.41.8.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappenheim A. Panoptische Universalfärbung für Blutpräparate. Medizinische Klinik. 1908;32:1244–1245. [Google Scholar]

- Payne BA, Pierre RV. Pseudothrombocytopenie: a laboratory artefact with potentially serious consequences. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 1984;59:123–125. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)60247-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proesche F. Anticoagulant properties of ethylene bisimmodiacetic acid (ethylenediamine-tetraacetic acid) Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. 1951;76:619. [Google Scholar]

- Püllen R, Briehl E. Pseudothrombocytopenia. Etiology, incidence and significance of a laboratory artefact. Medizinische Klinik. 1994;89:196–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson N, Mangin P, Saugy M. Time and temperature dependent changes in red blood cell analytes used for testing erythropoietin abuse in sports. Clinical Laboratory. 2004;50:317–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai S, Shiojima I, Tanigawa T, Nakahara K. Aminogylcosides prevent and dissociate the aggregation of platelets in patients with EDTA-dependent pseudothrombocytopenia. British Journal of Haematology. 1997;99:817–823. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.4773280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrezenmeier H, Müller H, Gunsilius E, Heimpel H, Seifried E. Anticoagulant-induced pseudothrombocytopenia and pseudoleucocytosis. Thromb Haemostasis. 1995;73:506–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shecter M, Merz CN, Paul-Labrador M, Meisel SR, Rude RK, Molloy MD, Dwyer JH, Shah PK, Kaul S. Oral magnesium supplementation inhibits platelet dependent thrombosis in in patients with coronary artery disease. American Journal of Cardiology. 1999;84:152–156. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00225-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheu JR, Hsiao G, Shen MY, Fong TH, Chen YW, Lin CH, Chou DS. Mechanisms involved in the antiplatelet activity of magnesium in human platelets. British Journal of Haematology. 2002;119:1033–1041. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shreiner DP, Bell WR. Pseudothrombocytopenia: manifestation of a new type of platelet agglutinin. Blood. 1973;42:541–549. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-08-736009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvestri F, Virgolini L, Savignano C, Zaja F, Velisig M, Baccarani M. Incidence and diagnosis of EDTA-dependent pseudothrombocytopenie in a consecutive outpatient population referred for isolated thrombocytopenia. Vox Sanguinis. 1995;68:35–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1995.tb02542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solanki DL, Blackburn BC. Spurious leukocytosis and thrombocytopenia. A dual phenomenon caused by clumping of platelets in vitro. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1983;250:2514–2515. doi: 10.1001/jama.250.18.2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Stein S. 2004. Untersuchungen zum mittleren Thrombozytenvolumen - Methodik und klinische Anwendung am Beispiel der Thrombozytose [Thesis]. Medical Faculty of the University of Rostock.

- Sweeney JD, Holme S, Heaton WA, Campbell D, Bowen ML. Pseudothrombocytopenia in plateletpheresis donors. Transfusion. 1995;35:46–49. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1995.35195090660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson CB, Diaz DD, Quinn PG, Lapins M, Kurtz SR, Valeri CR. The role of anticoagulation in the measurement of platelet volumes. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1983;80:327–332. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/80.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth O, Calatzis A, Pens S, Losonczy H, Siess W. Multiplate electrode aggregometry: a new device to measure platelet aggregation in whole blood. Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2006;96:781–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trowbridge EA, Reardon DM, Hutchinson D, Pickering C. The routine measurement of platelet volume: a comparison of light scattering and aperture-impedance technologies. Clinical Physics and Physiological Measurement. 1985;6:221–238. doi: 10.1088/0143-0815/6/3/003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicari A, Banfi G, Bonini PA. EDTA-dependent pseudothrombocytopaenia: a 12-month epidemiological study. Scandinavian Journal of Clinical and Laboratory Investigation. 1988;48:537–542. doi: 10.3109/00365518809085770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada EJ, Souto AF, de Souza Eda E, Nunes CA, Dias CP. Pseudothrombocytopenia in a patient undergoing splenectomy of an accessory spleen. Case report. Revista Brasileira de Anestesiologia. 2008;58:485–488. doi: 10.1590/s0034-70942008000500007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]