Abstract

Eukaryotic chromosomes are condensed into several hierarchical levels of complexity: DNA is wrapped around core histones to form nucleosomes, nucleosomes form a higher-order structure called chromatin, and chromatin is subsequently compartmentalized in part by the combination of multiple specific or unspecific long-range contacts. The conformation of chromatin at these three levels greatly influences DNA metabolism and transcription. One class of chromatin regulatory proteins called insulator factors may organize chromatin both locally, by setting up barriers between heterochromatin and euchromatin, and globally by establishing platforms for long-range interactions. Here, we review recent data revealing a global role of insulator proteins in the regulation of transcription through the formation of clusters of long-range interactions that impact different levels of chromatin organization.

1- Introduction

The proper organization of eukaryotic chromosomes determines the manner in which the DNA sequence is interpreted in a large number of cellular processes, including DNA replication, repair and transcription 1-6. In particular, a gene transcriptional activation state depends on its position in the genome and on its local chromatin structure 7. In addition, three-dimensional loops have been implicated in all levels of chromatin organization ranging from kb-size loops to larger intrachromosomal loops hundreds of kb in size 6, 8, 9. Both kinds of loops were shown to regulate several biological processes, such as X chromosome inactivation 10, and developmentally regulated transcription 11 or repression 12. The connection between transcription regulation and higher-order nuclear organization of chromatin has been a long-standing question in modern biology, and the mechanisms responsible for this connection are just starting to emerge.

Chromatin insulators may be key determinants of the proper organization of eukaryotic chromosomes. These DNA sequences were originally identified in Drosophila melanogaster (hereafter Drosophila) and chicken as distinct cis-regulatory elements that block the action of distant enhancers 13-15 and that might define the boundaries of chromatin domains to demarcate the distinction between heterochromatin and euchromatin16-21. Recent progresses in the field have provided strong support for both types of models, leading to the identification of two major classes of insulators: ‘enhancer blocking’ insulators (EB insulators) block communications between adjacent regulatory elements in a position-dependent manner (e.g. prevent distant enhancers from activating a promoter when placed between them) (Figure 1B), and ‘barrier insulators’ prevent the silencing of euchromatic genes by blocking the spreading to nearby heterochromatin20, 22 (Figure 1A). These insulation activities either trigger the activation or repression of transcription in a locus-dependent manner. The persistence of transcriptionally active genes throughout cell division implies the existence of regulatory elements or epigenetic mechanisms that enforce and maintain the distinction between heterochromatin and euchromatin.

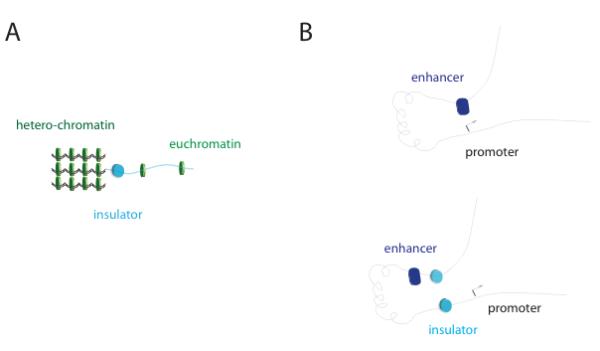

Figure 1. Insulator mechanisms.

A) Barrier insulators (cyan cylinder) physically confine heterochromatin regions (condensed green discs, left) to avoid their spreading to parts of the genome that have to be actively expressed (sparse green discs, right); B) enhancer-blocker insulators (cyan cylinder) positioned between an enhancer (blue) and a promoter (arrow) affect gene expression by avoiding that these two regions get in close contact (left: enhancer contacts promoter, right: insulator prevents enhancer-promoter interactions).

Distinct families of insulators have been described to date, defined by the insulator binding protein (IBP) that is essential for their activity 21, 23. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Saccharomyces pombe, TFIIIC was found to be an evolutionary conserved barrier insulator factor 24-26. Extensive studies in Drosophila have identified five insulator families including those bound by: Suppressor of Hairy-wing [Su(Hw)], boundary element-associated factor (BEAF), Zeste-white 5 (Zw5) 27, the GAGA factor (GAF) 21, and dCTCF28, a distant sequence homologue of mammalian CTCF (see below) . In vertebrates, CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF) is the only insulator protein that has been characterized 29-31, although putative homologues of Drosophila and yeast insulator proteins were also recently identified 32, 33.

Despite this large variety, insulator proteins share common molecular mechanisms. Four general properties have been repetitively associated with the activity of the known insulators and their binding proteins, from yeast to humans:

their activity may be associated to chromatin accessibility, e.g. by interacting or recruiting specific transcription or remodeling factors to position, evict, exchange or modify nucleosomes/histones in their vicinity 20, 34-39 or by preventing DNA methylation 40.

unlike desilencing activities, the activity of insulators more specifically involves directionality and the establishment of long-range interactions with distant elements and/or the clustering of multiple insulators into ‘bodies’ 7, 15, 25, 41-43.

insulator binding proteins might derive from transposons and/or ancient transcription factors, yet it remains unclear if they might function as derivative of promoter elements or promoter decoys/sink 26, 44.

more generally, insulators may be involved in the compartmentalization of the interphasic chromatin, involving interactions with specific nuclear compartments such as lamina or nuclear pore complexes at the nuclear periphery, or other nuclear structures to regulate the activation states of genes through positioning of chromatin 12, 42, 45-47.

Each insulator binding protein interacts with a unique network of partners that is often defined by the chromatin context and genetic location of the insulator element, as well as by the cell cycle stage and cell type. The composition of this network ultimately determines the specific activity of the insulator at that locus. To be able to draw general mechanistic conclusions, it is thus of upmost importance to identify the different factors composing specific insulator elements, to understand the role of these factors, and to characterize their interactions with components of the transcription machinery (e.g. RNA polymerase, transcription factors, enhancers), chromatin remodelers, histone modifiers (e.g. de-/acetylases, de-/methylases) and nuclear architectural proteins (e.g. histones, cohesin, lamina). The use of Chromosome Conformation Capture (3C)48 and derivative technologies 49 is also likely to enable a better understanding of the degrees to which insulators compartmentalize interphasic chromatin with respect to, for instance, chromosome territories 50, as predicted for CTCF 51.

In this review, we will focus on recent data highlighting three different aspects of insulator binding proteins that support their role as key regulators of transcription, local chromatin accessibility as well as long-range interactions.

2. Insulator-binding proteins: the first layer towards insulator formation ?

BEAF was originally identified as an essential factor for the EB activity of the scs’ element 19, the first insulator element reported 18. beaf encodes for two alternative spliced forms: BEAF-32A and 32B. BEAF-32B was shown to be necessary and sufficient for EB activity 23, 52 and to represent the majority (~ 99%) of DNA-bound BEAF 53. BEAF-32 harbors an N-terminal BED finger domain, a C-terminal domain that is involved in protein-protein interactions and self-interaction properties 19, 54, and a middle, coiled-coil region that was suggested to be required to determine its cellular localization 55. As for Su(Hw), or Zw5, there are no sequence homologues of BEAF-32 in vertebrates, although the structural characterization of these proteins and the biochemical analysis of their interaction partners may result in the future identification of potential homologues in vertebrates, as recently suggested for GAF 32. An interesting hypothesis is that the different functional or structural modules in insulator proteins may be encoded in multiple factors in vertebrates. Actually, BED finger domains are found in one or more copies in regulatory factors and transposases from plants, animals and fungi. BED fingers are 50-60 amino acid long, and contain a characteristic motif with two highly conserved aromatic positions and a shared pattern of cysteines and histidines that are predicted to form a zinc finger that belongs to the WRKY–GCM1 zinc-finger superfamily of DNA-binding factors 56. Additional members of this family include transcription factors like ATF2 or DREF 43 as well as numerous human zinc-finger BED proteins of unknown function. Biochemical experiments showed that BEAF-32B (hereafter called BEAF) binds specific DNA sequences mostly as a trimer. Each BEAF subunit targets one CGATA motif, while point mutations within this consensus motif abolish binding and insulation 54. Clusters of 3-4 CGATA motifs create high-affinity (kD ~ 10 pM) binding sites 23 that are often often organized in a pair-wise configuration (‘dual-core’ element) to separate head-to-head gene pairs 35 although additional arrangements were also found 38. Importantly, BEAF binding sites are preferentially distributed in pairs separated by ~10 kb, suggesting that long-range BEAF/BEAF interactions could lead to the formation of long-range DNA contacts. BEAF binding sites partially overlap with dCTCF binding sites 38, 39, suggesting partial redundancies and/or interplay among various EB activities.

Su(Hw) is one of the most extensively studied insulator binding proteins in Drosophila. Su(Hw) possesses EB 57 as well as barrier activity 58, 59 and binds specifically to a sequence motif that was first identified in the gypsy retrotransposon 60. It was earlier suggested that different domains of the protein are involved in either EB or barrier function probably by the recruitment of protein interaction partners 59. Su(Hw) consists of 12 zinc fingers and acidic domains at its N- and C-terminal. In addition, it contains a leucine zipper motif close to the C-terminal end of the protein 61 that is involved in the interaction with Modifier of mdg4 [Mod(mdg4)] 62. A 12bp YRYTGCATAYYY (Y-Pyrimidin, R-Purine) Su(Hw) consensus binding motif was first identified in the gypsy insulator region 60. Further biochemical and genome-wide DNA binding studies of Su(Hw) resulted in hundreds of new non gypsy binding sites from which a 20 bp consensus motif was derived that allows variations in the TGCATA core binding region 63, 64.

Zw5 belongs to the zf-AD (zinc-finger associated domain) superfamily and sequence analysis results in 8 Cys2-His2-type (CH2)-type Zn-fingers (smart.embl-heidelberg.de). Zw5 is awaiting biochemical characterization.

CTCF was originally discovered as a transcription factor regulating c-myc 30. Full length CTCF and dCTCF contain two highly conserved domains: an eleven zinc finger central DNA-binding domain and an N-terminal domain. Recent studies mapping the genome-wide distribution of human CTCF found that it occupies a 11-15 bp core consensus sequence (~ 104 sites, depending on cell type) and binds in vitro to a specific 12 bp variation of this consensus with very high-affinity (KD = 0.1 nM) 65-67. Biochemical assays have indicated that CTCF can in fact use different combinations of the zinc-finger domains to bind different DNA target sequences that may be influenced by post-transcriptional modifications (see below) 68. Mass spectrometry, yeast two-hybrid and biochemical methods showed that CTCF interacts with itself by forming dimers and higher oligomers 69, 70, suggesting a mechanism by which CTCF could mediate long-range interactions. dCTCF was originally discovered as the insulator protein responsible for activity of the Fab-6 and Fab-8 insulator elements in Drosophila 28, 71. An 11 bp consensus sequence was identified as the binding motif of dCTCF and represents a subset of the human CTCF consensus. Full-length dCTCF (818 amino-acids) was shown to bind an instance of this motif (CAGGCGGCGC) in vitro with high-affinity 71.

Finally, GAGA factor (GAF) was first identified as a key regulator of homeotic genes 72 that binds to the DNA consensus motif GA(CT) in the Ultrabithorax promoter 73, later defined as GAGAGAG 74. GAF was shown to possess an N-terminal BTB domain involved in oligomerization and a Cys2-His2-type Zn-finger that is essential for specific DNA binding 75, 76. The C-terminal, glutamine-rich domain of GAF is involved in transcriptional activation 77. Recently, the role of GAF as an IBP has been questioned due to its low EB activity 22, and was rather proposed to function as a ‘de-silencer’ 42 (see below).

Post-transcriptional modifications (e.g. phosphorylation, PAR-ylation and SUMO-ylation) are involved in the regulation of insulator protein activities and will be discussed in Section 6. Such modifications, the chromatin context and the presence of co-factors may in turn regulate or affect the DNA binding patterns of insulator proteins, as suggested by recent genome-wide studies showing that the binding sites occupied by insulator proteins are not solely defined by their consensus sequences.

IBPs are often necessary but not sufficient to ensure insulation activity at a specific locus, and several insulator co-factors have been shown to be additionally required. One example is the gypsy insulator, which in addition to Su(Hw) requires Mod(mdg4)78, 79 and Centrosomal Protein 190 (CP190) 80, a protein originally described for its ability to bind to the centrosome during mitosis81. Recent studies suggest that CP190 plays a crucial role in the insulation function of various IBPs (see below).

3- Genome-wide studies: highlighting the role of insulators in chromatin organization

Genome-wide analysis of the binding of insulator proteins across eukaryotic genomes challenged classic insulator models by unveiling their distribution with respect to multiple annotations, and highlighting their important functions in situ 35, 38, 39, 53, 65, 66, 71, 82, 83. In particular, these binding sites were found to be near the promoters of thousands of active genes and/or at the border of heterochromatin domains, supporting their functions as barrier or EB insulators.

Genome-wide studies in human, mouse and chicken cell types showed that CTCF binds to ~ 30000 binding sites that are located in inter-genic regions (~50 %) and often close to promoters (~20-30 %)65, 66. In Drosophila, genome-wide studies in cultured cells and embryos showed that dCTCF, Su(Hw) and BEAF possess partially redundant localization patterns 35, 38, 39 that strongly correlate with regions of distinct transcriptional activity 38, 39, 53, 65, 71. BEAF and dCTCF binding sites were found to be specifically enriched close to promoters, and to some extent to transcription start sites (TSS) and transcription end sites. The binding profiles of BEAF and dCTCF vary according to distinct cell types, suggesting a role in transcription, cell identity, development and regulation of specific gene ontologies including the cell cycle 35, 38, 53. In contrast, Su(Hw) binding sites were found to be predominantly enriched in or near heterochromatic regions 35, 38, 39, 53, 71. Recently, these distinct genomic distributions were used to define a division of Drosophila IBPs into two major classes depending on the enrichment of their binding sites close to promoters (Class I: BEAF, dCTCF) or in gene-poor regions (Class II: Su(Hw))39. Several BEAF and dCTCF binding sites have since been validated as true EB insulators using classical reporter gene assays 22. However, other studies have also shown that binding sites for BEAF, dCTCF and CTCF are also found to be enriched at the borders of repressed domains 37,82, suggesting that IBPs may function both as barrier and EB insulators, depending on additional co-factors and/or genomic environment. .

Initially, the molecular mechanism of chromatin insulation was tightly linked to chromatin accessibility which is generally coupled to gene activation (for a recent review, see e.g. 84). The first insulator elements were identified based on the sensitivity to DNase I treatment of chromatin at insulator sites, which correspond to hypersensitive sites (HS)16. Chromatin accessibility is not a specific property of insulators, but has been repetitively observed for the characterized insulators and more recently for BEAF, dCTCF and GAF binding sites that mark the most prominent nucleosome-free regions (NFR) genome-wide23, 35, 38, 39, 53, 66, 71. Chromatin opening is essential for desilencing but not sufficient for barrier activity, as suggested using reporter assays in yeast42. Such reporter systems could distinguish desilencing activities (that open chromatin to favor the expression of genes independently of directionality) from the barrier activity of IBPs that depends on long-range interactions with other distant cis-regulatory elements (and thereby of directionality; see section below). The full activity of insulator barriers may thus also depend on their interactions with distant elements, not solely on chromatin accessibility. Recent simulations of chromatin folding may suggest a role of histone depletion (and by extension chromatin remodeling) in facilitating the formation of these chromatin loops 85, arguing for a function of de-silencing activities in regulating long-range interactions.

Experimentally, it was shown that barrier insulators may actually involve interactions with chromatin remodelers20, 34, 66, 82 in order to impede the propagation of repressive marks 34, 36, 86 but also to control de novo deposition of marks in the active region insulated (Figure 2A). The identification of co-factors has been essential to better understand the molecular mechanisms of insulator barriers 31 (see section 6 for a discussion of insulator co-factors). In yeast, the Remodel the Structure of Chromatin (RSC) complex was shown to play a key role in the insulation activity of TFIIIC 36. In Drosophila, it is interesting that dCTCF, BEAF, Su(Hw) and GAF all bind to putative insulator sites that are also bound by CP19038, an essential factor involved in nuclear organization and in restricting the spreading of the heterochromatin histone mark K27me337. In vertebrates, the remodeling activity at the HS4 insulator of the chicken beta-globin locus could be distinguished from the EB insulating activity of CTCF. In this case, barrier activity actually depends on USF (Upstream Stimulatory Factor), a factor that binds to a distinct region of HS4 to mediate the deposition of active histone modifications40, highlighting that barrier and EB functions could be uncoupled. In addition, HS4 also harbors a third region that is recognized by VEZF1 (Vascular Endothelial Zinc Finger 1)87) which independently mediates protection from DNA methylation. Insulator barriers in vertebrates were thus proposed to play a role both in restricting DNA methylation and in recruiting histone modifiers, with functions being required to regulate the establishment of an epigenetically stable silent chromatin state40. Long-range communication among distant insulators may also be more efficient if the intervening sequences are ‘silenced’ as shown for the yeast HMR locus86. The genomic context of insulators may thus be important to consider for insulating activities as the final impact of an insulator will depend on the multiple interactions among other distant elements 44.

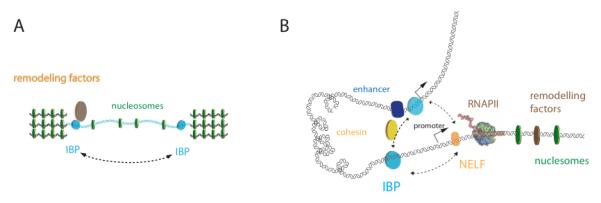

Figure 2. Enhancer-blocking activity and long-range interactions.

(A) The barrier activity of insulators depend on local chromatin structure (nucleosomes, green disks) and on interactions of IBPs with chromatin remodeling factors (brown disk). (B) The enhancer blocking activity may depend on long-range interactions between insulators, mediated by insulator binding proteins (IBP, cyan cylinders). Alternatively, long-range interactions may occur between insulator sequences and RNAPII complexes (atomic model) that are paused upon NELF (orange circle) recruitment. These interactions may involve co-factors such as i.e. cohesin (yellow circle).

Interestingly, the Levine’s group88 demonstrated that paused RNAPII, stalled downstream of a TSS, possesses enhancer blocking activity that is dependent on NELF, a key player of transcriptional pausing by RNAPII. Additionally, it was suggested that the mechanism behind this EB activity involves interactions between paused RNAPII complexes and IBPs, which will prevent the activation of RNAPII by proximal enhancers88 (Figure 2B). Furthermore, other studies showed that a significant fraction of GAF- and BEAF-associated genes interact with NELF53, 89-91. Taken together, these data suggest that this mechanism may be widespread, and further raise the possibility that IBPs may be directly involved in the process of transcriptional pausing. Recent work has suggested alternative strategies for the local organization of chromatin by transcription through the production of non coding RNAs (ncRNAs), involving the chromatin remodeling and elongation factors spt16 and FACT92. Intergenic ncRNAs might actually provide an interplay in the function of insulators (reviewed in 93) and potential feedback loops between insulator-mediated RNAPII binding and the subsequent re-organization of chromatin should be addressed.

The common IBPs and mechanisms shared between chromatin barriers and EB insulators strongly argue that their activities depend on their interaction with a variety of co-factors including key regulators of chromatin structure and on their genomic contexts (distribution with respect to cis-regulatory elements including enhancers, promoters or repressive elements). It is worth noting that the resolution of Chip-chip and Chip-seq experiments is often of the order of ~100-1000 bp. Thus, the resolution of a given experiment sets an upper limit for the maximum precision with which the relative localization of binding sites of IBPs and those of other factors/cis-regulatory elements can be established. Higher resolution genome-wide, and locus-specific studies will be needed in future to validate and further understand the global roles of IBPs.

4- Long-range interactions

A key feature of insulators is their ability to occasionally or temporarily form clusters. Recently, novel methods including 3C 48 and several variants have allowed for the first time to experimentally test whether insulator activity requires the formation of long-range DNA contacts.

One of the first proofs of the existence of insulator-mediated long-range contacts in Drosophila came from studies on the scs and scs’ insulators. Co-immunoprecipitation studies and 3C experiments showed that scs and scs’, which are bound by Zw5 and BEAF, physically interact with each other at a distance of 15 kb 94. Further characterization of such hetero-typic long-range interactions involving distinct IBPs may provide a better understanding of how insulators may in turn regulate gene expression, as recently shown 44. Such long-range interactions among EB insulators can also lead to the enforcement of gene silencing, as illustrated by the Drosophila chromatin remodeling proteins of the Polycomb group (PcG). PcG proteins bind to polycomb response element (PRE) sequences and later recruit a further protein complex called PRC2 that is responsible for gene silencing of the hox cluster 95. It was recently demonstrated that long-range trans interactions between two PcG-binding regulatory elements do not depend on PRE elements as previously thought but rather on the presence of insulators 96.

In vertebrates, CTCF plays a major role at regulating inter- and intra-chromosomal long-range interactions. Indeed, Hi-C and genome-wide data showed that up to ~35% of the total identified long-range interactions carry CTCF binding sites 51. Notably, CTCF binding sites are present at ~60% of the inter-chromosomal and ~20% of the intra-chromosomal long-range interactions. Several genetic regions involved in insulator-mediated long-range interactions by CTCF were studied in detail.

One of the best characterized regions is the chicken beta-globin locus. Four genetic insulators are found at its 5′-end (5′HS4) whereas only one is found at its 3′-end (3′HS1). The binding of CTCF to 5′HS4 and 3′HS1 and its EB activity were shown to block transcription of the beta-globin locus 26, 97. Recent data have shed light into the factors involved in CTCF-mediated long-range interactions. CTCF purification studies from HeLa cell nuclei resulted in co-purification of many sub-nuclear architectural proteins, with nucleophosmin being one of the main factors 69.

The other region studied in detail for CTCFs EB activity is the imprinting control region (ICR) that is located between the Igf2 (insulin like growth factor) gene and the H19 locus. The ICR consists of four CTCF insulator binding sites whose occupation depends on their methylation state. For the maternal allele it was shown in embryonal tissue that the ICR is not methylated and CTCF binds to it. Thereby CTCF blocks the long range interaction between the Igf2 promoter and its enhancer region, the H19 gene locus is active. On the paternal allele, the ICR is methylated and CTCF binding to the ICR is blocked98. This allows enhancer-promoter communication and Igf2 is expressed, whereas the expression of the H19 region is blocked by the binding of its repressor 26. Down-regulation of CTCF, Chip-chip-analysis and 3C-experiments further showed that the long-range interaction between ICR and the Igf2 promoter depends on CTCF 26, 98. Finally, a modified 3C technique was used to reveal that mouse CTCF is also able to promote inter-chromosomal or trans interactions between the ICR from the Igf2/H19 loci on chromosome 7 and Wsb1/Nf1 on chromosome 11 99. Interestingly, long-range interactions at the ICR were also shown to be affected by non-coding RNAs 100. Further studies will be needed to unveil whether ncRNAs play a more general role at the regulation of long-range contacts among enhancer, promoters and insulators, and whether this regulation feedbacks into the production of such ncRNAs 101.

Studies at several different loci revealed that CTCF interacts with cohesin in the regulation of long-range interactions and the expression of gene clusters. Cohesin is a complex formed by Smc1 and Smc3 heterodimer, the Rad21 (Mcd1, Scc1) kleisin protein family, and Stromalin (SA, Scc3) 102, that was first described for its key role in the structural organization of chromosomes during replication and is essential for sister chromatid cohesion after DNA replication in S-Phase 103. More recently, cohesin was shown to be involved in gene regulation in yeast 24 and Drosophila 104 through the formation of long-range chromatin interactions105 . Genome-wide studies in humans showed that ~71% of CTCF and cohesin binding sites overlap, with CTCF being required for the specific localization pattern of cohesin 106. More detailed 3C studies of the apolipoprotein gene region (APO), which contains three CTCF- and three cohesin-enriched sites that result in the formation of two chromatin loops, showed that knockdown of either CTCF or cohesin leads to a disruption of long-range loops and to significant changes in APO expression 107. Similarly, the depletion of cohesin causes an enhanced Igf2 expression and a decrease in H19 expression levels, suggesting that cohesin is part of the enhancer-blocking activity of CTCF 108. More recently, in situ 3D-FISH experiments at the Igh locus showed CTCF depletion leads to only minimal changes in long-range distances 109, suggesting that CTCF is not the only factor responsible for the general architecture of the locus but is rather required to mediate and stabilize long-range interactions. Taken together, these data show that CTCF is a key factor in the organization of gene clusters through the formation of long-range DNA contacts that are essential for transcription.

5- Microscopy studies of insulator proteins

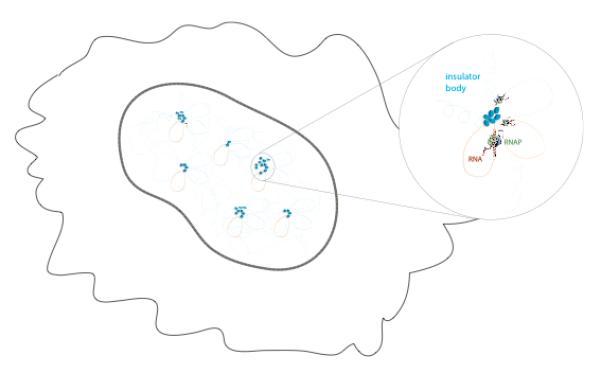

In previous sections, we have shown evidence that: (1) IBPs bind genome-wide to thousands of sites in intergenic and promoter regions, (2) different IBPs may regulate the expression of different gene families, (3) IBPs are necessary for the formation of long-range interactions, and their disruption leads to perturbations in transcription. These observations could be explained by a model in which many insulators cluster together in spatially defined regions of the nucleus. These clusters have been named ‘insulator bodies’ and represent nuclear bodies in which co-regulated genes come together in spatially localized regions through the formation of long-range interactions (Figure 3). Interestingly, insulator bodies may be spatially or functionally related to transcription factories, which have been experimentally defined as protein-rich foci where resources are shared to optimize the process of transcription 3, although no such link has been experimentally proved.

Figure 3. Insulator bodies.

Several insulator bodies are assembled in the nucleus (solid line) of a cell (membrane as thin wiggly line). An insulator body (top right) consists of a clustering of chromatin loops held together through a network of interactions between IPBs and related factors and involve the formation of higher-order long-range interactions and the co-regulation of multiple genes. Different insulator bodies may regulate distinct gene ontologies, and they may thus vary in size (represented in figure by a different number of IBPs).

Fluorescence microscopy provided the first support of the existence of insulator bodies. Images of fluorescently labeled Su(Hw) and dCTCF 41, 43, 110 show that IBPs gather in a small number of fluorescent clusters per cell (~ 20-50). In addition to Su(Hw) and dCTCF, CP190 was also shown to localize into nuclear bodies 111, suggesting that CP190 could be a common regulator of distinct types of insulator clusters (characterized by each insulator protein subclass).

When considered together, the microscopy images reported in literature show a heterogeneous scenario in which insulator bodies greatly differ in size within single cells and number when comparing different individual cells and different cell types. This heterogeneity may actually reflect their functional role. First, different gene families could be regulated at each insulator body, resulting in clusters of different sizes and compositions that are IBP specific. Second, different insulators could regulate specific epigenetic programs in different cell types 112, resulting in cell-type specific distributions of insulator cluster numbers and sizes. This possibility is tempting as it suggests that cells use insulators to maintain certain epigenetic programs throughout cell division and differentiate by regulating the assembly of distinct classes of insulator bodies. Third, insulator bodies need to be dynamic. At short time scales (~ ms to seconds), molecular processes, such as the structural dynamics of chromatin and higher-order contacts, the kinetics of association/dissociation typical of protein-protein and protein-DNA interactions, and most importantly the process of transcription will define time fluctuations in insulator body statistics. In fact, a recent paper by Akbari et al. 111 showed by time-lapse fluorescence microscopy that CP190 insulator bodies are highly dynamic. On a longer time-scale (~hrs), the dynamic stability of insulator body numbers and sizes will be regulated by cellular factors that vary over the cell-cycle and due to external conditions. Intriguingly, CP190 cycles between its inter-phasic binding sites in G1, overlapping with Su(Hw), BEAF-32, GAF and dCTCF binding sites, and its binding to centrosomes in mitosis 113. Similarly, the clustering of TFIIIC sites into bodies in inter-phasic chromatin25 also cycles to bind to centromeres during mitosis 114, involving potentially conserved mechanisms. It remains unclear to what extent the clustering of insulators depends on local remodeling activities, DNA methylation and/or histone modifications that might in turn favor long-range interactions.

Quantitative and higher resolution fluorescence microscopy methods will be needed to gain more information on the role of static and dynamic heterogeneity of insulator clusters and their role in insulator function and transcription regulation, as well as in the identification of factors associated to insulator bodies.

6- Structural components of an insulator

Although the molecular mechanisms involved in the formation of insulator clusters is still not fully understood, it is clear that in addition to IBPs many insulator co-factors will be required to (1) make the physical contacts required for the cohesion of insulators, (2) organize chromatin through higher-order long-range interactions, and (3) anchor insulators to nuclear structures (such as the nuclear envelope).

The insulator proteins themselves are the first candidates for the protein-protein interactions needed for insulator body cohesion35, 38, 115. CTCF, BEAF and Su(Hw) contain zinc-finger binding domains that allow them to bind DNA specifically, as well as other domains (C-terminus for BEAF, N-terminus for CTCF) that have been implicated in their ability to self-oligomerize19. Self-interactions might be important, for instance as shown for BEAF whose ability to ‘cluster’/bind cooperatively to its multiple binding sites is abolished upon deletion of its C-terminal domain. Characterization of the number of IBPs present in insulator bodies may thus be important to better understand their architecture and/or the minimal/maximal number of IBP molecules needed for DNA binding and/or for clustering. Steric hindrance among multiple chromatin-bound IBP, or other mechanisms, could for example limit insulator clustering. It remains to be demonstrated whether IBPs can make loops between multiple (more than two) insulator binding sites. Current technologies, such as 3C/Hi-C, are only able to directly detect bi-partite interactions (two insulator binding sites only). HiC frequencies are often too small and thus predicted 3-way interactions drop into small, insignificant probabilities. Further methods will need to be developed and used to address this important question.

Insulator proteins, however, are not the only factor that could provide the protein-protein contacts necessary to hold insulator-mediated long-range interactions together. Firstly, ChIP37, 38, 43 and microscopy experiments 41, 43, 110 identified CP190 and Mod(mdg4) as additional cofactors possibly contributing to the cohesion of long-range contacts. Not only these proteins co-localize with dCTCF43, 116, Su(Hw)80 and BEAF38 but are essential to the activity of insulators 80, 112, 117. Moreover, these forms of regulation of insulator body assembly can be responsible for changes in the expression pattern or play some important role in development by maintaining specific epigenetic programs that induce cell differentiation 112. It may be important to study the relative distribution of these factors throughout the cell cycle, as CP190 specifically associates with centrosomes at mitosis.

Secondly, cohesin could play a major role in providing the physical contacts required to maintain insulator-mediated long-range interactions. A body of evidence shows that CTCF interacts with cohesin 106, 108, 118, 119. This interaction involves the C-terminal domain of CTCF and the SA2 subunit of cohesin, which is proposed to bridge chromatin regions bound by CTCF and encircled by the other cohesin subunits 120. CTCF mediates gene regulation not only by forming intrachromosomal loops, but also by establishing and regulating specific contacts between different chromosomes99, 121, whose specificity may require other factors in addition to cohesin.

Thirdly, insulator proteins have been shown to associate to structural components of the nucleus. CTCF associates with the nuclear matrix 69, 122 through direct interactions with nucleophosmin 69. Further ChIP experiments showed that the presence of intact CTCF binding sites is required to recruit CTCF to the outer surface of the nucleolus 69. In analogy to the CTCF-nucleophosmin interaction, Su(Hw) is able to induce the formation of chromatin loops by tethering DNA to the nuclear lamina. Fluorescence microscopy experiments have shown that Su(Hw) localizes preferentially to the nuclear periphery 41 while immuno-precipitation assays have unveiled a network of interactions between Su(Hw), Mod(mdg4) and dTopors, the Drosophila homolog of the Topoisomerase I binding arginine-serine rich (RS) protein, that tethers Su(Hw) to the nuclear membrane through direct interactions with lamin 123. These findings suggest that insulator are tethered to the nuclear periphery by clusters of proteins held together by a vast network of interactions20.

The confinement of genetic material near the nuclear envelope is a shared feature between several insulators. Genome-wide DNA adenine methyltransferase identification (DamID)124 on Drosophila 46 and human cell lines 45 showed how large portions of the two genomes are found to reside along the nuclear envelope. These lamina associated domains (LADs) are characterized by low gene-expression levels and display enriched binding of Su(Hw) and human CTCF at their borders. Other insulator proteins in Drosophila, however, are depleted within LAD regions 45, consistent with their association with actively transcribed genes. It seems likely that in these cases the main function of Su(Hw) and CTCF is to prevent the spreading of chromatin repression to other regions of the genome. Taken together, the interactions of IBPs with the nuclear envelope 42 or with the lamina 45, 46 may also reflect the potential activation state of genes and/or their positions relative to chromosome territories. Upon activation, genes may often move away from the interior of chromosome territories, and the role of IBPs and co-factors remains to be determined in this context as IBPs bind mostly to inter-genic regions.

Post-transcriptional modifications

Insulator proteins often display post-translational modifications (PTMs) that change during the cell cycle and that can modulate their functions by directly affecting their interactions with co-factors and their DNA binding properties. For instance, in the gypsy insulator, SUMO-ylation (Small-Ubiquitin-like Modifier) of Mod(mdg4) and the regulatory protein CP190 are known to interfere with the barrier activity of Su(Hw) but not to influence its DNA-binding capacity 125.

CTCF display a large variety of post-transcriptional modifications: it is PAR(Poly-ADP-Ribose)-ylated and SUMOylated at its N-terminus and phosphorylated at its C-terminus. Similary to what was observed at the gypsy insulator, PAR-ylation of CTCF was shown to be involved in a positive regulation of insulator activity but not to influence its DNA-binding properties 115. These examples suggest that post-translational modifications are involved in the regulation of protein-protein interactions that mediate long-range interactions 126.

PTM have been also implicated in the regulation of the binding pattern of insulator proteins. The most notable example is that of CTCF, in which PTMs induce different conformational changes in the protein that lead to different combinations of zinc-fingers being used to bind distinct consensus sequences 68, 127.

Finally, other PTMs have been described that affect the function of IBPs by an unknown mechanism. CTCF phosphorylation and SUMO-ylation are involved in its repressive transcriptional function 127, 128, whereas phosphorylation of BEAF is involved in its association to the nuclear matrix 55.

7- Discussion

Future technological advances and their impact in the chromatin field

Recent advances in the chromatin field have been made possible through the combination of high-throughput sequencing used in combination with previous technological breakthroughs including ChIP and/or 3C and derivative technologies 48. However, current genome-wide methods have two inherent caveats. First, these methods require large sample sizes to increase precision by averaging, which works well for homogeneous populations. Thus, special care must be taken in the interpretation of results that may be derived from heterogeneous samples, as in this case averaging will not increase precision but rather decrease accuracy: for example a sample with two cell populations, one with a strong and the other with a weak protein binding peak at a specific locus, cannot be discerned from a single homogeneous population with a moderate peak. Second, fast dynamic processes are blurred: for instance, the binding ‘peaks’ of a given factor involved in a rapid process might only be apparent at the limited number of loci where this process is slow. Novel methodologies, such as single-cell genomics will certainly play an important role in the future, as they may allow for the genome-wide detection of protein binding sites, protein-protein interactions, and long-range contacts while not only avoiding sample heterogeneity, but rather providing a full measure of the degree of heterogeneity in a cell population. In particular, important advances in gene sequencing and measurement of protein levels in single-cells have already been achieved 129, and further extensions to Hi-C and ChIP technologies may be around the corner.

Fluorescence microscopy-based methods naturally avoid heterogeneous sampling and permit the observation of dynamical events. These methods have, currently, several limitations which considerably weaken this advantage. First, light diffraction limits the maximum resolving power of conventional microscopes to ~ 200-300 nm, making it impossible to determine the inner architecture of nuclear structures smaller than this resolution limit (e.g. replication/ transcription factories, or PcG bodies), or to determine whether different factors spatially co-localize at distances shorter than this limit. For instance, a recent publication clearly demonstrates that only at higher spatial resolutions can double layer invaginations of the nuclear membrane be detected and different components of the nuclear pore complex be differentially localized 130: proteins that in conventional images, due to the low resolution, seem to be bound to the nuclear envelope are in reality separated by almost 150 nm. Recent advances in fluorescence microscopy will surely drive important developments in the chromatin field. On the one hand, several methods referred to as super-resolution microscopies, have allowed for resolutions as high as 20 nm to be achieved 131. These methods will be important to determine the internal architecture of diffraction-limited nuclear structures (such as bodies), to unveil the spatial interrelationship between different nuclear structural components, and to more accurately pinpoint interactions between cofactors. On the other hand, fluorescence fluctuation methods, such as fluorescence cross-correlation spectroscopy, allow for the direct quantification of interactions between factors, a measure that is impossible by colocalization methods.

Secondly, current microscopy methods are limited in their ability to detect fast dynamics. Many of the factors involved in chromatin organization and transcription regulation rapidly fluctuate between a low mobility state (when they are associated to DNA or nuclear structures) and a fast diffusing, unbound state. Current microscopy methods are not well suited for these kind of studies (as signals from both fractions are mixed and can lead to artifactual interpretations) but current and future developments in single-particle tracking methods using photo-activable markers 132 may provide the means of exploring the dynamics of chromatin-associated enzymes during their different activities. Finally, further advances in the development of automated microscopy methods 133 will allow for higher throughput, more reliability through better statistics and standardization, and improved precision through the development of novel image treatment methods.

Roles of chromatin insulators in cell cycle and development

Classical models have postulated that insulators work either as heterochromatin barriers or enhancer blockers. However, recent studies have shown that these definitions may be promiscuous: barrier activities often necessitate long-range interactions and enhancer blocking may require chromatin remodeling functions. In addition, insulator binding proteins seem to be able to confer both activities depending on the chromatin context and interaction partners, and to couple chromatin organization at the level of nucleosomes with higher-order chromatin organization. Ultimately, it is clear that further mechanistic insights into the roles played by IBPs and insulators in transcription regulation and chromatin architecture will go hand in hand with new developments in the transcription field.

In addition to their role in transcription regulation, insulators may be important in remodeling chromosome architecture during stages of the cell cycle other than interphase. In addition to being key factors regulating the activity of insulators in interphase, IBPs and cohesin are present during S phase and mitosis 4, 102, 118. Recent work has actually shown that long-range interactions in S phase requires cohesin to cluster the DNA replication origins within factories 134. Given the link between cohesin binding and CTCF, this result further raises the possibility that IBPs might play a role in subsequent cell cycle phases. In addition to the well known binding pattern of cohesin to centromere regions 135, CTCF has also been found at these sites during metaphase 118, prompting a possible role of IBPs during chromosome organization during cell division. Biochemical and genetic identification of the distinct factors interacting with IBPs, as well as their binding patterns at different cell cycle stages will be key to clarify the possible global roles of IBPs in chromosome organization.

The gene activation/repression patterns induced by insulators might survive mitosis to maintain the epigenetic programs from one cell generation to the next but may also depend on development stage 136. By the interaction with cofactors like cohesin, insulator binding proteins are the first layer in creating inter- or intrachromosomal long range connections that influence gene expression 106, 108. Interestingly, transcript levels of dCTCF and BEAF show large variations during development in Drosophila137 (see also www.fymine.org). dCTCF and BEAF are upregulated during early embryonic stages, and downregulated in the larval state. Changes in the transcription levels of insulator proteins during different developmental stages could reflect their involvement in eventually regulating important developmental programs, as suggested by Bushey et al. 38. Future experiments, investigating both the binding patterns and networks of interaction partners of IBPs as well as their ability to organize chromatin by clustering, at different stages of development will be necessary to fully understand the role of insulator bodies in the maintenance of cell identity and differentiation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an European Research Council Starting Grant (M.N.), the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (O.C. and M.N.) and the Avenir/ARC program from the Institut National de la Santé et la Recherche Médicale (O.C.).

Bibliography

- 1.Elgin SC, Grewal SI. Heterochromatin: silence is golden. Curr Biol. 2003;13:R895–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Probst AV, Dunleavy E, Almouzni G. Epigenetic inheritance during the cell cycle. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:192–206. doi: 10.1038/nrm2640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sexton T, Bantignies F, Cavalli G. Genomic interactions: chromatin loops and gene meeting points in transcriptional regulation. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2009;20:849–55. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang HY, Cuvier O, Dekker J. Gene dates, parties and galas. Symposium on Chromatin Dynamics and Higher Order Organization. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:689–93. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mechali M. Eukaryotic DNA replication origins: many choices for appropriate answers. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:728–38. doi: 10.1038/nrm2976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Misteli T. Beyond the sequence: cellular organization of genome function. Cell. 2007;128:787–800. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Capelson M, Corces VG. Boundary elements and nuclear organization. Biol Cell. 2004;96:617–29. doi: 10.1016/j.biolcel.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fraser P. Transcriptional control thrown for a loop. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2006;16:490–5. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cavalli G. Chromosome kissing. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17:443–50. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu N, Tsai CL, Lee JT. Transient homologous chromosome pairing marks the onset of X inactivation. Science. 2006;311:1149–52. doi: 10.1126/science.1122984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spilianakis CG, Lalioti MD, Town T, Lee GR, Flavell RA. Interchromosomal associations between alternatively expressed loci. Nature. 2005;435:637–45. doi: 10.1038/nature03574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taddei A, Schober H, Gasser SM. The budding yeast nucleus. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a000612. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reitman M, Lee E, Westphal H, Felsenfeld G. Site-independent expression of the chicken beta A-globin gene in transgenic mice. Nature. 1990;348:749–52. doi: 10.1038/348749a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geyer PK, Corces VG. DNA position-specific repression of transcription by a Drosophila zinc finger protein. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1865–73. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.10.1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cai H, Levine M. Modulation of enhancer-promoter interactions by insulators in the Drosophila embryo. Nature. 1995;376:533–6. doi: 10.1038/376533a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Udvardy A, Maine E, Schedl P. The 87A7 chromomere. Identification of novel chromatin structures flanking the heat shock locus that may define the boundaries of higher order domains. J Mol Biol. 1985;185:341–58. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90408-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gyurkovics H, Gausz J, Kummer J, Karch F. A new homeotic mutation in the Drosophila bithorax complex removes a boundary separating two domains of regulation. EMBO J. 1990;9:2579–85. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07439.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kellum R, Schedl P. A group of scs elements function as domain boundaries in an enhancer-blocking assay. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:2424–31. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.5.2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao K, Hart CM, Laemmli UK. Visualization of chromosomal domains with boundary element-associated factor BEAF-32. Cell. 1995;81:879–89. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaszner M, Felsenfeld G. Insulators: exploiting transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:703–13. doi: 10.1038/nrg1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maeda RK, Karch F. Making connections: boundaries and insulators in Drosophila. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17:394–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Negre N, Brown CD, Ma L, Bristow CA, Miller SW, Wagner U, et al. A cis-regulatory map of the Drosophila genome. Nature. 2011;471:527–31. doi: 10.1038/nature09990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cuvier O, Hart CM, Laemmli UK. Identification of a class of chromatin boundary elements. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:7478–86. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.7478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donze D, Adams CR, Rine J, Kamakaka RT. The boundaries of the silenced HMR domain in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 1999;13:698–708. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.6.698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Noma K, Cam HP, Maraia RJ, Grewal SI. A role for TFIIIC transcription factor complex in genome organization. Cell. 2006;125:859–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raab JR, Kamakaka RT. Insulators and promoters: closer than we think. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:439–46. doi: 10.1038/nrg2765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaszner M, Vazquez J, Schedl P. The Zw5 protein, a component of the scs chromatin domain boundary, is able to block enhancer-promoter interaction. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2098–107. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.16.2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moon H, Filippova G, Loukinov D, Pugacheva E, Chen Q, Smith ST, et al. CTCF is conserved from Drosophila to humans and confers enhancer blocking of the Fab-8 insulator. EMBO Rep. 2005;6:165–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baniahmad A, Steiner C, Kohne AC, Renkawitz R. Modular structure of a chicken lysozyme silencer: involvement of an unusual thyroid hormone receptor binding site. Cell. 1990;61:505–14. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90532-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lobanenkov VV, Nicolas RH, Adler VV, Paterson H, Klenova EM, Polotskaja AV, et al. A novel sequence-specific DNA binding protein which interacts with three regularly spaced direct repeats of the CCCTC-motif in the 5′-flanking sequence of the chicken c-myc gene. Oncogene. 1990;5:1743–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wallace JA, Felsenfeld G. We gather together: insulators and genome organization. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17:400–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matharu NK, Hussain T, Sankaranarayanan R, Mishra RK. Vertebrate homologue of Drosophila GAGA factor. J Mol Biol. 2010;400:434–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lunyak VV, Prefontaine GG, Nunez E, Cramer T, Ju BG, Ohgi KA, et al. Developmentally regulated activation of a SINE B2 repeat as a domain boundary in organogenesis. Science. 2007;317:248–51. doi: 10.1126/science.1140871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.West AG, Huang S, Gaszner M, Litt MD, Felsenfeld G. Recruitment of histone modifications by USF proteins at a vertebrate barrier element. Mol Cell. 2004;16:453–63. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Emberly E, Blattes R, Schuettengruber B, Hennion M, Jiang N, Hart CM, et al. BEAF regulates cell-cycle genes through the controlled deposition of H3K9 methylation marks into its conserved dual-core binding sites. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:2896–910. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dhillon N, Raab J, Guzzo J, Szyjka SJ, Gangadharan S, Aparicio OM, et al. DNA polymerase epsilon, acetylases and remodellers cooperate to form a specialized chromatin structure at a tRNA insulator. EMBO J. 2009;28:2583–600. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bartkuhn M, Straub T, Herold M, Herrmann M, Rathke C, Saumweber H, et al. Active promoters and insulators are marked by the centrosomal protein 190. EMBO J. 2009;28:877–88. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bushey AM, Ramos E, Corces VG. Three subclasses of a Drosophila insulator show distinct and cell type-specific genomic distributions. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1338–50. doi: 10.1101/gad.1798209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Negre N, Brown CD, Shah PK, Kheradpour P, Morrison CA, Henikoff JG, et al. A comprehensive map of insulator elements for the Drosophila genome. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000814. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dickson J, Gowher H, Strogantsev R, Gaszner M, Hair A, Felsenfeld G, et al. VEZF1 elements mediate protection from DNA methylation. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000804. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gerasimova TI, Byrd K, Corces VG. A chromatin insulator determines the nuclear localization of DNA. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1025–35. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ishii K, Laemmli UK. Structural and dynamic functions establish chromatin domains. Mol Cell. 2003;11:237–48. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gerasimova TI, Lei EP, Bushey AM, Corces VG. Coordinated control of dCTCF and gypsy chromatin insulators in Drosophila. Mol Cell. 2007;28:761–72. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gohl D, Aoki T, Blanton J, Shanower G, Kappes G, Schedl P. Mechanism of chromosomal boundary action: roadblock, sink, or loop? Genetics. 2011;187:731–48. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.123752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guelen L, Pagie L, Brasset E, Meuleman W, Faza MB, Talhout W, et al. Domain organization of human chromosomes revealed by mapping of nuclear lamina interactions. Nature. 2008;453:948–51. doi: 10.1038/nature06947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Bemmel JG, Pagie L, Braunschweig U, Brugman W, Meuleman W, Kerkhoven RM, et al. The insulator protein SU(HW) fine-tunes nuclear lamina interactions of the Drosophila genome. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kalverda B, Fornerod M. Characterization of genome-nucleoporin interactions in Drosophila links chromatin insulators to the nuclear pore complex. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:4812–7. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.24.14328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dekker J, Rippe K, Dekker M, Kleckner N. Capturing chromosome conformation. Science. 2002;295:1306–11. doi: 10.1126/science.1067799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lieberman-Aiden E, van Berkum NL, Williams L, Imakaev M, Ragoczy T, Telling A, et al. Comprehensive mapping of long-range interactions reveals folding principles of the human genome. Science. 2009;326:289–93. doi: 10.1126/science.1181369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cremer T, Kreth G, Koester H, Fink RH, Heintzmann R, Cremer M, et al. Chromosome territories, interchromatin domain compartment, and nuclear matrix: an integrated view of the functional nuclear architecture. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2000;10:179–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Botta M, Haider S, Leung IX, Lio P, Mozziconacci J. Intra- and inter-chromosomal interactions correlate with CTCF binding genome wide. Mol Syst Biol. 2010;6:426. doi: 10.1038/msb.2010.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cuvier O, Hart CM, Kas E, Laemmli UK. Identification of a multicopy chromatin boundary element at the borders of silenced chromosomal domains. Chromosoma. 2002;110:519–31. doi: 10.1007/s00412-001-0181-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jiang N, Emberly E, Cuvier O, Hart CM. Genome-wide mapping of boundary element-associated factor (BEAF) binding sites in Drosophila melanogaster links BEAF to transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:3556–68. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01748-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hart CM, Zhao K, Laemmli UK. The scs’ boundary element: characterization of boundary element-associated factors. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:999–1009. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.2.999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pathak RU, Rangaraj N, Kallappagoudar S, Mishra K, Mishra RK. Boundary element-associated factor 32B connects chromatin domains to the nuclear matrix. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:4796–806. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00305-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Babu MM, Iyer LM, Balaji S, Aravind L. The natural history of the WRKY-GCM1 zinc fingers and the relationship between transcription factors and transposons. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:6505–20. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Holdridge C, Dorsett D. Repression of hsp70 heat shock gene transcription by the suppressor of hairy-wing protein of Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:1894–900. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.4.1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Roseman RR, Pirrotta V, Geyer PK. The su(Hw) protein insulates expression of the Drosophila melanogaster white gene from chromosomal position-effects. EMBO J. 1993;12:435–42. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05675.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smith PA, Corces VG. The suppressor of Hairy-wing protein regulates the tissue-specific expression of the Drosophila gypsy retrotransposon. Genetics. 1995;139:215–28. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.1.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Spana C, Harrison DA, Corces VG. The Drosophila melanogaster suppressor of Hairy-wing protein binds to specific sequences of the gypsy retrotransposon. Genes Dev. 1988;2:1414–23. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.11.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Harrison DA, Gdula DA, Coyne RS, Corces VG. A leucine zipper domain of the suppressor of Hairy-wing protein mediates its repressive effect on enhancer function. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1966–78. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.10.1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ghosh D, Gerasimova TI, Corces VG. Interactions between the Su(Hw) and Mod(mdg4) proteins required for gypsy insulator function. EMBO J. 2001;20:2518–27. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.10.2518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Adryan B, Woerfel G, Birch-Machin I, Gao S, Quick M, Meadows L, et al. Genomic mapping of Suppressor of Hairy-wing binding sites in Drosophila. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R167. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-8-r167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Parnell TJ, Kuhn EJ, Gilmore BL, Helou C, Wold MS, Geyer PK. Identification of genomic sites that bind the Drosophila suppressor of Hairy-wing insulator protein. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:5983–93. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00698-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kim TH, Abdullaev ZK, Smith AD, Ching KA, Loukinov DI, Green RD, et al. Analysis of the vertebrate insulator protein CTCF-binding sites in the human genome. Cell. 2007;128:1231–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Roh TY, Schones DE, Wang Z, et al. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell. 2007;129:823–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Renda M, Baglivo I, Burgess-Beusse B, Esposito S, Fattorusso R, Felsenfeld G, et al. Critical DNA binding interactions of the insulator protein CTCF: a small number of zinc fingers mediate strong binding, and a single finger-DNA interaction controls binding at imprinted loci. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:33336–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706213200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Filippova GN, Fagerlie S, Klenova EM, Myers C, Dehner Y, Goodwin G, et al. An exceptionally conserved transcriptional repressor, CTCF, employs different combinations of zinc fingers to bind diverged promoter sequences of avian and mammalian c-myc oncogenes. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2802–13. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.6.2802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yusufzai TM, Tagami H, Nakatani Y, Felsenfeld G. CTCF tethers an insulator to subnuclear sites, suggesting shared insulator mechanisms across species. Mol Cell. 2004;13:291–8. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pant V, Kurukuti S, Pugacheva E, Shamsuddin S, Mariano P, Renkawitz R, et al. Mutation of a single CTCF target site within the H19 imprinting control region leads to loss of Igf2 imprinting and complex patterns of de novo methylation upon maternal inheritance. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:3497–504. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.8.3497-3504.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Smith ST, Wickramasinghe P, Olson A, Loukinov D, Lin L, Deng J, et al. Genome wide ChIP-chip analyses reveal important roles for CTCF in Drosophila genome organization. Dev Biol. 2009;328:518–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.12.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Farkas G, Gausz J, Galloni M, Reuter G, Gyurkovics H, Karch F. The Trithorax-like gene encodes the Drosophila GAGA factor. Nature. 1994;371:806–8. doi: 10.1038/371806a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gilmour DS, Thomas GH, Elgin SC. Drosophila nuclear proteins bind to regions of alternating C and T residues in gene promoters. Science. 1989;245:1487–90. doi: 10.1126/science.2781290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Becker PB. Drosophila chromatin and transcription. Semin Cell Biol. 1995;6:185–90. doi: 10.1006/scel.1995.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Granok H, Leibovitch BA, Shaffer CD, Elgin SC. Chromatin. Ga-ga over GAGA factor. Curr Biol. 1995;5:238–41. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pedone PV, Ghirlando R, Clore GM, Gronenborn AM, Felsenfeld G, Omichinski JG. The single Cys2-His2 zinc finger domain of the GAGA protein flanked by basic residues is sufficient for high-affinity specific DNA binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:2822–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vaquero A, Blanch M, Espinas ML, Bernues J. Activation properties of GAGA transcription factor. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1779:312–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gerasimova TI, Gdula DA, Gerasimov DV, Simonova O, Corces VG. A Drosophila protein that imparts directionality on a chromatin insulator is an enhancer of position-effect variegation. Cell. 1995;82:587–97. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90031-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Georgiev PG, Gerasimova TI. [Detection of new genes participating in the trans-regulation of locus yellow of MDG-4 in Drosophila melanogaster] Genetika. 1989;25:1409–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pai CY, Lei EP, Ghosh D, Corces VG. The centrosomal protein CP190 is a component of the gypsy chromatin insulator. Mol Cell. 2004;16:737–48. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Oegema K, Whitfield WG, Alberts B. The cell cycle-dependent localization of the CP190 centrosomal protein is determined by the coordinate action of two separable domains. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:1261–73. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.5.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cuddapah S, Jothi R, Schones DE, Roh TY, Cui K, Zhao K. Global analysis of the insulator binding protein CTCF in chromatin barrier regions reveals demarcation of active and repressive domains. Genome Res. 2009;19:24–32. doi: 10.1101/gr.082800.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Martin D, Pantoja C, Minan AF, Valdes-Quezada C, Molto E, Matesanz F, et al. Genome-wide CTCF distribution in vertebrates defines equivalent sites that aid the identification of disease-associated genes. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Li B, Carey M, Workman JL. The role of chromatin during transcription. Cell. 2007;128:707–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Diesinger PM, Kunkel S, Langowski J, Heermann DW. Histone depletion facilitates chromatin loops on the kilobasepair scale. Biophys J. 2010;99:2995–3001. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Valenzuela L, Dhillon N, Dubey RN, Gartenberg MR, Kamakaka RT. Long-range communication between the silencers of HMR. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:1924–35. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01647-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gowher H, Stuhlmann H, Felsenfeld G. Vezf1 regulates genomic DNA methylation through its effects on expression of DNA methyltransferase Dnmt3b. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2075–84. doi: 10.1101/gad.1658408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chopra VS, Cande J, Hong JW, Levine M. Stalled Hox promoters as chromosomal boundaries. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1505–9. doi: 10.1101/gad.1807309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Core LJ, Lis JT. Transcription regulation through promoter-proximal pausing of RNA polymerase II. Science. 2008;319:1791–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1150843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gilchrist DA, Dos Santos G, Fargo DC, Xie B, Gao Y, Li L, et al. Pausing of RNA polymerase II disrupts DNA-specified nucleosome organization to enable precise gene regulation. Cell. 2010;143:540–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wu CH, Yamaguchi Y, Benjamin LR, Horvat-Gordon M, Washinsky J, Enerly E, et al. NELF and DSIF cause promoter proximal pausing on the hsp70 promoter in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1402–14. doi: 10.1101/gad.1091403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hainer SJ, Pruneski JA, Mitchell RD, Monteverde RM, Martens JA. Intergenic transcription causes repression by directing nucleosome assembly. Genes Dev. 2011;25:29–40. doi: 10.1101/gad.1975011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wan LB, Bartolomei MS. Regulation of imprinting in clusters: noncoding RNAs versus insulators. Adv Genet. 2008;61:207–23. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2660(07)00007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Blanton J, Gaszner M, Schedl P. Protein:protein interactions and the pairing of boundary elements in vivo. Genes Dev. 2003;17:664–75. doi: 10.1101/gad.1052003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ringrose L, Paro R. Epigenetic regulation of cellular memory by the Polycomb and Trithorax group proteins. Annu Rev Genet. 2004;38:413–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.091907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Li HB, Muller M, Bahechar IA, Kyrchanova O, Ohno K, Georgiev P, et al. Insulators, not Polycomb response elements, are required for long-range interactions between Polycomb targets in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:616–25. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00849-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chung JH, Bell AC, Felsenfeld G. Characterization of the chicken beta-globin insulator. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:575–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kurukuti S, Tiwari VK, Tavoosidana G, Pugacheva E, Murrell A, Zhao Z, et al. CTCF binding at the H19 imprinting control region mediates maternally inherited higher-order chromatin conformation to restrict enhancer access to Igf2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:10684–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600326103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ling JQ, Li T, Hu JF, Vu TH, Chen HL, Qiu XW, et al. CTCF mediates interchromosomal colocalization between Igf2/H19 and Wsb1/Nf1. Science. 2006;312:269–72. doi: 10.1126/science.1123191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Court F, Baniol M, Hagege H, Petit JS, Lelay-Taha MN, Carbonell F, et al. Long-range chromatin interactions at the mouse Igf2/H19 locus reveal a novel paternally expressed long non-coding RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tchurikov NA, Kretova OV, Moiseeva ED, Sosin DV. Evidence for RNA synthesis in the intergenic region between enhancer and promoter and its inhibition by insulators in Drosophila melanogaster. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:111–22. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nasmyth K, Haering CH. Cohesin: its roles and mechanisms. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:525–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Dorsett D. Cohesin: genomic insights into controlling gene transcription and development. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2011;21:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2011.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rollins RA, Morcillo P, Dorsett D. Nipped-B, a Drosophila homologue of chromosomal adherins, participates in activation by remote enhancers in the cut and Ultrabithorax genes. Genetics. 1999;152:577–93. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.2.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Dorsett D. Roles of the sister chromatid cohesion apparatus in gene expression, development, and human syndromes. Chromosoma. 2007;116:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s00412-006-0072-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Parelho V, Hadjur S, Spivakov M, Leleu M, Sauer S, Gregson HC, et al. Cohesins functionally associate with CTCF on mammalian chromosome arms. Cell. 2008;132:422–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mishiro T, Ishihara K, Hino S, Tsutsumi S, Aburatani H, Shirahige K, et al. Architectural roles of multiple chromatin insulators at the human apolipoprotein gene cluster. EMBO J. 2009;28:1234–45. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wendt KS, Yoshida K, Itoh T, Bando M, Koch B, Schirghuber E, et al. Cohesin mediates transcriptional insulation by CCCTC-binding factor. Nature. 2008;451:796–801. doi: 10.1038/nature06634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Degner SC, Verma-Gaur J, Wong TP, Bossen C, Iverson GM, Torkamani A, et al. CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF) and cohesin influence the genomic architecture of the Igh locus and antisense transcription in pro-B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:9566–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019391108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Byrd K, Corces VG. Visualization of chromatin domains created by the gypsy insulator of Drosophila. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:565–74. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200305013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Akbari OS, Oliver D, Eyer K, Pai CY. An Entry/Gateway cloning system for general expression of genes with molecular tags in Drosophila melanogaster. BMC Cell Biol. 2009;10:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-10-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Dorman ER, Bushey AM, Corces VG. The role of insulator elements in large-scale chromatin structure in interphase. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2007;18:682–90. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Chodagam S, Royou A, Whitfield W, Karess R, Raff JW. The centrosomal protein CP190 regulates myosin function during early Drosophila development. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1308–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Iwasaki O, Tanaka A, Tanizawa H, Grewal SI, Noma K. Centromeric localization of dispersed Pol III genes in fission yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:254–65. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-09-0790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Yu W, Ginjala V, Pant V, Chernukhin I, Whitehead J, Docquier F, et al. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation regulates CTCF-dependent chromatin insulation. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1105–10. doi: 10.1038/ng1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Mohan M, Bartkuhn M, Herold M, Philippen A, Heinl N, Bardenhagen I, et al. The Drosophila insulator proteins CTCF and CP190 link enhancer blocking to body patterning. EMBO J. 2007;26:4203–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Gerasimova TI, Corces VG. Polycomb and trithorax group proteins mediate the function of a chromatin insulator. Cell. 1998;92:511–21. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80944-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Rubio ED, Reiss DJ, Welcsh PL, Disteche CM, Filippova GN, Baliga NS, et al. CTCF physically links cohesin to chromatin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:8309–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801273105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Stedman W, Kang H, Lin S, Kissil JL, Bartolomei MS, Lieberman PM. Cohesins localize with CTCF at the KSHV latency control region and at cellular c-myc and H19/Igf2 insulators. EMBO J. 2008;27:654–66. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Xiao T, Wallace J, Felsenfeld G. Specific Sites in the C Terminus of CTCF Interact with the SA2 Subunit of the Cohesin Complex and Are Required for Cohesin-Dependent Insulation Activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:2174–83. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05093-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Zhao Z, Tavoosidana G, Sjolinder M, Gondor A, Mariano P, Wang S, et al. Circular chromosome conformation capture (4C) uncovers extensive networks of epigenetically regulated intra- and interchromosomal interactions. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1341–7. doi: 10.1038/ng1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Dunn KL, Zhao H, Davie JR. The insulator binding protein CTCF associates with the nuclear matrix. Exp Cell Res. 2003;288:218–23. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00185-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Capelson M, Corces VG. The ubiquitin ligase dTopors directs the nuclear organization of a chromatin insulator. Mol Cell. 2005;20:105–16. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.van Steensel B, Henikoff S. Identification of in vivo DNA targets of chromatin proteins using tethered dam methyltransferase. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:424–8. doi: 10.1038/74487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Capelson M, Corces VG. SUMO conjugation attenuates the activity of the gypsy chromatin insulator. EMBO J. 2006;25:1906–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Klenova E, Ohlsson R. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation and epigenetics. Is CTCF PARt of the plot? Cell Cycle. 2005;4:96–101. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.1.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Ohlsson R, Lobanenkov V, Klenova E. Does CTCF mediate between nuclear organization and gene expression? Bioessays. 2010;32:37–50. doi: 10.1002/bies.200900118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.MacPherson MJ, Beatty LG, Zhou W, Du M, Sadowski PD. The CTCF insulator protein is posttranslationally modified by SUMO. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:714–25. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00825-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]