Abstract

Objective

To provide clinicians with an update on the diagnosis of celiac disease (CD) and to make recommendations on the indications to screen for CD in patients presenting with low bone mineral density (BMD) or fragility fractures.

Quality of evidence

A multidisciplinary task force developed clinically relevant questions related to the diagnosis of CD as the basis for a literature search of the MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CENTRAL databases (January 2000 to January 2009) using the key words celiac disease, osteoporosis, osteopenia, low bone mass, and fracture. The existing literature consists of level I and II studies.

Main message

The estimated prevalence of asymptomatic CD is 2% to 3% in individuals with low BMD. Routine screening for CD is not justified in patients with low BMD. However, targeted screening for CD is recommended for patients who have T-scores of −1.0 or less at the spine or hip, or a history of fragility fractures in association with any CD-related symptoms or conditions; family history of CD; or low urinary calcium levels, vitamin D insufficiency, and raised parathyroid hormone levels despite adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D. Celiac disease testing should be performed while the subject is consuming a gluten-containing diet; initial screening should be performed with human recombinant immunoglobulin (Ig) A tissue transglutaminase or other IgA tissue transglutaminase assays, in association with IgA endomysial antibody immunofluorescence. Duodenal biopsy is necessary to confirm the diagnosis of CD. Human leukocyte antigen typing might assist in confirming or ruling out the diagnosis of CD in cases where serology and histology are discordant. Definitive diagnosis is based on clinical, serologic, and histologic features, combined with a positive response to a gluten-free diet.

Conclusion

Current evidence does not support routine screening for CD in all patients with low BMD. A targeted case-finding approach is appropriate for patients who are at higher risk of CD.

Celiac disease (CD) is a genetic autoimmune enteropathy caused by an immune response to gluten. Classically, CD presents with chronic diarrhea, abdominal pain, and malabsorption. The small bowel undergoes mucosal atrophy and inflammation, which improve when consuming a gluten-free diet (GFD).1–4 The clinical spectrum of CD is broad, with marked differences in symptom severity and histology.1–6 According to a recent systematic review, the prevalence of CD is close to 1% worldwide.7–12 Children often present with diarrhea, abdominal distention, and failure to thrive; adolescents and adults present more commonly with mild gastrointestinal symptoms for years.13,14 Celiac disease might also be completely asymptomatic (silent form), detected only by serologic screening or serendipitously during an upper endoscopy.

Patients presenting with osteoporosis, manifested either by low bone mineral density (BMD) on dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry scans or by fragility fractures, should be evaluated for secondary causes, including CD.15–17 Celiac disease causes secondary hyperparathyroidism and osteomalacia from calcium and vitamin D malabsorption.18–20 Markers of bone resorption increase and are not balanced by markers of bone formation, resulting in net bone loss.21 Chronic inflammation with increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines and decreased levels of inhibitory cytokines causes bone loss owing to direct effects on osteoclastogenesis and osteoblast activity.22–27 An increased receptor activator of NFκB ligand to osteoprotegerin ratio has also been implicated.21,28 Hypogonadism associated with CD might also contribute to bone loss.29

Patients with CD are at increased risk of fractures, particularly in the peripheral skeleton.30,31 A recent meta-analysis showed the pooled odds ratios for all fractures in CD patients was 1.43 compared with control groups.32 Many studies show substantial improvement in BMD after introduction of a GFD.33–36

Given the above information, it is plausible that early diagnosis of CD in patients with low BMD could help in fracture prevention. However, no data indicate increased risk of fractures among CD patients detected by screening,37 and there are no direct studies on the effect of a GFD on fracture risk. Consequently, there is currently no consensus on whether to screen for CD in patients with low BMD. Recognition of the need for evidence-based approaches in this field led to the establishment of a multidisciplinary Canadian task force that was charged with reviewing the relevant literature and providing clinical guidance for the diagnosis of CD in individuals with low BMD or fragility fractures. The initiative was led and supported by the Calcium Disorders Clinic of St Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton at McMaster University in Ontario, in association with members of relevant national societies. The main focus of this review is on the adult population.

Quality of evidence

We conducted a literature search of the MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CENTRAL databases from January 2000 to January 2009 using the key words celiac disease, osteoporosis, osteopenia, low bone mass, and fracture. All relevant papers on the relationship between osteoporosis and CD, and on CD prevalence and diagnosis were considered for inclusion. International guidelines on CD published after 2000 were reviewed. The quality of evidence was graded according to the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (Box 1).38 The quality of evidence is good for some questions and fair or nonexistent for others.

Box 1. Levels of evidence adapted from the Canadian task Force on preventive Health Care.

| Level I: At least 1 properly conducted randomized controlled trial, systematic review, or meta-analysis |

| Level II: Other comparison trials, non-randomized, cohort, case-control, or epidemiologic studies, and preferably more than 1 study |

| Level III: Expert opinion or consensus statement |

Adapted from the Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination.38

How is CD diagnosed?

No single test is diagnostic of CD; a definitive diagnosis requires clinical evaluation, serologic tests, and duodenal biopsy, often supplemented by clinical or histologic response to a GFD. Serologic, clinical, and histologic findings are discordant in about 10% of cases.2 Initial testing should be performed while consuming a full gluten-containing diet, as withdrawal of gluten might lead to false-negative results.

Serologic tests

Currently, the best available tests are immunoglobulin (Ig) A tissue transglutaminase (tTG) and IgA endomysial antibody (EMA) immunofluorescence. Both have comparable diagnostic accuracy, with a specificity close to 100% and sensitivities between 90% and 98%.39 Immunoglobulin A tTG testing is preferred because it is automated, less expensive, and quicker. Immunoglobulin A tTG testing has been validated in clinical practice and is an excellent tool for excluding the diagnosis of CD in low- or intermediate-risk populations.40

Testing for IgG antibodies of EMA and tTG has generally lower sensitivity,6,39 being more useful to detect CD in IgA-deficient patients.41,42

Antigliadin antibody testing is no longer routinely recommended because of its lower sensitivity (less than 80%) and specificity (80% to 90%).6,39

Histologic tests

The criterion standard for diagnosing CD is villous atrophy on duodenal biopsy. A standardized histology report based on the modified Marsh criteria is recommended (Table 1).43–45 As mucosal changes can be patchy, at least 4 to 6 biopsy specimens should be taken to ensure optimal test sensitivity.46,47 False-negative results might also occur in patients taking immunosuppressants, taking corticosteroids, or consuming a GFD. Histologic findings are characteristic of but not specific for CD; they occur in tropical sprue, HIV enteropathy, Giardia lamblia infestation, and common variable immunodeficiency.

Table 1.

Histologic grading of duodenal mucosal changes in celiac disease according to modified Marsh criteria

| STAGE | MUCOSAL CHANGE | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Normal | Normal mucosal architecture |

| I | Infiltrative | Normal mucosal architecture Villous epithelium is infiltrated by lymphocytes (> 30 per 100 enterocytes) |

| II | Hyperplastic | Crypt hyperplasia with infiltration of inflammatory cells |

| III | Villous atrophy | |

| IIIa | • Partial | Shortened blunt villi associated with mild infiltration of lymphocytes and crypt hyperplasia |

| IIIb | • Subtotal | Clearly atrophic villi but still recognizable Signs of crypt hyperplasia and inflammatory cell infiltration are increased |

| IIIc | • Total | Nearly total absence of villi Severe atrophic, hyperplastic, and infiltrative lesions |

| IV | Hypoplastic | Total villous atrophy Crypt hypoplasia Normal intraepithelial lymphocyte count |

Adapted from Buchman.45

Human leukocyte antigen typing

If serology and histology are discordant, human leukocyte antigen (HLA) typing might be useful in diagnosis, as HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8 are present in almost all individuals with CD but only in 30% to 40% of the general population. Thus, the absence of these alleles has a high negative predictive value, virtually excluding the diagnosis of CD.48 Human leukocyte antigen typing is also useful in selecting what first-degree relatives are at risk of CD and could benefit from longitudinal screening for CD by serology.2

Who should be tested for CD?

The role of mass screening for CD remains controversial45,49,50; proponents cite the high prevalence of CD, and associated malignancy and fragility fractures. Conversely, opponents cite a lack of knowledge about the progression of asymptomatic CD, poor compliance with diet in individuals whose CD is detected by screening, and impaired quality of life with a lifelong GFD in otherwise asymptomatic patients. It has therefore been proposed that screening be reserved for those at higher risk of CD.51

Do patients presenting with low BMD have increased risk of CD?

We updated the data from an earlier systematic review on the prevalence of CD diagnosed by screening among patients with low BMD7 using the same search strategy and inclusion criteria for studies up to June 2008. Eight studies were included and CD prevalence ranged from 0% to 3.4% (Table 2).52–59 Only 4 studies applied the same screening algorithm to patients with low BMD and control groups. They generally showed a higher prevalence of CD among patients with low BMD (Table 3).52,53,57,58 Based on these results, a reasonable estimate of the prevalence of CD is 2% to 3% in low-BMD populations, compared with 1% or less in the general population.

Table 2.

Prevalence of CD detected by screening in patients presenting with low bone mineral density

| AUTHOR, YEAR, COUNTRY | T-SCORE | SAMPLE SIZE | FEMALE SEX, % | AGE, Y | SCREENING ALGORITHM | BIOPSY CRITERIA | CD PREVALENCE (95% CI), % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drummond et al,52 2003, Ireland | ≤ −1.0 | 366 | 100 | Mean 56 (SD 11.5; range 28–96) | IgA EMA and IgA tTG | NA | 2.2 (1.1–4.2) |

| González et al,53 2002, Argentina | < −2.5 | 127 | 100 | Mean 68 (range 50–82) | 1. IgA AGA 2. IgA EMA |

Marsh III | 0.8 (0.02–4.31) |

| Lindh et al,54 1992, Sweden | NA | 92 | 91 | Mean 66 (SD 12) | IgA AGA | NA | 3.3 (1.1–9.1) |

| Mather et al,55 2001, Canada | ≤ −1.0 | 96 | 81 | Mean 57 (range 18–86) | IgA EMA | NA | 0 (0–3.8) |

| Nuti et al,56 2001, Italy | ≤ −2.5 | 255 | 100 | Mean 66 (SD 8.5) | 1. IgA AGA 2. IgA tTG |

NA | 2.3 (1.1–5.0) |

| Sanders et al,57 2005, United Kingdom | ≤ −1.0 | 674 | 95 | Mean 53 (range 21–69) | IgA AGA and IgA EMA | ESPGHAN | 1.5 (0.8–2.7) |

| Stenson et al,58 2005, United States | ≤ −2.5 | 266 | 90 | Mean 57 (SD 12) | IgA EMA and IgA tTG | Marsh III | 3.4 (1.8–6.3) |

| Karakan et al,59 2007, Turkey | ≤ −1.0 | 135 | 90 | Mean 57.2 (range 24–81) | IgA EMA | NA | 0 (0–2.7) |

AGA—antigliadin antibody, CD—celiac disease, EMA—endomysial antibody, ESPGHAN—European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Ig—immunoglobulin, NA—not available, tTG—tissue transglutaminase.

Table 3.

Risk of CD in patients with low BMD compared with control groups evaluated by the same screening algorithms

| AUTHOR, YEAR, COUNTRY | CHARACTERISTICS OF PATIENTS WITH LOW BMD | CHARACTERISTICS OF CONTROL GROUP | CD PREVALENCE IN PATIENTS WITH LOW BMD, % (CASES/N) | CD PREVALENCE IN CONTROL GROUP, % (CASES/N) | P VALUE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drummond et al,52 2003, Ireland | 366 women (82% postmenopausal) attending a bone densitometry unit Mean age 56 y (range 28–96 y) T-score ≤ −1.0 |

89 women (45% postmenopausal) attending the same bone densitometry unit T-score > −1.0 |

2.2 (8/366) | 0 (0/89) | .364 |

| González et al,53 2002, Argentina | 127 postmenopausal women Mean age 68 y (range 50–82 y) T-score < −2.5 |

747 women, mean age 29 y (range 16–79 y) attending an obligatory prenuptial examination in the same geographic area | 0.8 (1/127) | 0.8 (6/747) | > .99 |

| Sanders et al,572005, United Kingdom | 674 individuals (95% women) referred for DEXA scan from primary or secondary care Mean age 53 y (range 21–69 y) Total group: T-score ≤ −1.0 |

304 individuals of the same population T-score > −1.0 |

1.5 (10/674) | 0.7 (2/304) | .360 |

| Osteopenia: T-score −2.5 ≤ −1.0 | 1.2 (5/431) | 0.7 (2/304) | .7058 | ||

| Osteoporosis: T-score ≤ −2.5 | 2.1 (5/243) | 0.7 (2/304) | .2505 | ||

| Stenson et al,582005, United States | 266 individuals (90% female, most postmenopausal) attending a university bone clinic Mean age 57 y T-score ≤ −2.5 |

574 individuals (90% female, most postmenopausal) attending the same clinic Mean age 63.2 y T-score > −2.5 |

3.4 (9/266) | 0.2 (1/574) | < .001 |

BMD—bone mineral density, CD—celiac disease, DEXA—dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry.

Are specific groups of patients with low BMD at higher risk of CD?

Several studies have correlated the severity of CD with the severity of bone loss. It appears that CD is more likely to be diagnosed in patients with low BMD if they have T-scores of −2.5 or less, elevated parathyroid hormone levels, or vitamin D insufficiency56–58 and unexplained gastrointestinal symptoms.57,58 However, further research is required to confirm these predictors.

Should all patients with low BMD be screened for CD?

To date, there are no studies on the cost effectiveness of routine screening for CD in patients with low BMD. Current data suggest that serologic screening would not be cost effective in this population with low CD prevalence, as it would lead to many false-positive results, requiring additional unnecessary testing. Adding HLA typing to patients with positive serology results would reduce false-positive cases.48 However, the cost effectiveness of such an approach is unknown. Current evidence does not support routine screening for CD in all patients with low BMD, although this does not preclude a targeted case-finding approach, as described below.

Screening for CD: targeted case-finding approach

Clinical suspicion of CD increases with CD-associated symptoms, family history, and associated disorders.1,3,7 Table 4 describes the prevalence of CD among individuals with these conditions.3,7,60–66

Table 4.

Conditions associated with increased risk of CD

| CONDITION | CD PREVALENCE, % | REFERENCES |

|---|---|---|

| Dermatitis herpetiformis* | 69.0–89.0 | Hopper et al3 |

| First-degree relatives of individuals with known CD | 4.0–12.0 | Dubé et al7 |

| Iron deficiency anemia | 2.3–8.7 | Dubé et al7 |

| Unexplained infertility | 2.1–4.1 | Dubé et al7 |

| Unexplained elevation of transaminase levels | 1.5–9.0 | Dubé et al7 |

| Type 1 diabetes | 1–11 | Dubé et al7 |

| Autoimmune liver disease | 0.0–6.4 | Dubé et al7 |

| Autoimmune thyroiditis | 1.5–6.7 | Dubé et al7 |

| Addison disease | 1.2–11.0 | Betterle et al,60,61 Myhre et al62 |

| Ataxia of unknown cause | 1.9–16.0 | Bushara63 |

| Down syndrome | 3.0–12.0 | Dubé et al7 |

| Turner syndrome | 2.0–10.0 | Dubé et al7 |

| Idiopathic recurrent aphthous ulcers | 5.0 | Jokinen et al64 |

| Alopecia areata | 1.0–2.0 | Corazza et al,65 Fessatou et al66 |

| Low bone mineral density | 0.0–3.4 | Discussed in the text |

CD—celiac disease.

Patients with this condition should undergo duodenal biopsy irrespective of whether serologic testing for CD is performed.

Box 2 lists indications for CD screening in patients with low BMD or fragility fractures.15 We believe it is reasonable to screen patients who present with low urinary calcium, secondary hyperparathyroidism, or vitamin D insufficiency despite adequate daily intake of calcium and vitamin D.15 We set the screening threshold at a T-score of −1.0 or less instead of −2.5 or less owing to the lack of strong evidence to exclude osteopenic patients from screening. As bisphosphonate malabsorption might occur in CD, it seems reasonable to also consider those who do not respond to bisphosphonate therapy for CD screening.

Box 2. Indications for serologic screening for CD in patients with low BMD (T-score less than −1.0) or history of fragility fractures.

|

BMD—bone mineral density, CD—celiac disease.

Adequate daily intake of calcium and vitamin D as defined by Osteoporosis Canada (vitamin D3 at least 800 IU and 400 IU for individuals older and younger than 50 y, respectively, and elemental calcium ≥ 1000 mg).15

Patients with these symptoms should undergo duodenal biopsy irrespective of whether serologic testing for CD is performed.

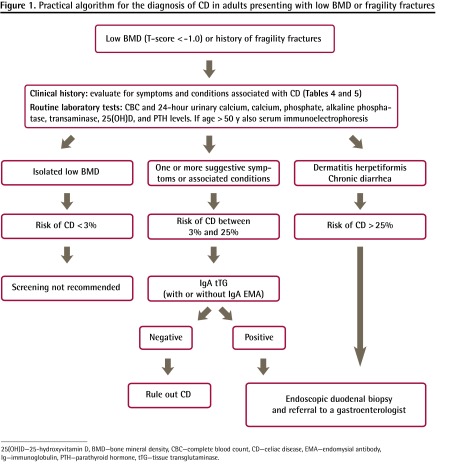

Study algorithm

Figure 1 shows a proposed study algorithm for the diagnosis of CD in patients with low BMD (T-score of −1.0 or less) or fragility fractures.

Figure 1.

Practical algorithm for the diagnosis of CD in adults presenting with low BMD or fragility fractures

25(OH)D—25-hydroxyvitamin D, BMD—bone mineral density, CBC—complete blood count, CD—celiac disease, EMA—endomysial antibody, Ig—immunoglobulin, PTH—parathyroid hormone, tTG—tissue transglutaminase.

We proposed a cutoff value of 25% to classify patients as being at low or high risk of CD. The reader can estimate the risk (pretest probability) of CD for an individual case, based on the data on prevalence of CD associated with different symptoms and conditions (Table 4).3,7,60–66

For the high-risk group (CD risk greater than 25%), individuals with dermatitis herpetiformis, chronic diarrhea, or unexplained weight loss have CD prevalences ranging between 25% and 89%.2,3,7

When the prevalence of disease (pretest probability) is high, the negative predictive value of a test decreases (ie, a negative test cannot rule out the diagnosis). As up to 9% of these patients can be seronegative for tTG and EMA, they should undergo intestinal biopsy independent of serology results.44,67–69

Most cases fall into the low-risk group (CD risk lower than 25%). These patients have at least 1 symptom or condition associated with CD (Table 4 and Box 2).3,7,15,60–66 Human recombinant IgA tTG or IgA EMA should be measured. If the serologic test results are positive, then a biopsy should be performed.70

Which serologic test should be used?

Clinical examples of how serologic tests perform and how to use the likelihood ratio (LHR) monogram are available from CFPlus.* Immunoglobulin A tTG and IgA EMA tests have excellent accuracy, with the LHR+ being above 40 and the LHR− close to 0.02. However, they perform variably according to the specific assay used. Human recombinant IgA tTG is the best single test for screening asymptomatic people and for excluding CD in symptomatic individuals with a low pretest probability of having CD (ie, < 25%).6,70–72 If this assay is not available, a combination of the IgA tTG assay (or any other assay) and the IgA EMA assay would also be appropriate.40,73

Is a confirmatory biopsy always necessary?

We recommend that patients with positive serology results undergo a confirmatory biopsy. Although the serologic test has excellent specificity, these results alone are not sufficient, as most cases in the primary care setting have low pretest probabilities (pretest probability of CD has to be greater than 35% for posttest probability to be greater than 95%).6 Further, the diagnosis of CD has lifelong implications in terms of costs and inconveniences of a GFD.

Conclusion

The prevalence of CD among patients with low BMD is probably higher than in the general population (level I evidence). Routine screening for CD in patients with low BMD is not justified (level III evidence). In adults with low BMD (T-score less than −1.0 at the spine or hip) or fragility fractures, a targeted case-finding approach is recommended. A T-score of −2.5 or less should prompt a high index of suspicion for CD, as CD is often silent or atypical in adults. A positive family history or any symptoms or conditions associated with CD should prompt screening (level II evidence).

Low urinary calcium level, vitamin D insufficiency, or elevated parathyroid hormone level despite adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D is an indication for CD screening (level II evidence).

Testing for CD should be performed with the patient consuming a gluten-containing diet (level II evidence). Initial CD screening should be performed with human recombinant IgA tTG or other IgA tTG assays in association with IgA EMA assays (level II evidence).

Endoscopy with 4 to 6 duodenal biopsies is necessary as a confirmatory test in most cases (level I evidence). A definitive diagnosis of CD requires consideration of clinical, serologic, and histologic features supplemented, if necessary, by documentation of a positive response to a GFD (level III evidence).

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

Patients presenting with osteoporosis, manifested either by low bone mineral density on dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry scans or by fragility fractures, should be evaluated for secondary causes including celiac disease (CD).

The best available tests are immunoglobulin A tissue transglutaminase and immunoglobulin A endomysial antibody immunofluorescence. The criterion standard test for diagnosing CD is villous atrophy on duodenal biopsy. If serology and histology results are discordant, human leukocyte antigen typing might be useful in diagnosis.

A T-score of −2.5 or less should prompt a high index of suspicion for CD, as CD is often silent or atypical in adults. A positive family history or any symptoms or conditions associated with CD should prompt screening.

Footnotes

This article is eligible for Mainpro-M1 credits. To earn credits, go to www.cfp.ca and click on the Mainpro link.

This article has been peer reviewed.

La traduction en français de cet article se trouve à www.cfp.ca dans la table des matières du numéro d’octobre 2013 à la page e441.

Clinical examples of how serologic tests perform and how to use the likelihood ratio monogram are available at www.cfp.ca. Go to the full text of the article online and click on CFPlus in the menu at the top right-hand side of the page.

Contributors

All authors contributed to the literature review and interpretation, and to preparing the manuscript for submission.

Competing interests

None declared

References

- 1.Green PH, Jabri B. Celiac disease. Annu Rev Med. 2006;57:207–21. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.57.051804.122404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green PH, Cellier C. Celiac disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(17):1731–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hopper AD, Hadjivassiliou M, Butt S, Sanders DS. Adult coeliac disease. BMJ. 2007;335(7619):558–62. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39316.442338.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Heel DA, West J. Recent advances in coeliac disease. Gut. 2006;55(7):1037–46. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.075119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lo W, Sano K, Lebwohl B, Diamond B, Green PH. Changing presentation of adult celiac disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48(2):395–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1021956200382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rostom A, Murray JA, Kagnoff MF. American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute technical review on the diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(6):1981–2002. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dubé C, Rostom A, Sy R, Cranney A, Saloojee N, Garritty C, et al. The prevalence of celiac disease in average-risk and at-risk Western European populations: a systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(4 Suppl 1):S57–67. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shahbazkhani B, Malekzadeh R, Sotoudeh M, Moghadam KF, Farhadi M, Ansari R, et al. High prevalence of coeliac disease in apparently healthy Iranian blood donors. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15(5):475–8. doi: 10.1097/01.meg.0000059118.41030.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tatar G, Elsurer R, Simsek H, Balaban YH, Hascelik G, Ozcebe OI, et al. Screening of tissue transglutaminase antibody in healthy blood donors for celiac disease screening in the Turkish population. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49(9):1479–84. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000042250.59327.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sood A, Midha V, Sood N, Malhotra V. Adult celiac disease in northern India. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2003;22(4):124–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Catassi C, Rätsch IM, Gandolfi L, Pratesi R, Fabiani E, El Asmar R, et al. Why is coeliac disease endemic in the people of the Sahara? Lancet. 1999;354(9179):647–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)02609-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gomez JC, Selvaggio GS, Viola M, Pizarro B, la Motta G, de Barrio S, et al. Prevalence of celiac disease in Argentina: screening of an adult population in the La Plata area. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(9):2700–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cranney A, Zarkadas M, Graham ID, Butzner JD, Rashid M, Warren R, et al. The Canadian Celiac Health Survey. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52(4):1087–95. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9258-2. Epub 2007 Feb 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green PHR, Stavropoulos SN, Panagi SG, Goldstein SL, McMahon DJ, Absan H, et al. Characteristics of adult celiac disease in the USA: results of a national survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(1):126–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papaioannou A, Morin S, Cheung AM, Atkinson S, Brown JP, Feldman S, et al. 2010 clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in Canada: summary. CMAJ. 2010;182(17):1864–73. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.100771. Epub 2010 Oct 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Catassi C, Rätsch IM, Fabiani E, Rossini M, Bordicchia F, Candela F, et al. Coeliac disease in the year 2000: exploring the iceberg. Lancet. 1994;343(8891):200–3. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90989-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fasano A, Catassi C. Current approaches to diagnosis and treatment of celiac disease: an evolving spectrum. Gastroenterology. 2001;120(3):636–51. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.22123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fiore CE, Pennisi P, Ferro G, Ximenes B, Privitelli L, Mangiafico RA, et al. Altered osteoprotegerin/RANKL ratio and low bone mineral density in celiac patients on long-term treatment with gluten-free diet. Horm Metab Res. 2006;38(6):417–22. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-944548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kemppainen T, Kröger H, Janatuinen E, Arnala I, Kosma VM, Pikkarainen P, et al. Osteoporosis in adult patients with celiac disease. Bone. 1999;24(3):249–55. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(98)00178-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valdimarsson T, Toss G, Löfman O, Ström M. Three years’ follow-up of bone density in adult coeliac disease: significance of secondary hyperparathyroidism. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35(3):274–80. doi: 10.1080/003655200750024146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keaveny AP, Freaney R, McKenna MJ, Masterson J, O’Donoghue DP. Bone remodeling indices and secondary hyperparathyroidism in celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91(6):1226–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fornari MC, Pedreira S, Niveloni S, González D, Diez RA, Vánquez H, et al. Preand post-treatment serum levels of cytokines, IL-1beta, IL-6, and IL-1 receptor antagonist in celiac disease. Are they related to the associated osteopenia? Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93(3):413–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Di Stefano M, Sciarra G, Jorizzo RA, Grillo RL, Cecchetti L, Speziale D, et al. Local and male gonadal factors in the pathogenesis of coeliac bone loss. Ital J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;29(Suppl 2):31. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taranta A, Fortunati D, Longo M, Rucci N, lacomino E, Aliberti F, et al. Imbalance of osteoclastogenesis-regulating factors in patients with celiac disease. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19(7):1112–21. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040319. Epub 2004 Mar 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horwood NJ, Elliott J, Martin TJ, Gillespie MT. IL-12 alone and in synergy with IL-18 inhibits osteoclast formation in vitro. J Immunol. 2001;166(8):4915–21. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.8.4915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamada N, Niwa S, Tsujimura T, Iwasaki T, Sugihara A, Futani H, et al. Interleukin-18 and interleukin-12 synergistically inhibit osteoclastic bone-resorbing activity. Bone. 2002;30(6):901–8. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(02)00722-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moreno ML, Crusius JB, Cherñavsky A, Sugai E, Sambuelli A, Vazquez H, et al. The IL-1 gene family and bone involvement in celiac disease. Immunogenetics. 2005;57(8):618–20. doi: 10.1007/s00251-005-0033-x. Epub 2005 Sep 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taranta A, Fortunati D, Longo M, Rucci N, Iacomino E, Aliberti F, et al. Imbalance of osteoclastogenesis-regulating factors in patients with celiac disease. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19(7):1112–21. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040319. Epub 2004 Mar 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smecuol E, Mauriño E, Vazquez H, Pedreira S, Niveloni S, Mazure R, et al. Gynaecological and obstetric disorders in coeliac disease: frequent clinical onset during pregnancy or the puerperium. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;8(1):63–89. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199601000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ludvigsson JF, Michaelsson K, Ekbom A, Montgomery SM. Coeliac disease and the risk of fractures—a general population-based cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25(3):273–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.West J, Logan RF, Card TR, Smith C, Hubbard R. Fracture risk in people with celiac disease: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2003;125(2):429–36. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00891-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olmos M, Antelo M, Vazquez H, Smecuol E, Mauriño E, Bai JC. Systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies on the prevalence of fractures in coeliac disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2008;40(1):46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.09.006. Epub 2007 Nov 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bai JC, Gonzalez D, Mautalen C, Mazure R, Pedreira S, Vazquez H, et al. Long-term effect of gluten restriction on bone mineral density of patients with coeliac disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11(1):157–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.112283000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McFarlane XA, Bhalla AK, Robertson DA. Effect of a gluten free diet on osteopenia in adults with newly diagnosed coeliac disease. Gut. 1996;39(2):180–4. doi: 10.1136/gut.39.2.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sategna-Guidetti C, Grosso SB, Grosso S, Mengozzi G, Aimo G, Zaccaria T, et al. The effects of 1-year gluten withdrawal on bone mass, bone metabolism and nutritional status in newly-diagnosed adult coeliac disease patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14(1):35–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Valdimarsson T, Löfman O, Toss G, Ström M. Reversal of osteopenia with diet in adult coeliac disease. Gut. 1996;38(3):322–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.3.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moreno ML, Vazquez H, Mazure R, Smecuol E, Niveloni S, Pedreira S, et al. Stratification of bone fracture risk in patients with celiac disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2(2):127–34. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(03)00320-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination The periodic health examination [Bibliography] CMAJ. 1979;121(9):1193–254. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rostom A, Dubé C, Cranney A, Saloojee N, Sy R, Garritty C, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of serologic tests for celiac disease: a systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(4 Suppl 1):S38–46. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hopper AD, Cross SS, Hurlstone DP, McAlindon ME, Lobo AJ, Hadjivassiliou M, et al. Pre-endoscopy serological testing for coeliac disease: evaluation of a clinical decision tool. BMJ. 2007;334(7598):729. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39133.668681.BE. Epub 2007 Mar 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Villalta D, Alessio MG, Tampoia M, Tonutti E, Brusca I, Bagnasco M, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of IgA anti-tissue transglutaminase antibody assays in celiac disease patients with selective IgA deficiency. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1109:212–20. doi: 10.1196/annals.1398.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Villalta D, Alessio MG, Tampoia M, Tonutti E, Brusca I, Bagnasco M, et al. Testing for IgG class antibodies in celiac disease patients with selective IgA deficiency. A comparison of the diagnostic accuracy of 9 IgG anti-tissue transglutaminase, 1 IgG anti-gliadin and 1 IgG anti-deaminated gliadin peptide antibody assays. Clin Chim Acta. 2007;382(1–2):95–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2007.03.028. Epub 2007 Apr 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.James SP. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement on Celiac Disease, June 28–30, 2004. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(4 Suppl 1):S1–S9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rostami K, Kerckhaert J, Tiemessen R, von Blomberg BM, Meijer JW, Mulder CJ. Sensitivity of antiendomysium and antigliadin antibodies in untreated celiac disease: disappointing in clinical practice. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(4):888–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.983_f.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buchman AL. Population-based screening for celiac disease: improvement in morbidity and mortality from osteoporosis? Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(4):370–2. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.4.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bonamico M, Mariani P, Thanasi E, Ferri M, Nenna R, Tiberti C, et al. Patchy villous atrophy of the duodenum in childhood celiac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;38(2):204–7. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200402000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ravelli A, Bolognini S, Gambarotti M, Villanacci V. Variability of histologic lesions in relation to biopsy site in gluten-sensitive enteropathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(1):177–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaukinen K, Partanen J, Mäki M, Collin P. HLA-DQ typing in the diagnosis of celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(3):695–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Collin P. Should adults be screened for celiac disease? What are the benefits and harms of screening? Gastroenterology. 2005;128(4 Suppl 1):S104–8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mearin ML, Ivarsson A, Dickey W. Coeliac disease: is it time for mass screening? Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19(3):441–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Catassi C, Kryszak D, Louis-Jacques O, Duerksen DR, Hill I, Crowe SE, et al. Detection of celiac disease in primary care: a multicenter case-finding study in North America. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(7):1454–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01173.x. Epub 2007 Mar 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Drummond FJ, Annis P, O’Sullivan K, Wynne F, Daly M, Shanahan F, et al. Screening for asymptomatic celiac disease among patients referred for bone densitometry measurement. Bone. 2003;33(6):970–4. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.González D, Sugai E, Gomez JC, Oliveri MB, Gomez Acotto C, Vega E, et al. Is it necessary to screen for celiac disease in postmenopausal osteoporotic women? Calcif Tissue Int. 2002;71(2):141–4. doi: 10.1007/s00223-001-1027-9. Epub 2002 Jul 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lindh E, Ljunghall S, Larsson K, Lavö B. Screening for antibodies against gliadin in patients with osteoporosis. J Intern Med. 1992;231(4):403–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1992.tb00951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mather KJ, Meddings JB, Beck PL, Scott RB, Hanley DA. Prevalence of IgA-antiendomysial antibody in asymptomatic low bone mineral density. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(1):120–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nuti R, Martini G, Valenti R, Giovani S, Salvadori S, Avanzati A. Prevalence of undiagnosed coeliac syndrome in osteoporotic women. J Intern Med. 2001;250(4):361–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2001.00895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sanders DS, Patel D, Khan FB, Westbrook RH, Webber CV, Milford-Ward A, et al. Case-finding for adult celiac disease in patients with reduced bone mineral density. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50(3):587–92. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-2479-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stenson WF, Newberry R, Lorenz R, Baldus C, Civitelli R. Increased prevalence of celiac disease and need for routine screening among patients with osteoporosis. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(4):393–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.4.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Karakan T, Ozyemisci-Taskiran O, Gunendi Z, Atalay F, Tuncer C. Prevalence of IgA-antiendomysial antibody in a patient cohort with idiopathic low bone mineral density. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(21):2978–82. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i21.2978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Betterle C, Dal Pra C, Mantero F, Zanchetta R. Autoimmune adrenal insufficiency and autoimmune polyendocrine syndromes: autoantibodies, autoantigens, and their applicability in diagnosis and disease prediction. Endocr Rev. 2002;23(3):327–64. doi: 10.1210/edrv.23.3.0466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Betterle C, Lazzarotto F, Spadaccino AC, Basso D, Plebani M, Pedini B, et al. Celiac disease in North Italian patients with autoimmune Addison’s disease. Eur J Endocrinol. 2006;154(2):275–9. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Myhre AG, Aarsetøy H, Undlien DE, Hovdenak N, Aksnes L, Husebye ES. High frequency of coeliac disease among patients with autoimmune adrenocortical failure. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38(5):511–5. doi: 10.1080/00365520310002544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bushara KO. Neurologic presentation of celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(4 Suppl 1):S92–7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jokinen J, Peters U, Mäki M, Miettinen A, Collin P. Celiac sprue in patients with chronic oral mucosal symptoms. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1998;26(1):23–6. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199801000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Corazza GR, Andreani ML, Venturo N, Bernardi M, Tosti A, Gasbarrini G. Celiac disease and alopecia areata: report of a new association. Gastroenterology. 1995;109(4):1333–7. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90597-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fessatou S, Kostaki M, Karpathios T. Coeliac disease and alopecia areata in childhood. J Paediatr Child Health. 2003;39(2):152–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2003.00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rostami K, Kerckhaert J, Tiemessen R, Meijer JW, Mulder CJ. The relationship between anti-endomysium antibodies and villous atrophy in coeliac disease using both monkey and human substrate. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11(4):439–42. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199904000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tursi A, Brandimarte G, Giorgetti GM. Sorbitol H2-breath test versus anti-endomysium antibodies for the diagnosis of subclinical/silent coeliac disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36(11):1170–2. doi: 10.1080/00365520152584798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tursi A, Brandimarte G, Giorgetti GM. Prevalence of antitissue transglutaminase antibodies in different degrees of intestinal damage in celiac disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36(3):219–21. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200303000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.AGA Institute AGA Institute Medical Position Statement on the Diagnosis and Management of Celiac Disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(6):1977–80. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hill PG, Forsyth JM, Semeraro D, Holmes GK. IgA antibodies to human tissue transglutaminase: audit of routine practice confirms high diagnostic accuracy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004;39(11):1078–82. doi: 10.1080/00365520410008051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Armstrong D, Don-Wauchope AC, Verdu EF. Testing for gluten-related disorders in clinical practice: the role of serology in managing the spectrum of gluten sensitivity. Can J Gastroenterol. 2011;25(4):193–7. doi: 10.1155/2011/642452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dickey W, Kearney N. Overweight in celiac disease: prevalence, clinical characteristics, and effects of a gluten-free diet. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(10):2356–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]