Abstract

Background and aim

It is important to find economical methods in early Phase 2 studies to screen drugs potentially useful to aid smoking cessation. A method has been developed that detects efficacy of varenicline and nicotine patch. This study aimed to evaluate whether the method would detect efficacy of bupropion and correctly identify lack of efficacy of modafinil.

Design

Using a within-subject double crossover design, smokers attempted to quit during each treatment, with bupropion (150 mg b.i.d.), modafinil (100 mg b.i.d.), or placebo (double-blind, counter-balanced order). In each of three medication periods, all smoked with no drug on week 1 (baseline or washout), began dose run-up on week 2, and tried to quit every day during week 3.

Setting

A university research center in the United States.

Participants

Forty-five adult smokers high in quit interest.

Measurements

Abstinence was verified daily each quit week by self-report of no smoking over the prior 24 hr and CO<5 ppm.

Findings

Compared with placebo, bupropion did (F(1,44)=6.98, p=.01), but modafinil did not (F(1,44)=.29, p=.60), increase the number of abstinent days. Also, bupropion (versus placebo) significantly increased the number of those able to maintain continuous abstinence on all 5 days throughout the quit week (11 vs 4), Z= 2.11, p <.05, while modafinil did not (6).

Conclusions

Assessing days abstinent during 1 week of use of medication versus placebo in a cross-over design could be a useful early Phase 2 study design for discriminating between medications useful vs not useful in aiding smoking cessation.

INTRODUCTION

Of the few dozen drugs tested for smoking cessation in clinical trials over recent decades, few have shown efficacy (1–3), and only three have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as first-line treatments (nicotine replacement, varenicline, bupropion), highlighting the inefficiency of cessation medication development (4). Clinical trials that “fail” (i.e. show no efficacy) constitute unproductive uses of resources that would be better spent on more promising candidate drugs (5–6).

Our recent research program has aimed to improve the efficiency of an early cessation medication screening approach (i.e. early Phase 2) that optimally combines the validity of clinical trials with the practicality of lab-based studies (7–8). Here, improved “efficiency” is defined as obtaining a reliable and valid yes or no answer as to the likely clinical efficacy of a medication using a smaller subject sample and/or a shorter duration of testing (9). The overall objective is to determine whether a novel medication does, or does not, show sufficient promise of efficacy to justify the time and expense of conducting a randomized Phase 2 clinical trial of the medication for cessation in smokers making a permanent quit attempt (6). Specifically, our procedure tests smokers with a high interest in quitting soon in a within-subject, crossover design comparing duration of short-term smoking abstinence on active medication versus placebo (10–11). Because testing is of medications for smoking abstinence, rather than harm reduction, our procedure focuses on assessing the most valid outcome for 24-hr abstinence, biochemically-verified expired-air carbon monoxide level (CO), and not outcomes less directly related such as reduced cigarettes per day (see 7). Our approach enhances statistical power because all participants receive both medication conditions, eliminating most individual variability (12–13). We have demonstrated the sensitivity of this approach, i.e. ability to identify efficacy in a truly effective abstinence medication, using as model drugs the FDA-approved cessation medications of nicotine replacement (via patch) and varenicline (10–11).

The current study had two primary aims. First, we wanted to provide a further test of the procedure’s sensitivity with bupropion (300 mg/day), the only other FDA-approved first-line cessation medication. Bupropion has been widely shown to be efficacious for quitting smoking (e.g. 14). Our second aim was to assess the specificity of this approach, its ability to detect failure of a novel medication that is truly ineffective for quitting, using modafinil as a model drug. Modafinil (200 mg/day) is FDA-approved for wakefulness but has been shown to be ineffective for smoking cessation (15) as well as for acute nicotine withdrawal relief (15–16). Specificity of a medication screening procedure is as important as its sensitivity because an efficient procedure must also be able to determine whether a novel compound does not warrant further evaluation with larger randomized clinical trials. All participants were smokers wanting to quit smoking soon (i.e. within 3 months, after the study). All made a brief attempt at quitting for one week with each of three medication conditions—bupropion, modafinil, and placebo—in a double crossover design.

METHODS

Study Participants

To recruit those with high current “intrinsic” quit interest, we sought smokers who already intended to quit permanently “soon”. The study was described in recruitment notices as an evaluation of the short-term effects of bupropion and modafinil on smoking behavior, craving, and mood, but also as “not a treatment study.” Prospective participants were briefly screened by telephone and then again in person for smoking history, health, and intention to quit permanently. Eligible subjects were required to be aged 18–65, smoke at least 10 cigarettes per day for at least 1 year, provide a mid-day screening CO reading of at least 10 ppm, and to not currently be in the process of quitting. Current intrinsic quit interest was assessed by asking subjects whether or not they intended to quit in the next 3 months, 6 months, or 1 year, with each time frame asked separately. Those stating an intention to quit in the next 3 months were labeled “high” in current quit interest, while those intending to quit no sooner than the next 6 months or later were excluded from participation. As in our prior study with varenicline (11), we also offered free open-label cessation treatment with bupropion and brief counseling after completing the study, to further attract participation by smokers with high quit interest. Those wanting only to quit immediately were referred to treatment programs elsewhere and not included in the study, due to the need for smoking resumption between cross-over medication conditions (see protocol, below). To be eligible for the study, participants had to give the same response to this measure both during phone screening and subsequent in-person screening to demonstrate reliable quit interest. All also agreed in writing that they would try hard to quit during the quit assessment weeks (weeks 3, 6, and 9). Subjects were then given a physical exam by physician to confirm eligibility. This study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Medications

Bupropion XL (ZybanR) and modafinil (ProvigilR) were obtained by the University of Pittsburgh Investigational Drug Service and encapsulated to maintain double-blind procedures. Placebo (dextrose) capsules matched in size and appearance were also provided. The bupropion XL dose run-up regimen was that recommended clinically for those quitting smoking, 150 mg qd for 3 days followed by the full dose of 150 mg b.i.d. (i.e. 300 mg/day). Modafinil similarly involved 100 mg qd for 3 days followed by the full dose of 100 mg b.i.d. (200 mg/day). These doses of bupropion and modafinil were selected based on prior research showing efficacy and no efficacy, respectively, of these medications for smoking cessation (14, 15), supporting their use here to assess our early Phase 2 procedure’s sensitivity for showing cessation efficacy in bupropion and specificity for detecting no efficacy in modafinil. The same number of placebo capsules was taken during the weeks of the placebo condition. Compliance during run-up and quit weeks (weeks 2 and 3 of each phase) was 99% for each medication condition (including placebo), assessed by pill counts at every visit. Open label bupropion SR was obtained in the same fashion for the optional post-study quit attempt, but it was administered in tablet form and not encapsulated.

Assessment of days abstinent

During the quit week of each medication condition, abstinence was assessed daily by self-report of no smoking at all over the prior 24 hrs and an expired-air carbon monoxide (CO) <5 ppm. This stringent biochemical criterion for validating smoking cessation has been shown to be more sensitive and specific than traditional (higher) CO cut-offs. (17–18). Every day that subjects met these abstinence criteria, $12 was added to the participation compensation per visit to maintain quit motivation (19).

Self-report measures

Craving and withdrawal were assessed at every visit by the Questionnaire of Smoking Urges-brief (QSU) (20) and the Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale (MNWS) (21), respectively, with each item scored on a 0–100 visual analog scale (VAS). After the dose run-up week, medication blinding was assessed on Monday of the quit week, as subjects chose from among four response options--“Bupropion (Zyban)”, “Modafinil (Provigil)”, “Placebo (no medication)”, or “don’t know”--to indicate what they perceived to be the contents of the capsule they were taking. Side effects were rated on a 0 to 3 scale (none, mild, moderate, severe) and included nausea, agitation, nervousness, constipation, dry mouth, fatigue, insomnia, headache, increased appetite, decreased appetite, etc.

Experimental protocol

Except for comparisons of two active drugs with placebo, most procedures were the same as those described in our prior placebo-controlled trials with nicotine patch (10) and with varenicline (11). This study was a three condition, cross-over design, with one within-subjects factor of medication: bupropion (150 mg b.i.d.), modafinil (100 mg b.i.d.), and placebo. Study participation for each subject was 9 weeks, consisting of three 3-week phases. Each phase involved a week of ad libitum smoking with no medication (baseline, week 1), followed by a week of starting the medication regimen while continuing to smoke (dose run-up, week 2), and then a week of trying to abstain Mon-Fri while using active or placebo (quit assessment, week 3). The next medication phase began a week following completion of the prior phase, starting with ad lib smoking and no medication (i.e. washout). Thus, subjects who abstained during the quit week of one condition had to resume smoking during the baseline week for the next medication condition. (Subjects who quit were told they did not have to resume smoking if they wanted to remain abstinent, although they would not be able to continue in the study. Only one participant failed to resume smoking after quitting during the first study phase and was excluded from analyses.) Order of bupropion, modafinil, and placebo across the 3 phases was counter-balanced between subjects (6 possible orders, randomly assigned). Participants came to the clinic for brief assessment visits on 3 days per week during each baseline and dose run-up week (e.g. Tues, Thurs, Fri) and all 5 weekdays (Mon-Fri) during each quit week. Daily assessments included CO, withdrawal, and craving. They were compensated for their time at $20 for each visit. During the screening session prior to study entry, subjects provided written informed consent for participation after the nature and consequences of the study were explained.

Data Analyses

Preliminary ANOVAs using IBM SPSS 20.0 examined the effects of sex and of medication order between phases. No significant effects of either were found. The primary analysis was a repeated-measures ANOVA of days of abstinence per quit assessment week (range of 0–5, not necessarily consecutive), with medication (bupropion, modafinil, placebo) as the within-subjects factor. Comparisons of each active medication condition with the placebo condition were emphasized. We also used nonparametric tests to determine the effects of bupropion, or of modafinil, versus placebo (Wilcoxon signed ranks) on continuous abstinence throughout the week (i.e. quit on all 5 days), and on ability to avoid relapse during the quit week if abstinence was initiated (i.e. no relapse at any point before the end of the week), as well as on side effects. In analyses of craving and withdrawal, we used repeated measures linear mixed effects models with residual maximum likelihood (REML) estimation to determine effects of medication condition. Only data from abstinent days were included, to avoid confounding medication effects with relief from continuing to smoke. All models assumed a compound symmetric covariance structure between repeated measurements.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

Mean (SD) sample characteristics for these 45 adult smokers (27 women, 18 men) were 36.1 (± 12.5) years of age, 15.8 (± 5.3) cigarettes smoked per day, Fagerstrom Test of Nicotine Dependence (FTND) (22) score of 4.6 (± 1.9), and they had made 2.3 (± 1.9) prior attempts to quit smoking. Participants were recruited from the surrounding community and most self-identified as Caucasian (77.8%), with 4.4% African-American, 6.7% Asian, 8.9% as more than one ethnicity, and 2.2% who did not self-identify. There were no significant differences between women and men in any of these characteristics. We excluded those reporting current major health problems (e.g. heart disease, diabetes) or taking medications to treat serious psychological problems (e.g. psychosis, major depression). Two others, both women, discontinued participation due to complaints about adverse effects during the modafinil phase, one for anxiousness and one for blurry vision.

PRIMARY OUTCOMES

Number of Abstinent Days

Comparison of bupropion versus placebo tested the sensitivity of our procedure, while comparison of modafinil versus placebo examined the procedure’s specificity. The mean (SE) numbers of abstinent days out of five during the weeks (Mon-Fri) of attempting to quit on bupropion or modafinil, versus placebo, are shown in Figure 1. In the primary analysis of variance (ANOVA) of this fully within-subjects design, significant main effects on days abstinent were seen for overall medication condition, F(2,88)=3.40, p=.04. In planned contrasts, compared to placebo (1.58±0.26), bupropion did (2.24±0.31, F(1,44)=6.98, p=.01), but modafinil did not (1.71±0.28, F(1,44)=.29, p=.60), increase the number of abstinent days during the 5-day quit period for each medication. In a secondary comparison, bupropion also tended to increase days abstinent more than modafinil, F(1,44)=3.04, p=.09. Other analyses showed no influence on days of abstinence due to either the main effect of medication order, F(5, 39)<1, ns, or the interaction of order × medication condition, F(10,78)<1, ns.

Figure 1.

Mean (±SEM) days abstinent (left) and proportion able to achieve full continuous 5-day abstinence (right) during each quit week due to placebo, modafinil (100 mg b.i.d.), and bupropion (150 mg b.i.d.). All 45 subjects were included in each dependent measure in this within-subjects cross-over design. * p<.05 and ** p=.01 for significance between medication conditions.

Continuous 5-day Quit

Similarly, as also shown in Figure 1, bupropion (versus placebo) significantly increased the number of subjects, out of the total sample of 45, able to maintain continuous abstinence on all 5 days throughout the quit week, 11 vs. 4 (24.4% vs 8.9%), respectively, Wilcoxon Z= 2.11, p <.05. Moreover, with bupropion, 14 of the 31 who initiated quitting during the week (even if after the first few days) were able to avoid relapse (45.2%), compared to 5 of the 26 initiating quit on placebo (19.2%), also Z= 2.11, p <.05 (not shown). Consistent with the analyses of days abstinent, modafinil had no significant differences with placebo on either of these quit outcomes (6, or 13.3%, for continuous abstinence, and 6 of 27, or 22.2%, for avoid relapse if able to quit).

SECONDARY OUTCOMES

Other responses to bupropion and to modafinil were also compared separately with responses to the placebo condition, as we did not hypothesize any differences between the two active medication conditions.

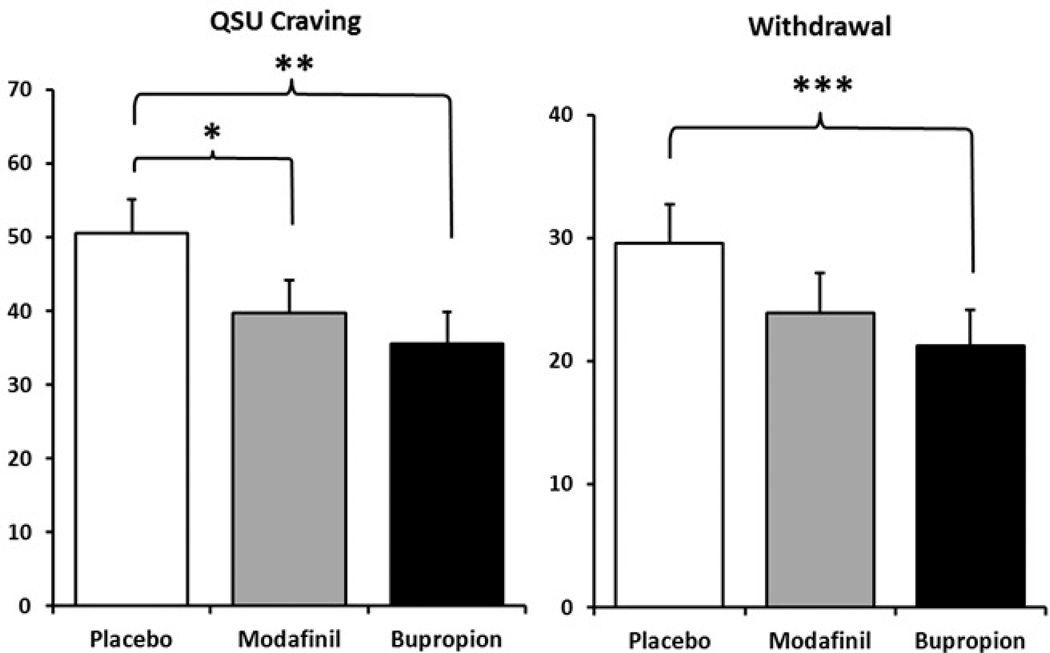

Craving and withdrawal

Because exposure to nicotine via smoking would confound responses to medication condition, analyses of craving and withdrawal were limited to only responses from abstinent days. Compared to placebo, bupropion and modafinil each decreased QSU craving (17), F (1, 24)’s of 10.22, p<.005, and 4.77, p<.05, respectively, as shown in Figure 2, but only bupropion decreased overall MNWS (18) withdrawal, F(1, 22) =23.81, p<.001, while modafinil’s effect was not significant, F(1,22)=2.48, p>.10.

Figure 2.

Mean (±SEM) craving (QSU) and withdrawal (MNWS) scores due to placebo, modafinil, and bupropion. Data are only from days in which subjects were abstinent, to avoid confounding responses to medication with relief from continued smoking. * p<.05, ** p<.005, and *** p<.001 for significance from placebo. No other differences were significant.

Medication adverse effects

Adverse effects were mild, with most subjects responding “0” (none at all) for each effect during all three drug phases. Means for nearly all effects were 0.3 or below on the 0–3 scale. Bupropion and modafinil, relative to placebo, were each rated significantly lower on agitation (0.26 and 0.28, respectfully, vs 0.44) and higher on decreased appetite (both were 0.14, vs 0.02 for placebo), indicating relief of withdrawal and no actual “adverse” effects. As noted above, however, two others discontinued participation due to adverse effects on modafinil (self-reports of anxiousness or blurry vision).

Medication blinding

The respective number (percent) of subjects identifying the medication as bupropion, modafinil, placebo, or don’t know were 4, 2, 5, and 34 (8.9%, 4.4%, 11.1%, and 75.6%) out of 45 during the bupropion condition; 7, 3, 4, and 31 (15.6%, 6.7%, 8.9%, and 68.9%) out of 45 during the modafinil condition; and 4, 3, 8, and 30 (9.1%, 6.8%, 18.2%, and 67.9%) out of 44 (one subject with missing data) during the placebo condition. None of these values differed by medication condition, indicating successful blinding. We also found no difference in days of abstinence between those who did vs. did not correctly guess their medication condition, including during the quit week when receiving bupropion, 3.50±1.00 vs. 2.17±.31, respectively, F(1,43)=1.60, p=.21.

Validation of Quit Interest

After completing the study, as noted, all 45 subjects were offered free written cessation material and brief (10 min) cognitive-behavioral counseling (23), and they were instructed to set a quit date within two weeks. This free open-label bupropion and bi-weekly brief counseling sessions were offered for 12 weeks. Three weeks after the end of study participation, all subjects were contacted by phone and asked about their smoking since the end of the study, regardless of whether or not they set a target quit date. There was no incentive for how they responded, and they were given the following response options: did not quit or cut down, cut down but did not quit, or quit. For those saying they had quit, they were asked how long they had stayed quit. Only those reporting they had quit for at least 24 hr were viewed as having made a true post-study quit attempt. Generally consistent with their self-reported quit interest at study entry, 26 (58%) quit and 6 (13%) cut down or quit for less than 24 hr, while 11 (24%) could not be reached. Only 2 (4%) indicated no attempt to quit or cut down.

DISCUSSION

In this study, our innovative early Phase 2 procedure showed further sensitivity for identifying efficacy in smoking cessation medications by demonstrating greater days abstinent and continuous abstinence during the quit week with bupropion versus placebo, consistent with our prior cross-over studies comparing quit days on nicotine patch (10) and varenicline (11) with placebo. This procedure also displayed specificity for detecting no efficacy in ineffective cessation medications by showing no increase in days abstinent due to modafinil versus placebo. Therefore, our within-subjects cross-over procedure of assessing brief quit periods due to medication and placebo in smokers with high quit interest may be a more efficient method for testing initial evidence of cessation efficacy in novel medications.

The greater efficiency (9) of our model relative to formal randomized clinical trials is shown by two of its key features: 1) the relatively brief, 3-week duration of testing with each medication condition (including smoking baseline prior to dose run-up), and 2) the fact that fewer than 50 smokers were needed to show cessation efficacy in bupropion relative to placebo. These aspects of the procedure are very comparable to the duration and sample sizes used in our prior studies to demonstrate sensitivity of nicotine patch and varenicline effects in aiding cessation in smokers high in quit interest (10–11), those typically appropriate for Phase 2 clinical trials employing traditional randomized study designs. By contrast, an early Phase 2 test of initial medication efficacy in a randomized trial with the same statistical power to compare active and placebo conditions would require more than 100 smokers in each of the two medication conditions. This is due to the typically high within-subject correlation (i.e. rho) of days quit responses to active medication versus placebo, which in this study was r=.59, both for bupropion and for modafinil, greatly reducing the error variance between conditions. Consequently, the sample size for a two-armed randomized trial of similar power vs our crossover trial would be 2/(1−r) × the sample size for our within-S design (N=45), or 2/(1−.59) × 45, which (for this study) is 220 (8, 24).

Among other strengths of this study is the demonstrated feasibility of this cross-over design for early Phase 2 research with cessation drugs, in that we found no significant medication order effects, although we did with varenicline in our prior study with this design (11). Also, despite their high quit interest, all but one participant resumed smoking during the washout period between medication conditions to provide a comparable test of each medication on ability to aid cessation. Our secondary analyses showed the sensitivity of the procedure for assessing potential mechanisms of medication efficacy for cessation by the differences from placebo in craving and withdrawal on the quit days, although modafinil may modestly reduce craving even if it shows no efficacy for days abstinent or withdrawal.

Regarding limitations, we did not assess potential unauthorized use of nicotine replacement or other means to help quit, although any such use would be expected to occur during each quit week and so comparably influence days quit under all three medication conditions. Also, our procedure may have practical limitations for initial evaluations of efficacy in some novel compounds, such as those requiring a long dose run-up period or a long washout period, which would also be required for the placebo condition to maintain blinding. Comparing more than one active medication versus placebo, as in this study, would exacerbate these limitations. Compounds with clear psychoactive effects also may complicate attempts to keep participants blind to the condition being tested.

Our next step is to apply this procedure to screening novel medications for smoking cessation, in the hope of enhancing the efficiency by which drug development resources evaluate new compounds and improving the chances of success among compounds proceeding to formal late Phase 2 or Phase 3 clinical trials (7). The crossover design in the current study, with two active medications and placebo, could be employed to compare two active doses of a novel compound versus placebo. Also of future interest is examination of whether a similar procedure increases the sensitivity and specificity of short-term tests of novel compounds to treat other substance abuse problems, such as alcohol dependence (25). Positive findings could thereby increase the efficiency of initial screening of new medications for these drug dependencies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors also acknowledge the contributions of Paul Wileyto, PhD, Carolyn Fonte, RN, Melissa Mercincavage, BS, and Erin Stratton, BS during this study.

This research was supported by NIH Grant P50 CA143187. The sponsor of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. Dr. Perkins had full access to all the data and takes full responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Dr. Perkins has served as a consultant for Embera Neurotherapeutics that is unrelated to the current study. Dr. Lerman has served as a consultant for GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, and Astra Zeneca. She has received research funding, unrelated to the current study, from Pfizer and Astra Zeneca. Dr. Chengappa has research funding from Pfizer that is unrelated to the current study.

Footnotes

Dr. Sparks, Mr. Karelitz, and Ms. Jao have no potential conflicts of interest or disclosures to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benowitz NL, Peng MW. Non-nicotine pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation. CNS Drugs. 2000;13:265–285. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foulds J, Steinberg MB, Williams JM, Ziedonis D. Developments in pharmacotherapy for tobacco dependence: past, present and future. Drug Alc Rev. 2006;25:59–71. doi: 10.1080/09595230500459529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hughes JR, Goldstein MG, Hurt RD, Shiffman S. Recent advances in the pharmacotherapy of smoking. JAMA. 1999;281:72–76. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lerman C, LeSage MG, Perkins KA, O’Malley SS, Siegel SJ, Benowitz NL, Corrigall WA. Translational research in medication development for nicotine dependence. Nature Rev Drug Dev. 2007;6:746–762. doi: 10.1038/nrd2361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paul SM, Mytelka DS, Dunwiddie CT, Persinger CC, Munos BH, Lindborg SR, Schacht AL. How to improve R&D productivity: the pharmaceutical industry’s grand challenge. Nature Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:203–214. doi: 10.1038/nrd3078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kola I. The state of innovation in drug development. Clin Pharm Ther. 2008;83:227–230. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perkins KA, Stitzer M, Lerman C. Medication screening for smoking cessation: a proposal for new methodologies. Psychopharmacol. 2006;184:628–636. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perkins KA, Lerman C. Early human screening of medications to treat drug addiction: Novel paradigms and the relevance of pharmacogenetics. Clin. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89:460–463. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Streiner DL. Alternatives to placebo-controlled trials. Can J Neurol Sci. 2007;34(suppl 1):S37–S41. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100005540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perkins KA, Lerman C, Stitzer ML, Fonte CA, Briski JL, Scott JA, Chengappa KNR. Development of procedures for early human screening of smoking cessation medications. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84:216–221. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perkins KA, Lerman C, Fonte C, Mercincavage M, Stitzer ML, Chengappa KRN, Jain A. Cross-validation of a new procedure for early screening of smoking cessation medications in humans. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;88:109–114. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cleophas TJM. Cross-over studies: a modified analysis with more power. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1993;53:515–520. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1993.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hays JT, Ebbert JO. Bupropion for the treatment of tobacco dependence. CNS Drugs. 2003;17:71–83. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200317020-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schnoll RA, Wileyto EP, Pinto A, Leone F, Gariti P, Siegel S, et al. A placebocontrolled trial of modafinil for nicotine dependence. Drug Alc Depend. 2008;98:86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sofuoglu M, Waters AJ, Mooney M. Modafinil and nicotine interactions in abstinent smokers. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2008;23:21–30. doi: 10.1002/hup.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Javors MA, Hatch JP, Lamb RJ. Cut-off levels for breath carbon monoxide as a marker for cigarette smoking. Addiction. 2005;100:159–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perkins KA, Karelitz JL, Jao NC. Optimal carbon monoxide criteria to confirm 24-hr smoking abstinence. Nic Tob Res. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts205. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stitzer ML, Rand CS, Bigelow GE, Mead AM. Contingent payment procedures for smoking reduction and cessation. J Appl Beh Analysis. 1986;19:197–202. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1986.19-197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cox LS, Tiffany ST, Christen AG. Evaluation of the brief questionnaire of smoking urges (QSU-brief) in laboratory and clinical settings. Nic Tob Res. 2001;3:7–16. doi: 10.1080/14622200020032051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hughes JR, Gust SW, Skoog K, Keenan RM, Fenwick JW. Symptoms of tobacco withdrawal. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 1991;48:52–59. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810250054007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom K-O. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addiction. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perkins KA, Conklin CA, Levine MD. Cognitive-behavioral Therapy for Smoking Cessation: A Practical Guide to the Most Effective Treatments. New York: Routledge; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fleiss JL. The Design and Analysis of Clinical Experiments. New York: Wiley; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jupp B, Lawrence AJ. New horizons for therapeutics in drug and alcohol abuse. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;125:138–168. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]