Summary

The bacterial flagellin (FliC) epitopes flg22 and flgII-28 are microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs). While flg22 is recognized by many plant species via the pattern recognition receptor FLS2, neither the flgII-28 receptor nor the extent of flgII-28 recognition by different plant families is known.

Here we tested the significance of flgII-28 as a MAMP and the importance of allelic diversity in flg22 and flgII-28 in plant–pathogen interactions using purified peptides and a Pseudomonas syringae ΔfliC mutant complemented with different fliC alleles.

Plant genotype and allelic diversity in flg22 and flgII-28 were found to significantly affect the plant immune response but not bacterial motility. Recognition of flgII-28 is restricted to a number of Solanaceous species. While the flgII-28 peptide does not trigger any immune response in Arabidopsis, mutations in both flg22 and flgII-28 have FLS2-dependent effects on virulence. However, expression of a tomato allele of FLS2 does not confer to Nicotiana benthamiana the ability to detect flgII-28 and tomato plants silenced for FLS2 are not altered in flgII-28 recognition.

Therefore, MAMP diversification is an effective pathogen virulence strategy and flgII-28 appears to be perceived by a yet unidentified receptor in the Solanaceae although it has an FLS2-dependent virulence effect in Arabidopsis.

Keywords: flagellin, flg22, flgII-28, FLS2, microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMP), pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMP), pattern-triggered immunity (PTI)

Introduction

Perception of conserved molecular patterns of microbes, called PAMPs (pathogen-associated molecular patterns) or MAMPs (microbe-associated molecular patterns), is an important first line of plant defense known as pattern-triggered immunity (PTI) (Jones & Dangl, 2006; Segonzac & Zipfel, 2011). Perception of the 22-amino acid flagellin epitope flg22 is one of the most studied examples of PTI. The flg22 epitope directly binds to the pattern recognition receptor (PRR) FLS2 (Chinchilla et al., 2006), after which FLS2 interacts with the adaptor protein BAK1 (Chinchilla et al., 2007b; Heese et al., 2007) and several other receptor-like kinases (RLKs) (Roux & Zipfel, 2012). These interactions lead to the rapid efflux of Ca2+ and activation of calcium-dependent protein kinases (CDPKs)(Boudsocq et al., 2010), generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Felix et al., 1999) and activation of MAP kinase cascades (Rasmussen et al., 2012) triggering a complex defense response which includes FLS2-dependent stomatal closure to interfere with pathogen invasion (Melotto et al., 2006; Zeng & He, 2010), callose deposition to strengthen plant cell walls (Gomez-Gomez & Boller, 2000), and induction of pathogenesis-related genes to restrict pathogen growth (Gómez-Gómez et al., 1999; Chinchilla et al., 2007a). Pre-treatment of Arabidopsis plants with flg22 epitope before pathogen inoculation decreases pathogen growth while fls2 mutant plants are more susceptible to Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato (Pto) infection following spray inoculation (Zipfel et al., 2004) demonstrating that flg22 recognition by FLS2 has biological relevance. Interestingly, flagellin recognition evolved in parallel in plants and animals (Ausubel, 2005; Zipfel & Felix, 2005). In mammals, the PRR TLR5 recognizes extracellular flagellin (Hayashi et al., 2001) and the intracellular receptor NLRC4 recognizes flagellin inside macrophages (Kofoed & Vance, 2011; Zhao et al., 2011).

An important strategy of plant pathogens to avoid PTI is injection of immunity-suppressing effector proteins directly into host cells (Chisholm et al., 2006; Jones & Dangl, 2006; Cunnac et al., 2011). This strategy is best exemplified by the molecular mechanisms of the type III-secreted effector proteins AvrPto and AvrPtoB of Pto, both of which suppress FLS2-mediated immunity (Shan et al., 2008; Xiang et al., 2008; Cheng et al., 2011; Martin, 2012). Since MAMP-containing proteins and other molecules are by definition essential for a pathogen’s life cycle and/or pathogenicity (Jones & Dangl, 2006; Segonzac & Zipfel, 2011), pathogens cannot avoid PTI by losing essential proteins containing MAMPs and allelic variation of MAMPs is expected to be limited by evolutionary constraints on their structure (Bittel & Robatzek, 2007; Boller & Felix, 2009; McCann et al., 2012). Nonetheless, a few studies suggest that some pathogens are able to alter MAMPs to avoid PTI. For example, a single amino acid change in flg22 of the plant pathogen Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris severely attenuated or eliminated perception of flg22 by FLS2 (Sun et al., 2006); however, the mutation had no effect on pathogen growth during infection. Furthermore, no known alleles of flagellin from Ralstonia solanacearum elicit PTI (Pfund et al., 2004), but the effect of the evasion of flagellin recognition on pathogen growth during infection is not known. Also, post-translational modifications of flagellin, including glycosylation, can have a major impact on the elicitation activity of flagellin (Taguchi et al., 2003; Takeuchi et al., 2003). Flagellin proteins from the human pathogens Bartonella bacilliformi, Campylobacter jejuni, and Helicobacter pylori escape detection by TLR5 through mutations of amino acids in the known interaction surface (Andersen-Nissen et al., 2005). Diversity of flagellin perception due to allelic variation in FLS2 has also been demonstrated in that the flg15 epitope of Escherichia coli flagellin is recognized by tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) but not by Arabidopsis or Nicotiana benthamiana (Bauer et al., 2001; Meindl et al., 2000).

We previously determined that a second epitope of flagellin, termed flgII-28, is sufficient to trigger immunity in tomato (Cai et al., 2011). The flgII-28 epitope was identified based on two non-synonymous mutations in almost identical strains of the bacterial speck disease pathogen Pto, which suggested selection for evasion of flgII-28 perception by tomato. In fact, the two derived alleles of flgII-28 (flgII-28K40 and flgII-28Col338), which are present in Pto strains typical of recent bacterial speck disease outbreaks, trigger a weaker immune response in tomato cultivar cv ‘Chico III’ than the ancestral flgII-28T1 allele, which was the predominant allele of Pto strains that caused disease outbreaks before 1980 (Cai et al., 2011). Some Pto strains also have a mutation in flg22 but this mutation does not significantly affect the strength of the tomato immune response (Cai et al., 2011).

Here we find that there is significant variation both in the strength of PTI elicited by different flagellin proteins in the same plant and in perception of the same flagellin among different plants. Importantly, we show a significant effect of allelic variation in flg22 and flgII-28 on the outcome of plant–pathogen interaction in the absence of any effects on bacterial motility, thus revealing that allelic variation in MAMPs is an important PTI-avoidance mechanism in the evolutionary arms race between P. syringae pathogens and plants. Intriguingly, the effect of allelic variation in flgII-28 on bacterial growth on Arabidopsis is FLS2-dependent although recognition of the flgII-28 peptide appears to be FLS2-independent based on multiple lines of evidence. This suggests that flgII-28 may indirectly modulate flg22 perception by FLS2 and that Solanaceous plants are likely equipped with a second flagellin receptor that recognizes flgII-28.

Materials and Methods

Peptide synthesis and storage

Peptides were synthesized to 70–90% purity by EZ Biolab (Carmel, IN, USA) with the exception of the flg22 consensus peptide (QRLSTGSRINSAKDDAAGLQIA) used in Figs 4(d) and Supporting Information S6 which was synthesized by Biomatik (Cambridge, Ontario, Canada). Water was added to the peptides to bring them to a concentration of 5 μM except for the flgII-28 peptides which were insoluble in water (for some alleles) and were instead initially dissolved in a solution of 50% DMSO and diluted further in water. Dissolution in DMSO is unlikely to affect the ROS elicitation potential of the peptides because flgII-28T1 is an equivalent elicitor on S. lycopersicum whether dissolved in water or 50% DMSO (not shown). To maintain activity, peptides were stored in small aliquots to avoid multiple freezing and thawing. All dilutions to obtain working concentrations were done in ultrapure H2O. Peptide solutions were stored at −20°C for short-term usage or −80°C for long-term storage.

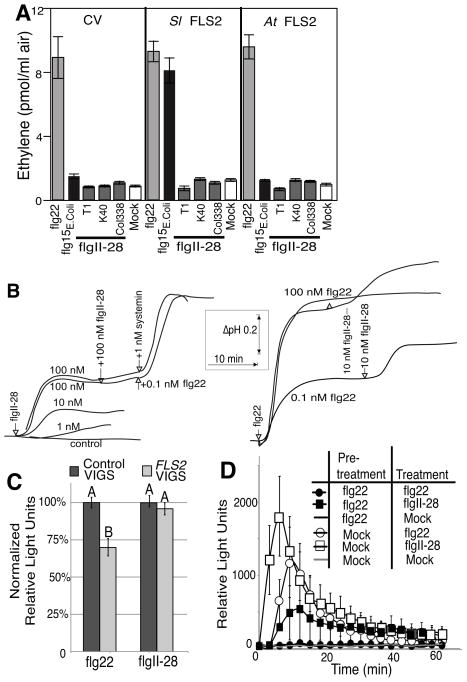

Fig. 4.

Tomato FLS2 is not sufficient for perception of flgII-28T1. (a)Transient expression of FLS2 in Nicotiana benthamiana does not lead to the detection of flgII-28T1. Leaf punches from leaves agrotransformed with control vector (CV), tomato FLS2 (Sl FLS2) and Arabidopsis FLS2 (At FLS2) were treated with indicated peptides at 1μM concentration and total ethylene production was measured 3.5 h after treatment. Data shown are the average of 6 replicates; error bars represent ± SE. (b) Alkalinization of extracellular pH in cell cultures derived from the wild tomato species peruvianum to treatment with the peptides flgII-28T1, flg22, and systemin. (c) The oxidative burst triggered by 10nM flg22 (grey bars) or 10nM flgII-28T1 (white bars) was quantified in S. lycopersicum cv ‘Rio Grande’ silenced for the flagellin receptor FLS2 (n=48; 6 experiments) or the flagellin co-receptor Bak1 (n=18; 3 experiments) compared to non-silenced control plants (n=48; 6 experiments). Total reactive oxygen species (ROS) production was measured over a 45 min time period, and the average of 3–4 leaf disks per plant was calculated. Bar values represent the normalized mean and the error bars ± SE. The statistical significance between silenced and control plants for each peptide treatment was assessed using Student’s t-test with the alpha level 0.005. (d) Leaf punches of 4-wk-old tomato cv ‘Rio Grande’ were treated with either 1μM of flg22 or H2O (mock) as indicated and then 50 min later treated with indicated peptides and ROS was measured for 1 h immediately following treatment. Similar results were obtained in 4 independent experiments. Data shown are the average of 6 replicate leaves.

Measurement of ROS generation

Previously described protocols were used to quantify production of ROS generation following elicitation with peptides (Chakravarthy et al., 2010). Briefly, leaf disks of 4-wk-old plants (except eggplant and bean for which 6-wk-old and 3-wk-old plants, respectively, were used) were punched out with a #1 cork borer and floated adaxial side up overnight at room temperature in 200μl ddH2O in individual wells of a clear-bottom 96 well microassay plate (Greiner Bio-one, Germany). 16 h later, the water was replaced with a solution containing 1μM peptide (unless concentration otherwise noted in figure), 34 μg ml−1 luminol, and 20μg ml−1 horseradish peroxidase (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) all in ddH2O. Luminescence of each well was then immediately measured using a Synergy HT plate reader (Biotek, Winooski, VT, USA) using the bottom camera at optical sensitivity of 225 every 3 min for 60 min. For comparison among different peptides, multiple leaf punches were taken from the same leaf to allow for the peptides to act on the same leaf (though different sections) to control for variability among leaves. 6 to 8 leaves were used for each experiment.

The following plants were screened via the ROS assay in this work: Arabidopsis thaliana ecos. ‘Columbia-0’, ‘Cvi-0’, and ‘WS’ (TAIR, Stanford, CA, USA); Radish cv ‘Champion’ (Ferry Morse, Futon, KY, USA); Turnip cv ‘Purple Top White Globe’ (Ferry Morse, Futon, KY); Cauliflower cv ‘Toscana 2 (Ferry Morse, Futon, KY)’; Snapdragon cv ‘Cook’s Tall’ (Cooks Garden, Warminster, PA, USA); Morning glory (Ferry Morse, Futon, KY, USA); Celery cv ‘S. V. Pascal’ (Seeds of Italy, Harrow, UK); Bean cv ‘Red Mexican’ (Vermont Bean Seed Company, Randolph, WI, USA); Tomato cvs. ‘Rio Grande’, ‘Chico III’, ‘Sunpride’ (Bavicchi, Ponte San Giovani, Italy) and ‘Roter Gnom’ (Canadian plant genetic resource center, Ottowa, Canada); Pepper cvs. ‘California Wonder’ (Wyatt-Quarles Seed, Garner, NC, USA) and ‘Jalapeno Early’ (Burpee, Warminster, PA, USA); Eggplant cv ‘MM643’ (INRA, Avignon, France); Nicotiana benthamiana, N. tabacum cv ‘Burly’ (personal lab stocks), and Potato cv ‘Red Maria’ (Maine Potato Lady, Guilford, ME, USA).

Measurement of ethylene production following peptide treatment

Fully expanded leaves of 4–6-wk-old Solanum lycopersicum cv ‘MoneyMaker’ (Thompson & Morgan, Ipswich, UK) and N. benthamiana, both grown in long day conditions (14 h photoperiod, 25°C), were cut into 2 mm slices and floated on water overnight. Leaf slices were transferred to 6ml glass tubes containing 0.5ml of an aqueous solution of the peptide being tested. Vials were closed with rubber septa and ethylene accumulating in the free air space was measured by gas chromatography after 3.5–4 h incubation.

Bayesian analysis of ROS assays

For analysis of ROS production, we modeled the data for each plant–peptide combination using a shifted Gompertz-decay curve (Eqn 4 in Methods S1). Estimation of the unknown modeling parameters was performed using a Markov Chain Monte Carlo algorithm. To initially address whether ROS is elicited by a plant-peptide combination, we calculated the posterior probability of the null hypothesis (no ROS response) given the data. That is, we fit the data to the Gompertz-decay with the parameters Θ1=Θ2=0 – a function of a flat line with no slope – and determined the posterior probability of this fit. To compare the ROS elicited by different peptides on the same plant, we determined Bayesian credible intervals of differences between peptides on each plant for 5 parameters describing the kinetics of ROS production: peak intensity, offset, increase rate, change point, and decrease rate (Fig. S1). See Methods S1 for more details.

Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression

For transient expression in N. benthamiana, A. tumefaciens harboring FLS2p::FLS2-3xmyc-GFP (Robatzek et al., 2006) and FLS2p::SlFLS2-GFP (Robatzek et al., 2007) in pCAMBIA2300 and the empty vector were grown overnight in YEB medium. Bacteria diluted in infiltration medium (10 mM MES, pH 5.6, 10 mM MgCl2) were pressure-infiltrated into leaves of 3–4-wk-old N. benthamiana plants. Leaves were assayed for ethylene biosynthesis 2 d after infiltration.

pH shift in S. peruvianum cell cultures

Cell cultures of S. peruvianum (Nover et al., 1982), formerly Lycopersicon peruvianum, were used as described previously (Meindl et al., 1998). Briefly, peptides were introduced into aliquots of 5–8 d old cell suspensions on a rotary shaker at 120rpm. Immediately following, the pH was measured with a glass electrode pH meter and recorded using a pen recorder. The plant wound hormone systemin (Meindl et al., 1998) was used as a positive control for cell culture alkalinization.

Virus induced gene silencing of FLS2

Virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) was performed using the tobacco rattle virus (TRV) system described in (Liu et al., 2002). Mixtures of A. tumefaciens containing pTRV1 and pTRV2 were prepared as previously described (Meng et al., 2013) and syringe-infiltrated into cotyledons of 9 d-old Rio Grande tomato seedlings. Plants were kept for c. 3 wk post infiltration in a growth chamber with 20°C day and 18°C night temperatures in 50% relative humidity with a 16 h photoperiod length. Plants were transferred to 24°C day and 20°C night temperatures 1 wk before performing ROS assays.

Swim plate assay for quantifying bacterial motility

Swim plates were prepared by making King’s B medium (King et al., 1954) plates with 0.3% agar. Swim plates were always prepared the same day as used. Plates were inoculated via ‘toothpick inoculation’ using a 2μL pipette tip (Rainin, Columbus, OH, USA) by placing the tip in 1-d-old bacterial colonies on a plate and then gently placing the pipette tip on the swim plate. The pipette tip was always placed aligned with radial lines of the plate. The plates were then placed in a 28°C incubator for 2 d. The diameter of swimming of each strain was measured using a ruler held perpendicular to the radial lines of the plate and therefore perpendicular to the orientation of the pipette tip during inoculation to nullify slight variation resulting from not perfectly consistent pipette tip inoculations. Larger 150 × 15 mm Petri dishes (VWR, Radnor, PA, USA) were used for accommodating 7 bacterial strains on the same swim plate to control for variability among plates.

Deletion of fliC from Pto DC3000

A flagellin-deficient mutant of P. syringae pv tomato (Pto) DC3000 was generated according to the method previously described (Shimizu et al., 2003),. Approximately 0.8 kb fragments located on each side of the fliC were amplified by PCR with primers (Table S1). Each amplified DNA fragment for upstream and downstream regions was ligated at the BamHI site and inserted into the EcoRI site of the mobilizable cloning vector pK18mobsacB. The resulting plasmid containing the DNA fragment lacking fliC was transformed into E. coli S17-1. The fliC deletion mutant was obtained by conjugation and homologous recombination. Specific deletions were confirmed by PCR using primers PC1 and PC4.

Cloning of fliC and complementation of Pto DC3000ΔfliC

Genomic DNA was extracted from the Pto strains DC3000, K40, T1, and ES4326 and used as a template for PCR amplification of fliC. Primers (Table S1) were designed to amplify 326bp upstream (except for ES4326 with 327bp upstream) and 52bp downstream of the fliC ORF with Sac1 and Xho1 restriction enzyme sites on the forward and reverse primers respectively. This region contains both the fliC ORF and nearly the entire flanking regions up to the flanking genes in the flagellum gene cluster. PCR products were cleaned using AccuPrep PCR purification kit (Bioneer, Alameda, CA, USA) and digested by SacI and XhoI (NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA) at 37°C for 3 h. The broad expression vector pME6010 was similarly digested with SacI and XhoI. All digested products were separated using gel electrophoresis and cleaned using AccuPrep gel extraction kit (Bioneer) and each PCR product was individually ligated into the digested pME6010 vector using DNA ligase (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan). Because of the orientation of restriction enzyme sites in the multiple cloning site of pME6010, each PCR product was ligated 3′ to 5′ with respect to the Pk promoter of 6010; therefore, fliC is under control of its native promoter in these vectors. The resulting vectors were transformed via conjugation into Pto DC3000ΔfliC.

Plant protection assay and plant infection assays

Plant protection assays were performed similar to previously described protocols (Zipfel et al., 2004; Cai et al., 2011). 16 h before infection, 1μM of each peptide was infiltrated into the adaxial side of at least 5 attached leaves on 2–4 different 4- or 5-wk-old plants via blunt end syringe and marked to indicate sites of infiltration. Plants were placed in high humidity for 16 h before spray inoculation of 10ml of bacterial suspension per pot at an OD600 of 0.01 using a Preval® sprayer. Silwet L-77 was not added to the bacterial suspension to avoid creating artificial conditions where flagella are likely less essential. The plants were then covered with clear plastic flat covers to maintain high humidity for 16 h following inoculation. After the number of days indicated in each figure legend, regions of leaves that had been previously infiltrated by peptide were removed using a 0.52mm2 cork borer and placed in a tube containing 200μL of 10mM MgSO4 solution and three 2mm glass beads. The tube was placed in a mini bead beater (Biospec Products, Inc., Bartlesvill, OK, USA) and shaken for 90 s to grind the leaf and release endophytic bacteria. This suspension was diluted in 10mM MgSO4 and plated on a King’s B media plate with appropriate antibiotic selection. After 2 d, colony-forming units were counted. Similar procedures were used to quantify growth of the Pto DC3000ΔfliC strains on A. thaliana and S. lycopersicum. A. thaliana fls2 mutant plants (Xiang et al., 2008) were kindly provided by Jian-min Zhou.

For inoculation by infiltration, plants were infiltrated via a blunt-end syringe at an OD600 of either 1 × 10−3 (Arabidopsis) or 1 × 10−4 (tomato). Population assays were performed as described above.

Results

Diversity exists in flg22 and flgII-28 in the P. syringae species complex

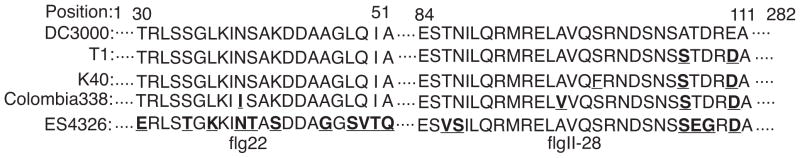

Since we had found unexpected diversity among Pto strains in both the flg22 and flgII-28 epitopes (Cai et al., 2011), we assembled the flg22 and flgII-28 alleles from all available genomes of the P. syringae species complex. The positions within flg22 and flgII-28 that are mutated in Pto strains are conserved in P. syringae strains belonging to other pathovars (Table S2); however, some strains show overall sequence variation in both epitopes, particularly P. syringae pv. maculicola ES4326, a strain recently reassigned to P. cannabina pv. alisalensis (Pcal) (Bull et al., 2010). The subset of flg22 and flgII-28 alleles tested in this paper are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Alignment of flg22 and flgII-28 regions of FliC of the six Pto strains (listed on left) used in this study. Numbers on top row indicate the amino acid positions within the flagellin protein. Bold/underlined letters indicate single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs).

Mapping the locations of flg22 and flgII-28 to the known flagellin structure (Yonekura et al., 2003) revealed that flg22 and flgII-28 are structurally similar regions of flagellin: both are found within loop regions located between alpha helices (data not shown). Loops define the angle between flanking alpha helixes and are thus important determinants of protein structure, which may in fact explain the relative sequence conservation of both flg22 and flgII-28.

flgII-28 recognition is limited to a subset of the Solanaceae family

We have previously shown that the flgII-28 alleles of Pto strains K40 (same genotype as LNPV17.41) and Col338 trigger less ROS production and less stomatal closure than the flgII-28 allele of Pto T1 on tomato cv ‘Chico III’(Cai et al., 2011). To test whether plants other than tomato can recognize flgII-28, ROS production was measured in 18 different plant genotypes across six different families, with multiple Brassicaceae and Solanaceae species tested. The posterior probability (P(H0|Data)) that the observed data for each plant-peptide combination can be fit to a function with no slope (i.e. no ROS production; see methods for more details) was then calculated. While flg22T1 triggered ROS generation in 15 of the tested plants, flgII-28T1 triggered ROS production only in 6 tested plants – all of which were in the Solanaceae family (Table 1). Two of the plants that did not respond to flg22T1 were ecotypes of Arabidopsis known to be defective in the FLS2 locus: Ws-0 (Gómez-Gómez et al., 1999) and Cvi-0 (Dunning et al., 2007); the third was celery (Apium graveolens). The flgII-28T1 peptide, on the other hand, only elicited ROS in the three tested tomato cultivars, the two tested cultivars of pepper (Capsicum annuum), and the one tested cultivar of potato (Solanum tuberosum) (Table 1). Graphical representations of select ROS curves are depicted in Fig. S2.

Table 1.

Production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in response to either flg22T1 or flgII-28T1 across the plant kingdom

| Elicitor: | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| flg22 | flgII-28 | ||

|

| |||

| Plant | cv/eco. | P(H0|Data)a | P(H0|Data)a |

| Brassicaceae | |||

| Arabidopsis | Ws-0 | \ (0.98) | \ (0.99) |

| Arabidopsis | Cvi-0 | \ (1.00) | \ (0.99) |

| Arabidopsis | Col-0 | + (0.00) | \ (0.98) |

| Cauliflower | Toscana 2 | + (0.00) | \ (0.96) |

| Turnip | P. T. W. Globe | + (0.00) | \ (0.99) |

| Radish | Champion | + (0.00) | \ (0.99) |

| Fabaceae | |||

|

| |||

| Bean | Red Mex | + (0.00) | \ (0.20) |

| Convolvulaceae | |||

|

| |||

| Morning Glory* | - | + (0.03) | \ (0.70) |

| Apiaceae | |||

|

| |||

| Celery | S. V. Pascal | \ (0.96) | \ (0.76) |

| Plantaginaceae | |||

|

| |||

| Snapdragon | Cook’s Tall | +\ (0.11) | \ (0.79) |

| Solanaceae | |||

|

| |||

| Tomato | ChicoIII | + (0.00) | + (0.00) |

| Tomato | Sunpride | + (0.00) | + (0.00) |

| Tomato | Rio Grande | + (0.00) | + (0.00) |

| Potato | Red Maria | +\ (0.15) | + (0.00) |

| Bell Pepper | CA Wonder | + (0.00) | + (0.00) |

| Jalap. Pepper | Early | + (0.00) | + (0.00) |

| Eggplantb | MM643 | + (0.00) | \ (1.00) |

| Tobacco | Burly | + (0.00) | \ (0.99) |

| N. benthamiana | - | + (0.00) | \ (0.99) |

ROS response of selected species of the Brassicaceae, Solanaceae and other plant families to flg22 and flgII-28 peptides. +, strong response; \, no response; +\, weak to no response. Data represent the analysis from one experiment of 6 leaf punches. Similar results were obtained in 2–12 independent experiments (plants tested in only 2 experiments labeled with *).

Posterior probability of the data being fit to the null model (no response – the function being fit is a flat line with no slope) explaining the observed data (i.e. the probability that there is no measurable production of ROS). See the Materials and Methods section for more details.

In ~25% of experimental repeats flgII-28 did trigger significant amounts of ROS production cautioning the variability among plants in this assay.

The relative strength of the immune response triggered by flgII-28 and flg22 alleles is dependent on plant genotype

To test whether the derived flgII-28 alleles (flgII-28K40 and flgII-28Col338) are generally weaker elicitors of PTI compared to the ancestral flgII-28T1 allele, we performed ROS analyses for both the ancestral and derived flgII-28 peptides on all Solanaceae tested above. We indeed observed that the derived alleles of flgII-28 triggered significantly less ROS than flgII-28T1 on both tested cultivars of tomato. By contrast, the derived alleles of flgII-28 triggered only slightly less ROS on pepper (Fig. 2).

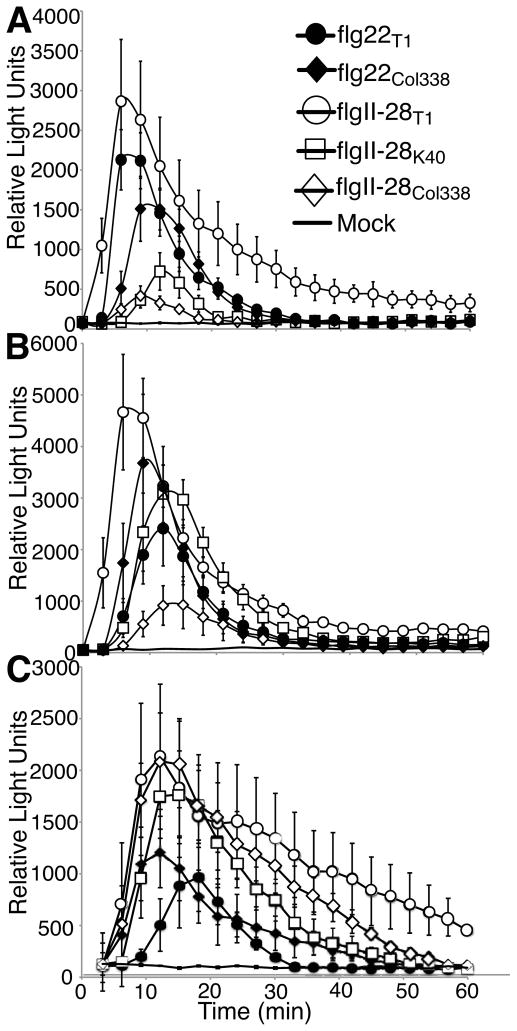

Fig. 2.

Pepper and tomato plants differ in their relative sensitivity to the flgII-28 alleles from Pto strains T1, Col338, and K40. Leaf punches of either Solanum lycopersicum cv ‘Rio Grande’ (a), Solanum lycopersicum cv ‘Sunpride’ (b), or Capsicum annuum cv ‘Jalapeno Early’ (c) were treated with 1μM (a, b) or 100nM (c) of indicated peptides and reactive oxygen species (ROS) was measured for 1 h immediately following treatment. Data shown are the average of 6 replicate leaves and error bars represent ± SE. Similar results were obtained in at least 4 independent experiments.

To determine if differences in ROS elicitation were statistically relevant, we modeled the ROS data for each plant-peptide combination using a shifted Gompertz-decay curve and determined differences in the kinetics of the ROS response between different peptides on the same plants (See the Materials and Methods section, Methods S1, and Fig. S1 for more information). Using this approach to compare the ROS curves depicted in Fig. 2, flgII-28K40 and flgII-28Col338 were found to give rise to ROS elicitation with significantly lower peak intensity and longer offset than flgII-28T1 in both tomato cv ‘Rio Grande’ and tomato cv ‘Sunpride’. Contrastingly, no significant differences among peptides were detected in ROS elicitation in pepper cv ‘Jalapeno Early’ (Tables S3, S4). Extending this statistical analysis to all other plants capable of detecting flgII-28T1 (Table 1), flgII-28K40 and flgII-28Col338 were found to elicit significantly less ROS than flgII-28T1 on potato cv ‘Red Maria’ and tomato cv ‘Chico III’. However, as for pepper cv ‘Jalapeno Early’, the derived flgII-28 peptides do not trigger significantly less ROS on pepper cv ‘CA Wonder’ (Tables S5, S6).

A single nonsynonymous SNP distinguishes the flg22 allele of the Pto strain Col338 from the flg22 allele present in all other Pto strains including Pto DC3000 and T1 (Fig. 1). Peptides of this flg22 variant triggered stronger responses in some Solanaceae but weaker responses in others when compared to flg22DC3000 (Fig. 2, Tables S7 and S8).

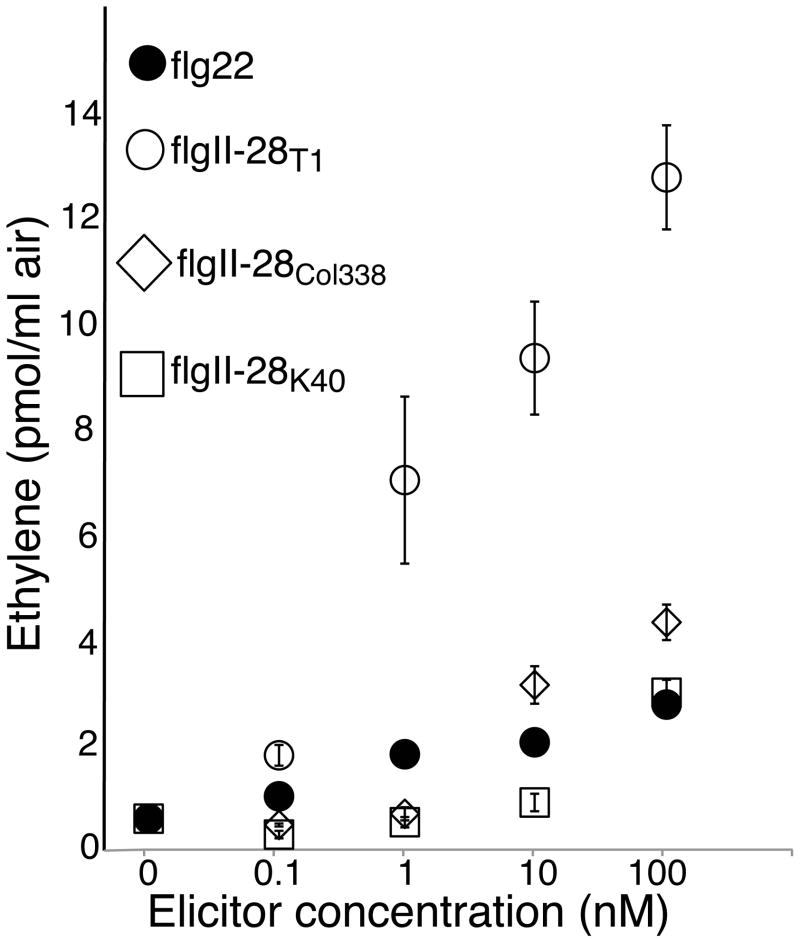

Ethylene production is another quantifiable PTI response (Boller and Felix, 2009). Fig. 3 shows that flgII-28K40 and flgII-28Col338 elicit significantly less ethylene biosynthesis in tomato cv ‘Money Maker’ than flgII-28T1 further confirming that flgII-28K40 and flgII-28Col338 trigger weaker immune responses in tomato compared to flgII-28T1. Moreover, flgII-28T1 is at least as active in eliciting ethylene biosynthesis in tomato as flg22.

Fig. 3.

Pattern-triggered immunity (PTI)-responses of tomato to flgII-28 alleles from Pto strains T1, Col338, and K40. Leaf strips of 4-wk-old Solanum lycopersicum cv ‘Money Maker’ were treated with the indicated peptides at concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 100nM and ethylene accumulating during 4 h of treatment was measured. Data shown are the average of 4 replicates and error bars represent ± SE. Similar results were obtained in 2 independent experiments.

Overall, these data indicate that allelic variability in both epitopes of flagellin and in the plant PRRs that recognize them determine the intensity of PTI suggesting co-evolution between MAMPs and PRRs. We conclude that the derived lineages of Pto have evolved to avoid flagellin recognition by S. lycopersicum and/or S. tuberosum (and possibly other related Solanaceae not tested here) but these mutations in flagellin do not make it universally stealthier in all plant interactions.

Arabidopsis cannot perceive flgII-28 peptide

We further tested the ability of A. thaliana to detect flgII-28 in four independent PTI assays: the plant protection assay (Zipfel et al., 2004), callose deposition (Adam & Somerville, 1996), ethylene production (Boller & Felix, 2009), and cell culture alkalinization (Meindl et al., 1998). All four assays confirmed that Arabidopsis does not respond to flgII-28 peptide (Fig. S3A,B,E,F). We also observed that the flgII-28 allele of the Arabidopsis and tomato pathogen Pto DC3000, which differs by two amino acid residues from flgII-28T1 (Fig. 1), does not elicit ROS in A. thaliana either (Fig. S3C), nor do two other alleles of Pto flgII-28 (Fig. S3D). Overall, detection of flgII-28 seems limited to a subset of species in the Solanaceae family, contrasting with flg22, which is broadly recognized across the plant kingdom (Albert et al., 2010).

FLS2 is not sufficient for recognition of flgII-28

To test whether flgII-28 is recognized by FLS2, we transiently expressed FLS2 from either tomato cv ‘Roter Gnom’ (Robatzek et al., 2007), which is capable of detecting both flgII-28 and flg22 (Fig. S4), or A. thaliana, which is non-responsive to flgII-28 (Table 1), in non-responsive N. benthamiana plants. Plants were treated with flg22, flgII-28, or flg15E. coli – a truncation variant of flg22 that is recognized by tomato but not by A. thaliana or N. benthamiana (Bauer et al., 2001; Robatzek et al., 2007). Both FLS2 proteins accumulated in N. benthamiana (Fig. S5), and expression of SlFLS2 conferred to N. benthamiana responsiveness to flg15E. coli (Fig. 4a), confirming functionality of the receptor. However, transient expression of either allele of FLS2 did not confer responsiveness to flgII-28 (Fig. 4a).

Addition of flgII-28 peptide to a S. peruvianum cell culture saturated for the flg22 response triggers a further increase in extracellular alkalinization, and, vice versa, addition of flg22 peptide to S. peruvianum cell culture saturated for the flgII-28 peptide triggers further increase in extracellular alkalinization (Fig. 4b). Taken together, these results suggest that flgII-28 is recognized by a PRR distinct from FLS2.

Moreover, virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) of FLS2 in tomato had no effect on flgII-28 recognition but significantly attenuated ROS production elicited by flg22 treatment (Fig. 4c). Recent sequencing of the tomato genome (Consortium, 2012) revealed a close paralog located adjacent to the original FLS2 on chromosome 2, which we designated as FLS2.2. The DNA fragment in our FLS2-VIGS construct, cloned using FLS2.1 (Solyc02g070890) has 8 stretches of at least 21 nucleotides with perfect identity to FLS2.2, (Solyc02g070910) and expression of both genes was decreased by c. 40% (Fig. S6). These data suggest that neither copy of SlFLS2 contributes to recognition of flgII-28.

However, pretreatment of tomato leaf disks with flg22 significantly reduced ROS elicitation by subsequent addition of flg22 or flgII-28 relative to mock pretreatment (Fig. 4d) suggesting that flg22 and flgII-28 recognition share at least one common downstream signaling component. Because flgII-28 typically elicits significantly more ROS than flg22 in tomato, this result is not simply due to exhaustion of reagents used in the assay or exhaustion of ROS substrates within cells following flg22 pretreatment.

Alleles of Pseudomonas syringae flg22 are not universally recognized in either Brassicaceae or Solanaceae

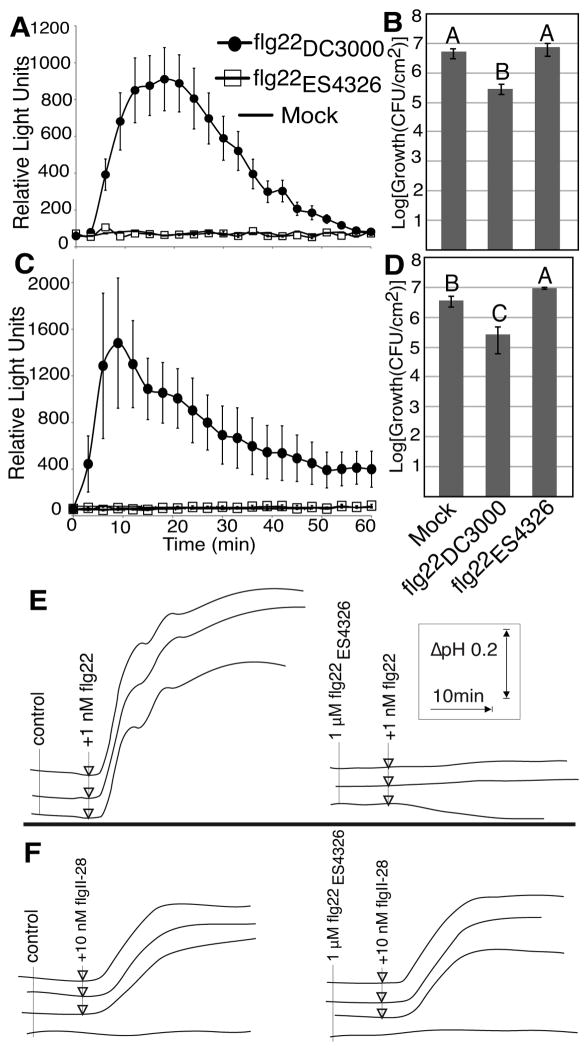

The recently sequenced Pcal ES4326 strain (Baltrus et al., 2011) causes disease in Arabidopsis (Dong et al., 1991) and is related to strains that cause disease on various other Brassicaceae (Bull et al., 2010, 2011). Because flg22ES4326 is the most divergent flg22 allele compared to all other known P. syringae flg22 epitopes (only 12 identities between flg22ES4326 and flg22DC3000; Fig. 1; Table S2), we hypothesized that ES4326 and ES4326-like strains evolved a flg22 sequence adapted to avoid recognition. Indeed, flg22ES4326 failed to elicit PTI based on ROS assays and did not promote resistance to P. syringae in either Arabidopsis (Fig. 5a,b; Table S9) or tomato (Fig. 5c,d; Table S9).

Fig. 5.

The flg22 allele of Pcal ES4326 is inactive as a microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMP) but acts as an antagonist for flg22. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in leaf punches of either A. thaliana ecotype Col-0 (a) or tomato cv ‘Chico III’ (c) with 1μM of indicated peptides. flg22DC3000, circles; flg22ES4326, squares; mock, lines. Data shown are the average of 6 replicate leaves and error bars represent standard error. Similar results were obtained in at least 3 independent experiments. Plant protection in leaves of A. thaliana ecotype Col-0 (b) or tomato cv ‘Chico III’ (d) after infiltration with 1μM flg22 or 1 μM flg22ES4326. Leaves were inoculated with either strain Pto DC3000 (b) or strain Pto DC3000δavrpto1δavrptoB (d) by spray infection 16 h later and total bacterial populations were quantified at 4 d. Different letters indicate significant differences at the 0.05 alpha level in an unpaired Student’s t-test. Data represent the average of 4 replicate leaves and error bars represent standard error. Similar results were obtained in at least 3 independent experiments. (e, f): Extracellular pH in S. peruvianum (wild tomato) cell cultures treated with 1μM flg22ES4326 and 1nM flg22 (e) or 10nM flgII-28 (f) as indicated by the arrows. Each line represents the pH readout from a single well of cell culture.

Therefore, diversity within P. syringae flg22 does not only affect the strength of the PTI response but can even lead to complete avoidance of PTI

When performing plant protection assays in tomato, pretreatment with flg22ES4326 consistently led to more pathogen growth compared to the mock-treated plants (Fig. 5d), a result confirmed on a second tomato cultivar (Fig. S7). We hypothesized that flg22ES4326 may interact with FLS2 in an antagonistic manner, reducing the detection of native flagellin from the pathogen during infection. Such characteristics have been described for truncated versions of flg22 (Felix et al., 1999) and flg22Rsol, the flg22 variant of Ralstonia solanacearum (Mueller et al., 2012). To test this hypothesis we used cultured cells of wild tomato S. peruvianum, which respond to flg22DC3000 and flgII-28T1 with a rapid extracellular alkalinization response (Fig. 5e). As hypothesized, treating the cells with flg22ES4326 did not lead to extracellular alkalinization but inhibited a subsequent response to flg22 (Fig. 5e) confirming that flg22ES4326 acts as an antagonist for flg22 possibly by engaging the FLS2 receptor without triggering an immune response. Notably, pretreatment with flg22ES4326 did not reduce the alkalinization response to flgII-28T1 (Fig. 5f) further corroborating that flgII-28 is not an active ligand for FLS2.

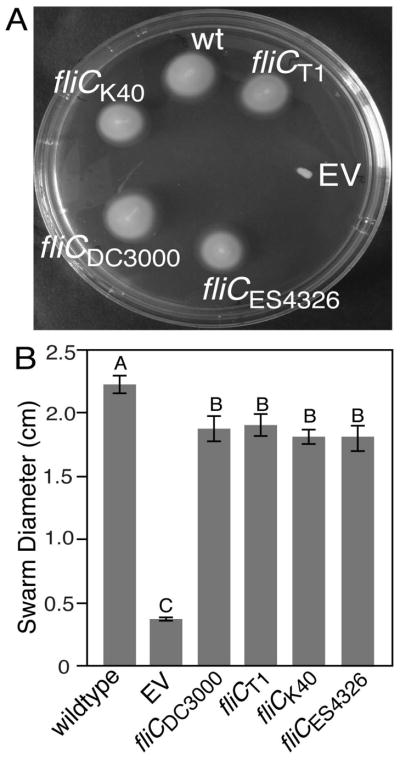

Allelic diversity in FliC does not impact motility in a Pto DC3000δfliC background

MAMPs are considered to be favorite targets for recognition by the plant immune system because they represent conserved structures with essential roles in invariant microbial processes. Thus, we tested whether the observed mutations in flagellin affect the swimming motility of P. syringae, which is the primary function of the flagellum. To quantify swimming motility, soft-agar swim plates were used in which flagellar-motile bacteria will spread from an initial point of inoculation (Hazelbauer et al., 1969). In this assay, wild-type Pto strain K40 and Pcal strain ES4326 both were significantly less motile than the other tested strains (Fig. S8). However, besides the allelic differences in fliC there are many more genetic differences between the analyzed strains. Therefore, to specifically quantify the effect of the fliC SNPs in an isogenic background, we deleted the endogenous fliC gene in Pto DC3000 and complemented it with four different fliC alleles under the control of their native promoters. As expected, Pto DC3000δfliC was found to be significantly impaired in motility. By contrast, strains complemented with the four fliC alleles were indistinguishable from each other and swam out from the initial point of inoculation at a level just below that of wild-type Pto DC3000 (Fig. 6). We conclude that the mutations in flagellin do not substantially affect motility.

Fig. 6.

The alleles of fliC from Pto strains T1, DC3000, K40 and Pcal ES4326 reconstitute motility in Pto DC3000δfliC. (a) Swim size on a KB swim plate (0.3% agar) 2 d following toothpick inoculation with wild-type Pto DC3000 (wt), Pto DC3000δfliC with an empty vector (EV) or Pto DC3000δfliC complemented with the indicated alleles of fliC. (b) Quantification of swim size from 8 replicate plate. Error bars represent ± SE. Letters indicate significant differences at the 0.05 alpha level in an unpaired Student’s t-test. Similar results were obtained in 3 independent experiments.

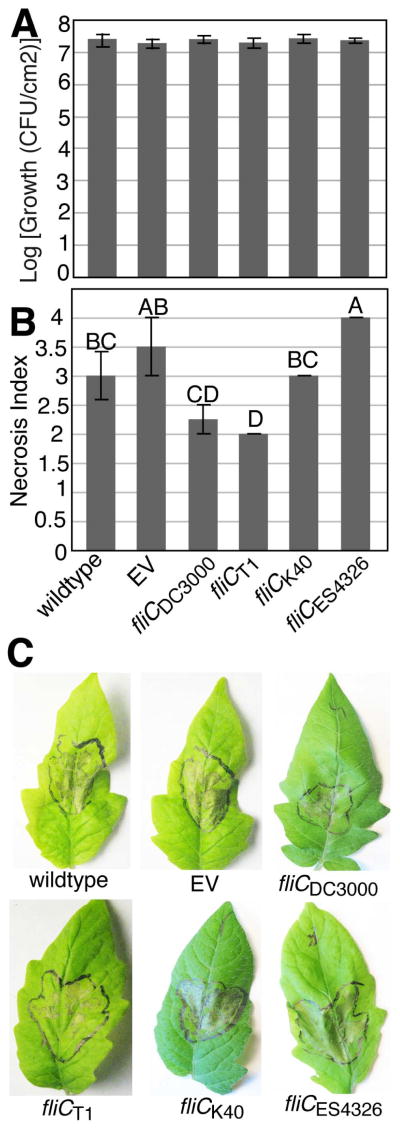

Allelic diversity in fliC affects disease development but not growth of P. syringae in tomato

To test whether the fliC mutations affect bacterial growth in planta, tomato plants were infiltrated with Pto DC3000 wild-type, Pto DC3000δfliC, and the four complemented Pto DC3000δfliC strains described above. We hypothesized that the alleles of fliC containing the stealthier versions of flgII-28 would allow for higher growth compared to Pto DC3000. However, all strains grew to equally high population densities both 3 and 4 d following inoculation by syringe infiltration (Figs S9, 7a, respectively) and spray inoculation (Fig. S10A). It is surprising that even the uncomplemented Pto DC3000δfliC strain was able to reach a population density as high as that of the other strains even following spray inoculation in the absence of a surfactant. We hypothesize that Pto DC3000 either uses forms of motility other than swimming during infection of tomato or that the cost of being non-motile is counterbalanced by lower PTI elicitation due to the absence of flg22 and flgII-28 in this mutant.

Fig. 7.

The different alleles of fliC have no effect on bacterial growth in tomato leaves but contribute differentially to induction of necrosis. (a) 4-wk-old tomato cv ‘Rio Grande’ plants were infiltrated with either wild-type Pto DC3000 (wt), Pto DC3000δfliC with an empty vector (EV) or Pto DC3000δfliC complemented with the indicated alleles of fliC at 1×10−4 O.D. Growth was quantified 4 d following infection. (b) The same plants used to quantify growth were scored for necrosis severity on the scale: 1, no necrosis; 2, moderate necrosis; 3, heavy necrosis; 4, total necrosis. (c) Representative pictures of necrosis induced by the different Pto DC3000δfliC complemented strains. Similar results were obtained in 4 independent experiments. Data shown are the average of 4 replicate leaves and error bars represent ± SE.

Intriguingly, while the various fliC alleles did not affect bacterial growth in the Pto DC3000δfliC background, they did lead to significant differences in the development of leaf necrosis (Fig. 7b,c) suggesting that in planta expression of FliC protein can interfere with symptom development, which was recently demonstrated (Wei et al., 2012), in an allele-dependent manner.

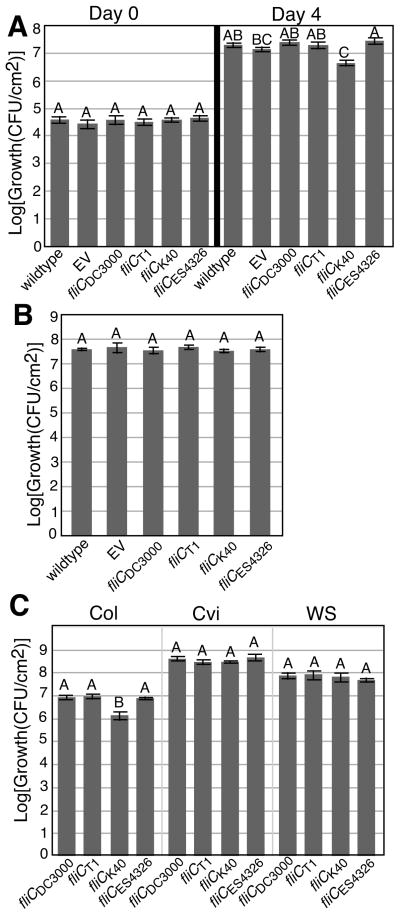

Allelic diversity in fliC affects virulence of P. syringae in Arabidopsis

To test the effects of the identified SNPs in a second pathogen - host interaction, Arabidopsis was inoculated with the complemented Pto DC3000δfliC strains. Interestingly, Pto DC3000δfliC complemented with fliCK40 grew to significantly lower population densities than the other strains following inoculation by infiltration (Fig. 8a). Because flagella are known to play only a minor role in apoplastic growth (Schreiber & Desveaux, 2011), we also queried for differences in fitness among the strains following spray infection and confirmed the fitness defect of Pto DC3000δfliC complemented with fliCK40 (Fig. S10B). Importantly, no surfactants were used in the spray inoculations to avoid creating an artificial condition in which flagella are less important. This strain also triggered less severe disease symptoms (Figs S10D, S11). The difference between Pto DC3000δfliC complemented with either fliCK40 or fliCT1 is particularly intriguing considering that the only amino acid difference between these two strains is a single S→F mutation in the flgII-28 region of flagellin – a region that does not, as an isolated peptide, elicit PTI in Arabidopsis. To determine if the observed differences between the two strains were FLS2-dependent, leaves of an fls2 Arabidopsis mutant line (Xiang et al., 2008) were inoculated by either spraying or infiltration. Interestingly, the differences between the two strains were abolished (Figs 8b, S10C). The differences were also abolished in Arabidopsis ecotypes that have a defect in FLS2 (Fig. 8c). We conclude that diversity in flagellin beyond flg22 can significantly affect P. syringae virulence in an FLS2-dependent manner.

Fig. 8.

The different of alleles of fliC affect virulence on Arabidopsis in an FLS2-dependent manner. 4-wk-old Col-0 wild-type plants (a) or fls2 mutant plants (b) were syringe infiltrated with either wild-type Pto DC3000 (wt), Pto DC3000δfliC with an empty vector (EV) or Pto DC3000δfliC complemented with the indicated alleles of fliC at 1×10−3 O.D. Bacteria were quantified at 0 and 4 d following infection. (c) The indicated strains were syringe infiltrated into either Col-0 or fls2 null ecotypes Ws-0 or Cvi-0 at 1 × 10−3 O.D. Growth was quantified 4 d following infection. Data shown are the average of 8 replicate leaves. Error bars represent ± SE. Similar results for all sections were obtained in at least 3 independent experiments.

To rule out the possibility that the observed differences between complemented Pto DC3000δfliC strains were due to mutations accumulated during the transformation of the Pto DC3000δfliC strain with the different fliC alleles and not due to the different fliC alleles themselves, the results for growth and necrosis development in tomato and growth in Arabidopsis were confirmed with a second set of independently transformed isolates of all strains (Fig. S12).

Discussion

Since flg22 was found to be sufficient to elicit PTI in multiple clades of seed plants belonging to angiosperms and even gymnosperms (Felix et al., 1999; Albert et al., 2010), studies of flagellin-triggered plant immunity have mainly focused on the flg22 epitope, though a flg22-independent flagellin perception system has been proposed for rice (Che et al., 2000). However, in performing a population genomics analysis of a large collection of Pto strains (Cai et al., 2011) we identified a second PTI-eliciting flagellin epitope, flgII-28. Studying pathogen diversity can thus lead to new insights into plant – microbe interactions (Cai et al., 2011) and provides an efficient strategy for the identification of new MAMPs, as recently confirmed by others (McCann et al., 2012).

Continuing characterization of flagellin diversity, here we have shown that: flgII-28 elicits immunity in several Solanaceae species but not in any members of other plant families tested so far; significant and biologically relevant allelic diversity exists at both MAMP loci of flagellin (flg22 and flgII-28), demonstrating the ability of adapted pathogens to overcome PTI through MAMP diversification; allele-dependent differences in PTI are also dependent on plant genotype, implying natural variability in the plant receptor(s) for these epitopes; the PTI-altering mutations in flagellin do not come at the cost of microbial fitness in the tested conditions, suggesting that MAMPs are under weaker purifying selection than previously thought; FLS2 is likely not the flgII-28 receptor although allelic diversity in flgII-28 affects plant virulence in an FLS2-dependent manner in Arabidopsis.

flgII-28 elicits PTI responses in several Solanaceae species

Based on the flgII-28 alleles and plant species analyzed here, recognition of flgII-28 is limited to a subset of Solanaceae species. The most obvious explanation for this result is that flgII-28 recognition evolved in a relatively recent ancestor of some Solanaceae. However, at this point we cannot exclude the possibility that flgII-28 recognition is widespread in the plant kingdom and that the plants that were non-responsive to flgII-28 in this study recognize not yet tested alleles of flgII-28.

Significant diversity in MAMPs and MAMP perception reveals an evolutionary PTI arms race

Because of the relative differences in the strength of PTI triggered in closely related Solanaceae by the different alleles of the flgII-28 peptide, we infer the importance of allelic variability in both MAMPS and corresponding plant PRRs. Also, Vetter et. al. recently described extensive variation in recognition of flg22 across Arabidopsis ecotypes due to allelic differences in FLS2 sequences, differences in FLS2 protein abundance, and differences in downstream signaling components (Vetter et al., 2012). However, the observed variability in flgII-28 recognition among Solanaceae appears to be primarily linked to sequence diversity of a putative flgII-28 receptor. In fact, differences in abundance of a receptor or in elements in downstream signaling between plant species would equally affect recognition of all flgII-28 alleles and not lead to relative differences in recognition of flgII-28 alleles as we observed.

Since flgII-28K40 and flgII-28Col338 elicit less PTI in tomato and almost entirely replaced the ancestral flgII-28T1 alleles in Pto populations in Europe and North America over the last 30 yr, we had hypothesized that these alleles recently evolved under selection pressure in tomato agricultural settings (Cai et al., 2011). However, we had also noticed that the flgII-28K40 allele appeared in two separate genetic lineages of Pto (Cai et al., 2011) suggesting that these alleles might have been acquired through horizontal gene transfer. Since we now found that the same alleles also trigger less PTI in other plants, like potato, it is plausible that these alleles pre-existed in the P. syringae population, had evolved under selection pressure for PTI-avoidance on hosts other than tomato, and were only later acquired by Pto through horizontal gene transfer.

On the other hand, the significant reduction in bacterial growth and disease development in Arabidopsis during Pto DC3000 infection due to the flagellin allele of Pto K40 compared to Pto DC3000 shows that adaptation for PTI avoidance on some plant species (here tomato) may have a collateral effect of increasing PTI on other plants (here Arabidopsis). This may explain why the mutations that gave rise to the flgII-28 alleles of Pto K40 and Col338 are not present in any other sequenced P. syringae strains. For the first time, effects of flg22 and flgII-28 on bacterial growth were observed by expressing different fliC alleles under their native promoters in the same genetic pathogen background during infection. These results thus reveal the biological significance of allelic diversity in MAMPs.

The complete absence of PTI elicited by the flg22 allele of Pcal ES4326 in Arabidopsis and tomato is also remarkable. Interestingly, Pcal ES4326 does not have the effector avrPto, which interferes with FLS2 kinase activity (Baltrus et al., 2011) and the PcalES4326 homolog of the effector avrPtoB is missing the ubiquitin-ligase domain which has been reported to ubiquitinate FLS2 leading to its degradation (Guttman et al., 2002). This suggests that evasion of PTI through allelic diversification at MAMP loci is similarly efficient in overcoming PTI as delivery of PTI-suppressing effector proteins.

Diversity in flg22 and flgII-28 among closely related pathogens is particularly striking because MAMPs are considered to be essential for important functions (Jones & Dangl, 2006; Bittel & Robatzek, 2007; Lacombe et al., 2010), such as motility in the case of flagellin, and thus under purifying selection. However, to our surprise, none of the differences in flg22 or flgII-28 led to deficiencies in motility in vitro when placed in the same genetic background (Pto DC3000δfliC) demonstrating that there is significant room for divergence at both of these epitopes without cost to motility, thus unsettling the theory that PTI is more evolutionarily stable than its effector-recognizing corollary –Effector Triggered Immunity. Importantly, the differences in flgII-28 and flg22 within the Pto lineage are the only polymorphisms in FliC; therefore, the success of these mutations cannot be explained by intragenic compensatory changes, which have previously been implicated as essential for bacteria to mutate MAMPs to avoid recognition but maintain function (Andersen-Nissen et al., 2005).

What is the flgII-28 receptor?

In bacterial flagellin, flg22 and flgII-28 are physically linked by a stretch of only 33aa residues, hinting at the possibility that both epitopes might act via the same receptor, FLS2. However, when applied as separate synthetic peptides both epitopes act as distinct and independent MAMPs on tomato cells. For example, cells pretreated with highly saturating concentrations of one of the peptides still respond to the other peptide with further response (Fig. 4b). Therefore, the hypothesis of FLS2 as receptor for both epitopes would imply that: flgII-28 and flg22 have distinct binding sites within FLS2 because the two peptides do not compete for binding (Fig. 4b); and that binding of flgII-28 is a peculiar feature of some of the Solanaceous FLS2 orthologs. As an argument against this hypothesis, we observed that gene silencing of FLS2 in tomato attenuated the response to flg22 but not flgII-28 in the ROS assays. Importantly also, heterologous expression of the tomato ortholog Sl FLS2 is not sufficient to confer recognition of flgII-28 to N. benthamiana. This strongly suggests that tomato has at least one additional factor that specifies perception of flgII-28. We tentatively termed this yet-to-be-identified factor FLS3 (Flagellin sensing3). At present, we cannot exclude a role of FLS2 in perception of flgII-28. For example, the postulated FLS3 might be a co-receptor or signaling component that is specifically required for FLS2-dependent detection of flgII-28 and only present in Solanaceae species that respond to flgII-28. However, based on the cumulative evidence from our experiments, we rather conclude that it is more likely that the postulated FLS3 acts as the genuine receptor for flgII-28. Candidates for such a FLS3 receptor are among the hundreds of orphan RLKs and receptor-like proteins in higher plants, many of which show species specific variation that could fit to the occurrence of flgII-28 perception in plants.

However, if FLS2 is not the flgII-28 receptor, how can we explain the FLS2-dependent virulence effect of mutations in flgII-28 during infection of Arabidopsis? Multiple assays showed that flgII-28 peptide itself is not an elicitor in Arabidopsis (Fig. S2) and flgII-28 variants only had an FLS2-dependent virulence effect when in the context of the entire FliC protein. Therefore, Arabidopsis might have an FLS3 allele that cannot bind flgII-28 peptide by itself but requires a larger region of FliC for interacting with flgII-28. FLS2 may act as a necessary co-receptor for FLS3 and FLS2-flg22 binding may even be necessary to place the flgII-28 region of FliC in proximity of the flgII-28 binding site of FLS3. This is reminiscent of the mammalian macrophage flagellin receptor NLCR4 which acts as a co-receptor hub for multiple MAMPs – both flagellin and Type III secretion system components – after the elicitors bind to the NOD-like receptors NAIP5 and NAIP2 respectively (Kofoed & Vance, 2011; Zhao et al., 2011). An equally likely alternative hypothesis is that mutations in flgII-28 lead to FLS2-dependent PTI modulation through an indirect mechanism. For example, mutations in flgII-28 may alter the release of flagellin monomers during flagella assembly or they may cause conformational changes in the FliC structure altering the exposure of flg22 to FLS2.

An emerging parallel in plant and animal innate immunity

Interestingly, the proposed TLR5 recognition site of flagellin in animals (Yoon et al., 2012) partially overlaps with flgII-28 while flg22 seems not to play any role in TLR5 –flagellin binding. Therefore, future studies of FLS3-mediated recognition of flagellin in plants, in particular, identification of FLS3 and elucidation of flgII-28-FLS3 interaction will be highly informative in unraveling a new, intriguing example of convergent evolution in plants and animals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank John McDowell for discussions and critical review of the manuscript. Research in the Vinatzer lab is supported by the NSF (Grant #0746501), the Chinchilla lab by the Swiss National Foundation (Grant# 31003A_138255), and in the Martin lab by the NSF (Grant #IOS-1025642), the NIH (Grant # R01-GM078021) and the TRIAD Foundation.

Footnotes

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

Fig. S1 Schematic of the 5 parameters analyzed for comparison of ROS generated by the various elicitors. See methods for more details.

Fig. S2 Representative ROS curves from several data sets presented in Table 1.

Fig. S3 Arabidopsis is blind to flgII-28.

Fig. S4 Both flg22 and flgII-28 elicit production of ROS on tomato cv. ‘Roter Gnom’.

Fig. S5 Transient expression of FLS2 led to stable heterologous expression of FLS2 proteins in N. benthamiana.

Fig. S6 Transcript abundance of both FLS2 genes were reduced in FLS2-VIGS tomato plants.

Fig. S7 Pretreatment with flg22ES4326 leads to increased growth in a plant protection assay on tomato cv. ‘Rio Grande’.

Fig. S8 Diversity in motility in vitro exists in the P. syringae species complex.

Fig. S9 The different alleles of fliC do not lead to varying growth on tomato before the onset of necrosis symptoms.

Fig. S10 Similar results as shown in Figs 7 and 8 (infiltration inoculation) are also observed following spray inoculation.

Fig. S11 Disease symptoms of Arabidopsis following infection with strains used in Fig. 8.

Fig. S12 Growth of second isolates of the DC3000δfliC strain complemented with the different alleles of fliC.

Table S1 Primers used in this study

Table S2 Alleles of flg22 and flgII-28 present in P. syringae sensu lato species complex

Table S3 Difference in ROS response of Solanaceae plants shown in Fig. 2 to either the T1 allele or the K40 allele of flgII-28

Table S4 Difference in ROS response of Solanaceae plants shown in Fig. 2 to either the T1 allele or theCol338 allele of flgII-28

Table S5 Difference in ROS response of other Solanaceae plants to either the T1 allele or the K40 allele of flgII-28

Table S6 Difference in ROS response of other Solanaceae plants to either the T1 allele or theCol338 allele of flgII-28

Table S7 Difference in ROS response of Solanaceae plants shown in Fig. 2 to either the T1 allele or theCol338 allele of flg22

Table S8 Difference in ROS response of other Solanaceae plants to either the T1 allele or theCol338 allele of flg22

Table S9 Analysis of the ROS response of either A. thaliana or tomato to either flg22DC3000 or flg22ES4326 shown in Figs 5(a,b).

Methods S1 Bayesian analysis of dynamics of Reactive Oxygen species; Callose deposition; FLS2 protein detection; Quantitative real time reverse transcription PCR

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting information supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the New Phytologist Central Office.

References

- Adam L, Somerville SC. Genetic characterization of five powdery mildew disease resistance loci in Arabidopsis thaliana. The Plant Journal. 1996;9:341–356. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1996.09030341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert M, Jehle KA, Lipschis M, Mueller K, Zeng Y, Felix G. Regulation of cell behaviour by plant receptor kinases: pattern recognition receptors as prototypical models. European Journal of Cell Biology. 2010;89:200–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen-Nissen E, Smith KD, Strobe KL, Barrett SLR, Cookson BT, Logan SM, Aderem A. Evasion of Toll-like receptor 5 by flagellated bacteria. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2005;102:9247–9252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502040102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel FM. Are innate immune signaling pathways in plants and animals conserved? Nat Immunol. 2005;6:973–979. doi: 10.1038/ni1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltrus DA, Nishimura MT, Romanchuk A, Chang JH, Mukhtar MS, Cherkis K, Roach J, Grant SR, Jones CD, Dangl JL. Dynamic evolution of pathogenicity revealed by sequencing and comparative genomics of 19 Pseudomonas syringae isolates. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002132. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer Z, Gomez-Gomez L, Boller T, Felix G. Sensitivity of different ecotypes and mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana toward the bacterial elicitor flagellin correlates with the presence of receptor-binding sites. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:45669–45676. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102390200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittel P, Robatzek S. Microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) probe plant immunity. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2007;10:335–341. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boller T, Felix G. A renaissance of elicitors: perception of microbe-associated molecular patterns and danger signals by pattern-recognition receptors. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2009;60:379–406. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudsocq M, Willmann MR, McCormac M, Lee H, Shan L, He P, Bush J, Cheng SH, Sheen J. Differential innate immune signalling via Ca2+ sensor protein kinases. Nature. 2010;464:418–422. doi: 10.1038/nature08794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull CT, Clarke CR, Cai R, Vinatzer BA, Jardini TM, Koike ST. Multilocus Sequence Typing of Pseudomonas syringae sensu lato confirms previously described genomospecies and permits rapid identification of P. syringae pv. coriandricola and P. syringae pv. apii causing bacterial leaf spot on parsley. Phytopathology. 2011;101:847–858. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-11-10-0318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull CT, Manceau C, Lydon J, Kong H, Vinatzer BA, Fischer-Le Saux M. Pseudomonas cannabina pv. cannabina pv. nov., and Pseudomonas cannabina pv. alisalensis (Cintas Koike and Bull, 2000) comb. nov., are members of the emended species Pseudomonas cannabina (ex Sutic & Dowson 1959) Gardan, Shafik, Belouin, Brosch, Grimont & Grimont 1999. Systematic and Applied Microbiology. 2010;33:105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai R, Lewis J, Yan S, Liu H, Clarke CR, Campanile F, Almeida NF, Studholme DJ, Lindeberg M, Schneider D, et al. The Plant Pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato is genetically monomorphic and under strong selection to evade tomato immunity. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002130. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarthy S, Velasquez AC, Ekengren SK, Collmer A, Martin GB. Identification of Nicotiana benthamiana genes involved inpathogen-associated molecular pattern-triggered immunity. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions. 2010;23:715–726. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-23-6-0715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che FS, Nakajima Y, Tanaka N, Iwano M, Yoshida T, Takayama S, Kadota I, Isogai A. Flagellin from an incompatible strain of Pseudomonas avenae induces a resistance response in cultured rice cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:32347–32356. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004796200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng W, Munkvold KR, Gao H, Mathieu J, Schwizer S, Wang S, Yan Y-b, Wang J, Martin GB, Chai J. Structural analysis of Pseudomonas syringae AvrPtoB bound tohost BAK1 reveals two similar kinase-interacting domains in a type III effector. Cell host & microbe. 2011;10:616–626. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinchilla D, Bauer Z, Regenass M, Boller T, Felix G. The Arabidopsis receptor kinase FLS2 binds flg22 and determines thespecificity of flagellin perception. The Plant Cell. 2006;18:465–476. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.036574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinchilla D, Boller T, Robatzek S. Flagellin signalling in plant immunity. In: Lambris JD, editor. In current topics in innate immunity. New York, USA: Springer; 2007a. pp. 358–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinchilla D, Zipfel C, Robatzek S, Kemmerling B, Nurnberger T, Jones JDG, Felix G, Boller T. A flagellin-induced complex of the receptor FLS2 and BAK1 initiates plant defence. Nature. 2007b;448:497–500. doi: 10.1038/nature05999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm ST, Coaker G, Day B, Staskawicz BJ. Host–microbe interactions: shaping the evolution of the plant immune response. Cell. 2006;124:803–814. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consortium TG. The tomato genome sequence provides insights into fleshy fruit evolution. Nature. 2012;485:635–641. doi: 10.1038/nature11119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunnac S, Chakravarthy S, Kvitko BH, Russell AB, Martin GB, Collmer A. Genetic disassembly and combinatorial reassembly identify a minimal functional repertoire of type III effectors in Pseudomonas syringae. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108:2975–2980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013031108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, Mindrinos M, Davis KR, Ausubel FM. Induction of Arabidopsis defense genes by virulent and avirulent Pseudomonas syringae strains and by a cloned avirulence gene. The Plant Cell. 1991;3:61–72. doi: 10.1105/tpc.3.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunning FM, Sun W, Jansen KL, Helft L, Bent AF. Identification and mutational analysis of Arabidopsis FLS2 leucine-rich repeat domain residues that contribute to flagellin perception. The Plant Cell. 2007;19:3297–3313. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.048801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix G, Duran JD, Volko S, Boller T. Plants have a sensitive perception system for the most conserved domain of bacterial flagellin. The Plant Journal. 1999;18:265–276. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Gomez L, Boller T. FLS2: an LRR receptor-like kinase involved in the perception of the bacterial elicitor flagellin in Arabidopsis. Molecular Cell. 2000;5:1003–1011. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80265-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Gómez L, Felix G, Boller T. A single locus determines sensitivity to bacterial flagellin in Arabidopsis thaliana. The Plant Journal. 1999;18:277–284. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttman DS, Vinatzer BA, Sarkar SF, Ranall MV, Kettler G, Greenberg JT. A functional screen for the Type III (Hrp) secretome of the plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae. Science. 2002;295:1722–1726. doi: 10.1126/science.295.5560.1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi F, Smith KD, Ozinsky A, Hawn TR, Yi EC, Goodlett DR, Eng JK, Akira S, Underhill DM, Aderem A. The innate immune response to bacterial flagellin is mediated by Toll-like receptor 5. Nature. 2001;410:1099–1103. doi: 10.1038/35074106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazelbauer GL, Mesibov RE, Adler J. Escherichia coli mutants defective in chemotaxis toward specific chemicals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1969;64:1300–1307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.64.4.1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heese A, Hann DR, Gimenez-Ibanez S, Jones AME, He K, Li J, Schroeder JI, Peck SC, Rathjen JP. The receptor-like kinase SERK3/BAK1 is a central regulator of innate immunity in plants. PNAS. 2007;104:12217–12222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705306104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JDG, Dangl JL. The plant immune system. Nature. 2006;444:323–329. doi: 10.1038/nature05286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King EO, Ward MK, Raney DE. Two simple media for teh demonstration of pyocyanin and fluorescin. Journal of Lab Clinical Medicine. 1954;44:301–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kofoed EM, Vance RE. Innate immune recognition of bacterial ligands by NAIPs determines inflammasome specificity. Nature. 2011;477:592–595. doi: 10.1038/nature10394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacombe S, Rougon-Cardoso A, Sherwood E, Peeters N, Dahlbeck D, van Esse HP, Smoker M, Rallapalli G, Thomma BPHJ, Staskawicz B, et al. Interfamily transfer of a plant pattern-recognition receptor confers broad-spectrum bacterial resistance. Nat Biotech. 2010;28:365–369. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Schiff M, Dinesh-Kumar SP. Virus-induced gene silencing in tomato. The Plant Journal. 2002;31:777–786. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin GB. Suppression and activation of the plant immune system by Pseudomonas syringae effectors AvrPto and AvrPtoB. In: Martin F, Kamoun S, editors. Effectors in plant-microbe interactions. Wiley-Blackwell; 2012. pp. 123–154. [Google Scholar]

- McCann HC, Nahal H, Thakur S, Guttman DS. Identification of innate immunity elicitors using molecular signatures of natural selection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109:4215–4220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113893109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meindl T, Boller T, Felix G. The plant wound hormone systemin binds with the N-terminal part to its receptor but needs the C-terminal part to activate it. The Plant Cell. 1998;10:1561–1570. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.9.1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meindl T, Boller T, Felix G. The bacterial elicitor flagellin activates its receptor in tomato cells according to the address–message concept. The Plant Cell. 2000;12:1783–1794. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.9.1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melotto M, Underwood W, Koczan J, Nomura K, He SY. Plant stomata function in innate immunity against bacterial invasion. Cell. 2006;126:969–980. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng F, Altier C, Martin GB. Salmonella colonization activates the plant immune system and benefits from association with plant pathogenic bacteria. Environmental Microbiology. 2013 doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller K, Chinchilla D, Albert M, Jehle AK, Kalbacher H, Boller T, Felix G. Contamination risks in work with synthetic peptides: flg22 as an example of a pirate in commercial peptide preparations. The Plant Cell. 2012 doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.093815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nover L, Kranz E, Scharf KD. Growth cycle of suspension cultures of Lycopersicon esculentum and Lycopersicon peruvianum. Biochemie und Physiologie der Pflanzen. 1982;177:483–499. [Google Scholar]

- Pfund C, Tans-Kersten J, Dunning FM, Alonso JM, Ecker JR, Allen C, Bent AF. Flagellin is not a major defense elicitor in Ralstonia solanacearum cells or extracts applied to Arabidopsis thaliana. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions. 2004;17:696–706. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2004.17.6.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen MW, Roux M, Petersen M, Mundy J. MAP Kinase cascades in plant innate immunity. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2012:3. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2012.00169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robatzek S, Bittel P, Chinchilla D, Köchner P, Felix G, Shiu SH, Boller T. Molecular identification and characterization of the tomato flagellin receptor LeFLS2, an orthologue of Arabidopsis FLS2 exhibiting characteristically different perception specificities. Plant Molecular Biology. 2007;64:539–547. doi: 10.1007/s11103-007-9173-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robatzek S, Chinchilla D, Boller T. Ligand-induced endocytosis of the pattern recognition receptor FLS2 in Arabidopsis. Genes & Development. 2006;20:537–542. doi: 10.1101/gad.366506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux M, Zipfel C. In: Receptor kinase interactions: complexity of signalling. in receptor-like kinases in plants. Tax F, Kemmerling B, editors. Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2012. pp. 145–172. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber KJ, Desveaux D. AlgW regulates multiple Pseudomonas syringae virulence strategies. Molecular Microbiology. 2011;80:364–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segonzac Cc, Zipfel C. Activation of plant pattern-recognition receptors by bacteria. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2011;14:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan L, He P, Li J, Heese A, Peck SC, Nürnberger T, Martin GB, Sheen J. Bacterial Effectors Target the Common Signaling Partner BAK1 to Disrupt Multiple MAMP Receptor-Signaling Complexes and Impede Plant Immunity. Cell Host &Microbe. 2008;4:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu R, Taguchi F, Marutani M, Mukaihara T, Inagaki Y, Toyoda K, Shiraishi T, Ichinose Y. The deltafliD mutant of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tabaci which secretes flagellin monomers, induces a strong hypersensitive reaction (HR) in non-host tomato cells. Molecular Genetics and Genomics. 2003;269:21–30. doi: 10.1007/s00438-003-0817-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, Dunning FM, Pfund C, Weingarten R, Bent AF. Within-Species Flagellin Polymorphism in Xanthomonas campestris pv campestris and Its Impact on Elicitation of Arabidopsis FLAGELLIN SENSING2-Dependent Defenses. The Plant Cell. 2006;18:764–779. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.037648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi F, Shimizu R, Inagaki Y, Toyoda K, Shiraishi T, Ichinose Y. Post-translational modification of Flagellin determines the specificity of HR induction. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2003;44:342–349. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcg042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi K, Taguchi F, Inagaki Y, Toyoda K, Shiraishi T, Ichinose Y. Flagellin Glycosylation Island in Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea and Its Role in Host Specificity. Journal of Bacteriology. 2003;185:6658–6665. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.22.6658-6665.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetter MM, He F, Kronholm I, Haweker H, Reymond M, Bergelson J, Robatzek S, de Meaux J. Flagellin perception varies quantitatively in Arabidopsis thaliana and its relatives. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29:1655–1667. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei CF, Hsu ST, Deng WL, Wen YD, Huang HC. Plant Innate Immunity Induced by Flagellin Suppresses the Hypersensitive Response in Non-Host Plants Elicited by Pseudomonas syringae pv. averrhoi. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e41056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang T, Zong N, Zou Y, Wu Y, Zhang J, Xing W, Li Y, Tang X, Zhu L, Chai J, et al. Pseudomonas syringae effector AvrPto blocks innate immunity by targeting receptor kinases. Current Biology. 2008;18:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonekura K, Maki-Yonekura S, Namba K. Complete atomic model of the bacterial flagellar filament by electron cryomicroscopy. Nature. 2003;424:643–650. doi: 10.1038/nature01830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon S-i, Kurnasov O, Natarajan V, Hong M, Gudkov AV, Osterman AL, Wilson IA. Structural Basis of TLR5-Flagellin Recognition and Signaling. Science. 2012;335:859–864. doi: 10.1126/science.1215584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng W, He SY. A prominent role of the Flagellin receptor FLS2 in mediating stomatal response to Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology. 2010 doi: 10.1104/pp.110.157016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Yang J, Shi J, Gong YN, Lu Q, Xu H, Liu L, Shao F. The NLRC4 inflammasome receptors for bacterial flagellin and type III secretion apparatus. Nature. 2011;477:596–600. doi: 10.1038/nature10510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel C, Felix G. Plants and animals: a different taste for microbes? Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2005;8:353–360. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel C, Robatzek S, Navarro L, Oakeley EJ, Jones JDG, Felix G, Boller T. Bacterial disease resistance in Arabidopsis through flagellin perception. Nature. 2004;428:764–767. doi: 10.1038/nature02485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.