Abstract

Objective

Depression in the elderly is associated with multiple adverse outcomes, such as high health service utilization rates, low pharmacological compliance, and synergistic interactions with other comorbidities. Moreover, the help seeking process, which usually starts with the feeling “that something is wrong” and ends with appropriate medical care, is influenced by several factors.

The aim of this study was to explore factors associated with the pathway of help seeking among older adults with depressive symptoms.

Methods

A cross-sectional study of 60-year or older of community dwelling elderly belonging to the largest health and social security system in Mexico was done. A standardized interview explored the process of seeking health care in four dimensions: depressive symptoms, help seeking, help acquisition and specialized mental health.

Results

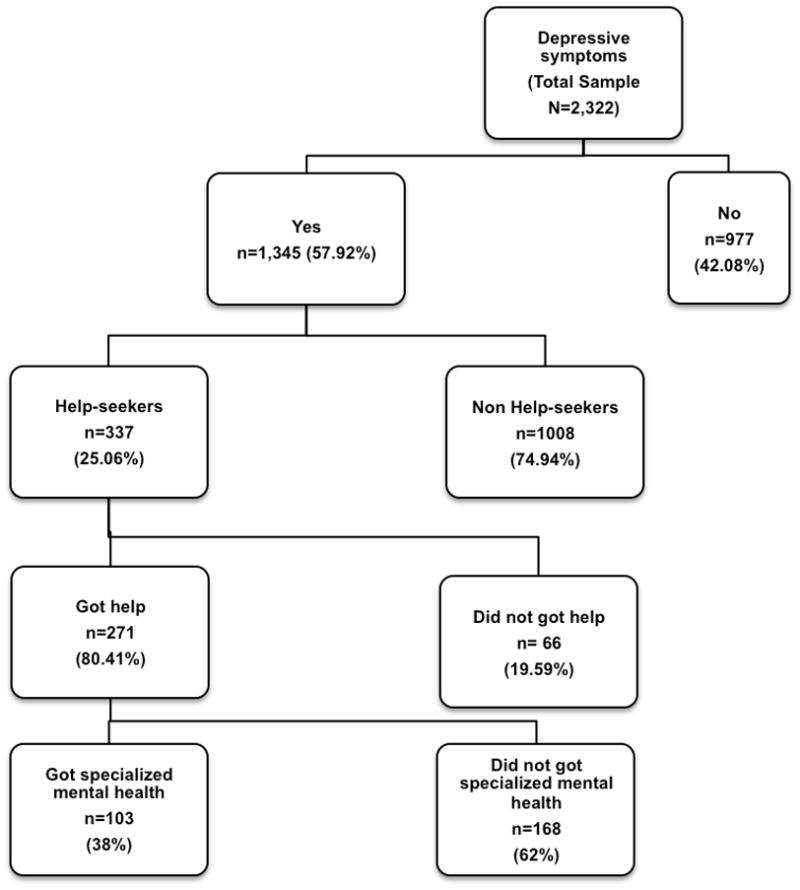

A total of 2,322 individuals were studied; from these, 67.14% (n=1,559) were women, and the mean age was 73.18 years (SD=7.02) 57.9% had symptoms of depression, 337 (25.1%) participants sought help, and 271 (80.4%) received help and 103 (38%) received specialized mental health care. In the stepwise model for not seeking help (χ2=81.66, p<0.0001), significant variables were female gender (OR=0.07 95% CI 0.511–0.958 p=0.026), health care use (OR 3.26 CI 95% 1.64–6.488, p=0.001). Number of years in school, difficulty in activities, SAST score and depression as a disease belief were also significant.

Conclusions

Appropriate mental health care is rather complex and is influenced by several factors. The main factors associated with help seeking were gender, education level, recent health service use, and the belief that depression is not a disease. Detection of subjects with these characteristics could improve care of elderly with depressive symptoms.

Keywords: Mental health services, late life depressive symptoms, help-seeking, late life depression care

Introduction

Depression is one of the more prevalent geriatric syndromes. In a recent review, depressive symptoms were found in 1.6–46% of a geriatric population, mild depression in 1.2–4.7% and moderate to severe depression in 0.86–9.4% of the population (Djernes, 2006). Our group has reported an estimated prevalence of 21.7% (95% CI, 20.4–23) of significant depressive symptoms, with higher proportions in women and the older individuals (García-Peña et al., 2008). It is widely recognized that depression in the elderly is independently associated with multiple adverse outcomes, such as high health services utilization rates, low pharmacological compliance, and synergistic interactions with other comorbidities (Luber et al., 2001; Schoevers et al., 2009; Wagner et al., 2012). Moreover, disability adjusted life years averted by pharmacotherapy (serotonin reuptake inhibitors) and mixed interventions (pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy and proactive management) were found to be cost effective among other non-communicable chronic diseases in Mexico; these findings have a potential global impact on health systems (Salomon et al., 2012). Nevertheless, mental health care or appropriate primary care has been frequently reported to be underutilized in elderly populations (Unutzer, 2007).

To avoid these problems in the elderly, the whole process that leads to optimal caregiving should be considered due to the complex nature of the process and the convergence of several factors, especially in the elderly suffering from depressive symptoms (Evashwick et al., 1984a). This process is composed of help seeking and care, the first factor is imputable to the subject and the second to the health system (Mackenzie et al., 2008). Several conceptual models have been proposed and tested from the early Anderson model to the more recent ones, such as the common sense model (Crabb and Hunsley, 2006a). Help seeking begins with the feeling that something is wrong and the correct interpretation of these perceptions. This interpretation is influenced by beliefs, which in turn are also influenced by other factors, including cognition. The group of beliefs then gives rise to attitudes (positive or negative), and the final part of the process is the execution of actions to receive care (Mackenzie et al., 2006).

Studies about help-seeking in elderly people with depressive symptoms agree on the associations of some positive factors with greater help-seeking behaviors: younger age, female sex, and higher education. Two main approaches have been used to assess these factors, the “hypothetical” approach and the “real-life” approach. Both approaches have produced similar results (Burns et al., 2003; Barney et al., 2006; Mackenzie et al., 2006; Mackenzie et al., 2008; Simning et al., 2010; Crabb and Hunsley, 2006a). The stigma associated with depression has been shown to impact negatively help-seeking behavior. Furthermore, there is some evidence that this stigma might be expressed differently among racial groups (Conner et al., 2010a). Finally, similar factors influencing the search for specialized or general care for depression (Simning et al., 2010).

Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore factors associated with help seeking behaviors in a group of elderly Mexican people with depressive symptoms using a real life approach to explore the reasons given for not seeking help and to assess the proportion of those subjects actually receiving health care (specifically mental health care). In addition, we hypothesized that 1) previous associated factors observed in other studies, such as age, gender, education level, anxiety, and stigma, would have the same associations in our study, 2) comorbidities would influence the help seeking process, and 3) having higher levels of activity and lower levels of dependency regarding activities of daily living would positively influence help seeking behaviors.

Methods

Population

This was a cross-sectional study of the third wave from the cohort: “Integrated Study of Depression Among Elderly Insured by Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (IMSS) in Mexico City”. A detailed description of methods and sampling are described elsewhere (García-Peña et al., 2008). In brief, the population base consisted of all community dwelling subjects 60-year or older who lived in Mexico City and were affiliated to IMSS (N= 384,000; 48% of the whole 60-year or older population of Mexico City). A three-stage cluster sampling procedure, based on Family Medicine Units, drew a probabilistic sample of these affiliates.

Measures

Data were collected from February to September of 2007 using a standardized questionnaire, which was administered through face-to-face interviews at the participant’s home by previously trained personnel and supervised by research assistants. All subjects signed an informed consent document.

The help-seeking process was assessed with two main questions with a time frame of one year: “Have you felt depressed, sad, nervous or worried?” and “Did you seek help?” were asked, with a dichotomous response (yes/no). Those participants who did not seek help were asked about the reasons with nine mutually exclusive questions (see table 3). From there, a sequence of questions were asked to investigate other aspects, including “Did you get help?” and “Did you receive specialized mental health care?” Finally, for those participants who received help, questions about the health care received were asked, including main given diagnoses, type of health service, type of intervention, and adverse drug reactions.

Table 3.

First reasons given for not seeking help (mutually exclusive).

| Number (1,008) | (%) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| I thought the problem would get better by itself | 248 | 24.6 |

| I wanted to handle the problem on my own | 171 | 16.96 |

| I didn’t trust the health professionals | 67 | 6.64 |

| I had transportation problems | 67 | 6.64 |

| I didn’t know where to go | 49 | 4.86 |

| I was worried about health care cost | 47 | 4.66 |

| I didn’t have time to go | 43 | 4.26 |

| I didn’t think treatment would work | 19 | 1.88 |

| I was worried about people’s opinion about me | 9 | 0.89 |

| Other reasons | 273 | 27.08 |

| No reason | 15 | 1.48 |

The collected socio demographic characteristics included age (in years), gender, marital status (married, single, divorced or widowed), education (number of years of school attended), number of people living in the same home of the subject, if the elderly lived alone, and the availability of someone who could take the elderly individual to the doctor. Health self-perception (excellent, very good, good, fair, and poor) and the use of any health service in the last six months were also assessed. Regarding physical activity, two questions from the SF-36 were asked to assess the self-report of limitations to performing vigorous activity (running, lifting heavy objects, playing intense sports) and limitations to performing moderate activity (moving a table, playing moderate sports) with yes/no options. Additional questions on each activity of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) were assessed, and composite variables were created if the subject experienced any difficulty with the ADL or IADL.

Self-report of chronic diseases diagnosed by a doctor were listed for hypertension, diabetes, osteoarthritis, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, osteoporosis, stroke, nephropathy, heart disease, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism and chronic pain, and a sum of each condition was used as a comorbidity index. Depressive symptoms were evaluated with the 30-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) (Yesavage et al., 1982; Sanchez-Garcia et al., 2008). Cognitive impairment was assessed with a previously validated version of the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Reyes de Beaman et al., 2004) and was used as a continuous variable. Anxiety was assessed by means of the Short Anxiety Screening Test (SAST) (Sinoff et al., 1999) as a continuous variable. Depression stigma was assessed with the question “Do you think depression is a disease?” as used in a recent report (Cook and Wang, 2010).

Data Analysis

A descriptive analysis was performed to determine the relative and absolute frequencies or the means and standard deviations. A comparison was made between subjects reporting depressive symptoms and those without depressive symptoms using a t-test for continuous variables and the chi square test for nominal/categorical variables. Absolute and relative frequencies were used to describe the process, including previous health care use, help seeking behavior, help acquisition and the type of help acquired. Absolute and relative frequencies of each of the categories of reasons for not seeking help were also determined.

Help seeking was tested in bivariate analyses using the chi-square test for dichotomous or ordinal variables and the t-test for continuous variables. A first logistic regression was performed in which all explanatory variables were independently entered in the model, both unadjusted and adjusted, reporting odds ratio (with 95% confidence intervals) and p-values. A final model was performed with a stepwise logistic regression, to preserve only significant variables (p<0.05). All calculations were performed with the STATA 12 software (StataCorp LP, Texas).

Ethics statement

The study was reviewed and accepted by the “Comisión Nacional de Investigación Científica de la Coordinación de Investigación en Salud, del Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (National Commission of Scientific Research of the Health Research Commission of the Mexican Social Security Institute), which includes the approval of the Ethics and Methodological sub commissions with the registry number: 2001-785-015. All procedures in this research complied with the Helsinki Declaration; and all subjects signed informed consent. The informed consent procedure was performed by the interviewers, and included a thorough explanation of the study, in the presence of the study subject, and two independent witnesses; emphasizing the absolute freedom of decision in entering and that deciding not to enter would not affect any of the attention given to the subject. Once this was performed, and if the subject accepted, a copy of the explanation given was handed and the study subject, the interviewer and the witnesses signed an original and a copy. Additionally, if the subject during the interview felt that he or she did not want to continue, the interview was stopped with no additional questions, and reassuring that all the care received will be exactly the same.

Results

A total of 2,322 subjects were interviewed, 67.14% (n=1,559) were women, and the mean age was 73.18 years (SD 7.02). The mean GDS score was of 10.9 points (SD 7). A total of 52.8% of participants were married and had a mean time of attending school of 2.2 years. Approximately one in 12 participants lived alone. The most prevalent health problem was hypertension (55.8%), followed by diabetes (30.7%), chronic pain (22.78%), and osteoarthritis (11.4%). The proportion of subjects who indicated that depression is not a disease was 36.04% (n=673). The remaining characteristics of the whole sample are depicted in Table 1.

Table 1.

General characteristics

| Variable | Depressive Symptoms N=1,345 |

No Depressive Symptoms N=977 |

Total N=2,322 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| mean | (SD) | mean | (SD) | mean | (SD) | |

|

|

||||||

| Age in Years | 73.12 | 7.28 | 73.27 | 6.66 | 73.18 | 7.02 |

|

|

||||||

| Gender | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) |

|

|

||||||

| Male | 347 | 25.8 | 416 | 42.5 | 763 | 32.86* |

| Female | 998 | 74.2 | 561 | 57.4 | 1,559 | 67.14* |

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Married | 676 | 50.37 | 551 | 56.3 | 1,227 | 52.8* |

| Single | 74 | 5.5 | 52 | 5.3 | 126 | 5.4* |

| Divorced | 76 | 5.65 | 43 | 4.4 | 119 | 5.1* |

| Widowed | 519 | 38.59 | 331 | 33.8 | 850 | 36.6* |

|

|

||||||

| mean | (SD) | mean | (SD) | mean | (SD) | |

|

|

||||||

| Number of years in school | 2.15 | 1.03 | 2.2 | 1.1 | 2.2 | 1* |

| Number of cohabitants | 3.48 | 3.12 | 3.4 | 3 | 3.4 | 3.1 |

|

|

||||||

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | |

|

|

||||||

| Living alone | 109 | 8.1 | 67 | 6.8 | 176 | 7.5 |

| Health Self-Perception | ||||||

| Excellent | 9 | 0.67 | 21 | 2.1 | 30 | 1.3* |

| Very Good | 16 | 1.19 | 32 | 3.2 | 48 | 2.1* |

| Good | 200 | 14.87 | 316 | 32.3 | 516 | 22.2* |

| Fair | 831 | 61.78 | 528 | 54 | 1359 | 58.5* |

| Poor | 289 | 21.49 | 80 | 8.2 | 369 | 15.9* |

| Health-care use in the last 6 months for any reason | 1243 | 92.56 | 857 | 87.7 | 2102 | 90.5* |

| Someone can take to the doctor | 57 | 4.24 | 20 | 2 | 77 | 3.32* |

| Difficulty in performing vigorous activity | 1181 | 87.81 | 752 | 76.9 | 1933 | 83.2* |

| Difficulty in performing moderate activity | 902 | 67.06 | 479 | 49 | 1381 | 59.4* |

| Difficulty in performing at least one ADL | 397 | 29.5 | 169 | 17.3 | 566 | 24.3* |

| Difficulty in performing at least one IADL | 112 | 8.33 | 175 | 17.9 | 287 | 12.3* |

|

|

||||||

| mean | (SD) | mean | (SD) | mean | (SD) | |

|

|

||||||

| GDS 30 score | 14.22 | 6.51 | 6.3 | 4.72 | 10.9 | 7* |

| SAST score | 21.41 | 5.39 | 15.9 | 3.5 | 19.1 | 5.4* |

| MMSE score | 26.24 | 6.01 | 26.6 | 5.9 | 26.4 | 5.9 |

| Sum of comorbidities | 1.54 | 1.13 | 1.2 | 1.05 | 1.4 | 1.11* |

|

|

||||||

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | |

|

|

||||||

| Hypertension | 804 | 59.77 | 492 | 50.3 | 1296 | 55.8* |

| Diabetes | 425 | 31.59 | 289 | 29.6 | 714 | 30.7* |

| Osteoarthritis | 176 | 13.08 | 90 | 9.2 | 266 | 11.4* |

| Cancer | 42 | 3.12 | 22 | 2.2 | 64 | 2.7 |

| COPD | 57 | 4.23 | 35 | 3.6 | 92 | 3.9 |

| Osteoporosis | 147 | 10.92 | 64 | 6.5 | 211 | 9.1* |

| Stroke | 55 | 4.08 | 12 | 1.2 | 67 | 2.8* |

| Nephropathy | 114 | 8.47 | 45 | 4.6 | 159 | 6.8* |

| Heart Disease | 223 | 16.65 | 109 | 11.1 | 333 | 14.3* |

| Hyperthyroidism | 12 | 0.89 | 6 | 0.6 | 18 | 0.7 |

| Hypothyroidism | 19 | 1.41 | 15 | 3.4 | 34 | 1.4 |

| Pain | 192 | 14.28 | 337 | 34.49 | 529 | 22.78* |

| Indication that depression is not a disease | 442 | 33.01 | 392 | 47 | 673 | 36.04* |

p <0.05

SD= standard deviation, ADL= activities of daily living, IADL=instrumental activities of daily living, GDS=geriatric depression scale, SAST=short anxiety screening test, MMSE=mini-mental status examination, COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

From the total sample, a total of 1,345 (57.92%) reported depressive symptoms in the last year. Those who reported depressive symptoms and sought help had a mean age of 72.33 years (SD 7.05) compared to 73.38 years (SD 7.33) of those who did not seek help (p<0.05). There was a statistically significant difference between the number of male subjects who sought help (21.3%) in comparison with those who did not (27.2%). The mean number of years of school was 2.3 (1.13) for those who sought for help and 2.11 (SD 0.99) for those who did not (p<0.05). Other variables significantly different between groups were use of any health service in the previous six months, means of the GDS 30 and SAST scores, presence of hypertension and mean of comorbidities. Details are presented in Table 2. Finally, 34.82% of non-help-seekers did not believe that depression was an illness, compared to 27% in the other group, and this difference was statistically significant (Table 2).

Table 2.

Differences Between Individuals Seeking Help versus Those Who Did Not Seek Help

| Variable | Did you seek help?

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes N=337 |

No N=1,008 |

Total N=1,345 |

||||

|

| ||||||

| mean | (SD) | mean | (SD) | mean | (SD) | |

|

|

||||||

| Age in Years | 72.33 | 7.05 | 73.38 | 7.33 | 73.12 | 7.28* |

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | |

|

|

||||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 72 | 21.36 | 275 | 27.28 | 347 | 25.8* |

| Female | 265 | 78.63 | 733 | 72.72 | 998 | 74.2 |

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Married | 174 | 26.11 | 502 | 75.67 | 676 | 50.37 |

| Single | 18 | 24.32 | 56 | 74.32 | 74 | 5.5 |

| Divorced | 18 | 25 | 58 | 75 | 76 | 5.65 |

| Widowed | 127 | 24.52 | 392 | 75.5 | 519 | 38.59 |

|

|

||||||

| mean | (SD) | mean | (SD) | mean | (SD) | |

|

|

||||||

| Number of years in school | 2.3 | 1.13 | 2.11 | 0.99 | 2.15 | 1.03* |

| Number of cohabitants | 3.2 | 2.72 | 3.58 | 3.25 | 3.48 | 3.12 |

|

|

||||||

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | |

|

|

||||||

| Living alone | 32 | 9.5 | 77 | 7.64 | 109 | 8.1 |

| Health Self-Perception | ||||||

| Excellent | 1 | 11.11 | 8 | 88.89 | 9 | 0.67 |

| Very Good | 2 | 12.5 | 14 | 87.5 | 16 | 1.19 |

| Good | 48 | 24 | 152 | 76 | 200 | 14.87 |

| Fair | 202 | 24.3 | 629 | 75.7 | 831 | 61.78 |

| Poor | 84 | 29.06 | 205 | 70.94 | 289 | 21.49 |

| Health-care use in the last 6 months for any reason | 327 | 97 | 916 | 90.8 | 1243 | 92.56* |

| Someone can take to the doctor | 16 | 28.07 | 41 | 71.93 | 57 | 4.24 |

| Difficulty in performing vigorous activity | 286 | 24.22 | 895 | 75.78 | 1181 | 87.81 |

| Difficulty in performing moderate activity | 237 | 26.27 | 665 | 73.73 | 902 | 67.06 |

| Difficulty in performing at least one ADL | 104 | 26.2 | 293 | 73.8 | 397 | 29.52 |

| Difficulty in performing at least one IADL | 32 | 28.57 | 80 | 71.43 | 112 | 8.33 |

|

|

||||||

| mean | (SD) | mean | (SD) | mean | (SD) | |

|

|

||||||

| GDS 30 score | 15.35 | 6.4 | 13.86 | 6.5 | 14.22 | 6.51* |

| SAST score | 22.64 | 5.72 | 21.01 | 5.21 | 21.41 | 5.39* |

| MMSE score | 26.47 | 6.23 | 26.17 | 6.02 | 26.24 | 6.01 |

| Sum of comorbidities | 1.67 | 1.13 | 1.5 | 1.13 | 1.54 | 1.13* |

|

|

||||||

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | |

|

|

||||||

| Hypertension | 218 | 27.11 | 586 | 72.89 | 804 | 59.77* |

| Diabetes | 106 | 24.94 | 319 | 75.06 | 425 | 31.59 |

| Osteoarthritis | 44 | 25 | 132 | 75 | 176 | 13.08 |

| Cancer | 14 | 33.33 | 28 | 66.66 | 42 | 3.12 |

| COPD | 17 | 29.82 | 40 | 70.18 | 57 | 4.23 |

| Osteoporosis | 45 | 30.61 | 102 | 69.39 | 147 | 10.92 |

| Stroke | 12 | 21.82 | 43 | 78.18 | 55 | 4.08 |

| Nephropathy | 32 | 28.08 | 82 | 71.92 | 114 | 8.47 |

| Heart Disease | 65 | 29.15 | 158 | 70.85 | 223 | 16.65 |

| Hyperthyroidism | 5 | 41.67 | 7 | 58.33 | 12 | 0.89 |

| Hypothyroidism | 6 | 31.58 | 13 | 68.42 | 19 | 1.41 |

| Pain | 48 | 25 | 144 | 75 | 192 | 14.28 |

| Indication that depression is not a disease | 91 | 27 | 351 | 34.82 | 442 | 33.01* |

p <0.05

SD= standard deviation, ADL= activities of daily living, IADL=instrumental activities of daily living, GDS=geriatric depression scale, SAST=short anxiety screening test, MMSE=mini-mental status examination, COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Table 3 presents the first reason given by subjects for not seeking help, with the most frequent being “I thought the problem would get better by itself” (24.6%) and followed by “I wanted to handle the problem on my own” (16.96%).

Regarding the path (Figure 1) –that begins with the depressive symptomatology and ends when receiving specialized mental health care– only 337 (25.06%) subjects sought help in the first step (help seeking). Following the pathway, 80.41% of the participants obtained help (n=271) and 38% (n=103) obtained specialized mental health. For the total sample of subjects with depressive symptoms (of either help seeking status), only 20.15% received help and 7.65% received specialized mental health-care.

Figure 1.

The first model, which included all the variables, the unadjusted odds ratio (OR) for age were 0.978 (CI 95% 0.96–0.99, p=0.016); and changed to 0.98 (CI 95% CI 0.961–1, p=0.094) when adjusted. Regarding female gender, adjusted OR were of 0.713 (CI 95% 0.51–1.002, p=0.052); and for numbers of years in school in the fully adjusted model OR were 1.06 (CI 95%, 1.03–1.1, p<0.0001) (Table 4). Marital status, as well as those variables related to social support (number of cohabitants, living alone, and having someone that can take the elderly to the doctor), were not significant. Health-care use in the previous six months had an OR of 2.77 (CI 95%, 1.34–5.74, p=0.006) in the fully adjusted model. Difficulties in performing moderate activity and in at least one IADL had an OR of 1.5 and 1.67, respectively, a significant association in the fully adjusted model. On the other hand, difficulty in performing vigorous activity and believing that depression is not an illness were inversely associated with help seeking, with an OR of 0.5 and 0.7, respectively. Comorbidities were statistically significant in the unadjusted model, nevertheless lost significance in the fully adjusted model. In the stepwise model (χ2=81.66, p<0.0001), female gender improved significance (p=0.026) with OR 0.7 (95% CI 0.511–0.958), health care use also had higher OR 3.26 (CI 95% 1.64–6.488, p=0.001. Number of years in school, difficulty in activities, SAST score and depression as a disease belief remained unchanged (Table 5).

Table 4.

Regression models for not seeking help among subjects with significant depressive symptoms.

| Not Adjusted | Fully Adjusted | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| OR (CI95%) | p | OR (CI95%) | p | |||

|

| ||||||

| Age in years | 0.978 | (0.96–0.99) | 0.016 | 0.98 | (0.961–1) | 0.094 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 1.00 | (ref.) | 1.00 | (ref.) | ||

| Female | 0.724 | (0.54–0.972) | 0.032 | 0.713 | (0.51–1.002) | 0.052 |

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Married | 1.00 | (ref.) | - | 1.00 | (ref.) | - |

| Single | 1.01 | (0.583–1.75) | 0.971 | 0.773 | (0.427–1.39) | 0.396 |

| Divorced | 0.974 | (0.563–1.68) | 0.927 | 0.803 | (0.452–1.42) | 0.456 |

| Widowed | 0.945 | (0.725–1.23) | 0.675 | 0.912 | (0.676–1.23) | 0.55 |

| Number of years in school | 1.05 | (1.025–1.08) | < 0.0001 | 1.06 | (1.034–1.1) | < 0.0001 |

| Number of cohabitants | 0.959 | (0.919–1) | 0.055 | 0.969 | (0.925–1.01) | 0.184 |

| Living alone | 0.985 | (0.722–1.34) | 0.925 | 1.164 | (0.698–1.942) | 0.56 |

| Health Self-Perception | ||||||

| Excellent | 1 | (ref.) | - | 1 | (ref.) | - |

| Very Good | 1.142 | (0.08–14.67) | 0.918 | 1.263 | (0.09–17.73) | 0.862 |

| Good | 2.526 | (0.308–20.7) | 0.388 | 2.273 | (0.256–20.16) | 0.461 |

| Fair | 2.56 | (0.319–20.6) | 0.375 | 2.29 | (0.262–20.14) | 0.452 |

| Poor | 3.27 | (0.403–26.6) | 0.267 | 2.383 | (0.266–21.32) | 0.437 |

| Health-care in the last 6 months for any reason | 3.2 | (1.64–6.23) | 0.001 | 2.77 | (1.34–5.74) | 0.006 |

| Someone can take to the doctor | 1.175 | (0.65–2.123) | 0.592 | 0.993 | (0.526–1.87) | 0.985 |

| Difficulty in performing vigorous activity | 0.708 | (0.495–1.01) | 0.058 | 0.505 | (0.321–0.793) | 0.003 |

| Difficulty in performing moderate activity | 1.222 | (0.935–1.59) | 0.141 | 1.5 | (1.045–2.15) | 0.028 |

| Difficulty in performing at least one ADL | 1.08 | (0.833–1.42) | 0.532 | 1.17 | (0.86–1.61) | 0.304 |

| Difficulty in performing at least one IADL | 1.217 | (.791–1.87) | 0.37 | 1.67 | (1.03–2.69) | 0.035 |

| GDS 30 score | 1.036 | (1.016–1.05) | <0.001 | 1.02 | (.991–1.04) | 0.171 |

| SAST score | 1.057 | (1.033–1.08) | <0.001 | 1.055 | (1.019–1.091) | 0.002 |

| MMSE score | 1 | (0.988–1.02) | 0.427 | 1.004 | (0.982–1.02) | 0.709 |

| Sum of comorbidities | 1.137 | (1.022–1.26) | 0.018 | 1.3 | (0.987–1.71) | 0.75 |

| Hypertension | 1.297 | (1.004–1.67) | 0.046 | 1.18 | (0.9–1.54) | 0.213 |

| Diabetes | 0.905 | (0.835–.098) | 0.015 | 1.172 | (0.88–1.55) | 0.271 |

| Osteoarthritis | 0.893 | (0.819–0.97) | 0.01 | 1.283 | (0.871–1.88) | 0.207 |

| Cancer | 0.876 | (0.79–0.961) | 0.005 | 0.831 | (0.436–1.58) | 0.573 |

| COPD | 0.887 | (0.81–0.97) | 0.01 | 1.04 | (0.672–1.6) | 0.858 |

| Osteoporosis | 0.882 | (0.808–0.96) | 0.005 | 0.905 | (0.645–1.27) | 0.567 |

| Stroke | 0.886 | (0.807–0.96) | 0.008 | 1.141 | (0.694–1.87) | 0.602 |

| Nephropathy | 0.882 | (0.807–0.964) | 0.006 | 1.043 | (0.664–1.63) | 0.852 |

| Heart Disease | 0.88 | (.807–.96) | 0.004 | 0.934 | (0.662–1.31) | 0.662 |

| Hyperthyroidism | 0.876 | (0.799–0.96) | 0.006 | 0.887 | (0.337–2.32) | 0.337 |

| Hypothyroidism | 0.875 | (0.798–0.96) | 0.005 | 0.809 | (0.413–1.58) | 0.538 |

| Pain | 0.968 | (0.753–1.24) | 0.803 | 1.365 | (0.918–.2.02) | 0.124 |

| Indication that depression is not a disease | 0.701 | (0.533–0.922) | 0.011 | 0.719 | (0.414–0.959) | 0.025 |

GDS=geriatric depression scale, SAST=short anxiety screening test.

Table 5.

Final logistic regression (stepwise) model for not seeking help among subjects with significant depressive symptoms.

| Variable | OR (CI 95%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 1.00 | (ref.) | |

| Female | 0.7 | (0.511–0.958) | 0.026 |

| Number of years in school | 1.065 | (1.04–1.104) | < 0.0001 |

| Health-care in the last 6 months for any reason | 3.26 | (1.64–6.488) | 0.001 |

| Difficulty in performing vigorous activity | 0.484 | (0.311–0.753) | 0.001 |

| Difficulty in performing moderate activity | 1.458 | (1.04–2.043) | 0.028 |

| Difficulty in performing at least one IADL | 1.6 | (1.004–2.563) | 0.048 |

| SAST score | 1.072 | (1.045–1.1) | < 0.001 |

| Indication that depression is not a disease | 0.715 | (0.539–0.948) | 0.02 |

Finally, the variables associated with receiving help and specialized mental-health care were education (OR=1.07, CI95% 1.02–1.13, p=0.008) and having a limitation in performing vigorous physical activity (OR=2.48, CI95% 1.14–5.36, p=0.021); these variables remained constant in the logistic regression model.

For those who received help, 68.5% (n=227) received a depression diagnosis; other given diagnoses were anxiety (14.91%), bereavement (5.61%), insomnia and nervousness (both 6.7%). Pharmacotherapy was initiated for 78.15% of those who received help, and benzodiazepines (diazepam and clonazepam) and imipramine were the drugs most frequently prescribed; the frequency of side effects was over 60% (i.e., sleepiness, insomnia, nausea). Other interventions included psychotherapy (24%), alternative medicine (9.05%) and multivitamin supplements (10.23%). Approximately 104 subjects consulted a private practitioner (30.32%).

Discussion

The main factors associated with help seeking in this population were gender, education level, recent health service use, and the belief that depression is not a disease; all of these factors have been reported previously (Crabb and Hunsley, 2006b; Conner et al., 2010b). In addition, difficulty in performing activities and IADL were also associated with help seeking behavior, which agrees with the previous factors reported by Evashwick and colleagues in the context of the Andersen’s model of health services utilization (Evashwick et al., 1984b). There were associations between comorbidities and help seeking, but the associations were no longer significant in the fully adjusted model for either individual diseases or the sum of them. This result may be due in part to the adjustment for recent health care use, which is more common in those subjects who receive constant care due to a particular disease or diseases.

Only a small proportion of subjects with depressive symptoms obtained appropriate mental health care, as shown by 7.65% of those who responded affirmatively to the depression question either because they did not seek help, did not receive help or did not have specialized mental health treatment. The factors associated with each of these filters were different, pointing to the fact that different strategies should be used during these steps to develop an appropriate and targeted intervention for elderly individuals with depressive symptoms. The main reasons for not seeking help were similar to those reported by Garrido et al. in non-Hispanics, particularly the thoughts indicating a low health literacy, such as believing that depressive symptoms would get better by themselves, that problems are easy to handle and thinking that treatment would not work (Garrido et al., 2011). One of the main reasons for not seeking help in our study was “I thought the problem would get better by itself”, which was reported in 24.6% of participants; this finding was already reported in the general population in which depression stigma leads the individual to consider this state as normal or as transitory (Wittkampf et al., 2008). This result can also point to the lack of recognition of one’s own symptoms, something that has a close relationship with health literacy. The same behavior was reported by Lexis, in which a group of workers were screened for depressive symptoms and help seeking behavior (Lexis et al., 2010). It is also relevant to note the scarce proportion of subjects with depressive symptoms that received help because depression has been shown as the first cause of lost healthy life years in Mexico (>10%) (Gómez Dantés et al., 2011).

There is evidence of a higher use of somatic services (Garcia-Pena et al., 2008) and both a lower referral to a suitable specialty (i.e., psychiatry or geriatrics) (Beekman et al., 2002; Roelands et al., 2003) and an under-utilization of mental services in the elderly with depressive symptoms. These findings are similar to data presented in this report (low use of mental health services and high use of benzodiazepines) (Jorm et al., 2000; Valenstein et al., 2004). Moreover, we found that depressed elderly individuals who were functionally impaired (who experienced difficulties in performing physical activity) were less likely to receive help.

To reduce disease burden, comprehensive interventional strategies including primary and secondary prevention, diagnosis and treatment are needed (Alexopoulos and Bruce, 2009). However, subjects with depression are reluctant to seek professional help, with estimates indicating that over half of those with major depression in the community do not seek help. In the present study, approximately 75% of the participants did not seek help. This reluctance is enhanced when seeking care from a specialized mental health professional (Burns et al., 2003). One of the main recognized reasons is the stigma associated with mental illness, which may negatively affect individuals’ willingness to seek help (Barney et al., 2006). Although this stigma was not studied in these subjects, it may account for the proportion of elderly people who did not seek help and may be reflected in some of the responses regarding the reasons for not seeking help (i.e., “I was worried about people’s opinion about me”). Wang and Lai in 2008 reported gender as a significant factor associated with depression stigma. This finding was consistent with previous research indicating that men had held higher stigmatizing attitudes and most likely sought help less frequently than women (Wang and Lai, 2008). There was a significant independent association between genders in our study, favoring positive help-seeking behavior in males; this result differs from other reports and reflects a cultural influence towards protecting males. In addition, this association was only observed in the stepwise model, which could reflect a type I error. Stigma has been described in those groups with lower educational levels because years in school were associated independently with seeking help (Cook and Wang, 2010); this finding was confirmed in the present study. However, our sample was biased regarding scholarship because clients of our health system are reported to have lower scholarship in comparison to the general population.

Another important issue is the lack of training for the first level of care for treating mental health diseases. Family doctors must be capable of treating mild and moderate symptoms of depression in the elderly, and pharmacological resources must be available (Wang et al., 2009). Additionally, nurses who are well-trained in mental health can manage group therapies, as demonstrated by Muñoz et al. (Munoz and Mendelson, 2005). Unfortunately, only a small fraction in our sample received care. The vast majority were prescribed benzodiazepines (diazepam and clonazepam), and the antidepressant that was reported as most prescribed is well recognized for its anticholinergic side effects (Fick et al., 2003).

One of the strengths of our study is the demonstration that the so-called filter pathway is a useful approach to assess the help seeking process. The health care use filter was particularly helpful, as shown by a two times greater probability of seeking help if any health service was used in the previous six months.

Limitations of the study included a possible effect of memory bias as the elderly individual or their caregiver transmitted the data orally; however, this method is the typical way to collect information in this type of study. Although depressive symptoms were assessed with a sole question, a single question for assessing depression in elderly has been reported to have a sensitivity of 50 to 100% and a specificity of 82.9 to 98.6% compared with structured interviews or other screening tools (Ayalon et al., 2010). In addition, our sample subjects belong to an specific health system in Mexico, that could not reflect the whole population. Finally, some other factors were not tested in this study such as those related to the surrounding environment, which could influence the seeking process.

Future research should consider other characteristics of subjects with depressive symptoms who do not seek help or do not receive help, particularly regarding the outcomes. In addition, the healthcare and social services utilization of elderly people with mental disorders, especially depressive symptoms, has not been sufficiently studied. Greater knowledge in this area could provide direction for preventive and curative interventions. We agree with Conner and colleagues that strategies should be implemented and tested to avoid the barriers preventing help seeking behaviors and to allow for appropriate care to be administered.

Key points.

Help-seeking behaviors in elderly are complex and multifactorial.

Depressive symptoms make more difficult this process.

There are cultural differences regarding help-seeking process.

Knowing the factors that impact help-seeking process in elderly with depressive symptoms could aid in an appropriate mental health care.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding:

This project was supported by grants from CONACyT (México) 2002-CO1-6868, Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS 2002-382), and NIH-FIRCA R03 TW005888. Dr. Wagner was funded through grant DA 17796-01 from NIDA and P60-MD002217-01 from the NCMHHD.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None

Authors’ contributions

CGP designed the study and the original question and contributed to the analysis. MUPZ assisted with the design and the analysis and prepared the draft. VEAL contributed to the conception of the study and conducted the analysis, interpreted the data and reviewed the manuscript. FW and JJG were involved in the design of the study, the interpretation of the data and the revision of the manuscript. All authors gave final approval of the submitted version

References

- Alexopoulos GS, Bruce ML. A model for intervention research in late-life depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24:1325–34. doi: 10.1002/gps.2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayalon L, Goldfracht M, Bech P. ‘Do you think you suffer from depression?’ Reevaluating the use of a single item question for the screening of depression in older primary care patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25:497–502. doi: 10.1002/gps.2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barney LJ, Griffiths KM, Jorm AF, Christensen H. Stigma about depression and its impact on help-seeking intentions. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40:51–4. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beekman AT, Penninx BW, Deeg DJ, de Beurs E, Geerling SW, van Tilburg W. The impact of depression on the well-being, disability and use of services in older adults: a longitudinal perspective. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2002;105:20–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.10078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns T, Eichenberger A, Eich D, Ajdacic-Gross V, Angst J, Rossler W. Which individuals with affective symptoms seek help? Results from the Zurich epidemiological study. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2003;108:419–26. doi: 10.1046/j.0001-690x.2003.00207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner KO, Copeland VC, Grote NK, Koeske G, Rosen D, Reynolds CF, Brown C. Mental health treatment seeking among older adults with depression: the impact of stigma and race. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010a;18:531–43. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181cc0366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner KO, Copeland VC, Grote NK, Rosen D, Albert S, McMurray ML, Reynolds CF, Brown C, Koeske G. Barriers to treatment and culturally endorsed coping strategies among depressed African-American older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2010b;14:971–83. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2010.501061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook TM, Wang J. Descriptive epidemiology of stigma against depression in a general population sample in Alberta. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:29. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabb R, Hunsley J. Utilization of mental health care services among older adults with depression. J Clin Psychol. 2006a;62:299–312. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabb R, Hunsley J. Utilization of mental health care services among older adults with depression. J Clin Psychol. 2006b;62:299–312. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djernes JK. Prevalence and predictors of depression in populations of elderly: a review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113:372–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evashwick C, Rowe G, Diehr P, Branch L. Factors explaining the use of health care services by the elderly. Health Serv Res. 1984a;19:357–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evashwick C, Rowe G, Diehr P, Branch L. Factors explaining the use of health care services by the elderly. Health Serv Res. 1984b;19:357–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fick DM, Cooper JW, Wade WE, Waller JL, Maclean JR, Beers MH. Updating the Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults: results of a US consensus panel of experts. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2716–24. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.22.2716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Pena C, Wagner FA, Sanchez-Garcia S, Juarez-Cedillo T, Espinel-Bermudez C, Garcia-Gonzalez JJ, Gallegos-Carrillo K, Franco-Marina F, Gallo JJ. Depressive symptoms among older adults in Mexico City. Journal of general internal medicine. 2008;23:1973–80. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0799-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Peña C, Wagner FA, Sánchez-Garcia S, Juárez-Cedillo T, Espinel-Bermúdez C, García-Gonzalez JJ, Gallegos-Carrillo K, Franco-Marina F, Gallo JJ. Depressive symptoms among older adults in Mexico City. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1973–80. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0799-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido MM, Kane RL, Kaas M, Kane RA. Use of mental health care by community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:50–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03220.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Dantés H, Castro MV, Franco-Marina F, Bedregal P, Rodríguez García J, Espinoza A, Valdez Huarcaya W, Lozano R, América RdIsCdEdOdSIp. Burden of disease in Latin America. Salud Publica Mex. 2011;53(Suppl 2):s72–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF, Grayson D, Creasey H, Waite L, Broe GA. Long-term benzodiazepine use by elderly people living in the community. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2000;24:7–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2000.tb00715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lexis MA, Jansen NW, Stevens FC, van Amelsvoort LG, Kant I. Experience of health complaints and help seeking behavior in employees screened for depressive complaints and risk of future sickness absence. J Occup Rehabil. 2010;20:537–46. doi: 10.1007/s10926-010-9244-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luber MP, Meyers BS, Williams-Russo PG, Hollenberg JP, DiDomenico TN, Charlson ME, Alexopoulos GS. Depression and service utilization in elderly primary care patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9:169–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie CS, Gekoski WL, Knox VJ. Age, gender, and the underutilization of mental health services: the influence of help-seeking attitudes. Aging Ment Health. 2006;10:574–82. doi: 10.1080/13607860600641200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie CS, Scott T, Mather A, Sareen J. Older adults’ help-seeking attitudes and treatment beliefs concerning mental health problems. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16:1010–9. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31818cd3be. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz RF, Mendelson T. Toward evidence-based interventions for diverse populations: The San Francisco General Hospital prevention and treatment manuals. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:790–9. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes de Beaman S, Beaman P, Garcia-Pena C, Villa A, Heres J, Cordova A, Jagger C. Validation of a modified version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) in Spanish. Aging Neuropsychology Cognition. 2004;11:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Roelands M, Van Oyen H, Depoorter A, Baro F, Van Oost P. Are cognitive impairment and depressive mood associated with increased service utilisation in community-dwelling elderly people? Health Soc Care Community. 2003;11:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon JA, Carvalho N, Gutirrez-Delgado C, Orozco R, Mancuso A, Hogan DR, Lee D, Murakami Y, Sridharan L, Medina-Mora ME, González-Pier E. Intervention strategies to reduce the burden of non-communicable diseases in Mexico: cost effectiveness analysis. Bmj. 2012;344:e355. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Garcia S, Juarez-Cedillo T, Garcia-Gonzalez JJ, Espinel-Bermudez C, Gallo JJ, Wagner FA, Vazquez-Estupinan F, Garcia-Pena C. Usefulness of two instruments in assessing depression among elderly Mexicans in population studies and for primary care. Salud Publica Mex. 2008;50:447–56. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342008000600005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoevers RA, Geerlings MI, Deeg DJ, Holwerda TJ, Jonker C, Beekman AT. Depression and excess mortality: evidence for a dose response relation in community living elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24:169–76. doi: 10.1002/gps.2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simning A, Richardson TM, Friedman B, Boyle LL, Podgorski C, Conwell Y. Mental distress and service utilization among help-seeking, community-dwelling older adults. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22:739–49. doi: 10.1017/S104161021000058X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinoff G, Ore L, Zlotogorsky D, Tamir A. Short Anxiety Screening Test--a brief instrument for detecting anxiety in the elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999;14:1062–71. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(199912)14:12<1062::aid-gps67>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unutzer J. Clinical practice. Late-life depression. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2269–76. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp073754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenstein M, Taylor KK, Austin K, Kales HC, McCarthy JF, Blow FC. Benzodiazepine use among depressed patients treated in mental health settings. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:654–61. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner F, Gonzalez-Gonzalez C, Sanchez-Garcia S, Carmen Garcia-Pena C, Gallo J. Salud Mental. 2012. Enfocando la depresión como un problema de salud pública en México. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Lai D. The relationship between mental health literacy, personal contacts and personal stigma against depression. J Affect Disord. 2008;110:191–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Browne DC, Petras H, Stuart EA, Wagner FA, Lambert SF, Kellam SG, Ialongo NS. Depressed mood and the effect of two universal first grade preventive interventions on survival to the first tobacco cigarette smoked among urban youth. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;100:194–203. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittkampf KA, van Zwieten M, Smits FT, Schene AH, Huyser J, van Weert HC. Patients’ view on screening for depression in general practice. Fam Pract. 2008;25:438–44. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, Leirer VO. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982;17:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]