Abstract

Endogenous signals originating at the site of injury are involved in the paracrine recruitment, proliferation, and differentiation of circulating progenitor and diverse inflammatory cell types. Here, we investigate a strategy to exploit endogenous cell recruitment mechanisms to regenerate injured bone by local targeting and activation of sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) receptors. A mandibular defect model was selected for evaluating regeneration of bone following trauma or congenital disease. The particular challenges of mandibular reconstruction are inherent in the complex anatomy and function of the bone given that the area is highly vascularized and in close proximity to muscle. Nanofibers composed of poly(DL-lactide-co-glycolide) (PLAGA) and polycaprolactone (PCL) were used to delivery FTY720, a targeted agonist of S1P receptors 1 and 3. In vitro culture of bone progenitor cells on drug loaded constructs significantly enhanced SDF1α mediated chemotaxis of bone marrow mononuclear cells. In vivo results show that local delivery of FTY720 from composite nanofibers enhanced blood vessel ingrowth and increased recruitment of M2 alternatively activated macrophages, leading to significant osseous tissue ingrowth into critical sized defects after 12 weeks of treatment. These results demonstrate that local activation of S1P receptors is a regenerative cue resulting in recruitment of wound healing or anti-inflammatory macrophages and bone healing. Use of such small molecule therapy can provide an alternative to biological factors for the clinical treatment of critical size craniofacial defects.

Keywords: Craniofacial Reconstruction, S1P, FTY720, Neovascularization, Bone Healing

INTRODUCTION

Mandibular bone regeneration is a major challenge for reconstructive surgeons treating patients with cancer of the mouth or neck, trauma-related injury, or congenital disease. Rapid reconstruction is necessary in order to quickly restore essential functions such as breathing, chewing, and swallowing, as well as cosmetic facial appearance. Ideally, mandibular reconstruction is permanent so that patients’ quality of life is minimally impacted and costs associated with multiple hospitalizations are reduced. The most common reconstructive techniques include free tissue transfer, non-vascularized autologous or allogeneic bone grafting, and inert artificial implants. However, the risk of complications is significant, with estimates of one-year success rate as low as 66% in patients receiving titanium reconstruction plates and only 63% in patients receiving free autologous bone grafts. Six-month success rate of reconstructive plates is only 32.2%, with complications including extra-oral and intraoral exposure, loose screws, and plate fractures1 occurring in as many as 39% of patients [1,2]. Consequently, free tissue transfer remains the gold standard, but alternative therapies are needed to avoid associated complications and improve clinical outcome of mandibular reconstruction.

Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) in the TGF-β superfamily of differentiation factors have received attention as an alternative or adjuvant to current strategies. rhBMP-2-loaded polylactic acid discs were found to be capable of bridging rat critical size mandibular defects [3], while rhBMP-2 loaded into hydroxyapatite and β-tricalcium phosphate improved bone healing outcome in primates compared to rhBMP-2-loaded collagen sponges [4]. Clinically, rhBMP-2 was FDA-approved for use in open tibia fractures in 2004 and in 2007 as an alternative to autogenous bone grafting in sinus augmentations. Off-label usage of rhBMP-2 in mandibular reconstruction has successfully been reported in several clinical case studies [5,6]. Unfortunately, the use of rhBMP-2 has not been widely adopted due to high costs, short shelf life, and skepticism regarding the supra-physiological delivery dose [7].

Recently, our group has sought to circumvent the clinical challenges presented by growth factors and protein-based therapies by investigating the use of small molecules as bone repair therapeutics. We have focused particularly on the role of sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), a bioactive signaling lipid, in harnessing endogenous repair mechanisms to promote neovascularization and tissue regeneration in cranial and long bone critical size defect models. S1P signaling is involved in determination of macrophage phenotype [8]; specifically, exogenous delivery of S1P promotes macrophages to adopt an M2-like phenotype instead of a classically-activated, pro-inflammatory M1-like phenotype [9]. Moreover, S1P signaling has been implicated in osteoblastogenesis [10], vessel stabilization and maturation [11], and trafficking of progenitor cell types [12,13]. FTY720, a stable analog of S1P, also promotes microvascular remodeling through activation of S1P receptors 1 and 3 [14] by enhancing the recruitment and proliferation of mural progenitor cells [15], indicating that S1P signaling may induce secretion of chemotactic agents. Enhanced recruitment of anti-inflammatory cell types such as alternatively activated M2-like macrophages may promote vascularization, wound healing and tissue regeneration [16]. Taken together, this lead us to investigate the ability of the S1P synthetic analog FTY720 to locally condition injured tissues for regeneration in a mandibular bone defect model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of nanofibers

Nanofibers were made from polycaprolactone (PCL; Sigma, USA) and poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLAGA, Lakeshore Biomaterials, Birmingham, AL). Briefly, they were combined in a 1:1 (w/w) ratio and then dissolved in 3:1 (v/v) chloroform methanol. The final concentration of polymer solution was 18% (w/v). The solution was agitated until the polymer dissolved and then loaded into a 3mL rubber-free syringe. Electrospinning was performed at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/hour, an applied voltage of 19 kV, and a working distance of 10 cm. Nanofibers were collected on a stationary aluminum plate and then stored in a desiccator until use. To make drug-loaded nanofibers, FTY720 (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) was dissolved in 3:1 chloroform methanol solution and 1:1 PCL/PLAGA was added at a concentration of 20% (w/v). The final drug:polymer ratio was 1:200 (w/w). Electrospinning was performed at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/hour, an applied voltage of 19 kV, and a working distance of 15 cm in order to form nanofibers of similar morphology to unloaded nanofibers. Both unloaded and FTY720-loaded nanofibers were cut into disks with a 6mm biopsy punch.

Characterization of nanofibers

Characterization of nanofiber diameter and morphology was performed using a JEOL 6400 scanning electron microscope (SEM) with Orion image processing. Samples were coated with gold and then imaged at a working distance of 39–43 mm and an accelerating voltage of 15 kV. Diameter was assessed using ImageJ (NIH, USA). Contact angle measurements were made by placing a drop of glycerin on the nanofiber surface mounted on the stage of a goniometer (Rame-Hart Standard Contact Angle Goniometer, Model 200; Rame-Hart Instrument Co., Succasunna, NJ). DROPimage Standard software was used to measure the contact angle between the nanofibers and the liquid. At least 3 images were quantified and averaged. The release of FTY720 from drug-loaded, polymer nanofibers was measured using HPLC-MS. Scaffolds were incubated in simulated body fluid (pH 7.2; 7.996 g NaCl, 0.35 g NaHCO3, 0.3 g KCl, 0.278 g CaCl2, 0.136 g KH2PO4, 0.095 g MgCl2, 0.06 g MgSO4 in 1 L deionized water) with 4% (w:v) fatty acid free bovine serum albumin (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) and maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2. At designated time points, the surrounding solution was removed for analysis and replaced. Sphingolipid extraction was performed as previously described [17]. HPLC-MS was performed using a Shimadzu UFLC High Performance Liquid Chromatograph (Columbia, MD, USA) in combination with a Supelco Discovery C18, 5 μm (125×2 mm) and an ABI 4000 QTrap triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, USA).

Mouse Dorsal Skinfold Window Chamber Model

All surgeries were performed according to a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee at the University of Virginia. 10 C57BL/6J male mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) were randomly assigned to a nanofibers (n=6) or FTY720-loaded nanofibers (n=4) treatment group. Anesthesia was induced with isoflurane gas (2–3%) and the surgical plane was maintained throughout the procedure with a nose cone (1–2%) equipped with a scavenging apparatus. Dorsal skinfold window chambers were implanted as previously described14. Briefly, dorsal skin was attached to a corkboard with 26 gauge needles and the top layer of skin corresponding with the window portion of the chamber (10mm diameter) was removed to expose the cutaneous microcirculation of the panniculus carnosus. Ringers solution was added throughout the process to keep the area hydrated. The top titanium chamber was secured with sutures and the screws were tightened to secure the chamber. Ringers solution was used to fill the cavity before implanting 6 mm diameter nanofiber scaffolds and applying a glass coverslip. Following surgical closure, animals were provided with post-operative analgesics and antibiotics for one week.

Light microscopy (Nikon, Melville, NY) images were taken on Days 0 and 7 after surgery with a 4X objective and then montaged for analysis. Blood vessels were traced by hand using a brush tool in Photoshop (CS5) and the traced images were analyzed using ImageJ. Thresholding, binary, and skeletonization modifications were applied to the image so that the total length of blood vessels for each animal could be measured. Vessel diameters in pixels (measured on the full color images in ImageJ) were compared to the day 0 measurements to obtain a percent change. Tissue specimens were embedded after 7 days and stained for hematoxylin and eosin as described later.

Mouse Implant Model to Evaluate Local Inflammatory Reaction

Four BALB/C mice were prepared and anesthetized as described in the previous section. Two incisions were made near the scapulae on the dorsal of the mice. Each mouse received an unloaded nanofibers implant and a FTY720-loaded nanofibers implant. Implants were inserted into distinct subcutaneous pockets extending away from the spine of the mouse. Both incisions were sutured and mice were given Bupronex (0.03cc) subcutaneously upon waking. After 12 hours of free access to food and water, the mice were sacrificed using CO2 affixation and the dorsal tissue was harvested. The tissue was cut into 2–3 mm size pieces, and then digested with collagenase P (1mg/mL) to create a single cell suspension.

This prepared cell suspension was stained with the following monoclonal antibodies: APC-Cy7 CD4 (Biolegend, San Diego, CA), PE F4/80 (Biolegend, San Diego, CA), APC CD36 (Biolegend, San Diego, CA), PerCP-Cy5.5 Ly6C (ebioscience, San Diego, CA), biotin CD206 (Serotec, Raleigh, NC), and streptavidin Pacific Orange™ conjugate (Invitrogen Life Technologies, USA). Following staining, cells were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 30 min. Cells were then stored in 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen Life Technologies, USA) (FBS) until flow cytometry was performed according to standard procedures and analyzed on a Beckman-Coulter CyAn ADP LX (Brea, California, USA) at the UVA Flow Cytometery Core.

Migration assay

The ability of FTY720 treated bone marrow derived mononuclear cells (BMNCs) to respond to cytokines such as SDF-1α was evaluated using a transwell migration assay. Lysed BMNCs were collected from the tibia of Sprague Daley rats (8–12 weeks, Charles River), serum starved for 2 hours and then pre-treated with either serum free media (SFM) or 10 ng/ml FTY720 (Cayman, USA) for 30 minutes. They were then re-suspended in serum free Dulbecco’s Modification of Eagles Medium (DMEM low glucose, Invitrogen Life Technologies, USA) and added to the top of a transwell chamber containing a 5μm pore size filter (Corning, Corning, NY, USA). The bottom of the wells contained SFM or 100 ng/mL SDF-1 α (ProspecBio, USA) in DMEM. The cells were incubated at 37°C for 4 hours, and then the number of cells that migrated through was counted. The cells that migrated towards SDF-1α were collected from the bottom of the plate and treated with monoclonal antibodies to CD45, CD11b and CD90 for flow cytometry analysis according to standard procedures on a 9 color CyAn flow cytometer.

The ability of unloaded and FTY720-loaded nanofibers to recruit bone marrow-derived progenitor and inflammatory cells was then assessed using a similar assay. Progenitor populations were harvested from the vascular stromal fraction of epididymal fat pads of Sprague Dawley female rats (8–12 weeks old). Adipose tissue was digested with collagenase type-1 (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA), rinsed with PBS, and then centrifuged, leaving the stromal vascular fraction. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) were then cultured up to passage three in complete stromal media composed of DMEM + Ham’s F12 (DMEM-Ham’s F12, Invitrogen Life Technologies, USA), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen Life Technologies, USA), 10% FBS and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2. Media was changed every 3 days and cells were passaged upon 70% confluency. Progenitors were identified by flow cytometry. MSCs were washed in PBS, trypsinized, and stained for 1 h at 4°C using CD11b (Invitrogen Life Technologies, USA), CD45 (Invitrogen Life Technologies, USA), and CD90 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). Following staining, cells were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 30 min. Cells were then stored in 10% FBS until flow cytometry was performed on a Beckman-Coulter CyAn ADP LX (Brea, California, USA) at the UVA Flow Cytometery Core.

For the migration assay, conditioned media (CM) was generated by combining SFM with four conditions: (1) unloaded nanofibers, (2) FTY720-loaded nanofibers, (3) MSCs cultured on unloaded nanofibers, and (4) MSCs cultured on FTY720-loaded nanofibers. CM was placed in the bottom well of a 24-well plate with or without 100 ng/mL SDF-1α. Lysed BMNCs harvested from Sprague Dawley female rats (8–12 weeks old) were placed in the upper well of a transwell chamber containing a 5μm pore size filter (Corning, Corning, NY, USA). The cells that migrated through the filter into the bottom well were counted and expressed as a percentage of cells migrated and then normalized to the percentage of cells that migrated to SFM.

Rat mandibular defect model

All surgeries were performed according to a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee at the University of Virginia. Mandibular defect experiments were carried out using Sprague Dawley rats (9 weeks old) from Charles River (Wilmington, MA, USA). Rats were administered Xylazine-Ketamine cocktail via I.P. injection (80/8 mg/kg IP). The skin overlying the right mandible was then trimmed of hair and sterilized with betadine solution. Full thickness critical size mandibular defects (5mm) were created in the ramus of the right mandibles of 21 animals. Animals were then randomly assigned to three experimental treatment groups: (1) no treatment, (2) treatment with unloaded PCL/PLAGA nanofibers, and (3) treatment with FTY720-loaded PCL/PLAGA nanofibers (n=7). For animals receiving nanofiber implants (unloaded or FTY720-loaded), two nanofiber disks were placed in the defect area to provide mechanical support and enhance drug dose. Following surgical closure, animals were provided with post-operative analgesics and antibiotics for one week.

Microcomputed imaging analysis of mandibular defect

Rats were imaged using a quantitative micro-computed tomography (microCT) vivaCT40 scanner (SCANCO Medical, Bruttisellen, Switzerland) at the following parameters: 38 μm voxel size, 55 kVp, 145 μA, medium resolution, 38.9 mm diameter field of view, and 200 ms integration time (73 mGy radiation per scan). MicroCT was performed at weeks 0, 3, 5, 7, 10, and 12. Two-dimensional slices were reconstructed and two-dimensional quantification was performed using ImageJ analysis software. An appropriate threshold was applied to all images and they were then converted to binary. Contour lines were drawn that approximated a circular defect 5 mm in diameter. The area inside the contour was measured for each time point in ImageJ and expressed as change in bone area compared to week 0.

After week 12 microCT scans, three rats in each group were sacrificed for assessment of vascularization in the defect area using Microfil enhanced imaging. The common carotid arteries were cannulated in order to directly perfuse into the vasculature of the head and neck. First, animals were perfused with 10mL of 2% heparin-saline on both sides at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min. Animals were then perfused with 3 mL of MICROFILR MV-122 (Flow Tech, Carver, MA, USA) at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min. Perfused animals were stored at 4°C for 16 h and then the defect area was harvested, fixed, and decalcified. Samples were scanned with microCT at the following parameters: 21 μm voxel size, 45 kVp, 177 μA, high resolution, 21.5 mm diameter field of view, and 200 ms integration time. Blood vessels in decalcified tissue were thresholded from 264–1500 mg HA/cm3. Blood vessels were traced and then analyzed using ImageJ. This was done by applying binary and skeletonization modifications to the image and the total length of blood vessels for each animal was recorded. Vessel diameters were collected by hand measurements made on the electronic image. After microCT scans, the mandible was harvested and prepared for histological assessment as described below.

Histological sectioning and staining

The ramus surrounding the defect area were placed in 10% buffered formalin for one week to allow fixation and placed in HCl and EDTA decalcifying solution (Richard-Allan Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI, USA) for 3 days at 4°C. They were then stored in 70% ethanol until embedding in paraffin. Soft tissue samples from the backpack model were embedded directly after fixation. Sections were stained for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and/or Masson’s trichrome for cellular histomorphometry analysis at the UVA Histology Core. Bone sections were dewaxed for immunohistochemical analysis using xylene, ethanol, and DI water. CCR7 (Epitomics, Burlingame, CA) and CD163 (Serotec, Raleigh, NC) staining was done in the UVA Tissue Biorepository Core to assess M1 and M2 macrophage presence respectively.

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis of the increase in bone and blood vessel volume was performed using ANOVA, followed by post hoc Tukey’s Test for pairwise comparison. One-way ANOVA analysis was done for migration and flow cytometry analysis. Grubb’s test was used for outlier analysis.

RESULTS

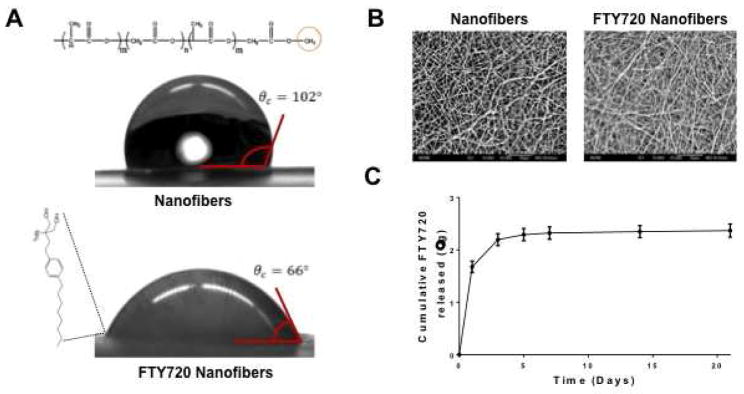

Characterization of FTY720-loaded nanofibers

Addition of FTY720 to PCL/PLAGA nanofibers resulted in minor changes in nanofiber morphology, although overall features were preserved as demonstrated in scanning electron micrographs (Fig 1B). The diameter increased from an average of 320 nm to 375 nm when FTY720 was incorporated and the curvature of the nanofibers appeared to decrease. Changes in surface chemistry were assessed by measuring the contact angle in glycerin droplet experiments (Fig 1A). Nanofibers containing FTY720 have reduced hydrophobicity, as demonstrated by the smaller contact angle between nanofibers and glycerin droplet. We have previously demonstrated sustained release of FTY720 from PLAGA films and microspheres15, as well as PLAGA-coated bone allografts [17]. However, this is the first time that FTY720 has been encapsulated and therapeutically delivered in nanofibers to treat bone defects. The release profile of FTY720 from PCL/PLAGA nanofibers was measured by removing and replacing the supernatant from loaded nanofibers incubated in BSA-containing simulated body fluid. Samples were then analyzed for FTY720 content using HPLC-MS. Quantification of cumulative drug release demonstrates that an initial burst of FTY720 occurs during days 0 to 5, while sustained release occurs up to at least 21 days (Fig 1C). The characteristic initial burst represents release of superficially associated FTY720, while sustained release indicates liberation of encapsulated drug during polymer degradation.

Fig 1.

Characterization of FTY720 loading in PCL/PLAGA nanofibers at a drug:polymer ratio of 1:200 by weight. (A) Glycerine drop contact angle analysis demonstrates that unloaded nanofibers are more hydrophobic than FTY720 loaded nanofibers. (B) Scanning electron micrographs of unloaded and FTY720 loaded nanofibers (original magnification x2000) demonstrates similar morphologies of randomly aligned nanofibers. (C) Cumulative release of FTY720 from nanofibers using HPLC-MS. Approximately 2.4 μg of FTY720 was released by 21 days.

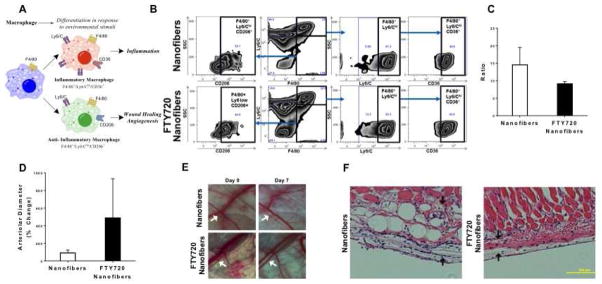

Soft tissue response to FTY720-loaded nanofibers

Macrophage cell phenotype is an important metric for understanding the inflammatory environment and assessing its potential to support regeneration. To predict the therapeutic potential of FTY720-loaded nanofibers, tissue surrounding subcutaneous implants in mice was examined for markers of M1 and M2 macrophages by flow cytometry. In this experiment, each animal received one unloaded and one FTY720-loaded sheet of nanofibers. The cells were compared based on their expression of F4/80 (macrophage), Ly6C (inflammatory cell), CD36 (M1-like macrophage), and CD206 (M2-like macrophage).

Proportions of F4/80lo and F4/80hi expression was nearly equivalent around the two implant types. Within the F4/80lo population, there was a greater expression of Ly6C on cells surrounding the nanofibers implant, possibly indicating important differences in cell types other than macrophages. This same trend occurred in the F4/80hi population, although to a lesser extent. In order to observe changes in the phenotype of macrophage populations, the F4/80hi population was further analyzed (Fig 2A–C).

Fig 2.

FTY720 modulates inflammatory response after scaffold implantation by (A) changing macrophage phenotype surrounding the implant. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of digested mouse dorsal skinfold tissue treated with unloaded or FTY720 loaded nanofibers. Gating strategy for F4/80 and Ly6/C. (C) FTY720 nanofibers decrease the ratio of inflammatory Ly6Chi/CD36+ to Ly6Clo/CD206+ tissue macrophages (F4/80+). (D) FTY720 nanofibers increase the arteriolar diameter of blood vessels surrounding the implant. (E) Intravital images of dorsal skinfold window chamber microvasculature showing the arteriolar diameter increase. H&E staining of (F) unloaded nanofibers or FTY720 loaded nanofibers in dorsal skinfold tissue (arrows show fibrous tissue surrounding implant).

The expression of CD36 (thrombospondin receptor) and CD206 (mannose receptor) was examined within this F4/80hi population. No difference was found in the Ly6ChiCD36+ cell population, however the Ly6CloCD206+ population of cells was larger surrounding the FTY720-loaded nanofiber implants. The decreased ratio of Ly6ChiCD36+ cells to Ly6CloCD206+ cells surrounding the FTY720-loaded implants indicates a decrease in the proportion of macrophages displaying an inflammatory phenotype (Fig 2).

Microvascular remodeling is predictive of a tissue’s ability to regenerate after injury [15]. Thus, we used the dorsal skinfold window chamber to examine the changes in murine microvasculature induced by FTY720-loaded or unloaded nanofiber implants. Arteriolar diameter increased on average for the FTY720-loaded nanofibers compared to their unloaded counterparts (Fig 2D–E). Histologically, after 7 days, the unloaded nanofibers result in a significantly larger fibrous capsular layer between the implant and the underlying reticular dermal tissue than those containing FTY720 (Fig 2F). Thus, the local release of FTY720 from PCL/PLAGA nanofibers reduces the intensity of the inflammatory response and increases the arteriolar blood supply in the murine soft tissues of a wound-healing model. These phenomena are critical for clinical acceptance of any implant therapy in development.

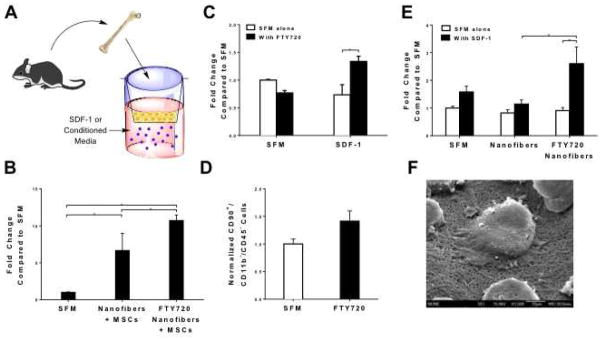

Effect on recruitment of regenerative cell types

Angiocrine signals released from endothelial cells promote the recruitment of progenitor and inflammatory cell types and further instruct their functional roles. Infiltration of osteoprogenitor cells derived from local tissue niches and circulating progenitor cell populations is a critical step during bone defect healing. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are one such source of osteoprogenitors that can differentiate into bone and secrete factors that direct inflammatory and reparative processes. Scaffolds that promote the migration and infiltration of bone marrow-derived progenitors have been shown to reduce inflammation and enhance angiogenesis around an implant [18]. Here, we assessed the ability of FTY720-loaded nanofibers to direct the secretory profile of MSCs isolated from vascular stromal fraction of epididymal fat pads of Sprague Dawley rats and enhance recruitment of bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells (BMNCs, which contains inflammatory cells, lymphocytes, and osteoprogenitors). MSCs were cultured on unloaded or FTY720-loaded nanofibers for 24 hours in order to generate conditioned media (CM) containing soluble secreted factors. CM from MSCs cultured on FTY720-loaded nanofibers (Fig 3F) recruits more BMNCs than CM generated by MSCs cultured on unloaded nanofibers (Fig 3A–B). Given that others have demonstrated interaction between S1P signaling and the SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling axis [19], we hypothesized that SDF-1α is the one of the primary MSC-derived factors by which BMNC migration is enhanced. To this end, we showed that FTY720 pre-treatment increases the migration of BMNCs and, more specifically, bone marrow-derived progenitors towards SDF-1α (Fig 3C–D). We also generated CM from unloaded and FTY720-loaded nanofibers in the presence of SDF-1α, allowing us to compare the effects of SDF-1α-mediated migration with migration induced by the entire MSC secretome. SDF-1α is a potent chemokine for myeloid-lineage cells that enhanced migration of BMNCs towards both serum free media (SFM) and CM obtained from unloaded nanofibers (Fig 3E). Additionally, SDF-1α enhanced recruitment of BMNCs to CM from FTY720-loaded nanofibers compared to unloaded nanofibers to a similar degree (approximately two-fold) to that of CM from MSCs cultured on FTY720-loaded or unloaded nanofibers. These results indicate that SDF-1α secreted by perivascular MSCs is indeed a key player in the recruitment of BMNCs and signaling through S1P receptors may increase cellular infiltration. Taken together, this suggests that FTY720-loaded nanofibers may support the recruitment, infiltration, and maintenance of cell populations critical for tissue remodeling.

Fig 3.

FTY720 loaded nanofibers interact with MSCs to direct their secretory profile. (A, B) CM generated from fat vascular stromal fraction derived MSCs cultured on unloaded or FTY720 loaded nanofibers induces migration of bone marrow cells towards SDF-1. (C) FTY720 pre-treatment increases the migration of bone marrow stromal cells and (D) bone marrow-derived progenitor cells towards SDF-1. (E) Conditioned media (CM) generated from FTY720 loaded nanofibers enhances migration of bone marrow cells towards SDF-1. (*p<0.01). Scanning electron micrographs demonstrate that MSCs adhere to and interact with (F) FTY720 nanofibers (original magnification x1500).

Bone regeneration in critical size mandibular defect

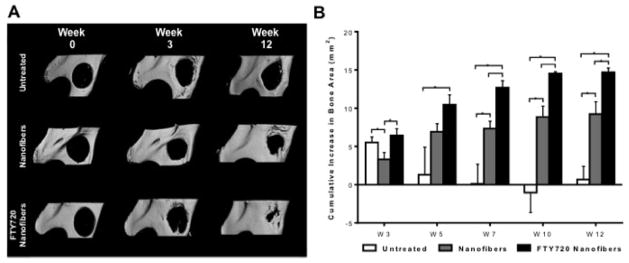

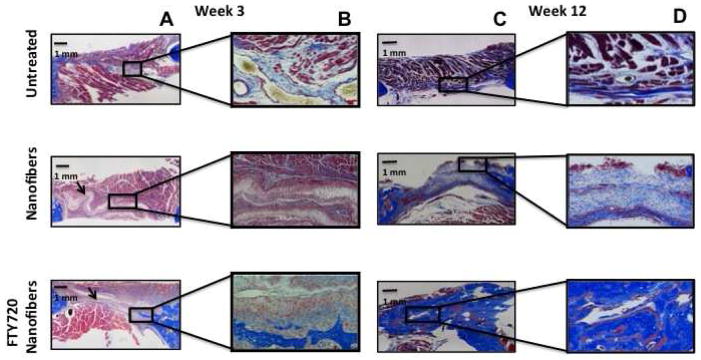

We have previously reported that PLAGA films loaded with FTY720 enhanced bone remodeling in a rat cranial defect model15. Recently, we also showed that allografts coated with PLAGA and FTY720 enhance cranial allograft incorporation and promote boney ingrowth into rat cranial defects by enhancing neovascularization [17]. Here, we assess the functional outcome of conditioning injured tissue for regeneration by showing that FTY720-loaded nanofibers enhance critical size mandibular defect repair. MicroCT three-dimensional representative images at weeks 0, 3, and 12 demonstrate the effect of FTY720 in defect healing (Fig 4A). FTY720 appears to have little effect on mineralization at week 3; however, by week 12, groups receiving FTY720-loaded nanofibers demonstrate enhanced boney ingrowth into the defect area. Two-dimensional quantification of these images at weeks 0, 3, 5, 7, 10, and 12 support this observation by demonstrating that FTY720-loaded nanofibers significantly increase new bone formation compared to no treatment or unloaded nanofibers treatment (Fig 4B). This observation is also reflected in the Masson’s trichrome histology of the defect region done at weeks 3 and 12 (Fig 5).

Fig 4.

Assessment of new bone formation in rat critical size mandibular defects. (A) Three-dimensional representative microCT images of the mandibular ramus on the day of surgery and 3 or 12 weeks post-surgery. Defects were left untreated or treated with unloaded nanofibers or FTY720 loaded nanofibers. (B) Two-dimensional quantification of new bone formation in the defect region was calculated using ImageJ image analysis software. FTY720 promotes more osseous ingrowth than unloaded nanofibers or no treatment. Bars indicate significance between groups (p<0.1 or *p<0.01).

Fig 5.

Assessment of new bone formation in rat critical size mandibular defects by Masson’s trichrome staining. Defects were left untreated or treated with unloaded nanofibers or FTY720-loaded nanofibers. (A) Representative images of mandibular defect 3 weeks post-surgery (original magnification x10). (B) High magnification image of a region with new bone formation 3 weeks post surgery (original magnification x40). (C) Representative images of mandibular defect 12 weeks post-surgery (original magnification x10). (D) High magnification image of a region with new bone formation 12 weeks post surgery (original magnification x40).

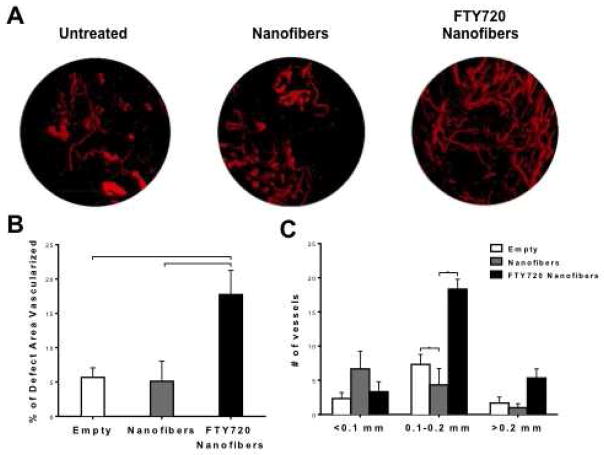

Neovascularization at site of injury

Neovascularization is a critical step in bone healing, as it is well documented that angiogenesis precedes osteogenesis [20]. Vessel formation in the defect area was visualized by perfusing sacrificed animals with MICROFILR radiopaque contrast agent, harvesting the defect area, and scanning with microCT. Representative 3D microCT images at week 12 demonstrate defect area neovascularization in response to no treatment, unloaded nanofibers, or FTY720-loaded nanofibers (Fig 6A). Vessel formation appears to be significantly enhanced in animals receiving FTY720-loaded nanofibers compared to both untreated and unloaded nanofibers controls. 2D quantification of the blood vessel area in the defect region demonstrates that FTY720-loaded nanofiber treatments lead to significantly greater blood vessel formation at week 12 (Fig 6B). Quantification of the diameter of newly formed blood vessels indicates that FTY720-loaded nanofibers primarily support the formation of mid-range (0.1–0.2 mm diameter) blood vessels (Fig 6C), which largely consists of arterioles and venules. Neither capillary (<0.1 mm diameter) nor larger blood vessel (>0.2 mm diameter) numbers were significantly affected by FTY720 delivery.

Fig 6.

Neovascularization in the defect area visualized with MICROFIL® enhanced microCT. (A) Representative images at week 12 demonstrate vessel perfusion with MICROFIL within the defect area. (B) Two-dimensional quantification of blood vessel area in the defect region was calculated using ImageJ image analysis software. (C) Number of vessels by vessel diameter within the defect area for the three treatment groups. (p<0.05 or **p<0.001).

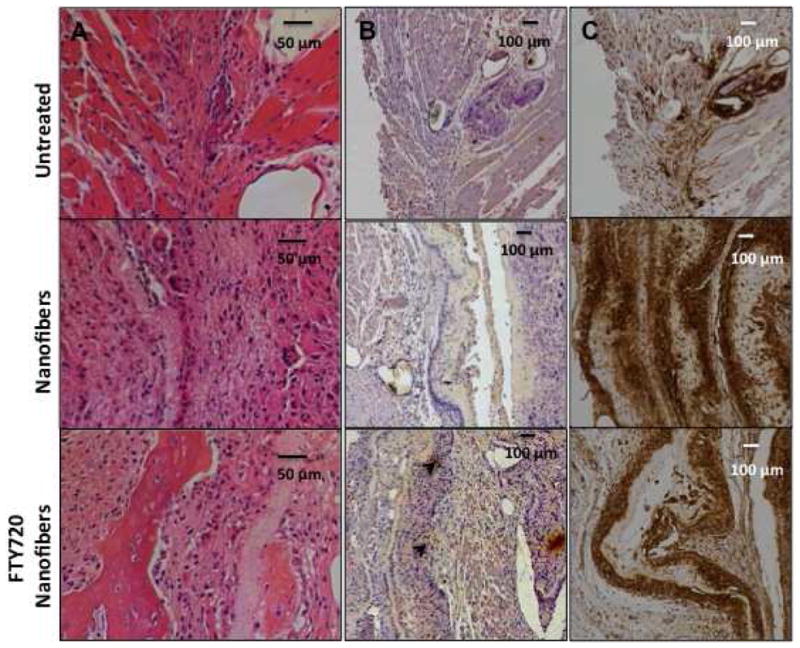

Local inflammatory response at site of injury

We investigated the temporal evolution of macrophage phenotype in a mandibular defect model to determine whether FTY720 promotes an anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotype similar to that observed in the mouse dorsal skinfold model and whether this plays a role in bone defect healing. We used immunohistochemistry to assess the phenotype of macrophages that were in close proximity to the defect site 3 weeks after treatment. The appearance of CCR7+ M1 macrophages surrounding the defect site decreased when animals were treated with FTY720-loaded nanofibers compared to treatment with unloaded nanofibers. However, the frequency of CD163+ M2 macrophages appeared to increase in the group treated with FTY720-loaded nanofibers (Fig 7). This suggests that the presence of FTY720 is either enhancing the recruitment, transdifferentiation or the local proliferation of M2 macrophages.

Fig 7.

FTY720 treatment decreases the recruitment of M1 macrophages to the defect site. Mandibular defect tissue stained 3 weeks after treatment for (A) H&E (B) CD163 (M2 marker, black arrowheads) and (C) CCR7 (M1 marker) to qualitatively evaluate inflammatory response following treatment with unloaded or FTY720-loaded nanofibers.

DISCUSSION

Many design criteria must be considered when developing a drug delivery vehicle for bone regeneration applications. Nanofiber scaffolds provide unique advantages over their bulk material counterparts, as the nanoscale topography and high surface-to-volume ratio improve interactions with cellular components. The fibrillar structure of nanofibers resembles the native extracellular matrix and provides a platform for cell adhesion and spreading, proliferation and differentiation [21]. Drug delivery via a nanofiber scaffold is also enhanced because the dissolution rate of the drug increases due to the larger surface area of the delivery vehicle [21]. Hence, release of osteogenic factors via nanofiber scaffolds at an optimal drug-loading ratio may accelerate bone regeneration. Here, we have shown that delivering the S1P receptor-targeting drug FTY720 in such scaffolds made of FDA approved polymers results in enhanced bone healing in mandibular defects as shown by microCT imaging (Fig 4) and histology (Fig 5).

Endogenous tissue engineering strategies harness the body’s innate mechanisms of repair by providing cues that guide cellular recruitment, proliferation, and differentiation in situ. A primary criteria of angiocrine signaling is the ability to instruct the recruitment, differentiation, and proliferation of progenitor and inflammatory cell types via soluble cues to areas of damaged endothelium during tissue remodeling. Macrophages are one of the early cellular responders to inflammation and injury, infiltrating the wound area and undergoing polarization within 24 hours of insult [22] in response to these signals. The role of macrophages in bone healing is not completely understood, although several groups have provided evidence suggesting that their role may be critical. Macrophages provide osteoinductive signals to osteoprogenitors including BMP-2 and TGF-β, the secretion of which are decreased in response to an inflammatory stimulus [23]. Depletion of macrophages in either a MAFIA mouse model or clodronate liposome-treated mice significantly impairs tibial fracture repair [24]. Moreover, macrophage phenotype has been correlated directly to regenerative outcome [25,26], indicating expansion of local macrophage populations may also play a role in bone healing. Specifically, CD206 (mannose receptor)-expressing macrophages are associated with two subclasses of pro-healing and regulatory macrophages, M2a and M2c [27,28]. S1P activates the macrophage S1P1 receptor and enhances the production of such alternatively activated anti-inflammatory macrophages [9]. Here, we have shown that local delivery of FTY720 from polymer nanofiber scaffolds affects the phenotype of macrophages present at an injury site by affecting their recruitment, differentiation, and/or their proliferation [29], as indicated by a higher ratio of anti-inflammatory (Ly6CloCD206+ cells) to pro-inflammatory macrophages (Ly6ChiCD36+ cells) in the tissue near FTY720-loaded scaffolds (Fig 2B). Implanting unloaded and FTY720-loaded nanofibers within the same animals demonstrated that the anti-inflammatory affect was localized to the tissue immediately surrounding the nanofiber implants and that the effect was not systemic. This observation circumvents potential systemic complications of using a drug intended for local activity. While it is known that monocytes migrate from the blood into tissues, the processes governing the transition to a particular macrophage phenotype are not completely known [30,31]. The results presented here suggest that S1P receptor signaling may play a role in the first phenotype a monocyte assumes upon entry, an early plastic change to another macrophage phenotype within a wound bed, or the proliferative capacity of specific macrophage subsets. Further experiments may elucidate the precise effect of FTY720 on M2 macrophage recruitment and proliferation following injury.

Vascularization of an injury site is a key metric in assessing a tissue’s potential for regeneration, as restoration of blood flow to damaged tissue provides a source of growth factors, nutrients, and circulating cell populations to the recovering injury site. In several instances, inadequate vascularization of implants has led to their failure in clinical translation attempts. S1P signaling has been shown to impact this process both through recruitment of angiogenic cell types [32] and the stabilization of newly-formed blood vessels [33]. The interaction between angiogenesis and local inflammatory response, and its repercussion on bone healing is complex due to paracrine signaling and direct cell contact between a diversity of cell types. Recent studies have shown that the temporal evolution of different pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory macrophages recruited to the wound site impacts local vascularization and wound healing [34]. Additionally, tissue-derived macrophages have been shown to interact with tip cells and induce angiogenesis and vessel anastomosis in a VEGF-independent manner [35]. We have shown that local FTY720 treatment increases both the amount of vascularization and the proportion of M2 macrophages at the defect site, suggesting that FTY720 therapy could condition injured tissue for regeneration through multiple, non-redundant mechanisms (Fig 6, 7). Moreover, it also induces vessel maturation as is reflected by an increase in the number of mid-ranged vessels in the animals treated with FTY720 in the bone defect model (Fig 6C) and an increase in the vessel diameter in the backpack model (Fig 2D–E). These results provide further evidence that immune cell types are critical to neovascularization and tissue remodeling and that S1P signaling may play a critical role in these processes. These observed effects could be attributed to the effect of FTY720 on local angiocrine signals and their ability to direct macrophage phenotype and consequent microvascular remodeling.

CONCLUSION

The ability of FTY720-loaded PCL/PLAGA polymer nanofibers to enhance cellular response to local signals and promote tissue regeneration was investigated in these studies. First, the properties of this drug delivery vehicle were assessed, including the effect of FTY720 loading on nanofiber morphology and surface energy. Angiocrine activity via recruitment of regenerative cell types was assessed in a dorsal skinfold mouse model and with in vitro migration assays. The ability to direct macrophage phenotype, promote microvascular remodeling, and recruit bone marrow mononuclear cells indicates that FTY720-loaded nanofibers have promising potential for enhancing tissue remodeling. Finally, the therapeutic advantages of using FTY720-loaded nanofibers to improve mandibular bone regeneration, defect site vascularization and local inflammatory response were demonstrated in a rat model. Our results suggest that local delivery of S1P receptor targeting drugs can be explored for treating critical size craniofacial defects.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH R01 DE019935 and NIH R01 AR056445. We would also like to acknowledge the University of Virginia Research Histology Core, Biotissue Repository Core, Flow Cytometry Core and the Animal Care and Use Committee. AD (rat defect model, mouse implant model, in vitro assays, microCT, microfil, histology), CES (in vitro assays, microCT), BBH (rat defect model, microfil) and DTB (mouse back model, mouse implant model) contributed to experimental design and data acquisition. AD, CES and DTB contributed to data analysis. AD, CES, BBH, DTB and EAB played a role in manuscript writing and final approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Maurer P, Eckert AW, Kriwalsky MS, Schubert J. Scope and limitations of methods of mandibular reconstruction: a long-term follow-up. Brit J Oral Maxill. 2010;48(2):100–4. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mariani PB, Kowalski LP, Magrin J. Reconstruction of large defects postmandibulectomy for oral cancer using plate and myocutaneous flaps: a long-term follow-up. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;35(5):427–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schliephake H, Weich HA, Dullin C, Gruber R, Frahse S. Mandibular bone repair by implantation of rhBMP-2 in a slow release carrier of polylactic acid--an experimental study in rats. Biomaterials. 2008;29(1):103–10. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herford AS, Lu M, Buxton AN, Kim J, Henkin J, Boyne PJ, Caruso JM, Rungcharassaeng K, Hong J. Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein 2 combined with an osteoconductive bulking agent for mandibular continuity defects in nonhuman primates. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70(3):703–16. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.02.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zétola A, Ferreira FM, Larson R, Shibli JA. Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 (rhBMP-2) in the treatment of mandibular sequelae after tumor resection. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;15(3):169–74. doi: 10.1007/s10006-010-0236-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herford AS. rhBMP-2 as an option for reconstructing mandibular continuity defects. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67(12):2679–84. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.07.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woo EJ. Adverse events after recombinant human BMP2 in nonspinal orthopaedic procedures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(5):1707–11. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2684-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schaier M, Vorwalder S, Sommerer C, Dikow R, Hug F, Gross ML, Waldherr R, Zeier M. Role of FTY720 on M1 and M2 macrophages, lymphocytes, and chemokines in 5/6 nephrectomized rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;297(3):F769–80. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90530.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hughes JE, Srinivasan S, Lynch KR, Proia RL, Ferdek P, Hedrick CC. Sphingosine-1-phosphate induces an anti-inflammatory phenotypes in macrophages. Circ Res. 2008;102(8):950–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.170779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sato C, Iwasaki T, Kitano S, Tsunemi S, Sano H. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor activation enhances BMP-2-induced osteoblast differentiation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;423(1):200–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.05.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Y, Wada R, Yamashita T, Mi Y, Deng CX, Hobson JP, Rosenfeldt HM, Nava VE, Chae SS, Lee MJ, Liu CH, Hla T, Spiegel S, Proia RL. Edg-1, the G protein-coupled receptor for sphingosine-1-phosphate, is essential for vascular maturation. J Clin Invest. 2000;106(8):951–61. doi: 10.1172/JCI10905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Golan K, Vagima Y, Ludin A, Itkin T, Cohen-Gur S, Kalinkovich A, Kollet O, Kim C, Schajnovitz A, Ovadya Y, Lapid K, Shivtiel S, Morris AJ, Ratajczak MZ, Lapidot T. S1P promotes murine progenitor cell egress and mobilization via S1P1-mediated ROS signaling and SDF-1 release. Blood. 2012;119(11):2478–88. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-358614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Juarez JG, Harun N, Thien M, Welschinger R, Baraz R, Pena AD, Pitson SM, Rettig M, DiPersio JF, Bradstock KF, Bendall LJ. Sphingosine-1-phosphate facilitates trafficking of hematopoietic stem cells and their mobilization by CXCR4 antagonists in mice. Blood. 2012;119(3):707–16. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-348904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sefcik LS, Aronin CE, Awojoodu AO, Shin SJ, Mac Gabhann F, MacDonald TL, Wamhoff BR, Lynch KR, Peirce SM, Botchwey EA. Selective activation of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors 1 and 3 promotes local microvascular network growth. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17(5–6):617–29. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petrie Aronin CE, Sefcik LS, Tholpady SS, Tholpady A, Sadik KW, Macdonald TL, Peirce SM, Wamhoff BR, Lynch KR, Ogle RC, Botchwey EA. FTY720 promotes local microvascular network formation and regeneration of cranial bone defects. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16(6):1801–9. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wynn TA. Fibrotic disease and the T(H)1/T(H)2 paradigm. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4(8):583–94. doi: 10.1038/nri1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang C, Das A, Barker D, Tholpady S, Wang T, Cui Q, Ogle R, Botchwey E. Local delivery of FTY720 accelerates cranial allograft incorporation and bone formation. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;347(3):553–66. doi: 10.1007/s00441-011-1217-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thevenot PT, Nair AM, Shen J, Lotfi P, Ko CY, Tang L. The effect of incorporation of SDF-1alpha into PLGA scaffolds on stem cell recruitment and the inflammatory response. Biomaterials. 2010;31(14):3997–4008. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimura T, Boehmler AM, Seitz G, Kuçi S, Wiesner T, Brinkmann V, Kanz L, Möhle R. The sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor agonist FTY720 supports CXCR4-dependent migration and bone marrow homing of human CD34+ progenitor cells. Blood. 2004;103(12):4478–86. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guillotin B, Bareille R, Bourget C, Bordenave L, Amédée J. Interaction between human umbilical vein endothelial cells and human osteoprogenitors triggers pleiotropic effect that may support osteoblastic function. Bone. 2008;42(6):1080. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Venugopal J, Low S, Choon AT, Ramakrishna S. Interaction of cells and nanofiber scaffolds in tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2008;84(1):34–48. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahdavian Delavary B, van der Veer WM, van Egmond M, Niessen FB, Beelen RH. Macrophages in skin injury and repair. Immunobiology. 2011;216(7):753–62. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Champagne CM, Takebe J, Offenbacher S, Cooper LF. Macrophage cell lines produce osteoinductive signals that include bone morphogenetic protein-2. Bone. 2002;30(1):26–31. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00638-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alexander KA, Chang MK, Maylin ER, Kohler T, Müller R, Wu AC, Van Rooijen N, Sweet MJ, Hume DA, Raggatt LJ, Pettit AR. Osteal macrophages promote in vivo intramembranous bone healing in a mouse tibial injury model. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(7):1517–32. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mokarram N, Merchant A, Mukhatyar V, Patel G, Bellamkonda RV. Effect of modulating macrophage phenotype on peripheral nerve repair. Biomaterials. 2012;33(34):8793–801. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.08.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geissmann F, Gordon S, Hume DA, Mowat AM, Randolph GJ. Unravelling mononuclear phagocyte heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10(6):453–60. doi: 10.1038/nri2784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.David S, Kroner A. Repertoire of microglial and macrophage responses after spinal cord injury. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12(7):388–99. doi: 10.1038/nrn3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zizzo G, Hilliard BA, Monestier M, Cohen PL. Efficient clearance of early apoptotic cells by human macrophages requires M2c polarization and MerTK induction. J Immunol. 2012;189(7):3508–20. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jenkins SJ, Ruckerl D, Cook PC, Jones LH, Finkelman FD, van Rooijen N, MacDonald AS, Allen JE. Local macrophage proliferation, rather than recruitment from the blood, is a signature of TH2 inflammation. Science. 2011;332(6035):1284–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1204351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smythies LE, Sellers M, Clements RH, Mosteller-Barnum M, Meng G, Benjamin WH, Orenstein JM, Smith PD. Human intestinal macrophages display profound inflammatory anergy despite avid phagocytic and bacteriocidal activity. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(1):66–75. doi: 10.1172/JCI19229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown BN, Ratner BD, Goodman SB, Amar S, Badylak SF. Macrophage polarization: an opportunity for improved outcomes in biomaterials and regenerative medicine. Biomaterials. 2012;33(15):3792–802. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walter DH, Rochwalsky U, Reinhold J, Seeger F, Aicher A, Urbich C, Spyridopoulos I, Chun J, Brinkmann V, Keul P, Levkau B, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S, Haendeler J. Sphingosine-1-phosphate stimulates the functional capacity of progenitor cells by activation of the CXCR4-dependent signaling pathway via the S1P3 receptor. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27(2):275–82. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000254669.12675.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takuwa Y, Du W, Qi X, Okamoto Y, Takuwa N, Yoshioka K. Roles of sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling in angiogenesis. World J Biol Chem. 2010;1(10):298–306. doi: 10.4331/wjbc.v1.i10.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Willenborg S, Lucas T, van Loo G, Knipper JA, Krieg T, Haase I, Brachvogel B, Hammerschmidt M, Nagy A, Ferrara N, Pasparakis M, Eming SA. CCR2 recruits an inflammatory macrophage subpopulation critical for angiogenesis in tissue repair. Blood. 2012;120(3):613–25. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-403386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fantin A, Vieira JM, Gestri G, Denti L, Schwarz Q, Prykhozhij S, Peri F, Wilson SW, Ruhrberg C. Tissue macrophages act as cellular chaperones for vascular anastomosis downstream of VEGF-mediated endothelial tip cell induction. Blood. 2010;116(5):829–40. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-257832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]