Abstract

Objective

This study investigated predictors and moderators of mood symptoms in the randomized controlled trial (RCT) of Multi-Family Psychoeducational Psychotherapy (MF-PEP) for childhood mood disorders.

Method

Based on predictors and moderators in RCTs of psychosocial interventions for adolescent mood disorders, we hypothesized that children’s greater functional impairment would predict worse outcome, while children’s stress/trauma history and parental expressed emotion and psychopathology would moderate outcome. Exploratory analyses examined other demographic, functioning, and diagnostic variables. Logistic regression and linear mixed effects modeling were used in this secondary analysis of the MF-PEP RCT of 165 children, ages 8–12, with mood disorders, a majority of whom were male (73%) and White, non-Hispanic (90%).

Results

Treatment nonresponse was significantly associated with higher baseline levels of global functioning (i.e., less impairment; Cohen’s d = 0.51) and lower levels of stress/trauma history (d = 0.56) in children and Cluster B personality disorder symptoms in parents (d = 0.49). Regarding moderators, children with moderately impaired functioning who received MF-PEP had significantly decreased mood symptoms (t = 2.10, d = 0.33) compared with waitlist control. MF-PEP had the strongest effect on severely impaired children (t = 3.03, d = 0.47).

Conclusions

Comprehensive assessment of demographic, youth, parent, and familial variables should precede intervention. Treatment of mood disorders in high functioning youth without stress/trauma histories and with parents with elevated Cluster B symptoms may require extra therapeutic effort, while severely impaired children may benefit most from MF-PEP.

Keywords: family psychoeducation, predictor, moderator, children, mood disorders

Although randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are the “gold standard” for evaluating treatment efficacy, much more can be learned from an RCT than is often reported in the literature (Kraemer, Wilson, Fairburn, & Agras, 2002, p. 877). Specifically, RCTs can help improve the efficacy and transportability of treatments by establishing an empirical basis for treatment manuals, matching clients to interventions, and maximizing operative mechanisms of change (Kraemer et al., 2002). However, few studies have examined the mechanisms (mediators) and conditions (moderators) associated with treatment-induced change (Nock, 2003; Paul, 1967).

Predictor and moderator analyses can provide valuable information regarding selection of optimal treatment for individuals, based on pretreatment clinical presentation and characteristics. Predictor analyses seek to identify variables that predict a positive versus negative response and that reflect a main effect on outcome, regardless of treatment group. Moderator analyses, on the other hand, investigate whether the effects of one intervention, versus another, are conditional on certain characteristics, with moderation operationalized as a statistical interaction between baseline characteristics and the intervention effect (Hinshaw, 2002; Kraemer et al., 2002). Thus, predictors are indicators of general prognosis, while moderators are prescriptive and can identify groups who are differentially responsive to a specific treatment, potentially revealing for whom an intervention may be particularly well-suited and for whom extra therapeutic effort may be required (Hinshaw, 2002).

Predictors and Moderators in RCTs for Adolescent Mood Disorders

Although research has identified a number of psychosocial Evidence-Based Treatments (EBTs) for youth with mood disorders, few studies have investigated the predictors and conditions associated with successful intervention (David-Ferdon & Kaslow, 2008; Fristad & MacPherson, 2013). This gap in research led the National Institute of Mental Health Workgroup on Psychosocial Intervention Development for Mood Disorders to identify the study of moderators of psychotherapy as a research priority (Hollon et al., 2002).

Several RCTs of EBTs for adolescents with diagnosed depression identified baseline predictors of mood outcome, including demographic, youth functioning, and family functioning variables. Regarding demographics, four studies found older adolescent age predicted worse outcome (Brent et al., 1998; Clarke et al., 1992; Curry et al., 2006; Jayson, Wood, Kroll, Fraser, & Harrington, 1998), though one study found the opposite (Rohde, Seeley, Kaufman, Clarke, & Stice, 2006). Sex and race did not predict immediate outcome, though one study found females were more likely to relapse (Curry et al., 2011).

In terms of youth functioning, worse mood outcome was predicted by higher levels of depression symptom severity (Asarnow et al., 2009; Birmaher et al., 2000; Brent, Kolko, Birmaher, Baugher, & Bridge, 1999; Brent et al., 1998; Clarke et al., 1992; Curry et al., 2006; Emslie et al., 2010; Vitiello et al., 2011; Wilkinson, Dubicka, Kelvin, Roberts, & Goodyer, 2009), melancholic features (Curry et al., 2006), functional impairment (Asarnow et al., 2009; Curry et al., 2006; Emslie et al., 2010; Jayson et al., 1998; Rohde et al., 2006; Vitiello et al., 2011; Wilkinson et al., 2009), hopelessness (Asarnow et al., 2009; Brent et al., 1998; Curry et al., 2006; Emslie et al., 2010; Rohde et al., 2006; Wilkinson et al., 2009), suicidal ideation (Asarnow et al., 2009; Curry et al., 2006; Rohde et al., 2006; Wilkinson et al., 2009), non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI; Asarnow et al., 2009; Vitiello et al., 2011), cognitive distortion (Brent et al., 1998), and negative or irrational thoughts (Clarke et al., 1992; Rohde et al., 2006), as well as lower levels of enjoyment and pleasant activities (Clarke et al., 1992), coping skills (Rohde et al., 2006), expectations for improvement (Curry et al., 2006), and treatment with selective-serotonin reuptake-inhibitors (SSRIs; Asarnow et al., 2009).

In addition, most studies identified higher number of comorbid diagnoses (Asarnow et al., 2009; Curry et al., 2006; Wilkinson et al., 2009), comorbid dysthymia (Brent et al., 1999; Emslie et al., 2010), comorbid or high anxiety (Brent et al., 1998; Clarke et al., 1992; Curry et al., 2006; Emslie et al., 2010; Wilkinson et al., 2009), comorbid or high disruptive behaviors (Brent et al., 1999; Rohde, Clarke, Lewinsohn, Seeley, & Kaufman, 2001; Rohde et al., 2006), comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; Rohde et al., 2001; Rohde et al., 2006), and substance abuse/dependence (Rohde et al., 2001; Vitiello et al., 2011) as predictors of worse outcome. In contrast, Clarke et al. (1992) found greater number of psychiatric comorbidities predicted better outcome, and Rohde et al. (2001) found comorbid anxiety was associated with greater improvement in depression.

Concerning family functioning, worse outcome was predicted by family difficulties in affective involvement (Brent et al., 1999) and conflict (Asarnow et al., 2009; Brent et al., 1999; Birmaher et al., 2000; Emslie et al., 2010; Feeny et al., 2009), low cohesion (Rohde et al., 2006), and parent noninvolvement (Clarke et al., 1992).

Several moderators of mood outcome were also identified in RCTs of EBTs for depressed adolescents. Similar to aforementioned treatment predictors, many moderators can be conceptualized as demographic, youth functioning, and family functioning variables. However, novel moderators, such as stress/trauma and parental psychopathology, have also emerged in the adolescent depression literature. An examination of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), Systematic Behavioral Family Therapy, and Nondirective Supportive Therapy (NST) found that adolescents with comorbid anxiety responded better to CBT than other treatments, while efficacy of CBT diminished in presence of maternal depression (Brent et al., 1998). Suicidal, depressed adolescents responded better to CBT versus NST, relative to non-suicidal youth (Barbe, Bridge, Birmaher, Kolko, & Brent, 2004a). Also, CBT was more efficacious than NST in the absence of sexual abuse, but was not superior to NST for those with a sexual abuse history (Barbe, Bridge, Birmaher, Kolko, & Brent, 2004b). In addition, evaluation of the Adolescents Coping with Depression Course (CWD-A) versus a Life Skills/Tutoring Control (LS) found CWD-A resulted in faster recovery time, relative to LS, among adolescents who were Caucasian, had recurrent depression, and had good coping skills (Rohde et al., 2006). Further, benefits of Interpersonal Psychotherapy versus treatment as usual (TAU) were strongest for adolescents with high levels of conflict with their mothers and social dysfunction with friends (Gunlicks-Stoessel, Mufson, Jekal, & Turner, 2010).

In the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS), which examined efficacy of fluoxetine, CBT, CBT + fluoxetine, and clinical management + pill placebo, combined treatment was more efficacious than fluoxetine for mild to moderate depression and for depression with high levels of cognitive distortion (Curry et al., 2006). Combined treatment and fluoxetine were equally effective for severe depression or depression with low levels of cognitive distortion. In addition, fluoxetine and combined treatment were equally effective for adolescents from low- or middle-income families, whereas the three active treatments were equivalent for adolescents from high-income families, though only combined treatment and CBT significantly surpassed control. Also, those with ADHD demonstrated similar improvements in all active treatments compared with control, whereas only CBT + fluoxetine was superior to control for those without ADHD (Kratochvil et al., 2009). In addition, adolescents from negative familial environments (i.e., disagreement on values/norms, poor communication, and dysfunctional levels of involvement and control) were more likely to benefit from fluoxetine alone, while youth with better family functioning benefited more from combined treatment (Feeny et al., 2009). Finally, trauma history also moderated treatment response (Lewis et al., 2010). Youth without trauma responded equally well to combined treatment and fluoxetine, both of which were more effective than CBT and control. Youth with trauma and physical abuse histories responded equally well to the four treatment conditions. However, teens with histories of sexual abuse who received combined treatment, fluoxetine, and control showed significant and equivalent improvement in depression, while youth who received CBT did not experience similar improvement.

In the Treatment of Resistant Depression in Adolescents (TORDIA) study, which focused on second-step treatment strategies (12 weeks of a medication switch and CBT or a medication switch alone) among adolescents with SSRI treatment-resistant depression, response to combined treatment was more likely among youth with no abuse history, lower levels of hopelessness, and more comorbid disorders (with a marginally significant effect for comorbid ADHD; Asarnow et al., 2009). Adolescents who were older, Caucasian, without NSSI, and with comorbid anxiety disorders and longer pharmacotherapy histories also experienced more benefit from combined treatment versus medication alone. When examining specific aspects of abuse history, Shamseddeen et al. (2011) found that those without physical or sexual abuse histories had a higher response to combination therapy than medication alone. Those who had been sexually abused demonstrated similar response to combination treatment and medication alone, while those who had been physically abused had a lower response to combination therapy.

Only one RCT of adolescents with bipolar disorders examined family functioning moderators of treatment. In an RCT of Family-Focused Treatment for Adolescents (FFT-A) versus brief psychoeducational treatment, Miklowitz et al. (2009) found parental expressed emotion (EE; criticism, hostility, and emotional overinvolvement) moderated the impact of FFT-A on mood symptoms. Adolescents in high-EE families showed greater reductions in depressive and manic symptoms in FFT-A than in brief psychoeducational treatment, suggesting that parental EE moderates the impact of family intervention on symptoms of youth bipolar disorder.

Thus, several predictors and moderators related to demographics, youth functioning, family functioning, stress/trauma, and parental psychopathology have been identified in RCTs with depressed adolescents. Only one study examined moderators of outcome among adolescents with bipolar disorders. To our knowledge, no RCTs have focused exclusively on school-aged children with diagnosed mood disorders and examined predictors and moderators of outcome, until now. Multi-Family Psychoeducational Psychotherapy (MF-PEP) is the sole psychosocial treatment that has been evaluated and demonstrated efficacy in two RCTs for school-aged children with diagnosed depression or bipolar disorder. This paper builds upon primary findings and secondary analyses in the MF-PEP RCT by examining predictors and moderators of outcome.

Multi-Family Psychoeducational Psychotherapy

MF-PEP is an adjunctive, group-based EBT for children with mood disorders between the ages of 8 and 12 and their parents (Fristad, Goldberg Arnold, & Leffler, 2011). The intervention follows a non-blaming, growth-oriented, biopsychosocial model using family systems and cognitive-behavioral techniques. Psychoeducation, social support, and skills development are theorized to lead to better understanding and management of mood disorders and result in improved attainment of and adherence to treatment, as well as decreased familial conflict and mood symptoms.

MF-PEP consists of eight 90-minute sessions that address mood and comorbid disorders, medication and psychosocial treatment, emotion regulation, problem-solving, effective communication, CBT skills, and symptom management. Each session briefly begins and ends with children and parents together, though families spend the majority of time in separate and simultaneous parent and child groups. Families are assigned weekly projects to practice and generalize skills and share with the group the following week. Treatment ends with a review and graduation ceremony.

Two RCTs demonstrated efficacy of MF-PEP versus waitlist control (WLC). During these studies, all families were also encouraged to continue TAU for ethical reasons and because MF-PEP is an adjunctive intervention. The initial RCT of 35 families found that by 6-month follow-up, parents who immediately received MF-PEP demonstrated improved: family interactions; knowledge of mood disorders; ability to obtain services; and attitudes towards treatment (Fristad, Goldberg-Arnold, & Gavazzi, 2002, 2003; Goldberg-Arnold, Fristad, & Gavazzi, 1999). Children reported increased social support from parents. Also, families provided positive consumer evaluations. The second RCT included 165 families and found that children who immediately received MF-PEP had a significantly greater decrease in mood symptom severity compared to WLC over 12-month follow-up, with improvement maintained at 18-month follow-up (Fristad, Verducci, Walters, & Young, 2009).

Mediator analyses in the larger RCT demonstrated that MF-PEP helped parents become better mental healthcare consumers by increasing knowledge about treatment, which then lead to attainment of higher quality services (Mendenhall, Fristad, & Early, 2009). When children received higher quality services that matched their needs, mood symptom severity decreased.

Finally, two secondary evaluations of comorbidities in the larger MF-PEP RCT found that the presence of comorbid anxiety and disruptive behaviors did not impact the effect of MF-PEP on mood symptoms (Boylan, MacPherson, & Fristad, in press; Cummings & Fristad, 2012). Though MF-PEP did not improve anxiety (Cummings & Fristad, 2012) or conduct disorder symptoms, it was associated with a small reduction in ADHD and oppositional defiant disorder symptoms (Boylan et al., in press). These findings are promising, given that adolescent depression RCTs suggest worse outcome among youth with comorbid conditions, though comborbid anxiety has sometimes been identified as a positive moderator of CBT. Nevertheless, results suggest that comorbidities may not influence mood severity outcome for children with mood disorders, and also indicate that predictors and moderators of treatment may differ between children and adolescents with mood disorders.

Goals of the Study

The goals of the current study were to identify prognostic and conditional indicators in the larger MF-PEP RCT. This marks the first examination of predictors and moderators in an RCT of a psychosocial EBT for school-aged children with diagnosed mood disorders. Based on adolescent RCT findings, we hypothesized that greater child functional impairment would predict worse outcome. Regarding moderators, we hypothesized that the efficacy of MF-PEP versus WLC would be reduced among youth with stress/trauma history and parents with low levels of expressed emotion and high levels of psychopathology. We also pursued exploratory analyses examining other demographic (i.e., age, sex, race, income), youth functioning (i.e., intelligence), and mood diagnosis variables, as these are important clinical considerations for which prior RCTs have not provided conclusive support for directional hypotheses.

Method

Sample and Procedures

This paper conducted secondary data analyses of the larger efficacy MF-PEP RCT (National Institute of Mental Health Grant R01MH061512), which included 165 children with mood disorders and their families (Fristad et al., 2009). All study procedures were approved by a Midwestern university’s Institutional Review Board. MF-PEP participants were recruited from both rural and urban settings in the Midwest through a previously developed referral network of local mental health professionals, presentations to local professional and community-based groups, and local media feature stories about the study. To be eligible, children had to be ages 8 to 11 at baseline, have a mood disorder, and have an IQ > 70. Only one child per family could participate. Informed consent and assent were obtained from parents and children, respectively.

After determining potential eligibility through a phone screen, the child and a parent, who was characterized as the primary informant, participated in the baseline assessment. Subsequently, families were randomized into either a group immediately receiving MF-PEP (IMM) or a one-year WLC. All children/families were encouraged to continue using TAU throughout the 18-month study; use of additional interventions was carefully monitored and has been reported elsewhere (Mendenhall et al., 2009). TAU included medication management, school-based services, psychotherapy, and other adjunctive interventions, such as respite care or therapeutic summer camps. TAU was continued for ethical reasons and also because the mechanism by which MF-PEP improves mood symptoms is due in part to improved service utilization. Stratified randomization was used after each set of 15 families completed baseline assessments to ensure equal distributions of mood disorders, comorbid disorders, and demographic variables. Project coordinators summarized these variables; the principal investigator completed randomization, but was masked to all other information. Follow-up assessments were completed by graduate research associates masked to treatment status. Families participated in follow-up assessments at 6, 12, and 18 months. IMM+TAU participated in MF-PEP between baseline and 6-month assessments, while WLC+TAU participated in MF-PEP between 12- and 18-month assessments. All assessments and 22 8-session MF-PEP groups were conducted at a Midwestern university medical center. Families received payment for assessments, as well as free parking and child care to enhance attendance.

Sample size of 165 families was determined a priori based on a power calculation (Cohen, 1988). This sample size would provide 70% power to detect a medium effect size in primary analyses, including adjustment for multiple comparisons. All children had a mood disorder: 70% (n = 115) had a bipolar spectrum disorder and 30% (n = 50) had a depressive spectrum disorder. All had comorbid diagnoses, including 97% with behavior disorders and 68% with anxiety disorders. At baseline, children’s age range was 8 to 11 (M = 9.9, SD = 1.3), with a majority being male (73%) and White, non-Hispanic (90%). The range of median family income was $40,000 to $59,000 with 11% of families reporting income of less than $20,000 and 20% reporting income of $100,000 or more. Previous analyses reported baseline demographic and clinical descriptive statistics for the sample by IMM+TAU and WLC+TAU, with no significant differences between the two groups (Fristad et al., 2009).

Measures

Primary outcome variable

Primary findings were previously reported (Fristad et al., 2009). The primary outcome variable, children’s mood symptom severity measured via the Mood Severity Index (MSI), was assessed at baseline and 6-, 12-, and 18-month follow-ups. Current analyses used the first three time points. The MSI combines items on the Children’s Depression Rating Scale – Revised (CDRS-R; Poznanski et al., 1984) and the Mania Rating Scale (MRS; Young, Biggs, Ziegler, & Meyer, 1978) to provide a single mood severity variable incorporating manic and depressive symptoms (described below). This was done to enhance the power of the study, by using one mood outcome measure as opposed to two, and as improvement in depression with simultaneous deterioration in mania, or vice versa, would not represent true improvement in overall mood symptom severity. Of note, the primary outcome for this study was “adequate clinical response” at 12-month follow-up, defined as improvement in MSI of ≥ 50%, to differentiate treatment responders versus nonresponders (Asarnow et al., 2009).

The CDRS-R (Poznanski et al., 1984) is conducted in interview format with parents and children to assess severity of 17 depressive symptoms in youth. Items use either a 1 to 5 or a 1 to 7 scale, with higher scores indicating increasing severity. Total scores range from 17 to 113. The CDRS-R has demonstrated adequate inter-rater reliability (r = .86), test-retest reliability (r = .81), and validity (Poznanski et al., 1984).

The MRS (Young et al., 1978) is an 11-item clinical rating scale conducted with parents and children to assess children’s manic symptoms. Items use either a 0 to 4 or a 0 to 8 scale, with higher scores indicating increasing severity. Total scores range from 0 (no symptoms) to 60 (severe symptoms). Validity and reliability of the MRS are adequate for adults and children (Fristad, Weller, & Weller, 1995; Youngstrom, Danielson, Findling, Gracious, & Calabrese, 2002). A study with children found significant internal consistency in MRS ratings (α = .91) and a one-factor solution from exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses with younger and older samples of youth (Youngstrom et al., 2002).

An MSI score was calculated with the formula (CDRS-R score- 17 × 11/17) + MRS score. The formula adjusts for the greater number of items on the CDRS-R and the difference in minimum scores for the two measures. As irritability is rated on both scales, this item was down-weighted by half on each measure to avoid double-counting this symptom. The MSI has a possible score range of 0 to 116 with four symptom severity categories: < 10 = minimal; 11–20 = mild; 21–35 = moderate; > 35 = severe.

Baseline measures used in analyses

This study used a subset of measures from the overall MF-PEP dataset (Fristad et al., 2009).

Child functioning

The Children's Global Assessment Scale (CGAS; Shaffer et al., 1983) is a clinical rating scale used to assess children's functional capacity. Scores range from 1 (severe impairment) to 100 (superior functioning). Reliability and validity are adequate.

The Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test (K-BIT; Kaufman & Kaufman, 1990) is a short intelligence test based on norms from a nationally standardized sample. It provides an estimate of overall, verbal, and nonverbal abilities. Reliability and validity have been well-established.

Family Functioning

The Expressed Emotion Adjective Checklist (EEAC; Friedman & Goldstein, 1993) is a self-report instrument completed by parents in the current study. It contains 20 positive and negative descriptors of criticism and emotional overinvolvement with rating on a 1 (never) to 8 (always) Likert scale. The positive and negative subscale score totals range from 10 to 80. Items are completed twice, first to record the parent’s behavior toward the child, and second to record the child’s behavior toward the parent. The instrument has been shown to measure expressed emotion comparable to other established measures.

Stress/Trauma

The Coddington Life Events Scale for Children (Coddington, 1983) assesses parental report of children’s stressors, ranging from traumatic events to other significant life changes (e.g., starting a new school, birth of a sibling). It lists 36 stressors, and a total score quantifies the amount of stress the child has experienced. Higher total scores indicate a greater number of significant life events. Test-retest reliability and parent-child agreement are adequate.

The Children’s Interview for Psychiatric Syndromes – Child Form (ChIPS; Weller, Weller, Rooney, & Fristad, 1999a) and Parent Form (P-ChIPS; Weller, Weller, Rooney, & Fristad, 1999b) are structured diagnostic interviews completed with children and parents, respectively, which assess psychopathology according to DSM-IV criteria in youth ages 6 to 18. ChIPS and P-ChIPS assess 20 behavioral, anxiety, mood, and other syndromes, as well as stressors. Adequate reliability and validity have been demonstrated with children and adolescents, and in inpatient and outpatient research settings (Weller, Weller, Fristad, Rooney, & Schecter, 2000). In this study, significant inter-rater reliability was obtained (k = .78 to .82).

Dichotomous items on the ChIPS were used to generate six indices of trauma/stress: Illness; Arguing; Criticism; Negligence; Physical Abuse; and Sexual Abuse. These indices were then collapsed to create a Stress/Trauma Index. Only child report was taken into account, as stress/trauma items asked mainly about parental perpetrators, and social desirability in parents’ responses may have biased results. Two items comprise Illness: “is someone in your family very sick;” “has he/she been in the hospital a lot.” Four items comprise Arguing: “is there a lot of arguing or fighting in your family;” “is arguing mostly among the children/teenagers;” “is there arguing between your mom and dad;” and “is there arguing between your parents and you and/or your brother(s)/sister(s).” Three items comprise Criticism: “does your mother/father criticize you a lot;” “does your mother/father ever say that he/she wishes you had not been born;” and “does your mother/father tell you that she/he doesn’t like you or that she/he hates you.” Four items comprise Negligence: “does your mother/father ignore you a lot;” “do you miss doctor’s appointments because your mother/father doesn’t bother to get you there;” “do you not have meals because your mother/father doesn’t bother to make them (not because of lack of money);” “do you not have other things you need, like clothes, because your mother/father hasn’t bothered to get them for you;” and “has your mother/father ever made you go for a whole day without eating as punishment.” Four items comprise Physical Abuse: “when you do something wrong, are you spanked or hit;” “do you sometimes get hit or spanked for no good reason (just because your mother/father is mad and you just happen to be around);” “are you afraid your mother/father will hurt you very badly when she/he punishes you;”and “has your mother/father ever physically punished you so hard that you hurt the next day, or you had bruises or marks on your body, or you had to see a doctor.” Finally, one item measures Sexual Abuse: “has anyone ever tried to undress you, touch you between the legs, make you get in bed with him or her, or make you play with his or her private parts.”

Excluding Illness, the remaining indices demonstrated significant positive correlations with each other (rs = .27 to .74). After Principal Component Analysis, a single factor emerged explaining 55% of the variance. This single factor demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .74).

Parental Psychopathology

The Psychiatric Diagnostic Interview – Revised (PDI-R; Othmer, Penick, Powell, Read, & Othmer, 1989) is a structured diagnostic interview used to assess 17 psychiatric diagnoses and symptoms. Reliability and validity are acceptable.

The Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD; Hamilton, 1967) is a 24-item clinical rating scale that was used to assess parents’ depressive symptom severity. Total scores range from 0 to 72. This instrument has demonstrated high inter-rater reliability and adequate levels of validity (Hedlund & Vieweg, 1979).

Parents were also administered the MRS (Young et al., 1978) to assess manic symptom severity. As described previously, 11 items yield total scores ranging from 0 to 60 with increasing severity, and reliability and validity are adequate for adults, the age group for which the instrument was originally designed.

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders – Patient Questionnaire (SCID-II-PQ; First, Gibbon, Spitzer, Williams, & Benjamin, 1997) is a self-report screener with 119 yes/no items that typically accompanies the SCID II structured interview. It assesses Axis II personality disorders according to DSM-IV criteria. The SCID-II-PQ has demonstrated adequate diagnostic agreement when compared with the SCID II structured interview (Ekselius, Lindstrom, von Knorring, Bodlund, & Kullgren, 1994).

Analyses

As aforementioned, and consistent with prior adolescent depression RCT predictor and moderator methodology (Asarnow et al., 2009), the primary outcome for this study was “adequate clinical response” at 12-month follow-up, defined as improvement in MSI of ≥ 50%. Youth meeting this criterion were categorized as responders, while youth not meeting this criterion were considered nonresponders. All analyses were intent-to-treat and used the Multiple Imputation procedure for missing longitudinal values, imputing 10 sets of values (Rubin, 1996).

As outlined by Kraemer et al. (2002), predictors were defined as baseline variables that had a main effect on outcome regardless of group (IMM+TAU or WLC+TAU). Predictor analyses proceeded in two steps. First, independent sample t tests and χ2 analyses were conducted to examine which of the candidate explanatory variables were associated with adequate versus inadequate treatment response. Then, variables significantly associated with outcome were entered into a logistic regression predicting treatment response, controlling for age, sex, and race.

Moderators, defined as baseline variables that had interactive effects with group assignment (IMM+TAU or WLC+TAU) on outcome, were then examined (Kraemer et al., 2002). Specifically, linear mixed effects modeling (LME) was used to analyze the moderating effect of variables measured at the baseline assessment, and that were identified as predictors in previous analyses, on the impact of MF-PEP on children’s mood symptom severity. LME accounts for outcome changes over time in a nested dataset and models repeated measures with subject-specific regression coefficients that are parameters allowed to vary over individuals (Singer & Willett, 2003). The current analyses used the full MF-PEP sample and compared children’s mood symptom severity in IMM+TAU and WLC+TAU using an LME model with fixed slopes and random intercepts by participant. Moderation was evaluated via treatment X baseline predictor X time interactions.

Thus, regarding predictor hypotheses, improvement slope for children’s mood symptom severity, regardless of treatment group, was expected to be steepest among children with higher global functioning. Regarding moderators, improvement slope for children’s mood symptoms was hypothesized to be steepest among children in IMM+TAU (versus WLC+TAU) with no stress/trauma history and parents’ with high levels of expressed emotion and low levels of psychopathology. Exploratory variables (i.e., age, sex, race, income, intelligence, mood diagnosis) were also examined.

Analyses were run using SPSS 19.0. Despite multiple comparisons, α was set at .05 (two-sided) due to the exploratory nature of analyses.

Results

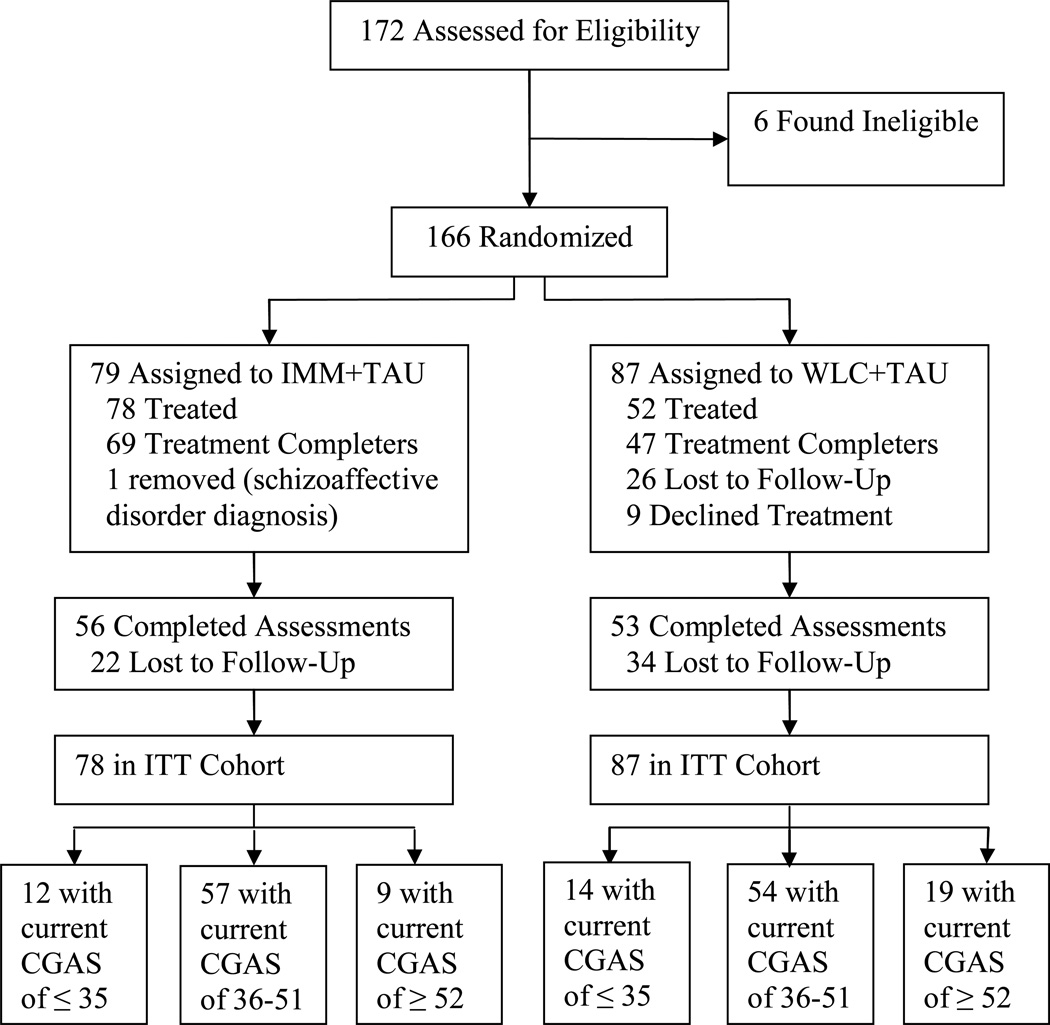

Recruitment and follow-up assessments were conducted from 2001 to 2005. The primary study ended following completion of all follow-up assessments. Figure 1 summarizes participant flow of the MF-PEP RCT. Current study hypotheses concerned the effect of predictive and moderating variables (i.e., demographic, youth functioning, family functioning, stress/trauma, paternal psychopathology) on children’s mood symptom severity at follow-up assessments in the MF-PEP RCT. Approximately 17% (n = 28) of the entire sample had at least one missing value in these potential predictors and moderators at baseline. When those with missing data were compared to those without missing data on the MSI, no significant differences were observed [t (163) = 0.15, p>.05].

Figure 1.

CONSORT randomized trial flow diagram. IMM = immediate treatment group; WLC = waitlist control group; TAU = treatment as usual; Treatment Completers = completed ≥ 6 sessions; ITT = intent-to-treat. CGAS= Children’s Global Assessment Scale score.

Predictors

Nonresponse (versus adequate clinical response) was significantly associated with higher baseline levels of global functioning in children (Cohen’s d = 0.51) and Cluster B personality disorder symptoms in parents (d = 0.49). Nonresponse was also significantly associated with lower baseline levels of stress/trauma in children (d = 0.56), especially negligence (d = 0.56), physical abuse (d = 0.45), and arguing (d = 0.34). Stated differently, treatment responders had significantly lower global functioning (i.e., greater impairment), higher levels of stress/trauma, and parents with lower levels of Cluster B personality disorder symptoms (see Table 1). Logistic regression adjusting for age, sex, and race indicated that the most parsimonious baseline predictors were children’s global functioning and stress/trauma (see Table 2). Specifically, logistic regression confirmed that the likelihood of adequate clinical response increased as baseline levels of children’s global functioning decreased and stress/trauma increased.

Table 1.

Predictors of Adequate versus Inadequate Response

| Nonresponders (n = 115), 70% |

Responders (n = 50), 30% |

χ2 or t-test | Cohen’s d |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics, n (%) | ||||

| Age, M (SD) | 9.8 (1.2) | 9.9 (1.3) | 0.47 | 0.08 |

| Sex (male) | 82 (71.3) | 39 (78.0) | χ2(1) = 0.80 | 0.14 |

| Race (white) | 105 (91.3) | 45 (90.0) | χ2(1) = 0.07 | 0.04 |

| Family Income (≥ $60,000) | 56 (48.6) | 23 (46.0) | χ2(1) = 0.10 | 0.05 |

| Child Mood Diagnosis, n (%) | ||||

| DSD (ChIPS & P-ChIPS) | 33 (28.7) | 17 (34.0) | χ2(1) = 0.46 | 0.10 |

| BPSD (ChIPS & P-ChIPS) | 82 (71.3) | 33 (66.0) | ||

| Child Functioning, M (SD) | ||||

| Global Functioning (CGAS) | 44.9 (7.5) | 41 (7.6) | 3.03*** | 0.51 |

| Overall Intelligence (KBIT) | 106.3 (14.3) | 107.8 (16.0) | −0.59 | 0.10 |

| Verbal Intelligence | 103.7 (12.6) | 103.5 (14.7) | 0.08 | 0.01 |

| Visual-Spatial Intelligence | 107.6 (16.5) | 110 (16.6) | −0.85 | 0.14 |

| Family Functioning, M (SD) | ||||

| Child Expressed Emotion (EEAC) | −4 (17.1) | .66 (21.0) | −1.37 | 0.25 |

| Parent Expressed Emotion (EEAC) | 33.1 (15.6) | 31.6 (17.0) | 0.54 | 0.09 |

| Stress/Trauma, M (SD) | ||||

| Stressful Life Events (Coddington) | 189.4 (117.3) | 158.9 (93.0) | 1.76 | 0.27 |

| Stress/Trauma Index (ChIPS) | 3.12 (2.99) | 5.11 (4.51) | −2.83** | 0.56 |

| Illness | 0.94 (0.86) | 0.89 (0.86) | 0.34 | 0.06 |

| Arguing | 1.6 (1.4) | 2.1 (1.6) | −2.00* | 0.34 |

| Criticism | 0.42 (0.67) | 0.71 (1.0) | −1.85 | 0.36 |

| Negligence | 0.30 (0.89) | 0.90 (1.4) | −2.76** | 0.56 |

| Physical Abuse | 0.63 (0.97) | 1.1 (1.2) | −2.42* | 0.45 |

| Sexual Abuse (yes), n (%) | 15 (13.0) | 12 (24.0) | χ2(1) = 3.06 | 0.27 |

| Parental Psychopathology, M (SD) | ||||

| Psychiatric Disorders (PDI-R) | 0.88 (1.21) | 0.64 (0.94) | 1.36 | 0.21 |

| Psychiatric Symptoms (PDI-R) | 0.85 (0.97) | 0.75 (0.83) | 0.63 | 0.11 |

| Depression Symptoms (HRSD) | 8.6 (8.0) | 6.7 (6.1) | 1.65 | 0.25 |

| Mania Symptoms (MRS) | 20.2 (11.1) | 21.4 (9.7) | −0.65 | 0.11 |

| Cluster A PD Symptoms (SCID-II-PQ) | 0.19 (0.16) | 0.15 (0.13) | 1.67 | 0.26 |

| Cluster B PD Symptoms (SCID-II-PQ) | 0.13 (0.14) | 0.08 (0.08) | 2.87** | 0.40 |

| Cluster C PD Symptoms (SCID-II-PQ) | 0.38 (0.24) | 0.32 (0.19) | 1.70 | 0.26 |

Note. DSD = Depressive Spectrum Disorder; BPSD = Bipolar Spectrum Disorder; ChIPS & P-ChIPS = Children’s Interview for Psychiatric Syndromes – Child Form and Parent Form; CGAS = Children’s Global Assessment Scale; K-BIT = Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test; EEAC = Expressed Emotion Adjective Checklist; Coddington = Coddington Life Events Scale for Children; PDI-R = Psychiatric Diagnostic Interview – Revised; HRSD = Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; MRS = Mania Rating Scale; SCID-II-PQ = Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders, Patient Questionnaire.

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.005, two-tailed

Table 2.

Logistic Regression Predicting Treatment Response from Significant Explanatory Variables

| 95% CI | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Β | SE | Wald χ2 | df | Odds Ratio | Lower | Upper | |

| Age | 0.04 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 1 | 1.04 | 0.77 | 1.42 |

| Sex | −0.38 | 0.47 | 0.99 | 1 | 0.67 | 0.26 | 1.73 |

| Race | −0.22 | 0.83 | 0.35 | 1 | 0.97 | 0.18 | 5.12 |

| Global Functioning | −0.04 | 0.02 | 3.28 | 1 | 0.96 | 0.91 | 1.01 |

| Stress/Trauma Index | 0.12 | 0.05 | 5.38* | 1 | 1.12 | 1.01 | 1.25 |

| Parents’ Cluster B PD Symptoms | −4.36 | 2.42 | 5.69 | 1 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 1.63 |

Note. PD = personality disorder.

p < 0.05, two-tailed

Moderators

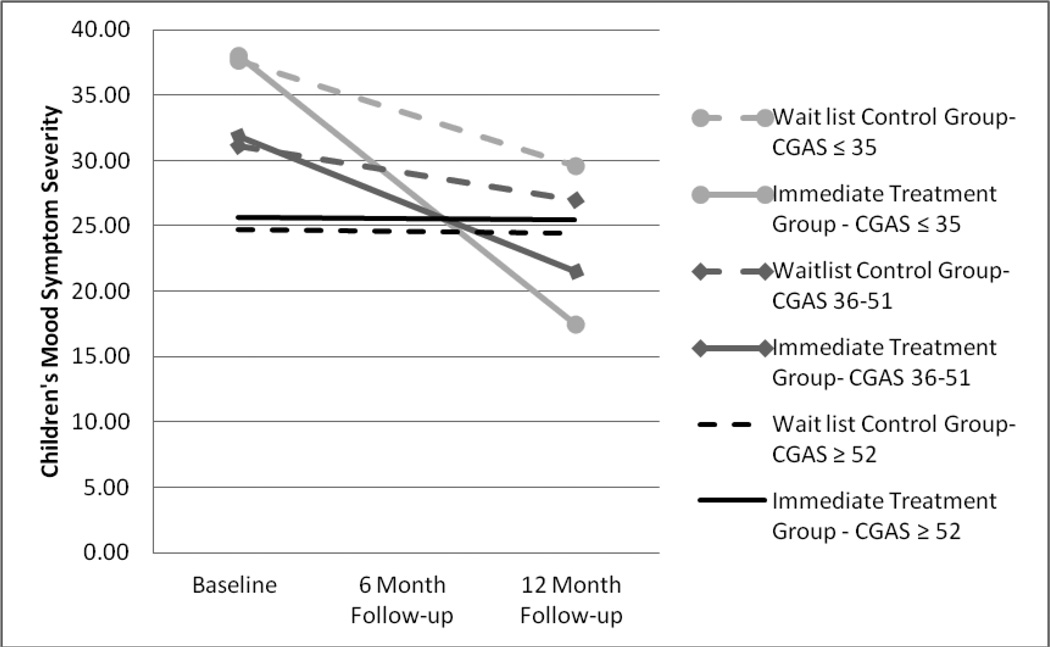

Based on hypothesized moderators, calculated confidence intervals from logistic regression, and the exploratory nature of these analyses, a series of linear mixed effects regression models using the intent-to-treat cohort of 165 participants tested the moderating effects of children’s global functioning and stress/trauma history, and parents’ expressed emotion and Cluster B personality disorder symptoms, on the treatment effect of MF-PEP. Linear mixed effects regression models found that global functioning was the only variable that significantly moderated effects of MF-PEP on children’s mood symptom severity (see Table 3). The model focusing on children’s global functioning revealed a three-way interaction between treatment group, CGAS, and time (F1, 293.5 = 4.061, p = .045) on MSI scores, indicating a differential treatment effect for children with low versus high global functioning. Specifically, for children with severely impaired CGAS scores (≤ 35), the estimated slope was −10.28 (95% confidence interval [CI] −13.47 to −7.09) for IMM+TAU and −4.02 (95% CI −7.10 to −0.95) for WLC+TAU. For children with relatively high CGAS scores (≥ 52), the estimated slope was −0.06 (95% CI −3.22 to 3.09) for IMM+TAU and −0.10 (95% CI −2.70 to 2.49) for WLC+TAU. Thus, higher global functioning among children was associated with less severe mood symptom severity in the MF-PEP group prior to treatment and a smaller overall treatment effect (see Figure 2). Based on this model, children with relatively high CGAS scores of ≥ 52, which is one standard deviation above the mean for the entire sample (M = 43.74, SD = 8.41), would have little or no treatment effect from participation in MF-PEP (t = 0.27, d = 0.04). However, children with moderately impaired CGAS scores of 36 to 51 (which includes the average CGAS score of 44 plus or minus one standard deviation) in IMM+TAU versus WLC+TAU had significantly decreased mood symptom severity as a result of MF-PEP (t = 2.10, d = 0.33). MF-PEP had an even stronger effect on mood symptoms for children with severely impaired CGAS scores of ≤ 35, which is one standard deviation below the mean (t = 3.03, d = 0.47).

Table 3.

Moderating Effect of Global Functioning on Children’s Mood Symptom Severity Response to Multi-Family Psychoeducational Psychotherapy

| 95 % CI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | t ratio | df | Lower | Upper | |

| Intercept | 31.85 1.66) | 19.31*** | 299.9 | 28.57 | 35.13 |

| Time | −5.17 (1.08) | −4.78*** | 285.9 | −7.30 | −3.04 |

| Treatment Group | −0.68 (2.29) | −0.29 | 300.8 | −5.19 | 3.03 |

| CGAS | −0.74 (0.20) | −3.55*** | 302 | −1.15 | −.33 |

| Treatment Group × Time | 3.10 (1.50) | 2.06* | 288.3 | .14 | 6.06 |

| Treatment Groups × CGAS | −0.02 (0.27 | −0.10 | 302.2 | −.57 | .51 |

| Time × CGAS | 0.60 (0.14) | 4.27*** | 293.8 | .32 | .88 |

| Treatment Group × Time × CGAS | −0.37 (0.18) | −2.01* | 293.5 | −.73 | −.01 |

Note. Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS) measures children’s current global functioning.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Figure 2.

Effect of Multi-Family Psychoeducational Psychotherapy on children’s mood symptom severity as moderated by children’s current global functioning. CGAS= Children’s Global Assessment Scale.

Linear mixed effects regression models found that the following variables did not moderate the effects of MF-PEP on children’s mood symptom severity: children’s stress/trauma history (F1, 296.1 = 1.432, p = .232); parental expressed emotion (F1, 271.3 = 1.097, p = .296); and parental Cluster B personality disorder symptoms (F1, 307.4 = 0.204, p = .652).

Discussion

The current study marks the first investigation of predictors and moderators in an RCT of a psychosocial EBT, MF-PEP, for childhood mood disorders. Findings indicated that treatment responders had significantly lower global functioning (i.e., greater impairment), higher levels of stress/trauma, and parents with lower levels of Cluster B personality disorder symptoms. Children’s global functioning also moderated the treatment effect of MF-PEP. Specifically, MF-PEP had a smaller impact on mood symptoms for children who at baseline were higher functioning, albeit clearly still within the clinical range (CGAS ≥ 52). MF-PEP had the strongest effect on mood symptoms for severely impaired children (CGAS ≤ 35). These findings are discussed within the context of adolescent mood disorder RCT predictor and moderator results and study limitations.

In keeping with findings in RCTs of EBTs for depressed adolescents, we hypothesized that greater functional impairment would predict treatment nonresponse (Asarnow et al., 2009; Curry et al., 2006; Emslie et al., 2010; Jayson et al., 1998; Rohde et al., 2006; Vitiello et al., 2011; Wilkinson et al., 2009). However, functional impairment predicted outcome in the opposite direction: youth with lower functioning benefitted more from treatment.

Subsequent analyses, which revealed that children’s global functioning was a moderator in the RCT, shed some light on surprising impairment findings. MF-PEP had a smaller treatment effect for children with higher global functioning at baseline. Since children with higher levels of global functioning tended to have less severe mood symptoms at baseline, these children had less room for improvement following the MF-PEP intervention and may have already been utilizing some of the presented skills, minimizing a potential treatment effect. Conversely, families of children with lower levels of global functioning at baseline experienced greater improvement in children’s symptom severity, suggesting MF-PEP was effective in providing the education and skills needed by families with children who were most impaired. More specifically, these results suggest that MF-PEP may be most impactful for children with at least moderate functional impairment (CGAS ≤ 51), as there was little to no treatment effect for children functioning at a CGAS level higher than this. Severely impaired children (CGAS ≤ 35) showed the most improvement in mood symptoms. Though not initially hypothesized, some adolescent depression RCTs found greater impairment, conceptualized as indicators of more severe depression (Barbe et al., 2004a; Rohde et al., 2006) or comorbidities (Asarnow et al., 2009; Brent et al., 1998), to be a positive moderator of CBT. Although functional impairment typically predicts worse prognostic outcome in adolescent studies, cumulating evidence suggests that these variables may actually moderate treatment, with more impaired youth exhibiting greater response to CBT-based interventions.

Other unexpected predictors of outcome included stress/trauma and parental psychopathology. In line with findings from adolescent depression RCTs (Asarnow et al., 2009; Brent et al., 1998; Barbe et al., 2004b; Lewis et al., 2010: Shamseddeen et al., 2011), we expected these variables to moderate the treatment effect of MF-PEP, in that youth with stress/trauma history and parents with high levels of psychopathology would respond more poorly to MF-PEP. However, these variables functioned solely as main effects. Youth with parents with high levels of Cluster B personality disorder symptoms experienced worse outcome. Though not initially hypothesized, this finding intuitively makes sense. Research has consistently documented considerable impairment among adults with Cluster B personality disorders, especially borderline personality disorder (Leichsenring, Leibing, Kruse, New, & Leweke, 2011). Severely impaired parents in WLC+TAU may have been unable to access appropriate services for their children or follow-through with treatment recommendations, while impaired parents in MF-PEP+TAU may have been unable to effectively utilize therapeutic skills and help their children generalize techniques, especially if they were not seeking their own mental health treatment. Interestingly, parents’ general psychiatric and mood symptoms were not related to outcome, despite research demonstrating associations between treatment of parents’ depression and improvement in children’s psychiatric symptoms (Gunlicks & Weissman, 2008). Thus, although prior research suggests that treatment of parents’ mood symptoms may offer added benefit for youth, our findings indicate that improvement in children’s mood is not necessarily compromised by presence of parental psychiatric and mood symptoms pre-treatment.

Stress/trauma also functioned as a main effect, but in an unexpected direction: youth with history of stress/trauma experienced more improved outcomes. This is contrary to most adolescent depression RCTs (Asarnow et al., 2009; Barbe et al., 2004b; Lewis et al., 2010; Shamseddeen et al., 2011) and mood disorder outcome literature in general (Nanni, Uher, & Danese, 2012), which found stress/trauma history to be a negative moderator or predictor of outcome, respectively. However, findings are somewhat consistent with adult literature, which demonstrated that chronically depressed adults with maltreatment histories preferentially responded to psychotherapy versus medication (Nemeroff et al., 2003). In the current study, stress/trauma history was largely conceptualized within the family context, with significant stress/trauma primarily consisting of arguing, negligence, and physical abuse. As all children received TAU, and as treatment of childhood mood disorders often involves family members (and this is certainly emphasized in MF-PEP), these treatments may have incorporated a familial component. Thus, parents who previously argued with, neglected, or abused their children may have developed more effective parenting strategies as a result of MF-PEP and/or TAU, subsequently enhancing mood outcome. Similarly, children’s stress/trauma history may have exacerbated mood symptoms at baseline, thus allowing more room for improvement following treatment. In addition, primary outcomes were at 12-month follow-up, not post-treatment. Thus, stress/trauma history may be a negative predictor or moderator of acute treatment outcome, but enhance outcomes over follow-up, during which children receive additional services.

Lastly, parental EE neither predicted nor moderated outcomes. This is contrary to hypotheses and findings from adolescent mood disorder RCTs, which found poor familial environment to predict worse outcome (Asarnow et al., 2009; Birmaher et al., 2000; Brent et al., 1999; Clarke et al., 1992; Emslie et al., 2010; Feeny et al., 2009; Rohde et al., 2006), or to moderate treatment response, with impaired families benefiting more from psychosocial intervention (Gunlicks-Stoessel et al., 2010; Miklowitz et al., 2009). Though surprising, this finding is promising, as it suggests that youth from families of varied environments responded equally well to treatment, with outcome unaffected by pretreatment familial factors. It may be that familial interaction styles among children with mood disorders, as opposed to adolescents, are less ingrained and more amenable to treatment, and that – regardless of dysfunction within the family – applied treatments can be helpful.

Finally, exploratory demographic (i.e., age, sex, race, income), youth functioning (i.e., intelligence), and mood diagnosis variables did not predict or moderate outcome. Past research demonstrated older adolescents typically fared worse in CBT RCTs (Brent et al., 1998; Clarke et al., 1992; Curry et al., 2006; Jayson et al., 1998). As the MF-PEP sample included only school-aged children, truncated age range may have limited the ability to detect differences; alternately, it may be that children’s age does not influence outcome. Similarly, sex and race have inconsistently affected outcome in the adolescent literature (Asarnow et al., 2009; Curry et al., 2006; Curry et al., 2011; Rohde et al., 2006). As the MF-PEP sample was predominantly male and Caucasian, limited diversity may have hindered the ability to detect differences. Income moderated outcome in only one adolescent depression study (Curry et al., 2006), and did not affect outcome in the current trial; thus, income may not be a robust moderator. Cognitive abilities also did not impact change in mood symptom severity, though this is not terribly surprising, as inclusion criteria in the current study limited variability (IQ > 70), and another study found verbal intelligence did not impact treatment response (Curry et al., 2006). Interestingly, mood diagnosis did not affect outcome, which is promising, as it suggests that treatment response was equivalent regardless of diagnosis. However, as the sample consisted primarily of youth with bipolar disorders, lack of variability may have limited this finding. Thus, some interesting and unexpected findings in the current study highlight considerations for clinical practice and inform areas of future research.

Implications for Research, Policy, and Practice

This study has important implications regarding effective treatment of childhood mood disorders. Findings emphasize the importance of comprehensive assessment prior to treatment initiation. Regarding prognostic indicators, low functioning youth with stress/trauma histories and parents with low levels of Cluster B personality disorder symptoms may fare well with TAU and MF-PEP; however, additional and/or different interventions may be required for higher functioning youth without stress/trauma histories and with parents with high levels of Cluster B personality disorder symptoms. For children with severe global impairment, psychoeducational interventions, such as MF-PEP, may be especially effective and more impactful than available treatments.

These findings also lend support for currently employed treatments (i.e., TAU) and psychoeducational interventions (i.e., MF-PEP) in treatment of childhood mood disorders, regardless of various demographic, youth, parental, and family functioning pretreatment characteristics. For example, in this study, treatment response was unaffected by children’s demographic status, cognitive abilities, and mood diagnosis, parents’ general psychiatric and mood symptoms, and familial expressed emotion. Though somewhat surprising, these findings are promising and suggest that positive treatment response may not be impeded by these variables. Thus, while thorough assessment evaluating all aforementioned variables is necessary to inform treatment, attention to children’s stress/trauma histories and functional impairment, and parental psychopathology (particularly Cluster B personality disorder symptoms), may be especially important to consider when selecting effective treatment for childhood mood disorders.

Regarding MF-PEP in particular, the content and format are effective for children with varied demographics, comorbidities, familial and parental backgrounds, and functioning. In fact, MF-PEP may be most effective for the most impaired children. Thus, psychoeducational treatments and other family-based interventions are likely to be applicable and beneficial in clinical settings.

Limitations

Limitations relate to the sample, measured variables, design, and assessment instruments. The sample lacked diversity (73% male and 90% White, non-Hispanic), and therefore may not be representative of the population of children with mood disorders. In addition, characteristics of families who seek clinical trials may differ from those in a general clinic sample. In particular, although parents in the current study reported a robust history of mood symptoms, their symptom severity at baseline was not notable. Thus, these parents may have been more resourceful in acquiring services for themselves and their children, and may have been more stable and capable at the time of the study. Also, greater diversity in the sample may have revealed demographic variables as predictors and moderators. Similarly, other variables such as resiliency, coping strategies, communication skills, and other indicators of severity (i.e., suicidality, hopelessness) may be important predictors or moderators of treatment, but were not specifically measured. Thus, research including diverse samples in general practice settings and measurement of other potentially important variables that may affect outcome is needed.

Attrition at follow-up assessments limited statistical power. Thus, the mood symptom severity of the sample analyzed at later time points may not be representative of the original sample and therefore may have produced biased results. In addition, MF-PEP+TAU was compared to WLC+TAU, rather than to a placebo or another uniquely active treatment; therefore, conclusions cannot be drawn about the specific components of MF-PEP compared to other interventions. Additionally, most measures of examined predictors and moderators relied solely on parent report (with the exception of stress/trauma), which may have been problematic for parents suffering from psychopathology. Parents with emotional or behavioral disturbance may have had impaired judgment in reporting their child’s or their own symptoms, potentially affecting predictor and moderator findings. Thus, future research containing additional semi-structured assessments, incorporating information from multiple informants, may provide more unbiased measurement of variables of interest. Despite these limitations, this study provides important findings regarding treatment of childhood mood disorders and indicates areas in need of further research.

Conclusions

Comprehensive evaluation should be conducted prior to treatment of childhood mood disorders. Clinicians should especially consider children’s stress/trauma history and global functioning, as well as parental psychopathology. Specifically, youth with high global functioning, without stress/trauma history, and with parents with high levels of Cluster B personality disorder symptoms may fare more poorly in both MF-PEP and currently offered treatments, and thus may require additional and/or different interventions. In addition, youth with severe functional impairment may experience the most benefit in mood symptoms from psychoeducational interventions, such as MF-PEP. Thus, findings support the use of thorough pretreatment assessments to inform prognostic indicators and guide intervention selection, as well as implementation of family-based psychoeducational treatments in practice settings, given the demonstrated efficacy of MF-PEP for impaired children’s mood symptoms, regardless of children’s demographic status, cognitive abilities, and mood diagnosis, parents’ general psychiatric and mood symptoms, and familial expressed emotion.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by a grant to Mary A. Fristad from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH R01MH061512).

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest: Dr. Fristad is the author of a treatment manual (Guilford Press, Inc.) and MF-PEP workbooks (www.moodychildtherapy.com) for which she receives royalties.

Contributor Information

Heather A. MacPherson, Email: heather.macpherson@osumc.edu, Departments of Psychiatry and Psychology, The Ohio State University, 1670 Upham Dr, Ste 460, Columbus, OH 43210.

Guillermo Perez Algorta, Email: guillermo.perezalgorta@osumc.edu, Departments of Psychiatry and Psychology, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 46210.

Amy N. Mendenhall, Email: amendenhall@ku.edu, School of Social Welfare, The University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS.

Benjamin W. Fields, Email: benjamin.fields@nationwidechildrens.org, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH.

Mary A. Fristad, Email: mary.fristad@osumc.edu, Departments of Psychiatry and Psychology, The Ohio State University – Psychiatry, 1670 Upham Dr, Columbus, OH 43210.

References

- Asarnow JR, Emslie G, Clarke G, Wagner KD, Spirito A, Vitiello B, Brent D. Treatment of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-resistant depression in adolescents: Predictors and moderators of treatment response. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:330–339. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181977476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbe RP, Bridge J, Birmaher B, Kolko D, Brent DA. Suicidality and its relationship to treatment outcome in depressed adolescents. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2004a;34:44–55. doi: 10.1521/suli.34.1.44.27768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbe RP, Bridge J, Birmaher B, Kolko DJ, Brent DA. Lifetime history of sexual abuse, clinical presentation, and outcome in a clinical trial for adolescent depression. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004b;65:77–83. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Brent DA, Kolko D, Baugher M, Bridge J, Holder D, Ulloa RE. Clinical outcome after short-term psychotherapy for adolescents with major depressive disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:29–36. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boylan K, MacPherson HA, Fristad MA. Examination of disruptive behavior outcomes and moderation in a randomized psychotherapy trial for mood disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. in press doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Kolko DJ, Birmaher B, Baugher M, Bridge J. A clinical trial for adolescent depression: Predictors of additional treatment in the acute and follow-up phases of the trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:263–270. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199903000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Kolko DJ, Birmaher B, Baugher M, Bridge J, Roth C, Holder D. Predictors of treatment efficacy in a clinical trial of three psychosocial treatments for adolescent depression. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37:906–914. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199809000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke G, Hops H, Lewinsohn PM, Andrews J, Seeley JR, Williams J. Cognitive-behavioral group treatment of adolescent depression: Prediction of Outcome. Behavior Therapy. 1992;23:341–354. [Google Scholar]

- Coddington RD. Life Events Scale for Children and Adolescents: Measuring the stressfulness of a child's environment. In: Humphrey JH, editor. Stress in Childhood. New York, NY: AMS Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings CM, Fristad MA. Anxiety in children with mood disorders: A treatment help or hindrance? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2012;45:339–351. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9568-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry J, Rohde P, Simons A, Silva S, Vitiello B, Kratochvil C, March J. Predictors and moderators of acute outcome in the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:1427–1439. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000240838.78984.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry J, Silva S, Rohde P, Ginsburg G, Kratochvil C, Simons A, March J. Recovery and recurrence following treatment for adolescent major depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68:263–269. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David-Ferdon C, Kaslow NJ. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:62–104. doi: 10.1080/15374410701817865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekselius L, Lindström E, von Knorring L, Bodlund O, Kullgren G. SCID II interviews and the SCID Screen questionnaire as diagnostic tools for personality disorders in DSM-III-R. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1994;90:120–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emslie GJ, Mayes T, Porta G, Vitiello B, Clarke G, Wagner KD, Brent D. Treatment of Resistant Depression in Adolescents (TORDIA): Week 24 outcomes. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167:782–791. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09040552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeny NC, Silva SG, Reinecke MA, McNulty S, Findling RL, Rohde P, March JS. An exploratory analysis of the impact of family functioning on treament for depression in adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2009;38:814–825. doi: 10.1080/15374410903297148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Benjamin LS. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personaliyt Disorders (SCID-II) Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann MS, Goldstien MJ. Relatives’ awareness of their own expressed emotion as measured by a self-report adjective checklist. Family Process. 1993;32:459–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1993.00459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fristad MA, Goldberg-Arnold JS, Gavazzi SM. Multifamily psychoeducation groups (MFPG) for families of children with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders. 2002;4:254–262. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2002.09073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fristad MA, Goldberg-Arnold JS, Gavazzi SM. Multi-family psychoeducation groups in the treatment of children with mood disorders. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2003;29:491–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2003.tb01691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fristad MA, Goldberg Arnold JS, Leffler JM. Psychotherapy for children with bipolar and depressive disorders. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fristad MA, MacPherson HA. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent bipolar spectrum disorders. Invited manuscript submitted for publication. 2013 doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.822309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fristad MA, Verducci JS, Walters K, Young ME. The impact of Multi-Family Psychoeducation Groups (MFPG) in treating children aged 8–12 with mood disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:1013–1020. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fristad MA, Weller RA, Weller EB. The Mania Rating Scale (MRS): Further reliability and validity studies with children. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 1995;7:127–132. doi: 10.3109/10401239509149039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg-Arnold JS, Fristad MA, Gavazzi SM. Family psychoeducation: Giving caregivers what they want and need. Family Relations. 1999;48:411–417. [Google Scholar]

- Gunlicks ML, Weissman MM. Change in child psychopathology with improvement in parental depression: A systematic review. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47:379–389. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181640805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunlicks-Stoessel M, Mufson L, Jekal A, Turner JB. The impact of perceived interpersonal functioning on treatment for adolescent depression: IPT-A versus treatment as usual in school-based health clinics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:260–267. doi: 10.1037/a0018935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1967;6:278–296. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1967.tb00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedlund JL, Vieweg BW. The Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression: A comprehensive review. Journal of Operational Psychiatry. 1979;10:149–165. [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP. Intervention research, theoretical mechanisms, and causal processes related to externalizing behavior problems. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14:789–818. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402004078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollon SD, Munoz RF, Barlow DH, Beardslee WR, Bell CC, Bernal G, Sommers D. Psychosocial intervention development for the prevention and treatment of depression: promoting innovation and increasing access. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;52:610–630. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01384-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayson D, Wood A, Kroll L, Fraser J, Harrington R. Which depressed patients respond to cognitive-behavioral treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37:35–39. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199801000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman A, Kaufman N. Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Wilson GT, Fairburn CG, Agras WS. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:877–883. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kratochvil CJ, May DE, Silva SG, Madaan V, Puumala SE, Curry JF, March JS. Treatment response in depressed adolescents with and without co-morbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2009;19:519–527. doi: 10.1089/cap.2008.0143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leichsenring F, Leibing E, Kruse J, New AS, Leweke F. Borderline personality disorder. Lancet. 2011;377:74–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61422-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis CC, Simons AD, Nguyen LJ, Murakami JL, Reid MW, Silva SG, March JS. Impact of childhood trauma on treatment outcome in the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49:132–140. doi: 10.1097/00004583-201002000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maffei C, Fossati A, Agostoni A, Barraco A, Bagnato M, Deborah D, Petrachi M. Interrater reliability and internal consistency of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II personality disorders (SCID-II), version 2.0. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1997;11:279–284. doi: 10.1521/pedi.1997.11.3.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendenhall AN, Fristad MA, Early TJ. Factors influencing service utilization and mood symptom severity in children with mood disorders: Effects of multifamily psychoeducation groups (MFPGs) Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:463–473. doi: 10.1037/a0014527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DJ, Axelson DA, George EL, Taylor DO, Schneck CD, Sullilvan, Birmaher B. Expressed emotion moderates the effects of family-focused treatment for bipolar adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:643–651. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181a0ab9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanni V, Uher R, Danese A. Childhood maltreatment predicts unfavorable course of illness and treatment outcome in depression: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;169:141–151. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11020335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemeroff CB, Heim CM, Thase ME, Klein DN, Rush AJ, Schatzberg AF, Keller MB. Differential responses to psychotherapy versus pharmacotherapy in patients with chronic forms of major depression and childhood trauma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:14293–14296. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2336126100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK. Progress review of psychosocial treatment of child conduct problems. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2003;10:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Othmer E, Penick EC, Powell BJ, Read MR, Othmer SC. Psychiatric Diagnostic Interview – Revised (PDI-R). Administration Booklet and Manual. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Paul G. Outcome research in psychotherapy. Journal of Consulting Psychology. 1967;31:109–118. doi: 10.1037/h0024436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poznanski EO, Grossman JA, Buchsbaum Y, Banegas M, Freeman L, Gibbons R. Preliminary studies of the reliability and validity of the Children's Depression Rating Scale. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry. 1984;23:191–197. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198403000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Clarke GN, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Kaufman NK. Impact of comorbidity on a cognitive-behavioral group treatment for adolescent depression. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:795–802. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200107000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Seeley JR, Kaufman NK, Clarke GN, Stice E. Predicting time to recovery among depressed adolescents treated in two psychosocial group interventions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:80–88. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.1.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Multiple imputation after 18+ years. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1996;91:473–489. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, Ambrosini P, Fisher P, Bird H, Aluwahlia S. A Children's Global Assessment Scale (CGAS) Archives of General Psychiatry. 1983;40:1228–1231. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790100074010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamseddeen W, Asarnow JR, Clarke G, Vitiello B, Wagner KD, Birmaher B, Brent DA. Impact of physical and sexual abuse on treatment response in the Treatment of Resistant Depression in Adolescent Study (TORDIA) Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50:293–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurrence. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Vitiello B, Emslie G, Clarke G, Wagner KD, Asarnow JR, Keller M, Brent D. Long-term outcome of adolescent depression initially resistant to SSRI treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2011;72:388–396. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05885blu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller EB, Weller RA, Fristad MA, Rooney MT, Schecter J. Children’s Interview for Psychiatric Syndromes. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:76–84. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller EB, Weller RA, Rooney MT, Fristad MA. Children’s Interview for Psychiatric Syndromes (ChIPS) Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1999a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller EB, Weller RA, Rooney MT, Fristad MA. Children’s Interview for Psychiatric Syndromes, Parent Version (P-ChIPS) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1999b. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson P, Dubicka B, Kelvin R, Roberts C, Goodyer I. Treated depression in Adolescents: Predictors of outcome at 28 weeks. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;194:334–341. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.052381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: Reliability, validity, and sensitivity. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1978;133:429–435. doi: 10.1192/bjp.133.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngstrom EA, Danielson CK, Findling RL, Gracious BL, Calabrese JR. Factor structure of the Young Mania Rating Scale for use with youths ages 5 to 17 years. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31:567–572. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3104_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]