Abstract

Background

Examining the natural language college students use to describe various levels of intoxication can provide important insight into subjective perceptions of college alcohol use. Previous research (Levitt et al., 2009) has shown that intoxication terms reflect moderate and heavy levels of intoxication, and that self-use of these terms differs by gender among college students. However, it is still unknown whether these terms similarly apply to other individuals and, if so, whether similar gender differences exist.

Method

To address these issues, the current study examined the application of intoxication terms to characters in experimentally manipulated vignettes of naturalistic drinking situations within a sample of university undergraduates (N = 145).

Results

Findings supported and extended previous research by showing that other-directed applications of intoxication terms are similar to self-directed applications, and depend on the gender of both the target and the user. Specifically, moderate intoxication terms were applied to and from women more than men, even when the character was heavily intoxicated, whereas heavy intoxication terms were applied to and from men more than women.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that gender differences in the application of intoxication terms are other-directed as well as self-directed, and that intoxication language can inform gender-specific prevention and intervention efforts targeting problematic alcohol use among college students.

Keywords: gender differences, subjective intoxication, language, alcohol, college students

The natural language that drinkers use to describe intoxicated states is an important and understudied area of alcohol research. Understanding this language can provide critical insight into subjective perceptions of intoxicated states, particularly among specific groups in the general drinking population such as college students that demonstrate elevated levels of heavy episodic drinking and alcohol-related consequences. However, little research has examined the usage of this natural language (e.g., Cameron et al., 2000; Levine, 1981), and much of it has been limited to qualitative examinations. Only one study has quantitatively examined the usage of these terms at varying levels of intoxication.Levitt et al. (2009) recently found in an online survey study of college students that intoxication terms familiar to and commonly self-used by students reflected two factors of moderate and heavy intoxication. Furthermore, gender differences were found in the use of these two factors. Women reported that they were more likely to use moderate terms (e.g., “tipsy,” “buzzed”) to describe themselves, even at heavy episodic drinking levels (i.e., 4–5 drinks over 2 hours). In contrast, men were more likely to self-use heavy terms (e.g., “wasted,” trashed”) to describe themselves. Additionally, the term “drunk” did not differentiate between moderate and heavy levels of intoxication, supporting the notion that being “drunk” is defined by a complex set of expected and experienced subjective effects (Midanik, 2003; Ray et al., 2009; Reich et al., 2012) and varies by individual differences in the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of alcohol (Sher and Wood, 2005; Sher et al., 2005). Accounting for multiple natural language intoxication terms can not only provide more detailed information about individuals’ perceptions of subjective intoxication, but can also do so more succinctly by acting as a reflective summary of individuals’ expected or experienced indicators of intoxication.

The study byLevitt et al. (2009), however, focused only on students’ self-directed application of intoxication terms. Thus, it is unclear whether the usage of intoxication terms similarly applies externally to other individuals, and if so, whether similar gender differences exist in other-directed applications of intoxication terms. The current study examined these issues in a sample of college students using experimentally manipulated vignettes of naturalistic drinking situations in which participants applied intoxication terms to the main character in the vignette.

Understanding subjective intoxication in college students is of critical importance considering that heavy episodic drinking is prominent among college students. A significant amount of research demonstrates that college students are at risk of experiencing a number of severe problems as consequences of alcohol misuse (Dowdall and Wechsler, 2002; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2007; O’Malley and Johnston, 2002; Perkins, 2002; Turrisi et al., 2006). Furthermore, research suggests that rates of alcohol use prevalence (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2012) and heavy episodic drinking (O’Malley and Johnston, 2002) are becoming more similar between women and men in the years leading up to and in college. A consequence of this increased usage among women is recent increases in alcohol-related problems among women such as alcohol abuse and dependence diagnoses (Slutske, 2005) and verbal, physical, and sexual aggression associated with heavy alcohol use (Parks et al., 2008). In part, these changes in female student drinking and related problems over recent years may reflect women’s misperceptions of how much their peers (especially male peers) expect them to drink (LaBrie et al., 2009) as well as underestimation of how intoxicated they are while drinking (Grant et al., 2012; Mallett et al., 2009). Underestimation of one’s own intoxication places individuals at increased risk for alcohol-related consequences (e.g., drunk driving; Marczinski & Fillmore, 2009). Misperception of others’ intoxication is similarly associated with increased alcohol-related consequences for those individuals. For example, research indicates that training alcohol servers to correctly perceive and identify intoxication in patrons is associated with decreased drunk driving among those patrons (Holder & Wagenaar, 1994). Taken together, this research highlights the importance of better understanding college students’ subjective perceptions of intoxication, and particularly gender differences in these perceptions.

Understanding how college students use intoxication language to describe other students as well as themselves (Levitt et al., 2009) is also important considering that college reflects a period of increased social drinking, particularly as descriptive and injunctive norms about drinking behavior and its effects are communicated verbally between friends and other students. For instance, consider two hypothetical conversations between students: (1) “Are you good to drive?” “Yeah, I’m just tipsy,” and (2) “Did you go to that party last night?” “Yeah, it was awesome! Everyone was wasted!” Both of these conversations reflect potentially risky situations in which (1) risky decision making and impaired driving may be dismissed or downplayed by using a moderate intoxication term (italicized), and (2) heavy episodic drinking, as reflected by a heavy intoxication term (italicized), is communicated as descriptively and injunctively normative (Borsari & Carey, 2003). Furthermore, based on our previous work showing gender differences in the self-use of intoxication terms (Levitt et al., 2009), situation (1) above may be particularly relevant to female students, whereas situation (2) may be more relevant to male students.

The Current Study

The current study seeks to extend previous research (Levitt et al., 2009) by assessing how college students apply intoxication terms to characters in hypothetical vignettes of naturalistic drinking situations in which the character’s gender, intoxication level, and aggressive behaviors are experimentally manipulated. To the extent that gender differences in other-directed use of intoxication terms are similar to differences found previously in self-use of intoxication terms, and based on related literature reviewed above, we hypothesized that:

H1) participants would apply moderate intoxication terms more to female characters than male, even if female characters were heavily intoxicated, but not necessarily aggressive;

H2) participants would apply heavy intoxication terms more to male characters than female, especially when male characters were heavily intoxicated and/or aggressive; and

H3) participants’ gender would moderate the expected effects in H1 and H2 such that the expected differences in the application of moderate intoxication terms for female characters (H1) would be stronger among female participants than male, whereas the expected differences in the application of heavy intoxication terms for male characters (H2) would be stronger among male participants than female.

Method

Participants and Procedure

A sample of 145 undergraduate students from a large Midwestern university participated in the study during the Spring semester of 2007. Participants were evenly split in gender (50% male), mostly Caucasian (90%), and ranged in age from 17 to 22 years (M = 19.1 years), with 29% reporting being in a Greek fraternity or sorority. Participants reported an average Q/F of 10.07 (SD = 11.17) drinks per week over the past year, and 2 occasions of heavy drinking (i.e., drinking 5+ drinks in one sitting and drinking to intoxication) over the past month, with most participants (47%) considering themselves “moderate” drinkers. These rates of alcohol involvement, which are comparable to those found in other studies of college students (e.g., Mallett et al., 2009), are only presented as descriptive information for our sample and were not used in analyses.

As part of a larger online survey study on the natural language of intoxication (see Levitt et al., 2009, for details), participants were randomly assigned to read one of eight vignette conditions in their survey. The number of participants in each cell ranged from 16–19, with participant gender being equal within vignette conditions. The university institutional review board approved the current study, and participants granted informed consent electronically before completing the survey. Participants received partial course credit as compensation for completing the survey.

Measures

Vignettes

Common to all vignettes was the depiction of a naturalistic drinking situation in which the main character goes to a bar with a mixed-gender group of four friends to celebrate the character’s birthday. Three factors were manipulated between vignettes: (1) character gender (male [described as 5’10” tall, 170 lbs.] vs. female [described as 5’4” tall, 130 lbs.]), (2) character intoxication level (moderate [i.e., 7 beers over 3 hours for male characters; 4.5 beers over 3 hours for female characters; target estimated BAL = ~.11 for both male and female characters] vs. heavy [i.e., 9 beers and 2 shots of liquor over 3 hours for male characters; 5 beers and 2 shots of liquor over 3 hours for female characters; target BAL = ~.20 for both male and female characters]), and (3) character aggression level (aggressive [i.e., verbal aggression towards friends once intoxicated] vs. non-aggressive [i.e., being playful with friends and flirting with an opposite sex friend]).

Language of intoxication terms

The applicability of intoxication terms to characters in vignettes served as the outcome in the current study. Participants rated how much each term applied to the main character in their assigned vignette on a scale of 1 (“Doesn’t apply at all”) to 5 (“Definitely applies”). Two composite variables of the applicability of moderate (i.e., “buzzed,” “light-headed,” “loopy,” “tipsy;” 4 items; average α within vignette condition = .74) or heavy (i.e., “fucked up,” “gone,” “hammered,” “obliterated,” “plastered,” “plowed,” “shit-faced,” “smashed,” “tanked,” “trashed,” “wasted;” 11 items; average α within vignette condition = .97) intoxication were created as dependent variables. These two factors of items were chosen based on previous factor analyses, and descriptive analyses demonstrating that these terms are commonly understood and self-referentially used among college-aged individuals (Levitt et al., 2009). It should also be noted that these outcome factors were not positively correlated (r = −.09, p = .30) with one another indicating that individuals likely use either only moderate or heavy intoxication terms when describing a specific intoxicated state, not both.

Data Analyses

Due to missing data on the outcome measures for six participants, the current analyses are based on an n of 139. All models were tested as full factorial ANOVAs in SPSS (2010). To test H1 and H2, separate 2 (character gender; male vs. female) X 2 (character intoxication level; moderate vs. heavy) X 2 (character aggression level; aggressive vs. non-aggressive) full factorial ANOVAs were conducted predicting the applicability of moderate and heavy intoxication terms, respectively, to the vignette character. To test H3, participant gender was included as an additional factor such that separate 2 (participant gender) X 2 (character gender) X 2 (character intoxication level) X 2 (character aggression level) full factorial ANOVAs were conducted predicting the applicability of moderate and heavy intoxication terms, respectively, to the vignette character. Follow-up contrasts were tested based on hypotheses and visual inspection of interaction figures.

Results

H1: Applicability of Moderate Intoxication Terms to Female Vignette Characters

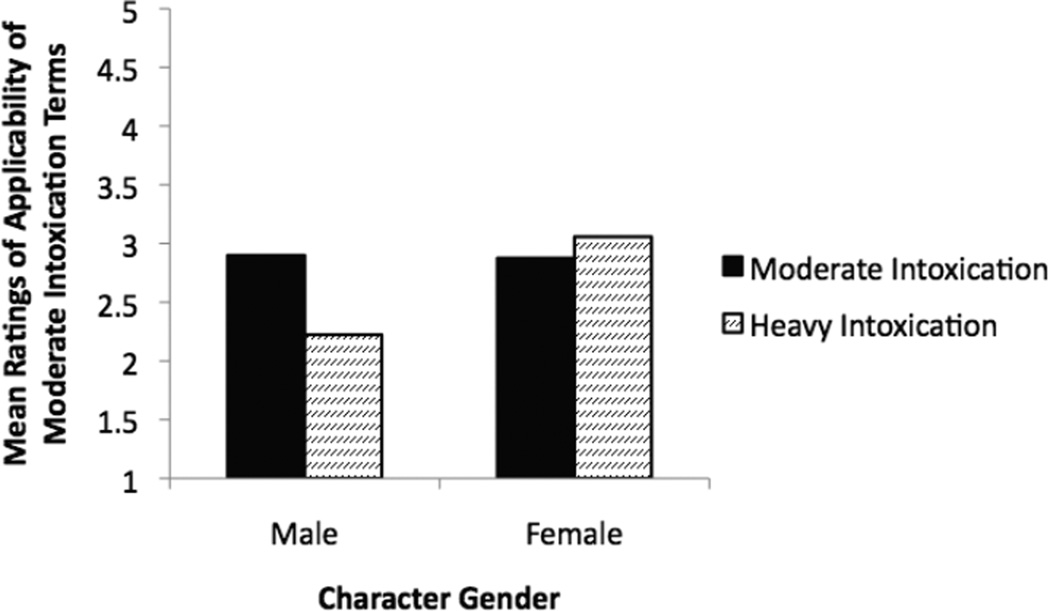

As expected, a significant main effect was found for character gender (F [1, 131] = 4.70, p = .032, partial η2 = .04) such that participants applied moderate intoxication terms more to female characters (M = 2.96, SD = 1.19) compared to male characters (M = 2.55, SD = 1.04). However, also in line with expectation, this effect was moderated by character intoxication level (F [1, 131] = 5.26, p = .023, partial η2 = .04). As shown in Figure 1, follow-up contrasts revealed that no differences were found in the applicability of moderate intoxication terms between male and female characters when the character was moderately intoxicated. Interestingly, however, when the character was heavily intoxicated, participants applied moderate intoxication terms more to female characters compared to male (F [1, 131] = 9.74, p = .002, partial η2 = .07). Whereas participants applied moderate intoxication terms less to male characters when they were heavily compared to moderately intoxicated (F [1, 131] = 6.31, p = .013, partial η2 = .07), no such difference was found for female characters. No other main or interaction effects were significant.

Figure 1.

Character gender X character intoxication level interaction predicting mean ratings of applicability of moderate intoxication terms.

H2: Applicability of Heavy Intoxication Terms to Male Vignette Characters

As expected, a significant main effect was found for character gender (F [1, 131] = 4.68, p = .032, partial η2 = .03) such that participants applied heavy intoxication terms more to male characters (M = 3.14, SD = 1.34) compared to female characters (M = 2.69, SD = 1.41). However, contrary to expectation, this effect was not moderated by either character intoxication level or character aggression level, suggesting that the observed character gender effect did not depend on how much the character drank or how aggressively the character behaved. Main effects were also found for character intoxication level (F [1, 131] = 113.35, p = .000, partial η2 = .46) and character aggression level (F [1, 131] = 6.67, p = .011, partial η2 = .05) such that participants reported that heavy intoxication terms applied more to heavily (M = 3.85, SD = 1.13) vs. moderately (M = 2.00, SD = 0.96) intoxicated characters and aggressive (M = 3.10, SD = 1.36) vs. non-aggressive (M = 2.72, SD = 1.42) characters. No significant interaction effects were found.

H3: Participant Gender Moderation of Intoxication Terms Applicability

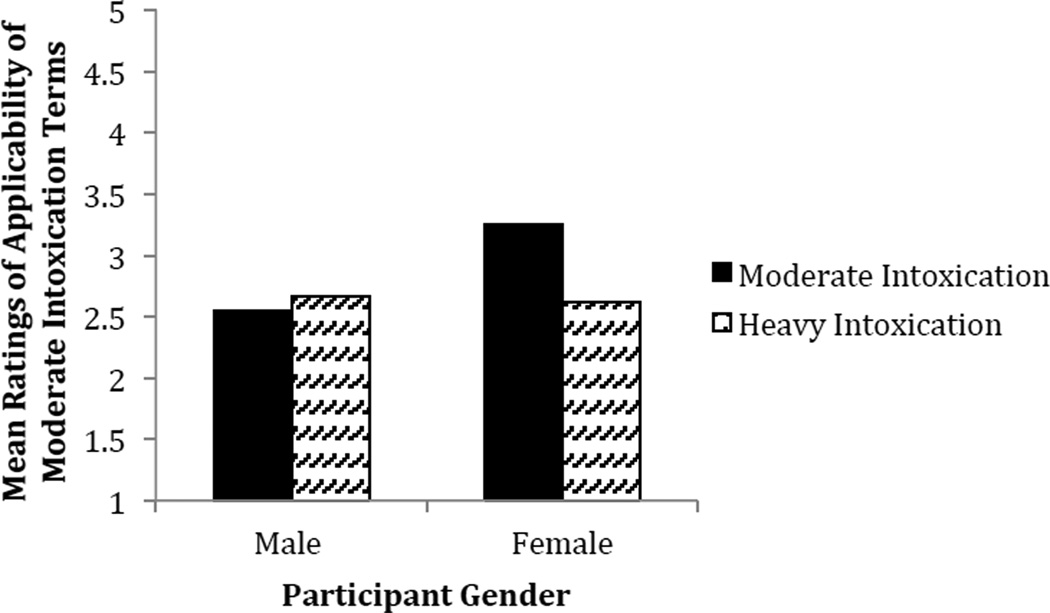

For moderate intoxication terms, a significant participant gender X character intoxication level interaction was found (F [1, 123] =4.28, p = .041, partial η2 = .03). As shown in Figure 2, follow-up contrasts revealed that female participants applied moderate intoxication terms more to moderately intoxicated characters, regardless of character gender, compared to male participants (F [1, 123] = 7.72, p = .006, partial η2 = .06). Female participants also applied moderate intoxication terms more to moderately compared to heavily intoxicated characters (F [1, 123] = 5.96, p = .016, partial η2 = .05), whereas no such difference was found among male participants. Although this moderation effect was not completely as expected in that the effect found for H1 (see Figure 1) would be stronger for female participants, it is consistent with the overall pattern of the current and previous results (Levitt et al., 2009) in that women appear to apply moderate intoxication terms to other individuals more than men.

Figure 2.

Participant gender X character intoxication level interaction predicting mean ratings of applicability of moderate intoxication terms.

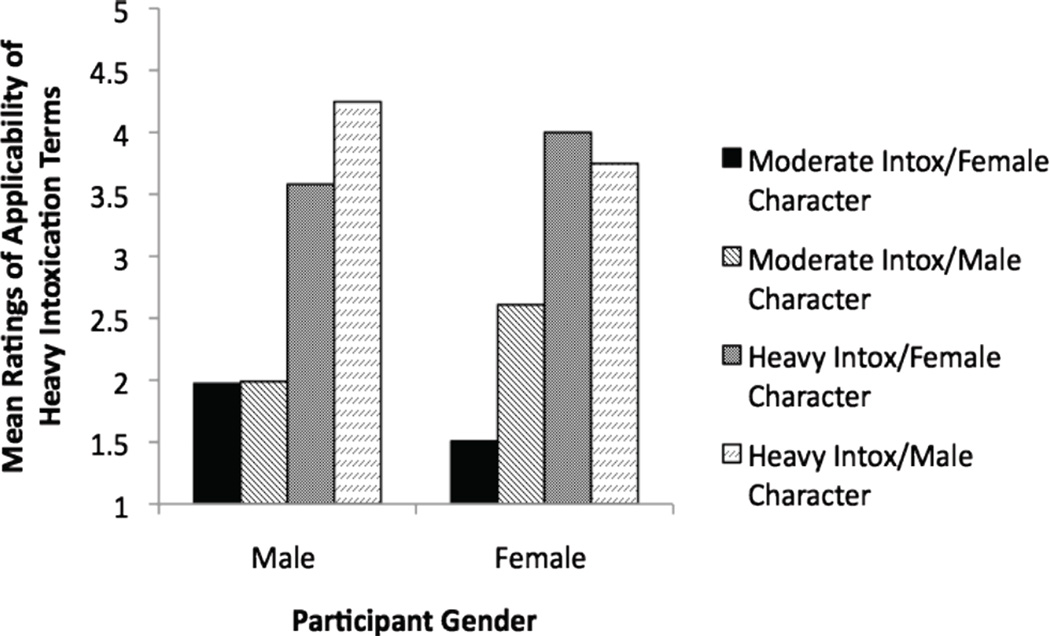

For heavy intoxication terms, a significant participant gender X character gender X character intoxication level interaction was found (F [1, 123] = 8.54, p = .005, partial η2 = .06). As shown in Figure 3, and consistent with expectation, follow-up contrasts revealed a marginal effect such that male participants applied heavy intoxication terms more to heavily intoxicated male characters compared to heavily intoxicated female characters (F [1, 123] = 3.47, p = .065, partial η2 = .03). No such difference was found among female participants. In addition, female participants applied heavy intoxication terms more to moderately intoxicated male characters compared to moderately intoxicated female characters (F [1, 123] = 10.00, p = .002, partial η2 = .08), whereas this difference was not found among male participants. No other follow-up contrasts were significant.1

Figure 3.

Participant gender X character intoxication level X character gender interaction predicting mean ratings of applicability of heavy intoxication terms.

Discussion

The current study examined gender differences in the application of natural language intoxication terms to characters in experimentally manipulated vignettes of naturalistic drinking situations. Results generally supported our hypotheses. Specifically, participants applied moderate intoxication terms (e.g., “tipsy,” “buzzed”) more to female characters than male, particularly when female characters were heavily intoxicated (see Figure 1). In contrast, participants applied heavy intoxication terms (e.g., “wasted,” “trashed”) more to male characters than female, an effect that was independent of other character factors. Differences in effects were also found as a function of raters’ gender. Female participants applied moderate intoxication terms to moderately intoxicated characters more than male participants (see Figure 2). Additionally, male participants applied heavy intoxication terms more to heavily intoxicated male characters compared to heavily intoxicated female characters (see Figure 3).

The current findings support and extend previous research by demonstrating that gender differences in the application of natural intoxication language are similar when the target is external (i.e., other-directed) compared to internal (i.e., self-directed). These findings suggest a number of important implications for research and theory on subjective intoxication in college students (and likely other populations as well). First, the lexicon of intoxication language appears to apply broadly to various intoxicated states of college students and is applied in a similar way to others and the self. In part, this likely reflects the pervasiveness of drinking culture among college students (e.g., Wechsler et al., 2002). That college students intuitively use various terms to represent distinct levels of intoxication implies that they recognize perceptual and behavioral differences among intoxicated states either from their own experience or by observing friends and other students.

Second, within the body of natural intoxication language, the application of moderate vs. heavy intoxication terms depends on the gender of the target as well as the gender of the individual applying the term. Moderate intoxication terms appear to be applied to and from women more than men. This is in line with previous research showing that women prefer more euphemistic slang than men (Haas, 1979). Related to drinking behavior, this usage may reflect social and gender norms for expected behavior among women. Although women perceive that they are expected to drink as much as men in college drinking culture (LaBrie et al., 2009), women may be negatively perceived by both male and female peers when drinking heavily (George et al., 1988). This double standard may lead women to apply moderate intoxication terms to themselves and to other women to downplay their level of intoxication and not violate perceived social and gender norms. However, the fact that women apply euphemistic terms such as “tipsy” even when the target is substantially intoxicated (see Figure 1) is troubling given that such misperceptions of others’ intoxication could lead to the encouragement of poor decision making and the downplaying of risky situations such as driving while impaired, having unplanned sexual activity, being the victim of verbal, physical, or sexual assault, and experiencing other serious alcohol-related problems (Abbey et al., 1998; Fritner & Rubinson, 1993; Parks et al., 2008; Wechsler et al., 2002). Moreover, considering that these terms can be other-directed as well as self-directed suggests that the communication of moderate intoxication terms within groups of heavily intoxicated college women may exacerbate potential risky decision making as a function of groupthink (Kroon et al., 1992). Although these potential associations are intuitive based on related research, they are nevertheless speculative given that the current data does not directly assess risk-taking behaviors. Future research is required to determine whether the inaccurate application of less severe intoxication language is actually a risk factor for one’s own or others’ behaviors following drinking.

In contrast, heavy intoxication terms appear to be applied to and from men more than women. This in part likely reflects the fact that college men drink more frequently and more heavily than college women (Chen et al., 2004/2005). It could also reflect the tendency for college men to overestimate the normative drinking behaviors of male peers (Larimer et al., 2011). In other words, to some extent heavy drinking might simply be a characteristic component of what constitutes the college male gender role. Such an interpretation would be consistent with the results of the current study including that the main effect of character male gender on the application of heavy intoxication terms was not moderated by character intoxication or aggression levels. Regardless, to the extent that college men use heavy intoxication terms such as “wasted” to represent a positive experiential state as opposed to simply a literal description may potentially communicate to other friends and students that heavy episodic drinking is not only the norm but also safe and encouraged. This is concerning in light of recent reports showing increased rates of severe problems resulting from heavy episodic drinking among college students including alcohol poisoning and drunk driving (Hingson et al., 2009).

Gender differences in the use of intoxication language may also have implications for gender-specific alcohol prevention and intervention efforts among college students. Personalized normative feedback of college students’ drinking behaviors is most effective when the feedback is gender-specific compared to gender-neutral (Lewis et al., 2007) considering that college students use gender-specific norms of typical drinking behavior, and that within-gender norms are associated more with alcohol problems than between-gender norms (Lewis & Neighbors, 2004). The current results support previous research (Levitt et al., 2009) showing that women use more moderate intoxication language, whereas men use more heavy intoxication language. This information may inform gender-specific personalized normative feedback so that prevention and intervention efforts targeting college student alcohol use can be more tailored by using language that college students use themselves.

Limitations and Future Directions

Despite some notable strengths, it is not without limitations. First, despite our consistent and valid findings, the current study utilized an online survey methodology, which limits experimenter control over the data collection context. However, there is no plausible reason to expect that this method exerted a systematic bias on our findings. Additionally, although the current findings demonstrate further validation for the use of natural language intoxication terms in research on college alcohol use, they were limited to hypothetical drinking situations. Future research needs to examine not only how specific intoxication terms map onto the blood alcohol curve using a controlled laboratory paradigm, but also how terms are used toward self and others in real life drinking situations using observational or ecological momentary assessment methods.

Furthermore, although there is sufficient evidence in our results to suggest that participants correctly perceived the intoxication levels of the vignette characters (based on behavioral indicators and gender-specific dosing) as the researchers intended, due to the nature of the study design, it is impossible to definitively conclude that the applicability of intoxication terms were directly because of participants’ perceptions of the character’s intoxication level. A plausible alternative explanation, particularly concerning gender differences found in the applicability of moderate vs. heavy terms, is because female characters consumed lower absolute numbers of drinks compared to male characters. That is, the current study design did not directly test within-subject variation in alcohol consumption conditions within gender. Although this interpretation cannot explain all gender differences found in the current study, the design and data of current study precludes us from ruling out this possibility.

It is also unknown whether the application of intoxication terms would similarly apply if participants were intoxicated themselves. Risk from incorrectly estimating intoxication (e.g., Holder & Wagenaar, 1994) based on a verbally described state could be exacerbated if the perceiver is similarly intoxicated compared to the target. However, it should be noted that situations could still arise where a sober (or relatively less intoxicated) individual applies an underestimated descriptor (e.g., tipsy) to a target that could have equally risky implications (e.g., letting the “tipsy” person drive) regardless of their own level of intoxication. Of course, any conclusions about potential risk as a function of inaccurately applying natural intoxication language are speculative until assessed directly in future research. As such, future research on potential risk following misperceptions of one’s own or others’ intoxication among college students should take into account the natural language terms students use to describe themselves and others as well as whether the perceiver is intoxicated vs. sober.

An additional limitation concerns the homogeneity of our sample. Although examining factors associated with intoxication and problematic drinking among college students is of critical importance, it is nevertheless uncertain whether the current results generalize to non-college-attending emerging adults (Cleveland, Mallett, White, Turrisi, Favaro, 2013; Slutske, 2005) or to age ranges beyond emerging adulthood, where self-labeling of intoxication may differ (Kerr et al., 2006). Our sample was also limited in regional and cultural variation. Natural intoxication language can differ regionally as well as internationally, even within the English language (Cameron et al., 2000). Future research should examine natural intoxication language periodically across various populations, cultures, and periods throughout the lifespan.

In conclusion, the current study further demonstrates that natural language factors of subjective intoxication are a valid way to identify and succinctly describe distinct levels of intoxication for other individuals as well as oneself. Importantly, the use of these factors differs depending on both the gender of the user and the gender of the target. Such differences have implications for research and theory on gender difference in the effects of college student drinking, and can be applied to improving our understanding of alcohol-related consequences among college students. The current study is an important step toward utilizing natural intoxication language in research and practice both within and beyond college student populations.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grants K05-AA017242 and T32-AA013526 awarded to Kenneth J. Sher. Preparation of this manuscript was partially supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grant T32-AA007583 awarded to the Research Institute on Addictions, University at Buffalo, SUNY. The authors would like to thank Dr. R. Lorraine Collins for her comments during the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Alternative analyses were also considered with intoxication terms treated as a repeated measures factor (2 level: moderate vs. heavy). However, because power calculations revealed that our sample size was underpowered to test such a large 5-way omnibus test (i.e., 2 [character gender] X 2 [character alcohol level] X 2 [character aggression level] X 2 [participant gender] X 2 [intoxication term factor]), and because of concerns with ease of interpretation of results from such a model, we elected to analyze and present the most parsimonious models and contrasts related to our a priori hypotheses.

Contributor Information

Ash Levitt, Research Institute on Addictions, University at Buffalo, SUNY

Robert C. Schlauch, Research Institute on Addictions, University at Buffalo, SUNY

Bruce D. Bartholow, University of Missouri and the Midwest Alcoholism Research Center

Kenneth J. Sher, University of Missouri and the Midwest Alcoholism Research Center

References

- Abbey A, McAuslan P, Ross LT. Sexual assault perpretration by college men: the role of alcohol, misperception of sexual intent, and sexual beliefs and experiences. J Social Clin Psychol. 1998;17:167–195. [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: a metaanalytic integration. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2003;64:331–341. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron D, Thomas M, Madden S, Thornton C, Bergmark A, Garretsen H, Terzidou M. Intoxicated across Europe: in search of meaning. Addict Res. 2000;8:233–242. [Google Scholar]

- Chen CM, Dufour MC, Yi H. Alcohol consumption among young adults ages 18–24 in the United States: results from the 2001–2001 NESARC survey. Alcohol Res Health. 2004/2005;28:269–280. [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland MJ, Mallett KA, White HR, Turrisi R, Favero S. Patterns of alcohol use and related consequences in non-college-attending emerging adults. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2013;74:84–93. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowdall GW, Wechsler H. Studying college alcohol use: widening the lens, sharpening the focusJStud. Alcohol Suppl. 2002;14:14–22. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frintner MP, Rubinson L. Acquaintance rape: the influence of alcohol, fraternity membership, and sports team membership. J Sex Educ Ther. 1993;19:272–284. [Google Scholar]

- George WH, Gournic SJ, McAfee MP. Perceptions of postdrinking female sexuality: effects of gender, beverage choice, and drink payment. J Appl Social Psychol. 1988;18:1295–1317. [Google Scholar]

- Grant S, LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Lac A. How drunk am I? misperceiving one’s level of intoxication in the college drinking environment. Psychol Addict Behav. 2012;26:51–58. doi: 10.1037/a0023942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas A. Male and female spoken language differences: stereotypes and evidence. Psychol Bull. 1979;86:615–626. [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Zha W, Weitzman ER. Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24, 1998–2005. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;16(Suppl.):12–20. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holder HD, Wagenaar AC. Mandated server training and reduced alcohol-involved traffic crashes: A time series analysis of the Oregon experience. Accident Anal Prev. 1994;26:89–97. doi: 10.1016/0001-4575(94)90071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2011. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr WC, Greenfield TK, Midanik LT. How many drinks does it take you to feel drunk? trends and predictors for subjective drunkenness. Addiction. 2006;101:1428–1437. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroon MBR, Van Kreveld D, Rabbie JM. Group versus individual decision making: effects of accountability and gender on groupthink. Small Group Res. 1992;23:427–458. [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Sail J, Hummer JF, Lac A, Neighbors C. What men want: the role of reflective opposite-sex normative preferences in alcohol use among college women. Psychol Addict Behav. 2009;23:157–162. doi: 10.1037/a0013993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Neighbors C, LaBrie JW, Atkins DC, Lewis MA, Lee CM, Kilmer JR, Kaysen DL, Pedersen ER, Montoya H, Hodge K, Desai S, Hummer JF, Walter T. Descriptive drinking norms: for whom does reference group matter. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2011;72:833–843. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine HG. The vocabulary of drunkenness. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1981;42:1038–1051. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1981.42.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt A, Sher KJ, Bartholow BD. The language of intoxication: preliminary investigations. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:448–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00855.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C, Oster-Aaland L, Kirkeby BS, Larimer ME. Indicated prevention for incoming freshmen: personalized normative feedback and high-risk drinking. Addict Behav. 2007;32:2495–2508. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C. Gender-specific misperceptions of college student drinking norms. Psychol Addict Behav. 2004;18:334–339. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallett KA, Turrisi R, Larimer ME, Mastroleo NR. Have I had one drink too many? assessing gender differences in misperceptions of intoxication among college students. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70:964–970. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marczinski CA, Fillmore MT. Acute alcohol tolerance on subjective intoxication and simulated driving performance in binge drinkers. Psychol Addict Behav. 2009;23:238–247. doi: 10.1037/a0014633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midanik LT. Definitions of drunkenness. Subst Use Misuse. 2003;38:1285–1303. doi: 10.1081/ja-120018485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. What colleges need to know now: and update on college drinking research, NIH Publication No. 07-5010. Bethesda MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Epidemiology of alcohol and other drug use among American college students. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;14(Suppl):23–29. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks KA, Hsieh YP, Bradizza CM, Romosz AM. Factors influencing the temporal relationship between alcohol consumption and experiences with aggression among college women. Psychol Addict Behav. 2008;22:210–218. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins WH. Surveying the damage: a review of research on consequences of alcohol misuse in college populations. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;14(Suppl.):23–39. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray LA, MacKillop J, Leventhal A, Hutchison KE. Catching the alcohol buzz: an examination of the latent factor structure of subjective intoxication. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:2154–2161. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01053.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich RR, Ariel I, Darkes J, Goldman MS. What do you mean“drunk”? convergent validation of multiple methods of mapping alcohol expectancy memory networks. Psychol Addict Behav. 2012 Jan 30; doi: 10.1037/a0026873. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Wood MD. In: Subjective effects of alcohol II, in Mind-altering drugs: the science of subjective experience. Earlywine M, editor. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 135–153. [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Wood MD, Richardson AE, Jackson KM. In: Subjective effects of alcohol I: effects of the drink and drinking context, in Mind-altering drugs: the science of subjective experience. Earlywine M, editor. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 86–134. [Google Scholar]

- Slutske WS. Alcohol use disorders among US college students and their non-collegeattending peers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:321–327. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPSS, Inc. SPSS statistics 19. Chicago, IL: SPSS, Inc.; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Turrisi R, Mallett KA, Mastroleo NR, Larimer ME. Heavy drinking in college students: who is at risk and what is being done about it? J Gen Psychol. 2006;133:401–420. doi: 10.3200/GENP.133.4.401-420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Seibring M, Nelson TF, Lee H. Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts: Findings from 4 Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study Surveys: 1993–2001. J Amer College Health. 2002;50:203–217. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]