Abstract

Accumulating evidence supports the idea that drugs acting at nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) may be beneficial for Parkinson's disease, a neurodegenerative movement disorder characterized by a loss of nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons. Nicotine administration to parkinsonian animals protects against nigrostriatal damage. In addition, nicotine and nAChR drugs improve L-dopa-induced dyskinesias, a debilitating side effect of L-dopa therapy which remains the gold-standard treatment for Parkinson's disease. Nicotine exerts its antidyskinetic effect by interacting with multiple nAChRs. One approach to identify the subtypes specifically involved in L-dopa-induced dyskinesias is through the use of nAChR subunit null mutant mice. Previous work with β2 and α6 nAChR knockout mice has shown that α6β2* nAChRs were necessary for the development/maintenance of L-dopa-induced abnormal involuntary movements (AIMs). The present results in parkinsonian α4 nAChR knockout mice indicate that α4β2* nAChRs also play an essential role since nicotine did not reduce L-dopa-induced AIMs in such mice. Combined analyses of the data from α4 and α6 knockout mice suggest that the α6α4β2β3 subtype may be critical. In contrast to the studies with α4 and α6 knockout mice, nicotine treatment did reduce L-dopa-induced AIMs in parkinsonian α7 nAChR knockout mice. However, α7 nAChR subunit deletion alone increased baseline AIMs, suggesting that α7 receptors exert an inhibitory influence on L-dopa-induced AIMs. In conclusion, α6β2*, α4β2* and α7 nAChRs all modulate L-dopa-induced AIMs, although their mode of regulation varies. Thus drugs targeting one or multiple nAChRs may be optimal for reducing L-dopa-induced dyskinesias in Parkinson's disease.

Keywords: Dyskinesias, Nicotine, Nicotinic receptors, Parkinson’s disease, Striatum

1. Introduction

Parkinson's disease is a progressive neurodegenerative movement disorder characterized by rigidity, tremor and bradykinesia [1–8]. These symptoms arise because of a loss of nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons. Dopamine precursor therapy with L-dopa alleviates many of the parkinsonian motor symptoms; however, abnormal involuntary movements (AIMs) or dyskinesias arise in most patients with extended treatment. These dyskinesias can range from mild to so severe that they interfere with routine functions of daily living. Presently there are few treatment options for L-dopa-induced dyskinesias. Dopamine agonists are used in early Parkinson's disease as these drugs produce fewer dyskinesias, but they are less effective than L-dopa with disease progression. Amantadine is the only clinically approved pharmacological agent for the treatment of L-dopa-induced dyskinesias; however, its effects are limited and diminish with time [9–12]. Deep brain stimulation has proved very successful for some Parkinson's disease patients; however, this is a serious intervention with all the potential adverse effects associated with brain surgery [13, 14]. Extensive research is therefore underway to identify drugs to reduce dyskinesias by targeting CNS neurotransmitter systems directly or indirectly associated with striatal function [1–8]. This includes the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) system which is anatomically and functionally linked to the dopaminergic system [15].

NAChRs, which mediate the action of acetylcholine, are widely expressed in the striatum as well as other brain regions linked to motor function [15]. These ligand-gated ion channels are composed of different combinations of α and β subunits, with the most common subtypes in striatum being α4p2*, α6p2* and α7 nAChRs. The asterisk indicates the possible presence of other subunits in the receptor complex. The populations most prominently expressed on dopaminergic terminals in the striatum, a primary area that degenerates in Parkinson's disease, are the α4β2* and α6β2* nAChRs [15–17]. In addition, α4β2* nAChRs are located on striatal GABAergic neurons [18]. Although expressed at a lower density, α7 nAChRs are also present in the striatum on cortical glutamatergic afferents [19]. Thus there is a rationale for considering that all subtypes may influence functions linked to the nigrostriatal system, such as the development of L-dopa-induced dyskinesias.

Consistent with this idea, previous studies have shown that nicotine reduces L-dopa-induced AIMs in parkinsonian rats, mice and monkeys by 50–70% [20–23]. Nicotine treatment attenuated AIMs when administered by injection, drinking water or minipump, with the latter two readily amenable to use in patients either orally or via a patch. Several lines of evidence indicate that nicotine reduces L-dopa-induced dyskinesias by acting at nAChRs. Varenicline, an agonist that interacts with multiple nAChRs [24–30], decreased L-dopa-induced AIMs in 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA)-lesioned rats by ~50%. The nAChR antagonist mecamylamine ameliorated L-dopa-induced AIMs to a similar extent as nicotine. However, its effects on AIMs were not additive with those of nicotine, further suggesting that nicotine acts at nAChRs [22]. Moreover, 5-iodo-A-85380 (A-85380), an agonist that acts selectively at α4β2* and α6β2* nAChRs, reduced AIMs supporting the idea that the β2* nAChR subtype is important in modulating L-dopa-induced AIMs [31–33].

Further evidence for a role of β2* nAChRs stems from experiments with nAChR null mutant mice, which have thus far focused on β2 and α6 nAChR subunit knockout animals. L-dopa-induced AIMs were lower in β2 nAChR subunit knockout mice with a 6-OHDA lesion compared to wild type [34]. Moreover, nicotine treatment did not reduce AIMs in the knockout mice, indicating that β2* nAChRs were essential [34]. Similar results were observed with α6 nAChR knockout mice suggesting that α6β2* nAChRs are involved in the antidyskinetic effect of nicotine [35].

The present studies were done to investigate whether α4β2* and α7 nAChRs also play a role in L-dopa-induced AIMs. To approach this, we used α4 and α7 nAChR null mutant mice. The results show that α4β2* and α7 nAChRs also regulate AIMs, although in a somewhat different fashion from α6β2* nAChRs and from one another. Thus, drugs targeting α6β2*, α4β2* and/or α7 nAChRs have the potential to influence the occurrence of L-dopa-induced dyskinesias.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

Mice with nAChR subunit null mutations (α4, originally obtained from Dr. John Drago, University of Melbourne, Australia; α7, originally obtained from Dr. Arthur Beaudet, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, USA) were bred onto the C57Bl/6 background for a minimum of 10 generations. They were maintained and produced by heterozygous matings at the Institute for Behavioral Genetics, University of Colorado, Boulder. All care and genotyping procedures were in accordance with the NIH Guide and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Colorado, Boulder. Mice were weaned at 21 days of age and housed 1–5 per cage with same-sex littermates, under a 12 h light/dark cycle with free access to food and water. The mice were genotyped by PCR as previously described [36].

Five wk or more after weaning, the mice were couriered to SRI International, where they were housed 1–5 per cage with same-sex littermates in a temperature- and humidity-controlled environment under a 12 h light/dark cycle with free access to food and water. After an initial acclimation period (2–3 d), the mice were anesthetized with isofluorane (3%) and placed in a Kopf stereotaxic instrument. A burr hole was then drilled through the right side of the skull at the following coordinates relative to Bregma and the dural surface: anteroposterior, −1.2; lateral, − 1.2; ventral, 4.75. The mice next received a unilateral intracranial injection of 3 µg 6-OHDA (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) (in 1 µl) into the medial forebrain bundle to lesion the dopaminergic nigrostriatal pathway, as previously described [35]. Our previous studies show that such a lesion results in ~90% reduction in the striatal dopamine transporter [35]. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at SRI International in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.2. Drug treatment

Nicotine (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was administered via the drinking solution containing 2% saccharin (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The mice were first given only saccharin. Two days later nicotine (free base, 25 µg/ml) was added for 2 days, with the dose increased to 50 µg/ml on day 3, to 100 µg/ml on day 5, to 200 µg/ml on day 8, to a final dose on day 10 of 300 µg/ml (nicotine titration phase), as previously described [34, 35, 37–39].

L-dopa methyl ester (L-dopa) and benserazide hydrochloride were both purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). L-dopa (3 mg/kg) and benserazide (15 mg/kg) were dissolved in saline and injected sc once daily throughout the study, as previously described [34, 35, 40]. Benserazide is an aromatic amino acid decarboxylase inhibitor given to inhibit the breakdown of L-dopa in the periphery.

2.3. Behavioral testing

L-dopa-induced AIMs were rated as described previously [34, 35, 40]. Individual mice were placed in a cylinder and rated every 15 min for 1 min over a 2 h period. Each AIM subtype was scored on a frequency scale from 0 to 4 (0 = no dyskinesia; 1 = occasional dyskinesia displayed for < 50% of the observation time; 2 = sustained dyskinesia displayed for > 50% of the observation time; 3 = continuous dyskinesia; 4 = continuous dyskinesia not interruptible by external stimuli). The animals were also rated on an amplitude scale, consisting of two levels. Level A indicated oral AIMs without tongue protrusion, forelimb AIMs without the shoulder engaged or axial AIMs with body twisting < 60°. Level B indicated oral AIMs with tongue protrusion, forelimb AIMs with the shoulder engaged or axial AIMs with body twisting > 60°. The integrated scores for frequency and amplitude of AIMs used for data analysis were calculated as 1A = 1, 1B = 2, 2A = 2, 2B = 4, 3A = 4, 3B = 6, 4A = 6, 4B = 8. This allowed for scores for any one component (oral, forelimb or axial) to range from 0 to 8, with a maximum possible total score per time point of 24. All rating was done in a blinded fashion.

To evaluate parkinsonism we used the forelimb asymmetry test [34, 35, 41, 42]. Forelimb use was assessed in a plexiglass cage for a 3 min period, with mirrors strategically placed to observe paw movement. Wall exploration was expressed in terms of the % use of the impaired forelimb (contralateral) compared to the total number of limb use movements. All rating was done in a blinded fashion.

2.4. Plasma cotinine levels

Blood (~0.2 ml) was taken from the ocular vein under isofluorane anesthesia and plasma prepared. Cotinine levels were determined throughout the study using an EIA kit (Orasure Technologies, Bethlehem, PA).

2.5. Data analyses

GraphPad Prism (San Diego, CA) was used for statistical analyses. Significance was determined using a Mann-Whitney test or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Bonferroni post hoc test. A level of 0.05 was considered significant. Values are the mean ± SEM of the indicated number of mice.

3. Results

3.1. Studies with α4 nAChR(−/−) and wildtype mice

3.1.1. No change in parkinsonism in α4(−/−) nAChR mice compared to wild type

α4 nAChR knockout and wild type mice were lesioned and treated with nicotine and L-dopa as depicted in the timeline to Fig. 1. Experiments were first done to test whether the absence of α4* nAChRs affected parkinsonism after a unilateral 6-OHDA lesion. No difference was observed in the forelimb asymmetry test between wild type and α4 nAChR subunit knockout mice (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Treatment timeline for α4 nAChR null mutant and wild type mice. All mice were unilaterally lesioned with 6-OHDA. At wk 2, parkinsonism was assessed using the forelimb asymmetry test. One wk later, the mice were injected with L-dopa (3 mg/kg) plus benserazide (15 mg/kg) for the duration of the study. After L-dopa-induced AIMs had stably developed, the mice were given nicotine in the drinking water with the dose gradually increased to 300 µg/ml (nicotine titration phase). The numbers in the white squares represent the wk on nicotine treatment.

Table 1.

Parkinsonian ratings in unilateral 6-OHDA-lesioned wild type and knockout mice. All mice were rated two wk after 6-OHDA lesioning for the forelimb asymmetry test, a measure of unilateral motor dysfunction. Animals were placed in a transparent cage and evaluated over a 3 min period for forepaw placement against the walls of the cage. Each value represents the mean ± SEM of 18–27 mice.

| Genotype | Impaired forelimb use (%) |

|---|---|

| α4 wild type | 30.9 ± 1.1 |

| α4(−/−) | 31.9 ± 2.8 |

| α7 wild type | 31.5 ± 4.7 |

| α7(−/−) | 34.3 ± 3.3 |

3.1.2. No change in baseline L-dopa-induced AIM scores in saccharin-treated α4(−/−) nAChR compared to wild type mice

Wild type and α4 knockout mice were subsequently treated with L-dopa, which resulted in the development of stable AIMs after 2 wk [34, 35]. Our previous data had shown that total L-dopa-induced AIMs were variable in mice and that the scores tended to fall into two categories, moderate (< 35) and high AIM scores (> 35) [34, 35]. Our earlier results also showed that the effects of genetic deletions and drugs may vary with AIM severity [34, 35, 43]. The mice in the current study were therefore divided into 2 groups, those with moderate and those with high AIMs, and the data presented in this fashion in all figures and tables. The results in Table 2 show that there were no differences in L-dopa-induced AIM scores in saccharin-treated wild type compared to saccharin-treated α4 nAChR knockout mice in either the moderate or high AIMs group. Thus, the α4 genotype did not affect baseline L-dopa-induced AIM levels.

Table 2.

No change in baseline L-dopa-induced AIM scores in saccharin-treated α4(−/−) nAChR compared to wild type mice. α4 nAChR null mutant mice and their wild type littermates were lesioned with 6-OHDA. Three wk later they were injected once daily with L-dopa (3 mg/kg) plus benserazide (15 mg/kg), as depicted in the timeline in Fig. 1. The data were obtained in wk 10, 15 and 25 of the saccharin/nicotine treatment phase. Mice were evaluated for oral, axial, forelimb and total AIMs for 1 min every 15 min over a 2-h period. Data shown are for the saccharin-treated mice only. Values represent the mean ± SEM of 4–6 mice.

| Group | AIM type | Genotype | AIM score |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wk 10 | Wk 15 | Wk 25 | |||

| Moderate | Total | α4 (+/+) | 30.2 ± 3.2 | 31.0 ± 3.9 | 27.3 ± 1.8 |

| AIM scores | α4(−/−) | 30.3 ± 2.1 | 32.0 ± 5.0 | 27.7 ± 2.8 | |

| Oral | α4 (+/+) | 10.5 ±0.5 | 12.3 ±0.3 | 10.8 ± 1.3 | |

| α4(−/−) | 10.7 ± 1.1 | 11.8 ± 1.1 | 11.0 ± 0.6 | ||

| Axial | α4 (+/+) | 6.0 ± 2.0 | 5.8 ± 3.3 | 4.0 ± 1.8 | |

| α4(−/−) | 7.2 ± 1.2 | 6.0 ± 2.2 | 5.5 ± 1.9 | ||

| Forelimb | α4 (+/+) | 13.8 ± 2.1 | 13.0 ± 1.1 | 12.5 ± 1.3 | |

| α4(−/−) | 12.5 ± 1.2 | 14.2 ± 2.0 | 11.2 ± 0.9 | ||

| High | Total | α4 (+/+) | 68.5 ± 17.3 | 63.5 ± 13.6 | 51.0 ± 9.6 |

| AIM scores | α4(−/−) | 64.0 ± 7.0 | 49.2 ± 7.2 | 46.0 ± 5.1 | |

| Oral | α4 (+/+) | 20.0 ±3.2 | 16.8 ± 3.3 | 11.8 ± 0.3 | |

| α4(−/−) | 16.8 ± 1.5 | 14.8 ± 1.7 | 12.0 ± 0.5 | ||

| Axial | α4 (+/+) | 22.8 ± 8.9 | 24.3 ± 6.0 | 20.8 ± 4.5 | |

| α4(−/−) | 22.8 Ch 3.5 | 17.2 ± 3.3 | 18.0 ± 3.0 | ||

| Forelimb | α4 (+/+) | 25.8 ± 7.0 | 22.5 ± 5.8 | 18.5 ± 5.0 | |

| α4(−/−) | 24.4 ±2.9 | 17.2 ± 2.9 | 16.0 ± 2.4 | ||

3.1.3. Nicotine treatment reduces L-dopa-induced AIMs in wild type but not α4(−/−) nAChR mice

The effect of nicotine treatment was next assessed on L-dopa-induced AIM scores in α4 wild type and knockout mice, with the data for the mice with high AIM scores shown in Fig. 2. There was a decrease in AIM scores in the nicotine-treated α4 wild type mice, with a significant main effect for total AIMs (F(1,42) = 6.53, p < 0.05), oral AIMs (F(1,42) = 5.99, p < 0.05) and forelimb AIMs (F(1,42) = 5.67, p < 0.05) by two-way ANOVA. However, there were no significant main effects of treatment in the α4 nAChR knockout mice. Similar results were obtained in mice with moderate AIM scores, that is, nicotine treatment reduced L-dopa-induced AIMs in the wild type but not α4 nAChR subunit null mutant mice. In the moderately dyskinetic α4 wild type mice, there was a significant main effect of nicotine treatment on total AIMs (F(1,96) = 6.83, p < 0.05), oral AIMs (F(1,96) = 8.21, p < 0.01) and forelimb AIMs (F(1,96) = 8.02, p < 0.01) by two-way ANOVA. By contrast, there was only a significant main effect of nicotine treatment on oral AIMs in the α4 knockout mice ((F(1,60) = 5.85, p < 0.05). These data, combined with our previous investigations [34, 35] support a role for α4β2* nAChRs in the nicotine-mediated reduction in L-dopa-induced AIMs.

Fig. 2.

Nicotine treatment reduces L-dopa-induced AIMs in wild type but not α4(−/−) nAChR mice. Lesioned mice were injected once daily with L-dopa (3 mg/kg) plus benserazide (15 mg/kg) and provided with nicotine in the drinking water. Mice were evaluated for oral, axial, forelimb and total AIMs for 1 min every 15 min over a 2-h period. The times on the x-axis correspond to the wk on nicotine treatment (white boxes in Fig. 1). Values represent the mean ± SEM of 4–5 animals. Where the SEM is not shown, it fell within the symbol. # indicates a significant (p < 0.05) main effect of nicotine using two-way ANOVA.

3.1.4. Plasma cotinine levels in α4(−/−) nAChR and wild type mice

Plasma cotinine levels were measured as an index of nicotine consumption. Cotinine, a primary nicotine metabolite, provides a relatively good index of nicotine intake because of its long half-life (18 h) [37, 44]. Plasma cotinine levels were similar in nicotine-treated wild type and α4 knockout mice 3 months after the start of nicotine treatment (Table 3) and remained at comparable levels throughout the study.

Table 3.

Plasma cotinine levels in lesioned wild type and knockout mice treated with nicotine. Unilateral 6-OHDA-lesioned L-dopa-treated wild type and null mutant mice were given saccharin without and with nicotine (300 µg/ml) in the drinking water. Plasma cotinine levels shown were measured 2 to 3 months after the start of nicotine treatment, and are representative of the levels throughout the study. Cotinine levels were not detected in saccharin-treated mice. Values represent the mean ± SEM of 10–17 mice.

| nAChR subunit deletion | Group | Cotinine level (ng/ml) |

|---|---|---|

| α4 | Wild type Null mutant |

384 ± 110 350 ± 71 |

| α7 | Wild type Null mutant |

280 ± 71 301 ± 77 |

3.2. Studies with α7 nAChR(−/−) and wildtype mice

3.2.1. No change in parkinsonism in α7 nACh (−/−) mice compared to wild type

α7 nAChR knockout and wild type mice were lesioned and treated with nicotine and L-dopa as depicted in the timeline to Fig. 3. Experiments were performed to test whether the absence of α7* nAChRs affected parkinsonism after a unilateral 6-OHDA lesion. No differences were observed in the forelimb asymmetry test between wild type and α7 knockout mice (Table 1).

Fig. 3.

Treatment timeline for α7 nAChR null mutant and wild type mice. All mice were unilaterally lesioned with 6-OHDA. Parkinsonism was evaluated 2 wk later using the forelimb asymmetry test. Daily L-dopa (3 mg/kg) plus benserazide (15 mg/kg) dosing was initiated 3 wk after lesioning and continued throughout the study. After L-dopa-induced AIMs had stably developed, nicotine was given in the drinking water, as indicated in the timeline. The numbers in the white squares represent the wk on nicotine treatment. L-dopa-induced AIMs were measured throughout the study.

3.2.2. Increase in baseline L-dopa-induced AIMs in saccharin-treated α7(−/−) nAChR compared to wild type mice

Wild type and α7 nAChR knockout mice were lesioned and treated with L-dopa as depicted in the timeline in Fig. 3. As described earlier for the α4(−/−) nAChR studies, the mice were divided into two subgroups, those with moderate and those with high AIM scores. The results in Fig. 4 show that there was increased expression of L-dopa-induced AIMs in the saccharin-treated α7 knockout mice compared to the wild type littermates in both the moderate and high AIMs group. In the moderate AIMs group, there was a significant main effect of genotype on total (F(1,88) = 15.52, p < 0.001), oral (F(1,88) = 18.91, p < 0.001) and forelimb (F(1,88) = 11.43, p < 0.01) AIMs. In the high AIMs group, there was also a significant main effect of genotype for total (F(1,165) = 16.90, p < 0.001), oral (F(1,165) = 11.63, p < 0.001), axial (F(1,165) = 10.88, p < 0.01) and forelimb (F(1,165) = 16.66, p < 0.001) AIMs. In the mice with moderate AIMs, the enhanced AIM levels in the α7 knockout mice were more pronounced with the first wk of saccharin treatment and declined towards the end of the study period (23 wk). In the high AIMs group, the scores were generally elevated for the entire treatment period.

Fig. 4.

Increase in L-dopa-induced AIMs in saccharin-treated α7(−/−) nAChR compared to wild type mice. 6-OHDA-lesioned mice were injected once daily with L-dopa (3 mg/kg) plus benserazide (15 mg/kg). They were evaluated for oral, axial, forelimb and total AIMs for 1 min every 15 min over a 2-h period. The mice were subdivided into two groups, those with moderate and those with high AIM scores. The times on the x-axis correspond to the wk on nicotine treatment (white boxes in Fig. 3). Values represent the mean ± SEM of 4–6 mice in the moderate AIMs group and 8–9 mice in the high AIMs group. Where the SEM is not shown, it fell within the symbol. There was a significant main effect of genotype using two-way ANOVA (## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001). Significance of difference between saccharin-treated wild type and saccharin-treated α7(−/−), *p < 0.05 using a two-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni post hoc test.

3.2.3. Nicotine treatment reduces L-dopa-induced AIMs in both wild type and α7(−/−) nAChR mice

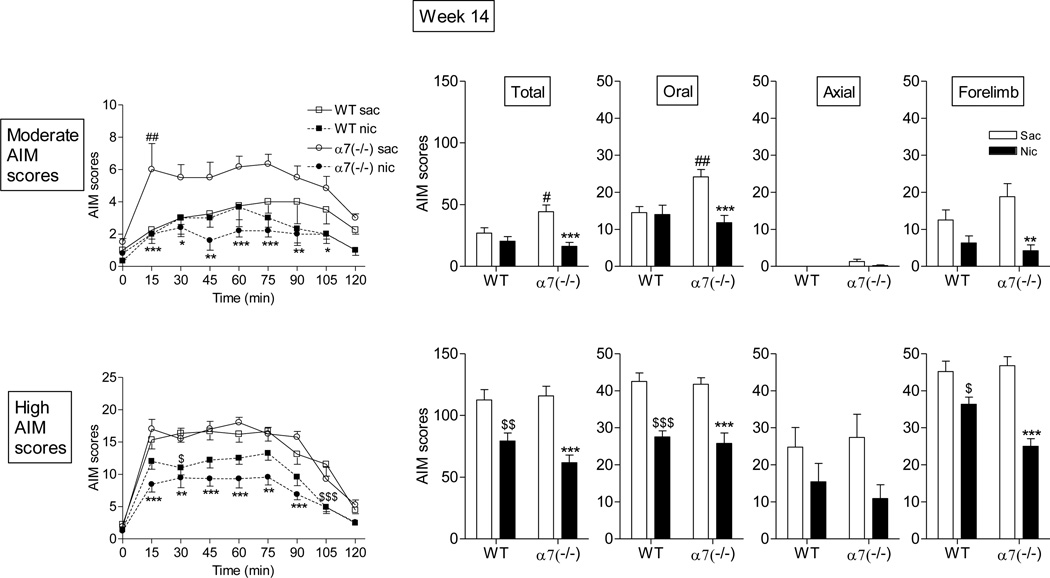

We next tested the effect of nicotine treatment in α7 wild type and knockout mice. After 5 wk of treatment, there was no effect of nicotine on L-dopa-induced AIMs in wild type mice (Fig. 5). These data are consistent with our previous studies which show that several months of treatment is required to reduce AIMs in L-dopa-primed mice [34]. However, after 5 wk, nicotine did reduce AIMs in α7 nAChR knockout mice, which had elevated AIM levels. Similar results were observed at this time point with mice that exhibited either moderate or high AIMs. After 14 wk of treatment, nicotine reduced L-dopa-induced AIMs in both the moderate and high AIM scoring groups of the α7(−/−) but only in the high AIMs group of the wild type mice (Fig. 6). By 23 wk of treatment, nicotine reduced L-dopa-induced AIMs to a similar extent in α7(−/−) mice and wild type mice (Fig. 7).

Fig. 5.

Nicotine reduces L-dopa-induced AIMs in α7(−/−) mice but not wild type mice after 5 wk of treatment. Lesioned mice were injected with L-dopa (3 mg/kg) plus benserazide (15 mg/kg) and given nicotine (nic) in the saccharin (sac)-containing drinking water for 5 wk. The daily time course of the nicotine-mediated reduction in total AIMs is provided on the left. The effect of nicotine on total, oral, axial and forelimb AIMs is shown in the panels on the right. The mice were subdivided into two groups, those with moderate and those with high AIM scores. Values represent the mean ± SEM of 3–6 in the moderate AIMs group and 8–10 in the high AIMs group. Where the SEM is not shown, it fell within the symbol. Significance of difference between the α7(−/−) saccharin-treated and the α7(−/−) nicotine-treated mice, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01; significance of difference between saccharin-treated wild type and saccharin-treated α7(−/−) mice, #p < 0.05, ###p < 0.001 using two-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni post hoc test.

Fig. 6.

Nicotine more prominently reduces L-dopa-induced AIMs in α7(−/−) mice than wild type mice after 14 wk of treatment. Mice were treated as described in the legend to Fig. 5. The daily time course of the nicotine-mediated reduction in total AIMs is provided on the left. The effect of nicotine on total, oral, axial and forelimb AIMs is shown in the panels on the right. The mice were subdivided into two groups, those with moderate and those with high AIM scores. Values represent the mean ± SEM of 3–6 in the moderate AIMs group and 8–10 in the high AIMs group. Significance of difference between saccharin (sac)-treated wild type and nicotine (nic)-treated wild type mice, $p < 0.05, $$p < 0.01, $$$p < 0.001; significance of difference between saccharin-treated α7(−/−) and nicotine-treated α7(−/−) mice, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; significance of difference between saccharin-treated wild type and saccharin-treated α7(−/−), #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 using two-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni post hoc test.

Fig. 7.

Nicotine reduces L-dopa-induced AIMs to a similar extent in α7(−/−) mice and wild type mice after 23 wk of treatment. Mice were treated as described in the legend to Fig. 5. The daily time course of the nicotine-mediated reduction in total AIMs is provided on the left. The effect of nicotine on total, oral, axial and forelimb AIMs is shown in the panels on the right. The mice were subdivided into two groups, those with moderate and those with high AIM scores. Values represent the mean ± SEM of 3–6 in the moderate AIMs group and 8–10 in the high AIMs group. Where the SEM is not shown, it fell within the symbol. Significance of difference between saccharin (sac)-treated wild type and nicotine (nic)-treated wild type mice, $p < 0.05, $$p < 0.01, $$$p < 0.001; significance of difference between saccharin-treated α7(−/−) and nicotine-treated α7(−/−) mice, *p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01, ***, p < 0.001 using two-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni post hoc test.

3.2.4. Plasma cotinine levels in α7 nAChR(−/−) and wild type mice

Plasma cotinine levels were measured to ensure that the mice were receiving adequate levels of nicotine in the drinking water. Plasma cotinine levels were comparable in nicotine-treated wild type and α7 knockout mice 2 months after the start of nicotine treatment (Table 3), with similar plasma levels throughout the study.

4. Discussion

The use of nAChR null mutant mice has proved a valuable resource for identifying the role of nAChRs in CNS functions linked to the dopaminergic system, including addiction and locomotor activity [45–48]. Here, we used α4 and α7 nAChR subunit knockout mice to understand if these subtypes are involved in L-dopa-induced AIMs. The results show that the α4* nAChR appears to play an important role since nicotine generally failed to decrease L-dopa-induced AIMs in α4(−/−) nAChR subunit mice. Nicotine treatment did reduce AIMs in α7 nAChR knockout mice; however, such mice exhibited higher L-dopa-induced AIM levels suggesting that α7 nAChRs exert an inhibitory influence. Thus both α4* and α7 nAChRs appear to regulate L-dopa-induced AIMs, possibly in an opposing fashion.

Previous findings had also indicated that α6β2* nAChRs are involved in the nicotine-mediated decline in L-dopa-induced AIMs. Both β2 and α6 nAChR subunit deletion decreased baseline AIMs, as well as the ability of nicotine to further reduce L-dopa-induced AIMs [34, 35] (summarized in Table 4). Thus both α4β2* and α6β2* nAChR subtypes appear involved in the nicotine-mediated decrease in L-dopa-induced AIMs, although in a somewhat different manner. One possibility is that the α6α4β2β3 nAChR subtype is critical for the effect of nicotine on AIMs. Our rationale for this suggestions is based on findings showing that nicotine does not decrease AIMs in α6 null mutants that lack the α6α4β2β3 and α6β2 subtypes, but still express α4β2 and α4α5β2 nAChR [34, 35]. Moreover, nicotine did not reduce AIMs in α4 null mutants that lack α6α4β2β3, α4β2 and α4α5β2 nAChRs. The population common to both studies is the α6α4β2β3 receptor. The idea that this latter subtype is important is consistent with reports showing that α6α4β2β3 nAChRs mediate nicotine’s effects on dopamine neuron firing and endogenous dopamine release [49–51].

Table 4.

Several nAChR subtypes play a role in L-dopa-induced Aims

The suggestion that compounds interacting with β2* nAChRs may reduce L-dopa-induced dyskinesias agrees with previous studies using nAChR drugs. A-85380 and a series of Targacept compounds that selectively act at β2* nAChRs all reduced AIMs in 6-OHDA-lesioned rats [31, 52]. There are currently no α4β2* nor α6β2* selective nAChR compounds available to evaluate the separate role of these subtypes in behavior [30, 52, 53]. To date, the effect of drugs targeting α7 nAChRs has not yet been examined.

Our data show that deletion of α7 nAChRs also affects L-dopa-induced AIMs, albeit in a manner distinct from that of α4* or α6* nAChRs. An increase in baseline L-dopa-induced AIMs was observed in α7 null mutant mice, suggesting that this subtype has an inhibitory impact on the development of AIMs. However, nicotine still reduced L-dopa-induced AIMs in α7 knockout mice. This improvement in AIMs in the α7 nAChR knockout mice is probably mediated via α4β2* and/or α6β2* nAChRs, which are unaffected by deletion of the α7 nAChR transcript [54].

A point of note is that the regulation of L-dopa-induced AIMs by β2* nAChRs appears quite distinct from that by α7 nAChRs. Although the α6 deletion reduced baseline L-dopa-induced AIM scores, both α6 and α4 nAChR subunit deletion led to a loss of the nicotine-mediated antidyskinetic effect (Table 4). By contrast, α7 nAChR subunit deletion resulted in an increase in baseline L-dopa-induced AIMs activity, but did not affect the antidyskinetic effect of nicotine. These differences may relate to the fact that α7 and the two β2* nAChR subtypes are functionally quite distinct. For instance, α7 nAChRs are much more permeable to calcium, desensitize more rapidly and are linked to different intracellular cell signaling steps compared to β2* nAChRs [55–59]. These unique molecular properties may provide a basis for the varying effects of α7 and β2* nAChR-directed drugs on behaviors, such as L-dopa-induced dyskinesias.

Although α6β2*, α4β2* and α7 nAChRs are all present in the striatum, it is not known whether alterations in baseline L-dopa-induced AIMs and/or the lack of effectiveness of nicotine in the α4, α6 or α7 nAChR null mutant mice are due to deletion of receptors in the striatum or in other brain areas. For instance, α4β2* and α7 nAChRs are widely distributed throughout the CNS. This includes numerous other areas linked to motor control and coordination, such as the thalamus, cortex and cerebellum. Any one, or a combination, of these regions may play a role in the occurrence of L-dopa-induced AIMs. The α6β2* nAChRs are somewhat more selectively localized to catecholaminergic regions in the brain. However, although they are most prominently present in the striatum, α6β2* nAChRs are also present in the substantia nigra, the locus coeruleus and its projection areas, as well as multiple components of the visual system [60–62]. Selective localized ablation of nAChRs is necessary to identify the populations involved in the generation of L-dopa-induced AIMs.

In conclusion, the present results using nAChR knockout mice suggest that α6β2*, α4β2* and α7 nAChRs all influence the expression of L-dopa-induced AIMs in varying ways. Thus, select nAChR drugs interacting at one or more nAChR subtypes may prove most useful as antidyskinetic agents.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jason Ly for excellent technical assistance.

Glossary

- α-CtxMII

α-conotoxinMII

- nAChR

-

nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

*indicates the possible presence of other subunits in the receptor complex

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

This work was supported by NIH grants NS59910, NS65851, and DA015663.

Authorship contributions

Participated in research design: MQ, CC, SG; Conducted experiments: CC Provided experimental tools (null mutant and wild type mice): SG; Performed data analyses: MQ, CC; Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: MQ, CC, SG.

References

- 1.Poewe W, Mahlknecht P, Jankovic J. Emerging therapies for Parkinson's disease. Curr Opin Neurol. 2012;25:448–459. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e3283542fde. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brotchie J, Jenner P. New approaches to therapy. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2011;98:123–150. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381328-2.00005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carta M, Bezard E. Contribution of pre-synaptic mechanisms to l-DOPA-induced dyskinesia. Neuroscience. 2011;198:245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.07.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisone G, Bezard E. Molecular mechanisms of l-DOPA-induced dyskinesia. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2011;98:95–122. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381328-2.00004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iravani MM, Jenner P. Mechanisms underlying the onset and expression of levodopa-induced dyskinesia and their pharmacological manipulation. J Neural Transm. 2011;118:1661–1690. doi: 10.1007/s00702-011-0698-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cenci MA, Konradi C. Maladaptive striatal plasticity in l-DOPA-induced dyskinesia. Progress in brain research. 2010;183C:209–233. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(10)83011-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prashanth LK, Fox S, Meissner WG. l-Dopa-induced dyskinesia-clinical presentation, genetics, and treatment. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2011;98:31–54. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381328-2.00002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rascol O, Lozano A, Stern M, Poewe W. Milestones in Parkinson's disease therapeutics. Mov Disord. 2011;26:1072–1082. doi: 10.1002/mds.23714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gottwald MD, Aminoff MJ. Therapies for dopaminergic-induced dyskinesias in parkinson disease. Annals of neurology. 2011;69:919–927. doi: 10.1002/ana.22423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sawada H, Oeda T, Kuno S, Nomoto M, Yamamoto K, Yamamoto M, et al. Amantadine for dyskinesias in Parkinson's disease: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huot P, Johnston TH, Koprich JB, Fox SH, Brotchie JM. The pharmacology of L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia in Parkinson's disease. Pharmacol Rev. 2013;65:171–222. doi: 10.1124/pr.111.005678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hinson VK. Parkinson's disease and motor fluctuations. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2010;12:186–199. doi: 10.1007/s11940-010-0067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sankar T, Lozano AM. Surgical approach to l-dopa-induced dyskinesias. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2011;98:151–171. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381328-2.00006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fasano A, Daniele A, Albanese A. Treatment of motor and non-motor features of Parkinson's disease with deep brain stimulation. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:429–442. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quik M, Wonnacott S. {alpha}6{beta}2* and {alpha}4{beta}2* Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors As Drug Targets for Parkinson's Disease. Pharmacol Rev. 2011;63:938–966. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grady SR, Salminen O, Laverty DC, Whiteaker P, McIntosh JM, Collins AC, et al. The subtypes of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on dopaminergic terminals of mouse striatum. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;74:1235–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Millar NS, Gotti C. Diversity of vertebrate nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56:237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luo R, Janssen MJ, Partridge JG, Vicini S. Direct and GABA-mediated indirect effects of nicotinic ACh receptor agonists on striatal neurones. J Physiol. 2013;591:203–217. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.241786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaiser S, Wonnacott S. alpha-bungarotoxin-sensitive nicotinic receptors indirectly modulate [(3)H]dopamine release in rat striatal slices via glutamate release. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58:312–318. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.2.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bordia T, Campos C, Huang L, Quik M. Continuous and intermittent nicotine treatment reduces L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA)-induced dyskinesias in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;327:239–247. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.140897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quik M, Cox H, Parameswaran N, O'Leary K, Langston JW, Di Monte D. Nicotine reduces levodopa-induced dyskinesias in lesioned monkeys. Annals of neurology. 2007;62:588–596. doi: 10.1002/ana.21203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bordia T, Campos C, McIntosh JM, Quik M. Nicotinic receptor-mediated reduction in L-dopa-induced dyskinesias may occur via desensitization. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;333:929–938. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.162396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quik M, Mallela A, Chin M, McIntosh JM, Perez XA, Bordia T. Nicotine-mediated improvement in l-dopa-induced dyskinesias in MPTP-lesioned monkeys is dependent on dopamine nerve terminal function. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;50:30–41. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coe JW, Brooks PR, Vetelino MG, Wirtz MC, Arnold EP, Huang J, et al. Varenicline: an alpha4beta2 nicotinic receptor partial agonist for smoking cessation. J Med Chem. 2005;48:3474–3477. doi: 10.1021/jm050069n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rollema H, Coe JW, Chambers LK, et al. Rationale, pharmacology and clinical efficacy of partial agonists of alpha(4)beta(2) nACh receptors for smoking cessation. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:316–325. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rollema H, Chambers LK, Coe JW, Glowa J, Hurst RS, Lebel LA, et al. Pharmacological profile of the alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist varenicline, an effective smoking cessation aid. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:985–994. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gonzales D, Rennard SI, Nides M, Oncken C, Azoulay S, Billing CB, et al. Varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs sustained-release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2006;296:47–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jorenby DE, Hays JT, Rigotti NA, Azoulay S, Watsky EJ, Williams KE, et al. Efficacy of varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs placebo or sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2006;296:56–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mihalak KB, Carroll FI, Luetje CW. Varenicline is a partial agonist at alpha4beta2 and a full agonist at alpha7 neuronal nicotinic receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:801–805. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.025130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bordia T, Hrachova M, Chin M, McIntosh JM, Quik M. Varenicline is a potent partial agonist at alpha6beta2* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in rat and monkey striatum. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;342:327–34. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.194852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang LZ, Campos C, Ly J, Carroll FI, Quik M. Nicotinic receptor agonists decrease L-dopa-induced dyskinesias most effectively in moderately lesioned parkinsonian rats. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60:861–868. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mukhin AG, Gundisch D, Horti AG, Koren AO, Tamagnan G, Kimes AS, et al. 5-Iodo-A-85380, an alpha4beta2 subtype-selective ligand for nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;57:642–649. doi: 10.1124/mol.57.3.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kulak JM, Sum J, Musachio JL, McIntosh JM, Quik M. 5-Iodo-A-85380 binds to alpha-conotoxin MII-sensitive nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) as well as alpha4beta2* subtypes. J Neurochem. 2002;81:403–406. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang L, Grady SR, Quik M. Nicotine Reduces L-Dopa-Induced Dyskinesias by Acting at {beta}2 Nicotinic Receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;338:932–941. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.182949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quik M, Park KM, Hrachova M, Mallela A, Huang LZ, McIntosh JM, et al. Role for alpha6 nicotinic receptors in l-dopa-induced dyskinesias in parkinsonian mice. Neuropharmacology. 2012;63:450–459. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salminen O, Murphy KL, McIntosh JM, Drago J, Marks MJ, Collins AC, et al. Subunit composition and pharmacology of two classes of striatal presynaptic nicotinic acetylcholine receptors mediating dopamine release in mice. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:1526–1535. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.6.1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lai A, Parameswaran N, Khwaja M, Whiteaker P, Lindstrom JM, Fan H, et al. Long-term nicotine treatment decreases striatal alpha6* nicotinic acetylcholine receptor sites and function in mice. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67:1639–1647. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.006429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pietila K, Ahtee L. Chronic Nicotine Administration in the Drinking Water Affects the Striatal Dopamine in Mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;66:95–103. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00235-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sparks JA, Pauly JR. Effects of continuous oral nicotine administration on brain nicotinic receptors and responsiveness to nicotine in C57Bl/6 mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;141:145–153. doi: 10.1007/s002130050818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cenci MA, Lundblad M. Ratings of L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia in the unilateral 6-OHDA lesion model of Parkinson's disease in rats and mice. Curr Protoc Neurosci. 2007:1–23. doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0925s41. Chapter 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schallert T, Fleming SM, Leasure JL, Tillerson JL, Bland ST. CNS plasticity and assessment of forelimb sensorimotor outcome in unilateral rat models of stroke, cortical ablation, parkinsonism and spinal cord injury. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:777–787. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brooks SP, Dunnett SB. Tests to assess motor phenotype in mice: a user's guide. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrn2652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carta M, Carlsson T, Kirik D, Bjorklund A. Dopamine released from 5-HT terminals is the cause of L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia in parkinsonian rats. Brain. 2007;130:1819–1833. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matta SG, Balfour DJ, Benowitz NL, Boyd RT, Buccafusco JJ, Caggiula AR, et al. Guidelines on nicotine dose selection for in vivo research. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;190:269–319. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0441-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fowler CD, Arends MA, Kenny PJ. Subtypes of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in nicotine reward, dependence, and withdrawal: evidence from genetically modified mice. Behav Pharmacol. 2008;19:461–84. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32830c360e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cordero-Erausquin M, Marubio LM, Klink R, Changeux JP. Nicotinic receptor function: new perspectives from knockout mice. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2000;21:211–217. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01489-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Champtiaux N, Changeux JP. Knockout and knockin mice to investigate the role of nicotinic receptors in the central nervous system. Prog Brain Res. 2004;145:235–251. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(03)45016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Changeux JP. Nicotine addiction and nicotinic receptors: lessons from genetically modified mice. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:389–401. doi: 10.1038/nrn2849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Exley R, Maubourguet N, David V, Eddine R, Evrard A, Pons S, et al. Distinct contributions of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit alpha4 and subunit alpha6 to the reinforcing effects of nicotine. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:7577–7582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103000108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu L, Zhao-Shea R, McIntosh JM, Gardner PD, Tapper AR. Nicotine persistently activates ventral tegmental area dopaminergic neurons via nicotinic acetylcholine receptors containing alpha4 and alpha6 subunits. Mol Pharmacol. 2012;81:541–548. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.076661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhao-Shea R, Liu L, Soll LG, Improgo MR, Meyers EE, McIntosh JM, et al. Nicotine-mediated activation of dopaminergic neurons in distinct regions of the ventral tegmental area. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:1021–1032. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Quik M, Campos C, Bordia T, Strachan JP, Zhang J, McIntosh JM, et al. alpha4beta2 nicotinic receptors play a role in the nAChR-mediated decline in l-dopa-induced dyskinesias in parkinsonian rats. Neuropharmacology. 2013;71:191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marks MJ, Wageman CR, Grady SR, Gopalakrishnan M, Briggs CA. Selectivity of ABT-089 for alpha4beta2* and alpha6beta2* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in brain. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;78:795–802. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seguela P, Wadiche J, Dineley-Miller K, Dani JA, Patrick JW. Molecular cloning, functional properties, and distribution of rat brain alpha 7: a nicotinic cation channel highly permeable to calcium. J Neurosci. 1993;13:596–604. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00596.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Giniatullin R, Nistri A, Yakel JL. Desensitization of nicotinic ACh receptors: shaping cholinergic signaling. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:371–378. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Picciotto MR, Addy NA, Mineur YS, Brunzell DH. It is not "either/or": Activation and desensitization of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors both contribute to behaviors related to nicotine addiction and mood. Prog Neurobiol. 2008;84:329–342. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wonnacott S, Sidhpura N, Balfour DJ. Nicotine: from molecular mechanisms to behaviour. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2005;5:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Changeux JP. Allosteric receptors: from electric organ to cognition. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology. 2010;50:1–38. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Quik M, Perez XA, Bordia T. Nicotine as a potential neuroprotective agent for Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2012;27:947–957. doi: 10.1002/mds.25028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Whiteaker P, McIntosh JM, Luo S, Collins AC, Marks MJ. 125I-alpha-conotoxin MII identifies a novel nicotinic acetylcholine receptor population in mouse brain. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;57:913–925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Quik M, Polonskaya Y, Kulak JM, McIntosh JM. Vulnerability of 125I-alpha-conotoxin MII binding sites to nigrostriatal damage in monkey. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5494–5500. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-05494.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Champtiaux N, Han ZY, Bessis A, Rossi FM, Zoli M, Marubio L, et al. Distribution and pharmacology of alpha 6-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors analyzed with mutant mice. J Neurosci. 2002;22:1208–1217. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-04-01208.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]