Abstract

Background

Asthma is one of the most common chronic diseases in women of reproductive age, occurring in up to 8% of pregnancies.

Objective

Assess the prevalence of asthma medication use during pregnancy in a large diverse cohort.

Methods

We identified women aged 15 to 45 years who delivered a live born infant between 2001 and 2007 across 11 U.S. health plans within the Medication Exposure in Pregnancy Risk Evaluation Program (MEPREP). Using health plans’ administrative and claims data, and birth certificate data, we identified deliveries for which women filled asthma medications from 90 days before pregnancy through delivery. Prevalence (%) was calculated for asthma diagnosis and medication dispensing.

Results

There were 586,276 infants from 575,632 eligible deliveries in the MEPREP cohort. Asthma prevalence among mothers was 6.7%, increasing from 5.5% in 2001 to 7.8% in 2007. A total of 9.7% (n=55,914) of women were dispensed asthma medications during pregnancy. The overall prevalence of maintenance-only medication, rescue-only medication, and combined maintenance and rescue medication was 0.6%, 6.7%, and 2.4% respectively. The prevalence of maintenance-only use doubled during the study period from 0.4% to 0.8%, while rescue-only use decreased from 7.4% to 5.8%.

Conclusions

In this large population-based pregnancy cohort, the prevalence of asthma diagnoses increased over time. The dispensing of maintenance-only medication increased over time, while rescue-only medication dispensing decreased over time.

Keywords: Asthma, Pregnancy, Medication, Prevalence

Introduction

Asthma is one of the most common chronic diseases in women of reproductive age, occurring in up to 8% of pregnancies (1). Since uncontrolled asthma can lead to neonatal and maternal complications (2), treatment of persistent asthma with daily controller therapy (maintenance medications) is recommended during pregnancy. The National Asthma Education and Prevention Program recommends that asthmatic pregnant women be treated with asthma medications, since the maternal and fetal outcomes are improved compared to women whose asthma symptoms and exacerbations remain untreated during pregnancy (3).

Published studies of pregnancy outcomes in women with asthma treated with a variety of medications have inconsistent findings. Previous studies found increased risks for birth defects and other adverse pregnancy outcomes including oral clefts, spontaneous abortion or stillbirth, preterm delivery, preeclampsia, low birth weight, neonatal hypoxia, and cesarean section (4-6). Previous studies are based on pregnancy registries, birth defects surveillance programs, observational cohort studies, and case-control studies. Many of these studies have common limitations such as non-representative populations, small sample sizes, particularly when examining birth defects, and poor exposure assessment, which is often based on mother recall (6). While it is important to examine trends in asthma medication use during pregnancy to gain a better understanding of current use patterns and areas for future medication safety research, it is equally important to examine this information using a large representative cohort.

The primary aim of the current study was to report the prevalence of asthma diagnosis and asthma medication use throughout pregnancy within a large representative cohort from 11 geographically diverse U.S. health plans participating in the Medication Exposure in Pregnancy Risk Evaluation Program (MEPREP). Findings from this study can identify areas for further research by highlighting the most commonly dispensed asthma medications and timing, and populations where dispensations are highest.

Methods

Data source

This study used data from MEPREP, a collaborative research program between the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Kaiser Permanente of California, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine/Tennessee State Medicaid, and 11 health plan-affiliated research institutions, including Group Health Research Institute (Washington), Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute (Massachusetts), HealthPartners Research Foundation (Minnesota), Kaiser Permanente Colorado, Kaiser Permanente Georgia, Kaiser Permanente Northwest (Oregon, Washington), Meyers Primary Care Institute (Massachusetts), and Lovelace Clinic Foundation (New Mexico)(7). Together, the health plans in MEPREP provide care to approximately 12 million current enrollees within 9 states, covering geographically and ethnically diverse populations receiving care within a wide array of medical care delivery models.

To support multi-site studies of medication safety in pregnancy, information on maternal and infant enrollment, demographics, outpatient pharmacy dispensings, and outpatient and inpatient health care encounters was extracted from the health plans’ administrative and claims databases. This information was linked to birth certificate data, including information on sociodemographic, medical, and reproductive factors. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of each participating organization and the State Departments of Public Health, where applicable.

Study population, asthma diagnosis, and exclusion based on selected underlying illness

The current study included pregnant mothers aged 15 to 45 years who delivered one or more live-born infants between January 1, 2001 and December 31, 2007. To be eligible for the study, mothers had to be continuously enrolled in the health plan with pharmacy benefits from 90 days before pregnancy through the date of delivery. Mothers were classified as asthmatic for a particular pregnancy if they had an asthma diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification: ICD9-CM 493) during the period 180 days before pregnancy through the date of delivery.

Some of the medications used for asthma are also used for other pulmonary conditions. Because we wanted to restrict our analyses to medications used by pregnant women with asthma, at the initial data extraction stage we excluded women who were diagnosed with any of the following underlying illnesses from 90 days prior to pregnancy through delivery: cystic fibrosis (ICD9-CM 277.xx), immunodeficiency (ICD9-CM 279.xx), bronchiectasis (ICD9-CM 494.x), hereditary and degenerative diseases of the central nervous system (ICD9-CM 330-337.xx), psychoses (ICD9-CM 290-301.xx), mental retardation (ICD9-CM 317.x, 318.x, 319.x), heart failure (ICD9-CM 428-429.9), chronic bronchitis, emphysema (ICD9-CM 491.xx - 492.8), pulmonary hypertension and/or embolism (ICD9-CM 415.xx, 416.xx, 417.xx), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (ICD9-CM 496).

Asthma medications of interest

We identified deliveries for which the women filled asthma medications any time from 90 days before pregnancy through the date of delivery. Appendix A lists the asthma medications of interest. The list of medications was classified into usage categories of ‘Maintenance’ and ‘Rescue’ medications. Maintenance medications included long acting beta-agonists (LABA), inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), leukotriene receptor antagonists (LRA), mast cell stabilizers, methlyxanthines, and combinations of ICS and LABA (ICS/LABA). Rescue medications included short acting beta-agonists (SABA), anticholinergics, and combinations of ipratropium and albuterol.

Definition of pregnancy dates

We developed a multi-stage algorithm to identify the start and end of pregnancy (including trimesters). For deliveries with data on the last menstrual period (LMP), we used the first day of the LMP as the first day of the first trimester (“day zero”). If the LMP was missing or had an improbable value, the start of pregnancy was defined as the date of delivery minus the gestational age based on clinical or obstetric estimates. This method is consistent with the approach used by the National Center for Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.(8) The birth certificate LMP has been validated previously by one of the participating health plans, which found a concordance within two weeks between the birth certificate LMP and the hospital records in 94% of the records reviewed (9).

For deliveries with missing gestational age information on the birth certificates, we estimated the trimesters using the delivery date and specific ICD-9-CM codes recorded in the health plan claims data. The algorithm assumed day zero as the date of delivery minus 270 days if there was no ICD-9-CM code for preterm birth; as the date of delivery minus 245 days if there was a code for preterm birth of unspecified gestational age; and as the date of delivery minus the upper limit of the gestational age range if there was a code for preterm birth with a specified range, e.g., the date of delivery minus 224 days for deliveries with an ICD-9-CM code 765.26 (“31 to 32 weeks of gestation”). A previous study that used the birth registry data at one of the participating health plans found that the mean gestational age according to the registry was 273 days, whereas the median gestational age was 275 days (10). The 270-day algorithm has been found to be valid for full term deliveries (11).

Identification of maternal demographic and clinical characteristics

We obtained information on maternal age at delivery and calendar year of delivery from the health plan administrative data. Information on maternal race/ethnicity, educational level, marital status, smoking, and mode of delivery was extracted from the birth certificate data. There was a large percentage of ‘unknown/missing’ data for marital status and smoking status; despite this limitation, the results for the data available within these two characteristics are presented.

Statistical analysis

The prevalence was calculated as a percentage and was calculated for asthma diagnosis and asthma medication use among the entire cohort and for subgroups by age, race, calendar year and other characteristics. For subgroups, the denominator was the total number of deliveries within each stratum of the examined characteristics. These results are presented on the overall cohort, as well as stratified by women with and without an asthma diagnosis. This allows for interpretation among two potentially different groups of women. The prevalence of use for each medication class was calculated among deliveries with at least one medication dispensing. Although we performed the chi square test of independence within each category all results were highly significant due to the large sample size and we therefore did not present these results. We chose not to perform any additional statistical tests because the main purpose was to generate hypotheses rather than test hypotheses, and due to a large sample size most differences are statistically different and therefore it is more important to interpret any differences from a clinical viewpoint.

Results

Study cohort

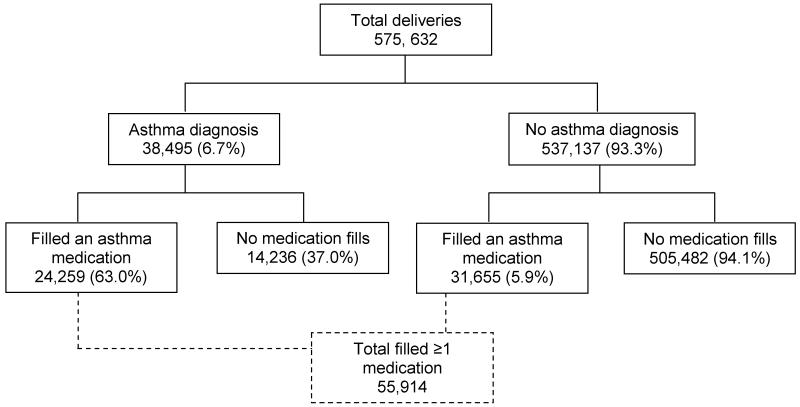

The total MEPREP population was 1,199,369 deliveries between 2001 and 2007. As shown in Figure 1, there were a total of 586,276 infants from 575,632 deliveries that met the study inclusion criteria. Of the 575,632 deliveries, 38,495 (6.7%) had an asthma diagnosis and of these 24,259 (63.0%) filled an asthma medication during the period from 90 days before pregnancy through the date of delivery. Of the 537,137 deliveries that did not have an asthma diagnosis, 31,655 (5.9%) filled an asthma medication. Table 1 presents characteristics of the total pregnancy-birth cohort stratified by asthma diagnosis status. At the time of delivery, 53.0% of the deliveries were by mothers aged between 25 and 34 years old, and 25.7% were between 18 and 24 years old; 44.2% were white, 23.0% were Hispanic, 15.5% were black, and 10.1% were Asian.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the maternal pregnancy cohort used in this study.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the pregnancy cohort (delivered an infant between 2001 and 2007) and asthma prevalence.

| Characteristics | Total | Asthma Prevalence | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| n | Column % | n | Row % (95% CI) | |

|

|

|

|||

| Deliveries (total) | 575,632 | 100 | 38,495 | 6.7 (6.6 - 6.8) |

|

|

|

|||

| Mother’s age at delivery | ||||

| <18 | 18,705 | 3.2 | 1,714 | 9.2 (8.7 -9.6) |

| 18-24 | 147,934 | 25.7 | 11,526 | 7.8 (7.7 - 7.9) |

| 25-34 | 305,211 | 53.0 | 18,780 | 6.2 (6.1 -6.2) |

| 35-45 | 103,782 | 18.0 | 6,475 | 6.2 (6.1 -6.4) |

|

|

|

|||

| Mother’s marital status | ||||

| Married | 157,103 | 27.3 | 9,097 | 5.8 (5.7 - 5.9) |

| Not Married | 103,558 | 18.0 | 7,461 | 7.2 (7.0 - 7.4) |

| Unknown | 314,971 | 54.7 | 21,937 | 7.0 (6.9 -7.1) |

|

|

|

|||

| Mother’s education (yrs) | ||||

| <=12 | 242,486 | 42.1 | 16,908 | 7.0 (6.9 -7.1) |

| >12 | 306,114 | 53.2 | 19,934 | 6.5 (6.4 - 6.6) |

| Unknown | 27,032 | 4.7 | 1,653 | 6.1 (5.8 -6.4) |

|

|

|

|||

| Mother’s race | ||||

| White | 254,654 | 44.2 | 18,226 | 7.2 (7.1 -7.3) |

| Black | 89,385 | 15.5 | 6,595 | 7.4 (7.2 - 7.5) |

| Asian | 57,940 | 10.1 | 2,450 | 4.2 (4.1 -4.4) |

| Hispanic | 132,160 | 23.0 | 8,015 | 6.1 (5.9 - 6.2) |

| Native American | 1,411 | 0.2 | 146 | 10.3 (8.8 -11.9) |

| Other/unknown | 40,082 | 7.0 | 3,063 | 7.6 (7.4 - 7.9) |

|

|

|

|||

| Mother’s smoking status | ||||

| No | 246,175 | 42.8 | 15,646 | 6.4 (6.3 -6.5) |

| Yes | 38,895 | 6.8 | 3,485 | 9.0 (8.7 - 9.2) |

| Unknown | 290,562 | 50.5 | 19,364 | 6.7 (6.6 -6.8) |

|

|

|

|||

| Year of delivery | ||||

| 2001 | 81,449 | 14.1 | 4,487 | 5.5 (5.4 - 5.7) |

| 2002 | 82,433 | 14.3 | 4,746 | 5.8 (5.6 - 5.9) |

| 2003 | 82,560 | 14.3 | 5,189 | 6.3 (6.1 - 6.5) |

| 2004 | 80,784 | 14.0 | 5,433 | 6.7 (6.6 -6.9) |

| 2005 | 81,199 | 14.1 | 5,737 | 7.1 (6.9 - 7.2) |

| 2006 | 83,653 | 14.5 | 6,369 | 7.6 (7.4 - 7.8) |

| 2007 | 83,554 | 14.5 | 6,534 | 7.8 (7.6 - 8.0) |

Asthma prevalence = asthma diagnosis/Total

Prevalence of asthma diagnosis

A total of 6.7% of mothers (n=38,495) had at least one asthma diagnosis identified within the data during the period extending six months prior to pregnancy through the time of delivery (Figure 1 and Table 1). Asthma was more prevalent among younger (<18 and 18-24 years of age, 9.2% and 7.8% respectively), less educated (7.0%), Native American (10.3%), and smoking mothers (9.0% compared to non-smokers). The prevalence of asthma diagnosis increased over time from 5.5% in 2001 to 7.8% in 2007.

Prevalence of asthma medications

As shown in Table 2, 9.7% (n=55,914) of all deliveries were dispensed any asthma medication during pregnancy. Of all deliveries, 63.0% of those mothers with an asthma diagnosis (n=24,259) and 5.8% of those without an asthma diagnosis (n=31,655) received at least one dispensing of asthma medication. From 2001 to 2007, the prevalence of any asthma medication dispensing decreased by 14% (67.8% to 58.3%) among mothers with an asthma diagnosis and by 24% (6.5% to 4.9%) among mothers without an asthma diagnosis. Asthma medication dispensing was highest for younger (12.1%), unmarried (12.0%), less educated (10.5%), and Native American mothers (13.5%). However, these patterns differed when stratified by asthma diagnosis status (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence (%) of “any” asthma medication dispensing: among the entire cohort and stratified by asthma diagnosis (n = denominator; % = those with at least one medication filling).

| Total population |

Asthma diagnosis |

No asthma diagnosis |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

|

|

|

|

||||

| Total deliveries | 575,632 | 9.7 | 38,495 | 63.0 | 537,137 | 5.8 |

|

|

|

|

||||

| Mother’s age at delivery | ||||||

| <18 | 18,705 | 12.1 | 1,714 | 61.4 | 16,991 | 7.1 |

| 18-24 | 147,934 | 11.2 | 11,526 | 59.5 | 136,408 | 7.1 |

| 25-34 | 305,211 | 8.9 | 18,780 | 63.5 | 286,431 | 5.4 |

| 35-45 | 103,782 | 9.4 | 6,475 | 68.4 | 97,307 | 5.5 |

|

|

|

|

||||

| Mother’s marital status | ||||||

| Married | 157,103 | 10.5 | 9,097 | 66.9 | 148,006 | 7.0 |

| Not Married | 103,558 | 12.0 | 7,461 | 61.5 | 96,097 | 8.2 |

| Unknown | 314,971 | 8.6 | 21,937 | 61.9 | 293,034 | 4.6 |

|

|

|

|

||||

| Mother’s education (yrs) | ||||||

| <=12 | 242,486 | 10.5 | 16,908 | 61.9 | 225,578 | 6.6 |

| >12 | 306,114 | 9.2 | 19,934 | 63.6 | 286,180 | 5.4 |

| Unknown | 27,032 | 8.6 | 1,653 | 66.8 | 25,379 | 4.8 |

|

|

|

|

||||

| Mother’s race | ||||||

| White | 254,654 | 11.7 | 18,226 | 64.7 | 236,428 | 7.6 |

| Black | 89,385 | 9.5 | 6,595 | 58.7 | 82,790 | 5.6 |

| Asian | 57,940 | 6.3 | 2,450 | 64.1 | 55,490 | 3.8 |

| Hispanic | 132,160 | 7.7 | 8,015 | 62.8 | 124,145 | 4.1 |

| Native American | 1,411 | 13.5 | 146 | 60.3 | 1,265 | 8.1 |

| Other/unknown | 40,082 | 9.0 | 3,063 | 62.2 | 37,019 | 4.6 |

|

|

|

|

||||

| Mother’s smoking status | ||||||

| No | 246,175 | 9.5 | 15,646 | 64.8 | 230,529 | 5.7 |

| Yes | 38,895 | 16.9 | 3,485 | 63.4 | 35,410 | 12.3 |

| Unknown | 290,562 | 8.9 | 19,364 | 61.5 | 271,198 | 5.2 |

|

|

|

|

||||

| Year of delivery | ||||||

| 2001 | 81,449 | 9.8 | 4,487 | 67.8 | 76,962 | 6.5 |

| 2002 | 82,433 | 9.7 | 4,746 | 65.3 | 77,687 | 6.3 |

| 2003 | 82,560 | 9.9 | 5,189 | 66.0 | 77,371 | 6.2 |

| 2004 | 80,784 | 10.0 | 5,433 | 64.3 | 75,351 | 6.1 |

| 2005 | 81,199 | 9.8 | 5,737 | 61.8 | 75,462 | 5.9 |

| 2006 | 83,653 | 9.7 | 6,369 | 60.5 | 77,284 | 5.5 |

| 2007 | 83,554 | 9.1 | 6,534 | 58.3 | 77,020 | 4.9 |

Prevalence is calculated tor each stratum within each category.

Table 3 shows the prevalence of maintenance-only, rescue-only, and the combinations of maintenance and rescue medication dispensing. The prevalence of maintenance-only medication dispensing for the entire cohort was 0.6% (n=3,650) and was 4.7% among mothers with an asthma diagnosis and 0.3% among mothers without an asthma diagnosis. Maintenance-only medication use varied by maternal age and race. The prevalence of maintenance-only medication dispensing doubled over time from 0.4% in 2001 to 0.8% in 2007 among the entire cohort and this two-fold increase was more evident among those without an asthma diagnosis than those with a diagnosis. The prevalence of rescue-only medication dispensing for the entire cohort was 6.7% (n=38,383) and was 29.3% among mothers with an asthma diagnosis and 5.0% among mothers without an asthma diagnosis. This prevalence was highest for deliveries by younger mothers regardless of asthma diagnosis status. Unlike the findings for maintenance-only medication dispensing, the prevalence of rescue-only medication dispensing decreased over time from 7.4% in 2001 to 5.8% in 2007. The prevalence of combinations of maintenance and rescue medication dispensing for the entire cohort was 2.4% (n=13,881), and was 29.0% among mothers with an asthma diagnosis and 0.5% among mothers without an asthma diagnosis. Over time, the prevalence of dispensing of combinations of maintenance and rescue medications showed a very slight increase among the entire cohort (2.1% to 2.5% from 2001 to 2007), however, among mothers with an asthma diagnosis there was a decrease in dispensing over time (30.1% to 26.1% from 2001 to 2007).

Table 3.

Prevalence (%) of “maintenance-only”, “rescue-only”, and “both maintenance and rescue” asthma medication dispensing: among the entire cohort and stratified by asthma diagnosis (n = denominator; % = those with at least one medication filling).

| Total population |

Asthma diagnosis |

No asthma diagnosis |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maintenance | Rescue | Both | Maintenance | Rescue | Both | Maintenance | Rescue | Both | ||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| n | % | % | % | n | % | % | % | n | % | % | % | |

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Total | 575,632 | 0.6 | 6.7 | 2.4 | 38,495 | 4.7 | 29.3 | 29.0 | 537,137 | 0.3 | 5.0 | 0.51 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Mother’s age at

delivery |

||||||||||||

| <18 | 18,705 | 0.7 | 8.4 | 3.0 | 1,714 | 2.4 | 32.9 | 26.1 | 16,991 | 0.5 | 5.9 | 0.68 |

| 18-24 | 147,934 | 0.6 | 8.4 | 2.3 | 11,526 | 3.2 | 33.1 | 23.2 | 136,408 | 0.3 | 6.3 | 0.50 |

| 25-34 | 305,211 | 0.6 | 6.0 | 2.3 | 18,780 | 5.3 | 28.1 | 30.1 | 286,431 | 0.3 | 4.6 | 0.46 |

| 35-45 | 103,782 | 0.8 | 5.8 | 2.9 | 6,475 | 6.6 | 25.1 | 36.7 | 97,307 | 0.4 | 4.5 | 0.63 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Mother’s marital

status |

||||||||||||

| Married | 157,103 | 0.7 | 7.7 | 2.1 | 9,097 | 5.6 | 33.3 | 28.0 | 148,006 | 0.4 | 6.1 | 0.54 |

| Not Married | 103,558 | 0.7 | 9.1 | 2.2 | 7,461 | 2.8 | 35.3 | 23.4 | 96,097 | 0.5 | 7.1 | 0.61 |

| Unknown | 314,971 | 0.6 | 5.4 | 2.6 | 21,937 | 5.1 | 25.6 | 31.3 | 293,034 | 0.2 | 3.9 | 0.46 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Mother’s education

(yrs) |

||||||||||||

| <=12 | 242,486 | 0.6 | 7.6 | 2.3 | 16,908 | 3.4 | 31.7 | 26.8 | 225,578 | 0.4 | 5.8 | 0.51 |

| >12 | 306,114 | 0.7 | 6.1 | 2.5 | 19,934 | 5.8 | 27.2 | 30.7 | 286,180 | 0.3 | 4.6 | 0.51 |

| Unknown | 27,032 | 0.6 | 5.6 | 2.3 | 1,653 | 6.0 | 30.2 | 30.6 | 25,379 | 0.3 | 4.0 | 0.49 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Mother’s race | ||||||||||||

| White | 254,654 | 0.8 | 8.3 | 2.6 | 18,226 | 5.3 | 30.7 | 28.7 | 236,428 | 0.5 | 6.5 | 0.63 |

| Black | 89,385 | 0.4 | 6.7 | 2.3 | 6,595 | 2.8 | 30.2 | 25.7 | 82,790 | 0.2 | 4.9 | 0.43 |

| Asian | 57,940 | 0.5 | 4.1 | 1.7 | 2,450 | 5.8 | 25.3 | 33.0 | 55,490 | 0.3 | 3.2 | 0.35 |

| Hispanic | 132,160 | 0.4 | 5.0 | 2.2 | 8,015 | 4.4 | 28.0 | 30.4 | 124,145 | 0.2 | 3.5 | 0.38 |

| Native American | 1,411 | 0.4 | 9.6 | 3.5 | 146 | 2.7 | 30.8 | 26.7 | 1,265 | 0.2 | 7.2 | 0.79 |

| Other/unknown | 40,082 | 0.8 | 5.3 | 2.9 | 3,063 | 6.1 | 25.0 | 31.0 | 37,019 | 0.3 | 3.7 | 0.61 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Mother’s smoking

status |

||||||||||||

| No | 246,175 | 0.6 | 6.4 | 2.4 | 15,646 | 5.5 | 29.2 | 30.2 | 230,529 | 0.3 | 4.9 | 0.51 |

| Yes | 38,895 | 0.9 | 13.2 | 2.7 | 3,485 | 2.9 | 39.6 | 20.9 | 35,410 | 0.7 | 10.6 | 0.96 |

| Unknown | 290,562 | 0.6 | 6.0 | 2.4 | 19,364 | 4.5 | 27.5 | 29.4 | 271,198 | 0.3 | 4.4 | 0.45 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Year of delivery | ||||||||||||

| 2001 | 81,449 | 0.4 | 7.4 | 2.1 | 4,487 | 3.9 | 33.7 | 30.1 | 76,962 | 0.2 | 5.8 | 0.43 |

| 2002 | 82,433 | 0.4 | 7.0 | 2.2 | 4,746 | 4.3 | 30.3 | 30.8 | 77,687 | 0.2 | 5.6 | 0.46 |

| 2003 | 82,560 | 0.5 | 7.0 | 2.4 | 5,189 | 4.8 | 31.3 | 29.9 | 77,371 | 0.2 | 5.4 | 0.50 |

| 2004 | 80,784 | 0.6 | 6.8 | 2.5 | 5,433 | 5.0 | 29.4 | 29.8 | 75,351 | 0.3 | 5.2 | 0.53 |

| 2005 | 81,199 | 0.8 | 6.4 | 2.6 | 5,737 | 4.9 | 27.6 | 29.2 | 75,462 | 0.4 | 4.8 | 0.59 |

| 2006 | 83,653 | 0.8 | 6.2 | 2.7 | 6,369 | 5.0 | 27.4 | 28.1 | 77,284 | 0.5 | 4.5 | 0.55 |

| 2007 | 83,554 | 0.8 | 5.8 | 2.5 | 6,534 | 4.9 | 27.2 | 26.1 | 77,020 | 0.4 | 4.0 | 0.48 |

MAINTENCE: Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), Long acting beta-agonists (LABA), Leukotriene antagonist (LRA), Mast cell stabilizers, Methlyxanthines, combination of ICS & LABA.

RESCUE: Short acting beta-agonist (SABA), Anticholinergics (Ipratropium, Tiotropium), Ipratropium/albuterol.

Table 4 shows the prevalence of specific asthma medication dispensing among deliveries with at least one fill of any asthma medication (n=55,914). SABAs were the most commonly dispensed medication; 92% of deliveries with any asthma medication dispensing had a SABA dispensing (n=51,527). ICS were the second most commonly dispensed medication (25.2%) and the remaining medications were dispensed for less than 5% of the deliveries. During the study period (2001-2007) the prevalence of dispensing of several of the maintenance-only medications increased over time: LRA (1.3% to 7.4%), ICS (23.2% to 27.1%), and combination of ICS and LABA (0.1% to 6.1%). However, this finding was not evident among other maintenance-only medications. The prevalence of LABA dispensing decreased over the study period from 3.0% to 1.7%. Apart from a slight decrease in the use of SABA over the study period (94.5% to 90.3%), there was no strong indication of a trend in the prevalence of rescue-only medication dispensing over time.

Table 4.

Prevalence (%) of asthma medication dispensing among deliveries with at least one medication fill (n=55,914).

| Maintenance Medications |

Anticholinergics |

Rescue Medications |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | LABA | ICS | LRA | Mast cell stabilizers |

Methylxan -thines |

ICS & LABA |

Ipratropium, Tiotropium |

Ipratropium -albuterol |

SABA | |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Total, n | 55,914 | 1,581 | 14,116 | 2,464 | 241 | 413 | 2,113 | 874 | 891 | 51,527 |

| (%) | (100) | (2.8) | (25.2) | (4.4) | (0.4) | (0.7) | (3.8) | (1.6) | (1.6) | (92.1) |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Mother’s age at delivery | ||||||||||

| <18 | 2,262 | 1.1 | 20.6 | 8.0 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 5.0 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 93.4 |

| 18-24 | 16,605 | 1.6 | 17.6 | 5.9 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 4.2 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 93.5 |

| 25-34 | 27,261 | 3.1 | 27.1 | 3.6 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 3.5 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 91.8 |

| 35-45 | 9,786 | 4.5 | 34.1 | 3.3 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 3.4 | 1.9 | 1.1 | 90.5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Mother’s marital status | ||||||||||

| Married | 16,502 | 2.9 | 18.8 | 5.4 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 5.2 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 92.0 |

| Not Married | 12,470 | 1.5 | 12.9 | 9.0 | 0.4 | 1.5 | 6.7 | 1.7 | 3.2 | 92.4 |

| Unknown | 26,942 | 3.4 | 34.9 | 1.6 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 92.1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Mother’s education (yrs) | ||||||||||

| <=12 | 25,408 | 2.0 | 20.2 | 5.8 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 4.3 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 92.8 |

| >12 | 28,185 | 3.5 | 29.5 | 3.3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 3.3 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 91.6 |

| Unknown | 2,321 | 3.6 | 28.6 | 3.5 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 4.4 | 1.7 | 0.8 | 91.5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Mother’s race | ||||||||||

| White | 29,841 | 2.9 | 22.0 | 5.3 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 4.1 | 1.6 | 2.0 | 91.5 |

| Black/African American | 8,473 | 2.4 | 20.9 | 6.2 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 5.8 | 1.5 | 2.1 | 94.2 |

| Asian American | 3,655 | 2.3 | 32.7 | 1.5 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 91.6 |

| Hispanic | 10,135 | 2.8 | 32.1 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 93.3 |

| Native American | 191 | 5.8 | 25.7 | 4.2 | 0.0 | 2.1 | 1.0 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 95.3 |

| Other/unknown | 3,619 | 3.2 | 35.3 | 4.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 4.4 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 90.4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Mother’s smoking status | ||||||||||

| No | 23,352 | 3.2 | 25.8 | 4.3 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 4.4 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 92.1 |

| Yes | 6,567 | 1.0 | 11.8 | 6.7 | 0.2 | 1.6 | 4.9 | 2.1 | 4.5 | 91.9 |

| Unknown | 25,995 | 3.0 | 28.2 | 3.9 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 2.9 | 1.7 | 1.1 | 92.2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Year of delivery | ||||||||||

| 2001 | 8,019 | 3.0 | 23.2 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 94.5 |

| 2002 | 7,972 | 3.6 | 25.0 | 2.0 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 94.4 |

| 2003 | 8,187 | 4.1 | 24.6 | 3.2 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 2.7 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 93.4 |

| 2004 | 8,073 | 2.9 | 25.0 | 4.1 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 4.5 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 91.8 |

| 2005 | 7,971 | 2.3 | 25.3 | 6.4 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 6.2 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 90.5 |

| 2006 | 8,109 | 2.0 | 26.6 | 6.5 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 6.2 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 90.2 |

| 2007 | 7,583 | 1.7 | 27.1 | 7.4 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 6.1 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 90.3 |

Mav be double counting when mothers are on multiple medications.

NOTE: Ipratropium and Tiotropium are presented as Anticholinergic medications within a separate column from maintenance and rescue medications. Whereas in Table 3 they are defined as a rescue medication.

Number of dispensing across deliveries (any medication)

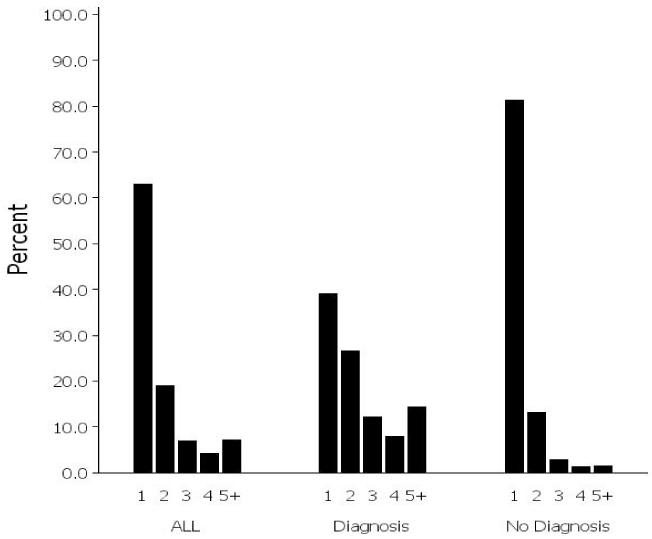

Figure 2 shows the distribution of the percentage of deliveries with 1, 2, 3, 4, and more than 5 dispensings of any asthma medication. Of the deliveries with any dispensing, 63% had only one dispensing, 19% had two dispensings, 7% had three dispensings, 4% had four dispensings, and 7% had five or more dispensings (Figure 2). However, among the deliveries with a maternal asthma diagnosis, 39% had one dispensing, 27% had two dispensings, 12% had three dispensings, 8% had four dispensings, and 14% had five or more dispensings. Of those deliveries without a maternal asthma diagnosis, 81% had only one dispensing, 13% had two dispensings, and the remaining categories of dispensings were all below 3% (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Distribution of deliveries based on the number of asthma medication dispensings (1, 2, 3, 4, 5+) among deliveries in which an asthma medication was dispensed (n=55,914) overall and stratified by asthma diagnosis. Distributions within each of the three groups total 100%.

Discussion

In this large cohort, we found that the prevalence of asthma diagnosis during pregnancy was 6.7% and increased slightly between 2001 and 2007. Based on National Health Interview Survey data, the prevalence of asthma among adult females in the United States was 9.7% in 2009, and from 2001 – 2009 there was an increase from 8.3% to 9.2% among all females (12). The prevalence of asthma diagnoses reported here (6.7%) is similar to that found in a previous study (6.5%) that used data from 140,299 deliveries of women aged 15 to 44 years with singleton gestations enrolled in the Tennessee Medicaid program from 1995 to 2003 (13). The prevalence of asthma diagnoses for the current study is lower than the prevalence reported by Kwon and colleagues for ‘current asthma’ during pregnancy (8.4%; 95% CI 7.4%-9.5%) using data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey (2000-2003) (1). The difference in the results of these studies may be due to incomplete capture of asthma diagnoses in administrative data in the current study, or differences in how “asthma” was defined and captured in the two studies. Similar to Kwon’s (1) findings, the overall prevalence of asthma among pregnant women within our cohort increased during the study period and was higher among younger women. Also consistent with our findings, a maternal morbidity study using National Hospital Discharge Survey data reported that counts of asthma as a “pre-existing medical condition at delivery” increased significantly from 1993-1997 to 2001-2005(14).

To date, there has been limited research on the prevalence of asthma medication use during pregnancy. A recent study of 61,252 pregnant women in Ireland investigated the prevalence of medication use during pregnancy and found that, of the women with a history of asthma, 62.9% reported using an asthma medication during pregnancy (15). This prevalence is in accordance with our findings: in our study, of the deliveries with an asthma diagnosis, 63% used asthma medication during pregnancy. A previous study across eight HMO sites within the HMO Research Network Center for Education and Research on Therapeutics (HMORN CERT) examined the prevalence of prescription drug use during pregnancy between 1996 and 2000 (note: these eight sites are part of MEPREP). This study reported that, in 4.9% of deliveries, albuterol (SABA, rescue-only medication) was used by the mother at least once during the 270 days prior to delivery (16). Similarly, in a more recent study, albuterol was among the top 20 drugs used during the first trimester with a prevalence of 2.2% (data from 1978 – 2008) (17). Although not directly comparable, we categorized albuterol as a SABA and found that 8.9% of deliveries (n=575,632), the mother had received a SABA dispensing (n=51,527) from 90 days prior to LMP through delivery.

Our study showed a decline in the prevalence of rescue-only medication dispensing over time, with a concomitant increase in dispensing of LRA, ICS, and combined LABA/ICS (maintenance medications). However, there was a decline in dispensing of LABA-only (maintenance medication). These trends are similar to previously reported national trends for asthma medication dispensing over time. The findings also align with current clinical guidelines that highlight the importance of maintenance medication use, particularly the recommendation to use combined LABA/ICS therapy in preference to LABA alone (18, 19). A recent study analyzed data from the National Ambulatory Care Survey and National Disease and Therapeutic Index between 1997 and 2009 to examine national trends of office-based asthma treatment. This study reported decreased use of SABA and LABA, and increased use of LRA, ICS, and LABA/ICS(18).

In the current study, many of the women filled asthma medications during pregnancy but did not have an asthma diagnosis. Characteristics of mothers with and without an asthma diagnosis varied by medication type, suggesting that there may be underlying reasons why a large percentage of mothers did not have an asthma diagnosis. Even though health records were searched for an asthma diagnosis from 180 days prior to pregnancy through delivery, it is possible that a diagnosis was not recorded. It is also possible that mothers with a prior asthma diagnosis did not have an encounter where the diagnosis was required for, or linked to, asthma medication prescriptions filled within the search timeframe used for this study (i.e. 180 days prior to pregnancy through delivery). Conversely, women without an asthma diagnosis may have not had asthma, but were prescribed albuterol for wheezing associated with an upper respiratory infection.

Of the deliveries with any asthma medication dispensing, 63% had only one dispensing, and the percentage of deliveries with only one dispensing was much higher for mothers without an asthma diagnosis (81%) compared to mothers with a diagnosis (39%). The reasons for a higher prevalence of only one dispensing among women without an asthma diagnosis are unclear. One possible hypothesis is that certain leukotriene inhibiting asthma medications (LRA) are also approved for treatment of other allergic symptoms, such as seasonal allergies (allergic rhinitis) (20), however our study did not examine diagnoses for allergic rhinitis. Therefore, women without an asthma diagnosis may have been prescribed an LRA for allergic symptoms and only filled the prescription once, as deemed necessary for symptom relief. Although we did not investigate the number of dispensings for particular medication types, other research has shown that, of women with asthma who used ICS, 72% filled only one prescription during pregnancy (13).

Strengths and limitations

The major strength of our study is that we analyzed data from a large cohort that is ethnically and geographically diverse and represents a large number of health plans. The use of pharmacy data eliminates recall bias; however, dispensing data do not indicate whether mothers actually ingested or inhaled the medication. There are several limitations to our study. Our results show an association between SABA dispensing and preterm birth and low birth weight. However, this finding may be driven by terbutaline, a SABA used “off label” to treat preterm labor. There was a large percentage of ‘unknown/missing’ data for smoking status and marital status, and the results presented for these characteristics should be interpreted with caution. Because this is a prevalence study where we did not focus on the effect of asthma medications, we did not classify asthma as intermittent vs. persistent, or mild/moderate/severe, and therefore, cannot report on appropriate use of the medications. Lastly, a large percentage of deliveries had only one dispensing of asthma medication, and this percentage was largely driven by deliveries without a maternal asthma diagnosis.

Conclusion

Our study describes the prevalence of asthma diagnoses and asthma medication use during pregnancy in a large, nationally representative cohort using a unique resource composed of several large, linked, automated health plan databases. Consistent with previous research, the prevalence of asthma diagnoses increased over time, and the use of LRA, ICS, and LABA/ICS (maintenance medications) increased over time, while there was a decline in the use of LABA-only maintenance medications. There was also a decrease in the use of rescue-only medications over time. This study highlights the potential to conduct detailed large-scale studies investigating the adverse maternal and fetal effects stemming from the use of individual asthma medications during pregnancy within MEPREP.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Group Health Research Institute (Washington), Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute (Massachusetts), HealthPartners Research Foundation (Minnesota), Kaiser Permanente Colorado, Kaiser Permanente Northwest (Oregon, Washington), Meyers Primary Care Institute (Massachusetts), Lovelace Clinic Foundation (New Mexico), Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Kaiser Permanente Southern California, TennCare Bureau, and the Tennessee Department of Health for providing study data.

We would also like to thank the MEPREP programmers at each site for their time and effort in extracting the data.

Funding/Support

This study was supported through funding from contracts HHSF223200510012C, HHSF223200510009C, and HHSF223200510008C from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (Office of Surveillance and Epidemiology, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research). Dr. Dublin was supported by National Institute on Aging grant K23AG028954.

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and are not intended to convey official U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) policy or guidance. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging or the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- ICS

Inhaled corticosteroid

- LABA

Long acting beta agonist

- LMP

Last menstrual period

- LRA

Leukotriene receptor antagonist

- MEPREP

Medication Exposure in Pregnancy Risk Evaluation Program

- SABA

Short acting beta agonist

APPENDIX A: List of asthma medications

| MAINTENANCE MEDICATIONS | |

| Combinations (ICS & LABA) | Mast cell stabilizers |

| BUDESONIDE/FORMOTEROL | CROMOLYN |

| FLUTICASONE/SALMETEROL | NEDOCROMIL |

| Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) | Long acting beta-agonists (LABA) |

| BECLOMETHASONE | ARFORMOTEROL |

| BUDESONIDE | FORMOTEROL |

| FLUNISOLIDE | SALMETEROL |

| FLUNISOLIDE/MENTHOL | |

| FLUTICASONE | Leukotriene antagonist (LRA) |

| MOMETASONE | MONTELUKAST |

| TRIAMCINOLONE | ZAFIRLUKAST |

| ZILEUTON | |

| Methylxanthines | |

| AEROLATE | THEOP/ISOPROTERENOL/EPD/KI/PB |

| AMINOPHYLLIN/EPHED/POT IOD/PB | THEOPHYLL/CAFF/AA13/CINN/HC135 |

| AMINOPHYLLINE | THEOPHYLL/EPHED HCL/PHENOBARB |

| AMINOPHYLLINE/EPHED/AMOBARB | THEOPHYLL/EPHED/BUTABARBITAL |

| AMINOPHYLLINE/EPHED/PHENOBARB | THEOPHYLL/EPHED/POT IODIDE/PB |

| AMINOPHYLLINE/EPHEDRINE | THEOPHYLLINE |

| AMINOPHYLLINE/PHENOBARB | THEOPHYLLINE-EPHED-BUTABA |

| AMINOPHYLLINE/QUININE | THEOPHYLLINE-EPHED-PHENOB |

| DYPHYLLINE | THEOPHYLLINE-EPHEDRINE |

| DYPHYLLINE-EPHEDRINE-PHEN | THEOPHYLLINE-EPHEDRINE-GG |

| GUAIFEN/DYPHYLLIN/EPHED/PB | THEOPHYLLINE-EPHEDRINE-PB |

| GUAIFEN/THEOP ANHYD/P-EPHED | THEOPHYLLINE-GUAIFENESIN |

| GUAIFENESIN/DYPHYLLINE | THEOPHYLLINE-IODINATED GL |

| GUAIFENESIN/OXTRIPHYLLINE | THEOPHYLLINE-KI |

| GUAIFENESIN/THEOPHYLLINE | THEOPHYLLINE-PSE-GG |

| OXTRIPHYLLINE | THEOPHYLLINE/DIETARY SUP.CMB9 |

| OXTRIPHYLLINE-GUAIFENESIN | THEOPHYLLINE/EPHED/HYDROXYZINE |

| THEOPHYLLINE/POTASSIUM IODIDE | |

| RESCUE MEDICATIONS | |

| Combinations | Short acting beta-agonists |

| IPRATROPIUM/ALBUTEROL | ALBUTEROL |

| BITOLTEROL | |

| Anticholinergics | ISOETHARINE |

| IPRATROPIUM | ISOPROTERENOL |

| TIOTROPIUM | |

| LEVALBUTEROL | |

| METAPROTERENOL | |

| PIRBUTEROL | |

| TERBUTALINE | |

Footnotes

Contact author

Contact author blinded as per request of the journal

References

- 1.Kwon HL, Belanger K, Bracken MB. Asthma prevalence among pregnant and childbearing-aged women in the United States: estimates from national health surveys. Ann. Epidemiol. 2003;13(5):317–24. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(03)00008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dombrowski MP, Schatz M. Asthma in pregnancy. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010;53(2):301–10. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181de8906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Managing Asthma During Pregnancy: Recommendations for Pharmacologic Treatment: National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. NIH Publication No. 055232005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakhireva LN, Schatz M, Chambers CD. Effect of maternal asthma and gestational asthma therapy on fetal growth. J. Asthma. 2007;44(2):71–6. doi: 10.1080/02770900601180313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Namazy JA, Schatz M. Pregnancy and asthma: recent developments. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2005;11(1):56–60. doi: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000148568.20273.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chambers C. Safety of asthma and allergy medications in pregnancy. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2006;26(1):13–28. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2005.10.001. doi:10.1016/j.iac.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andrade SE, Davis RL, Cheetham TC, et al. Medication Exposure in Pregnancy Risk Evaluation Program. Maternal Child Health Journal. 2012;16(7):1349–54. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0902-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, et al. Births: final data for 2007. Natl. Vital Stat. Rep. 2010;58(24):1–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper WO, Hernandez-Diaz S, Arbogast PG, et al. Major congenital malformations after first-trimester exposure to ACE inhibitors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354(23):2443–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raebel MA, Ellis JL, Andrade SE. Evaluation of gestational age and admission date assumptions used to determine prenatal drug exposure from administrative data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14(12):829–36. doi: 10.1002/pds.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toh S, Mitchell AA, Werler MM, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of computerized algorithms to classify gestational periods in the absence of information on date of conception. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2008;167(6):633–40. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Vital Signs: Asthma Prevalence, Disease Characteristics, and Self-Management Education — United States, 2001-2009. MMWR weekly. 2011;60(17) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Enriquez R, Griffin MR, Carroll KN, et al. Effect of maternal asthma and asthma control on pregnancy and perinatal outcomes. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2007;120(3):625–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berg CJ, Mackay AP, Qin C, et al. Overview of maternal morbidity during hospitalization for labor and delivery in the United States: 1993-1997 and 2001-2005. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;113(5):1075–81. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181a09fc0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cleary BJ, Butt H, Strawbridge JD, et al. Medication use in early pregnancy-prevalence and determinants of use in a prospective cohort of women. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19(4):408–17. doi: 10.1002/pds.1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andrade SE, Gurwitz JH, Davis RL, et al. Prescription drug use in pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004;191(2):398–407. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mitchell AA, Gilboa SM, Werler MM, et al. Medication use during pregnancy, with particular focus on prescription drugs: 1976-2008. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higashi A, Zhu S, Stafford RS, et al. National Trends in Ambulatory Asthma Treatment, 1997-2009. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1796-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma: National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. NIH Publication No. 08-5846.2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scow DT, Luttermoser GK, Dickerson KS. Leukotriene inhibitors in the treatment of allergy and asthma. Am. Fam. Physician. 2007;75(1):65–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]