ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE

To perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials evaluating the efficacy and safety of midodrine in orthostatic hypotension (OH).

METHODS

We searched major databases and related conference proceedings through June 30, 2012. Two reviewers independently selected studies and extracted data. Random-effects meta-analysis was used to pool the outcome measures across studies.

RESULTS

Seven trials were included in the efficacy analysis (enrolling 325 patients, mean age 53 years) and two additional trials were included in the safety analysis. Compared to placebo, the mean change in systolic blood pressure was 4.9 mmHg (p = 0.65) and the mean change in mean arterial pressure from supine to standing was −1.7 mmHg (p = 0.45). The change in standing systolic blood pressure before and after giving midodrine was 21.5 mmHg (p < 0.001). A significant improvement was seen in patients’ and investigators’ global assessment symptoms scale (a mean difference of 0.70 [95 % CI 0.30–1.09; p < 0.001] and 0.80 [95 % CI 0.76–0.85; p < 0.001], respectively). There was a significant increase in risk of piloerection, scalp pruritis, urinary hesitancy/retention, supine hypertension and scalp paresthesia after giving midodrine. The quality of evidence was limited by imprecision, heterogeneity and increased risk of bias.

CONCLUSION

There is insufficient and low quality evidence to support the use of midodrine for OH.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2520-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: orthostatic hypotension, midodrine, systematic review, meta-analysis, efficacy, safety

INTRODUCTION

Orthostatic hypotension (OH) is a chronic condition seen in neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, multiple system atrophy, pure autonomic failure, and in individuals with peripheral neuropathies and ganglionopathy.1 OH is characterized by inability to maintain blood pressure (BP) in the standing position, which can lead to lightheadedness, weakness, dizziness, difficulty in concentrating, palpitation, anxiety, near syncope and syncope.2,3 According to the latest consensus, OH is defined as a sustained reduction of systolic blood pressure (SBP) of at least 20 mm Hg, or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) of 10 mm Hg within 3 minutes of standing or head-up tilt (HUT) to at least 60°.1 A reduction in SBP of 30 mm Hg may be a more appropriate criterion for OH in patients with supine hypertension, as the orthostatic BP fall is dependent on the baseline BP.1 OH may be symptomatic or asymptomatic, but most patients with asymptomatic OH have clinical manifestation when exposed to increased stress such as meals, exercise and during increased temperature exposure.3

Management of OH includes non-pharmacological (such as compression of venous capacitance beds, physical counter maneuvers and intermittent water bolus treatment) and pharmacological interventions. However, non-pharmacological management alone is rarely adequate, as orthostatic stress varies with meals, time of day, ambient temperature and other orthostatic stress.3 Therefore, pharmacological treatment plays a crucial role in OH management. Midodrine (α1 adrenoreceptor agonist) is the only US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drug that has shown to improve OH and clinical symptoms in double-blind placebo-controlled trials.3 Midodrine was approved by the FDA in 1996 through the agency’s accelerated approval program, based on limited evidence.5–8

The FDA approved midodrine, requiring post marketing studies to document a clinical benefit; however, such studies were never submitted to FDA.6,7 The FDA threatened to withdraw midodrine from the market but did not, due to concerns raised by patients taking midodrine and treating physician who cited the absence of an alternative medication.6,7 Currently, the FDA has asked manufacturing companies to conduct more trials to evaluate the efficacy of midodrine in improving the OH symptoms.8 A challenge to such trials is that midodrine helps patients with severe OH due to autonomic failure, and most of these patients are very sick with limited life span. Recruiting such subjects in these trials is difficult due to severe disease, multiple medications, and difficulty in follow-up. In addition, patients with OH have multiple symptoms that may mask the benefit of midodrine.8

Clinical trials of midodrine efficacy in OH have yielded mixed results. Therefore, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of all the available randomized clinical trials to summarize the effect of midodrine on SBP, mean arterial pressure (MAP) and symptom improvement in patients with OH. A secondary objective of this meta-analysis was to assess the safety of midodrine, by analyzing the incidence of adverse events in patients with OH.

METHODS

Data Sources and Search

A comprehensive search through the OVID interface was conducted for Medline In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycInfo, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Scopus. An expert librarian (PJE) with input from the study team designed and executed the search strategy through June 30, 2012, and updated on May 8, 2013. We also searched for the databases of ongoing clinical trials (e.g. http://www.controlled-trials.com/ or http://clinicaltrials.gov/) to identify the potential eligible studies. Heading terms used in the search included “midodrine”, “hypotension” and “orthostatic”. Search was performed irrespective of language of publication and was limited to human subjects and controlled clinical trials. The complete search strategy is available as an “Online Appendix Search Strategy”. To minimize publication bias, references cited in potentially eligible articles and conference proceedings of major neurology, pharmacology, autonomic and neurosurgical organizations were hand-searched. Relevant abstracts from these meetings were used to search for the full articles in PubMed.

Study Selection

Two reviewers (AKP and BS) independently screened the titles and abstracts of potentially eligible articles. Subsequently, the full texts of potentially eligible articles were reviewed separately by the same two reviewers. We selected all prospective clinical trials comparing the midodrine with control/placebo in patients with OH and describing the details of the midodrine dose and route (bolus/infusion). We did not include case reports, case series or any observational studies. OH due to medications or other non-neurogenic causes, as well as studies conducted in the pediatric population, were excluded. Inter-reviewer agreement on study selection was assessed with Cohen’s weighted κ,9 and a third reviewer (MHM) resolved disagreements.

Quality Assessment

To evaluate the quality of the eligible randomized trials, we determined the adequacy of randomized sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, care givers and outcome assessors, and the extent of loss to follow-up. The quality indicators described below are derived from the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool.10 Quality indicators were 1) selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate generation of a randomized sequence; 2) selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate concealment of allocations prior to assignment; 3) performance bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by participants and personnel during the study; 4) detection bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by outcome assessors; 5) attrition bias due to amount, nature or handling of incomplete outcome data; 6) reporting bias due to selective outcome reporting; and 7) bias due to problems not covered elsewhere in the table. Responses for each criterion were: 0 = low risk of bias, 1 = high risk of bias, 2 = unclear risk of bias. The quality assessment of the clinical trials methodology was performed by two investigators (AKP, BS) independently, and a third reviewer (MHM) was involved to resolve any disagreements. The quality of the evidence for each outcome was further assessed according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) working group guidelines.11,12

Data Extraction

Data were extracted from selected trials by two reviewers (AKP, BS) in duplicate, using a predesigned form. The following data were extracted: trial characteristics (author, country, number of participants, trial design and description of participants), participants’ selection (inclusion and exclusion criteria), drug dosages, change in SBP and MAP, symptom improvement, side effects and study conclusion. Authors of trials with incomplete outcome data were contacted for missing information and clarification of results. Outcomes of interest were mean difference in global symptoms assessment scales assessed by patients and investigators, mean difference of change of SBP and MAP, and risk ratio for each adverse event with 95 % confidence interval (CI). All the disagreements in data extraction were resolved by consensus in the presence of a third investigator (MHM).

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Continuous variables are reported as means with standard deviation (SD) or medians with interquartile range (IQR), while categorical variables are expressed as frequency and proportions. Random-effects meta-analysis was used to pool the different measures of the outcomes.13 The I-squared static and Cochrane Q test were used to assess heterogeneity of the treatment effect among trials for each outcome. I-squared value > 50 % indicates substantial heterogeneity that is due to real differences in study populations, protocols, interventions, and/or outcomes, and a conservative p value < 0.10 of the Cochrane Q test suggests that the heterogeneity is beyond random error or chance.14 While analyzing the data from cross-over studies, each arm was considered as a separate arm because all the studies had appropriate washout periods with no carry-on effects of drugs. For pre-post and cross-over trials, placebo/baseline measurements were taken as control, while optimal dose midodrine measurements were taken as intervention outcomes. All statistical analyses were performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis version 2 (2005, Biostat Inc, Englewood, NJ).

RESULTS

Study Selection

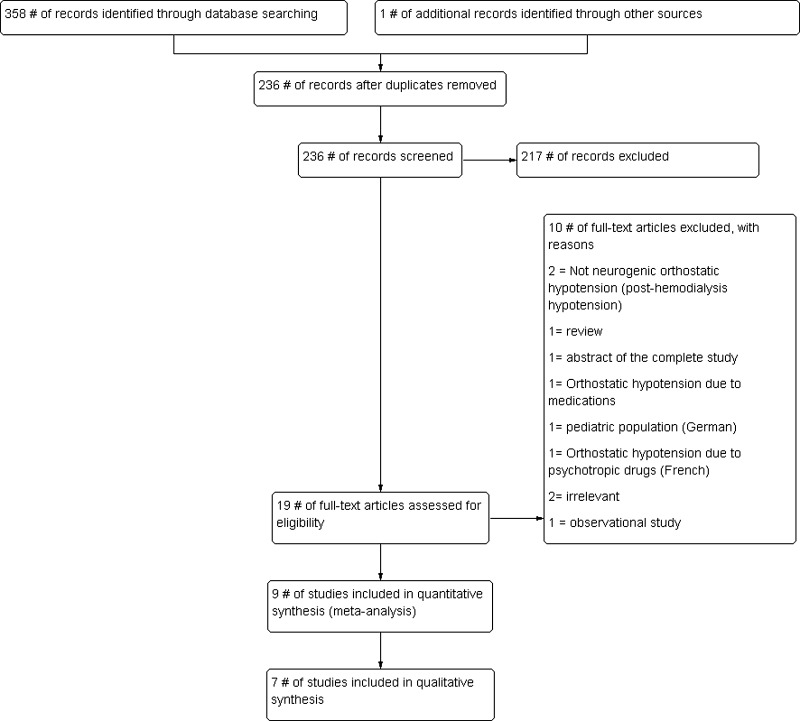

A total of 338 studies were identified through the search strategy and one additional study was identified from the conference proceedings. Preliminary screening (screening titles and abstracts) excluded 201 studies (Fig. 1). Two reviewers had an agreement of kappa = 0.88 (95 CI 0.77–1.00) in abstract screening phase. The full text of each of the remaining 18 studies was assessed in depth for eligibility; of these, nine were included for data synthesis (six with SBP,15–20 one with mean BP only21 and two with adverse events only22,23), with an excellent inter-reviewer agreement, kappa = 0.89 (95 % CI, 0.66–1.00). Seven studies were included in qualitative data synthesis15–21 (two studies included in adverse events analyses only were excluded from quality assessment). Three authors were contacted for desirable/missing data; however, none could provide the required data.15,16,23

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for study selection.

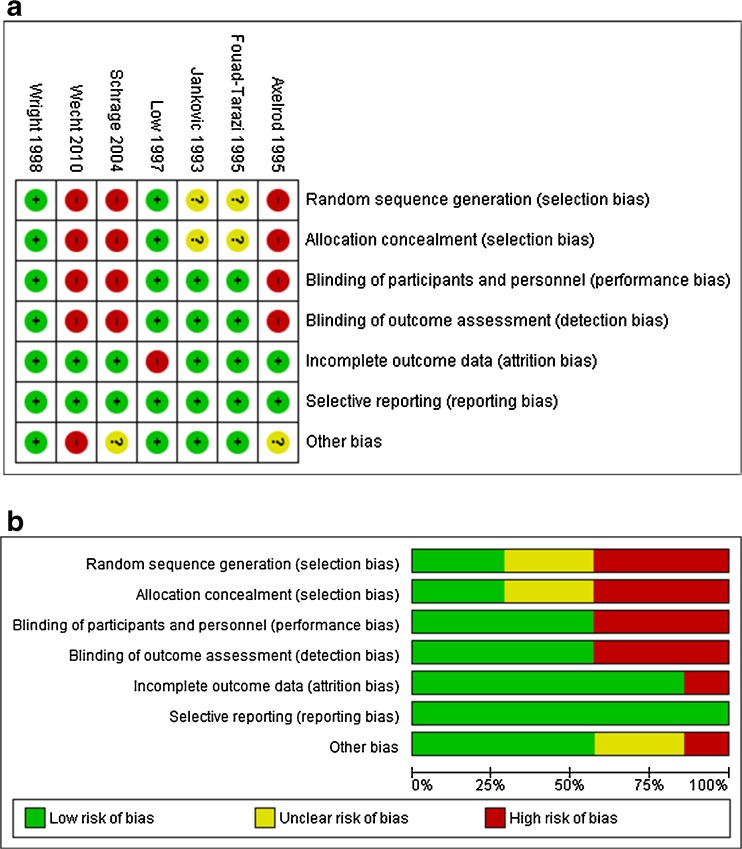

Characteristics of Included Studies and the Risk of Bias

The characteristics of the nine included studies are presented in Table 1. Seven trials included in the primary analysis (effect of midodrine on BP) were conducted across 49 centers in the USA and enrolled a total of 325 patients. Mean age was 53.2 ± 11.7 years and 48 % were females. The remaining two trials reported only adverse events and did not provide sufficient data for effectiveness analysis.22,23 Three of the trials had a cross-over design (Table 1). The included studies varied in terms of their methodological quality. Studies by Fouad-Tarazi et al. and Wright et al. reported better overall quality measures.15,20 A detailed quality assessment of the included studies with overall judgment about the risk of bias is depicted in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Studies Included in Meta-Analysis

| Author, Year, Country | Design | Participant’s Characteristics | Total Patients | Optimal Dose of Midodrine | Primary Outcome Measured | Secondary Outcomes Measured |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wecht 2012, USA | Open prospective pre-post dose response trial | Chronic tetraplegia, neurologically stable for 9 years post-injury, non-smokers, off medications with known autonomic effects | 10 | 10 mg | SBP and MAP during 60 min of HUT | Symptoms during HUT |

| Schrage 2004, USA | Open pre-post study | Pure autonomic failure or autonomic neuropathy with orthostatic hypotension, non-obese and free of systemic dysfunctions | 14 | 10 mg | SBP and MBP recovery in exercise-induced hypotension on standing | Effect of midodrine on HR, forearm blood flow, total peripheral resistant, and catecholamine level |

| Fouad-Tarazi 1995, USA | Double-blind, blocked, randomized crossover design | MSA, idiopathic orthostatic hypotension | 8 | 10 mg | Change in SBP/DBP from supine to standing and standing BP before and after intervention | Frequency of ability to stand, standing SBP > 80 mm Hg and adverse effects |

| Jankovic 1993, USA | Double blinded placebo-controlled parallel group study | Bradbury-Eggleston Syndrome, Shy-Drager Syndrome, diabetes, Parkinson’s Disease, amyloidosis, neuropathies | 97 | 10 mg | Change in SBP/DBP from supine to standing and standing BP before and after intervention | Orthostatic symptoms improvement and adverse effects |

| Low 1977, USA | Double-blind, randomized, parallel group study | MSA, Bradbury Eggleston syndrome, diabetic autonomic neuropathy, Parkinson’s disease | 162 | 10 mg | Change in standing BP and symptoms of lightheadedness | Global symptoms assessment and adverse effects |

| Wright 1998, USA | Double blinded, randomized placebo-controlled, four-way crossover trial | MSA, Parkinson’s disease, diabetes mellitus, pure autonomic failure | 25 | 10 mg | Change in standing SBP | Global symptoms assessment and adverse effects |

| Axelrod 1995, USA | Open crossover clinical trial | Familial dysautonomia | 9 | Variable | Change in mean BP | Heart rate responsiveness (using beats/min and corrected QT-interval measurements) and renal blood flow |

| Hoeldtke* 1997, USA | Open pre-post study | Autonomic neuropathy and chronic orthostatic hypotension | 16 | 10 mg | Standing time and standing BP | Adverse events |

| Kaufmann* 1988, USA | Open pre-post study for midodrine, double blinded crossover trial for midodrine + fludrocortisone vs. placebo + fludrocortisone | MSA, Shy-Drager syndrome, Idiopathic orthostatic hypotension (Bradbury-Eggleston syndrome) | 7 | 10 mg | Change in upright mean arterial | Adverse events |

SBP Systolic blood pressure, MAP means arterial pressure, HUT Head-up tilt, HR heart rate, MSA Multisystem Atrophy

*Studies included for adverse event analysis only

Figure 2.

a Risk of bias summary: review authors’ judgments about each risk of bias item for each included study. b Risk of bias graph: review authors’ judgments about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Meta-analysis

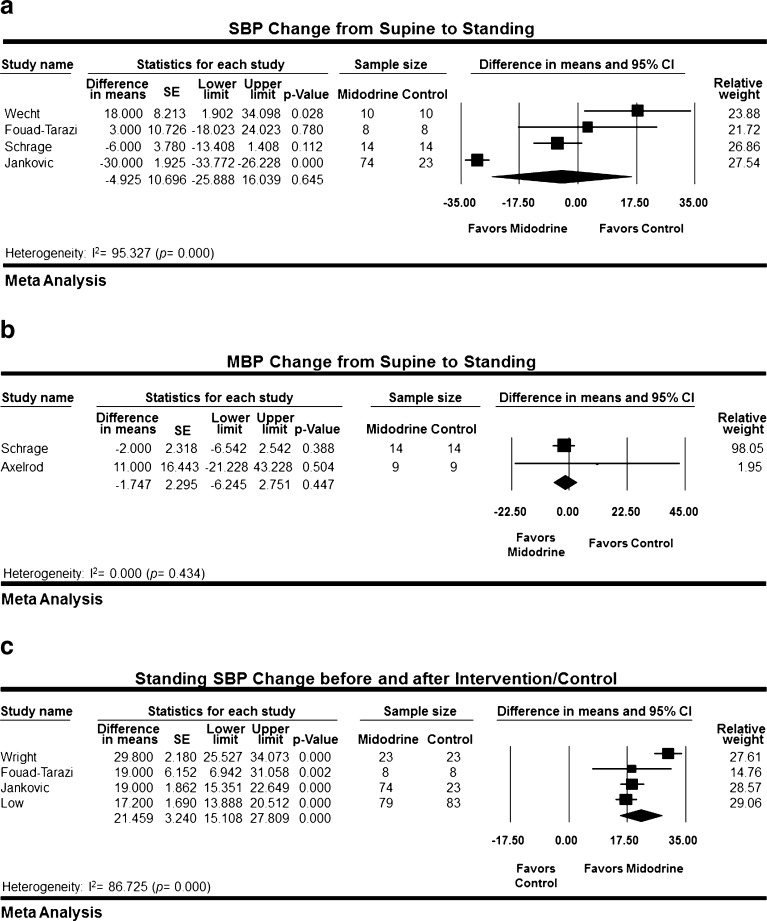

The change in BP was reported in three different ways across the studies: a change in SBP from supine to standing position comparing midodrine to placebo, a change in MAP from supine to standing comparing midodrine to placebo, and a change in standing SBP before and after the intervention.

Wecht et al., Fouad-Tarazi et al., Schrage et al. and Jankovic et al. reported change in SBP from supine to standing position between midodrine and placebo group in 129 patients.15,16,18,19 Jankovic et al. administrated midodrine to 74 patients and placebo to 23 different patients; while in the other three studies, the same patients received midodrine and placebo separated by a wash-out period. The mean difference in SBP change from supine to standing between placebo and midodrine by random-effects meta-analysis was not statistically significant (4.925 mmHg; 95 % CI −25.89 to16.04; p = 0.65) (Fig. 3a). The analysis was associated with significant heterogeneity (I-square = 95 %; p < 0.001).

Figure 3.

a Systolic blood pressure change from supine to standing. b Mean blood pressure change from supine to standing. c Standing systolic blood pressure change before and after intervention/placebo.

Schrage et al. and Axelrod et al. compared change in MAP from supine to standing position in 23 patients who received placebo and midodrine separated by a wash out period.18,21 The mean difference in MAP was not statistically significant (1.747 mmHg; 95 % CI −6.24 to 2.75; p = 0.45) (Fig. 3b). No heterogeneity was detected in this analysis (I-square = 0 %; p = 0.43).

Four studies reported the change in standing SBP before and after midodrine administration in 290 patients.15–17,20 Jankovic et al. and Low et al. administrated midodrine to 153 patients and placebo to 106 patients, while the other two studies used a cross-over design. Random-effects meta-analysis demonstrated a statistically significant increase in mean standing SBP (21.46 mmHg; 95 % CI 15.11 to 27.81; p < 0.001) (Fig. 3c). Significant heterogeneity was observed in this analysis (I-square =87; p < 0.001).

Only two studies (Low et al. and Wright et al.) reported the global assessment symptoms scale (by patients and investigators).17,20 Patients’ scale showed a mean difference of 0.70 (95 % CI 0.30–1.09; p < 0.001), while Investigators’ scale showed a mean difference of 0.80 (95 % CI 0.76–0.85; p < 0.001), consistent with a favorable effect of midodrine on symptoms (Fig. 4). No heterogeneity was observed in the investigators’ scale analysis (I-square = 0.000; p = 1.00), but significant heterogeneity was detected in the patients’ scale analysis (I-square = 97 %; p < 0.001).

Figure 4.

a Global symptoms assessment scale—patients. b Global symptoms assessment scale—investigators.

Studies varied in terms of reporting adverse events. Random-effects meta-analyses demonstrated increased incidence of piloerection, scalp pruritis, urinary hesitancy/retention, supine hypertension and scalp paresthesia among patients receiving midodrine with pooled risk ratios of 10.53, 6.45, 5.85, 6.38 and 8.28; respectively (online appendix A, B, C, D, E). No heterogeneity was detected among these meta-analyses (I-square = 0.00 for each adverse event, online appendix A, B, C); however, tests for heterogeneity were underpowered.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated the efficacy and adverse events associated with using midodrine to treat OH. Our meta-analysis suggest that change in MBP and SBP from supine to standing position did not differ between midodrine and control. Although there was a trend towards the improvement of MBP and SBP after the midodrine, the effect did not reach a statistical significance. A significant improvement in standing SBP after the intervention was observed among the midodrine group compared to controls; however, significant heterogeneity was observed in the both of these analyses. These findings are similar to a previous review by Logan et al., who reported improvement in standing blood pressure with the worsening of postural drop, but included a limited number of studies without meta-analysis.24

The global assessment symptoms scale used by patients and investigators was consistent with improvement in symptoms after using midodrine; however, this outcome was reported by only two studies.17,20 The commonly reported adverse events were piloerection, scalp pruritis and paresthesia, urinary hesitancy/retention and supine hypertension. The incidence of adverse events was significantly higher among the midodrine group as compared to the control/placebo group.

Patient population and indication varied across the studies (e.g. chronic tetraplegics, exercise-induced hypotension); however, a smaller number of studies did not allow us to do subgroup analysis. The validity of the global symptoms scale used to assess symptom improvement by two studies is uncertain; therefore, more studies are required. The global symptoms scale incorporates improvement in lightheadedness, standing time and orthostatic energy level, enhancing the activities of daily living.16 The overall GRADE quality of evidence for global symptoms assessment by the investigator was moderate, and low for global symptoms assessment scale by patients.

Patients on midodrine had higher risk of adverse events compared to the controls, and results were homogenous for all the adverse events. Due to severe adverse events, discontinuation of medication was required in five patients (6.8 %, four supine hypertension and one head fullness) in the study by Jankovic et al.16 Similarly, in the Low et al. study, 23 (14 %) patients dropped out due to different adverse events such as supine hypertension, pilomotor reactions, urinary urgency and retention.17 Wright et al. also reported discontinuation of one patient due to excessive hypertension; however, that was after receiving a 20 mg dose.20 Therefore, patients should be informed about possible adverse events prior to taking the drug. However, the best evidence of side effects is in fact obtained from large observational studies and not RCTs.25 Because of the limited efficacy and higher risk for adverse events, midodrine should be used with caution by physicians with expertise and familiarity with this condition.

The strength of our meta-analysis is the comprehensive database search to identify all the potential studies. Corresponding authors of the studies were contacted for missing information; however, they could not provide the missing information due to various reasons, notably the unavailability of the study data, as the studies were conducted long ago.

The main limitations of this systematic review and meta-analysis are the small number of included studies and the variation in primary outcome reporting methods. Therefore, we were unable to pool all the studies for final analysis, and overall, results were imprecise. Inferences were also limited by large heterogeneity. The small number of studies and observed heterogeneity limited the ability to investigate the effect of publication bias. Meta-analyses with less than 20 studies have little statistical power to detect publication bias.26 Reporting bias is in fact quite likely (considering that many studies did not report all relevant outcomes).

CONCLUSION

There is insufficient and low quality evidence to recommend the use of midodrine for orthostatic hypotension. Midodrine may improve standing SBP and global symptoms, but has no significant benefit on supine to standing SBP and MBP, and caused a higher incidence of adverse events.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(PDF 71 kb)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Christian Jeng-Singh (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN) for his help in the translation of the German articles.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Funding

None.

Footnotes

Ajay K. Parsaik and Balwinder Singh contributed equally to this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Freeman R, Wieling W, Axelrod FB, et al. Consensus statement on the definition of orthostatic hypotension, neurally mediated syncope and the postural tachycardia syndrome. Auton Neurosci. 2011;161:46–8. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Low PA. Update on the evaluation, pathogenesis, and management of neurogenic orthostatic hypotension: introduction. Neurology. 1995;45:S4–5. doi: 10.1212/WNL.45.6_Suppl_6.S4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Low PA, Singer W. Management of neurogenic orthostatic hypotension: an update. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:451–8. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70088-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Somberg JC. The midodrine withdrawal. Am J Ther. 2010;17:445. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e3181f7e4ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dhruva SS, Redberg RF. Accelerated approval and possible withdrawal of midodrine. JAMA. 2010;304:2172–3. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitka M. FDA takes slow road toward withdrawal of drug approved with fast-track process. JAMA. 2011;305:982–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitka M. Trials to address efficacy of midodrine 18 years after it gains FDA approval. JAMA. 2012;307:1124–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Somberg JC. The midodrine withdrawal. Am J Ther. 2010;17:445. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e3181f7e4ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas. 1960;20:37–46.

- 10.Higgins JP, Green S, Eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011 Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org 2011.

- 11.Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004;328:1490. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Vist GE, Falck-Ytter Y, Schunemann HJ. What is “quality of evidence” and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ. 2008;336:995–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39490.551019.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fouad-Tarazi FM, Okabe M, Goren H. Alpha sympathomimetic treatment of autonomic insufficiency with orthostatic hypotension. Am J Med. 1995;99:604–10. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(99)80246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jankovic J, Gilden JL, Hiner BC, et al. Neurogenic orthostatic hypotension: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study with midodrine. Am J Med. 1993;95:38–48. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(93)90230-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Low PA, Gilden JL, Freeman R, Sheng KN, McElligott MA. Efficacy of midodrine vs. placebo in neurogenic orthostatic hypotension. A randomized, double-blind multicenter study. Midodrine Study Group. JAMA. 1997;277:1046–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03540370036033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schrage WG, Eisenach JH, Dinenno FA, et al. Effects of midodrine on exercise-induced hypotension and blood pressure recovery in autonomic failure. J Appl Physiol. 2004;97:1978–84. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00547.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wecht JM, Rosado-Rivera D, Handrakis JP, Radulovic M, Bauman WA. Effects of midodrine hydrochloride on blood pressure and cerebral blood flow during orthostasis in persons with chronic tetraplegia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91:1429–35. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wright RA, Kaufmann HC, Perera R, et al. A double-blind, dose-response study of midodrine in neurogenic orthostatic hypotension. Neurology. 1998;51:120–4. doi: 10.1212/WNL.51.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Axelrod FB, Krey L, Glickstein JS, Weider Allison J, Friedman D. Preliminary observations on the use of midodrine in treating orthostatic hypotension in familial dysautonomia. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1995;55:29–35. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(95)00023-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoeldtke RD, Horvath GG, Bryner KD, Hobbs GR. Treatment of orthostatic hypotension with midodrine and octreotide. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:339–43. doi: 10.1210/jc.83.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaufmann H, Brannan T, Krakoff L, Yahr MD, Mandeli J. Treatment of orthostatic hypotension due to autonomic failure with a peripheral alpha-adrenergic agonist (midodrine) Neurology. 1988;38:951–6. doi: 10.1212/WNL.38.6.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Logan IC, Witham MD. Efficacy of treatments for orthostatic hypotension: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2012;41:587–94. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afs061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pathak A, Raoul V, Montastruc JL, Senard JM. Adverse drug reactions related to drugs used in orthostatic hypotension: a prospective and systematic pharmacovigilance study in France. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;61:471–4. doi: 10.1007/s00228-005-0941-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sterne JA, Gavaghan D, Egger M. Publication and related bias in meta-analysis: power of statistical tests and prevalence in the literature. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:1119–29. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00242-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 71 kb)