ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Patient navigator (PN) programs can improve breast cancer screening in low income, ethnic/racial minorities. Refugee women have low breast cancer screening rates, but it has not been shown that PN is similarly effective.

OBJECTIVE

Evaluate whether a PN program for refugee women decreases disparities in breast cancer screening.

DESIGN

Retrospective program evaluation of an implemented intervention.

PARTICIPANTS

Women who self-identified as speaking Somali, Arabic, or Serbo-Croatian (Bosnian) and were eligible for breast cancer screening at an urban community health center (HC). Comparison groups were English-speaking and Spanish-speaking women eligible for breast cancer screening in the same HC.

INTERVENTION

Patient navigators educated women about breast cancer screening, explored barriers to screening, and tailored interventions individually to help complete screening.

MAIN MEASURES

Adjusted 2-year mammography rates from logistic regression models for each calendar year accounting for clustering by primary care physician. Rates in refugee women were compared to English-speaking and Spanish-speaking women in the year before implementation of the PN program and over its first 3 years.

RESULTS

There were 188 refugee (36 Somali, 48 Arabic, 104 Serbo-Croatian speaking), 2,072 English-speaking, and 2,014 Spanish-speaking women eligible for breast cancer screening over the 4-year study period. In the year prior to implementation of the program, adjusted mammography rates were lower among refugee women (64.1 %, 95 % CI: 49–77 %) compared to English-speaking (76.5 %, 95 % CI: 69 %–83 %) and Spanish-speaking (85.2 %, 95 % CI: 79 %–90 %) women. By the end of 2011, screening rates increased in refugee women (81.2 %, 95 % CI: 72 %–88 %), and were similar to the rates in English-speaking (80.0 %, 95 % CI: 73 %–86 %) and Spanish-speaking (87.6 %, 95 % CI: 82 %–91 %) women. PN increased screening rates in both younger and older refugee women.

CONCLUSION

Linguistically and culturally tailored PN decreased disparities over time in breast cancer screening among female refugees from Somalia, the Middle East and Bosnia.

KEY WORDS: breast cancer screening, patient navigation, vulnerable populations, disparities

INTRODUCTION

Despite evidence that reductions in breast cancer morbidity and mortality can be achieved through early detection and treatment,1,2 patients continue to present with advanced disease without prior screening.3,4 This is particularly true for refugees and recent immigrants, patients with limited English proficiency, patients with low income, and racial and ethnic minorities.5–9

Over 56,000 refugees were permanently resettled to the United States in 2011.10 Many suffer from posttraumatic stress disorder caused by events leading to forced emigration, making these patients among the most vulnerable in our society. While precise data about preventive cancer care among refugees is very limited, they are more likely than non-refugees to have never had a mammogram or to have delayed screening.11

The 2000 National Health Interview Survey revealed that women who immigrated to the United States within the last 10 years were less likely to have had a mammogram within the last 2 years than non-immigrants.12 This is largely due to a lack of knowledge about preventive health care and mammography screening,13–16 fear about the procedure, or racial discrimination.17,18 Arab immigrant women are more likely to avoid cancer screenings because of embarrassment and fear of cancer diagnosis,19 and therefore have lower mammography rates than other groups.13 These disparities, seen in many ethnic minority groups in the United States, result in increased breast cancer risk, presentation at a later stage of disease, and increased mortality and morbidity following diagnosis.5

Over the last two decades, there has been major immigration of Bosnian, Somali and Arabic speaking women from Africa and the Middle East.20 Health centers located in gateway communities are challenged to identify health disparities and intervene to improve preventive care in these refugees. Examination of preventive cancer care among the refugees seen at the Massachusetts General Hospital Chelsea HealthCare Center (MGH Chelsea) revealed that women in these groups had lower mammography rates than English-speaking or Spanish-speaking women at this health center.

Patient navigation (PN), a novel health care role introduced in Harlem, New York in the 1990’s, has been shown to improve cancer screening in disadvantaged populations.21–25 We developed and implemented a linguistically and culturally tailored breast cancer screening program using patient navigators to reach Bosnian, Somali and Arabic refugee women. An initial 1-year pilot demonstrated a positive impact on screening rates in the Bosnian women.26 This follow-up study evaluates the effect of the PN program on decreasing disparities in breast cancer screening in three populations of refugee women over a 3-year period.

METHODS

Setting

The study was performed at MGH Chelsea, an urban community health center (HC) affiliated with Massachusetts General Hospital. Located 2 miles north of Boston, the city of Chelsea has become home to refugees fleeing Somalia, Bosnia, and Iraq. These countries have been devastated by war and poverty, and their residents have had limited access to health care.27

The first PN program to address local disparities and improve breast care in Spanish-speaking patients was initiated at MGH Chelsea in 2001.28 Between 2008 and 2011, Massachusetts supported a PN program to promote prevention (including mammography) in low income women aged 40–65 years. Additionally, every woman who has ever had a mammogram at MGH Chelsea receives a yearly reminder letter from the radiology department. While all women were eligible for these existing programs, refugee patients’ screening rates remained significantly lower than English-speaking and Spanish-speaking women at the same HC.

Participants

Women were eligible for the refugee PN program if they were 40–74 years of age, self identified as speaking Serbo-Croatian, Somali, or Arabic, and received primary care at MGH Chelsea. Patients were excluded if they had bilateral mastectomy. Comparison groups consisted of English-speaking and Spanish-speaking women between 40 and 74 years of age who were receiving care at MGH Chelsea during the same period. All study activities were approved by the MGH Institutional Review Board.

Intervention

We developed a refugee PN breast care training curriculum (six 2-hour sessions) for community women and HC staff from the three targeted populations. Navigators learned how to educate patients about breast health, explore patient’s barriers to screening, provide logistical and emotional support to overcome those barriers, and how to help women obtain screening and diagnostic mammograms when needed. Three PNs were hired, including a woman from the Bosnian community who worked half time (0.5 FTE) and two outreach workers already working at the HC for 2–3 h per week (0.05–0.08 FTE) to serve as PNs for the Somali and Arabic speaking women. PNs had no prior medical training and their educational backgrounds ranged from high school to college graduates. Due to turnover among the PNs, new hires received the 12 h of training on an individual basis. Training material was revised after November, 2009 to reflect updated USPSTF guidelines.29 Culturally and linguistically tailored educational handouts for patients were developed using Susan G. Komen material as a template. PNs and patients from the community worked with medical interpreters to adapt materials to the culture and educational level of patients from targeted communities.

The refugee PN program formally started in April, 2009. Initially, patients were mailed a letter that introduced the program and included our culturally and linguistically appropriate educational materials about breast cancer screening. Approximately 1 week later, the PN from the same culture and language background contacted the patient by phone or in person at MGH Chelsea. Navigators educated patients about preventive care and the importance of routine mammograms, and explored each patient’s barriers to screening. Tailoring their interventions to each individual patient’s needs, the PNs helped to schedule appointments, make reminder calls, arrange transportation, resolve insurance issues and even accompany patients to their appointments if they were afraid or felt they were unable to complete the mammogram appointment on their own.26

At the beginning of each year, an updated list of refugee women who were eligible for the program was generated electronically and PNs contacted patients who had not had a mammogram in the prior year. The greatest effort was needed during the first screening cycle, and often required multiple phone calls, an in-person meeting or home visit. Time spent with each patient varied from 1 to 8 h. In subsequent years, many previously “navigated” women only needed scheduling and reminder phone calls.

To increase awareness about breast cancer in the communities where our refugee patients reside, we held several outreach sessions at local churches and mosques during the years of the navigation program.

Study Design and Outcomes

We performed a retrospective evaluation of an implemented program. Both patient characteristics and mammography data were obtained from an electronic central data repository at Partners HealthCare.30 Dates of completion of mammograms were obtained from electronic reports and billing data. The primary study outcome was the proportion of patients who completed a mammogram during the prior 2 years. The outcome was assessed over the 4-year follow-up period, including the year prior to the implementation of the PN program (2008) and 3 years after implementation (2009–2011). Additionally, we examined the primary outcome stratified by patient age (40–49 and 50–74 years) and among women who were patients at the MGH Chelsea during all four study years.

Statistical Analyses

We compared patient characteristics between the groups using two-sample t-tests or Chi-square tests, as appropriate. For each calendar year, we compared the proportion of patients completing mammography screening during the prior 2 years among refugee women compared to English-speaking and Spanish-speaking patients cared for at MGH Chelsea during the same time period. We used logistic regression with general estimating equations techniques to account for clustering by primary care physician (PROC GENMOD, SAS version 9.2, SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). To control for differences in patient characteristics among groups, patient age, race, insurance status, and number of clinic visits were included in the models as covariates.

RESULTS

Over the 4-year period (2008–2011), there were 188 refugee women eligible for breast cancer screening. Each year, new refugees would arrive and were enrolled in the program, while some moved away and were removed from the contact list. Overall, 110 women were patients at the HC during all 4 years of the study period; 50 were newly arrived refugees who contributed to at least 1 year’s screening rate, and 28 left the network. In any given year, there were, on average, 151 patients followed by PNs. Among 188 women in the program, 36 (19 %) were Somali-speaking, 48 (26 %) were Arabic-speaking, and 104 (55 %) were Serbo—Croatian-speaking (Bosnian). Over the same period, there were 2,072 English-speaking and 2,014 Spanish-speaking women eligible for breast cancer screening at the same HC. The proportion that contributed data in all 4 years was similar to the refugee patients. The average age among all women at baseline (in 2008 or on their initial presentation to the HC) was 54.4 years, and 75.4 % were connected to a specific HC primary care provider (Table 1). In the aggregate, refugee women were younger than English-speaking women, were more often on Medicaid, and were less likely to be on Medicare than both English-speaking and Spanish-speaking women. Refugees also had significantly different racial distributions than English-speaking and Spanish-speaking women.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic Characteristics of Participants by Study Group

| Patient characteristics, N (%) | Refugees (n = 188) | English (n = 2,072 ) | P value* | Spanish (n = 2,014 ) | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient–physician connectedness | 0.98 | 0.64 | |||

| Physician-connected | 143 (76.1 %) | 1,578 (76.2 %) | 1,501 (74.5 %) | ||

| Practice-connected | 45 (23.9 %) | 494 (23.8 %) | 513 (25.5 %) | ||

| Age, mean (SD) | 52.8 (9.0) | 55.8 (10.0) | < 0.001 | 53.1 (9.5) | 0.64 |

| Race | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||

| Asian | 2 (1.1 %) | 40 (1.9 %) | 1 (0.1 %) | ||

| Black | 36 (19.2 %) | 221 (10.7 %) | 0 | ||

| Hispanic | 0 | 395 (19.1 %) | 2,004 (99.5 %) | ||

| Other/unknown | 12 (6.4 %) | 32 (1.5 %) | 2 (0.1 %) | ||

| White | 138 (73.4 %) | 1,384 (66.8 %) | 7 (0.4 %) | ||

| Insurance status | < 0.001 | 0.02 | |||

| Commercial | 101 (53.7 %) | 1,165 (56.2 %) | 1,094 (54.3 %) | ||

| Medicaid | 65 (34.6 %) | 291 (14.0 %) | 519 (25.7 %) | ||

| Medicare | 15 (8.0 %) | 537 (25.9 %) | 263 (13.1 %) | ||

| Free/self | 7 (3.7 %) | 79 (3.8 %) | 138 (6.9 %) | ||

| Number of clinic visits over 3 years | 9.1 (7.2) | 9.0 (7.2) | 0.87 | 9.3 (6.1) | 0.74 |

*P values comparing each group to refugees

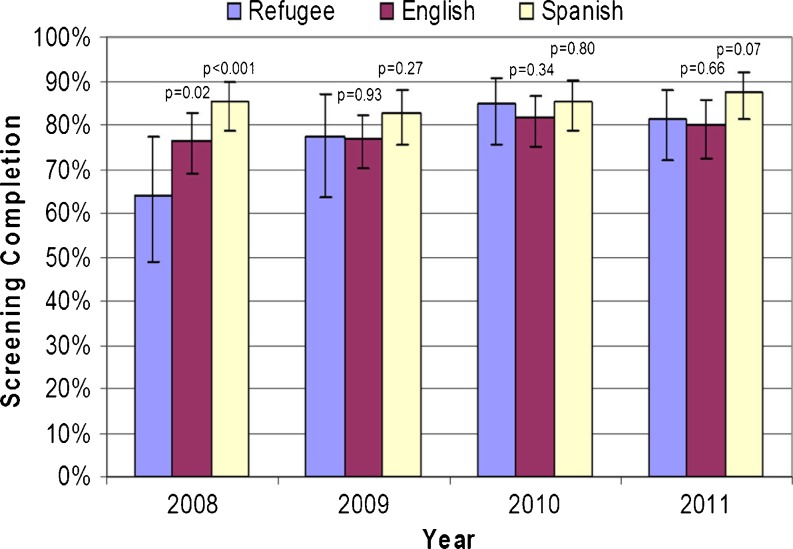

Unadjusted and adjusted mammography screening rates in refugee and comparison groups over the study period were similar, and therefore we only present adjusted data. In the year prior to implementation of the PN program (2008), adjusted mammography screening rates were significantly lower among refugee women (64.1 %, 95 % CI: 49 %–77 %) compared with English-speaking (76.5 %, 95 % CI: 69 %–83 %, p = 0.02) and Spanish-speaking (85.2 %, 95 % CI: 79 %–90 %, p < 0.001) women (Fig. 1). At the end of 2009, after the implementation of the PN program, screening rates increased among refugee women (77.3 %, 95 % CI: 64 %–87 %) and were similar to screening rates among English-speaking (76.8 %, 95 % CI: 70 %–82 %, p = 0.93) and Spanish-speaking (82.8 %, 95 % CI: 76 %–88 %, p = 0.27) women. At the end of 2010, screening rates among refugee women (84.7 %, 95 % CI: 76 %–91 %) were not significantly different from the rates in English-speaking (81.8 %, 95 % CI: 75 %–87 %, p = 0.34) or Spanish-speaking (85.5 %, 95 % CI: 79 %–90 %, p = 0.80) women. At the end of 2011, screening rates in refugee women were 81.2 %, (95 % CI: 72 %–88 %), which was statistically similar to screening rates in English-speaking (80.0 %%, 95 % CI: 73 %–86 %, p = 0.66) and Spanish-speaking (87.6 %, 95 % CI: 82 %–92 %, p = 0.07) women.

Figure 1.

Adjusted mammography screening completion rates within the prior 2 years, p values, and 95 % confidence intervals in the refugee group compared to English-speaking and Spanish-speaking groups over a 4-year period.

Stratifying results by patient age demonstrated that mammography rates increased over time among both younger (40–49 years) and older (≥ 50 years) refugee women. However, the greatest disparity prior to the implementation of the PN program and the largest effect of the PN program was among women aged 40–49 years. In 2008, adjusted screening rates among refugee women aged 40–49 years were 53.2 % (95 %CI: 40 %–66 %) compared to 73.5 % (95 % CI: 64 %–82 %, p < 0.001) among English-speaking and 85.4 % (95 % CI: 78 %–90 %, p < 0.001) among Spanish-speaking women (Table 2). By 2011, rates among refugee women were 86.7 % (95 % CI: 70 %–95 %) and were similar to the rates among English-speaking (78.4 %, 95 % CI: 67 %–87 %, p = 0.15) and Spanish-speaking (87.2 %, 95 % CI: 78 %–93 %, p = 0.92) women. Among women who were patients at the HC in all 4 years (n = 110), mammography screening rates were slightly higher for all groups before and after the start of the PN program (data not shown). However, the change in screening rates over time was similar to that seen among all eligible patients in each year.

Table 2.

Adjusted Breast Cancer Screening Rates Among Eligible Patients in Each Study Year Stratified by Age Group

| Women < 50 years | Women ≥ 50 years | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | Refugee | 53.2 % (40.0–65.9) | 73.8 % (49.4–88.7) |

| English | 73.5 % (63.6–81.4) | 79.7 % (70.0–86.7) | |

| Spanish | 85.4 % (78.1–90.5) | 81.8 % (69.5–90.0) | |

| 2009 | Refugee | 74.6 % (59.4–85.8) | 80.5 % (62.2–91.3) |

| English | 75.9 % (66.9–82.8) | 77.5 % (68.6–84.2) | |

| Spanish | 81.0 % (71.4–87.9) | 85.3 % (76.6–91.0) | |

| 2010 | Refugee | 86.4 % (72.5–93.9) | 84.6 % (74.2–91.1) |

| English | 80.7 % (70.8–87.4) | 83.5 % (75.9–88.7) | |

| Spanish | 84.9 % (74.1–91.5) | 85.5 % (77.7–90.8) | |

| 2011 | Refugee | 86.7 % (70.3–94.7) | 76.8 % (66.1–84.9) |

| English | 78.4 % (66.5–86.5) | 79.0 % (70.2–85.8) | |

| Spanish | 87.2 % (77.9–92.7) | 86.4 % (79.7–91.1) |

Models adjusted for age, clinic visits, race, insurance, linkage status and clustering by primary care physician

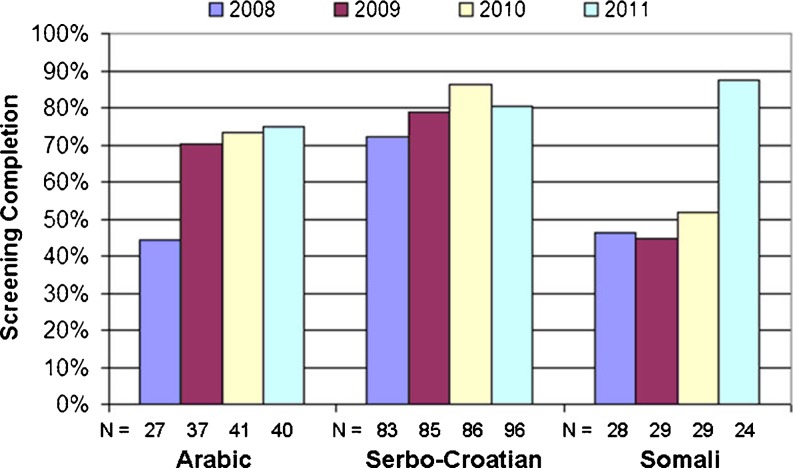

Breast cancer screening rates increased in all three groups of refugee women over the 4-year period (Fig. 2). Unadjusted mammography screening rates in Arabic-speaking women increased from 44.4 % before implementation of the PN program in 2008 to 75.0 % in 2011. Similarly, the mammography screening rates increased from 46.4 % in 2008 to 87.5 % in 2011 among Somali-speaking refugees, and from 72.3 % in 2008 to 80.2 % in 2011 among Serbo–Croatian-speaking refugees.

Figure 2.

Unadjusted mammography screening completion rates within the prior 2 years in Arabic, Serbo-Croatian and Somali refugee groups over a 4-year period.

DISCUSSION

We evaluated the impact of a culturally-tailored PN program for refugee women to decrease disparities in breast cancer screening. Over the first 3 years of this program, mammography rates improved in refugee women from Somalia, the Middle East and Bosnia, and we significantly decreased disparities in screening rates between these refugees and English-speaking and Spanish-speaking women receiving care at the same health center.

There is a great need to address health disparities in vulnerable populations.24 Several studies have shown that patient navigation can improve mammography rates in vulnerable populations.22–24,31 However, we are not aware of prior studies assessing the impact of patient navigation on decreasing disparities for breast cancer screening in refugee women. Although the refugee women in our study had already been patients at a health center with programs designed to improve breast cancer care in low income, underserved populations, refugee’s breast cancer screening rates were significantly lower than other low income women at the health center. In designing this program for refugee women, we focused on hiring PNs from the same linguistic and cultural backgrounds as our refugees. Sharing similar experiences of war and relocation may have helped PNs develop trusting relationships with patients and enabled patients to overcome fears and perceived barriers to screening.

Our program seemed to have a larger impact on younger refugee women, but this may have reflected higher baseline screening rates in refugee women over 50. Most of these older women were Bosnian refugees from the former Yugoslavia who had arrived in the United States in the early 1990s. Many had been followed by their health center physicians for a long time, and may have been convinced to accept their recommendations regarding breast cancer screening. This may, in turn, have resulted in higher screening rates in older refugee women in 2008 prior to the start of the refugee PN program.

Mammography screening rates increased after the start of the PN program for all women, both younger and older. However, in older women mammography screening rates decreased between 2010 and 2011 (Table 2). This decrease is reflected by lower screening rates in Bosnian refugees in the last year of the program (Fig. 2). At the end of the second year of the program, there was no Serbo-Croatian (Bosnian) speaking PN for a 5-month period. This likely decreased the impact of the program and highlights the ongoing challenge of retaining skilled bilingual PNs in health center positions.

In contrast, we observed a large increase in screening rates in Somali women in the last year of the program. For this group, the hiring and training of a new Somali PN midway through the program may have delayed building the trusting relationships needed to provide more intense and prolonged education that facilitate screening acceptance. Somali speaking refugees are mostly Bantu, poor, illiterate in their own language, and with little or no prior knowledge of breast cancer. Future studies should explore barriers to preventive care and breast cancer screening faced by these three groups of very culturally and educationally different refugee women,13,32 to help provide better health care services for these vulnerable populations.

The refugee PN program received foundation support of $30,000 for navigator salaries and $9,000 for patient expenses, educational material, and evaluation and dissemination on a yearly basis. The training and supervision of PNs were supported by hospital funds. Program expenses were greatest in its first year. Less intense outreach in subsequent years for prior participants enabled navigators to focus on a smaller number of new patients, as well as women who had declined screening in prior years. With this increased efficiency in later years, the refugee PN program was able to expand to other practices in our network. Our three part-time PNs now navigate Somali, Serbo-Croatian and Arabic speaking women in all 16 network practices (not analyzed in this study). This programmatic expansion made it difficult to estimate ongoing costs for this study. To assess whether these programs should be reimbursed as part of the routine care of vulnerable populations, next steps should focus on what components of these programs worked best and their cost effectiveness.

Several important limitations warrant consideration. Since this was a retrospective evaluation of a previously implemented program, it is not possible to state that the outcomes observed over time were solely due to the PN program. Our results, from an urban community HC affiliated with an academic medical center, may not be generalizable to other clinical settings. If non-refugee HC patients were more likely to have had mammograms performed outside of our network than refugee women, our comparisons may overestimate the decrease in disparities observed. Since almost all Somali, Arabic, or Serbo-Croatian (Bosnian) speaking refugee women in our primary care network were seen at the MGH Chelsea, we chose English-speaking and Spanish-speaking women at the same HC as our comparators to assess changes in screening over time. These two groups of women received care at the same HC and represented a population with similar socioeconomic status and access to practice-based breast cancer screening initiatives during the study period. Finally, since we targeted women from three very culturally and educationally different communities,13,32 it was difficult to distinguish which aspects of the PN program had the most impact.

In conclusion, a culturally tailored, language-concordant navigator program designed to identify and overcome barriers to breast cancer screening improved mammography rates in refugee women, and over time decreased observed disparities in care.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patient navigators and the Community Health Team at the MGH Chelsea HealthCare Center for their work on the program.

This program was funded by Susan G. Komen for Cure Massachusetts Affiliate Foundation. Drs. Percac-Lima and Atlas are supported in part from a grant from the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (R18 HS018161).

The study was presented at the New England Meeting of the Society of General Medicine in Portland ME on March 23 2012, and at the Annual Meeting of the Society of General Medicine in Orlando, FL on May 10 2012.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Deavenport A, Modeste N, Marshak HH, et al. Closing the gap in mammogram screening: an experimental intervention among low-income Hispanic women in community health clinics. Health Educ Behav. 2011;38(5):452–461. doi: 10.1177/1090198110375037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson HD, Tyne K, Naik A, et al. Screening for breast cancer: an update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(10):727–737. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-10-200911170-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cho YI, Johnson TP, Barrett RE, et al. Neighborhood changes in concentrated immigration and late stage breast cancer diagnosis. J Immigr Minor Health. 2010;13(1):9–14. doi: 10.1007/s10903-010-9339-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dai D. Black residential segregation, disparities in spatial access to health care facilities, and late-stage breast cancer diagnosis in metropolitan Detroit. Health Place. 2010;16(5):1038–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradley CJ, Given CW, Roberts C. Disparities in cancer diagnosis and survival. Cancer. 2001;91(1):178–188. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010101)91:1<178::AID-CNCR23>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flores G. Language barriers to health care in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(3):229–231. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goel MS, Wee CC, McCarthy EP, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in cancer screening: the importance of foreign birth as a barrier to care. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(12):1028–1035. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2003.20807.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kandula NR, Wen M, Jacobs EA, et al. Low rates of colorectal, cervical, and breast cancer screening in Asian Americans compared with non-Hispanic whites: cultural influences or access to care? Cancer. 2006;107(1):184–192. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Porter P. “Westernizing” women’s risks? Breast cancer in lower-income countries. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(3):213–216. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0708307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin DC. Refugees and Asylees: 2011. http://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/statistics/publications/ois_rfa_fr_2011.pdf. Accessed April 07, 2013.

- 11.Barnes DM, Harrison CL. Refugee women’s reproductive health in early resettlement. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2004;33(6):723–728. doi: 10.1177/0884217504270668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dohan D, Levintova M. Barriers beyond words: cancer, culture, and translation in a community of Russian speakers. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(Suppl 2):300–305. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0325-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carroll J, Epstein R, Fiscella K, et al. Knowledge and beliefs about health promotion and preventive health care among somali women in the United States. Health Care Women Int. 2007;28(4):360–380. doi: 10.1080/07399330601179935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawar LN. Jordanian and Palestinian immigrant women’s knowledge, affect, cultural attitudes, health habits, and participation in breast cancer screening. Health Care Women Int. 2009;30(9):768–782. doi: 10.1080/07399330903066111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kobetz E, Menard J, Barton B, et al. Barriers to breast cancer screening among Haitian immigrant women in Little Haiti, Miami. J Immigr Minor Health. 2010;12(4):520–526. doi: 10.1007/s10903-010-9316-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koh C, Nelson JM, Cook PF. Evaluation of a patient navigation program. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15(1):41–48. doi: 10.1188/11.CJON.41-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellis BH, MacDonald HZ, Lincoln AK, et al. Mental health of Somali adolescent refugees: the role of trauma, stress, and perceived discrimination. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76(2):184–193. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wissink L, Jones-Webb R, DuBois D, et al. Improving health care provision to Somali refugee women. Minn Med. 2005;88(2):36–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah SM, Ayash C, Pharaon NA, et al. Arab American immigrants in New York: health care and cancer knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs. J Immigr Minor Health. 2008;10(5):429–436. doi: 10.1007/s10903-007-9106-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Migration Information Source. http://www.migrationinformation.org/index.cfm. Accessed April 7, 2013.

- 21.Freeman HP, Muth BJ, Kerner JF. Expanding access to cancer screening and clinical follow-up among the medically underserved. Cancer Pract. 1995;3(1):19–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paskett ED, Harrop JP, Wells KJ. Patient navigation: an update on the state of the science. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(4):237–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phillips CE, Rothstein JD, Beaver K, et al. Patient navigation to increase mammography screening among inner city women. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;26(2):123–129. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1527-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robinson-White S, Conroy B, Slavish KH, et al. Patient navigation in breast cancer: a systematic review. Cancer Nurs. 2010;33(2):127–140. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181c40401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wells KJ, Battaglia TA, Dudley DJ, et al. Patient navigation: state of the art or is it science? Cancer. 2008;113(8):1999–2010. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Percac-Lima S, Milosavljevic B, Oo SA, et al. Patient navigation to improve breast cancer screening in Bosnian refugees and immigrants. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(4):727–730. doi: 10.1007/s10903-011-9539-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Refugee Arrivals to Massachusetts by Country of Origin. http://www.mass.gov/eohhs/gov/departments/dph/programs/id/public-health-cdc-refugee-arrivals.html Accessed April 07, 2013.

- 28.Donelan K, Mailhot JR, Dutwin D, et al. Patient perspectives of clinical care and patient navigation in follow-up of abnormal mammography. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(2):116–122. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1436-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.U. S. Preventive Services Task Force Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(10):716–726. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-10-200911170-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murphy SN, Chueh HC. A security architecture for query tools used to access large biomedical databases. Proc AMIA Symp. 2002;552–6. PMC2244204. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Dietrich AJ, Tobin JN, Cassells A, et al. Telephone care management to improve cancer screening among low-income women: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(8):563–571. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-8-200604180-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saadi A, Bond B, Percac-Lima S. Perspectives on preventive health care and barriers to breast cancer screening among Iraqi women refugees. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(4):633–639. doi: 10.1007/s10903-011-9520-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]