ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Recent data suggest that aspirin may be effective for reducing cancer mortality.

OBJECTIVE

To examine whether including a cancer mortality-reducing effect influences which men would benefit from aspirin for primary prevention.

DESIGN

We modified our existing Markov model that examines the effects of aspirin among middle-aged men with no previous history of cardiovascular disease or diabetes. For our base case scenario of 45-year-old men, we examined costs and life-years for men taking aspirin for 10 years compared with men who were not taking aspirin over those 10 years; after 10 years, we equalized treatment and followed the cohort until death. We compared our results depending on whether or not we included a 22 % relative reduction in cancer mortality, based on a recent meta-analysis. We discounted costs and benefits at 3 % and employed a third party payer perspective.

MAIN MEASURE

Cost per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained.

KEY RESULTS

When no effect on cancer mortality was included, aspirin had a cost per QALY gained of $22,492 at 5 % 10-year coronary heart disease (CHD) risk; at 2.5 % risk or below, no treatment was favored. When we included a reduction in cancer mortality, aspirin became cost-effective for men at 2.5 % risk as well (cost per QALY, $43,342). Results were somewhat sensitive to utility of taking aspirin daily; risk of death after myocardial infarction; and effects of aspirin on stroke, myocardial infarction, and sudden death. However, aspirin remained cost-saving or cost-effective (< $50,000 per QALY) in probabilistic analyses (59 % with no cancer effect included; 96 % with cancer effect) for men at 5 % risk.

CONCLUSIONS

Including an effect of aspirin on cancer mortality influences the threshold for prescribing aspirin for primary prevention in men. If such an effect is real, many middle-aged men at low cardiovascular risk would become candidates for regular aspirin use.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2465-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: aspirin, cancer mortality, coronary heart disease, guideline-based intervention, primary prevention

BACKGROUND

Aspirin has been shown to be effective in preventing myocardial infarction in men.1,2 However, it also increases the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, even at low doses.1,3,4 The effect on stroke is mixed: Aspirin may slightly reduce the risk of ischemic strokes, but it also increases the less frequent hemorrhagic type.1 Several systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and evidence-based clinical guidelines have quantified these effects and offered opinions about the utility of aspirin for primary prevention based on counts of the beneficial and detrimental events.1,2,5–9 The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends aspirin for primary prevention in men for “when the potential benefit of a reduction in myocardial infarctions outweighs the potential harm of an increase in gastrointestinal hemorrhage.” 5

Cost-effectiveness and cost-utility analysis offer a means of synthesizing information about the beneficial and harmful effects of aspirin and can help inform decision-making about who should or should not be offered aspirin for primary prevention. Our previous analyses have found that aspirin appears to be more effective and less costly than no therapy in middle-aged men who are at 5 % or greater 10-year risk for coronary heart disease (CHD).10,11 Greving and colleagues found that aspirin was cost-effective in Dutch men at 10 % or greater risk.12 In these analyses, the beneficial effects of prevention of non-fatal myocardial infarction outweighed the downsides of increased gastrointestinal bleeding and increased strokes.

Recently, Rothwell and colleagues published a systematic review and meta-analysis suggesting that, in addition to its cardiovascular benefits, long-term daily aspirin use may be effective in prevention of cancer-related mortality.13 This conclusion is also supported by findings from individual trials in high-risk patients and a number of basic and observational studies.14 If aspirin is effective in preventing cancer mortality in addition to its cardiovascular benefits, the threshold for offering aspirin may be lowered, both in terms of age of initiation and risk level at which the benefits would exceed the downsides. To test this hypothesis, we modified our pre-existing model to include a cancer mortality reduction from aspirin and examined how such an effect changes the cost-effectiveness of aspirin for primary prevention in middle-aged men at low to moderate CHD risk.

METHODS

We developed an updated Markov model, programmed in Microsoft Excel, based on our previous modeling work.10,11,15 Because of significant differences in the quantity and strength of the evidence for aspirin effectiveness by sex and possibly by presence or absence of diabetes, we limited the current analysis to non-diabetic men. In the model, men begin in the healthy state and then transition through the model states in 12-month cycles (on-line Appendix Figure O-1). In each cycle, men can remain in the healthy state; progress to have an initial cardiovascular non-fatal event such as angina, myocardial infarction, or stroke; have a gastrointestinal bleed; or die from cancer or a non-cancer cause.

Men who have non-fatal cardiovascular events (angina, myocardial infarction, or stroke) are assumed to stay in a sub-acute state for the remainder of that cycle, then enter a post-event health state where they receive optimal secondary prevention. The model does not simulate in-depth the additional course for men after a primary, non-fatal event. Instead, it assigns them an increased risk of mortality, increased costs, and decreased utilities, using data on the average experience of men after an initial event.16,17

Men who have a gastrointestinal bleed sustain an increased risk of death during that year and discontinue aspirin. They then enter a post-event health state where they progress through the model as healthy men, except with a higher risk for subsequent gastrointestinal bleeding.3

The Markov model is used to estimate events, costs, life-years, and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs). Sources for the model parameters are shown in Table 1. We used a third-party payer perspective, and costs and outcomes were discounted at an annual rate of 3 %.

Table 1.

Model Parameters, Values, and Plausible Ranges

| Parameter | Base-Case Value (Range/95 % CI) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Effect of Aspirin | ||

| Relative risk angina | 1.00 (95 % CI: 0.80, 1.20) | Assumption |

| Relative risk stroke | 1.13 (95 % CI: 0.91, 1.24) | 2 |

| Relative risk myocardial infarction | 0.70 (95 % CI: 0.62, 0.79) | 8 |

| Relative risk CHD death | 0.95 (95 % CI: 0.82, 1.10) | 1 |

| Relative risk GI bleed (no history of GI bleed) | 2.00 (95 % CI: 1.70, 2.20) | 3 |

| Relative risk GI bleed (with history of GI bleed) | 10.00 (range: 5.00, 15.00) | 3 |

| Proportion of strokes that are fatal | 0.1440 (range: 0.0718, 0.2155) | 1 |

| Proportion of GI bleeds that are fatal | 0.0100 (range: 0.0002, 0.0500) | Expert opinion; 1,12,30,31 |

| Relative risk of cancer mortality with aspirin | 0.78 (95 % CI: 0.70, 0.87) | 13 |

| Increase in risk of mortality after myocardial infarction | 3.7 (95 % CI: 3.0, 4.7) | 16 |

| Increase in risk of mortality after angina | 3.0 (95 % CI: 2.1, 4.2) | 16 |

| Increase in risk of mortality after stroke | 2.3 (95 % CI: 1.0, 4.6) | 17 |

| Reduction of death due to aspirin therapy after a CV event | 0.85 (95 % CI: 0.80, 0.90) | 24 |

| Reduction in death after CV event due to optimal therapy | 0.670 (range: 0.576, 0.774) | 24, 25 |

| Cost Data (Annual) † | ||

| Aspirin | $9.12 | 32 |

| Outpatient physician visit | $70.46 | 33 |

| Health-State Costs (Annual) † | ||

| Healthy | $70.46 | 33 |

| GI bleed | $16,868 | 28, 33–35 |

| Post GI bleed | $70.46 | 33 |

| Angina | $15,657 | 28, 33–36 |

| Post angina | $6,832 | 28, 36 |

| Stroke | $51,175 | 28, 33–35, 37, 38 |

| Post stroke | $13,628 | 28, 34, 35, 37, 38 |

| Myocardial infarction | $39,000 | 28, 33–35, 37 |

| Post myocardial infarction | $4,750 | 28, 39 |

| Other Healthcare Costs (Annual)† | ||

| Age 35–44 | $4,247 | 26, 28 |

| Age 45–54 | $6,239 | 26, 28 |

| Age 55–64 | $8,747 | 26, 28 |

| Age 65–69 | $13,431 | 26, 28 |

| Age 70+ (one time cost) | $18,755 | 27, 28 |

| Utility Data | ||

| Healthy | 1.000* | Assumption |

| GI bleed | 0.940 (95 % CI: 0.880, 1.000) | 40 |

| Post GI bleed | 1.000 * | Assumption |

| Angina | 0.929 (95 % CI: 0.923, 1.000) | 41 |

| Post angina | 0.997 (95 % CI: 0.997, 1.000) | 41 |

| Stroke | 0.610 (95 % CI: 0.480, 0.830) | 40 |

| Post stroke | 0.830 (range: 0.420, 1.000)_ | 42 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0.870 (95 % CI: 0.820, 0.920) | 43 |

| Post myocardial infarction | 0.910 (95 % CI: 0.860, 0.960) | 43 |

| Utility of taking a pill | 0.999 * | Assumption |

CHD coronary heart disease; CI confidence interval; CV cardiovascular;GI gastrointestinal

*Not varied in sensitivity analyses

†All costs are varied by +/− 50 % in sensitivity analyses

Patient Population

In the base case analysis, we simulated men with a starting age of 45 years; no history of coronary heart disease (CHD) events, diabetes, or stroke; and a 5 % 10-year CHD risk. We also present results for different levels of 10-year CHD risk (from 2.5 % to 10 %) and a different starting age (55 years).

Comparators

Healthy men assigned to aspirin prevention received 81 mg of generic aspirin daily. Those assigned to “no aspirin” did not receive aspirin for primary prevention for 10 years. After 10 years, both cohorts received aspirin for primary prevention. For this analysis, we did not simulate use of other cardiovascular preventive strategies (smoking cessation, hypertension treatment, or statin use). We assumed 100 % adherence to simulate the effect of regular aspirin use.

Model Parameters

Baseline Event Rates

Baseline risks of initial CHD events (myocardial infarction, angina, and CHD death) and stroke were drawn from Framingham risk equations, using hypothetical scenarios of non-smoking, non-diabetic adults with different sets of risk factors.18 For the 5 % risk scenario, we assumed systolic blood pressure of 120 mmHg, total cholesterol of 170 mg/dl, and HDL cholesterol of 40 mg/dl. For sensitivity analyses, we varied these factors to attain overall 10-year CHD risk levels of 1.25 %, 2.5 %, 7.5 %, and 10 %. Assuming an exponential distribution, we translated 10-year CHD risks (myocardial infarction, CHD death, and angina) and stroke risks into annual, event-related transition probabilities. These probabilities were allowed to change annually to reflect increasing risk with increasing age over the time horizon of the analysis.

Age-dependent non-cardiovascular mortality rates were estimated from the National Vital Statistics life tables.19 Probabilities were adjusted as the cohort aged over the time horizon of the analysis. We estimated the proportion of deaths due to cancer by age from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) cancer statistics.20

We used estimates of gastrointestinal bleeding risk from an observational cohort study by Hernandez-Diaz et al.3 The baseline risk of gastrointestinal bleeding increases as members of the cohort age (45–54 years of age: 0.008; 55–74 years: 0.0024; 75–84 years: 0.0036). We assumed 1 % of gastrointestinal bleeds would be fatal, based on case series and prior aspirin trials.1,2,21,22

Aspirin Effects

The relative risk reductions (for CHD events and cancer mortality) and increases (for gastrointestinal bleeding and total stroke (including both ischemic and hemorrhagic events)) for aspirin were drawn from published meta-analyses and clinical trials and are presented in Table 1. We used sex-specific estimates when available. Based on the Rothwell meta-analysis, we assumed that aspirin therapy reduced the risk of cancer mortality by 22 % (or 0 % in parallel analyses excluding this putative effect), with the effect beginning 5 years after initiation of aspirin.13 We did not simulate the effect of aspirin on cancer incidence.23

Men who had a non-fatal cardiovascular event were at increased risk of mortality in all subsequent years.16,17 However, we also assumed they would receive optimal secondary prevention, which reduced their mortality by 33 %.24,25

Costs

As in our past analyses, we considered costs of outpatient physician visits, events, and medications. In this analysis, we also considered average annual costs of healthcare.26,27 Other healthcare costs are applied annually for all patients as long as they are alive, and increase with increasing age. When men reach the age of 70, they incur a one-time cost that represents the average non-CVD related healthcare costs for the remainder of the patient’s lifetime (Table 1).

Healthy men with or without a previous gastrointestinal bleed were assumed to incur one outpatient visit per year. Acute event health states (angina, myocardial infarction, stroke, and gastrointestinal bleed) include the cost of hospitalization for the respective event. Once a man had a CVD event, he was assumed to have four additional visits a year. We did not specifically examine the costs of cancer care or the effects of aspirin on these costs.

All costs are reported in 2012 US dollars and were inflated using the Medical Consumer Price Index when appropriate.28–39

Utilities

The utilities for each health state were drawn from the literature and are also shown in Table 1.40–43 In most cases, they were estimated using time trade-off techniques in the original studies. Where no data existed, we made estimates and examined a wide range of values in sensitivity analysis. In our base-case scenario, we estimated the disutility associated with taking aspirin each day at 0.999 (equivalent to losing 11 days of life with perfect health over the course of 30 years). This value represents decreased quality of life from non-major bleeding (nose bleeds, bruising), dyspepsia, and any hassle of taking a pill daily.

Outcomes

Our main outcome of interest was the cost per QALY gained for aspirin vs. no therapy. We first estimated cost per QALY assuming no effect of aspirin on cancer mortality; we then compared our results when the effect of aspirin on cancer mortality was included.

Sensitivity Analyses

To test the robustness of the model assumptions and specific parameters, we systematically examined the effect of changing key parameters in one-way sensitivity analyses. We also performed probabilistic sensitivity analysis (second-order Monte Carlo simulation). We assumed that the following parameter estimates followed a gamma distribution: all relative risk of events, increases in GI bleed, effects on mortality, health state costs, and drug costs. A beta distribution was assumed for health state utilities. We did not vary costs or the disutility of taking aspirin. Analyses were run 10,000 times in order to capture stability in the results for each relevant scenario. We developed scatter plots to represent uncertainty, and created cost-effectiveness acceptability curves.

RESULTS

Table 2 shows the effects of 10 years of aspirin therapy on clinical outcomes over 10 years, 20 years, and a full lifetime for a cohort of 10,000 45-year-old men in the base case scenario (5 % 10-year CHD risk). Aspirin use produced fewer non-fatal myocardial infarctions and fewer deaths, but more gastrointestinal bleeding and slightly more strokes. When the effect of aspirin on cancer mortality was included, the difference in total deaths at 20 years between aspirin and no aspirin was twice as large as compared with when no cancer mortality effect was assumed (28 vs. 14).

Table 2.

Events Over Various Time Horizons for a Cohort of 10,000 45-Year-Old Men with a 5 % 10-Year CHD Risk

| Event | 10 Years | 20 Years | Lifetime | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin | No Tx | Difference* | Aspirin | No Tx | Difference* | Aspirin | No Tx | Difference* | |

| Including Cancer’s Impact | |||||||||

| Angina | 266 | 266 | 0 | 496 | 494 | +2 | 770 | 766 | +4 |

| GI Bleed | 182 | 91 | +91 | 410 | 308 | +102 | 877 | 775 | +102 |

| MI | 120 | 171 | −51 | 278 | 332 | −54 | 634 | 685 | −51 |

| Stroke | 80 | 70 | +10 | 193 | 182 | +11 | 482 | 469 | +13 |

| Total Deaths | 766 | 783 | −17 | 2,361 | 2,389 | −28 | 10,000 | 10,000 | 0 |

| Deaths due to | |||||||||

| GI Bleed | 2 | 1 | +1 | 4 | 3 | +1 | 9 | 8 | +1 |

| Cancer | 120 | 138 | −18 | 417 | 436 | −19 | 1,666 | 1,679 | −13 |

| Other Causes | 644 | 644 | 0 | 1940 | 1,950 | −10 | 8,325 | 8,313 | +12 |

| Life Years | 9.6237 | 9.6194 | +0.0043 | 18.0707 | 18.0418 | +0.0289 | 27.9823 | 27.9025 | +0.0798 |

| QALYs | 8.4496 | 8.4537 | −0.0041 | 13.9674 | 13.9594 | +0.0080 | 18.2946 | 18.2686 | +0.0260 |

| Costs | $57,872 | $57,814 | +$58 | $112,751 | $112,592 | +$159 | $144,050 | $143,764 | +$286 |

| Excluding Cancer’s Impact | |||||||||

| Angina | 266 | 266 | 0 | 495 | 493 | +2 | 760 | 757 | +3 |

| GI Bleed | 182 | 91 | +91 | 408 | 307 | +101 | 858 | 757 | +101 |

| MI | 120 | 171 | −51 | 277 | 332 | −55 | 619 | 671 | −52 |

| Stroke | 80 | 70 | +10 | 193 | 182 | +11 | 469 | 457 | +12 |

| Total Deaths | 782 | 785 | −3 | 2,447 | 2,461 | −14 | 10,000 | 10,000 | 0 |

| Deaths due to | |||||||||

| GI Bleed | 2 | 1 | +1 | 4 | 3 | +1 | 9 | 8 | +1 |

| Cancer | 139 | 139 | 0 | 514 | 517 | −3 | 2,012 | 2,013 | −1 |

| Other Causes | 641 | 644 | −3 | 1,929 | 1,941 | −12 | 7,979 | 7,979 | 0 |

| Life Years | 9.6199 | 9.6190 | +0.0009 | 18.0158 | 18.0069 | +0.0089 | 27.5782 | 27.5364 | +0.0418 |

| QALYs | 8.4466 | 8.4534 | −0.0068 | 13.9325 | 13.9381 | −0.0056 | 18.1246 | 18.1199 | +0.0047 |

| Costs | $57,847 | $57,809 | +$38 | $112,375 | $112,341 | +$34 | $142,971 | $142,866 | +$105 |

CHD coronary heart disease; GI Bleed gastrointestinal bleed; MI myocardial infarction; No Tx no treatment; QALY quality-adjusted life year

*Difference represents aspirin minus No Tx

Aspirin produced more life-years than no therapy at each time point. However, the effect on QALYs depended on the time horizon modeled. At 10 years, the reduction in quality of life from taking aspirin (utility = 0.999) outweighed the net gains in life-years, even if the cancer benefit is included; at 20 years, aspirin produced a net gain in QALYs if cancer is included, but otherwise not. When a lifetime horizon was modeled, aspirin produced a net gain in QALYs whether or not the cancer benefit is included (Table 2).

Cost-utility results for the lifetime horizon are shown in Table 3 for scenarios varying the baseline CHD risk (a primary driver of aspirin effectiveness) and varying the disutility associated with aspirin. In the base case of 5 % risk and 0.999 utility for daily aspirin use, the cost-utility of aspirin was favorable with ($10,984 per QALY) or without ($22,492 per QALY) the inclusion of the cancer mortality effect, suggesting that aspirin can be recommended at 5 % risk or above. At 2.5 % risk and with no effect of aspirin on cancer mortality, aspirin was less effective and more costly than no treatment; however, with the inclusion of an effect of aspirin on cancer mortality, aspirin use was cost-effective ($43,342 per QALY) even at this low risk level. At even lower risk (1.25 % 10-year CHD risk), aspirin was not cost-effective with or without cancer mortality included.

Table 3.

Cost-Utility ($/QALY) with Aspirin: 45-Year-Old and 55-Year-Old Men at Different Levels of 10-Year CHD Risk

| 1.25 % Risk | 2.5 % Risk | 5.0 % Risk | 7.5 % Risk | 10.0 % Risk | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Utility of taking aspirin = 0.999, 45-year-old man | |||||

| Without effect on cancer mortality | Aspirin less effective and more costly | Aspirin less effective and more costly | $22,492 | Aspirin more effective and less costly | Aspirin more effective and less costly |

| With cancer mortality included | $165,422 | $43,342 | $10,984 | $700 | Aspirin more effective and less costly |

| Utility of taking aspirin = 1.0, 45-year-old man | |||||

| Without effect on cancer mortality | Aspirin less effective and more costly | $43,026 | $4,735 | Aspirin more effective and less costly | Aspirin more effective and less costly |

| With cancer mortality included | $22,706 | $15,447 | $6,529 | $526 | Aspirin more effective and less costly |

| Utility of taking aspirin = 0.999, 55-year-old man | |||||

| Without effect on cancer mortality | Aspirin less effective and more costly | $420,438 | $13,642 | $2,650 | |

| With cancer mortality included | $36,854 | $18,770 | $9,983 | $5,059 | |

| Utility of taking aspirin = 1.0, 55-year-old man | |||||

| Without effect on cancer mortality | Aspirin less effective and more costly | $30,549 | $8,367 | $2,029 | |

| With cancer mortality included | $23,488 | $14,006 | $8,120 | $4,331 | |

CHD coronary heart disease

If the utility of taking daily aspirin was set at 1.0 (no quality of life penalty modeled), aspirin was effective at all risk levels when cancer effects were included. Excluding other health care costs had a modest effect on cost-utility values but did not produce major changes in the populations for which aspirin is cost-effective (data not shown).

For 55-year old-men, aspirin was somewhat less cost-effective at each risk level than for 45-year-old men; in this case, including the cancer mortality reduction had important effects on whether aspirin was cost-effective for men at both 5 % and 2.5 % 10-year risk levels.

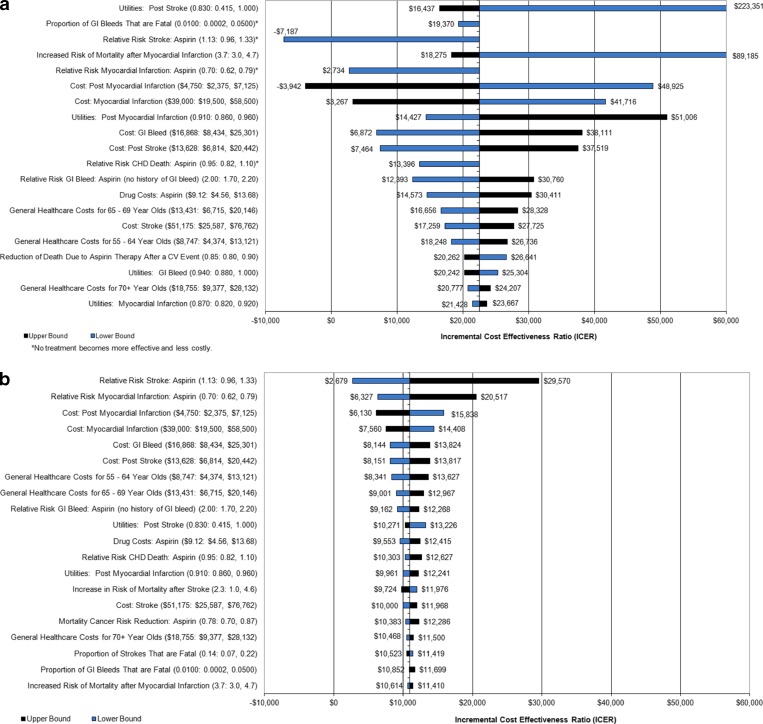

In one-way sensitivity analyses, the risk of stroke, gastrointestinal bleeding, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and CHD death with aspirin had moderate effects on cost-utility when no cancer effect was assumed (Fig. 1a). In the absence of a cancer effect, no treatment was favored at 5 % risk if the relative risk for CHD death with aspirin was over 1.02. When a risk reduction of 22 % for cancer mortality was assumed, the results are more robust (See Fig. 1b).

Figure 1.

Shows the results of a series of one-way sensitivity analyses (a with no cancer effect; b when a cancer effect is included) for men at 5 % 10 year risk. Parameters varied (and their ranges) are shown on the left; the bars represent the range of effects on the cost-utility of aspirin compared with no therapy, expressed as dollars per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained. CHD coronary heart disease; GI gastrointestinal; MI myocardial infarction.

If the relative risk of mortality with cancer is only 0.93, there is little difference in cost-effectiveness based on inclusion or exclusion of the cancer mortality effect (see on-line Appendix Table O-1) If the increased risk of mortality after CVD event was 2.0, no treatment is favored at 5 % risk (and 0.999 utility) in the absence of a cancer mortality effect. (See on-line Appendix Table O-2)

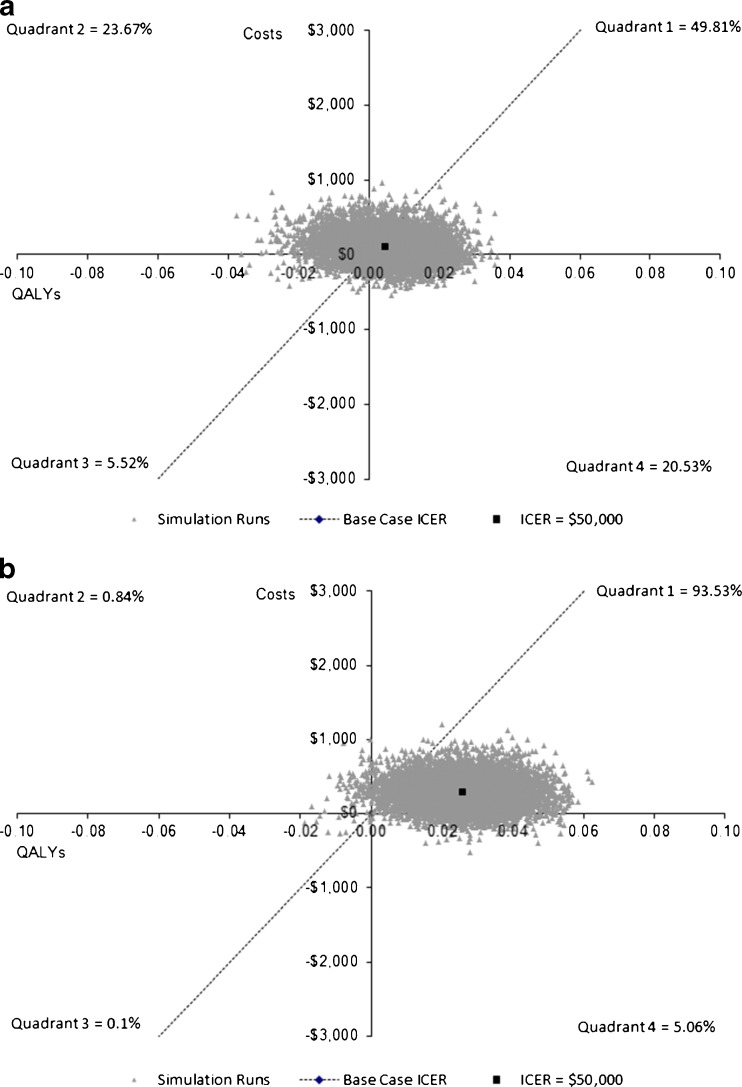

In probabilistic sensitivity analyses (Fig. 2), most results suggested aspirin to be cost-saving or cost-effective (less than $50,000 per life-year gained): this was true in the absence of a cancer effect for 59 % of scenarios and for 96 % of scenarios when a cancer effect was assumed. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves are shown in on-line Appendix Figure O-2.

Figure 2.

Shows the results of the probabilistic sensitivity analyses for men at 5 % 10 year CHD risk. Each grey triangle represents one simulation result. The dotted lines present the $50,000 per QALY gained threshold. a shows the results without a cancer mortality effect and b provides the results assuming aspirin reduces cancer mortality.

DISCUSSION

Daily aspirin is effective in preventing CHD events in men, primarily non-fatal myocardial infarction, but it also causes gastrointestinal bleeding and strokes.1,5 Rothwell and colleagues’ recent meta-analysis suggests that daily aspirin may also reduce the relative risk of cancer mortality by 22 %.13 We found that when this potential effect of aspirin on cancer mortality is included, aspirin becomes beneficial (and cost-effective) for a large group of middle-aged men at low 10-year CHD risk who otherwise might not receive net benefit from taking aspirin. In an analysis of 2009–2010 NHANES data, it was estimated that over 4 million men ages 40–49 have 10-year CHD risk between 2.5 % and 5 % (personal email communication, Hongyan Ning, August 2, 2012). Our findings are robust to several key assumptions in the model and suggest that guideline makers may need to reconsider their recommendations for primary prevention based on this cancer effect.5

Consistent with our past modeling analyses,10,11 we have identified a threshold for use of aspirin (in the absence of a cancer effect) that is below thresholds often advocated by others.1,2,5–9 Some of this variation arises from differences in estimates of aspirin’s beneficial or detrimental effects, but much of it reflects the weighing up of the long-term consequences that can only be examined through modeling.

Our results are also below the threshold identified by Greving and colleagues in their modeling work. They found aspirin to be cost-effective for 45-year-old men at moderately elevated risk (11 % 10-year cardiovascular risk); however, aspirin was not cost-effective at lower (5 %) risk and was less effective and more costly than no therapy at 2 % risk. Their model differed from ours in several respects: They used only a 10-year time horizon; assumed a much higher cost of aspirin (97 Euro per year, which included dispensing and prescription fees); modeled a higher (3 %) gastrointestinal bleeding case fatality rate; and did not include any cancer effect.12

We examined the effect of including or not including a disutility associated with daily aspirin use and found that it had important effects. There is little empirical or theoretical evidence to guide the value of this parameter, and hence we made a conservative choice for our base-case scenario. Further research is needed to better understand and measure this health state, as individuals may vary considerably in how they perceive it. As such, the decision about whether to take aspirin should be part of a shared decision making process.

We chose to use a lifetime time horizon to be sure to capture the full effects of prevention. Much of the cardiovascular benefit of aspirin comes from preventing non-fatal myocardial infarctions and the resultant reductions in subsequent mortality. However, to be conservative, we only allowed aspirin use to differ over the first 10 years, after which the two groups were equalized. Allowing differences in therapy over the full lifetime produces even larger benefits from aspirin compared with no therapy.

Although our study results were quite robust, several limitations must be noted. First, we did not model cancer incidence, or the effect of aspirin on cancer incidence. Further, our modeling of aspirin’s effects on cancer did not consider cost-savings from reduction in cancer treatment, including end-of-life care and chemotherapy. As such, we have likely underestimated the net impact of aspirin on cancer, assuming its true effects are similar to those reported in Rothwell and colleagues’ meta-analyses.13,23 Conversely, if the true effect of aspirin is much smaller than estimated by Rothwell and colleagues (as suggested by Seshasai and colleagues, who estimated a relative risk of 0.93),9 then there will be few or no effects on the threshold for net benefit from the mortality effect alone.

Our analysis assumed full adherence to aspirin, so as to answer the question of what the effect of regular use would be; however, adherence to preventive medicines is sub-optimal,29 and we have not included the costs of systematic adherence promotion, so its actual beneficial effects when offered to a population will be smaller (as will its adverse effects).

Our analysis is specific to middle-aged men at low CHD risk and not at high risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. We have too little data to determine whether it would hold for younger or elderly men, or for those with diabetes. We plan a subsequent analysis for women. In this paper, we did not model other potentially effective cardiovascular prevention strategies (e.g., statin use, smoking cessation therapies). Clinical decisions about aspirin use must take into account these other potential therapies, but even if all other therapies are utilized, many men will remain at risk levels for which aspirin use appears to be warranted.

In conclusion, our analysis suggests that aspirin appears beneficial for a large proportion of middle-aged men at low-moderate CHD risk, and that if its effects on cancer are real, this proportion would be even larger. Further research is required to increase our confidence in the true effects of aspirin on cancer. In the meantime, guideline makers and clinicians should discuss the potential benefits and downsides of aspirin in middle-aged men and consider its use in men who are not at high risk of adverse effects and not bothered by the need to take a pill daily.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 231 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Brenda Denzler and Penny Chumley for their assistance with editing and manuscript formatting.

Funding

Funding for this research was provided by Partnership for Prevention and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (R21 HL112256-01). Dr. Pignone was also supported through an Established Investigator Award from the National Cancer Institute (K05CA129166). Funders had no role in the design of the study, conduct of the study, analysis and interpretation of the data, or preparation and approval of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Earnshaw and Ms. McDade are employees of RTI Health Solutions, a contract research company that receives funds from pharmaceutical, biotechnology, and medical device/diagnostic manufacturers to perform outcomes research for cardiovascular disease and other conditions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antithrombotic Trialists’ (ATT) Collaboration Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2009;373(9678):1849–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60503-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berger JS, Roncaglioni MC, Avanzini F, Pangrazzi I, Tognoni G, Brown DL. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events in women and men: asex-specific meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2006;295(3):306–13. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.3.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hernandez-Diaz S, Garcia Rodriquez LA. Cardioprotective aspirin users and their excess risk of upper gastrointestinal complications. BMC Med. 2006;4:22. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-4-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Berardis G, Lucisano G, D’Ettorre A, et al. Association of aspirin use with major bleeding in patients with and without diabetes. JAMA. 2012;307(21):2286–94. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Preventive Services Task Force Aspirin for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(6):396–404. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-6-200903170-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berger JS, Lala A, Krantz MJ, Baker GS, Hiatt WR. Aspirin for the prevention of cardiovascular events in patients without clinical cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am Heart J. 2011;162(1):115–24.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raju N, Sobieraj-Teague M, Hirsh J, O’Donnell M, Eikelboom J. Effect of aspirin on mortality in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Am J Med. 2011;124(7):621–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanmuganathan PS, Ghahramani P, Jackson PR, Wallis EJ, Ramsay LE. Aspirin for primary prevention of coronary heart disease: safety and absolute benefit related to coronary risk derived from meta-analysis of randomised trials. Heart. 2001;85(3):265–271. doi: 10.1136/heart.85.3.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seshasai SR, Wijesuriya S, Sivakumaran R, et al. Effect of aspirin on vascular and nonvascular outcomes: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(3):209–16. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pignone M, Earnshaw S, Tice JA, Pletcher MJ. Aspirin, statins, or both drugs for the primary prevention of coronary heart disease events in men: a cost-utility analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(5):326–36. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-5-200603070-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Earnshaw SR, Scheiman J, Fendrick AM, McDade C, Pignone M. Cost-utility of aspirin and proton pump inhibitors for primary prevention. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(3):218–25. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greving JP, Buskens E, Koffijberg H, Algra A. Cost-effectiveness of aspirin treatment in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease events in subgroups based on age, gender, and varying cardiovascular risk. Circulation. 2008;117(22):2875–83. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.735340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rothwell PM, Fowkes FG, Belch JF, Ogawa H, Warlow CP, Meade TW. Effect of daily aspirin on long-term risk of death due to cancer: analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;377(9759):31–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62110-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan AT, Cook NR. Are we ready to recommend aspirin for cancer prevention? Lancet. 2012;379(9826):1569–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61654-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pignone M, Earnshaw S, Pletcher MJ, Tice JA. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in women: a cost-utility analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(3):290–5. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.3.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lampe FC, Whincup PH, Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG, Walker M, Ebrahim S. The natural history of prevalent ischaemic heart disease in middleaged men. Eur Heart J. 2000;21(131):1052–62. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1999.1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dennis MS, Burn JP, Sandercock PA, Bamford JM, Wade DT, Warlow CP. Long term survival after first-ever stroke: the Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project. Stroke. 1993;24(6):796–800. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.24.6.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson KM, Odell PM, Wilson PWF, Kannel WB. Cardiovascular disease risk profiles. Am Heart J. 1991;121(part 2):293–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(91)90861-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kung HC, Hoyert DL, Xu JQ, Murphy SL. Deaths: Final Data for 2005. National Vital Statistics Reports; vol 56 no 10. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. SEER*Stat Database: Mortality - All COD, Aggregated With State, Total U.S. (1969-2007), National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Cancer Statistics Branch, released April 2009. Available at: www.seer.cancer.gov. Accessed on September 8, 2011.

- 21.van Leerdam ME, Vreeburg EM, Rauws EA, et al. Acute upper GI bleeding: did anything change? Time trend analysis of incidence and outcome of acute upper GI bleeding between 1993/1994 and 2000. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(7):1494–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Incidence of and mortality from acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in the United Kingdom: Steering Committee and members of the National Audit of Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Haemorrhage. BMJ. 1995;311:222–226. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6999.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rothwell PM, Price JF, Fowkes FG, et al. Short-term effects of daily aspirin on cancer incidence, mortality, and non-vascular death: analysis of the time course of risks and benefits in 51 randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2012;379(9826):1602–12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61720-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He J, Whelton PK, Vu B, Klag MJ. Aspirin and risk of hemorrhagic stroke. JAMA. 1998;280(22):1930–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.22.1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LaRosa JC, He J, Vupputuri S. Effect of statins on risk of coronary disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 1999;282(24):2340–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.24.2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meara E, White C, Cutler DM. Trends in medical spending by age, 1963-2000. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;23(4):176–183. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.4.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lubitz J, Cai L, Kramarow E, Lentzner H. Health, life expectancy, and health care spending among the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(11):1048–1055. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa020614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.U.S. Department of Labor, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, US city average, not seasonally adjusted medical care. http://data.bls.gov/PDQ/outside.jsp?survey=cu. Accessed February 2012.

- 29.Naderi SH, Bestwick JP, Wald DS. Adherence to drugs that prevent cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis on 376,162 Patients. Am J Med. 2012 Jun 27.[Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 22748400. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Hayden M, Pignone M, Phillips C, Mulrow C. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events: a summary of the evidence for the US preventive services task force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(2):61–172. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-2-200201150-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Straube S, Tramèr MR, Moore RA, Derry S, McQuay HJ. Mortality with upper gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation: effects of time and NSAID use. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;9:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-9-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.www.Walgreens.com, accessed 9Sep11.

- 33.Ingenix, Inc. The Essential RBRVS (2012): A comprehensive listing of RBRVS values for CPT and HCPCS Codes. St. Anthony Publishing, 2012.

- 34.HCUPnet. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). 2009. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. http://www.ahrq.gov/HCUPnet/ Accessed 7Mar2012. [PubMed]

- 35.Friedman B, La Mare J, Andrews R, McKenzie DH. Assuming an average cost to charge ratio of 0.5: practical options for estimating cost of hospital inpatient stays. J Health Care Finance. 2002;29(1):1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Russell MW, Huse DM, Drowns S, Hamel EC, Hartz SC. Direct medical costs of coronary artery disease in the United States. Am J Cardiol. 1998;81(9):1110–5. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(98)00136-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics - 2011 Update: A report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2011;123(4):e18–e209. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182009701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leibson CL, Hu T, Brown RD, Hass SL, O’Fallon WM, Whisnant JP. Utilization of acute care services in the year before and after first stroke: A population-based study. Neurology. 1996;46(3):1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Menzin J, Wygant G, Hauch O, Jackel J, Friedman M. One-year costs of ischemic heart disease among patients with acute coronary syndromes: findings from a multi-employer claims database. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(2):461–468. doi: 10.1185/030079908X261096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Augustovski FA, Cantor SB, Thach CT, Spann SJ. Aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular events. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(12):824–35. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00246.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nease RF, Kneeland T, O’Connor GT, et al. Variation in patient utilities for outcomes of the management of chronic stable angina. JAMA. 1995;273(5):1185–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03520390045031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gore JM, Granger CB, Simoons ML, Sloan MA, Weaver WD, White HD, et al. Stroke after thrombolysis: mortaltiy and functional outcomes in the GUSTO-I trial. Circulation. 1995;92(10):2811–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.92.10.2811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsevat J, Goldman L, Soukup JR, et al. Stability of time-tradeoff utilities in survivors of myocardial infarction. Med Decis Making. 1993;13(2):161–5. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9301300210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 231 kb)